Abstract

Motivation: 454 pyrosequencing, by Roche Diagnostics, has emerged as an alternative to Sanger sequencing when it comes to read lengths, performance and cost, but shows higher per-base error rates. Although there are several tools available for noise removal, targeting different application fields, data interpretation would benefit from a better understanding of the different error types.

Results: By exploring 454 raw data, we quantify to what extent different factors account for sequencing errors. In addition to the well-known homopolymer length inaccuracies, we have identified errors likely to originate from other stages of the sequencing process. We use our findings to extend the flowsim pipeline with functionalities to simulate these errors, and thus enable a more realistic simulation of 454 pyrosequencing data with flowsim.

Availability: The flowsim pipeline is freely available under the General Public License from http://biohaskell.org/Applications/FlowSim.

Contact: susanne.balzer@imr.no

1 INTRODUCTION

Second-generation sequencing techniques have revolutionized DNA sequencing. In comparison with Illumina (Solexa/Genome Analyzer) and Applied Biosystems (SOLiD), 454 pyrosequencing stands out with its longer reads (up to ~500 bp). However, higher sequencing error rates compared with traditional Sanger sequencing and the lack of a detailed understanding of error characteristics still hamper the effective utilization of pyrosequencing.

In de novo whole-genome sequencing, high coverage may compensate for erroneous sequences. However, erroneous reads are problematic for SNP detection (Quinlan et al., 2008) and especially for metagenomics, as they can lead to a considerable overestimation of diversity in a sample (Quince et al., 2009). Hence, there has been a strong focus on examining the quality of 454 pyrosequencing data and noise removal. Also artificial duplicates are an important issue, because they may lead to incorrect conclusions about the abundance of species and genes (Gomez-Alvarez et al., 2009).

1.1 The 454 pyrosequencing technology

The 454 pyrosequencing technology is based on sequencing-by-synthesis which is performed in parallel on around one million beads deposited in wells on a plate. Each bead carries around 10 million molecules resulting from emulsion PCR (emPCR) starting from one single DNA fragment. The sequencing is performed by cyclic flowing (T, A, C, G) of nucleotide reagents over the plate, every bead giving rise to at most one DNA sequence (‘read’). Each flow produces a light signal in each of the beads, either a very weak signal (‘negative flow value’, in practice being between 0 and 0.5, indicating that no base was incorporated) or a stronger signal (‘positive flow value’), proportional to the length of a homopolymer run (Margulies et al., 2005).

This chemical process implicates two characteristics that are intrinsic to 454 pyrosequencing data: when the light signal is too strong or too weak, this leads to an over- or under-call for the corresponding nucleotide type. For example, a flow value of 2.48 for nucleotide C gives a homopolymer length of two, while a flow value of 2.52 will give three nucleotides. Apparent substitution errors can occur when an over-call follows an under-call or vice versa. Compared with the called DNA sequence, the underlying flow values thus contain additional information relevant for base calling accuracy and for comparison of reads, which is why analyses often are carried out in ‘flowspace’ as opposed to ‘nucleotide space’.

The latest 454 pyrosequencing version, GS FLX Titanium (referred to as Titanium in the rest of the paper), uses 200 flow cycles, which corresponds to 800 flows. The results of one sequencing run include the light signal intensity data (‘flow values’) for each well and the base called DNA sequence together with quality information. This is stored in a binary SFF (standard flowgram format) file.

1.2 Duplicate reads

Earlier studies have revealed that between 4–44% (Niu et al., 2010) and 11–35% (Gomez-Alvarez et al., 2009) of sequences in a typical metagenomic dataset are exact or almost-exact duplicates. Both tools 454 Replicate Filter (Gomez-Alvarez et al., 2009) and cd-hit-454 (Niu et al., 2010) are based on the CD-HIT clustering algorithm (Li and Godzik, 2006) and provide a fast way of removing duplicates from pyrosequencing data. While this is a crucial step for the success of metagenomic studies based on 454 pyrosequencing data, we have not observed a comparably high percentage of exact or almost-exact duplicates in shotgun data generated in the context of projects we are involved in.

1.3 Erroneous reads

There are several factors that account for erroneous base calls or reads, especially inaccuracies in the sequencing chemistry, leading to slightly too high or low flow values, and carry-forward and incomplete extension errors (Margulies et al., 2005), accumulating over the read, which reflects the stochastic nature of the base incorporation chemistry. Furthermore, it has been shown that a low percentage of reads accounts for a high percentage of errors (Huse et al., 2007) and that sequencing quality decreases toward the end of a read (Balzer et al., 2010; Hoff, 2009). We have earlier described the characteristics of these inaccuracies, calculated the empirical distributions of flow values and included the results in our simulation tool flowsim (Balzer et al., 2010). However, these models do not adequately explain all the sequencing errors that we have observed, which is reflected in the fact that, when applied to whole-genome shotgun sequencing, our simulator produces data giving better assemblies than does real data (Section 3). Here, we report on a more careful examination of other error sources and suggest a new pipeline for a more realistic simulation of 454 pyrosequencing reads. We are not able to establish the exact source of these errors, but hypothesize that a portion of the errors are introduced during PCR library preparation.

1.4 Filtering and trimming

Some of these error patterns, but not all of them, are addressed by the 454 quality-trimming and read-filtering algorithms. A detailed description is given in the 454 manual (Roche Applied Science, 2008). However, in some applications, improved results are obtained when applying a stricter quality-filtering and -trimming (compared with 454 default settings) or using additional algorithms and tools. Several research groups have suggested methods for noise removal and quality-trimming, the requirements on data quality obviously varying with respect to applications. Whole-read filtering strategies include the complete removal of: chimeric reads, reads with undetermined bases (i.e. N's) or reads showing a certain percentage of flow values in the interval [0.5, 0.7] (termed ‘dubious flow values’) before reaching a certain flow cycle (Huse et al., 2007; Kunin et al., 2009; Quince et al., 2011). Trimming approaches focus on: a stricter read-trimming based on quality scores, adaptor removal [e.g. with LUCY (Chou and Holmes, 2001)], but also more sophisticated approaches such as multiple assembly strategies with reads obtained by applying several trimming settings (http://www.genome.ou.edu/informatics.html).

2 FACTORS FOR SEQUENCE QUALITY

In this study, we characterize error patterns derived from Titanium 454 pyrosequencing data and estimate to what extent different error types account for sequencing errors.

2.1 Adaptors

Sequences are limited in length by the number of flow cycles. Ideally, clones should be sufficiently long so that the end of the clone is not reached during sequencing, which means that also the adaptor is not reached. If the clone is shorter, the adaptor sequence will be included at the end of the read. This part of the sequence should be masked by the Roche analysis pipeline. However, the trimming procedure sometimes fails if only part of the adaptor is contained in the read or if there are sequencing errors in the adaptor sequence. We have observed both cases in shotgun data from different genomes.

In genome assembly, residual adaptors can block contig extension at the end of reads, especially in lower coverage regions and when working with assemblers that do not use a broad overlap window.

2.2 Pyrosequencing errors

The light signal strength from the chemical reaction in the sequencing process is the basis for correct determination of homopolymer lengths and hence responsible for data accuracy. Slightly too high or too low signal strengths can lead to over- or under-calls.

Carry-forward errors occur when the flushing between the flows is not sufficient and leftover nucleotides are present in a well. Also the incomplete extension of a template due to insufficient nucleotides within a flow can cause a read to get out-of-sync. These errors are collectively referred to as CAFIE. The Roche software adjusts the flow values in an attempt to correct for these errors, and both the flow values and the DNA data in the SFF file correspond to the corrected data (Roger Winer, Roche Diagnostics, personal communication).

2.3 Putative PCR errors

In a previous work, we derived empirical distributions from Dicentrarchus labrax (sea bass) Titanium data: by mapping 454 data to the originating reference genome (Kuhl et al., 2010), we characterized the distributions of flow values belonging to each homopolymer length (Balzer et al., 2010). These flow value distributions, one distribution per homopolymer length, overlap, causing over- and under-calls (Fig. 1). By examining them in detail, an interesting and hitherto unexplained pattern emerges: the flow value distributions often contain one major peak around the integral value representing the correct homopolymer length, but then also smaller peaks around the neighboring integral values (Figs 1 and 3). Although these neighboring peaks have been observed previously, we have not seen any convincing explanation for them. Hypothesizing that they are caused by errors in the emulsion PCR performed prior to sequencing, we make an attempt to estimate to what extent PCR errors contribute to the overall error rate.

Fig. 1.

Empirical flow values distributions (D.labrax) and derived intervals.

Fig. 3.

Flow value histograms for G.morhua mate-pair reads (forward matches, N=7 016 764). The y-axis is on a log10 scale. The 15 flow cycles correspond to the 42 positions of the linker sequence. The gray areas contain correct base calls. Subpeaks point toward putative PCR errors.

In order to quantify and compare the number of errors caused by overlapping distributions with the errors in neighboring peaks, we classified flow values according to narrow intervals around the integral values. Based on the empirical unsmoothed flow value distributions from D.labrax (Balzer et al., 2010), the intervals were constructed so that they would contain a certain percentage (the middle part) of flow values for each homopolymer length. The intervals are slightly asymmetric (Table 1), which corresponds to earlier observations that insertion errors are more common than deletions (Huse et al., 2007; Quinlan et al., 2008). For flow values of the 0-distribution (assumed not to correspond to incorporation of a nucleotide, i.e. negative flow values), the interval extends to one side only.

Table 1.

Flow value intervals from empirical distributions (D.labrax)

| Size (%) | 0-distribution | 1-distribution | 2-distribution | 3-distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | [0.00, 0.02] | [1.01, 1.02] | [2.00, 2.02] | [3.01, 3.03] |

| 10 | [0.00, 0.04] | [1.01, 1.03] | [2.00, 2.03] | [3.00, 3.04] |

| 25 | [0.00, 0.07] | [1.00, 1.04] | [1.97, 2.05] | [2.97, 3.07] |

| 50 | [0.00, 0.11] | [0.96, 1.07] | [1.93, 2.09] | [2.90, 3.12] |

| 75 | [0.00, 0.14] | [0.92, 1.12] | [1.86, 2.16] | [2.81, 3.20] |

| 90 | [0.00, 0.18] | [0.86, 1.18] | [1.78, 2.24] | [2.69, 3.30] |

| 95 | [0.00, 0.22] | [0.81, 1.23] | [1.72, 2.31] | [2.61, 3.39] |

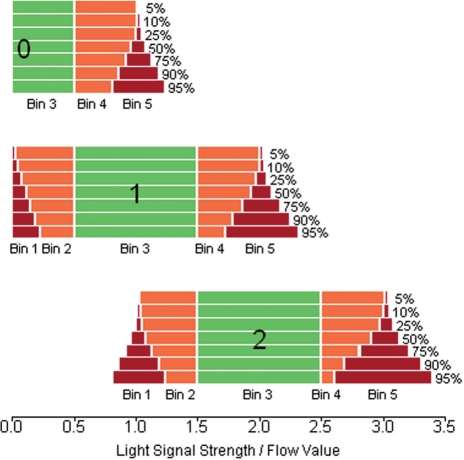

We constructed several series of intervals, containing from 5% (conservative) to 95% (liberal) of the flow values (Table 1 and Fig. 1). In order to decompose the distribution of flow values observed for homopolymers of length n, we assigned each associated flow value to one of several bins. First, flow values that would give a correct homopolymer length call (values between n −0.5 and n+0.49) were assigned into bin 3. Then, values that were likely to be associated with a neighboring peak at n −1 or n+1 (subpeaks in Figs 1 and 3) were assigned to bins 1 and 5, respectively (using the values from Table 1 as threshold values). Intermediate values were assigned into bins 2 and 4, while values outside the ranges of bins 1 and 5 were discarded (extreme under- or over-calls).

As an example, when considering a homopolymer of length 2, we would define our bins as follows (using the rather conservative 25% intervals, see Table 1 and Fig. 2): bin 3 contains correct base calls and is thus predefined as [1.5, 2.49]. All flow values that do not fall into this bin are counted as erroneous. Of all flow values in the range [0.5, 1.49], 25% are in [1.0, 1.04]. This interval thus defines bin 1 for homopolymer length 2. Flow values in this bin are assumed to originate from the 1-distribution and are thus—by our hypothesis—likely to be caused by PCR errors. Bin 5 is accordingly defined as [2.97, 3.07] and corresponds to PCR errors giving a triple homopolymer.

Fig. 2.

Bins for homopolymer lengths 0, 1 and 2, based on different flow value interval sizes from Table 1.

Furthermore, flow values that lie beyond bin 1 or 5 are counted as extreme miscalls of unknown origin (‘extreme errors’, see Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimated fraction of error types in percentage of overall errors

| Size (%) | Pyrosequencing errors (%) | Putative PCR errors (%) | Extreme errors (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 80.18 | 3.97 | 15.85 |

| 10 | 79.28 | 5.78 | 14.94 |

| 25 | 75.69 | 11.17 | 13.14 |

| 50 | 67.15 | 24.65 | 8.20 |

| 75 | 59.18 | 36.89 | 3.93 |

| 90 | 51.62 | 47.02 | 1.36 |

| 95 | 46.63 | 52.77 | 0.60 |

For each flow value together with the correct homopolymer length, we can now determine into which bin it falls. From the absolute counts, we can then for any sequence or set of sequences calculate the fraction of ‘putative PCR errors’ (Table 2), which is the sum of errors falling into bins 1 and 5 divided by the total number of erroneous base calls.

We used BLASTN (Altschul et al., 1990) to map 21 mate-pair runs from Gadus morhua (Atlantic cod) against the known mate-pair linker sequence (TCGTATAACTTCGTATAATGTATGCTATAC GAAGTTATTACG) and its reverse complement, assigning each flow value to the corresponding true homopolymer length as known from the linker sequence. This gave us a total of 17 834 274 reads, where 16 836 422 matched the linker sequence or its reverse complement (47% each) when a bit score cutoff of 67 was used. The 997 833 (6%) reads did not or not uniquely match either the linker or its reverse complement.

Further, we discarded 17% of the remaining reads because they had lost synchronism (Section 2.2) or were implausible, or did not match the linker over the whole length of 42 bp, which left us with a total of 14 050 646 complete matches.

From those reads, we examined the flow values for each of the 60 flows (15 flow cycles; 18 positions with negative flow values not leading to a base call; flows 1 and 60 were not counted in error calculations since they could be part of longer homopolymers) that were needed to sequence the 42 bp of the linker (Fig. 3). We assigned each flow value to one of the bins described above. From the total number of errors in each bin, we could calculate the percentage in relation to all observed errors (Table 2). In total, we observed a per-flow error rate of 0.153% (including negative flows), which is believed to underestimate the true error rate, first because we have filtered out bad alignments prior to our analysis, and also because the linker sequence only contains 1- and 2mers, and longer homopolymer runs are more likely to contain errors than shorter ones.

Even when using the conservative estimates, we get a fraction of 4–25% putative PCR errors in relation to all errors (Table 2).

This corroborates our theory that PCR errors might be an important error source in pyrosequencing. Notably, the fraction of PCR errors decreases with respect to the corresponding flow cycle in a read (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Putative PCR and pyrosequencing error rates with respect to flow cycles (for underlying flow value intervals of size 5 and 95%).

3 SIMULATING PYROSEQUENCING DATA

We have in our previous work (Balzer et al., 2010) presented flowsim, a simulation tool for 454 pyrosequencing data that uses empirical distributions of flow values to accurately model the pyrosequencing results and that provides the simulated data as SFF files.

3.1 The flowsim simulation pipeline

In order to extend flowsim and to take into account the various error types described above, the software is now split into several independent tools, each tool modeling a separate stage in the sequencing process.

The flowsim pipeline currently comprises the following utilities:

clonesim, which simulates shearing of an input genome according to a user-specified distribution of clone lengths.

gelfilter, which selects a subset of input clones according to a minimum and a maximum clone size.

duplicator, which introduces artificial duplicates of clones.

cr>kitsim, which attaches the end of the A-adaptor (which consists of the four letter ‘key’ at the beginning of reads, typically TCAG), and the B-adaptor.

cr>mutator, which mutates the input sequences with random insertions, deletions and substitutions at user-specified rates.

cr>flowsim, which simulates pyrosequencing of a set of input sequences, calculates quality scores, filters and quality-trims the reads, and outputs the resulting SFF file.

With the exception of flowsim which outputs an SFF file, all utilities work with Fasta sequences as input and output, and by default read from standard input and write to standard output. Thus, a simple command for creating 100 000 reads from an input genome, using default parameters, would be:

‘clonesim -c 100000 input.fasta | kitsim | flowsim -o out.sff’.

The separation into multiple programs provides more flexibility, and it is easy for users to implement and apply additional tools. For instance, a user could simulate amplicon sequencing by replacing clonesim with a program that simulates amplicons, and use the remaining flowsim pipeline to simulate the 454 sequencing process. Similarly, mate-pair libraries can be simulated by interposing a program that simulates circularization and fragmentation.

3.2 Simulation results

For simulation, we used a 764 Mb genomic scaffold from sea bass (D.labrax) generated from Sanger sequencing (Kuhl et al., 2010), where we also had available approximately 30× coverage 454 shotgun reads for comparison.

We used flowsim to simulate a high number of reads corresponding to 10× coverage, providing sufficient clone lengths for 800 flows (Titanium), using empirical distributions as flow model and quality degradation along the sequence, but only taking into account homopolymer length errors arising from the flow value distributions (i.e. we did not make use of kitsim or mutator). We assembled our simulated reads using Newbler beta version 2.5 (provided by Roche Diagnostics) and compared the assembly results, namely contig sizes, with the assembly of randomly chosen real D.labrax Titanium reads corresponding to equal coverage. Our assemblies of simulated reads were substantially better than those of real data in terms of contig sizes.

When carrying out earlier simulations from Escherichia coli (Balzer et al., 2010), we assumed strain-specific differences to be responsible for discrepancies between the assembly of real shotgun data and that of simulated data. Since we are now comparing reads that we simulated from the D.labrax reference scaffold with shotgun reads from the same individual, we can exclude this factor. Examining the simulation accuracy of flowsim, we identified the following factors to be potentially relevant for our assemblies having better statistics than the assemblies of real reads: coverage (average overall coverage, coverage distribution, zero-coverage regions), adaptors, putative PCR errors, pyrosequencing errors. Other errors, such as multiple DNA fragments associated with one bead, are likely to have been eliminated by the Roche quality-filtering.

In Section 2, we have examined each of these sources of variability and can make use of the updated flowsim pipeline described above for further simulations.

After having added errors to the same simulated clones that we used in earlier assemblies, i.e. first attaching adaptor sequences and subsequently introducing PCR noise at rates comparable with those found in real shotgun data, we ran flowsim and performed a new assembly of our simulated reads. It still outperforms an assembly of real reads, but assembly statistics like contig sizes and the percentage of aligned reads and bases are closer to the assembly of real reads when simulating additional error sources. We will also more closely examine to what extent the real pyrosequencing D.labrax data contain heterozygosity (coming from a diploid fish) and how a similar effect can be introduced into the simulated reads.

While the current version of our simulator uses a uniform coverage distribution over the input genome, we assume that this approach is not sufficiently realistic. Typically, there is greater than a 100-fold variation in coverage (Harismendy et al., 2009). This is in agreement with our data, finding per-base coverage up to 760 in D.labrax (average 33) and 1152 in E.coli (average 110).

Using cd-hit-454 (Niu et al., 2010), we observed duplicate read rates between 2.73 and 19.13% for D.labrax and between 0.19 and 10.71% for E.coli, with 98–100% sequence identity, while—as expected—our simulated reads (D.labrax, 10−30× coverage) only contained very few (0.01%) duplicates or almost-duplicates.

4 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we have explored different error sources of 454 pyrosequencing. Previously, light signal distributions from the pyrosequencing chemistry and carry-forward/incomplete extension have been seen as the major sources of noise. Neighboring peaks in flow value distributions, observed in earlier analyses when aligning reads to a reference, were believed to arise from biological differences between reads and reference, but by matching reads against a known mate-pair linker sequence and only using these short alignments for our analyses, we eliminate this source of error. We speculate that, beside pyrosequencing errors due to inaccuracies in the sequencing process, also errors from the PCR library preparation step could account for a high percentage of observed errors. Hence, we present an empirical approach to support our assumptions, based on the presence of strong neighboring peaks in the distributions of flow values that correspond to the linker sequence. We see a clear decrease in the proportion of errors assigned to neighboring peaks as we move towards the end of the read, which is most likely due to the increase in pyrosequencing errors caused by widening flow value distributions. This implies that neighboring peak errors occur at an approximately constant rate along the read.

Furthermore, it is difficult to see how the neighboring peaks could arise from known error sources. Random noise in flow values should result in distributions similar to Gaussian, and we see no reason for CAFIE errors to concentrate around integral values. Thus, we believe that the neighboring peaks are caused by real differences in the library clones, but we cannot currently suggest an explanation on how these arise.

Finally, our new additions to the simulation pipeline enable us to simulate many of the identified errors, and we see that the resulting assemblies are approaching those obtained from real data. Nevertheless, we are examining further factors that we believe to be relevant in read simulation and quality assessment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Dr Richard Reinhardt, Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics, Berlin, and Dr Kjetill Jakobsen, University of Oslo, and the Cod Genome Project team for kindly providing us with Titanium raw data. We also would like to acknowledge Anders Lanzén, University of Bergen, Dr Niina Haiminen, IBM T.J. Watson Research Center, Dr Christopher Quince, University of Glasgow and Markus Grohme, TH Wildau, for the fruitful discussions and assistance in analyses.

Funding: National Program for Research in Functional Genomics in Norway (FUGE) in the Research Council of Norway.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Altschul S.F., et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzer S., et al. Characteristics of 454 pyrosequencing data–enabling realistic simulation with flowsim. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:i420–i425. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou H.H., Holmes M.H. DNA sequence quality trimming and vector removal. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1093–1104. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Alvarez V., et al. Systematic artifacts in metagenomes from complex microbial communities. ISME J. 2009;3:1314–1317. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harismendy O., et al. Evaluation of next generation sequencing platforms for population targeted sequencing studies. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R32. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff K.J. The effect of sequencing errors on metagenomic gene prediction. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:520. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse S.M., et al. Accuracy and quality of massively parallel DNA pyrosequencing. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R143. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl H., et al. The European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax genome puzzle: comparative BAC-mapping and low coverage shotgun sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin V., et al. Wrinkles in the rare biosphere: pyrosequencing errors can lead to artificial inflation of diversity estimates. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;12:118–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies M., et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu B., et al. Artificial and natural duplicates in pyrosequencing reads of metagenomic data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:187. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quince C., et al. Accurate determination of microbial diversity from 454 pyrosequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:639–641. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quince C., et al. Removing noise from pyrosequenced amplicons. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan A.R., et al. Pyrobayes: an improved base caller for SNP discovery in pyrosequences. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:179–181. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche Applied Science (2008) Genome Sequencer Data Analysis Software Manual, Software Version 2.0.00, Roche Diagnostics GmbH.