Abstract

Introduction and Aims

Methamphetamine use leads to increased likelihood of premature death. The authors investigated the causes of death and risk of mortality in a large cohort of patients with methamphetamine dependence.

Design and Methods

A cohort of 1,254 subjects with methamphetamine dependence, admitted to a psychiatric center in Taiwan from January 1990 to December 2007, was retrospectively studied. Diagnostic and sociodemographic data for each subject were extracted from the medical records based on a chart review process. Mortality data were obtained by linking to the National Death Certification System and standardised mortality ratios (SMRs) were estimated. The risk and protective factors for all-cause deaths were explored by means of survival analyses.

Results

During the study period, 130 patients died. Of them, 63.1% died unnatural deaths, while the remaining 36.9% died natural deaths. The 1-year cumulative rates for unnatural and natural deaths were 0.018 and 0.006, respectively and the 5-year rates were 0.046 and 0.023, respectively. The cohort had excessive mortality (SMR = 6.02), and women had a higher SMR for unnatural deaths than men (26.19 vs. 9.82, P = 0.001). For all-cause deaths, comorbiditywith other substance use disorders was associated with increased risk of death, despite that being married was associated with a reduced risk.

Discussion and Conclusions

A substantial proportion of the deceased died natural deaths, but most died unnatural deaths. The findings show significant evidence to provide valuable insight into premature deaths among methamphetamine-dependent users. This information is valuable for development of prevention and intervention programs.

Keywords: methamphetamine, cohort, mortality, natural death, unnatural death

INTRODUCTION

Methamphetamine dependence rose to epidemic levels after the 1990s, with increasingly widespread use in East Asia and the Pacific region [1], South Africa [2] and North America [3]. In recent years, emerging literature [4, 5] identified the physical harms of methamphetamine including overdose or toxicity, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular pathology, and blood-borne virus transmission, along with psychological harms such as psychosis, depression, and suicide. Of the harms, mortality is the most extreme, which can be precipitated under existing physical or psychological harms.

Several studies investigated methamphetamine-related deaths based on coroners’ verdicts [6–9]. This type of data is limited for investigating the distribution of cause of death. A death must be reported mandatorily to a coroner when a person died either in a sudden or violent manner. Therefore, these findings reveal that the majority of deaths were unnatural [6–9], especially accidental deaths; natural deaths were rare. The true distribution of natural and unnatural deaths remains unclear among patients with methamphetamine dependence, in part because of the large cohorts required for study.

A recent systematic review [10] highlighted eight cohort studies that investigated the mortality of amphetamine users, but they have several limitations. Of the eight cohorts included in the review, only three had a sample size of 500 or larger [11–13]. Additionally, only two studies reported on causes of death and existing inconsistent findings [12, 13]. In a Czech cohort, 41 of the 48 deaths were injury-related [12]. A Swedish cohort was dominated by heroin overdose deaths (15 of 39 deaths), followed by accidental deaths [13]. Therefore, additional studies with larger sample sizes are needed to replicate and clarify the findings.

In this study, we conducted a follow-up study in a cohort of at least 1200 inpatients with methamphetamine dependence. The aim of the study was to investigate the rates of all-cause, natural, and unnatural deaths and calculate the standardised mortality ratios (SMRs) for these three endpoints. Potential sociodemographic and clinical factors in association with the endpoints were explored.

METHODS

Study population

The background of Taipei City Psychiatric Center has been described in great detail elsewhere [14]. All of the inpatients with methamphetamine dependence who underwent detoxification from January 1, 1990 through December 31, 2007 were enrolled in this retrospective cohort study. The inclusion criterion was a principal psychiatric diagnosis of methamphetamine dependence according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition Revised (DSM-III-R) and Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) [15, 16]. We used the discharge diagnoses regularly made by a senior, in-charge, board-certificated psychiatrist who reviewed several types of clinical information on each inpatient during each admission, including a positive urine test for methamphetamine use shortly before hospitalisation. If a patient had multiple hospitalisations during the study period, the earliest one was defined as the index admission. To confirm the principal diagnosis and comorbidities of each subject, a chart review process was carefully conducted by two trained clinical psychologists, which was then double-checked by a senior psychiatrist (CJK). Furthermore, we excluded any patient whose principal psychiatric diagnosis after the index admission was changed to any other substance use disorder, such as heroin or alcohol. Consequently, 1254 subjects fulfilled with the study criteria and were enrolled.

Methamphetamine use in Taiwan

Methamphetamine is used predominantly in the crystal form in Taiwan [17]. In some cases methamphetamine is put on a piece of tinfoil, heated underneath, then inhaled as smoke, or, more commonly, an ‘inhaling ball’ ball is used. In this study, all of the subjects inhaled or smoked methamphetamine.

Data collection

Semi-structured case notes were used for any patient who was admitted to Taipei City Psychiatric Center after 1980; they are described in previous works [18, 19]. For facilitating data collection, a short review form was designed for the reviewing process that consisted of demographic information and psychiatric diagnoses at the index admission. Demographic information included age, gender, educational level, marital status, and lifetime and recent 1-year employment histories. Psychiatric comorbidities consisted of two categories: 1) other substance use disorder(s), including heroin, alcohol, glue, and other psychoactive substances, and 2) non-substance-related psychiatric disorders. The chart review process took about 20 to 25 minutes for each subject. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Committee on Human Subjects of Taipei City Hospital.

Mortality case ascertainment

By means of the unique national identification number, each cohort subject was electronically linked to and compared against the Department of Health Death Certification System in Taiwan from January 1, 1990 through December 31, 2007, and 130 deaths were identified. Deaths due to suicide (ICD-9 code E950-959), accident (E800-949, including accidental overdose), homicide (E960-978), and undetermined unnatural death (E980-989) were categorised as unnatural deaths. All remaining causes of death were considered natural. The linking process was conducted by a statistician, and the chart reviewers were blinded to the subjects’ mortality status.

Statistical analyses

To avoid immortal time bias [20], the survival time for each deceased was calculated from the index admission discharge until death. The survival time for each living subject was calculated from the index discharge to the end of the study. The cumulative mortality rates for unnatural and natural deaths are presented by means of life-table analyses. Relative to the general population, a standardised mortality ratio (SMR) was calculated by dividing the observed number of deaths by the expected number of deaths [21]. Gender difference in SMRs were analysed by Poisson regression analysis using Egret for Windows [22]; the P value of the relative SMR ratio, i.e., the SMR for women relative to that of men, was estimated. Multivariate Cox proportional-hazards analyses based on backward variable selection were conducted to estimate the hazard ratios for associations between potential variables and each outcome of interest (all-cause, natural, and unnatural deaths). Variables with at least a moderate association (P < 0.20) were included in the final multivariate model. The SAS software (version 9.1, SAS Institutes Inc., Cary, NC, USA) PROC Phreg was used for the analysis. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

RESULTS

Baseline information

Of 1254 subjects, 1009 were men (Table 1) and the mean (standard deviation) age at index admission was 28.4 (7.6) years, with a range of 15.2 to 87.8 years. Most of the subjects were single (64.3%), followed by married (17.9%). Most (88.6%) of the subjects had been employed in their lifetimes, while just over half of them (58.6%) were employed in the recent year before the index admission. At the index admission, significantly more women were less than 25 years of age and had more non-substance-related psychiatric disorders than did men. Significantly fewer women were employed in the recent year and were single (Table 1). No significant gender difference was found in the distribution of methamphetamine-induced psychoses.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical status at the index admission among the patients with methamphetamine dependence (n=1,254)

| Characteristics | Men (N=1,009) |

Women (N=245) |

statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Age | X2=39.06 | ||||

| <25 | 290 | 28.7 | 121 | 49.4 | df=2 |

| 25–44 | 693 | 68.7 | 117 | 47.8 | p<0.001 |

| ≥45 | 26 | 2.6 | 7 | 2.9 | |

| Education level | X2=0.95 | ||||

| College and above | 64 | 6.3 | 12 | 4.9 | df=2 |

| Senior high | 491 | 48.7 | 117 | 47.8 | p=0.621 |

| Junior high and below | 454 | 45.0 | 116 | 47.3 | |

| Marriage | X2=25.67 | ||||

| Single | 669 | 66.3 | 137 | 55.9 | df=2 |

| Married | 187 | 18.5 | 37 | 15.1 | p<0.001 |

| Others | 153 | 15.2 | 71 | 29.0 | |

| Lifetime employmenta | X2=2.07 | ||||

| No | 103 | 10.7 | 33 | 14.0 | df=1 |

| Yes | 858 | 89.3 | 202 | 86.0 | p=0.150 |

| Recent 1-year employmentb | X2=5.43 | ||||

| No | 383 | 38.7 | 114 | 46.9 | df=1 |

| Yes | 606 | 61.3 | 129 | 53.1 | p=0.020 |

| Methamphetamine-induced psychosis | X2=0.24 | ||||

| No | 342 | 33.9 | 79 | 32.2 | df = 1 |

| Yes | 667 | 66.1 | 166 | 67.8 | P =0.62 |

| Comorbidity | X2=6.68 | ||||

| No | 421 | 41.7 | 83 | 33.9 | df=2 |

| Other substance use disorder(s) | 297 | 29.4 | 73 | 29.8 | p=0.036 |

| Non-substance-related psychiatric disorder(s) | 291 | 28.8 | 89 | 36.3 | |

missing value=58,

missing value=22

Causes of death

During the study period, 130 patients died. Of them, 63.1% (82/130) died unnatural deaths, while the remaining 36.9% (48/130) of subjects died natural deaths. The total observation time was 10,032.8 person-years. The most common causes of unnatural deaths were suicide (n = 42, 32.3% of total mortality), accidents (n = 26, 20.0%), and undetermined unnatural deaths (n = 14, 10.8 %) but no homicide (n = 0). There were four subjects who died from accidental overdoses (ICD-9 code E851-855). Among those who died natural deaths, the most common causes were cardiovascular disease (code 390-429, n = 13), undetermined natural deaths (n = 9), and hepatic diseases (code 570-573, n = 6). Other categories of causes had fewer than five cases. No one died from HIV-related disease (code 042-044).

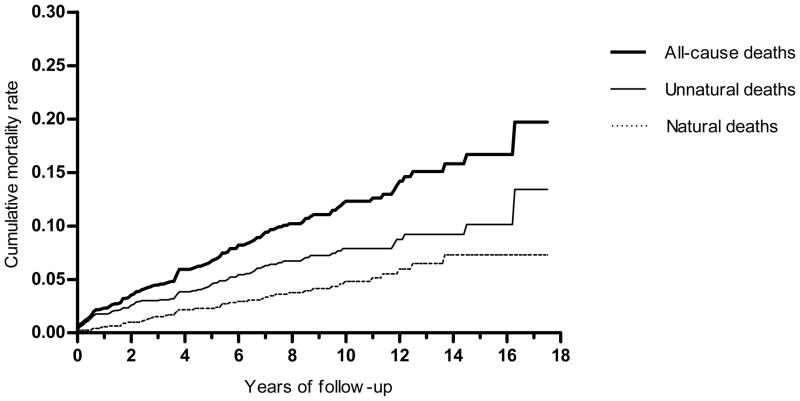

We found higher short-term rates for unnatural deaths than for natural deaths (Figure 1). The 1-year cumulative rate for unnatural death was 0.018, which was higher than that for natural deaths (0.006); the rate ratio of unnatural death to natural death was 3.0. Of 28 subjects who died within 1 year, 22 died unnatural deaths (7 suicides, 9 accidents, and 6 undetermined unnatural causes) and 6 died natural deaths (3 due to undetermined natural causes and 1 each due to cardiovascular, genitourinary, and cancer causes).

Figure 1.

The life table reveals the cumulative mortality rates for the endpoints of all deaths, natural deaths, and unnatural deaths among inpatients with methamphetamine dependence, 1990–2007 (n = 1,254).

For the long-term period after the index admission discharge, more subjects died of natural causes than unnatural causes. The 5-year cumulative rates for unnatural and natural deaths were 0.046 and 0.023, respectively; the rate ratio was 2.0. Of the 77 subjects who died within 5 years of their index admission, 51 died unnatural death (25 suicides, 16 accidents, and 10 undetermined unnatural causes); the remaining 26 subjects died natural deaths (2 due to cancer, 3 due to diabetes mellitus, 8 due to cardiovascular events, 4 due to respiratorydisease, 4 due to gastrointestinal causes, 1 due to a genitourinarycause, and 4 due to undetermined natural causes). The 17-year cumulative survival rate was 0.80, which indicates that one-fifth of the total subjects died during the study period.

As for methamphetamine-induced psychosis, 89 subjects with psychosis died, while 41 without psychosis died. Of those who died without psychosis, the proportion of natural deaths was 43.9% (18/41), while the corresponding proportion for those with psychosis who died natural deaths was 30.3% (27/89) (X2 = 2.28, df = 1, p = 0.131). That the difference did not reach statistical significance could be due to the small sample size studied.

Standardised mortality ratios

Relative to the general population, the study subjects had an excessive mortality rate (SMR = 6.02). The SMR for unnatural death tended to be higher than that for natural death. There were no significant differences in the SMRs for all-cause mortalityand natural death between men and women (Table 2). However, the SMR for unnatural death among women was significantly higher than among men (26.19 vs. 9.82, P = 0.001).

Table 2.

Standardised mortality ratios among the psychiatric inpatients with methamphetamine dependence who were admitted between 1990 and 2007, with the record linkage for obtaining the status of mortality at the same study period (N = 1,254).

| Gender | All-cause deaths | Natural deaths | Unnatural deaths | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oa | Eb | SMR (SE)c | Oa | Eb | SMR (SE)c | Oa | Eb | SMR (SE)c | |

| Men | 113 | 19.64 | 5.75 (0.54) | 44 | 12.61 | 3.49 (0.53) | 69 | 7.03 | 9.82 (1.18) |

| Women | 17 | 1.96 | 8.69 (2.11) | 4 | 1.46 | 2.74 (1.37) | 13 | 0.50 | 26.19 (7.26)** |

| Total | 130 | 21.59 | 6.02 (0.53) | 48 | 14.07 | 3.41 (0.49) | 82 | 7.52 | 10.90 (1.20) |

observed number of deaths;

expected number of deaths;

Standard error.

All SMRs are significantly different from 1.

p=0.001 for gender difference based on the Poisson regression in unnatural deaths; p=0.643 in natural deaths; p=0.113 in all-cause deaths.

The SMRs in categories of causes of death were further estimated if the number of cases was greater than five. As for the specified category of unnatural death, the SMRs (standard error) for suicide and accidental death were 17.1 (2.6) and 5.4 (1.1), respectively. As for natural death, the SMRs for cardiovascular and hepatic diseases were 14.7 (4.2) and 6.0 (2.3), respectively.

Risk and protective factors for death

The presence of psychosis was not associated with the risks of all-cause death (hazard ratio = 1.086, P = 0.66), natural death (hazard ratio = 0.847, P = 0.58), or unnatural death (hazard ratio = 1.273, P = 0.33). Thus, psychosis was not entered into the multivariate analysis. Gender and employment (either lifetime or 1-year) were not associated with risk of death either. Multivariate Cox regressions were used to assess the simultaneous impact of several potential variables (Table 1) on all-cause, natural, and unnatural deaths, separately. In terms of all-cause death, being married was associated with a reduced risk of death, despite comorbidity with other substance use disorders, which was associated with substantially increased risk of all-cause death. Furthermore, the risk factors for natural death include the age older than 45 and comorbidity with other substance disorders. A protective factor for unnatural death was being married.

DISCUSSION

The strength of this study is that a large cohort of patients with methamphetamine dependence was investigated for the causes of death; such knowledge is advantageous for the development of prevention, intervention, and rehabilitation policies benefiting individuals using methamphetamine. We used strict psychiatric diagnostic criteria to confirm that each study subject was diagnosed with methamphetamine dependence to estimate the SMRs of all-cause and specific causes of death, which has rarely been investigated.

In Taiwan, coroners must be medical doctors or hold masters or doctorates of forensic medicine. The coroners have a statutory responsibility to investigate all cases in which death was unexpected, violent, or resulted from accident or injury. Their main concerns are to rule out the possibility of homicide, along with differentiating other unnatural deaths from natural deaths. Therefore, the misclassifications of unnatural and natural deaths is likely minimal.

Natural deaths

This study demonstrated a longitudinal pattern of natural death, which is not previously described in the literature for chronic use of methamphetamine. The study revealed that natural deaths steadily accumulated for every year during the follow-up period. Moreover, relative to the general population, methamphetamine-dependent patients had excessive natural deaths, at 3.4 times the SMR. Thus, methamphetamine does persistent harm to physiological systems and contributes to the increased number of natural deaths.

The literature shows that approximately half of fatal methamphetamine toxicity cases confirmed by coroners involved concomitant use of other substances, most commonly alcohol (10%–25%), cocaine (12%–25%), and morphine (20%–30%) [8, 23]. We found that comorbidity with other substance use disorders was a risk factor for natural deaths in this study. Consistent with previous studies [24, 25], one possible explanation is that the concomitant use of other substances with methamphetamine increased methamphetamine toxicity synergistically.

Methamphetamine is reportedly more cardiotoxic than opioids [4, 26]. In our study, cardiovascular disease was the leading cause of natural deaths (10.0% of the total mortality). Nonetheless, a previous study [14] revealed that cardiovascular deaths among heroin users who were admitted to the same source hospital contributed to 15% of total mortality, which is similar to the proportion of methamphetamine dependent subjects. One possible explanation is that other causes of death, including unnatural deaths, could be strongly competing risks for mortality. Asubstantial portion of the subjects could have died of other causes instead of cardiovascular diseases. The finding that no subject died of HIV-related disorders during the observation period could be attributed to the use of inhalation as the route of administration by methamphetamine users in Taiwan.

Unnatural deaths

This study showed that the rate ratio of unnatural deaths to natural deaths peaked during the first year after the index admission. Thus, it is important to find ways to prevent premature unnatural deaths in the short-term after discharge from the index hospital admission. The survival analysis showed that being married lowered the risk for unnatural death. Nonetheless, being married was not significantly associated with suicide, which contributed 51.2% (42/82) to unnatural deaths (hazard ratio = 0.45, P = 0.134, with reference to the single group), possibly due to the small sample size. Past studies reported married people were more likely to engage in positive, and less in negative, health behaviors than single people [27, 28]. We believe marriage in this specific group provided social networks and/or social support [29], which kept the subjects from the risks of unnatural death. Long-term methamphetamine use is associated with higher levels of psychosis, depression, and suicide [4, 30–32]. Most (66.4%, 833/1254) of the subjects in this study had methamphetamine-induced psychoses at the index admission, which reflected chronicity of methamphetamine use. Based on this, a higher risk of subsequent suicide was expected. Thus, suicide was the strongest competing cause of death in the study, which contributed to nearly one-third of the total mortality and the high SMR of 17.1. Research to investigate the risk and protective factors for suicide among methamphetamine dependent subjects are needed for the development of suicide prevention programs.

Methamphetamine users with co-occurring psychosis may benefit from early psychosocial and/or pharmacological interventions to address psychiatric symptoms [33]. In our study, there was no association between psychosis and mortality. Thus, the protective effect of earlier interventions could have compensated for subjects with severe methamphetamine-related psychosis, which indicates long-term methamphetamine use [34].

Research demonstrated that unemployment is linked with increased mortality in the general population, possibly through mediators such as poor psychological well-being (e.g., depression) and unhealthy behaviors (e.g., substance abuse) [35, 36]. However, we found no association between employment and mortality among methamphetamine-dependent patients. Future studies should clarify this issue.

Gender differences for Standardised Mortality Ratios

The evidence-based information regarding SMR among methamphetamine dependent individuals is rare and only one study reported SMRs for stimulant users [12]. We estimated all-cause SMRs of 6.02 overall, 8.69 for women, and 5.75 for men. The magnitudes of these SMRs were similar to the findings of the Czech study[12], with the overall SMRs of 6.22, 7.84 for women, and 5.87 for men.

Despite no significant difference in SMR for all-cause death or natural death, women had a significantly higher SMR for unnatural death than men in this study. This implies an important issue that methamphetamine dependent women have excess unnatural deaths, and the health gap between patients with methamphetamine dependence and the general community is wider for women than for men. However, women were not significantlyassociated with unnatural deaths in the multivariate Cox regression analysis (Table 3), for which methamphetamine dependent men served as the referent group instead of women in the general community. Thus, the present case for gender difference should be neglected if SMRs cannot be estimate. We found inadequate data on women to discuss potential gender differences regarding the association of methamphetamine use and unnatural death. Future work will be needed to explore factors related to gender differences for prioritising prevention and intervention efforts accordingly.

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox proportional-hazards regression of association between the potential factors and all-cause, natural, and unnatural deaths separately(N = 1,254)

| Characteristics | All-cause deaths |

Natural deaths |

Unnatural deaths |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | p | N | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | p | n | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | p | |

| Sex | 0.163 a | 0.117 a | ||||||||||

| Women | 17 | Reference | - | 4 | Reference | - | 13 | - | - | |||

| Men | 113 | 1.45 | 0.86–2.46 | 0.163 | 44 | 2.29 | 0.81–6.43 | 0.117 | 69 | - | - | |

| Age at index admission | 0.178 a | 0.041 a | ||||||||||

| <25 | 39 | Reference | - | 9 | Reference | - | 30 | - | - | |||

| 25–44 | 86 | 1.21 | 0.80–1.82 | 0.366 | 36 | 1.93 | 0.91–4.08 | 0.086 | 50 | - | - | |

| ≥ 45 | 5 | 2.48 | 0.94–6.58 | 0.067 | 3 | 5.19* | 1.38–19.57 | 0.015 | 2 | - | - | |

| Education level | 0.082 a | 0.096 a | ||||||||||

| College and above | 7 | Reference | - | 2 | Reference | - | 5 | - | - | |||

| Senior high | 48 | 0.76 | 0.34–1.69 | 0.501 | 15 | 0.97 | 0.22–4.27 | 0.971 | 33 | - | - | |

| Junior high and below | 75 | 1.16 | 0.53–2.55 | 0.712 | 31 | 1.90 | 0.45–8.03 | 0.383 | 44 | - | - | |

| Marriage | 0.104 a | 0.025 a | ||||||||||

| Single | 91 | Reference | - | 28 | - | - | 63 | Reference | - | |||

| Married | 17 | 0.55* | 0.32–0.96 | 0.034 | 10 | - | - | 7 | 0.32** | 0.14–0.74 | 0.008 | |

| Others | 22 | 0.93 | 0.57–1.52 | 0.769 | 10 | - | - | 12 | 0.77 | 0.41–1.43 | 0.402 | |

| Comorbidity at index admission | 0.005 a | 0.028 a | 0.076 a | |||||||||

| No | 48 | Reference | - | 14 | Reference | - | 34 | Reference | - | |||

| Other substance use disorder(s) | 53 | 1.64* | 1.09–2.45 | 0.017 | 23 | 2.33* | 1.18–4.61 | 0.015 | 30 | 1.35 | 0.82–2.24 | 0.239 |

| Non-substance psychiatric disorder(s) | 29 | 0.80 | 0.50–1.27 | 0.339 | 11 | 1.14 | 0.51–2.53 | 0.746 | 18 | 0.67 | 0.37–1.21 | 0.184 |

testing for the significance of the variable; other p values in the table: testing for the significance of the specified category

Limitations

The present study is limited in several ways. First, the cohort consisted of clinical patients who were recommended for hospitalisation due to prominent methamphetamine-related problems, such as social functional impairment, behavioral disturbances, and psychoses. Thus, our findings might not be generalisable to methamphetamine users in the communityat large. Second, the data subsequent to the index admission were limited, in particular the use of methamphetamine (continuous/abstinence) and the potential confounders that included other substances (such as opioids and alcohol) and comorbid psychiatric disorders (such as depression). Thus, the relationship between methamphetamine use and death is limited to be concluded, because death could be independent of methamphetamine use, or be due to other factors that are incidentally associated with methamphetamine use, such as risk-taking behavior or tobacco use. Third, in this study, only demographic and diagnosis-related variables were collated, and some important predictors for natural and unnatural deaths were not examined. Further insight might be gained via nested case-control studies, which obtain more candidate variables, such as psychopathological profiles and laboratory data.

Implications

In summary, we found that patients with methamphetamine dependence had a 6-fold risk of mortalitywhen compared to the general population. In the short-term post-discharge period, it is important to find ways to prevent unnatural deaths. In the long-term, a substantial proportion of the deceased died natural deaths, which also warrants clinical attention. Women had a higher SMR for unnatural death than men, which implies that the health gap between methamphetamine-dependent patients and the general population in women is potentially larger than that for men.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by grants from the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC 97-2314-B-532-002-MY2), Taipei City Hospital, Taiwan (97001-62-001), and the National Institutes of Health (P20 MH071897), Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

The authors thank Yeates Conwell, MD and Kenneth Conner, PsyD, MPH for providing advice on study design and Xiao-Wei Sung and Chien-Wei Lin for data collection.

Footnotes

Drs. C.J. Kuo and C.C. Chen contributed equally to this article.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Farrell M, Marsden J, Ali R, Ling W. Methamphetamine: drug use and psychoses becomes a major public health issue in the Asia Pacific region. Addiction. 2002;97:771–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parry CD, Myers B, Pluddemann A. Drug policy for methamphetamine use urgently needed. S Afr Med J. 2004;94:964–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maxwell JC, Rutkowski BA. The prevalence of methamphetamine and amphetamine abuse in North America: a review of the indicators, 1992–2007. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27:229–35. doi: 10.1080/09595230801919460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darke S, Kaye S, McKetin R, Duflou J. Major physical and psychological harms of methamphetamine use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27:253–62. doi: 10.1080/09595230801923702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaye S, McKetin R, Duflou J, Darke S. Methamphetamine and cardiovascular pathology: a review of the evidence. Addiction. 2007;102:1204–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Degenhardt L, Roxburgh A, Barker B. Underlying causes of cocaine, amphetamine and opioid related deaths in Australia. J Clin Forensic Med. 2005;12:187–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jcfm.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu BL, Oritani S, Shimotouge K, Ishida K, Quan L, Fujita MQ, et al. Methamphetamine-related fatalities in forensic autopsy during 5 years in the southern half of Osaka city and surrounding areas. Forensic Sci Int. 2000;113:443–7. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(00)00281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karch SB, Stephens BG, Ho CH. Methamphetamine-related deaths in San Francisco: demographic, pathologic, and toxicologic profiles. J Forensic Sci. 1999;44:359–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaye S, Darke S, Duflou J, McKetin R. Methamphetamine-related fatalities in Australia: demographics, circumstances, toxicology and major organ pathology. Addiction. 2008;103:1353–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singleton J, Degenhardt L, Hall W, Zabransky T. Mortality among amphetamine users: a systematic review of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartu A, Freeman NC, Gawthorne GS, Codde JP, Holman CD. Mortality in a cohort of opiate and amphetamine users in Perth, Western Australia. Addiction. 2004;99:53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lejckova P, Mravcik V. Mortality of hospitalized drug users in the Czech Republic. Journal of Drug Issues. 2007;37:103–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fugelstad A, Annell A, Rajs J, Agren G. Mortality and causes and manner of death among drug addicts in Stockholm during the period 1981–1992. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;96:169–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb10147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen CC, Kuo CJ, Tsai SY. Causes of death of patients with substance dependence: a record-linkage study in a psychiatric hospital in Taiwan. Addiction. 2001;96:729–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9657298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin SK, Ball D, Hsiao CC, Chiang YL, Ree SC, Chen CK. Psychiatric comorbidity and gender differences of persons incarcerated for methamphetamine abuse in Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58:206–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2003.01218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo CJ, Tsai SY, Lo CH, Wang YP, Chen CC. Risk factors for completed suicide in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:579–85. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuo CJ, Tsai SY, Liao YT, Conwell Y, Lin SK, Chang CL, et al. Risk and protective factors for suicide among patients with methamphetamine dependence: a nested case-control study. J Clin Psychiatry. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05360gry. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suissa S. Immortal time bias in pharmaco-epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:492–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breslow NE, Day NE. The design and analysis of cohort studies. II. Lyon: International agency for research on cancer; 1987. Statistical methods in cancer research. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cytel Software Corp. Egret for windows [computer program]. Version 2.0.31. Cambridge; Mass: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Logan BK, Fligner CL, Haddix T. Cause and manner of death in fatalities involving methamphetamine. J Forensic Sci. 1998;43:28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albertson TE, Derlet RW, Van Hoozen BE. Methamphetamine and the expanding complications of amphetamines. West J Med. 1999;170:214–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendelson J, Jones RT, Upton R, Jacob P., 3rd Methamphetamine and ethanol interactions in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995;57:559–68. doi: 10.1016/0009-9236(95)90041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darke S, Degenhardt L, Mattick R. Epidemiology, causes and intervention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. Mortality amongst illicit drug users. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joung IM, Stronks K, van de Mheen H, Mackenbach JP. Health behaviours explain part of the differences in self reported health associated with partner/marital status in The Netherlands. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49:482–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.5.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wyke S, Ford G. Competing explanations for associations between marital status and health. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34:523–32. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eng PM, Rimm EB, Fitzmaurice G, Kawachi I. Social ties and change in social ties in relation to subsequent total and cause-specific mortality and coronary heart disease incidence in men. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:700–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.8.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zweben JE, Cohen JB, Christian D, Galloway GP, Salinardi M, Parent D, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in methamphetamine users. Am J Addict. 2004;13:181–90. doi: 10.1080/10550490490436055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKetin R, McLaren J, Lubman DI, Hides L. The prevalence of psychotic symptoms among methamphetamine users. Addiction. 2006;101:1473–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall W, Hando J, Darke S, Ross J. Psychological morbidity and route of administration among amphetamine users in Sydney, Australia. Addiction. 1996;91:81–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.9118110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glasner-Edwards S, Mooney LJ, Marinelli-Casey P, Hillhouse M, Ang A, Rawson R. Clinical course and outcomes of methamphetamine-dependent adults with psychosis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:445–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen CK, Lin SK, Sham PC, Ball D, Loh EW, Hsiao CC, et al. Pre-morbid characteristics and co-morbidity of methamphetamine users with and without psychosis. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1407–14. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davila EP, Christ SL, Caban-Martinez AJ, Lee DJ, Arheart KL, LeBlanc WG, et al. Young adults, mortality, and employment. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52:501–4. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181d5e371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lundin A, Lundberg I, Hallsten L, Ottosson J, Hemmingsson T. Unemployment and mortality--a longitudinal prospective study on selection and causation in 49321 Swedish middle-aged men. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:22–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.079269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]