Abstract

Objective

Recent studies suggest that parents maintain influence as their adolescents transition into college. Advances in communication technology make frequent communication between parents and college students easy and affordable. This study examines the protective effect of parent-college student communication on student drinking behaviors, estimated peak blood alcohol concentration (eBAC), and serious negative consequences of drinking.

Participants

Participants were 746 first-year, first-time, full-time students at a large university in the U.S.

Methods

Participants completed a baseline and 14 daily web-based surveys.

Results

The amount of time spent communicating with parents on weekend days predicted the number of drinks consumed, heavy drinking, and peak eBAC consistent with a protective within-person effect. No association between communication and serious negative consequences was observed.

Conclusions

Encouraging parents to communicate with their college students, particularly on weekend days, could be a relatively simple, easily implemented protective process to reduce dangerous drinking behaviors.

Keywords: college health, heavy drinking, parents

Universities are concerned about the academic success and health of their students and demonstrate this concern through policies and programs aimed at reducing risk. Reducing heavy drinking is often the target of such policies and programs because this behavior puts students at risk for difficulties in transitioning to college and for health problems.1–3 In fact, the risk for immediate alcohol-related problems may be greater for young adults enrolled in college than their non-enrolled peers.4 Young adults aged 18 to 22 enrolled full time in college are more likely to use alcohol and engage in binge drinking, defined as consuming five/four or more drinks on the same occasion for men/women, respectively, on at least one day in the past 30 days.5 In 2005, 45% of full time college students engaged in binge drinking in the past 30 days.6 From 1999 to 2005 the proportion of college students who engaged in binge drinking increased significantly.6

College students who engage in heavy drinking experience academic problems through both direct and indirect effects. For instance after controlling for SAT scores, students who consume large amounts of alcohol are more likely to have lower grade point averages (direct association), but also are more likely to experience sleepiness during the day (indirect contributing factor to lower grade point averages).7 In addition, the residual effects from heavy drinking impair students’ visuospatial abilities, motor function, and attention, increasing the risk for poor performance on academic work that requires higher order cognitive skills (e.g., essay writing).8

Other serious problems also have been linked to alcohol consumption among college students. In 2005, more than half a million college students sustained alcohol-related injuries and 1,825 of these students died from their injuries.6 Injuries are directly and linearly associated with the number of alcoholic drinks students consume. Data from the College Alcohol Study, for example, indicate that 18% of students who reported 5 drinks as the usual number of drinks on a drinking occasion during the past 30 days experienced at least one alcohol-related injury in the past school year. The percentage increases to 30% for students who reported 8 or more drinks as the usual number of drinks on a drinking occasion.9 College students’ alcohol consumption also has been associated with other problems such as indiscriminant sexual behaviors,10, 11 unplanned sexual activity, 12 and property damage.13

Students’ alcohol consumption patterns vary with specific events (e.g., spring break), seasons, and days of the week.14,15 Specifically, the prevalence of drinking and of engaging in heavy drinking increases on weekend days.16 Therefore weekend days (defined as Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays) can be considered a period of elevated risk for heavy drinking.

Because drinking is prevalent on college campuses and is associated with poor academic outcomes, injury, and other problems, it is important to identify the factors that protect college students, even in the presence of risk. Protective factors attenuate the effects of risk.17 These processes or characteristics reduce the likelihood of engaging in a problematic behavior (e.g., heavy drinking), even when risk is elevated (e.g., opportunities to drink on weekends).

To more fully understand youth development (and thus possible protective factors) within the college experience, it may be useful to understand the influence of significant others such as parents. Understanding adolescent and young adult development within the context of the parent-adolescent relationship continues to be an important area of study.18 Certain parenting processes and characteristics are well established protective factors for alcohol use during early and middle adolescence. For instance, adolescents whose parents communicate warmth and affection, set and reinforce consistent expectations for behavior, monitor where and with whom the adolescent is, and support adolescents as they develop social skills and competencies tend to initiate alcohol use at later ages and engage in less problematic drinking patterns.19–23 Also, a substantial body of literature underscores the importance of parental involvement in reducing substance use, even among college students.24,25

While these empirically supported protective parenting characteristics are clearly important, they become more difficult for parents to implement as their children transition to college. For instance, monitoring has been defined as, “attention to and tracking of the child’s whereabouts, activities and adaptations”.26 Parents may find it more difficult to directly track where their college students are and with whom, particularly when the students live independently. Moreover, establishing autonomous lives and healthy lifestyles is a normative developmental task for students, thus it could be developmentally inappropriate for parents to monitor to the extent that is beneficial earlier in life.27 At the same time, parent-college student communication may be as important as direct monitoring or tracking because voluntary disclosure of activities by the student is associated with fewer problem outcomes.28, 29 Similarly, regular communication of warmth, expectations, and encouragement is feasible and may continue to play an important protective role as students and their parents evolve toward establishing adult relationships.

Parent-student communication and parental support exert influence in other domains of college students’ (or soon-to-be college students’) lives. For instance, high school seniors consult parents significantly more often than they do peers, other adults, teachers, information from colleges, or the media regarding decisions about where to apply to and/or attend college.30.31 While attending college, students turn to their parents for help during times of stress and report that they value the assistance they receive.32–35 Contact between college students and their families is frequent. Forty percent of first year college students report daily interactions with their family, a higher percentage than interact daily with close friends not attending their university.35 Recent advances in communication technology, including lower prices for mobile phones and service, computers, and Internet access make frequent communication between parents and college students easy and affordable. While these technologies can be used for a variety of purposes, mobile phones in particular are used to communicate with people who have “strong ties” to the user.36 In one study of college student mobile phone use, students reported that they use their mobile phone for direct contact with their mothers and fathers.36 Specifically, participants used mobile phones to ask for help, to receive emotional and physical support and to share experiences with parents.37 In addition to advances in the enabling technology, changing societal expectations and norms regarding the frequency and nature of parent-student contact may contribute to increased communication. Given the importance of parent-student relationships during the transition to college where opportunities for high risk drinking behaviors increase, we sought to examine whether students drank as much or experienced as many negative drinking consequences on weekend days when they communicated with their parents as on weekend days when they did not. We also wanted to explore if the protective effect of communicating with parents was stronger for students who spent more time on a given day communicating.

This paper examines the protective effects of parent-college student communication on drinking behaviors, estimated peak blood alcohol concentration (eBAC), and self-reported serious negative consequences of drinking. Specifically, we tested whether, on higher risk drinking days (Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays), greater communication with parents predicted drinking fewer drinks, a lower likelihood of engaging in heavy alcohol consumption, lower eBAC, and fewer serious negative consequences.

METHODS

Data used in the current analyses were drawn from the University Life Study (ULS), a longitudinal study of daily life experiences among college students. The ULS used a measurement burst design, with a baseline survey followed by 14 consecutive daily surveys each semester. Eligible participants were first-year, first-time, full-time students at a large university in the Northeastern U.S. A stratified random sampling procedure was used to achieve a diverse sample of students with respect to sex and race/ethnicity. The ULS sample was not designed to be representative of the university’s overall student population which includes a higher proportion of white than racial or ethnic minority students.

During the first week of fall classes, recruitment letters were sent to selected students with a pen and $5 enclosed. Email invitations followed, with secure links to the surveys administered via the world wide web. Students were invited to complete a baseline survey and then 14 consecutive daily surveys. Incentives for participation were the $5 pre-incentive, a $20 baseline survey incentive, and $3 per daily survey incentive with an $8 completion bonus (maximum $75 total for all surveys). Participants provided an electronic signature on an online consent form. The study was approved by the institution’s Institutional Review Board and was protected by a federal Certificate of Confidentiality. In total, 746 students (65.6% response rate) completed the baseline survey. The final sample self-identified as 25% Hispanic/Latino American. The sample was racially diverse. Among non-Hispanic/Latino Americans, 16% of the sample self-identified as African American, 23% as Asian American/Pacific Islander American, 27% as European American, and 9% as more than one race. Almost all (98.1%) lived in on-campus residence halls. Completion rates of the daily surveys were high, with most (86%) of the participants completing at least 12 of the 14 daily surveys, giving a total of 9,482 days of daily data in Semester 1.

Daily Communication with Parents

Each day, participants were asked, “From the time you woke up until you went to sleep, how much time did you spend doing the following activities?” “Talking to/emailing/messaging with parent(s)” was one of 19 daily activities for which students were asked to provide time estimates, with possible responses of “did not do,” “did do for up to 30 minutes,” “did do for 30 minutes to 60 minutes,” “did do for one hour,” and then increasing by hour increments to 10+ hours. The amount of time communicating with parents, was recoded into three categories: (0) no time; (0.5) less than 30 minutes; and (1) 30 minutes or more.

Daily Quantity of Alcohol Use

The quantity of alcohol consumed on each day was assessed with the question, “How many drinks of alcohol did you drink?” Participants were instructed to answer for the previous day, for example, “This survey is about Friday [yesterday] from the time you woke up until you went to sleep.” One drink was defined as, “half an ounce of absolute alcohol, one 12 ounce can or bottle of beer or cooler, one 5 ounce glass of wine, or a drink containing 1 shot of liquor or spirits”.38 The number of standard drinks participants reported consuming each day was used to compute three outcome variables. First, the total number of drinks was used as a continuous variable (range = 0 to 25 drinks). Second, heavy alcohol consumption was coded as a dichotomous variable (no=0, yes=1) and was defined as men consuming five or more drinks and women consuming four or more drinks.5

Time Spent Drinking

The amount of time respondents spent drinking was assessed with two questions, “What time did you start your first drink,” and “What time did you finish your last drink.” Respondents entered the hour, minute and a.m. or p.m. for each question. The total time spent drinking was calculated as the difference between these two variables.

For students who reported consuming at least one drink, estimated peak blood alcohol concentration (eBAC) was calculated using Matthew and Miller’s39 (1979) formula, which represents an event-level index of intoxication, based on the number of standard drinks consumed, time spent drinking, sex, weight, and the average alcohol metabolism rate* . Hustad and Carey40 evaluated the accuracy of retrospective eBACs among college student bar patrons by comparing five methods of calculating eBAC to in vivo blood alcohol concentrations obtained through breath tests (BrAC). While the five methods were highly inter-correlated (r ≥ .99), and also very strongly correlated with BrAC (r ≥ .73), the Matthews and Miller eBAC equation had a higher rate of agreement with BrAC. However, eBAC formulae tend to overestimate BrAC when more drinks are consumed, the drinking episode is longer, education is higher, and drinkers are men or have greater weight. Despite these limitations, eBAC provides unique data beyond standard self-reports of frequency and quantity, and are a satisfactory estimate of actual intoxication.40

Serious Daily Consequences of Drinking

Serious daily consequences of drinking were assessed with a yes/no response to each of the following, “As a result of drinking on Friday [yesterday] did you: Lose control of yourself; Pass out; Get in trouble with the police or university authorities for drinking; Find yourself in a situation where no one was sober enough to drive; Not get your schoolwork done.” While not as immediately serious as the others, failure to complete schoolwork was included as this is a primary responsibility for students and is a contributing factor to dropping out of college.

The survey tool was developed through a series of systematic steps. Measures were obtained and adapted from other large-scale surveys of college students. An extensive pilot test was conducted in the semester preceding data collection in which over 200 first-year students completed the web-based surveys including the daily assessments. The validity of these pilot data for assessing alcohol use and sexual behavior has been documented in a separate publication 41.

RESULTS

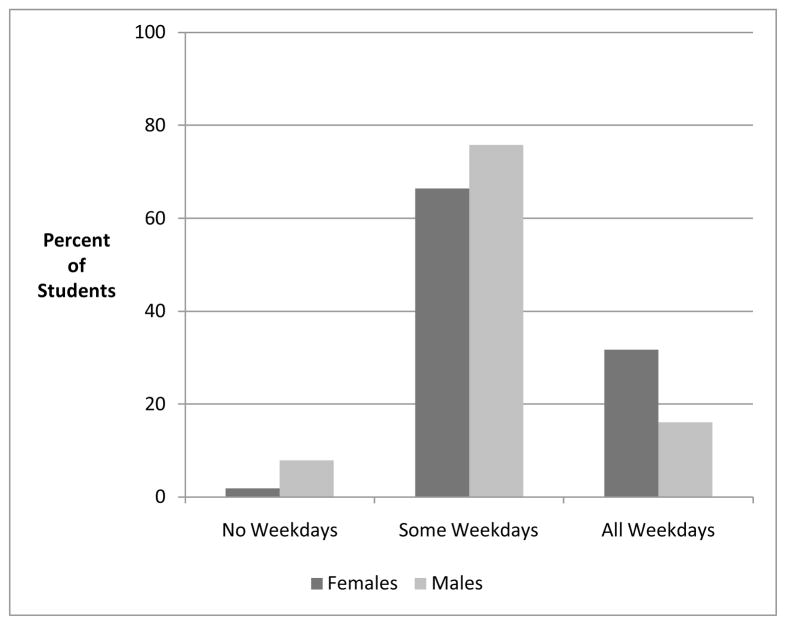

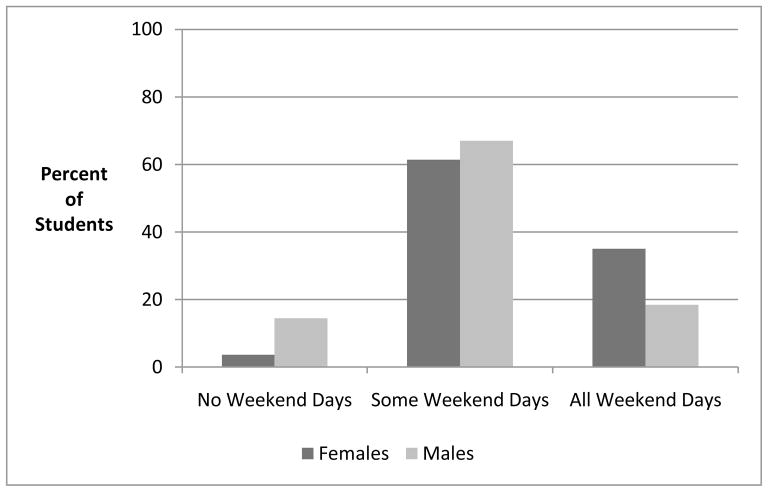

The prevalence of parent-student communication was high, and patterns of communication were similar for week days and for weekend days. Most students (95%) communicated with their parents on at least one of the 8 week days (Sunday through Wednesday) surveyed and many communicated with their parents on more than one week day (Figure 1). Female students communicated with their parents on more weekdays than did male students (Figure 1). Similarly, most students (91%) communicated with their parents on at least one of the six weekend days surveyed, and many communicated on more than one of the six weekend days (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Percentage of Students Who Communicated with Their Parents on the Eight Weekdays Surveyed by Days and Sex

Figure 2.

Percentage of Students Who Communicated with Their Parents on the Six Weekend Days Surveyed by Days and Sex

Because alcohol prevalence is highest on Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays,16 the relative risk of heavy drinking and negative consequences is greatest on these days. The current analyses used data from the six weekend days of the study. A total of 4,019 daily surveys were used in the analyses.

More than half (55%) of the students had at least one drink on one sampled weekend day, and 35% reported heavy drinking on at least one day. On weekend days when students reported at least one drink, the average number of drinks consumed was 5.45 (SD = 3.19). On weekend days when students consumed alcohol, the average eBAC was .11 (SD=.07). More than half (64%) did not report experiencing any of the five serious negative consequences measured as a result of their drinking across the sampled weekend days; 22% reported one serious consequence; and 13% reported two or more serious consequences.

Four models, estimated with HLM 6.04,42,43 were used to predict total number of drinks, heavy drinking, eBAC, and negative consequences. Due to skew in the total number of drinks variable, including a large number of zeroes (i.e., days with no alcohol consumed), a Poisson distribution was used.44 For the dichotomous outcomes of heavy drinking and serious negative consequences, a Bernoulli distribution was used.42 The eBAC variable was normally distributed so a linear model was used. eBAC was only calculated for respondents who reported at least one drink. To account for typical levels of communication and thus to isolate the within-person association of communication on a given weekend day with alcohol use, individual means of the amount of time students spent communicating with their parents across the 14 days were entered into the model. This allowed us to isolate any protective effect of communicating with parents specifically on weekend days. Across the 14 days of data collection, female students communicated with their parents on more days than did male students, therefore sex was entered as a control variable.

Multi-level models nesting days within persons showed that the amount of time spent communicating with parents on weekend days predicted the number of drinks consumed, consistent with a protective within-person effect. Compared to days when students did not communicate with their parents, on days when students communicated for more than 30 minutes, they consumed 20% fewer drinks (Table 1). An even stronger effect was found for heavy drinking. Compared to days when students did not communicate with their parents, on days when students communicated for more than 30 minutes, they were 32% less likely to engage in heavy drinking (Table 1). A protective effect for eBAC also was observed. Compared to days when students did not communicate with their parents, on days when they communicated for more than 30 minutes, they had a .02 reduction in eBAC (Table 1). All 50 states and the District of Columbia have per se laws defining it as a crime to drive with a peak BAC at or above 0.08 percent, so a .02 reduction is meaningful. No effect of communicating with parents was observed for self-reported serious negative consequences, perhaps due to relatively low prevalence of the assessed consequences despite heavy drinking.

Table 1.

Parent Communication Predicting Number of Drinks, Excessive Drinking, and Serious Negative Consequences, and Estimated Peak Blood Alcohol Concentration

| Fixed Effects | Number of Drinks Event Rate Ratio | Excessive Drinking OR [CI] | Serious Negative Consequences OR [CI] | Estimated Peak BAC Coefficient (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Outcome over 14 days | ||||

| Intercept, | 0.61 [0.43, 0.87]** | 0.13 [0.09, 0.19]** | 0.43 [0.27, 0.71]** | 0.13 (.01)** |

| Male | 1.28 [0.97, 1.69] | 1.12 [0.83, 1.53] | 0.82 [0.54, 1.23] | −0.02 (.01)* |

| Average Parent Communications | 0.95 [0.52, 1.73] | 1.33 [0.67, 2.67] | 0.56 [0.21, 1.46] | −0.00 (.01) |

| Average Fluctuations in Daily Parent Communications | ||||

| Intercept | 0.80 [0.65, 0.98]* | 0.68 [0.51, 0.92]* | 0.68 [0.39, 1.19] | −0.02 (.01)* |

p<.05

p<.001

Most of the students were in the university town on the weekend days when they were surveyed (91% of the weekend days). However, because a third variable such as being at home with parents could confound the association between communicating with parents and drinking, location (e.g., in the university town or elsewhere) was entered as a control variable in supplemental analyses. After controlling for location, a statistically significant effect for number of drinks (20% reduction) and heavy drinking (25% reduction) remained. The coefficient for eBAC was not statistically significant, possibly due to a reduction in power. As with the original analyses, no effect was found for self-reported serious negative consequences of drinking.

COMMENT

The level and type of parent involvement with universities has received recent attention in the popular press. Parents have been characterized as overly involved and overly influential by college administrators. However, many universities are exploring ways to productively engage parents, particularly around the areas of health promotion and risk reduction. Our study supports the value of these efforts by demonstrating that parents and students communicate often and that increased parent communication is associated with less drinking among first-year college students.

Our findings extend the work of others who have examined the protective role of parents in younger adolescents. For instance, Tobler and Komro found that high levels of consistent parental monitoring and communication were associated with lower levels of drug and alcohol use in middle school students19. Our findings suggest that the benefits of high levels of communication extend into the first year of college.

There are a number of possible ways that parent communication could influence college students’ drinking. First, there could be a direct effect such that when parents express their concern about excessive drinking or suggest strategies for reducing harm the students consume less alcohol. There also could be an indirect effect whereby interaction with parents may remind the student of shared values, internalized norms, or the importance of longer-term goals (reflecting a more generalized parent socialization or relationship effect.). Taken together, these possible mechanisms could be used to develop parent materials that could be incorporated into freshman orientation programs or online alcohol education interventions (e.g., AlcoholEdu and e-Chug) . Hustad, et al found that online alcohol prevention programs are a promising approach for reducing college student drinking45. Parent modules could be developed and offered in conjunction with these universal alcohol programs. Parents could complete these modules online or during an orientation visit. Behavioral triggers also could be integrated. For instance, parents could be sent automated text reminders to contact their students, particularly on higher risk drinking days. Similarly, social marketing campaigns could be implemented on campus to encourage students and/or parents to stay in regular contact.

Future research should test the impact of programs designed to increase both the direct and indirect effects of parent-college student communication. Future research also should examine changes in the quantity, quality, and content of communication, and the potential protective effects, as students progress through college. It is likely that the parent-student communication association is most salient during the first semester or first year of college, so the timing of programs and information to parents should coincide with this important transition period. Investments in this critical period may prove to be particularly effective because reducing dangerous drinking during the first semester of college could change the trajectory of students’ risk behaviors throughout their college experience and therefore present an ideal window for a preventive intervention.

LIMITATIONS

The current analyses have several limitations. No mediators or moderators were measured. This limits our ability to explain the mechanisms by which parent-student communication might influence drinking behaviors or to identify subgroups of students for whom the findings might be particularly salient. For instance the quality of the student-parent relationship or expectations for alcohol use also could explain the effects whereby students with high quality parent relationships and/or parents who do not tolerate underage alcohol use consume less alcohol on days when they communicate with their parents. Communication with mothers and fathers was not assessed separately but could impact student alcohol use differentially. Although the within-person design controls for stable shared third-variable causes, such as students who feel close to their parents drinking less overall, reverse within-person causality is possible though unlikely. For example, students who decide not to drink on a given day may have more time to call their parents. Finally, the sampling methodology and high response rates produced a racially and ethnically diverse sample. However, due to the strategic over-recruitment of ethnic minority students the sample is not representative of the overall student population which limits our ability to generalize the findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Encouraging parents to communicate with students while at college, particularly on weekend days when the environmental risk for heavy drinking is high could be a relatively simple, easily implemented protective intervention to reduce dangerous drinking. Current e-interventions could be modified to include a parent component and may offer universities a cost effective strategy to apply the findings of this research.

Acknowledgments

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism supported the University Life Study with a grant to J. Maggs (R01 AA016016). The content here is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsor.

Footnotes

The Matthews & Miller's39 (1979) formula uses three variables (c = number of standard drinks consumed, w= person’s weight, t= time spent drinking), a gender constant (GC = gender constant [9.0 for females and 7.5 for males], and an average per hour alcohol metabolism rate (β60 =0.017 g/dl). eBAC = [(c/2) * (GC/w)] − (β60*t)

References

- 1.Wechsler H, Seibring M, Liu IC, Ahl M. Colleges respond to student binge drinking: Reducing student demand or limiting access. Journal of American College Health. 2004;(52):159–168. doi: 10.3200/JACH.52.4.159-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Long SW, et al. The problem of college drinking: Insights from a developmental perspective. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25(3):473–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL, O'Malley PM. How and why the understanding of developmental continuity and discontinuity is important: The sample case of long-term consequences of adolescent substance abuse. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ, editors. Handbook of the Life Course. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drug Use. 2002;(suppl 14):23–29. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of Applied Studies. Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hingson RH, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drug Use. 2009;(suppl16):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singleton RA, Wolfson AR. Alcohol consumption, sleep, and academic performance among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drug Use. 2009;69(3):355–363. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howland J, Rohsenow DJ, Greece JA, Littlefield CA, Almeida A, Heeren T, Winter M, Bliss CA, Hunt S, Hermos J. The effects of binge drinking on college students’ next-day academic test-taking performance and mood state. Addiction. 2010;(105):655–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wechsler H, Nelson TF. What we have learned from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study: Focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drug Use. 2008;69(4):481–490. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper LM. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(suppl 14):101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein AL, Barnett NP, Pedlow CT, Murphy JG. Drinking in conjunction with sexual experiences among at-risk college student drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drug Use. 2007;68(5):697–705. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perkins WH. Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(suppl 14):91–100. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham CC. Anger and alcohol use: A dangerous combination. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2003;(63):4369. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CM, Maggs JL, Rankin LA. Spring break trips as a risk factor for heavy alcohol use among first-year college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;(67):911–916. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. National Institutes of Health. 2006. Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use. Overview of key findings, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Up close and personal: Temporal variability in the drinking college students during their first year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(2):155–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;147(6):598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins A, Laurensen B. Changing relationships, changing youth: Interpersonal contexts of adolescent development. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2004;24(1):55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tobler AL, Komro KA. Trajectories of parental monitoring and communication and effects on drug use among urban young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;(46):560–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;(112):64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White HR, Johnson V, Buyske S. Parental modeling and parenting behavior effects on offspring alcohol and cigarette use: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;12(3):287–310. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patcock-Peckham JA, Morgan-Lopez AA. College drinking behaviors: Mediational links between parenting styles, parental bonds, depression, and alcohol problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(3):297–306. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abar C, Turrisi R. How important are parents during the college years? A longitudinal perspective of indirect influences parents yield on their college teens' alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(10):1360–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abar C, Abar B, Turrisi R. The impact of parental modeling and permissibility on alcohol use and experienced negative drinking consequences in college. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(6–7):542–547. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood MD, Mitchell RE, Read JP, Brand NH. Do parents still matter? Parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(1):19–30. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical foundation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1(1):61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutman LM, Eccles JS. Stage-environment fit during adolescence: Trajectories of family relations and adolescent outcomes. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(2):522–537. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: a reinterpretation. Child Development. 2000;71(4):1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Padilla-Walker LM, Nelson LJ, Madsen SD, McNamara BC. The role of perceived parental knowledge on emerging adults’ risk behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37(7):847–859. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galotti KM, Mark MC. How do high school students structure an important life decision? A short-term longitudinal study of the college decision-making process. Research in Higher Education. 1994;35(5):589–607. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toor R. Pushy parents and other tales of the admissions game. Chronicle of Higher Education. 2000;47(6):B18. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kenny ME. The extent and function of parental attachment among first-year college students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16(1):17–29. doi: 10.1007/BF02141544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birch DA, O'Toole TP, Kanu AJ. Health discussions between college students and parents: Results of a Delphi study. Journal of American College Health. 1997;46(3):139–143. doi: 10.1080/07448489709595600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyd VS, Hunt PF, Hunt SM, Magoon TM, Van Brunt JE. Parents as referral agents for their first year college students: A retention intervention. Journal of College Student Development. 1997;38:191–193. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu A, Sharkness J, Pryor JH. Findings from the 2007 administration of 'Your First College Year' (YFCY) Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Gournay C. Pretense of intimacy in France. In: Katz JE, Aakhus M, editors. Perpetual Contact: Mobile Communication, Private Talk, Public Performance. Cambridge: University Press; 2002. pp. 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen YF, Kat JE. Extending family to school life: College students’ use of the mobile phone. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 2009;67(2):179–191. [Google Scholar]

- 38.International Center for Alcohol Policies (ICAP) What Is A Standard Drink? Washington, DC: International Center for Alcohol Policies; 1998. ICAP Reports No.5. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matthews DB, Miller WR. Estimating blood alcohol concentration: Two computer programs and their applications in therapy and research. Addictive Behaviors. 1979;(5):55–60. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hustad JTP, Carey KB. Using calculations to estimate blood alcohol concentrations for naturally occurring drinking episodes: A validity study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;(66):130–138. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patrick ME, Maggs JL. Does drinking lead to sex? Daily alcohol-sex behaviors and expectancies among college students. Journal of Addictive Behaivors. 2009;23(3):472–481. doi: 10.1037/a0016097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon R. HLM: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling [Computer software]. Version 5. Chicago: Scientific Software International; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Snijders TA, Bosker RJ. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. London etc: Sage Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hustad JTP, Barnett NP, Borsari B, Jackson KM. Web-based alcohol prevention for incoming college students: A randomized controlled trial. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(3):183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]