Abstract

We investigated the effect of pH on the competition of two closely related chrysomonad species, Poterioochromonas malhamensis originating from circumneutral Lake Constance, and Ochromonas sp. isolated from a highly acidic mining lake in Austria (pH ∼2.6). We performed pairwise growth experiments between these two species at four different pH ranging from 2.5 to 7.0. Heterotrophic bacteria served as food for both flagellates. Results were compared to growth rates measured earlier in single species experiments over the same pH range. We tested the hypothesis that the acidotolerant species benefits from competitive release under conditions of acid stress. The neutrophilic strain numerically dominated over the acidotolerant strain at pH 7.0, but was the inferior competitor at pH 2.5. At pH 3.5 and 5.0 both strains coexisted. Surprisingly, P. malhamensis prevailed over Ochromonas sp. under moderately acidic conditions, i.e. at the pH where growth rates of the latter peaked when grown alone. Since bacterial food was not limiting, resource competition is improbable. It appears more likely that P. malhamensis ingested cells of its slightly smaller competitor. Adverse effects mediated via allelopathy, either directly on the competing flagellate or indirectly by affecting its bacterial food, might also have affected the outcome of competition.

Keywords: Competition, pH, Ochromonas, Poterioochromonas malhamensis, Acid mining lake

Introduction

The chrysophyte genera Ochromonas and Poterioochromonas are commonly found in a broad range of aquatic habitats (Boëchat et al. 2007; Boenigk et al. 2005). A likely reason for their ecological success is that species within both genera can have different nutritional modes. Mixotrophy, the combination of autotrophic growth via photosynthesis with the uptake of dissolved organic matter or bacteria, is widespread in these chrysomonads (Aaronson and Baker 1959; Bennett et al. 1990; Sanders et al. 1990). Another reason for their ecological success is their ability to produce toxins that may adversely affect potential predators such as cladocerans and rotifers (Boenigk and Stadler 2004). Recently, Blom and Pernthaler (2010) reported antibiotic effects of Ochromonas danica and the same Poterioochromonas strain as used in the present investigation on freshwater bacteria. The antibiotic effects were not only strain-specific, but depended also on the nutritional mode of the flagellates.

Chrysophytes reach the highest relative abundances in oligotrophic lakes where resources are limiting (Sandgren 1988). Generally, mixotrophy is a successful life style that enables the organisms to overcome unfavourable conditions and to colonize harsh environments (Jones 1994). In accordance with this view, several species of the genus Ochromonas belong to the most important pioneer colonists in oligotrophic, man-made acid mining lakes (Nixdorf et al. 1998). Acidic mining lakes (AML) are extreme aquatic habitats (pH often < 3) with strongly reduced biodiversity (Gaedke and Kamjunke 2006; Geller et al. 1998) and are found on all continents. The organisms thriving in these lakes may be highly specialized new colonizers (acidophilic species), or they may be generalists (acidotolerant species) taking refuge from otherwise superior competitors or predators that are less tolerant of the harsh environmental conditions (Tittel et al. 2003; Wollmann et al. 2000).

The definitions of acidophilic, acidotolerant and neutrophilic are somewhat ambiguous across different taxa (Moser and Weisse 2011a). We define an acidophilic species as a species that shows a clear fitness optimum under highly acidic conditions. An acidotolerant species is able to grow both at circumneutral and acidic pH, but thrives at moderately acidic conditions. A neutrophilic species has its fitness optimum at circumneutral conditions.

Due to the low pH, supply of CO2 is limited in AML because of the absence of the bicarbonate pool (Gross 2000). As a consequence, the relative contribution of mixotrophic flagellates to the algal community is higher in AML than in circumneutral water bodies (Gaedke and Kamjunke 2006). Ochromonas spp. are the most important bacterial grazers, removing up to 88% of the daily bacterial production in the epilimnion of AML (Schmidtke et al. 2006). Experimental evidence demonstrated that the mixotrophs may even outcompete bacterivorous specialists (Tittel et al. 2003).

The goal of this study was to test the competitiveness of an acidotolerant chrysomonad isolated from an AML vs. a closely related, neutrophilic species under varying experimental pH. We assumed that the species dwelling in the AML would be the superior competitor at low pH, while the neutrophilic species would outcompete the specialist at circumneutral pH. We assessed population growth rates that can be used as a proxy for fitness in asexually reproducing protists (Weisse 2006). Our hypothesis was that the acidotolerant species would benefit from competitive release under conditions of acidic stress. An as yet unidentified Ochromonas sp. strain isolated from a highly acidic (pH ∼2.6) mining lake in Austria represented the acidotolerant species. Poterioochromonas malhamensis strain DS that had been isolated from weakly alkaline Lake Constance (Stabel 1998) served as a model for a neutrophilic species. Most of the chrysomonad flagellates tested thus far for their pH tolerance were tolerant to widely changing pH ranging from 3 to 11 (Boenigk 2008). Previous experiments in our laboratory revealed that P. malhamensis is able to survive under acidic conditions, and that Ochromonas sp. can tolerate circumneutral pH for several generations (Moser and Weisse 2011a). In pursuit of the above hypothesis, we performed pairwise competition experiments with these two species over a pH range from 2.5 to 7.0.

Material and Methods

Study sites and organisms

The mixotrophic flagellates used in this study originated from an acid mining lake in Langau (Lower Austria, 48°50′N, 15°43′E) and from Lake Constance (47°35′N, 9°28′E). Isolation of a species of the genus Ochromonas Vysotskii, 1887 from the acid mining lake was achieved via dilution of lake water and individually pipetting of several cells. The species identity of Ochromonas sp. was verified by sequencing of the 18S rDNA and consecutive BLAST search (GenBank accession number FN429125). Accordingly, this flagellate belongs to the genus Ochromonas within the C3 cluster of the Spumella-like flagellates identified by Boenigk et al. (2005).

Several strains of Poterioochromonas malhamensis (Pringsheim 1952) Péterfi, 1969 (basionym Ochromonas malhamensis) have been used previously to investigate their growth and grazing rates (Zhang and Watanabe 2001), phototrophy vs. phagotrophy (Sanders et al. 1990), and antibiotic effects and toxicity (Blom and Pernthaler 2010; Boenigk and Stadler 2004). The P. malhamensis strain DS from Lake Constance used in the latter two cited studies and in the present investigation was isolated by Doris Springmann in the late 1980s. Since then it has been kept in batch cultures on a bacterial diet in our laboratory. The taxonomic identity of this strain was confirmed previously by molecular taxonomy. A full sequence of the SSU rDNA gene is available in GenBank (accession number AM981258.1). Sequence similarity of the 18S rDNA gene is 94% between the two flagellate strains used in this study. The cell size of P. malhamensis (5.52 ± 0.93 μm) was significantly larger (P < 0.001) than that of Ochromonas sp. (4.01 ± 0.58 μm) in our experimental treatments.

Flagellate stock cultures were maintained in modified Woods Hole Medium (MWC) as nonclonal, nonaxenic batch cultures at a continuous light intensity of 90–100 μmol m−2 s−1 and 17.5 °C. In the flagellate stock cultures originating from the acid mining lake, pH ranged from 2.6 to 3.0 because the natural pH of the acid mining lake is in the range of 2.3–3.7. The pH varied seasonally, but was mostly close to 2.6 (Moser and Weisse 2011b). Due to the oxidation of pyrite and marcasite this lake has been acidified from its beginning. As a consequence of this oxidation, this lake exhibits high iron (110–430 mg l−1) and sulphate (1100–1600 mg l−1) concentrations and, therefore, a high conductivity (Moser and Weisse 2011b). Poterioochromonas malhamensis was kept at pH 7.0 because Lake Constance is a neutral to weakly alkaline lake (Stabel 1998). All flagellate stock cultures were supplied with a wheat grain to stimulate growth of their bacterial food.

Experimental design

Experiments were conducted in 50-ml culture tissue flasks at moderate continuous light intensity (100 μmol m−2 s−1) provided from above by an Osram L 8W/954 Lumilux de Luxe Daylight lamp. Light intensity was measured with a spherical light sensor (Li-Cor 193, Li-Cor, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA). For technical reasons, we could not measure light intensity in the experimental containers. It is obvious that light intensity was somewhat reduced with increasing cellular abundance in the course of the experiments. If we assume that light intensity ranged from 90 to 100 μmol m−2 s−1 in the experimental containers, this intensity corresponds to the light level that is common in the upper 5 m of the AML at Langau (Moser and Weisse 2011b). The experimental volume in each flask was 40 ml. We performed pairwise competition experiments between the two flagellates at four different pH (2.5, 3.5, 5.0, and 7.0) and at a temperature of 17.5 °C. Prior to the beginning of the experiments, the two flagellate strains were stepwise acclimated to the different pH at the experimental temperature. The pH was adjusted by adding small amounts of 0.1 mol l−1 or 1 mol l−1 NaOH or HCl, respectively. It was increased or decreased by 0.5 pH units per day, until the culture reached the final pH. The experimental cultures had been acclimated to their final pH levels for at least 3–4 days. To minimize the risk of an initial lag-phase, flagellate cultures were diluted with MWC medium to reach the experimental abundances 3–4 h prior to the beginning of the experiments. All flagellate cultures were supplied with a wheat grain to stimulate bacterial growth thus providing saturating food levels.

The competition experiments were designed to yield initial abundances of ∼50,000 cells ml−1 of each of the two flagellate strains. Each experiment was run in triplicate and lasted for seven to eight days. The pH was measured at the beginning of the experiments and thereafter twice a day. If the pH differed by more than 0.2 units from the target value, it was adjusted by the addition of small amounts of 0.1 mol l−1 or 1 mol l−1 NaOH or HCl, respectively. All pH measurements were conducted with a pH meter (Mettler Toledo, Seven Easy pH Meter S20) to the nearest 0.01 unit. The pH sensor was three-point calibrated with standard buffer solutions of pH = 4.01, pH = 7.00, and pH = 9.21 prior to each measurement.

Every 24 h, 4-ml subsamples from each experimental container were fixed with formalin (2%, vol/vol final concentration) for measurements of flagellate and bacterial abundances. Each time before pH measurement and subsampling, the culture flasks were shaken to prevent wall growth of the flagellates and cell clumping. Cell numbers of the two flagellates and bacteria were measured with a flow cytometer (FacsCalibur, Becton Dickinson), using the software programmes “Cellquest” and “Attractors” (Becton Dickinson). In the competition experiments, the two flagellate strains differed according to their red vs. orange fluorescence signals and formed non-overlapping regions (‘gates’) in the corresponding 2D dot plots. Bacterial abundance was measured by means of their green fluorescence after staining with Syto 13 (Gasol and del Giorgio 2000).

Linear regression of ln cell numbers vs. time was used to assess the growth rates of the flagellates (μ, d−1) over the period of exponential growth; μ was obtained as the slope (=regression coefficient) of the respective regression. Correlation coefficients of all linear regressions reported were significant (P < 0.05). Growth rates obtained in the competition experiments were pairwise compared (Student's t-test) to growth rates measured earlier in single species experiments at the respective pH (Moser and Weisse 2011a). All statistical analyses were performed with Sigma Plot 11.0 and Sigma Stat 2.03 (SPSS Inc.).

Results

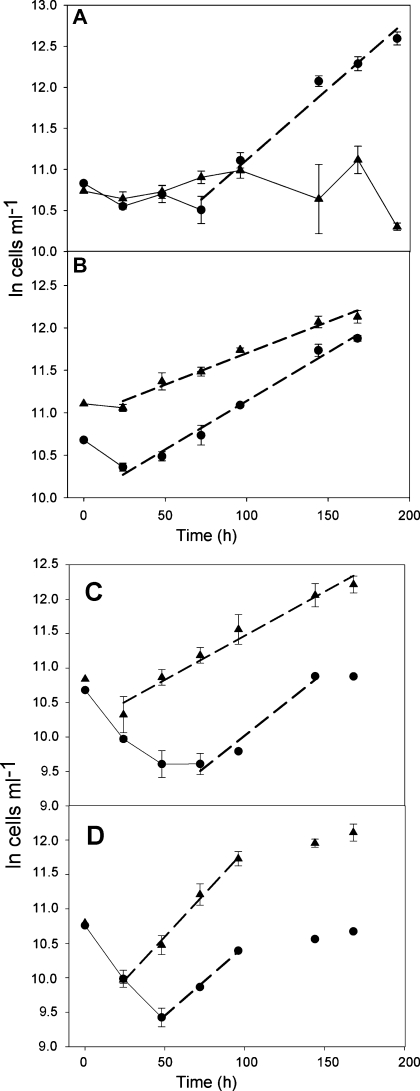

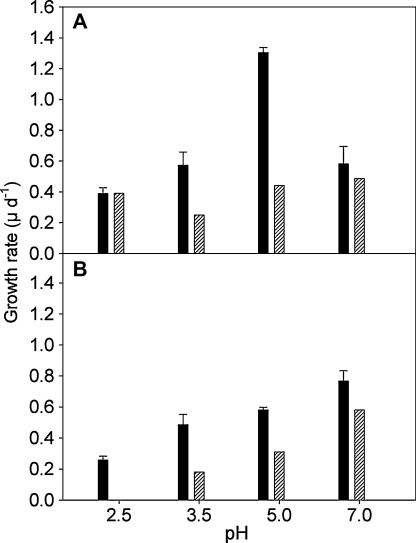

Irrespective of pH, cell numbers of both flagellate species decreased during the first 24 h of the experiments. In the experiment conducted at pH 2.5, cell numbers of both strains were similar and relatively constant during the initial 4 days (Fig. 1A), ranging from 40,000 to 65,000 cells ml−1. Beginning on day 4 of the experiment, the abundance of Ochromonas sp. increased exponentially until the end of the experiment. The slope of the regression line corresponded to an average μ of 0.39 d−1 during days 3–8, i.e. growth of Ochromonas sp. in the competition experiment was not statistically different from when grown alone at pH 2.5 (Fig. 2A). The final abundance of Ochromonas sp. was close to 300,000 cells ml−1, while the final abundance of P. malhamensis was lower than at the beginning of the experiment.

Fig. 1.

LN-transformed cell numbers of Ochromonas sp. (circles) and Poterioochromonas malhamensis (triangles) in the course of the competition experiments at pH 2.5 (A), pH 3.5 (B), pH 5.0 (C), and pH 7.0 (D). Symbols represent mean values of triplicates; the error bars denote 1 SD. A linear regression (dashed line) was calculated over the exponential growth of each strain.

Fig. 2.

Growth rates of Ochromonas sp. (A) and Poterioochromonas malhamensis (B) in the competition experiments reported in this study (hatched bars) compared to their growth rates obtained by Moser and Weisse (2011a) in single species experiments (black bars). The bars indicate mean values of triplicates; the error bars denote 1 SD.

At pH 3.5, cell numbers of both flagellate strains developed similarly. An initial lag-phase was followed by an exponential phase that lasted for the following six days (Fig. 1B). Growth rates calculated from the regression equations were 0.25 d−1 for Ochromonas sp. and 0.18 d−1 for P. malhamensis, i.e. growth rates of both species were significantly reduced (P = 0.003 and P = 0.001, respectively) relative to the single species experiments at the same pH (Fig. 2).

The experiments conducted at pH 5.0 and 7.0 yielded qualitatively similar results. After an initial reduction of both flagellate populations, cell numbers of P. malhamensis increased exponentially. At pH 5.0, the exponential phase lasted until the end of the experiment (Fig. 1C). At pH 7.0, the exponential growth phase of P. malhamensis was restricted to the period after day 1 and before day 5 of the experiment (Fig. 1D). Growth rates derived from the regression lines were 0.31 d−1 at pH 5.0 and 0.58 d−1 at pH 7.0, i.e. significantly lower (P < 0.001 at pH 5.0; P = 0.008 at pH 7.0) than when the strain was grown without a competitor (Fig. 2B).

Ochromonas sp. showed a continuous weak increase from the third to the last day of the experiment conducted at neutral pH (Fig. 1D). Growth rate calculated from the short exponential phase between days 2 and 4 was 0.49 d−1, which is not significantly different from the single growth experiment (Fig. 2A). At pH 5.0, cell numbers of Ochromonas sp. remained constant between days 2 and 3, and then increased to reach final cell numbers that were close to the initial abundances (Fig. 1C). The linear regression yielded μ = 0.44 d−1 during days 3–6, i.e. growth of Ochromonas sp. was drastically reduced compared to its growth rate measured in the respective single species experiment (Fig. 2A). Both at pH 5.0 and 7.0, the final population sizes of Ochromonas sp. were several times lower than those of P. malhamensis.

Bacterial abundances ranged from 0.8 × 106 to 10.7 × 106 cells ml−1 in the course of the various experiments (Table 1). In all experiments, the final bacterial abundance exceeded the initial bacterial cell numbers.

Table 1.

Bacterial abundance (in 106 ml−1) in the course of the experiments. The data shown are mean values of triplicates ± 1 SD.

| pH |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (d) | 2.5 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 7.0 |

| 0 | 1.10 | 1.26 | 3.55 | 2.58 |

| 1 | 1.40 ± 0.41 | 2.10 ± 1.46 | 2.45 ± 0.17 | 10.70 ± 6.64 |

| 2 | 0.87 ± 0.24 | 5.36 ± 2.78 | 2.62 ± 1.02 | 7.04 ± 1.68 |

| 3 | 1.03 ± 0.34 | 10.20 ± 5.04 | 6.56 ± 2.53 | 5.33 ± 0.44 |

| 4 | 0.82 ± 0.13 | 10.60 ± 5.13 | 3.40 ± 0.97 | 4.51 ± 1.78 |

| 6 | 1.64 ± 0.17 | 6.86 ± 3.45 | 2.70 ± 1.71 | 4.81 ± 1.99 |

| 7 | 1.36 ± 0.28 | 3.67 ± 2.12 | 10.40 ± 3.27 | 4.91 ± 1.19 |

Discussion

Although pH is a major environmental factor limiting the distribution of protist species in aquatic habitats (Packroff and Woelfl 2000; Weisse 2006), only a few studies investigated the pH response of protists experimentally (Boenigk 2008; Weisse and Stadler 2006; Weisse et al. 2007; this study). We reported the pH response of the two species used in the present study and another Ochromonas sp. isolated from a similar AML in Germany in a previous study (Moser and Weisse 2011a). This earlier work revealed that the Ochromonas sp. strain from Langau showed maximum growth rates at pH 4–5 (μ = 1.41 ± 0.19 d−1) when grown alone. Growth rates of P. malhamensis peaked at pH 7.0 (μ = 0.73 ± 0.09 d−1) in these single strain experiments. Growth rates of Ochromonas sp. were significantly higher than that of P. malhamensis at all pH tested (2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0 and 7.0) except at pH 3.5 and 7.0 (Moser and Weisse 2011a).

Resource competition has been identified as a key process shaping the structure of aquatic food webs (Belgrano et al. 2005; Gliwicz 2003) and has been studied experimentally since the pioneering work of Gause (1932, 1934). Several decades later, competition was studied in much detail with freshwater autotrophic protists testing Tilman's mechanistic resource competition theory (Tilman 1977, 1981). However, studies dealing with competition between heterotrophic and mixotrophic protists, and between protists and multicellular organisms are still rare. Rothhaupt (1996) demonstrated experimentally that Ochromonas sp. is able to outcompete obligate bacterivorous flagellates in the light. Following up this study, Tittel et al. (2003) reported that an Ochromonas sp. strain isolated from an AML in Germany (pH 2.6–3.3) is able to reduce its phagotrophic competitor, the ciliate Oxytricha sp., to low numbers in the light. These authors also reported a strong reduction of the flagellate's bacterial and algal prey in illuminated surface strata of its habitat.

To our knowledge this is the first study analyzing the competition of two different, but closely related chrysomonad species in relation to pH. Since we know from our earlier experiments (Moser and Weisse 2011a) that both species can survive at the entire pH range from 2.5 to 7.0, the conditions for coexistence are met. It did not astonish that Ochromonas sp. dominated over P. malhamensis at pH 2.5 and that the latter performed better than the former at pH 7.0 because Ochromonas sp. originated from a highly acidic environment and P. malhamensis was isolated from a circumneutral lake. The main question was what will happen when the two flagellate strains live in competition with each other under moderately to highly acidic conditions? At pH 3.5, growth rates of Ochromonas sp. were slightly higher than that of P. malhamensis, thus confirming qualitatively our results measured in the single species treatments (Fig. 2). Competition reduced μ of both species at a similar rate, compared to the single species experiments. Accordingly, the two chrysomonads coexisted at pH 3.5. Based upon our earlier results (Moser and Weisse 2011a), Ochromonas sp. should be the superior competitor in the competition experiments at pH 5.0 (Fig. 2). Contrary to expectations, both species reached similar growth rates and coexisted during the experiment (Fig. 1C). The growth rate of P. malhamensis was more constant and less reduced than that of Ochromonas sp., relative to the respective growth rates measured in the single species experiments (Fig. 2). It appears unlikely that the numerical dominance of P. malhamensis at pH 5.0 was due to exploitative competition because this would imply that bacterial levels fell below the satiating concentrations in the course of the experiments. This was not the case in our experiments, because bacterial abundances remained at >2 × 106 cells ml−1 in all experiments conducted at pH 5.0. Final bacterial cell numbers even exceeded the initial abundances (Table 1). However, since we did not assess the bacterial species composition, we cannot rule out that some palatable bacterial strains were reduced in the course of the experiment.

Caron et al. (1990) reported a bacterial threshold abundance of ∼1 × 106 ml−1, above which P. malhamensis switched nearly completely from phototrophic growth to heterotrophic growth. Sanders et al. (1990) measured slow growth (μ ≤ 0.3 d−1) of P. malhamensis when grown phototrophically; even the maximum rate of photosynthesis accounted for only 7% of the total carbon budget of this mixotroph when sufficient bacteria were present. Sanders et al. (1990) considered phototrophic nutrition to be an evolutionary strategy for long-term survival of P. malhamensis. While light intensity and pH ranging from 4.0 to 7.9 had no effect on phagotrophy, bacterial density was the primary factor influencing phagotrophic growth (Sanders et al. 1990). In our study, the bacterial concentrations did not fall below the reported threshold in the treatments at pH 3.5, 5.0, and 7.0 at any time. Similar to P. malhamensis, the preferred nutritional mode of Ochromonas sp. isolated from AML is phagotrophy, both in the light and in the dark (Boëchat et al. 2007; Schmidtke et al. 2006; Tittel et al. 2003). We conclude that both flagellates behaved phagotrophically in the experiments reported in this study. Only in the experiment conducted at pH 2.5, bacterial abundance was close to and sometimes even below the threshold of 106 bacteria ml−1. Similar to Sanders et al. (1990), we observed survival but only negligible growth of P. malhamensis at this low bacterial level. We conclude that P. malhamensis cannot reach sustainable growth if bacteria drop below 106 cells ml−1 and light is limiting photosynthesis (<100 μmol m−2 s−1).

In spite of the low food concentration, Ochromonas sp. reached in the competition experiment at pH 2.5 its growth rate measured in the single species experiments at the same pH (Fig. 2A). In the upper 5 m of the AML at Langau, bacterial cell numbers ranged from 105 to 3 × 105 cells ml−1 (Moser and Weisse 2011b); bacterial biomass varied from 0.9 to 5.7 μg C L−1 (Weithoff et al. 2010). An inverse relationship between bacterial biomass and biomass of Ochromonas spp. observed in three AML suggests that grazing by Ochromonas spp. is controlling bacterial biomass and keeping bacteria at low level in the AML at Langau (Kamjunke et al. 2004; Weithoff et al. 2010). The experimental results and the in situ observations provide evidence that Ochromonas sp. is better adapted to low bacterial concentrations than P. malhamensis.

Previous single species experiments had shown that these flagellates begin to grow exponentially almost immediately after inoculation at comparable initial cell numbers as used in the present study (Moser and Weisse 2011a). In contrast to the previous results, flagellate cell numbers declined at the beginning of the pairwise growth experiments of the present study, in particular at the higher pH (Fig. 1C and D). Poterioochromonas malhamensis is known to be cannibalistic (Caron et al. 1990) and can also ingest algae and other flagellates that may be even larger than itself (Pringsheim 1952; Zhang and Watanabe 2001). Similarly, an Ochromonas sp. isolated from an AML in Germany that is closely related to the Ochromonas sp. strain used in the present investigation (Moser and Weisse 2011a) feeds on the larger green alga Chlamydomonas sp. (Kamjunke et al. 2004; Tittel et al. 2003). Predation might thus be responsible for the reduction of the flagellates observed at the beginning of the experiments at the two highest pH.

Another factor that may have played a role in the competition experiments is allelopathy. Allelopathic effects are known from species of both genera, i.e. Ochromonas and Poterioochromonas (Blom and Pernthaler 2010; Boenigk and Stadler 2004). The production and excretion of allelopathic secondary metabolites of P. malhamensis has toxic effects on rotifers that do not require ingestion of the flagellate (Boxhorn et al. 1998). Boenigk and Stadler (2004) reported that heterotrophic and mixotrophic strains of these chrysomonads were toxic to zooplankton at abundances exceeding 104 flagellates ml−1. In our experiments the flagellate abundances always exceeded the threshold of 104 cells ml−1. Recently, Blom and Pernthaler (2010) demonstrated that metabolites of P. malhamensis may selectively affect the growth of some aquatic bacteria even in very small doses. Therefore, we cannot rule out that allelopathic secondary metabolites of the two flagellate strains influenced each other either directly or indirectly, via their bacterial prey, in our competition experiments.

The results obtained support our hypothesis that, because Ochromonas sp. is an inferior competitor under neutral to moderately acidic conditions, it must take refuge from competition in inhospitable habitats such as AML. We conclude that the competitive ability of Ochromonas sp. increases under suboptimal pH conditions because its potential competitors are affected more strongly by the adverse conditions including low food levels. The competitors may have a higher bacterial threshold for phagotrophy than Ochromonas sp. Ochromonas sp. dominated over P. malhamensis only at the lowest pH tested (2.5) that was close to the pH of its habitat of origin. Our results suggest that P. malhamensis may be excluded from highly acidic environments if acidophilic or acidotolerant species such as Ochromonas sp. are present. To our knowledge, the genus Poterioochromonas has not yet been reported from extremely acidic mining lakes (pH < 3) (reviewed by Packroff and Woelfl (2000)).

The lack of more efficient competitors has been postulated as the primary reason for the observed shift in the rotifer and crustacean species community with decreasing pH (Deneke 2000; Wollmann et al. 2000). We provide the first experimental evidence that acidotolerant protist species may also benefit from competitive release under acidic stress.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Stadler and U. Scheffel for technical assistance in the laboratory. This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF Project P20118-B17).

References

- Aaronson S., Baker H. A comparative biochemical study of two species of Ochromonas. J. Protozool. 1959;6:282–284. [Google Scholar]

- Belgrano A., Scharler U.M., Dunne J., Ulanowicz R.E. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2005. Aquatic Food Webs – An Ecosystem Approach. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S.J., Sanders R.W., Porter K.G. Heterotrophic, autotrophic, and mixotrophic nanoflagellates: seasonal abundances and bacterivory in a eutrophic lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1990;35:1821–1832. [Google Scholar]

- Blom J., Pernthaler J. Antibiotic effects of three strains of chrysophytes (Ochromonas, Poterioochromonas) on freshwater bacterial isolates. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010;71:281–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boëchat I.G., Weithoff G., Krüger A., Gücker B., Adrian R. A biochemical explanation for the success of mixotrophy in the flagellate Ochromonas sp. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2007;52:1624–1632. [Google Scholar]

- Boenigk J., Stadler P. Potential toxicity of chrysophytes affiliated with Poterioochromonas and related ‘Spumella-like’ flagellates. J. Plankton Res. 2004;26:1507–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Boenigk J., Pfandl K., Stadler P., Chatzinotas A. High diversity of the ‘Spumella-like’ flagellates: an investigation based on the SSU rRNA gene sequences of isolates from habitats located in six different geographic regions. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;7:685–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boenigk J. Nanoflagellates: functional groups and intraspecific variation. Denisia. 2008;23:331–335. [Google Scholar]

- Boxhorn J.E., Holen D.A., Boraas M.E. Toxicity of the chrysophyte flagellate Poterioochromonas malhamenis to the rotifer Brachionus angularis. Hydrobiologia. 1998;387/388:283–287. [Google Scholar]

- Caron D.A., Porter K.G., Sanders R.W. Carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus budgets for the mixotrophic phytoflagellate Poterioochromonas malhamensis (Chrysophyceae) during bacterial ingestion. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1990;35:433–443. [Google Scholar]

- Deneke R. Review of rotifers and crustaceans in highly acidic environments of pH values <3. Hydrobiologia. 2000;433:167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Gaedke U., Kamjunke N. Structural and functional properties of low- and high-diversity planktonic food webs. J. Plankton Res. 2006;28:707–718. [Google Scholar]

- Gasol J.M., del Giorgio P.A. Using flow cytometry for counting natural planktonic bacteria and understanding the structure of planktonic bacterial communities. Sci. Mar. 2000;64:197–224. [Google Scholar]

- Gause G.F. Experimental studies on the struggle for existence. I. Mixed populations of two species of yeast. J. Exp. Biol. 1932;9:389–402. [Google Scholar]

- Gause G.J. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore: 1934. The Struggle for Existence. [Google Scholar]

- Geller W., Klapper H., Salomons W. Springer; New York: 1998. Acidic Mining Lakes: Acid Mine Drainage, Limnology and Reclamation. [Google Scholar]

- Gliwicz Z.M. Zooplankton. In: O'Sullivan P., Reynolds C.S., editors. The Lakes Handbook. Blackwell Science Ltd.; Oxford: 2003. pp. 461–516. [Google Scholar]

- Gross W. Ecophysiology of algae living in highly acidic environments. Hydrobiologia. 2000;433:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jones R.I. Mixotrophy in planktonic protists as a spectrum of nutritional strategies. Mar. Microb. Food Webs. 1994;8:87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kamjunke N., Gaedke U., Tittel J., Weithoff G., Bell E.M. Strong vertical differences in the plankton composition of an extremely acidic lake. Arch. Hydrobiol. 2004;161:289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, M., Weisse, T., 2011a. Combined stress effect of pH and temperature narrows the niche width of flagellates in acid mining lakes. J. Plankton Res. 33, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moser, M., Weisse, T., 2011b. The most acidified Austrian lake in comparison to a neutralized mining lake. Limnologica 42, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nixdorf B., Mischke U., Leßmann D. Chrysophytes and chlamydomonads: pioneer colonists in extremely acidic ming lakes (pH > 3) in Lusatia (Germany) Hydrobiologia. 1998;369/370:315–327. [Google Scholar]

- Packroff G., Woelfl S. A review on the occurrence and taxonomy of heterotrophic protists in extreme acidic environments of pH values <3. Hydrobiologia. 2000;433:153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Pringsheim E.G. On the nutrition of Ochromonas. Q. J. Microsc. Sci. 1952;93:71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rothhaupt K.O. Laboratory experiments with a mixotrophic chrysophyte and obligately phagotrophic and phototrophic competitors. Ecology. 1996;77:716–724. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders R.W., Porter K.G., Caron D.A. Relationship between phototrophy and phagotrophy in the mixotrophic chrysophyte Poterioochromonas malhamensis. Microb. Ecol. 1990;19:97–109. doi: 10.1007/BF02015056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandgren C.D. The ecology of chrysophyte flagellates: their growth and perennation strategies as freshwater phytoplankton. In: Sandgren C.D., editor. Growth and Reproductive Strategies of Freshwater Phytoplankton. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1988. pp. 9–104. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtke A., Bell E.M., Weithoff G. Potential grazing impact of the mixotrophic flagellate Ochromonas sp. (Chrysophyceae) on bacteria in an extremely acidic lake. J. Plankton Res. 2006;28:991–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Stabel H.-H. Chemical composition and drinking water quality of the water from Lake Constance. Arch. Hydrobiol. Spec. Issues Adv. Limnol. 1998;53:13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tilman D. Resource competition between planktonic algae: an experimental approach. Ecology. 1977;58:338–348. [Google Scholar]

- Tilman D. Test of resource competition theory using four species of Lake Michigan algae. Ecology. 1981;62:802–815. [Google Scholar]

- Tittel J., Bissinger V., Zippel B., Gaedke U., Bell E., Lorke A., Kamjunke N. Mixotrophs combine resource use to outcompete specialists: implications for aquatic food webs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:12776–12781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2130696100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisse T. Freshwater ciliates as ecophysiological model organisms – lessons from Daphnia, major achievements, and future perspectives. Arch. Hydrobiol. 2006;167:371–402. [Google Scholar]

- Weisse T., Stadler P. Effect of pH on growth, cell volume, and production of freshwater ciliates, and implications for their distribution. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2006;51:1708–1715. [Google Scholar]

- Weisse T., Scheffel U., Stadler P., Foissner W. Local adaptation among geographically distant clones of the cosmopolitan freshwater ciliate Meseres corlissi. II. Response to pH. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2007;47:289–297. [Google Scholar]

- Weithoff G., Moser M., Kamjunke N., Gaedke U., Weisse T. Lake morphometry strongly shapes the plankton community structure in acidic mining lakes. Limnologica. 2010;40:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.limno.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollmann K., Deneke R., Nixdorf B., Packroff G. Dynamics of planktonic food webs in three mining lakes across a pH gradient (pH 2–4) Hydrobiologia. 2000;433:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Watanabe M.M. Grazing and growth of the mixotrophic chrysomonad Poterioochromonas malhamensis (Chrysophyceae) feeding on algae. J. Phycol. 2001;37:738–743. [Google Scholar]