Abstract

Data communication via Low-Earth-Orbit Satellites between portable hydro-meteorological measuring stations is the backbone of our system. This networking allows automated event sampling with short time increments also for E.coli field analysis. All activities of the course of the event-sampling can be observed on an internet platform based on a Linux-Server. Conventionally taken samples by hand compared with the auto-sampling procedure revealed corresponding results and were in agreement to the ISO 9308-1 reference method. E.coli concentrations were individually corrected by event specific die-off rates (0.10–0.14 day−1) compensating losses due to sample storage at spring temperature in the auto sampler.

Two large summer events 2005/2006 at a large alpine karst spring (LKAS2) were monitored including detailed analysis of E.coli dynamics (n = 271) together with comprehensive hydrological characterisations. High resolution time series demonstrated a sudden increase of E.coli concentrations in spring water (approx. 2 log10 units) with a specific time delay after the beginning of the event. Statistical analysis suggested the spectral absorbent coefficient measured at 254nm (SAC254) as an early warning surrogate for real time monitoring of faecal input. Together with the LEO-Satellite based system it is a helpful tool for Early-Warning-Systems in the field of drinking water protection.

Keywords: Microbiological Event Sampling, Faecal Indicator, Decision Support System, Quality Management, LEO-Satellite Communication, Early Warning Systems, Drinking Water Protection

INTRODUCTION

Global changes in ecosystems, the growth of population as well as modifications of the legal framework, such as within the EU, caused in the last years an increasing requirement of qualitative groundwater and spring water monitoring with the target to supply the consumers also in future with high-quality raw water with minimal further treatment requirements for drinking water production. Also the demand of sustainable protection of drinking water resources caused the enhanced implementation of early warning systems and quality assurance networks in water supplies.

Alpine karst aquifers are important but sensitive water resources. According to this situation, strong precipitation in alpine catchments can lead to a quick contamination of spring water due to the input of faecal material from respective surface locations with human (e.g. settlements, tourism), wildlife, and/or agricultural (e.g. summer pastures) influence (Kralik et al. 2001). According to the epidemiological situation, contamination of water with faecal material is of high significance being associated with the potential occurrence of enteric pathogens (WHO, 2004). Faecal contamination is most suitable detected by the use of microbiological faecal indicators (FI) (Bonde 1963; Geldreich 1978). Recently, Escherichia coli (E.coli) revealed to be the most suitable FI for the sensitive detection of recent faecal input in alpine karstic spring water. In contrast to enterococci and Clostridium perfringens, E.coli was prevalent in all potential human, wildlife, and agricultural faecal source in high and comparable concentrations (i.e. average log10 7.2 – log10 8.0 CFU per g faeces). E.coli was thus suggested as a very suitable FI for the sensitive detection of faecal pollution input by surface runoff into alpine karstic springs (Farnleitner et al. 2005a).

In the field of hydrogeological investigations event monitoring and event sampling are indispensable tools to get detailed information about parameters of the aquifer and its vulnerability, storage dynamics and runoff characteristics. Conventional microbiological water analysis is based on manually taken samples, subsequent transport to a specialised lab environment and analysis within a certain period of time. However, due to the high logistic efforts, sampling intervals are usually rather long and can hardly give realistic information about the temporal dynamics of the respective microbial water quality. It is well known that microbial loads can increase by orders of magnitudes in freshwater resources during periods of increased discharge and surface runoff conditions (e.g. Ferguson, et al. 1996). However, appropriate information on the temporal dynamics of faecal pollution is a basic requirement for optimised water management (Kay et al. 2007), such as to divert spring water from water supply only in case, when set quality thresholds are exceeded.

Although alpine karstic spring water represent important drinking water resources, information on the dynamics of microbial faecal pollution during periods of increased discharge and event situations were hardly availably in the past. The reason for this gap of knowledge is simply explainable because suitable approaches for in-field monitoring were not available. The aim of this work was thus, i) to establish a practical technology for automatic high-resolution microbiological event sampling and corresponding field analysis for E.coli, ii) to evaluate its comparability to ISO standard procedures and, iii) to gather first data on the temporal dynamics of E.coli during “worst case” summer events combined with detailed hydrological information about a representative alpine karstic catchment area of the LKAS2 (Farnleitner et al. 2005b).

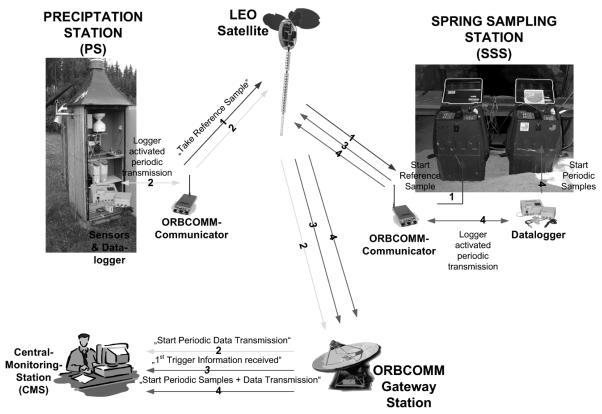

The system, which is presented here, enables fully automated event sampling and real-time availability of data. By means of networking via Low Earth Orbiting Satellites data from the precipitation station (PS) in the catchment area are brought together with data of the spring sampling station (SSS) without the need of terrestrial infrastructure for communication and power supply. Therefore a completely automated event sampling procedure is made possible. Furthermore the whole course of input and output parameters, like precipitation (input system) and discharge (output system) and the status of the sampling system, is transmitted via LEO-Satellites to a Central Monitoring Station (CMS) which can be linked with a web-server to have unlimited real-time data access. The automatically generated notice of event to a local service team of the sampling station is transmitted in combination with internet, GSM, GPRS or LEO-Satellites.

ORBCOMM SATELLITE SYSTEM

Based on extensive technical and cost comparisons and on validation measurements, e.g. (Skritek et al. 2001, Stadler & Skritek 2002), the ORBCOMM LEO Satellite system was chosen. ORBCOMM is a “Little-LEO” system, with 30 servicing satellites in 6 orbit planes of 800km altitude. It provides bi-directional “short message” data-transfer at 2.4/4.8 kbps, with data blocks preferably less than some 100 Bytes. ORBCOMM operates at frequencies about 140 MHz, providing large satellite footprints, and requires only low-cost/low-power equipment, allowing, e.g., simple whip-antennas as well as small solar-panels for power supply and transmission even from forests. ORBCOMM satellite modems are smart transceivers that include a user programmable microcontroller with several I/O-lines and AD-/DA-converters (also with GPS-receiver) and can be used as “stand alone” data-acquisition systems.

The ORBCOMM modem transmits its data to the satellite, from where down-link transmission is performed either directly to one of the Gateway Earth Stations (GES) or as “globalgrams” (data stored in the satellite and forwarded to earth when the satellite passes the desired GES). The GES emails the data to the receiver via internet or re-transmits it to any “nomadic” ORBCOMM modem again via satellite.

Although the ORBCOMM system covers the entire globe, “visibility gaps” may occur between satellite passes. Best-case locations, however, showed about 70% “satellite-in-view” and average transmission delays of only 3 minutes (Skritek & Pfliegl 2002). Further measurements and simulations of satellite gaps for environmental applications are reported e.g. in (Stadler & Skritek 2004).

Assembling, cross-linked Stations and Data Streams

The precipitation station (PS) is located in the catchment area of the spring, where the event sampling will be conduced. It is equipped with a tipping bucket, a data logger and a LEO-Satellite modem. It can be supplemented with additional meteorological sensors and sampling devices. The monitoring and sampling site at the spring (spring sampling station, SSS) is equipped with an additional data logger, a pressure probe to register the changing of discharge, two automatic sampling units (one for the reference sample and one for the periodic samples) and a LEO-Satellite modem for real-time control and data transmission. It can be supplemented with additional hydrological or meteorological sensors.

Stream of data and information

As soon as the trigger-level is exceeded in the catchment area at the PS (predefined amount of precipitation in a definite period, both parameters are selectable) a trigger report is sent to the SMS via satellite. There the reference sample is taken automatically. In addition, the PS starts sending via LEO-Satellite continuously data about the rainfall to the CMS. The SMS is now ready to wait, until the second trigger-level (increase of discharge, also programmable), is exceeded. If this happens, the periodic sampling within the event sampling starts automatically and the status information and measured values are continuously sent via satellite to the CMS and the local service team is informed.

Precipitation Station (PS)

It records rainfall and other meteorological data. From the intensity and the recorded amount of precipitation a specific trigger criterion is derived. If this trigger-level is exceeded, the PS activates one or more SSS via satellite (Data Stream 1, Fig. 1) to take the reference sample. This happens before the event affects the discharge of the spring. The CMS is also informed via satellite by receiving periodic data sets from the PS to observe the further trend of precipitation (Data Stream 2, Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Block-Diagram of Assembling. Stream of data and information of an event-triggered LEO Satellite Hydrology Network

Spring Sampling Station (SSS)

As soon as the activation data-set is received, the automatic sampling unit takes the reference sample. The status is sent to the CMS (Data Stream 3, Fig. 1). This procedure can be repeated several times, depending on the number of sampling bottles in the automatic sampling device. This is necessary because due to the hydrological boundary conditions the upcoming event at the spring is worth sampling.

Now the SSS is waiting during a specified period of time for the increase of the discharge, which is the second trigger event. The trigger level is derived from the increase of the gauge height within a period of time and is chosen according to the characteristics of the spring. This trigger criterion is activated from the data logger. If the predefined trigger level is exceeded, periodic sampling is started automatically. The information is sent via satellite to the CMS. The SSS starts also periodic data transmission to the CMS to trace this event (Data Stream 4, Fig. 1).

Central Monitoring Station (CMS) and Web-Interface

There the information from all stations is collected. Additionally the local service team is informed from the CMS automatically of important facts like starting of rainfall (1st trigger) and starting of the sampling procedure at the SSS (2nd trigger) via GSM cell phones. Depending on the sampling time increment and the number of bottles in the automatic samplers, they can predict their next visit at the SSS to maintain the station.

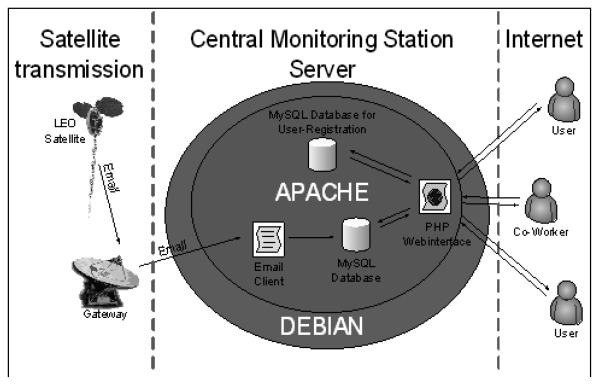

The CMS provides an online Internet-Portal for access to these environmental data (Fig. 2). It is built around the server-based operating system Debian, which is a stable free software, providing perfect interaction and performance with the server. Among others, the server comprises a RAID-system for fault-tolerant operation.

Figure 2.

Components and Activities at the Central Monitoring Station (CMS)

A dedicated email-client was developed to decode and extract the compressed measurement data sets and to store them into the integrated MySQL database. For this purpose Perl was used as the programming language, which allows very efficient coding.

The email-client is fully automated and dynamically coded, so no user defaults are needed for this stand-alone program. The client is also very easy to handle if additional measurement stations should be integrated into the system. It provides flexible and simple configuration e.g., for individual number of stations, types and coding of input data-sets. Additionally, the client automatically detects incorrect emails (syntax check) and stores them in a specific data-base table. In this case, it can also automatically send an information mail to the user on this error.

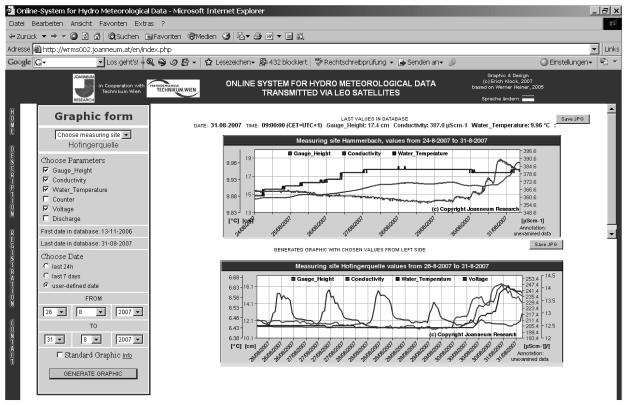

To provide on-line communication with access to the stored measurement data via the Internet, an ApacheWeb server was implemented on the Debian-Server. The dynamically generated online website can be viewed under http://wrms002.joanneum.at. The start-page is shown in Figure 3. The freeware PHP was used for programming these interactions between the Internet users and the CMS. Furthermore, PHP can also interpret other interface languages, e.g., XML or JavaScript, using standardized modules, which makes the chosen implementation very flexible for on-line environmental communication.

Figure 3.

Dynamically generated Website for Online Data

Additional to the online graphical presentation, all co-workers and public access users may also download these graphics to their local machine. Using password-protection, several access levels to the data and visualization are feasible for different user groups, e.g., general public access to environmental information vs. individual access for specific in-depth data for research-project co-workers.

HYDROLOGICAL CHARACTERIZATION AND METHODS

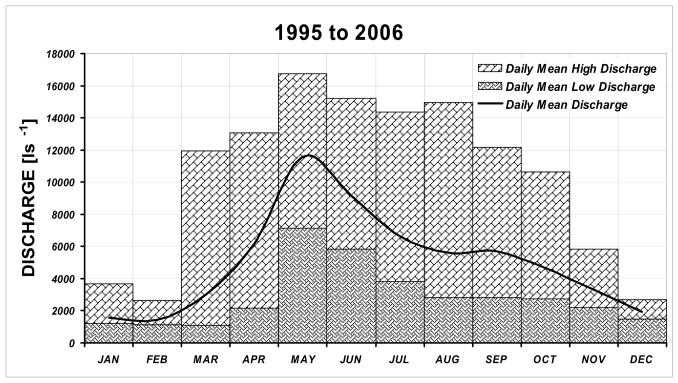

Event sampling campaigns were conduced in 2005 and 2006 at a karst spring (LKAS2) of a triassic limestone aquifer in the Northern Calcareous Alps. The mean discharge is 4.8 m3s−1. As a typical karst spring, the variability of discharge is very high and ranges from 0.4 to approximately 40 m3s−1, this represents daily mean discharges from 1 to 22.7 m3s−1 (shown in Figure 4). More detailed descriptions of the event are compiled in the chapter “Results”.

Figure 4.

Daily Mean Discharge at LKAS2

The events started after heavy summer thunderstorms or weather front passages with more than 25 mm precipitation at the first day. The response time (i.e. time between beginning of rainfall in the catchment area and increasing of the discharge of the spring) was between 2 hours 45 minutes and 12 hours and 45 minutes, corresponding to the hydrological circumstances.

Precipitation was measured with a ARG100 tipping bucket with a resolution of 0.2 mm and registered every 15 minutes with a GEALOG-Compact from Logotronic (Vienna, Austria). Discharge (pressure probe PDCR1830 from Druck, London), electrical conductivity and water temperature (WTW Tetracon 325sensor from WTW, Weilheim, Germany) were registered with GEALOG-S System (Logotronic, Vienna, Austria) with a time increment of 15 minutes. Turbidity and SAC254 were registered every 10 minutes with s::can sensors with integrated data logger(s::can, Vienna, Austria). The ORBCOMM data communication was performed by PANASONIC Satellite modems KX-G7101 (Fukuoka, Japan)

MICROBIOLOGICAL METHODS

Sampling and analysis of E.coli

Sterilized glass bottles (1 litre) were used for conventional microbiological sampling by hand. An amount of 100 ml of water was then aseptically transferred from the filled glass bottle into a sterile disposable 120 ml plastic vessel (IDEXX, Germany) used for corresponding E.coli in-field analysis by Colilert-18 (IDEXX, Germany) according to manufactures procedures (http://www.idex.com.water). The glass bottles with the remaining rest of the water sample (approx. 900 ml) was immediately transported to the laboratory (dark conditions, 4°C) and processed accordingly to ISO 9308-1 (E.coli enumeration by membrane filtration). For automatic sampling procedures at the spring outlet, 24 sterile disposable plastic vessels (120ml, IDEXX) were directly positioned in the automatic sampling device. Samples were recovered from auto-sampler at least all 24 h and analysed immediately by Colilert-18. The time span between sampling by the auto-sampler and the time of analysis by Coliert-18 were recorded for each collected sample (i.e. storage time). Individual storage times were used to estimate and to correct for concentration losses by E.coli die off (see below). In addition, a maximal time span difference of 15 minutes was accepted for auto-sampling vs. manually taken spring samples in order evaluate automatic sampling procedures by in-field Colilert-18 analysis.

E.coli die off during sample storage

To estimate E.coli die off during sample storage in the auto-sampling device (maximum sample storage up to 24h), microcosm experiments at sample storage conditions were performed. For this purpose, 3 sterile plastic gallons (4,2 litre) were filled with spring water collected during the event and stored at ambient spring water conditions in the dark directly at the spring outlet. Reduction of E.coli counts were determined all 4 to 7 days by Colilert-18 until E.coli was no longer detectable. Bottles were thoroughly shaken before sampling in order to suspend sediment particles. For die off rate calculations E.coli counts were ln transformed and subjected to regression analysis. All calculations were performed by Excel and SPSS 13. Die off rates were then used to correct recovered E.coli dynamics for the summer events 2005 and 2006 by the formula Nx = N0 exp (ts × die off rate), where Nx equals culture based counts at time x after storage, N0 equals culture based counts immediately determined after sampling, and ts is the respective storage time at the ambient spring water temperature.

RESULTS

Evaluation of microbiological methods for event analysis

Evaluation of E.coli field enumeration

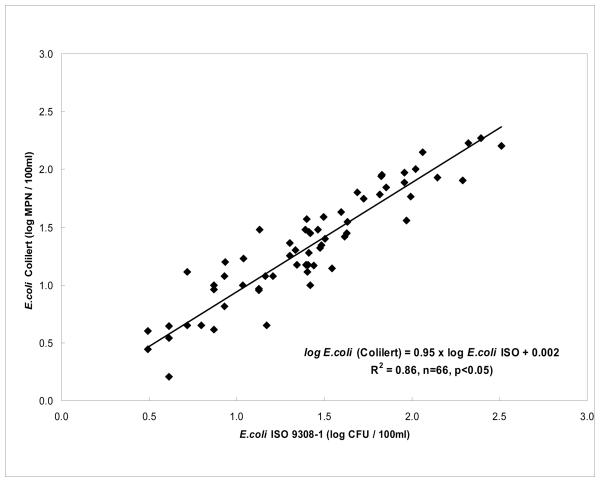

Comparison of Colilert-18 (in-field determinations) with the standard ISO 9308-1 laboratory approach performed for corresponding spring water samples collected during summer season and 2005/2006 events yielded a high agreement for E.coli enumeration for the studied concentration range between 3 and 300 CFUs (Fig. 5). Regression analysis only revealed a slightly higher trend in sensitivity at increasing contamination levels for the ISO-9308-1 approach (i.e. slope = 0.95). This is probably explainable by the intrinsic features of the ISO-9308-1 cultivation media, being optimised for high sensitivity rather then for specificity to detect also stressed but viable E.coli in water even after extended treatment processes (ISO 9308-1). The high agreement of both enumeration methods supports previous results recovered from other ground and surface aquatic habitats (Niemela et al. 2003). Our results clearly demonstrate that field analysis for E.coli by Colilert-18 yields comparable results with the acknowledged ISO standard procedure for alpine karstic water resources and can thus be comparably applied and recommended for in-field monitoring activities in such locations.

Figure 5.

Comparative analysis of ISO9308-1 vs. Colilert E.coli detection.

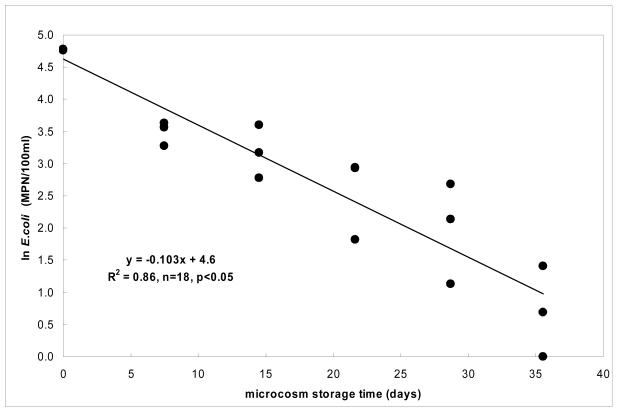

E.coli die off in stored spring water samples at ambient spring temperatures

Performed die off microcosm experiments revealed reproducible results for both investigated summer events. A linear regression model could be fitted to the ln transformed E.coli MPN, indicating that a first order die off kinetic was justified to describe the overall reduction process with time in the stored spring water samples, as representatively shown for 2005 (Fig. 6). The calculated die off rates of −0.10 per day (event 2005) and −0.14 per day (event 2006, n=18, p<0.05) correspond to half life constants (HLC) of 5 to 7 days. The estimated HLC appear very reasonable taking the considered ambient spring and storage temperatures (approx. 5°C) and the oligotrophic nature of the spring water, encompassing a very low grazing pressure by protozoan predators, into account (Farnleitner et al. 2006). Estimated die off rates imply that the underestimation bias of E.coli keeps ≤ 5% if analysis takes place within 8h of sample collection. However, storage of samples over 24h cause an underestimation bias up to 13% and correction efforts using respective storage times and event specific die off kinetics are thus recommendable for storage periods > 8h.

Figure 6.

Die off behaviour of E.coli MPN in spring water stored at 5.1°C (event 2005).

Comparison of E.coli counts from auto-sampling vs. manually taken samples (incremental sampling)

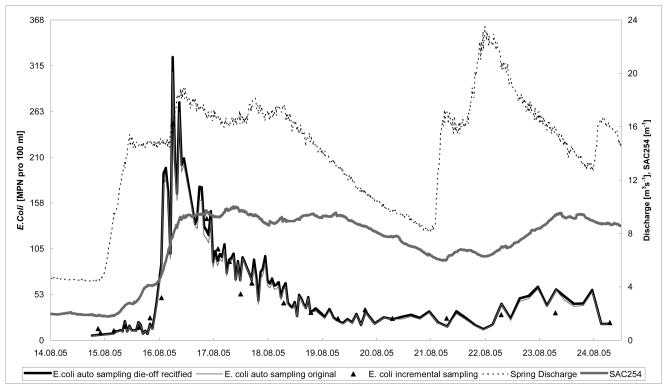

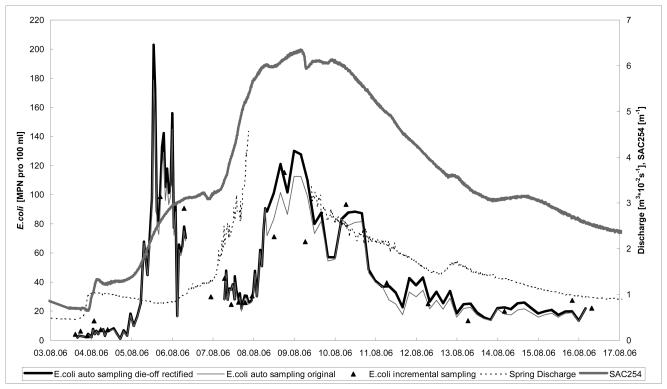

In order to evaluate the in situ performance of the auto-sampling approach, a limited number of parallel determinations (n = 52) were also derived from manually taken spring water during the 2005/2006 events. Except two outliers, incremental sampling for E.coli by conventionally taken samples corresponded well to the high resolution graph recovered by the auto-sampling procedure (Fig. 7a, 7b, filled triangles). This is further supported by a more detailed correlation analysis for selected couples of comparisons not differing more than 15 minutes in sampling time (E.coli automatic sampling = 0.99×incremental sampling+4.8, n=27, p<0.05, R2=81). However, it should be mentioned, that an exact agreement by correlation analysis is not to be expected because corresponding samples could not be taken exactly at the same point of time, thus being influenced by short-term temporal variation of microbial spring water quality.

Figure 7a.

Time series of the summer event 2005. E.coli MPN, discharge and SAC254

Figure 7b.

Time series of the summer event 2006. E.coli MPN, discharge and SAC254

Event monitoring by auto-sampling and E.coli field enumeration

Conventional hydrological parameters

The recovered summer spring events are shown in Figure 7 a, b. Accordant to the typical behaviour of alpine karst springs, the traditional hydrological quality parameters turbidity and SAC254 showed different behaviour. Turbidity rose more or less parallel with the discharge, whereas SAC254 raised later, especially in the first phase of the event. Based on these measuring results, turbidity can be explained as part of the karst-system, coming mainly from the cave sediments, whereas SAC254 is highly correlated to organic input from the land-cover. The event 2006 was caused by extensive rainfall by more than 165 mm m−2 and the following flood event caused some data loss, which is also seen in Fig 7b.

Microbiological monitoring

Due to the short time increments of the automated sampling approach, the whole temporal dynamics of E.coli MPN in spring water during the investigated event phases could be recovered (n=271 for automatic samplings replicates). Correction of E.coli MPN for die off losses during auto-sampler storage did not alter the graphs dramatically (maximum of 24h storage), but increased the FI dynamics somewhat (c.f. Fig. 7b). A significant time delay between the first raise of the discharge and the increase of E.coli MPN became obvious for both events (23:30 hours to 24:20 hours time delay). This observation can be explained by transport models based on “piston-flow” effects, where stored water in karst conduits is activated by hydraulic pressure and affects the first rising of discharge, but mass transport from the land cover last considerable longer. After the observed delay E.coli MPN increased dramatically by almost two orders of magnitude within a very short period of time (19 hours in 2005, 9 hours during the 2006 event). For the event 2005 also a first-flush effect was obvious, showing a strong transfer of FI into the aquifer for the first increase of the discharge (15. Aug. 2005 - 17. Aug. 2005), whereas no significant increase of E.coli MPN during the second discharge event could be observed (21. Aug. 2005 - 24. Aug. 2005). Although some characteristics of the two monitored events are obvious, characterization of events has to comprise additional observations, basically hydro-meteorological parameters. This connotes also, that transferring this tool to other springs in different areas with divergent aquifer and drainage basin characteristics it is essential that it is proofed and adjusted.

DISCUSSION AND FURTHER DEVELOPMENTS

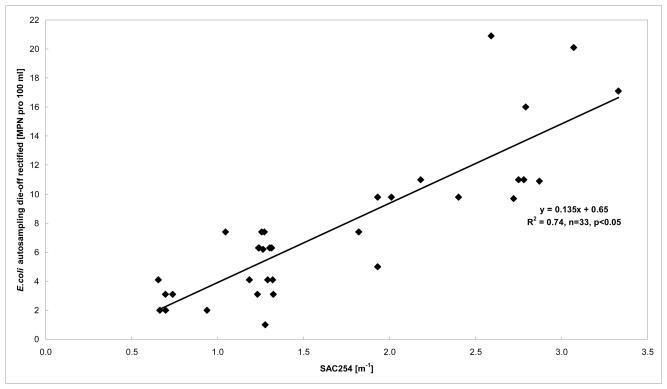

In the past high resolution event monitoring at springs has been based on traditional chemo physical and chemical parameters (e.g. electrical conductivity, turbidity, spectral absorption coefficients, isotopes). Applying the automatic sampling approach together with E.coli field enumeration demonstrates that microbiological investigations with appropriate temporal resolution at remote and hardly accessible alpine areas has now become a realistic goal. Gathered data from summer events 2005/2006 at LKAS2 impressively demonstrate that rapid and significant microbial quality deterioration can happen within a very short period of time highlighting the beneficial effects of spring abstraction management. Application of the proposed approach at karstic spring systems allows for a comprehensive microbial system assessment (WHO, 2004) in order to evaluate their system and type specific behaviour in respect to microbial load and cell transfer under representative and relevant situations (worst case summer events, snow melt events, etc.). For the user, especially with water supply from karst areas, this means, that in combination with on-line turbidity measurements, they have a feasible package for drinking water monitoring at hand. In addition, microbial time series of appropriate resolution become amenable for statistical comparisons to on-line hydrological parameter (e.g. discharge, SAC254, turbidity). For example, correlating the isochronal values of in situ measured SAC254 values and the die-off corrected counts of E.coli from the investigated event 2005/2006 at the LKAS2 indicated distinct correlation clusters, which corresponded to different hydrological phases (data not shown). For the assistance of decision support systems (DSS) of drinking water monitoring systems, the first phase of hydrological events, where the pollution begins, are important. The correlation of these phases of events 2005/2006 is shown in Figure 8. A coefficient of determination of 0.74 (n = 33) was found, indicating that the in-situ measurement of SAC254 is a potential surrogate parameter for “real time” monitoring of recent faecal pollution influence from surface runoff.

Figure 8.

Correlation analysis of SAC254 vs. E.coli MPN autosampling (rectified by die-off rate) for first event phases 2005 und 2006.

Future developments of the technical performance concern mainly the communication and the sampling devices. Three LEO-systems are currently commercially in operation: ORBCOMM (Orbcomm 2007), IRIDIUM (Iridium 2007) and GLOBALSTAR (Globalstar 2007). Their system parameters were compared extensively in a study within the R&D-project “Waterpool” (Waterpool 2005). As Iridium and Globalstar also allow bulky traffic, they can be also used for transmitting pictures from the measuring site. This can be helpful to interpret different effects during flood-events.

The incremental sampling for E.coli by conventional hand sampling procedures compared well to auto-sampling procedures using conventional sampling technology as used for chemical analysis. This confirms a previous report that microbiological cross contamination or carry over for faecal indicators (FI) from corresponding previous sampling cycles are expected below 2%, if dead zones are removed and flushing cycles before each sampling interval are to be applied (Roser et al. 2002). However, the automated microbial sampling could be improved by cooled sampling devices, although the surrounding temperature in the spring tapping of our monitored springs was not appreciable higher as the water temperature (approximately 5.5°C) during summertime. Additionally, the described system is not limited to E.coli as a general parameter of recent faecal pollution and may thus be extended to other appropriate microbial indicators and tracers. In this case, modification may be necessary in order to increase and adapt required sampling storage volumes (Roser et al. 2002).

Acknowledgement

The work was supported by the Vienna Waterworks and by the FWF project P18247-B06 granted to AHF. Our thanks goes to Hermann Kain and Andreas Spanring for excellent technical assistance.

References

- Bonde GJ. Bacteriological indicators of water pollution. Teknisk Verlag; Copenhagen: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Farnleitner AH, Mach RL. Back to the roots”-incidence and abundance of faecal indicators in faeces and sewage of potential pollution sources in an alpine karstic catchment area. 13th Int. Symp. Health Related Microbiol. / Internat. Water Association; Swansea, Wales: 2005a. [Google Scholar]

- Farnleitner AH, Wilhartitz I, et al. Bacterial dynamics in spring water of alpine karst aquifers indicates the presence of stable autochthonous microbial endokarst communities. Environmental Microbiology. 2005b;7:1248–1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CM, Coote BG, Ashbolt NJ, Stevenson IM. Relationship between indicators, pathogens and water quality in a estuarine system. Wat. Res. 1996;30:2045–2054. [Google Scholar]

- Geldreich EE. Indicators of viruses in water and food. Ann Arbor Science Publishing Inc; Ann Arbor: 1978. Bacterial populations and indicator concepts in feces, sewage, stormwater and solid wastes; pp. 51–97. [Google Scholar]

- Globalstrar 2007. http://www.globalstar.com, last visited Jan. 2007.

- International Organisation of Standardisation Water Quality - Detection and enumeration of Escherichia coli and coliform bacteria - Part1: Membrane filtration method. 2000 ISO 9308-1:2000. [Google Scholar]

- Iridium 2007. http://www.iridium.com, last visited Jan. 2007.

- Kay D, Edwards AC, Ferrier RC, Francis C, Kay C, Rushby L, Watkins J, McDonal AT, Wyer M, Crowther J, Wikinson J. Catchment microbial dynamics: the emergence of a research agenda. Prog. Physic. Geogr. 2007;31:59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kralik M. Strategies for the protection of karst aquifers in Austria (in German) Austrian Environmental Protection Agency; Vienna, Austria: 2001. BE-189. [Google Scholar]

- Niemela SI, Lee JV, Fricker CR. A comparison of the International Standards Organisation reference method for the detection of coliforms and Escherichia coli in water with a defined substrate procedure. J Appl Microbiol. 2003;95:1285–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orbcomm 2007. http://www.orbcomm.com and http://www.orbcomm.de, last visited Aug. 2007.

- Roser D, Skinner J, LeMaitre C, Marshall L, Baldwin J, Billington K, Kotz S, Clarkson K, Ashbolt N. Automated event sampling for microbiological and related analytes in remote sites: a comprehensive system. Wat Sci Technol. 2002;2(3):123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Stadler H, Skritek P. Remote Water Quality Monitoring “on-line” using LEO Satellites; Proc. Int. Conf. on Automation in Water Quality Monitoring, 2001; Vienna. 2001. pp. 155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler H, Skritek P. Networking of Automated Event-Sampling Hydro-Meteorological Measuring Sites using LEO-Satellite Communication; Proc. 18th Int. Conf. EnviroInfo2004; Geneva. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Skritek P, Lukasch F, Din K, Hodi T, Stadler H. Environmental Data-Transmission using Low Earth Orbit Satellites; Proc. 16th Int. Conf. EnviroInfo2002; Vienna. 2002. pp. 727–734. [Google Scholar]

- Skritek P, Pfliegl R. Near Online Vessel Tracking on European Waterways combining GPS and LEO-Satellite Transmission; Proceedings of ENC-GNSS2002 Conf. (CD-ROM); Amsterdam. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Waterpool Network of Competence “K-net Wasser”. 2005. http://www.waterpool.org.

- WHO . Guidelines for drinking water quality. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland; 2004. [Google Scholar]