Abstract

Motivation: Cryo electron tomography (CryoET) produces 3D density maps of biological specimen in its near native states. Applied to small cells, cryoET produces 3D snapshots of the cellular distributions of large complexes. However, retrieving this information is non-trivial due to the low resolution and low signal-to-noise ratio in tomograms. Current pattern recognition methods identify complexes by matching known structures to the cryo electron tomogram. However, so far only a small fraction of all protein complexes have been structurally resolved. It is, therefore, of great importance to develop template-free methods for the discovery of previously unknown protein complexes in cryo electron tomograms.

Results: Here, we have developed an inference method for the template-free discovery of frequently occurring protein complexes in cryo electron tomograms. We provide a first proof-of-principle of the approach and assess its applicability using realistically simulated tomograms, allowing for the inclusion of noise and distortions due to missing wedge and electron optical factors. Our method is a step toward the template-free discovery of the shapes, abundance and spatial distributions of previously unknown macromolecular complexes in whole cell tomograms.

Contact: alber@usc.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cryo electron tomography (cryoET) enables the 3D visualization of a cell's interior under close to live conditions (Best et al., 2007; Frank, 2006; Lučić et al., 2005; Medalia et al., 2002; Murphy and Jensen, 2007). Such tomograms are essentially 3D representations of the entire proteome providing a snapshot of the distributions of protein complexes and their interaction networks (Alber et al., 2008; Beck et al., 2011). However, retrieving shape information and distributions of macromolecular assemblies is not trivial due to the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), missing data and non-isotropic resolution, and the fact that individual macromolecules are difficult to recognize in a highly crowded environment (Best et al., 2007; Böhm et al., 2000; Frangakis et al., 2002; Medalia et al., 2002). So far, the identification of macromolecular complexes is accomplished mostly by template matching methods (Best et al., 2007; Böhm et al., 2000; Frangakis et al., 2002; Medalia et al., 2002). where the signals representing the density map of a known protein complex structure are correlated to the signals in the cryoET map. The cross-correlation between the template and tomogram is calculated for each position and every possible orientation. Peaks in the resulting cross-correlation function across the whole tomogram may indicate positions occupied by the particular complex. A major drawback, however, is that template matching cannot discover yet structurally unknown complexes. So far only a relatively small fraction of large protein complexes have been structurally resolved. Furthermore, recent work has shown that the quaternary structure of large protein complexes varies considerably across different organisms (Han et al., 2009) and available reference structures might therefore not be applicable to the desired organism. Even if a template structure is available, the template-based methods may fail if the template structure is in a different conformation or is bound to additional proteins than the target complexes in the tomogram. As a consequence, template-based methods may fail in detecting an unbiased atlas of the spatial arrangement of all complexes in a cell (i.e. a cellular proteome ‘atlas’). It is, therefore, of great importance to develop template-free methods for the detection of macromolecular complexes in cryo electron tomograms. Such methods will allow not only the discovery of the shapes of unknown macromolecular complexes but also allow detecting their positions and orientations in the cryo electron tomograms.

The key problem in a template-free approach is to identify frequently occurring density patterns in cryo electron tomograms. A pattern is defined by voxel regions with similar intensity structures, which appear multiple times at different position in the tomogram. Such frequently occurring patterns represent objects of biological interest. In this article, we focus on patterns that correspond to protein complexes. Once identical complexes are discovered, their subtomograms can be locally aligned and their density distribution averaged producing a density map of the complex with improved SNR.

Identifying recurrent patterns in cryo electron tomograms is challenging because neither the composition nor the total number of the patterns is known. Moreover, cryo electron tomograms are of very low resolution (≥4 nm), low SNR and are subject to distortions due to electron optical effects. Therefore, traditional methods in computer vision derived for high resolution and high SNR 3D object recognition usually cannot be directly applied to cryo electron tomograms (Tangelder and Veltkamp, 2008).

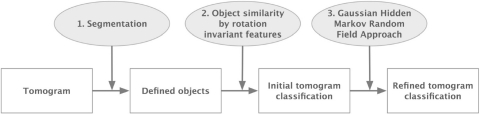

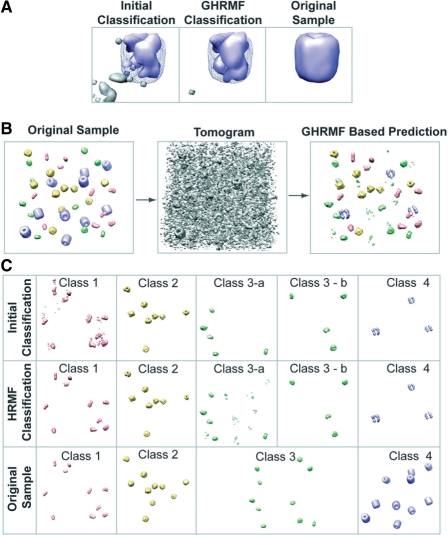

Here, we propose a step-wise approach for classifying cryo electron tomograms into recurrent density patterns (Fig. 1). First, an initial classification is generated based on rotation-invariant features of the tomogram. In the second step, this initial classification is refined using a Gaussian Hidden Markov Random Field (GHMRF) model. As an inference method, GHMRF models have shown robustness in 2D image segmentations at relatively high noise levels (Zhang et al., 2001). Here, we extend the GHMRF framework to the classification of recurrent patterns in 3D cryoET maps, which contain high levels of noise and distortions.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of our protocol.

In this article, we provide the first proof of principle of the method, and demonstrate its applicability for the detection of frequently occurring protein complexes in noisy density maps with relatively high accuracy. We test our approach on realistically simulated cryo electron tomograms including low resolution, high levels of noise and distortions due to missing wedge effects and electron optical factors.

2 METHODS

Our method consists of three steps (Fig. 1): first, we identify candidate patterns (i.e. objects) by segmenting the tomogram into high intensity regions. This step reduces the search space to the most promising density regions. Second, the similarity between all the objects is compared. To calculate similarities between all the objects efficiently, each tomogram voxel (i.e. the 3D equivalent of an image pixel) is represented by a feature vector that describes the local intensity distribution in the proximity of the voxel in a rotationally invariant manner. The similarity between objects is then determined efficiently by comparing the distances between the corresponding feature vectors. Then the segmented objects are clustered based on their feature vector similarity. All voxels in objects of the same cluster are assigned to the same pattern class. Third, the resulting initial voxel classification is refined by an GHMRF approach. The GHMRF approach reclassifies the voxels into recurrent patterns by maximizing the probability to observe the classification for the given tomogram.

2.1 Problem formulation and definitions

A tomogram is described by a 3D grid of voxels that are associated with values of electron optical density. Let 𝒯={1,2,…,N} be the set of indices of all voxels in the density map, and let xi∈ℝ3 be the location of voxel i∈𝒯 in the map.

Intensity vector: then, a tomogram is represented by a N-dimensional vector of the ordered list of intensity values for all voxels.

| (1) |

where N is the total number of voxels and fi is the intensity value of voxel i.

Class label vector: a pattern in a density map is defined as a collection of voxels that may have different intensities but are assigned to the same pattern class. Let us define the set of all pattern classes in a tomogram as 𝒞={1,2,…,C}, with C as the total number of classes. Each voxel in the density map can be assigned to one of the classes in 𝒞. Similar to an intensity vector, we therefore define a class label vector

| (2) |

where li∈𝒞 is the class label of voxel i. Whereas the intensity vector f is known, the class label vector l is unknown and to be inferred. The task of identifying recurrent patterns in a density map is therefore equivalent to determining the class label vector l∈ℒ. To achieve this goal, we apply a two-step procedure, combining a heuristic approach generating an initial tomogram classification with a subsequent refinement using a statistical inference method that maximizes the joint probability of the class assignment l and the intensity f.

2.2 Initial tomogram classification

The goal of the following section is to define an initial class label vector l, which serves in a later step as an input in the GHMRF-based refinement process.

2.2.1 Identification of segmented objects.

First, Gaussian filtering is applied to generate a blurred density map fblur reducing the influence of noise in the segmentation. Then a seed growth approach is adapted from the watershed segmentation (Dougherty, 1993) as follows. All local intensity maxima in the filtered map are identified. Local maxima with low intensity values are likely a result of noise and are discarded. The remaining local maxima with high intensity voxels are used as seeds for an extended watershed segmentation procedure. During the seed growth segmentation, a voxel rank r is introduced that captures the order at which voxels are included to a region. A segmented region Ss is defined, where the watershed algorithm is terminated at a given voxel rank rsmax. Let vs,r be a specific voxel index, of segment s and voxel rank r, then the set of voxels in a region of segmented object Ss is defined as

| (3) |

such that  for all s. Note that the filtered tomogram is only used to identify the indices of voxels in the segmented objects. Classifications are performed using the unfiltered intensity values of these voxels.

for all s. Note that the filtered tomogram is only used to identify the indices of voxels in the segmented objects. Classifications are performed using the unfiltered intensity values of these voxels.

2.2.2 Rotation-invariant feature vectors.

To introduce an efficient way to compare the similarities between all the distinct objects, we introduce rotation-invariant feature vectors (Kazhdan et al., 2003; Saha et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2009).

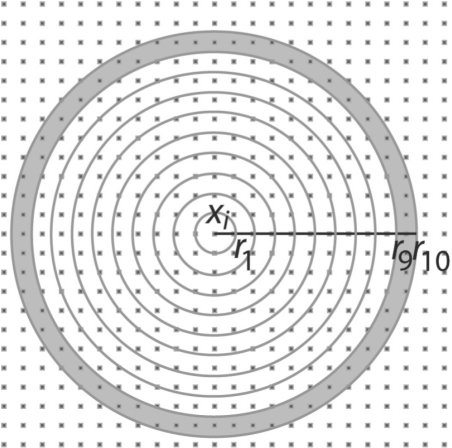

Rotation-invariant feature vectors p(xi) describe the intensity distribution of the tomogram in the neighborhood of a voxel located at xi. To construct a feature vector at the voxel location xi, we divide the neighborhood of the voxel xi into M concentric shells (Fig. 2)

| (4) |

where Vj(xi) is defined as the set of voxels that fall into the concentric shell centered at xi and is defined by the two radii rj−1 and rj, where with rj=jR/M and R is the largest chosen radius. If a concentric shell Vj(xi) is thin (i.e. rj+1−rj≈ voxel length), then the voxel intensities f(xk) with k∈Vj(xi) can be approximated by a spherical function g that is defined on the surface of a sphere in spherical coordinates.

| (5) |

where  , and θ, ϕ are the colatitude and longitude angles, respectively. g can then be approximated by a sum of its spherical harmonics (Hobson, 1931):

, and θ, ϕ are the colatitude and longitude angles, respectively. g can then be approximated by a sum of its spherical harmonics (Hobson, 1931):

| (6) |

where L is a given bandwidth, and alm is a coefficient associated with the complex spherical harmonics function Ylm, which is independent to g.

Fig. 2.

Neighborhood volumes defined as a series of concentric shells around voxel location xi for voxel i∈𝒯. Schematic view of a 2D grid with individual voxels shown as dark grey dots. Concentric shells are constructed that are centered at xi. The largest radius is defined as R. All radii are defined as rj=jR/M, with M as the maximal number of shells. A neighborhood volume Vj(xi)={k∈𝒯:rj−1<|xk−xi|≤rj} is defined as all voxels that fall into a concentric shell defined by two radii, rj−1 and rj with rj−1<rj. As an example, the neighborhood shell V10(xi) is shown in light grey, defined as the set of voxels located between radii r9 and r10.

Based on such a decomposition, the intensity distribution of all the voxels in shell Vj(xi) can then be described by a set of L rotation-invariant features {sjl|l=1,…,L}(Kazhdan et al., 2003) as follows:

| (7) |

Such features are calculated for all the M shells. The rotation-invariant description of the density distribution around the location of a voxel xi is then defined by the following feature vector:

| (8) |

whose elements consist of the ordered sequence of sjl for all consecutive shells {Vj(xi)|:j=1,…,M}. These feature vectors are rotation invariant, which means that they are independent of the relative orientation of the local density distribution. Therefore, feature vector-based similarities between density regions can be calculated even if these regions are at different relative orientations to each other. Previously, we have shown that such rotational invariant features are also robust against noise in maps (Xu et al., 2009).

2.2.3 Comparing the similarity of segmented objects.

The goal is to cluster segmented objects based on their feature vector dissimilarity. The dissimilarity oa,b between objects a and b is defined as one minus the fraction of voxels with similar feature vectors in both objects Sa and Sb.

| (9) |

where  is the number of similar feature vectors that appear both in objects Sa and Sb.

is the number of similar feature vectors that appear both in objects Sa and Sb.

| (10) |

𝒩ifea is the set of feature vectors that are most similar to feature vector i, but are located spatially apart from i in the tomogram.  and

and  are the total number of feature vectors in Sa and Sb, respectively.

are the total number of feature vectors in Sa and Sb, respectively.  is the sum of the total number of feature vectors in object a for which a similar feature vector exists in object b and the number of feature vectors in b with a similar feature vector in a.

is the sum of the total number of feature vectors in object a for which a similar feature vector exists in object b and the number of feature vectors in b with a similar feature vector in a.

To determine 𝒩ifea, the voxels in the tomogram are clustered based on the Euclidian distance between their feature vectors. Cryo electron tomograms are generally so large that not all feature vectors can be stored in computer memory at the same time. We, therefore, employ a large-scale clustering technique, (BIRCH) (Harrington and Salibián-Barrera, 2008; Zhang et al., 1997). The clustering cutoff is chosen heuristically by sampling the similarities between randomly selected feature vectors. Good performances have been achieved when the cutoff comprises the top 5% of sampled feature vector similarities. Then all voxels are detected that are in the same cluster but are apart in grid space so that they are not direct neighbors in the tomogram. For each voxel i in each cluster A a voxel set is defined as Ui={k:|xk−xi|>rd,k∈A}, where rd is a predefined grid distance.

It is computationally beneficial to restrict 𝒩feai to only a fixed number of the closest voxel neighbors. Here, 𝒩feai is defined as the subset of Ui with the 20 voxels whose feature vectors are most similar to the feature vector of i. Slight variations of this number do not affect the outcome of our calculations.

2.2.4 Clustering of segmented objects.

Next, all segmented objects are clustered using hierarchical clustering with the dissimilarity measure oa,b. The clustering cutoff is determined as the global minimum in a penalty function that seeks to simultaneously minimize the number of clusters and the variation within each cluster according to Kelley et al., (1996). All objects in the same cluster define the same frequently occurring density pattern. Because we are only interested in frequently occurring patterns clusters with less than three objects are discarded. The number of all density pattern classes C is then defined as the number of all clusters n and a ‘background’ class, which comprises all the voxels in the tomogram that are not part of any segmented object. All the voxels in objects that are part of the same cluster are assigned to the same class label l∈𝒞, with 𝒞={1,2,…,n}. All remaining voxels in the tomogram are assigned to the background class.

The assignment of all the voxels to the pattern classes defines the class label vector l=(l1,…,lN), which is the initial classification of the tomogram and serves as input information for a refined reclassification described in the following section.

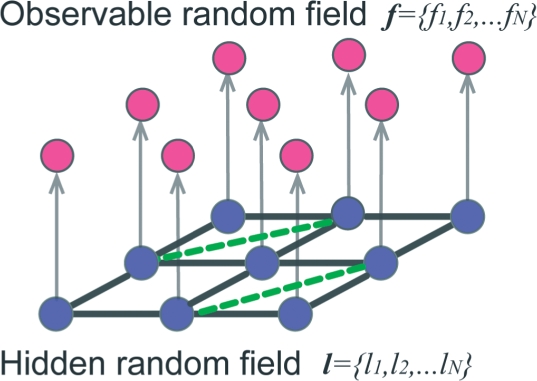

2.3 Classification refinement by Gaussian Hidden Markov Random Field Model

In this section, the initial classification is refined using an GHMRF model. In the GHMRF framework, class labels are not directly observable variables and are modeled as a hidden random field. The class labels are determined by maximizing the joint probability P(l,f) of class labels l and the intensity vector f. GHMRF has been used for image analysis and segmentation (Li et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2001). Here, we apply and extend the method to 3D density maps for the classification of frequently occurring macromolecular complexes in cryo electron tomograms.

2.3.1 Gaussian Hidden Markov Random Field Model.

In the GHMRF framework, the voxel labels are modeled as a hidden random field. Their conditional independence follows the Markov property and can be described by an undirected graph where each node corresponds to a voxel.

| (11) |

where l𝒩i={lj|∀j∈𝒩i} are the labels of neighbor voxels of i.

In standard GHMRF models, the voxel neighborhood is defined by an undirected graph with voxels as vertices and edges as the cubic grid connecting the vertices (Fig. 3). In our method, this graph is augmented by additional edges between those voxels that share similar feature vectors but are at far distance in the tomogram grid. In other words, for a given voxel i, its neighborhood list 𝒩i includes all direct grid neighbors in the tomogram and all voxels that have a similar density environment even if they are located at far distance (Fig. 3). By augmenting the list of grid neighbors, we are able to connect those voxels in the graph that have the same class label, even if these voxels are part of different copies of the same complex located at different regions of the tomogram. The neighborhood 𝒩i of voxel i is, therefore, defined as

| (12) |

where 𝒩mapi is the set of all voxels that are adjacent to i in the tomogram grid and 𝒩feai is the set of voxels that have similar feature vectors.

Fig. 3.

Gaussian Hidden Markov Random Field. GHMRF with observable intensity random field (above in red) and hidden class random field (below in blue). In the hidden field, the Markov property graph is defined by the direct neighbors of voxels in the grid (grey connections, for simplicity only a 2D grid is shown) and also by voxels with similar feature vectors (green dotted connections) (i.e. a green connection is formed if two voxels are defined as neighbors in the feature space).

Voxel intensities fi form an observable random field. Given the class label li=l, the voxel intensity fi is assumed to follow a conditional probability distribution

| (13) |

where Φ(f;μl,σl) denotes Gaussian distribution with mean μl and SD σl that are specific to class label l. In addition, given one instance of l, the intensities f are assumed to be conditionally independent.

| (14) |

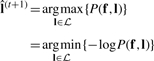

2.3.2 Iterative optimization method for voxel classification.

The voxel re-classification is formulated as a maximization problem:

| (15) |

is the best estimation for the true class label vector. P(f,l) is the joint probability of the intensities f and class labels l, where θ={μl,σl} is the collection of mean and SD parameters for the intensity values of the voxels in each of the pattern classes. To perform the maximization, we use an iterative approach (Zhang et al., 2001) that consists of two steps. First, for a given estimation of the parameter set

is the best estimation for the true class label vector. P(f,l) is the joint probability of the intensities f and class labels l, where θ={μl,σl} is the collection of mean and SD parameters for the intensity values of the voxels in each of the pattern classes. To perform the maximization, we use an iterative approach (Zhang et al., 2001) that consists of two steps. First, for a given estimation of the parameter set  at iteration t, a classification is performed to obtain updated class labels

at iteration t, a classification is performed to obtain updated class labels  . Then expectation maximization determines the optimal parameter set

. Then expectation maximization determines the optimal parameter set  given

given  obtained from the first step.

obtained from the first step.

Step 1: classification.

Given  , we want to obtain

, we want to obtain

|

(16) |

According to (Zhang et al. (2001), the minimization problem can be formulated as

| (17) |

with the energy functions

| (18) |

and

| (19) |

where κ is the set of all cliques on the graph. Following Zhang et al. (2001), we choose Vc=−δlilj, where δ is the Kronecker delta function. Calculating the global minimum of Equation (17) is computationally infeasible. However, because both U(f|l) and U(l) can be expanded into sums over all voxels i∈𝒯, the optimal solution can be approximated using the iterated conditional modes (ICM) algorithm (Besag, 1986), which is popular in solving such optimization problems. This method optimizes U(li|l𝒯∖{i},f) for each i∈𝒯, while keeping all other labels l𝒯∖{i} fixed.

Step 2: Expectation maximization for model fitting.

The expectation maximization method updates parameters θ by maximizing the conditional expectation

| (20) |

Following Zhang et al. (2001), new parameters are estimated as

| (21) |

and

| (22) |

where

| (23) |

Following Li (2009) and given the class labels l𝒩i obtained from the classification step, the probability for a voxel i to be assigned to class label l is calculated as

| (24) |

The iterations between expectation and maximization step are repeated until convergence is reached, leading to the newly refined class label vector l.

Finally, a class label can be defined for each object as the label that is assigned to the majority of voxels in the object. The classification performance is increased, if all the voxels with labels different to the corresponding object label are reassigned to the background class.

2.4 Generating simulated cryo electron tomograms

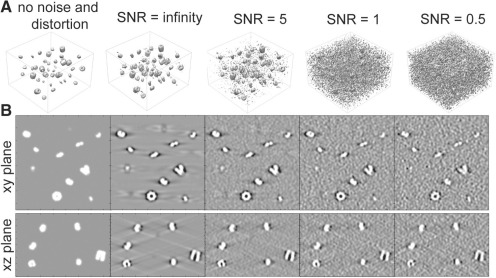

For a reliable assessment of the method, tomograms must be generated by simulating the actual tomographic image reconstruction process, allowing the inclusion of noise, tomographic distortions due to missing wedge and electron optical factors such as contrast transfer function (CTF) and Modulation Transfer Function (MTF) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Simulated electron tomograms including missing wedge effects, CTF and MTF for a tomogram at different SNR levels. (A) Contour volume representation of the tomogram and (B) a slice through x–y plane of the tomogram (top panel) and a slice through the x–z plane of the tomogram (bottom panel).

We follow a previously applied methodology for simulating the tomographic image formation mechanism as realistically as possible (Beck et al., 2009; Förster et al., 2008; Nickell et al., 2005). The electron optical density of a macromolecule is proportional to its electrostatic potential and the density map can be calculated from the atomic structure by applying a low pass filter at a given resolution. Here, density maps are generated at 4 nm resolution using the PDB2VOL program of the Situs 2.0 package (Wriggers et al., 1999) with voxel length of 1 nm. These initial density maps are then used as samples for simulating electron micrograph images at different tilt angles. In cryoET, the sample is tilted in small increments around a single-axis. At each tilt angle, a simulated micrograph is generated from the sample. We set the tilt angle rotating from −70 to 70○ with steps of 2○, which is a typical procedure for experimental tomograms. As a result, our data contains a wedge-shaped region in Fourier space for which no data have been measured (missing wedge effects), similar to experimental measurements. The missing wedge effect leads to distortions of the density maps along the tilt-axis. To generate realistic micrographs, noise is added to the images and the resulting image map is convoluted with a CTF, which describes the imaging in the transmission electron microscope in a linear approximation. Any negative contrast values beyond the 1st zero of the CTF are eliminated. We also consider the MTF of a typical detector used in whole cell tomography, and convolute the density map with the corresponding MTF. The CTF and MTF describe distortions from interactions between electrons and the specimen and distortions due to the image detector (Frank, 2006; Nickell et al., 2005). Typical acquisition parameters that were also used during actual experimental measurements of whole cell tomograms (Beck et al., 2009) were used: voxel grid length=1 nm, the spherical aberration=2×10−3 m, the defocus value=−4×10−6m, the voltage=200 kV, the MTF corresponded to a realistic electron detector (McMullan et al., 2009), defined as sinc(πω/2) where ω is the fraction of the Nyquist frequency.

Finally, we use a backprojection algorithm to generate a tomogram from the individual 2D micrographs that were generated at the various tilt angles (Beck et al., 2009). To test the influence of increasing noise, we add different amount of noise to the images, so that the SNR levels range between 5 and 0.5, respectively (Fig. 4).

2.5 Benchmark set

The classification is tested on simulated tomograms containing 40 complexes of four different classes (Fig. 4). To assess bias arising from specific combinations of complexes, a set of 24 types of complexes of variable sizes were selected from the PDB databank (Fig. 5). From this pool, 52 benchmark sets were generated that each contained four randomly chosen types of complexes. To generate a tomogram for each of these combinations, 10 instances of each complex were randomly oriented and placed into a grid of size 150 nm×150 nm×100 nm (Fig. 4). For two of the 52 benchmark sets (set 1 and set 2), 50 independent density maps were generated each with randomly placed complexes. For each density map, a tomogram was simulated at four different signal-to-noise ratios (SNR=0.5, 0.1, 5, ∞) (Fig. 4) leading to a total of 200 simulated tomograms per set. Set 1 contains GroEL [1KP8], heat-shock protein ACR1 [2BYU], carboxipeptidase [2BO9] and propionyl-CoA carboxylase [1VRG] (PDB ID in squared brackets). Set 2 contains ornithine carbamoyltransferase [1A1S], octomeric enolase[1W6T], RNA polymerase [2GHO] and ClpP [1YG6]). For the remaining 50 benchmark sets of complexes, tomograms were generated at SNR=0.5.

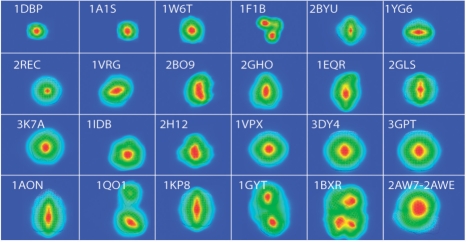

Fig. 5.

Average minimum feature vector distance maps. Contour level plot of the average minumum feature vector distance maps for 24 complexes. The value assigned to each grid voxel in a map is the average minimum distance between its feature vector and the feature vectors in the density maps of all the other complexes. The contour plane contains the maximal value. Colors are based on a rainbow scheme with red as the maximum and blue as the minimum values. The PDB ID of each complex structure is also shown.

2.6 Analysis

For the simulated tomograms, l is compared to the known ground truth ltrue. A true positive match is defined when a voxel's predicted class label li is identical to the true class label litrue. To assess the performance, the precision and recall of the classification is calculated. The precision is a measure of exactness defined as the fraction of the correctly predicted voxels,

| (25) |

where #TP is the number of true positives and #TP+#FP is the total number of voxels with the same class labels. The recall is a measure of completeness defined as the number of true positives divided by the total number of voxels of that class in the ground truth.

| (26) |

where #FN is the number of false negatives, i.e. the number of voxels that were not identified as class members. In addition, the precision and recall for classifying segmented objects is calculated. Here, class labels are defined for complexes (i.e., segmented objects) instead of individual voxels.

3 RESULTS

First, we analyze the effectiveness of the rotation-invariant feature vectors in detecting pattern similarities in a tomogram. Then we describe the performances of the initial pattern classification and the refined pattern classification based on the GHMRF approach.

3.1 Analysis of feature vectors

We now determine the locations of the most unique feature vectors in a complex. For each of the 24 benchmark complexes, a simulated density map is generated at 4 nm resolution (Wriggers et al., 1999) and its rotation-invariant feature vectors are calculated. For each voxel in a complex, the distance is calculated between its feature vector and all the feature vectors in the other complexes. For each of the 24 complexes, the minimum distance is determined. For the given voxel, the average of all minimum distances is a measure of the feature vector's uniqueness with respect to the feature vectors in all the other complexes. The average minimum distance correlates strongly with the position of the voxel from the mass center of the complex (average Pearson's correlation −0.68±0.05). Voxels at the complex center have feature vectors that are most different from those in other complexes and are therefore most discriminative for classification purposes (Fig. 5). Moreover, larger complexes have generally a greater number of unique feature vectors (Fig. 5). These findings provide an important guide for increasing accuracy and computational efficiency of the method. Instead of processing all feature vectors in a tomogram, one should focus only on those vectors that are located at the central regions of a complex. Considering only the most informative feature vectors will not only increase the accuracy of the method but also greatly increase the computational efficiency and reduce the necessary computational memory consumption. Noise and distortions in a map will reduce the number of unique feature vectors, however, also then the central regions are most discriminative for classification. Accordingly, the similarity between the segmented objects in a tomogram is calculated by using only its central core regions.

3.2 Parameter definition

The classification accuracy is increased, if the similarity between segmented objects is calculated from their core regions. Here, the core region is set to be 500 nm3 and is defined by the termination of the adapted watershed algorithm after 500 voxels are selected: Sscore={vs,r|r=1,…,rsmax=500}. The good performance for using a fixed rather than a relative sized core region is presumably a result of the limited size range of soluble complexes in a cell, which ranges typically up to ≈2700 nm3 (ribosome) with a mean of ≈656 nm3 in our sample. A slight variation of the core region size does not change the outcome of our analysis. However, using more extended regions will not improve but often decrease the classification accuracy while reducing computational efficiency significantly.

While the object similarities are determined from the core regions (Score), the determined class labels are assigned to all voxels in an extended region Ssext={vs,r|r=1,…,rsmax=2000}.

3.3 Classification performance

We now analyze the performance of the method and distinguish between the assessment of individual voxels and segmented objects. In addition, the performance is analyzed with respect to different combinations of complex types and their relative placements in the tomograms.

3.3.1 Voxel-based classification.

To compare the influence of noise, we have generated 50 tomograms for four different SNR levels (Tables 1 and 2). For benchmark set 1, the average precision of the initial classification is 0.44 with an average recall of 0.54 for tomograms without noise. With increasing noise levels, the performance reduces to 0.39 and 0.5 for the precision and recall, respectively. As expected, the GHMRF model improves significantly the precision and recall. For tomograms with the highest noise level, the average precision is improved from 0.39 to 0.44 in comparison to the initial classification (Table 1 and Fig. 6). These observations indicate that about 40% of all voxels can be predicted as members of the correct pattern class, even when significant noise and distortions are present in the tomogram. This excellent performance is in a similar range as classifications based on template matching.

Table 1.

Voxel-and object-based classifications of benchmark set 1 for tomograms at four different SNR levels

| Initial |

GHMRF |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNR | Precision | Recall | Precision | Recall |

| Voxel-based classification | ||||

| ∞ | 0.44 (0.07) | 0.54 (0.07) | 0.54 (0.10) | 0.60 (0.10) |

| 5 | 0.43 (0.07) | 0.53 (0.08) | 0.58 (0.10) | 0.63 (0.11) |

| 1 | 0.42 (0.08) | 0.52 (0.09) | 0.55 (0.09) | 0.60 (0.10) |

| 0.5 | 0.39 (0.08) | 0.50 (0.08) | 0.44 (0.10) | 0.50 (0.10) |

| Object-based classification | ||||

| ∞ | 0.68 (0.09) | 0.68 (0.09) | 0.76 (0.10) | 0.76 (0.10) |

| 5 | 0.67 (0.12) | 0.67 (0.12) | 0.76 (0.13) | 0.76 (0.13) |

| 1 | 0.68 (0.13) | 0.68 (0.13) | 0.77 (0.13) | 0.77 (0.13) |

| 0.5 | 0.65 (0.11) | 0.65 (0.11) | 0.71 (0.10) | 0.71 (0.10) |

For each SNR level, 50 tomograms are generated. Each tomogram consists of 40 complexes of four different types. Values are the mean precision and recall for the set of 50 classifications with standard deviations (SDs) shown in brackets.

Table 2.

Voxel-and object-based classifications of benchmark set 2 for tomograms at four different SNR levels

| Initial |

GHMRF |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNR | Precision | Recall | Precision | Recall |

| Voxel-based classification | ||||

| ∞ | 0.50 (0.16) | 0.72 (0.17) | 0.72 (0.14) | 0.84 (0.16) |

| 5 | 0.45 (0.18) | 0.68 (0.19) | 0.72 (0.18) | 0.79 (0.20) |

| 1 | 0.30 (0.18) | 0.53 (0.18) | 0.52 (0.21) | 0.57 (0.22) |

| 0.5 | 0.31 (0.15) | 0.54 (0.16) | 0.51 (0.19) | 0.56 (0.20) |

| Object-based classification | ||||

| ∞ | 0.85 (0.19) | 0.85 (0.19) | 0.91 (0.12) | 0.91 (0.12) |

| 5 | 0.79 (0.22) | 0.80 (0.22) | 0.87 (0.15) | 0.87 (0.15) |

| 1 | 0.61 (0.23) | 0.61 (0.23) | 0.70 (0.17) | 0.71 (0.17) |

| 0.5 | 0.58 (0.20) | 0.59 (0.20) | 0.64 (0.16) | 0.65 (0.16) |

For each SNR level, 50 tomograms are generated. Each tomogram consists of 40 complexes of four different types. Values are the mean precision and recall for the set of 50 classifications with SDs shown in brackets.

Fig. 6.

(A) (Left panel) Initial classification for a density region that contains a proteasome complex (blue color). It is evident that the proximity of the complex contains voxels that are false classified as being part of another complex class (grey color). (Middle panel) After GHMRF-based refinement, most of the voxels assigned to the second complex class have been removed. (Right panel) Original density map of the proteasome complex at 4 nm resolution, shown without noise, missing wedge, CTF and MTF distortions. (B) Classification for a tomogram of set 1: left panel shows the initial density map of the sample collection of four different types of complexes, each with 10 copies. (middle panel) Based on this sample a tomogram is simulated with an SNR of 0.5. (Right panel) The GHMRF-based classification discovers several sets of recurrent density patterns that represent the different complexes in the sample. (C) (Top panel) The initial classification discovers five different classes of patterns, each containing several instances. (Middle panel) The GHMRF-based reclassification improves the predictions considerably. (Lower panel) The four different classes of complexes in the initial dataset. It is evident that complexes in class 3 have been divided into two classes in the GHMRF-based classification. However, all complexes classified to the same class are identical. (The selected example shows an average classification performance.)

For benchmark set 2, precision and recall for the initial classification is substantially higher for tomograms with low noise levels in comparison to set 1. However, the initial classification is more affected by noise in the tomogram in comparison to benchmark set 1. The differences in performance presumably reflect the variable number of unique feature vectors in different complexes. The average precision decreases from 0.5 for tomograms without noise to 0.31 for tomograms with an SNR level of 0.5 (Table 2). Again, the GHMRF model improves the performance dramatically, in particular for tomograms with high noise levels. For tomograms with the highest noise level, the precision is improved from 0.31 to 0.51 in comparison to the initial classification (Tables 1 and 2). As a statistical inference method the GHMRF-based refinement appears more robust against the distortions in the tomogram due to missing wedge, electron optical factors and increasing noise levels.

To further test different combinations of complexes, 50 additional sets of randomly chosen complexes were tested. For all of these sets, tomograms were generated with SNR of 0.5. The average precisions, recall and their SDs are very similar to those of sets 1 and 2 [voxel-based GHMRF classification, averaged over all sets: precision 0.45 (0.12), recall 0.51 (0.12); object-based GHMRF classification: precision 0.62 (0.14), recall 0.62 (0.14)] (Supplementary Table S1).

3.3.2 Object-based classification

Assessment of the classification can also be performed based on segmented objects rather than individual voxels. A true positive match is then defined if a segmented object is classified correctly even if not all of its voxels are detected. The object-based classification further improves precision and recall of the classifications (Tables 1 and 2). The average object-based precision for GHMRF classifications of tomograms without noise is 0.76 and 0.91 for sets 1 and 2, respectively. The corresponding average recall is 0.76 and 0.91. For set 2, the average precision at the highest noise level is 0.64 with a recall of 0.65, showing that >60% of all segmented objects were detected correctly.

3.3.3 Influence of the object placement.

To assess the influence of the object placement, 50 different tomograms were generated for sets 1 and 2. The classification results are robust with the SDs for the average precisions of about 0.1–0.2 for the initial and GHMRF-based classifications at all noise levels (Tables 1 and 2). SDs for the average object-based precisions are in a similar range.

3.3.4 Class member similarity.

There are generally two main reasons why some voxels are not correctly classified. First, voxels are unclassified and part of the background class (see class 4 in Fig. 6C). Second, identical complexes are sometimes grouped in two or more classes instead of a single class (Table 3, Fig. 6C). For instance, for the majority of tomograms in set 1, five instead of four recurrent classes have been identified (Table 3). In one example, the identical complexes of the class 3 were divided into two different groups after classification (see classes 3a and b in Fig. 6C). Although the complexes in the additional class are counted as false positives, all the members in the class are indeed identical complexes in this example. In general, for low noise levels ≈96% and for high noise levels ≈91% of the complexes in the same class are of the same type. It is, therefore, possible to align the subtomograms of these complexes in each class and generate an average density map of the complex with improved SNR. It may then be possible to identify sufficient similarities among the class-averaged density maps to redefine them to the same class.

Table 3.

The number of classes (excluding the background class) detected in 50 tomogram classifications of set 1 (Table 1)

| Classes | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNR | ∞ | 0 | 0 | 3 | 15 | 19 | 11 | 2 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 11 | 16 | 10 | 3 | 0 | |

| 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 18 | 12 | 9 | 3 | 1 | |

| 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 17 | 14 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

Each of the 50 tomograms contains 40 randomly placed and oriented protein complexes of four different classes.

4 CONCLUSIONS

We have introduced an inference-based template-free method for the detection and classification of frequently occurring protein complexes in tomograms. We have assessed our method on realistically simulated cryo electron tomograms at 4 nm resolution, which contain noise and distortions due to missing wedge and electron optical factors. Our method relies on an initial classification, which uses rotation-invariant feature vectors to provide an efficient way to calculate the similarity between segmented objects. This initial classification is further refined using an GHMRF model, which is less prone to noise and distortions and therefore improves the initial classification significantly. Indeed, for tomograms with an SNR of 0.5, between 44% and 51% of all voxels and between 64% and 71% of all segmented objects are classified correctly. Misclassification is mainly due to the grouping of identical complexes into separate classes. Importantly, more than 91% of complexes assigned to the same class are identical even at high noise levels. These results are encouraging and demonstrate that in principle it is possible to discover new complexes in cryo electron tomograms in an efficient manner.

The current work represents a first proof-of-principle of the method. Future improvements will focus on optimizing the method toward higher concentrations of complexes to levels observed in the crowded cell cytoplasm. Moreover, a number of limitations to visual proteomics might be overcome by further technical developments. In future, it may be possible to improve the moderate SNR level in cryoET, for instance, by improving the contrast in tomograms through phase plates (Murata et al., 2010). Furthermore, specimen thinning techniques through focused ion beams (Murata et al., 2010) will be crucial for improving SNR and imaging larger cell types, such as eukaryotic cells. Finally, direct electron detection systems promise to largely improve SNR of cameras (Murata et al., 2010), which will be highly beneficial for cryoET. In summary, our results demonstrate the detection of frequently occurring complexes in tomographic maps, even at low SNR levels and without the need of available template structures. Our method can facilitate the discovery of new complexes in cryo electron tomograms. This task provides a step toward unbiased visual proteomics of cells, which aims to discover the shapes, abundance and spatial distributions of all large protein complexes in a cell.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Shihua Zhang for his valuable suggestions and discussions.

Funding: Human Frontier Science Program (RGY0079/2009-C to F.A.); National Institute of Health (NIH) (1R01GM096089 and 2U54RR022220-06 to F.A.), Alfred P. Sloan Research foundation (to F.A.); F.A. is a Pew Scholar in Biomedical Sciences, supported by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Alber F., et al. Integrating diverse data for structure determination of macromolecular assemblies. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.060407.135530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M., et al. Visual proteomics of the human pathogen Leptospira interrogans. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:817–823. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M., et al. Exploring the spatial and temporal organization of a cell's proteome. J. Struct. Biol. 2011;173:483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besag J. On the statistical analysis of dirty pictures. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1986;48:259–302. [Google Scholar]

- Best C., et al. Localization of protein complexes by pattern recognition. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;79:615–638. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)79025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhm J., et al. Toward detecting and identifying macromolecules in a cellular context: template matching applied to electron tomograms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci USA. 2000;97:14245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230282097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty E. Mathematical Morphology in Image Processing. Boca Raton, FL. USA: CRC Press, Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Förster F., et al. Classification of cryo-electron sub-tomograms using constrained correlation. J. Struct. Biol. 2008;161:276–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangakis A., et al. Identification of macromolecular complexes in cryoelectron tomograms of phantom cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172520299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J. Three-dimensional Electron Microscopy of Macromolecular Assemblies: Visualization of Biological Molecules in Their Native State. USA: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Han B., et al. Survey of large protein complexes in D. vulgaris reveals great structural diversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:16580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813068106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington J., Salibián-Barrera M. Finding approximate solutions to combinatorial problems with very large data sets using BIRCH. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Hobson E. The Theory of Spherical and Ellipsoidal Harmonics. Cambridge, England: 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Kazhdan M., et al. Proceedings of the 2003 Eurographics/ACM SIGGRAPH symposium on Geometry processing. Switzerland, Switzerland: Eurographics Association Aire-la-Ville; 2003. Rotation invariant spherical harmonic representation of 3D shape descriptors; pp. 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley L., et al. An automated approach for clustering an ensemble of nmR-derived protein structures into conformationally related subfamilies. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 1996;9:1063. doi: 10.1093/protein/9.11.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., et al. Automatic cortical sulcal parcellation based on surface principal direction flow field tracking. NeuroImage. 2009;46:923–937. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. Markov Random Field Modeling in Image Analysis. New York, USA: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lučić V., et al. Structural studies by electron tomography: from cells to molecules. Biochemistry. 2005;74:833. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullan G., et al. Detective quantum efficiency of electron area detectors in electron microscopy. Ultramicroscopy. 2009;109:1126–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medalia O., et al. Macromolecular architecture in eukaryotic cells visualized by cryoelectron tomography. Science. 2002;298:1209. doi: 10.1126/science.1076184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K., et al. Zernike phase contrast cryo-electron microscopy and tomography for structure determination at nanometer and subnanometer resolutions. Structure. 2010;18:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy G., Jensen G. Electron cryotomography. BioTechniques. 2007;43:413–415. doi: 10.2144/000112568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickell S., et al. TOM software toolbox: acquisition and analysis for electron tomography. J. Struct. Biol. 2005;149:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha M., et al. MOTIF-EM: an automated computational tool for identifying conserved regions in CryoEM structures. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:i301. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangelder J., Veltkamp R. A survey of content based 3D shape retrieval methods. Multimedia Tools Appl. 2008;39:441–471. [Google Scholar]

- Wriggers W., et al. Situs: a package for docking crystal structures into low-resolution maps from electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 1999;125:185–195. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.4080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., et al. Bioinformatics and Biomedicine, 2009. BIBM'09. IEEE International Conference on. Los Alamitos, CA, USA: IEEE; 2009. 3D rotation invariant features for the characterization of molecular density maps; pp. 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., et al. BIRCH: a new data clustering algorithm and its applications. Data Min. Know. Discov. 1997;1:141–182. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., et al. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 2001;20:45–57. doi: 10.1109/42.906424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.