Abstract

Little longitudinal research has been conducted on changes in children's emotional self-regulation strategy (SRS) use after infancy, particularly for children at risk. The current study examined changes in boys' emotional SRS from toddlerhood through preschool. Repeated observational assessments using delay of gratification tasks at ages 2, 3, and 4 were examined with both variable- and person-oriented analyses in a low-income sample of boys (N = 117) at-risk for early problem behavior. Results were consistent with theory on emotional SRS development in young children. Children initially used more emotion-focused SRS (e.g., comfort seeking) and transitioned to greater use of planful SRS (e.g., distraction) by age 4. Person-oriented analysis using trajectory analysis found similar patterns from 2–4, with small groups of boys showing delayed movement away from emotion-focused strategies or delay in the onset of regular use of distraction. The results provide a foundation for future research to examine the development of SRS in low-income young children.

Keywords: Emotional self-regulation, early childhood, behavior problems

Emotional self-regulation strategies (SRS) refer to those strategies that an individual may use to self-regulate their emotions. Emotional SRS encompass a variety of deliberate or automatic cognitive and physiological processes. Emotional SRS include predicting and dealing with existing or anticipated stressors by modulating behavior (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997). Kopp's (1989) theory of the development of emotion regulation and other related theoretical accounts (e.g., Blair, 2002; Calkins, 2004; Grolnick, McMenamy, & Kurowski, 1999; Karoly, 1993) suggest pathways for the development of emotional SRS during early childhood. Most of the supporting empirical research, however, has relied on concurrent or cross-sectional data (e.g., Berlin & Cassidy, 2003; Braungart-Rieker & Stifter, 1996; Mangelsdorf, Shapiro, & Marzolf, 1995; Pauli-Pott, Mertesacker, & Beckmann, 2004; Rothbart, Ziaie, & O'Boyle, 1992; Stansbury & Sigman, 2000).

A body of literature suggests that less adaptive use of emotional SRS predicts increased risk for externalizing and internalizing problems (Buckner, Mezzacappa, & Beardslee, 2003; Gilliom, Shaw, Beck, Schonberg, & Lukon, 2002; Silk, Shaw, Forbes, Lane, & Kovacs, 2006; Trentacosta & Shaw, 2009). Without effective regulatory skills, children may choose a less socially appropriate response to their emotions (e.g., aggression) rather than choosing a more appropriate response (Gilliom et al., 2002). Research has consistently found a relationship between children's development of high rates of externalizing behavior and sociodemographic adversity, including low-income, low parental education, and low social resources for parents (e.g., Loeber & Dishion, 1983). Although the environmental stressors associated with growing up in a low-income home have been linked to increased risk for conduct problems and difficulties in emotion regulation, the majority of low-income children do not develop emotional problems (Raver, 2004). However, longitudinal research is needed with low-income, at-risk children to begin to understand these individual differences, which may be linked to individual differences in the development of emotional SRS usage.

Relationship Between Emotional SRS and Child Outcomes

Children's use of specific emotional SRS (e.g., seeking comfort from a caregiver) is associated with children's behavioral outcomes at school (Blair, Denham, Kochanoff, & Whipple, 2004; Eisenberg, Fabes, Nyman, Bernzweig, & Pinuelas, 1994; Gilliom et al., 2002; Miller, et al., 2006) and at home (Feldman & Klein, 2003; Stansbury & Zimmerman, 1999), both concurrently and longitudinally (e.g. Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Terranova, & Kithakye, 2010). Children found to be adept at shifting their focus in an emotional situation have been found to be not only less likely to show increases in negative affect during the situation, but also less likely to exhibit subsequent externalizing behavior and more likely to be cooperative in school (Eisenberg et al., 1996; Gilliom et al., 2002).

The associations between early emotional SRS and social, behavioral, and cognitive outcomes suggest a need for research on individual differences in emotional SRS development across toddlerhood and the preschool period. Although examination of individual differences at a single time point informs the understanding of SRS for potential targets for treatment, examining individual differences in emotional SRS over time can help to uncover non-normative trajectories that may lead to later problems and inform efforts to prevent maladaptive behavioral outcomes. For example, at-risk children may not use effective SRS, such as active distraction, at the same age or at the same rate as children who are not at-risk. This delay in using effective SRS may be problematic as the social and behavioral demands increase in the preschool and early school environment. Exploration of patterns of SRS use over time (i.e., person-oriented analyses) could identify potentially troublesome developmental paths and possible prevention or intervention points.

Theory of Emotional SRS Development

The achievement of rudimentary emotional self-regulation skills begins very early in life (Grolnick et al., 1999; Kopp, 1989), but these skills continue to develop throughout the early school years (Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Posner & Rothbart, 2000), changing rapidly during the toddler and preschool periods (Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Vaughn, Kopp, & Krakow, 1984). The individual's unique experiences during the process of developing emotional SRS is hypothesized to contribute to individual differences in children's ability to utilize different SRS effectively, leading to individual differences in behavioral control (Calkins & Howse, 2004).

In the initial months of infancy, children primarily use reflexive SRS (e.g., head turning) to alleviate distress (Field, 1981; Grolnick et al., 1999; Kopp, 1989; Toda & Fogel, 1993). By about the third month, children move toward more varied forms, some of which appear to be more active attempts at self-soothing and social communication (e.g., crying brings a caregiver to soothe the infant; Kopp, 1989). The theory that children move toward strategies that involve social communication directed at caregivers has received some empirical support (Grolnick, Bridges & Connell, 1996; Mangelsdorf, et al.,1995; Rothbart, et al., 1992). Eventually infants decrease some of their dependence on the caregiver and begin to engage in basic forms of active self-regulation when they encounter distressing situations (Kopp, 1989).

As children move from late infancy to the toddler period, they become more planful and organized rather than reflexive in their self-regulation and begin to be able to distract themselves from the source of distress (Rothbart, Posner, & Kieras, 2006). Children's active attempts to change the source of their negative emotions increase from 18 to 24 months of age (Van Lieshout, 1975). From toddlerhood through the preschool years, children continue to develop more sophisticated regulation strategies in conjunction with their burgeoning advances in cognitive and language skills, understanding of cause and effect relationships, and increased self-awareness (Calkins & Howse, 2004; Dodge, 1989; Grolnick et al., 1999; Kochanska, Murray, & Coy, 1997; Kopp, 1989; Thompson, 1990).

According to theory, during the second and third years children begin to understand how certain situations tend to arouse specific emotions and can therefore organize and monitor their behavior more effectively to obtain control over their emotional expression in these situations (Calkins, 2004; Calkins & Howse, 2004). Preschool children's increasing proficiency with the use of SRS such as active distraction is associated with behaviors such as playing with enjoyable toys that improve (or ignore) a distressing situation (Denham, 1998). Kopp (1989) hypothesized by the end of the preschool period children have developed new and increasingly complex ways of regulating their emotions that are more planful and organized, a supposition corroborated by multiple research groups (Diener & Mangelsdorf, 1999; Mendez, Fantuzzo, & Cicchetti, 2002). However, both Kopp (1989) and Cole, Michel, and Teti (1994) noted that when children become over-aroused or lack the coping ability for a specific situation, they may regress to formerly used, less developmentally sophisticated strategies or become unable to effectively utilize SRS to calm themselves.

Emotional Self-regulation Behaviors

Previous research has used a variety of terms to describe observed emotional SRS behaviors. The first series of behaviors are the emotion-focused active behaviors in which children actively cope with their emotion but do not attempt to change the source of distress. Kopp (1989) mentioned such behaviors as emerging in early infancy to modulate distress (e.g., sucking on a finger), which Grolnick et al. (1999) referred to as “comfort behaviors.” These behaviors also include the utilization of a caregiver to deal with the child's emotions.

Another set of behaviors are the emotion-focused passive behaviors in which children appear to suppress their emotional expressions and remove themselves from the situation mentally. For example a child may stare at a wall for 4 s or more, not appearing to focus on anything in particular. These emotion-focused passive behaviors are not independently discussed in theoretical accounts, but previous research indicated that muted emotional expression was uniquely associated with externalizing behavior (Cole, Zahn-Waxler, Fox, Usher, & Welsh, 1996). Research has supported the presence of passive behaviors in response to frustration in infants (Ganiban, Bridges, Supplee, & Brewster, 1998) and preschoolers (Silk et al., 2006).

According to Kopp (1989), the child's use of planful strategies, or observable behaviors that indicate the child's reduction of or ignoring of the distress, is more advanced and emerges along with the development of cognitive skills during the toddler period. Grolnick et al. (1996) referred to these behaviors as “distraction.” Distraction can include the children talking to the caregiver or dancing around the room. Children's use of planful strategies in the preschool years has been related to positive behavioral outcomes in previous research (Gilliom et al., 2002; Trentacosta and Shaw, 2009). For example, children who used a planful strategy of refocusing their attention in preschool or kindergarten had less concurrent expressed anger and significantly fewer externalizing behavior problems as reported by teachers in first or second grade (Morris et al., 2010).

Based on the results of Grolnick et al.'s (1996) work, children who do not use SRS that successfully reduce emotions and instead display strategies that maintain emotional arousal, such as focusing on the point of their distress, later may have higher levels of externalizing behaviors (Gilliom et al., 2002). For example, they may reach for a forbidden object or cry because they cannot obtain a desired object. Previous research has corroborated that children who focus on the point of distress have higher levels of subsequent externalizing behaviors (Gilliom et al., 2002; Morris et al., 2010).

Additional Risk Factors Related to the Development of Emotional SRS and Externalizing Behavior

Some research suggests that the development of emotional SRS due to social factors may differ between boys and girls (Conway, 2005; Eschenbeck, Kohlmann, & Lohaus, 2007; Werner, Cassidy, & Juliano, 2006; Zimmerman & Stansbury, 2003). Research also indicates that boys are more emotionally expressive early in life than girls, and parents' different responses to affect may socialize differential emotional SRS beginning in infancy and early childhood (Brody, 1995; Weinberg, Tronick, Cohn, & Olson, 1999). Therefore examining children's pattern of emotional SRS separately by gender minimizes intergender differences to focus on intragender differences. Overall, empirical research on gender differences in emotional SRS in early childhood has received limited attention, but the majority of research supports a gender difference in rates of conduct problems, with boys beginning to show higher rates than girls around age 4 (Keenan & Shaw, 1997). For researchers to begin to understand the trajectories of SRS development in children at risk for behavioral problems, it may be advantageous to examine these patterns separately by gender as children approach preschool age.

The term at-risk can have very different meanings in different contexts and domains. In the current study, “at-risk” refers to factors related to the development of conduct problems. Previous empirical research has identified variables that appear to be related to the development of early conduct problems in boys including low family socioeconomic status, family risk factors including maternal depression and high parenting stress, and child risk factors including difficult temperament (e.g. Shaw, Lacourse & Nagin, 2005). The current study defined at-risk as children having many, if not all, of the risk factors mentioned above.

The Current Study

The current study is the first known use of variable- and person-oriented statistical approaches to examine emotional SRS longitudinally with a sample of low-income boys at risk for the development of early-starting conduct problems. Variable-oriented analysis examines overarching patterns in the data such as overall trends in the stability and growth of the sample as a whole, but this approach assumes the population is relatively homogenous (Laursen & Hoff, 2006). Person-oriented analysis, on the other hand, assumes the population is heterogeneous and captures groups of individuals within the sample who demonstrate similar patterns on specific variables (Laursen & Hoff). The current study used both of these techniques to address gaps in the literature and inform future theoretical, empirical, and applied innovations related to the development of emotional SRS across the toddler and preschool periods.

A central goal of this study was to identify the longitudinal patterns of SRS development in a sample at risk for the development of behavior problems. The study is noteworthy because it takes the first step towards empirically examining longitudinal trajectories of emotional SRS development for low-income boys at-risk for the development of externalizing behavior problems. Using a variable-oriented approach, the current study examined the mean ratio of boys' use of individual types of SRS longitudinally during the toddler and preschool periods. We hypothesized that as a function of age boys would increasingly use more sophisticated and planful strategies and decreasingly use less sophisticated, more emotion-focused strategies, such as self-soothing. Second, the use of a person-oriented analytic approach allowed us to examine groups of boys who demonstrated homogeneous patterns of strategy use over time. We anticipated that most of the boys would use more active, emotion-changing strategies over time, despite their at-risk status.

Method

Participants

Participants included 117 mother-son dyads recruited from the Women, Infant and Children (WIC) Nutritional Supplement Program in the Pittsburgh, PA metropolitan area during the spring and summer of 2001. Families were approached at WIC sites and invited to participate if they had a son between 17 and 27 months old and they reported having two out of three risk factors: socioeconomic (i.e., met WIC income criteria and less than 2 years post-secondary education), family (i.e., parenting stress, parental depressive symptoms), or child (i.e., difficult temperament or behavioral issues) factors. Because the main study focused on boys' behavioral problems, if the family qualified based only on socioeconomic and family risk factors, the child needed a score above the normed mean on the caregiver's report of the child's behavioral problems to be eligible for participation. Of 271 families who participated in the screening, 124 families met the eligibility requirements and 120 (97%) agreed to participate in the study. Three families were excluded from the current analysis: one family did not participate in the delay of gratification tasks and therefore had no SRS data, and two families had boys identified with developmental disabilities after entering the study. As shown in Table 1, the boys in the sample had a mean age of 24.1 months (range 17.6 to 30.1 months). At the time of assessment, the mean age of mothers was 27.2 years (SD = 6.1), with a range between 18 and 45 years of age and the income in 2001 was $3,624 (range $480 to $13,000) per family member per year. The mean level of education attainment for mothers was 12.23 years (SD = 1.41).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic Description and Screening Criteria of Sample at the Age 2 Home Visit (N=120)

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Child's Age (Months) | 24.10 | 2.80 |

| Maternal Age (Years) | 27.20 | 6.10 |

| Number of People in Home | 4.49 | 1.53 |

| Annual Income | $15,504.92 | 8,754.25 |

| Annual Per Capita Income | $3,624.14 | 2,058.24 |

|

|

||

| N | % | |

|

|

||

| Child's Ethnicity | ||

| African-American | 58 | 48.30 |

| Caucasian | 48 | 40.00 |

| Biracial | 14 | 11.70 |

| Maternal Education | ||

| Less than High School | 22 | 18.30 |

| High School/GED | 58 | 48.30 |

| Greater than High School | 40 | 33.30 |

| Maternal Marital Status | ||

| Married/Living with Partner | 54 | 45.00 |

| Single and Never Married | 60 | 50.00 |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 6 | 5.00 |

| Screening Criteria | ||

| Eyberg Intensity Score | 122.30 | 27.00 |

| Eyberg Problem Score | 12.25 | 6.25 |

| CBCL 2/3 Internalizing Factor (T-scores) | 57.87 | 8.41 |

| CBCL 2/3 Externalizing Factor (T-scores) | 59.95 | 7.58 |

Procedure

The families in the current study were invited to participate in a randomized clinical trial of a treatment focused on the prevention of behavioral problems. Those randomly assigned to the treatment group were offered the opportunity to confer with a parent consultant to discuss family and parenting issues and use the parent consultant as a resource for community services whereas those assigned to the control group only participated in annual assessments. For additional details on the treatment and its impacts, see Shaw, Dishion, Supplee, Gardner, and Arnds (2006).

Mothers and sons completed three home-based assessments, one each when the boys were 2 (M = 23.63 months; SD = 2.8), 3 (M = 35.88 months; SD = 2.7), and 4 (M = 48.33 months; SD = 3.1) years old. Families were reimbursed for their time at each assessment, and all tasks were videotaped. During the age-2 assessment, mothers completed questionnaires and mothers and sons completed a series of interaction tasks. The visit began with a 15-min free play that was followed by a 5-min clean up task. Next the child and mother completed a delay of gratification task, the No Toys task (5 min, Smith & Pederson, 1988). The last three tasks in the assessment included the following: mothers and sons worked cooperatively with three toys; boys were exposed to a loud toy to measure boys' inhibition; and families prepared and ate a meal. The age-2 assessments lasted approximately 2.5 hours. When the boys were 3 (N = 112,93% retention) and 4 years of age (N = 109,91% retention), families participated in follow-up home visits, similar in structure and content used in the initial home visit, with a few alterations in the observation procedures to match the child's developmental status (e.g., No Toys Task became the Cookie Waiting Task at age 3, Marvin, 1977, and Gift Waiting Task at age 4, Dryden, DeKlyen, & Speltz, 1993). At age 4, there were no differences between the participants who remained in the study and those who did not participate in the age-4 assessment on income, F (1,118) =.01, ns, or maternal education, F (1,118) = 2.66, ns. By the age-4 assessment, 55 control families and 54 treatment families remained.

The main tasks utilized for the current study were three delay of gratification tasks. All three were chosen because each involved boys waiting and managing a frustrating situation. Caregivers instructed the boys to wait a brief period of time, and in the case of the Cookie and Present Wait Task to wait for a desired object while the caregiver completed questionnaires in the room, thus being available as a potential resource to the boys' self-regulation efforts. During each of the waiting tasks the caregivers were instructed to react in a manner that was most comfortable for them, while ensuring that the child did not gain or regain access to the desired object(s).

Each of the delay of gratification tasks followed the protocol described by the task developers. The No Toys task (Smith & Peterson, 1988) during the age-2 assessment occurred after free play toys were removed and placed into an opaque bin with locking lids. The 2-year-olds were then asked to wait for 5 min while their caregiver completed questionnaires. During the Cookie Waiting Task administered at the 3-year-old assessment, the free play toys were removed and stored in a similar fashion, and the caregivers were given a clear ziplock baggie with a cookie inside to hold for 3 min while they completed questionnaires (Marvin, 1977). Finally, for the Gift Waiting Task during the 4-year-old assessment, the child was asked to wait for a wrapped gift for 4 min (Dryden et al., 1993).

Measures

Boys' emotional self-regulation strategy use

The study employed an observational coding system based on Grolnick et al. (1996) and adapted by Gilliom et al. (2002). After comparing the original codes to Kopp's (1989) theoretical model, we created four emotional SRS codes. The rationale behind each code is discussed in turn below.

Emotion-focused active strategies included behaviors indicating that the child attempted to alter his emotional state but did not attempt to distract himself from the emotionally invoking situation (this behavior is described below). They included seeking comfort from a caregiver, accepting comfort from the caregiver, or self-soothing behaviors. Boys displaying emotion-focused active strategies did not appear to be attempting to change any aspect of the situation other than their own emotional state. Kopp (1989) discussed how these are early, more immature behaviors the child develops to cope with the situation.

Emotion-focused passive strategies are similar to emotion-focused active strategies in that the child appeared to be reacting solely to the emotion. However, in emotion-focused passive strategies the child did not overtly attempt to change his emotional state but instead engaged in non-active, non-goal oriented behavior. These boys appeared to remove themselves mentally from the situation, usually indicated by a blank expression on their face without focusing on anything for more than 4 s. Although Kopp (1989) did not directly address these behaviors in her model, they are theoretically distinct from both the emotion-focused active strategies already discussed and the planful strategies discussed next and were therefore kept separate.

Planful strategies were organized or monitoring strategies. They included both goal-oriented behavior aimed at occupying the child's attention and asking questions aimed at learning about the waiting situation (e.g., if the task will continue another 2 min the child may decide to engage in one behavior over another for that time period). An example of a planful strategy is singing or dancing around the room during the waiting period. The current study incorporated two codes from Grolnick's et al. (1996) original system, active distraction and information gathering, into the category of planful strategies. It should be noted, if the child repeatedly asked questions regarding the wait task that appeared to indicate the child was focused on the delay, the focus on delay object was coded instead of planful strategies.

Finally, the code focus on delay object captured the child's outward negative emotional expression or perseveration on the delay object during the waiting period. Although Kopp (1989) did not directly discuss the lack of emotional SRS, we inferred that boys who were not engaging in other emotional SRS behaviors could be classified as unable to emotionally self-regulate and therefore were focusing on the delay object. Two examples of behaviors that would be coded as focus on delay object include attempts to get into the box of forbidden toys or questions about the task such as “Can I have the cookie now?”

The four behavior categories were coded for their presence or absence during each 10-s interval during a delay of gratification task (5 min at age 2, 3 min at age 3, and 4 min at age 4). The codes are exhaustive. For each interval, the boy was coded as engaging in at least one of the behaviors. Furthermore, the codes are mutually exclusive with the exception of the emotion-focus active codes. The coder judged the predominant strategy represented by a specific behavior using the exemplars given in the coding manual. For the emotion-focused active codes, the child could be coded as engaging in sucking his thumb at the same time he engaged in another behavior such as focusing on the delay object.

Due to the differing lengths of the task at different assessments, the ratio of the number of intervals the child employed a strategy to the total possible intervals was used as the final score for each strategy. Therefore, a mean of .69 for an SRS indicates that the SRS was used during 69% of the intervals. Inter-rater reliability was calculated on 20% of the tapes and was found to be satisfactory (ICC = .76–.96). After the coders reached reliability they were responsible for coding approximately 2–5 tapes per week depending on their availability and length of involvement in the research project. The five coders were unaware of the study hypotheses and were blind to the treatment group status of families.

To ensure the task adequately induced boys' emotions, the coders recorded the number of intervals in which the child showed some level of obvious negativity or distress (e.g., crying, whining, or fussing) or positivity (e.g., smiling, laughing). To code emotion as present, the child needed to show clear evidence of the emotion, such as crying or whining. Subtle indications of emotion such as a slight downturn of the mouth possibly indicating a frown did not count. The frequency of boys who displayed at least two 10-s intervals of negativity or positivity for each assessment is shown in Table 2. In the current sample 53.5% of 2-year-olds and 34.8% of 3-year-olds expressed negative emotion during at least two intervals. In comparison, Gilliom et al. (2002) found that 3.5 year-olds showed negativity during approximately 30% of a cookie waiting task, and Grolnick et al. (1996) found approximately 85% of the 2-year- olds expressed at least some negative emotion during the parent-active waiting task. Both Gilliom et al.'s and Grolnick et al.'s waiting tasks were similar in their focus on children's ability to tolerate a frustrating situation involving a delay, but in those studies tasks were administered in the lab. Furthermore, Grolnick et al.'s system examined more fine-grained emotional items, such as clenching of the jaw, than were coded in the current study. Our home visits had the advantage of allowing the boys to feel more comfortable and possibly exhibit more normative behavior than in a laboratory. However, we could not include a more fine-grained coding system because the child's face was not always fully recorded with one camera. In many laboratories a multiple camera set up can more reliably capture the child's face.

Table 2.

Number of children who showed at least two intervals of observed negative or positive child emotion

| Negative Emotion | Positive Emotion | |

|---|---|---|

| Age 2 (N = 112) | 60 (53.5%) | 36 (32.1%) |

| Age 3 (N = 109) | 38 (34.8%) | 28 (25.6%) |

| Age 4 (N = 102) | 16 (15.5%) | 32 (30.7%) |

Results

Descriptive Statistics

To inform interpretation of the results, descriptive statistics are provided to illustrate the risk level of the sample. The sample was screened for both family risk factors, such as maternal depressive symptoms, and child behavior problems. As can be seen in Table 2, at the initial screening, caregiver reports of boys' behavior problems on both the Eyberg Intensity (M = 122.30; SD = 27.00) and Problem behavior (M = 12.25; SD = 6.25) scale were well above normative means (Intensity = 98, Problem = 7).

Because the prevention program from which the sample was drawn addressed behavioral issues of the boys with the parents, differences on emotional SRS between the boys in the treatment and control group were examined. As a reminder, those families who were randomly assigned to the treatment group were offered the opportunity to meet with a consultant around parenting and family issues whereas those in the control group only participated in the annual assessments. Of the families assigned to the treatment group, the average number of times the families met with a parent consultant was 3.26 (SD = 2.34) (Shaw et al, 2006). ANOVAs were conducted at each age for each of the four SRS strategies over time by treatment status. No significant differences were found in emotional SRS use between boys in the treatment and control conditions for all SRS (all ps > .05) except active emotion (p < .05). Although the overall F test was significant for active emotion, F (3, 113) = 3.03, p < .05, the pattern of results was inconsistent. At age 2 there was no significant difference between groups, as would be expected given random assignment and no treatment was delivered prior to this assessment (Mtx = .29, SDtx = .33; Mct = .32, SDct = .34). At age 3 the treatment group used active emotion SRS significantly more than the control group (Mtx = .20, SDtx = .29; Mct = .11, SDct = .22). By age 4 that trend was reversed and the treatment group used active emotion SRS less frequently (Mtx = .08, SDtx = .15; Mct = .16, SDct = .31). Given the lack of a consistent difference between treatment and control group boys, for the remaining analyses treatment status was entered as a covariate for equations examining active emotion SRS only; for the other SRS, the boys were collapsed into one sample.

Data Analyses

To examine the patterns of change in the boys' SRS strategies at ages 2, 3 and 4, both variable- and person-oriented data analyses were conducted. To explore the first hypothesis examining whether boys on average would move from less to more sophisticated strategies over time, a variable-centered, repeated-measures ANOVA was used to explore boys' ratio of use of each SRS over time. Second, a person-oriented, semi-parametric group-based method (Nagin, 1999) for modeling developmental trajectories was used to identify groups of boys who displayed distinct trajectories of SRS use over time.

As this is a longitudinal study utilizing observational data collection, data were lost because of both subject attrition (5 families between age 2 and 3; 4 families between age 3 and 4) and problems encountered in coding (i.e., sound or video quality; 3 families from original 120 recruited). Different methods for handling missing data were used for each of the two analytic methods. For the repeated-measures ANOVA, the analyses were computed utilizing the expectation-maximization (EM) imputation method. Within the person-oriented analysis, the PROC TRAJ program assumes the data are missing at random and uses a general quasi-Newton procedure (Dennis, Gay, & Welsch, 1981; Dennis & Mei, 1979), allowing for analysis of the full sample (Nagin, 1999; 2005).

Variable-centered Approaches to Understand Developmental Change

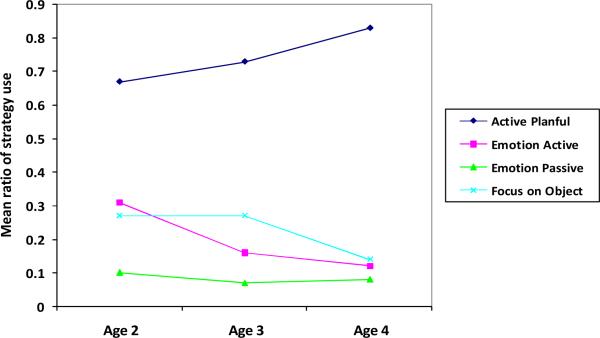

The first goal was to examine the change in boys' mean ratio of use of specific SRS to total intervals in the task from age 2 to 4. Figure 1 displays the boys' mean usage of each SRS at each time point, excluding imputed data. In contrast, Table 3 presents the mean usage at each age following the use of the EM imputation method. At all three time points, planful strategies were the most common strategy boys employed (67–83% of the time). In addition, though infrequent, emotion-focused passive strategies were fairly stable over time (10% of the time or less), whereas focus on the delay object became less common over time (moving from 27% to 14%).

Figure 1.

Developmental change of SRS over time.

Table 3.

Mean SRS change over time (N = 117)

| Age 2 | Age 3 | Age 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Planful Strategies | .67c | .28 | .73c | .30 | .83ab | .22 |

| Emotion Active Strategies | .30bc | .33 | .16a | .26 | .12a | .24 |

| Emotion-focus passive strategies | .10 | .18 | .07 | .15 | .08 | .16 |

| Focus on Delay Object | .27c | .28 | .27c | .29 | .14ab | .19 |

Note.

significantly different from age 2.

significantly different from age 3.

significantly different from age 4.

Four repeated measures ANOVAs were used to examine the mean ratio change within each SRS over time (see Table 3). For each equation, the eta squared is provided, which gives an estimate of the variability explained by the equation, similar to an R2. Three of the four analyses found significant differences over time. The main effect for time was significant for the child's use of planful strategies F (2, 115) = 11.38 p < .001, η2= .17, focus on delay object F (2, 115) = 17.15, p < .001, η2= .23, and emotion-focused active strategies F (2, 114) = 8.23, p < .01, η2= .07. In accord with Kopp's (1989) model, planful strategies and emotion-focused active strategies showed mean change over time in the expected direction. Post-hoc tests using Bonferroni's correction indicated that boys showed lower rates of planful strategies and higher rates of focus on delay object at ages 2 and 3 in comparison to age 4. For emotion-focused active strategies, boys displayed significantly higher rates at age 2 versus ages 3 and 4, but no differences were found between ages 3 and 4. For boys' use of emotion-focused passive strategies, the main effect for time was not significant F (2, 115) = .97, ns.

Individual Differences in Emotional SRS

Although the use of variable-centered analysis provides critical information about changes in the use of SRS by the entire sample, by relying completely on this method, individual differences in developmental patterns among subgroups may be lost (Siegler, 1987). To supplement these variable-oriented analyses, group-based semi-parametric modeling (Nagin, 2005) was applied to identify distinct trajectories of individual SRS from ages 2 to 4.

The person-based trajectory modeling method uses a multinomial modeling strategy that can identify trajectories of individuals longitudinally using maximum likelihood parameters in a latent class model (Nagin, 1999). A censored normal model was used to account for the fact that the nature of the data (i.e., ratio) is artificially truncated at 0 and 1.

An important aspect to the trajectory modeling approach is the determination of the number of groups within the population that best fit the data. As recommended, the current study relied principally on the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC; D'Unger, Land, McCall, & Nagin, 1998; Kass & Rafterty 1995) to determine the most optimal model fit for the data. Using this procedure, individuals are assigned to trajectory groups based on their likelihood of showing similar patterns of development to other boys in the sample over time, as evidenced by their posterior probability to be in one of x number of groups.

To identify the most optimal model of SRS, models are typically tested with two, three, and four trajectory groups. Because the current sample included relatively few subjects (i.e., N varied from 103 to 120 at different times) and the minimum number of data points for using semi-parametric modeling (i.e., at least three data points are required and a minimum sample size of at least 100 is recommended), models identification was limited to one to three groups. As a result, some caution is warranted in interpreting the findings from the current study, as findings with smaller samples should be seen as suggestive and preliminary and small sample sizes increase the likelihood of small trajectory groups emerging due to error (Loughran & Nagin, 2006; Nagin, personal communication, August 10, 2007). Individual groups were tested for the optimum fit, including intercept, linear, and quadratic trajectories for all groups.

Models were obtained for all strategies with the exception of emotion-focused passive strategies. Due to the small sample size and low base rate of this behavior, it was not possible to obtain a stable model for this strategy. For this strategy, group-based modeling was not the optimal strategy, and a single trajectory best approximated the data. The trajectory of single groups would be identical to the developmental path for emotion-focused passive strategies presented in Figure 1.

The Baysian Information Criteria for each of the modeled strategies is displayed in Table 4. The BIC is a log-likelihood statistic, provided as part of the PROC TRAJ output, which indicates the model that is most parsimonious for the data. PROC TRAJ utilizes significance testing to compare the BIC of the more complex model against the BIC of the simpler model. The final models selected as the best fit for each of the SRS groups include those with the highest BIC values and significant parameters. Models with lower BIC values or parameters that failed to reach significance were rejected during model selection. According to Nagin (2005), it is left to the analyst to use professional judgment of the best fitting model given both theory and the BIC statistics and parameters. Using this criterion, the 2-group models were deemed to be the best fit for emotion-focused active, planful strategies, and for focus on delay object. Next to each tested model for individual SRS in Table 4, a number representing the intercept (0), linear (1), or quadratic (2) trajectories is provided in parentheses (e.g., “2 1 1“ indicates one quadratic and two linear trajectories). The first row in the table presents the model chosen as the best fit. In addition to the BIC scores, the posterior probabilities, or the probability for membership into the trajectory group, for each of the models, can be used to judge model fit (see Table 5). The probabilities in the models judged to be the best fit for the current data indicate that all trajectory groups for the three models selected for the SRS were above the minimum level of 0.70 suggested by Nagin (2005). A more detailed discussion of the use of BIC and posterior probabilities in model selection and the PROC TRAJ procedure can be found in Jones, Nagin, and Roeder (2001).

Table 4.

Model fit statistics for the trajectory analysis for each SRS

| MODEL | BIC |

|---|---|

| Emotion Active 2-Group | |

| Linear, Linear Model (1 1) | −243.15* |

| Quadratic, Quadratic Model (2 2) | −248.04 |

| Quadratic, Quadratic, Quadratic (2 2 2) | −251.48 |

| Planful Strategies 2-Group | |

| Linear, Intercept Model (1 0) | −177.61* |

| Quadratic, Quadratic (2 2) | −185.25 |

| Quadratic, Quadratic, Quadratic (2 2 2) | −186.16 |

| Focus on Delay 2-Group | |

| Linear, Intercept Model (1 0) | −195.57* |

| Quadratic, Quadratic (2 2) | −203.58 |

| Quadratic, Quadratic, Quadratic (2 2 2) | −209.01 |

Parameters were significant for this model.

Table 5.

Probabilities of group membership by SRS for trajectory analysis

| SRS | Group | N | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion-Focused | |||

| Active | |||

| 1 (Linear Trajectory) | 85 | 0.97 | |

| 2 (Linear Trajectory) | 32 | 0.98 | |

| Planful Strategies | |||

| 1 (Linear Trajectory) | 110 | 0.95 | |

| 2 (Intercept Trajectory) | 7 | 0.83 | |

| Focus On Delay | |||

| Object | |||

| 1 (Linear Trajectory) | 110 | 0.97 | |

| 2 (Intercept Trajectory) | 7 | 0.89 |

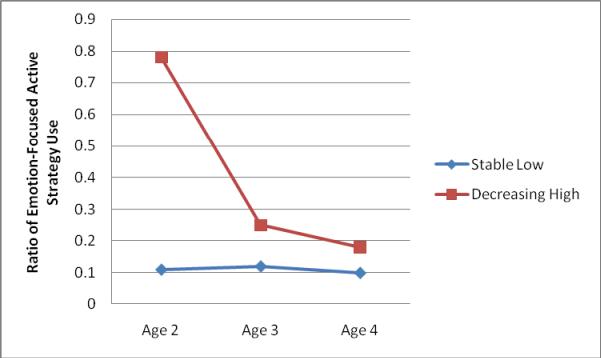

As can be seen in Figure 2, a 2-group model was identified for emotion-focused active strategy use. Over 70% of the sample (stable-low group) was included in a group that used emotion-focused active strategies infrequently at all three ages, approximately one tenth of the time at each time point. For the remaining boys (decreasing-high group), emotion-focused active strategy use occurred more frequently at age 2, around half of the time, and then steeply declined between the ages of 2 and 3. By age 3, this group of boys was using emotion-focused active strategies less than 30% of the time.

Figure 2.

2 group trajectory model of emotion active strategies.

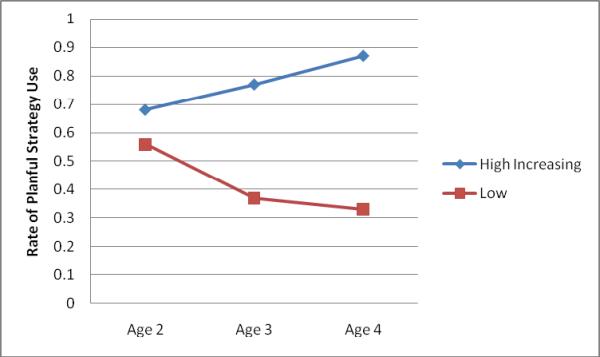

As previously mentioned, planful strategy use was the most frequent type of strategy for the boys in this sample. For most of the boys, the ratio of intervals in which they engaged in planful strategies increased as they grew older. Most boys in this group were using planful strategies nearly 70% of the time (see Figure 3 and Table 5). For a small minority of boys (decreasing group, n = 7), use of planful strategies decreased over time, starting at less than 60% of the time at age 2, and dropping, by age 4, to slightly more than 30% of the time.

Figure 3.

2 group trajectory model of planful strategies.

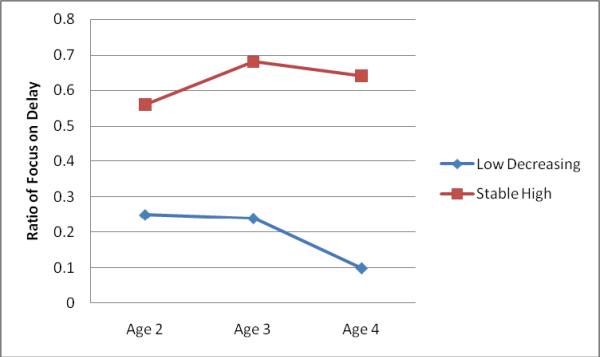

Two groups emerged for the SRS, focus on the delay object. The largest (n = 110) group of boys infrequently used focus on the delay object at all three time points, although the use gradually decreased between ages 2 and 4 (see Figure 4). A small group of boys (n = 7) used focus on the delay object strategy frequently at each of the three time points, without significant decrease over time.

Figure 4.

2 Group trajectory model of focus on delay strategies.

Discussion

Kopp's (1989) theory suggests that the infant moves from other-comfort (i.e., a person or transitional object) to more independent planful strategies such as distraction during the toddler and preschool period (Diener & Mangelsdorf, 1999; Grolnick et al., 1996; Kopp, 1989). The current study provides some support for this theory.

Decreases in emotion-focused active strategies were found over time, supporting the notion that as boys mature, their emotional SRS change from using a transitional object such as a sippy cup or blanket to being able to engage in more independent and cognitively sophisticated strategies (Kopp, 1989). The trajectory analysis indicates that the majority of boys used fairly low levels of emotion-focused active strategies at age 2 and that these rates remained fairly stable over time. For around one-quarter of the boys, emotion-focused active strategies were used very frequently at age 2; however, these boys used emotion-focused active strategies less frequently as they matured, such that by age 4, this smaller group was using emotion-focused active strategies at a frequency that was only slightly higher than the stable-low trajectory group. The 25% of boys using high rates of emotion-focused active strategies at age 2 were delayed in their progression away from these strategies. However, by age 4 most had caught up to the majority group.

The current data appear to support Kopp's (1989) theorized increase in boys' use of planful strategies over time, such as distraction, a strategy found in previous research to be related to effective emotion self-regulation (Gilliom et al., 2002; Silk et al., 2006; Trentacosta & Shaw, 2009). Both the mean ratio of planful strategies and the trajectory analysis indicate that the majority of boys were already utilizing planful strategies at age 2. However, for a small group of boys, the use of planful strategies decreased over time.

The overall high rates of planful strategies may be the result of the definitional characteristics of this strategy in the coding system. Most behaviors that were not definable as one of the other SRS strategies and did not show clear, observable dysregulation on the child's part were ultimately coded as planful strategies. It is possible that boys who use interpersonal distractions, such as engaging in conversations with their caregivers are different than boys who engage in solitary means of distraction, such as twirling around the room or dancing. A more nuanced definition of planful strategies separating self- versus dyadic-distraction may provide richer information on the developmental changes in use of this SRS over the first years of life.

In addition to changes in emotion self-regulation strategies, significant decreases in boys' focus on the delay object supports Kopp's (1989) theory that self-control abilities increase during this period of development (Stansbury & Zimmerman, 1999). The results of the current study support the supposition by Stansbury and Sigman (2000) and Mangelsdorf et al. (1995) that as toddlers increase their use of planful strategies, their tendency to focus on a delay object decreases. This decrease in focus on delay object has been found to be important because this strategy was related to increases in child negativity during a waiting task and later teacher-reported externalizing behavior at formal school entry in a previous study (Gilliom et al., 2002).

One interesting finding is the stability of the boys' use of emotion-focused passive strategies. Although few studies to date have specifically examined boys' development of emotion-focused passive strategies, previous research suggests that the use of these strategies may arise from the child's observations of the parent's own coping mechanisms, stemming from the parent either overtly or covertly modeling this strategy to the child (Silk et al., 2006). An alternative explanation is that passive coping to emotional situations is associated with a more stable, personality-driven regulation strategy among individuals who are more socially inhibited (Asendorpf, 1991). Research suggests that emotion-focused passive strategies may be related to boys ruminating about their feelings of anger or sadness, are ineffective strategies for dealing with negative emotions, and place individuals at risk for psychopathology (Blair et al., 2004; Silk et al., 2006). The findings regarding emotion-focused passive strategies and child outcomes are mixed and may vary according to child gender, with girls who passively wait experiencing higher risk of internalizing and externalizing problems than boys who use the same strategy (Gilliom et al., 2002; Silk et al., 2006). Thus, in the present sample of boys, the use of emotion-focused passive strategies may pose relatively smaller risk for the development of behavior problems than in a sample of girls. Future research should explore the origins and development of emotion-focused passive strategies in samples that include boys and girls.

Limitations and Future Research

The current study has several limitations. First, a common problem when studying emotional self-regulation is a confound between the measurement of emotion and the use of regulation strategies. If the task does not elicit high levels of emotion, it may be due to the child's adept emotional self-regulation or the task being insufficiently stressful to elicit emotion. Ethical concerns arise in not wanting to elicit negative emotions to the point as to raise concerns about adverse effects on boys' mental health. Although the rates of negative emotion elicited in the current study were not exceptionally high, it is difficult to compare these rates to previous research, as different studies utilized more or less conservative criteria for defining negative emotions. In addition, the current study employed similar but slightly different tasks across a 3-year period to account for developmental changes in social maturity (e.g., decreases in tantruming between ages 2 to 4). Due to differences in the delay of gratification tasks (e.g., cookie at age 3 and toy at age 4), it is possible that differences across the time points are due to changes in the tasks or individual preferences in delay objects, rather than developmental changes in the participants. For example, the study followed the delay of gratification task developers' protocol, specifically around administration time. The children therefore waited different amounts of time at each age. In addition, anecdotally some children displayed greater desire for one delay object (e.g. cookie) than the gift at the next assessment year. It is not possible to completely tease apart personal preference for the delay object from developmental maturity. Even with differences in the task administration across ages, the data in the current study offer support to Kopp's (1989) model that rates of negative emotion decline and rates of more planful SRS appear to remain relatively stable during this period. However, future research needs to more thoroughly investigate solutions to this regularly occurring challenge when measuring emotional SRS.

Second, the boys were observed during a delay of gratification task, and it is possible the task used to elicit boys' emotional SRS may not have been ecologically valid compared to frustrating situations that occur in the child's daily life. However, past research using similar laboratory-based tasks has linked boys' SRS to boys' subsequent emotion regulation skills and externalizing problem behaviors outside of the laboratory context (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 1994; Gilliom et al., 2002). Future research should include multiple methods (e.g., observations, interviews, and vignettes across youth and parent informant), including assessment of child behavior outside of a laboratory to increase generalizability of findings.

Third, the sample includes primarily European- and African-American boys from an urban community selected for their risk of developing behavior problems. The results of the current research, therefore, can only be generalized to a similar population. The exclusive focus on boys is particularly noteworthy given the unique self-regulatory styles that may emerge for males and females based on gender socialization, biology, or a combination. For example, previous research demonstrates that boys may use more venting and express more negative emotion during frustrating situations than girls (Cole, Zahn-Waxler, & Smith, 1994; Fabes & Eisenberg, 1992). Therefore, it is possible that girls' SRS profiles may differ from the trajectories found in the present study of boys. Although the current study contributes to the literature by exploring the development of emotional self-control strategies longitudinally in a sample of boys at risk for behavior problems, more longitudinal work with both normative samples and at-risk samples that include more diversity in socioeconomic status, ethnicity, culture, community type (e.g., rural, suburban), and gender are needed.

Finally, research exploring emotional SRS needs to continue to explore developmental data in multiple ways including both group mean differences and individual change over time using both variable- and person-centered approaches. For example, insecure attachment or parenting that is characterized as harsh or rejecting may impede the development of adaptive SRS (e.g., planful strategies) and reinforce relatively maladaptive strategies (e.g., focus on the delay object). Previous research provides some support for these predictions when SRS were measured at a single time point (e.g., Gilliom et al., 2002), but future research should examine individual or relationship factors as predictors of unique trajectories of SRS from toddlerhood through the preschool period. Finally, trajectories of decreased emotion active strategies and focus on the delay object may enhance school readiness by promoting the coordination of cognition and emotion (Blair, 2002) and positive behavioral outcomes (Morris et al. 2010). For example, do boys who show temporary delays in the acquisition of more protective strategies and rely more heavily on emotion-focused active strategies in toddlerhood, but catch up to peers in the preschool period, have outcomes more similar to those boys with normative patterns of SRS at all ages? If the boys who catch up have similar outcomes to typically developing peers, the development of protective strategies would be an important focus of clinical interventions. Unfortunately, the study's modest overall sample size and the even smaller size of some trajectory groups precluded an analysis of antecedents and outcomes of trajectory group membership in the present study. Despite these limitations, the current findings combined with the suggestions for future research, highlight the importance of broadening the field's understanding of the development of self-regulation in children, particularly those who are heightened risk for behavior problems.

The current findings combined with the suggestions for future research can enhance early prevention and treatment efforts so that all boys, particularly boys at risk for behavior problems due to poverty and related socioeconomic factors (e.g., neighborhood dangerousness, exposure to deviant peers), can have the opportunity to develop adaptive emotional self-regulatory skills. In order to design effective prevention and intervention efforts, a strong understanding of the etiology of adaptive and maladaptive developmental processes is required (Sroufe, 2009). The current paper provides an initial empirical step to describing the developmental pathways of emotional SRS in at-risk children.

Acknowledgments

The work on this manuscript was conducted by the authors while at the Pitt Parents and Children Laboratory, within the Department of Psychology at the University of Pittsburgh. The primary goal of the PPCL is to advance our understanding of vulnerability and resilience among children at-risk for maladaptive psychosocial outcomes. The authors would like to thank the reviewers their thoughtful contributions to the manuscript. We would also like to thank the families of the Pitt Early Steps Project for their participation. Note that research was supported by grant MH06291 from the National Institute of Mental Health and grant DA016110 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

References

- Asendorpf JB. Development of inhibited children's coping with unfamiliarity. Child Development. 1991;62:1460–1474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Taylor SE. A stitch in time: Self-regulation and proactive coping. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:417–436. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Cassidy J. Mothers' self-reported control of their preschool children's emotional expressiveness: A longitudinal study of associations with infant-mother attachment and children's emotion regulation. Social Development. 2003;12:477–495. [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children's functioning at school entry. American Psychologist. 2002;57:111–127. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair KA, Denham SA, Kochanoff A, Whipple B. Playing it cool: Temperament, emotion regulation and social behavior in preschoolers. Journal of School Psychology. 2004;42:419–443. [Google Scholar]

- Braungart-Rieker JM, Stifter CA. Infants' responses to frustrating situations: Continuity and change in reactivity and regulation. Child Development. 1996;67:1767–1779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody LR. Gender, emotional expression, and parent-child boundaries. In: Kavanaugh RD, Zimmerberg B, Fein-Glick S, editors. Emotions: Interdisciplinary perspectives. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1995. pp. 139–170. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JC, Mezzacappa E, Beardslee WR. Characteristics of resilient youths living in poverty: The role of self-regulatory processes. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:139–162. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins S. Temperament and emotion regulation: Multiple models of early development. In: Beuregard M, editor. Consciousness, emotional self-regulation and the brain. John Benjamins; Amsterdam, Netherlands: 2004. pp. 35–59. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Howse RB. Individual differences in self-regulation: Implications for childhood adjustment. In: Philippot P, Feldman RS, editors. The regulation of emotion. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2004. pp. 307–332. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Michel MK, Teti LO. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(2–3 Series Number 240):73–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Zahn-Waxler C, Fox NA, Usher BA, Welsh JD. Individual differences in emotion regulation and behavior problems in preschool children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:518–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Zahn-Waxler C, Smith KD. Expressive control during a disappointment: Variations related to preschoolers' behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:835–846. [Google Scholar]

- Conway AM. Girls, aggression and emotion regulation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:334–339. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deiner ML, Mangelsdorf SC. Behavioral strategies for emotion regulation in toddlers: Associations with maternal involvement and emotional expressions. Infant Behavior & Development. 1999;22:569–583. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA. Emotional development in young children. The Guilford Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis JE, Gay DM, Welsch RE. An adaptive nonlinearleast-squares algorithm. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software. 1981;7:348–383. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis JE, Mei HHW. Two new unconstrained optimization algorithms which use function and gradient values. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications. 1979;28:453–483. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA. Coordinating responses to aversive stimuli: Introduction to a special section on the development of emotion regulation. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:339–342. [Google Scholar]

- Dryden M, DeKlyen M, Speltz M. Self-control and emotion regulation in preschool boys: Do behavior problems or attachment status make a difference?. The biennial convention of the Society for Research in Child Development; Seattle, WA. 1993, April. [Google Scholar]

- D'Unger AV, Land KC, McCall PL, Nagin DS. How many latent classes of delinquent/criminal careers? Results from mixed Poisson regression analyses of London, Philadelphia, and Racine cohort studies. American Journal of Sociology. 1998;103:1593–1630. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Murphy B, Maszk P, Holmgren R, et al. The relations of regulation and emotionality to problem behavior in elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Nyman M, Bernzweig J, Pinuelas A. The relations of emotionality and regulation to children's anger-related reactions. Child Development. 1994;65:109–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenbeck H, Kohlmann CW, Lohaus A. Gender differences in coping strategies in children and adolescents. Journal of Individual Differences. 2007;28:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N. Young children's coping with interpersonal anger. Child Development. 1992;63:116–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Klein PS. Toddlers' self-regulated compliance to mothers, caregivers, and fathers: Implications for theories of socialization. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:680–692. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.4.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T. Infant gaze aversion and heart rate during face-to-face interactions. Infant Behavior and Development. 1981;4:307–315. [Google Scholar]

- Ganiban JM, Bridges L, Supplee L, Brewster A. The development of emotion regulatory processes during infancy. 1998 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom M, Shaw DS, Beck JE, Schonberg MA, Lukon JL. Anger regulation in disadvantaged preschool boys: Strategies, antecedents, and the development of self-control. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:222–235. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick WS, Bridges LJ, Connell JP. Emotion regulation in two-year-olds: Strategies and emotional expression in four contexts. Child Development. 1996;67:928–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick WS, McMenamy JM, Kurowski CO. Emotional self-regulation in infancy and toddlerhood. In: Balter L, Tamis-LeMonda C, editors. Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues. Garland; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociological Methods and Research. 2001;29:374–393. [Google Scholar]

- Karoly P. Mechanisms of self-regulation: A systems view. Annual review of psychology. 1993;44:23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, Raferty AE. Bayes factors. Journal of American Statistical Association. 1995;90:773–795. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Shaw DS. Developmental influences on young girls' behavioral and emotional problems. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:95–113. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Kaack A. Effortful control as a personality characteristic of young children: Antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1087–1112. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray K, Coy KC. Inhibitory control as a contributor to conscience in childhood: From toddler to early school age. Child Development. 1997;68:263–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A developmental view. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:343–354. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Hoff E. Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52:377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Dishion TJ. Early predictors of male delinquency: A review. Psychological Bulletin. 1983;94:68–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughran T, Nagin DS. Finite sample effects in group-based trajectory models. Sociological Methods and Research. 2006;35:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf SC, Shapiro JR, Marzolf D. Developmental and temperamental differences in emotion regulation in infancy. Child Development. 1995;66:1817–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin RS. An ethological-cognitive model for the attenuation of mother-infant attachment behavior. In: Alloway TM, Krames L, Pliner P, editors. Advances in the study of communication and affect: Vol. 3. The development of social attachments. Plenum Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez JL, Fantuzzo J, Cicchetti D. Profiles of social competence among low-income African American preschool children. Child Development. 2002;73:1085–1100. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Fine SE, Gouley KK, Seifer R, Dickstein S, Shields A. Showing and telling about emotions: Interrelations between facets of emotional competence and associations with classroom adjustment in Head Start preschoolers. Cognition and Emotion. 2006;20:1170–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Terranova AM, Kithakye M. Concurrent and longitudinal links between children's externalizing behavior in school and observed anger-regulation in the mother-child dyad. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2010;32:48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS. Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pauli-Pott U, Mertesacker B, Beckmann D. Predicting the development of infant emotionality from maternal characteristics. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:19–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Rothbart MK. Developing mechanisms of self-regulation. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:427–441. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC. Placing emotional self-regulation in sociocultural and socioeconomic contexts. Child Development. 2004;75:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Posner MI, Kieras J. Temperament, attention, and self-regulation. In: McCartney K, Phillips D, editors. Handbook of early childhood development. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 338–357. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ziaie H, O'Boyle CG. Self-regulation and emotion in infancy. In: Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, editors. Emotion and its regulation in early development Vol. 55: New Directions for Child Development. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1992. pp. 7–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Supplee LH, Gardner F, Arnds K. Randomized trial of a family-centered approach to the prevention of early conduct problems: 2-year effects of the family check-up in early childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Lacourse E, Nagin D. Developmental trajectories of conduct problems and hyperactivity from ages 2 to 10. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:931–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegler RS. The perils of averaging data over strategies: An example from children's addition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1987;116:250–264. [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Shaw DS, Forbes EE, Lane TL, Kovacs M. Maternal depression and child internalizing: The moderating role of child emotion regulation. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:116–126. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PB, Pederson DR. Maternal sensitivity and patterns of infant-mother attachment. Child Development. 1988;59:1097–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. The concept of development in developmental psychopathology. Child Development Perspectives. 2009;3(3):178–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansbury K, Sigman M. Responses of preschoolers in two frustrating episodes: Emergence of complex strategies for emotion regulation. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2000;161:182–202. doi: 10.1080/00221320009596705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansbury K, Zimmerman LK. Relations among child language skills, maternal socialization of emotion regulation, and child behavior problems. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 1999;30:121–142. doi: 10.1023/a:1021954402840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Nebraska symposium on motivation, 1988: Socioemotional development. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln, NE: 1990. Emotion and self-regulation; pp. 367–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda S, Fogel A. Infant response to the still-face situation at 3 and 6 months. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:532–538. [Google Scholar]

- Trentacosta CJ, Shaw DS. Emotion regulation strategies, peer rejection, and antisocial behavior: Developmental associations from early childhood to early adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;30:356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lieshout CFM. Young children's reactions to barriers placed by their mothers. Child Development. 1975;46:348–356. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn BE, Kopp CB, Krakow JB. The emergence and consolidation of self-control from eighteen to thirty months of age: Normative trends and individual differences. Child Development. 1984;55:990–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner RS, Cassidy KW, Juliano M. The role of social-cognitive abilities in preschoolers' aggressive behavior. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2006;24:775–799. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MK, Tronick EZ, Cohn JF, Olson KL. Gender differences in emotional expressivity and self-regulation during early infancy. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:175–188. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman LK, Stansbury K. The influence of temperamental reactivity and situational context on emotion-regulatory abilities of 3-year-old children. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2003;164:389–409. doi: 10.1080/00221320309597886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]