Abstract

Motivation: Pseudoknots found in secondary structures of a number of functional RNAs play various roles in biological processes. Recent methods for predicting RNA secondary structures cover certain classes of pseudoknotted structures, but only a few of them achieve satisfying predictions in terms of both speed and accuracy.

Results: We propose IPknot, a novel computational method for predicting RNA secondary structures with pseudoknots based on maximizing expected accuracy of a predicted structure. IPknot decomposes a pseudoknotted structure into a set of pseudoknot-free substructures and approximates a base-pairing probability distribution that considers pseudoknots, leading to the capability of modeling a wide class of pseudoknots and running quite fast. In addition, we propose a heuristic algorithm for refining base-paring probabilities to improve the prediction accuracy of IPknot. The problem of maximizing expected accuracy is solved by using integer programming with threshold cut. We also extend IPknot so that it can predict the consensus secondary structure with pseudoknots when a multiple sequence alignment is given. IPknot is validated through extensive experiments on various datasets, showing that IPknot achieves better prediction accuracy and faster running time as compared with several competitive prediction methods.

Availability: The program of IPknot is available at http://www.ncrna.org/software/ipknot/. IPknot is also available as a web server at http://rna.naist.jp/ipknot/.

Contact: satoken@k.u-tokyo.ac.jp; ykato@is.naist.jp

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

RNAs play various roles in biological processes, ranging from the passive role as a messenger that carries genetic information to the active roles as a regulator for gene expression and as a catalyst in cellular processes. Considerable attention has been paid to the functions of RNAs, especially those of regulatory non-coding RNAs (Eddy, 2001). It is widely believed that there is a strong correlation between the 3D structure of an RNA molecule and its function. A set of base pairs formed from hydrogen bonds is called a secondary structure, which shapes the substructure of the 3D structure. Since experimental determination of RNA 3D structures is difficult and their structures are hierarchical, secondary structure prediction provides a major key to elucidating the potential functions of RNAs.

A good number of computational studies have so far been presented on RNA secondary structure prediction. They can be roughly classified into two groups, namely comparative sequence analysis and single sequence analysis. Comparative methods based on alignment folding include RNAalifold (Bernhart et al., 2008; Hofacker et al., 2002) and Pfold (Knudsen and Hein, 2003). The comparative analysis has an advantage of a fair possibility of achieving high prediction accuracy since it can take evolutionary information into consideration. However, this approach is not always applicable since a set of homologous sequences is required in advance. As for single sequence analysis, a popular approach is to find the structure with the minimum free energy (MFE) of a single RNA sequence. We can use programs that implement this strategy based on dynamic programming (DP) algorithms such as mfold (Zuker, 2003; Zuker and Stiegler, 1981) and RNAfold (Hofacker et al., 1994; Hofacker, 2003). Notice that the free energy of a secondary structure is calculated by summing energy parameters of respective loop substructures, which can be experimentally determined and computationally estimated (Mathews et al., 1999). Furthermore, these DP-based methods are applied to the calculation of the partition function for RNA secondary structures (McCaskill, 1990), which enables us to compute posterior base-pairing probabilities. Recently, several sophisticated methods have been proposed for predicting the secondary structure with the maximum expected accuracy (MEA) over a space of possible structures. CONTRAfold (Do et al., 2006) and CentroidFold (Hamada et al., 2009a) that adopt this idea achieve better prediction accuracy as compared with the MFE-based methods. It is to be noted that all of the above methods aim to predict relatively simple RNA structures with nested base-pairing interactions.

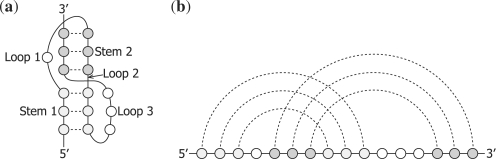

Pseudoknot is one of the important topologies in RNA secondary structures. A pseudoknot is typically formed from the base pairings between the unpaired bases of a loop and those outside the loop, which is often called an H-type pseudoknot (see Fig. 1a). In other words, a secondary structure includes a pseudoknot if at least two arcs drawn above the primary sequence that represent base pairs cross each other (see Fig. 1b). Pseudoknotted structures are observed in many RNAs such as ribosomal RNAs, transfer messenger RNAs and viral RNAs (van Batenburg et al., 2001). Pseudoknots are known to be involved in the regulation of translation and splicing, and ribosomal frame shifting (Brierley et al., 2007; Staple and Butcher, 2005). Furthermore, pseudoknots assist foldings in the 3D space in many cases (Fechter et al., 2001). It follows from these facts that pseudoknots should not be ignored for structural and functional analysis of RNAs.

Fig. 1.

A typical H-type pseudoknot. (a) A pseudoknot represented by three-loop nomenclature. Note that Loop 2 typically has zero or one base (Liu et al., 2010). (b) An arc representation of the pseudoknot.

Unlike the case of pseudoknot-free structure prediction stated above, predicting pseudoknotted structures is a difficult problem in a computational aspect. In particular, it is proven that the problem of finding the MFE structure including arbitrary pseudoknots is NP-hard (Akutsu, 2000; Lyngsø and Pedersen, 2000b). Therefore, several approaches have been proposed based on exact algorithms or heuristic methods in terms of finding an optimal structure (Akutsu, 2006; Liu et al., 2010). Examples of exact methods are DP algorithms that predict limited classes of pseudoknots in O(n4)~O(n6) time (Akutsu, 2000; Dirks and Pierce, 2003; Lyngsø and Pedersen, 2000a; Reeder and Giegerich, 2004; Rivas and Eddy, 1999), where n is the length of an input RNA sequence. Available programs among them are PKNOTS (Rivas and Eddy, 1999), NUPACK (Dirks and Pierce, 2003; 2004) and pknotsRG (Reeder and Giegerich, 2004). Besides, classification of the pseudoknot topologies handled by the DP-based algorithms was investigated (Condon et al., 2004). Another approach based on integer programming was proposed to predict the MFE secondary structure with recursive pseudoknots (Poolsap et al., 2009). All of the above methods, however, have a possibility of being intractable for long RNA sequences.

In contrast, several heuristic prediction methods have been proposed to circumvent the high-time complexity resulting from the nature of exact algorithms for finding the MFE pseudoknotted structure. ILM (Ruan et al., 2004), HotKnots (Ren et al., 2005) and FlexStem (Chen et al., 2008) predict secondary structures with pseudoknots, iteratively constructing pseudoknotted structures using algorithms for pseudoknot-free structure prediction. ProbKnot (Bellaousov and Mathews, 2010) assembles structures composed of the most probable base pairs from base-pairing probabilities that do not consider pseudoknots. From the viewpoint of employing comparative information, hxmatch (Witwer et al., 2004) as well as ILM predicts the consensus secondary structure with pseudoknots for aligned sequences. Although the optimality of a predicted structure computed by these algorithms is not guaranteed, they can deal with a wider class of pseudoknots than the DP-based exact methods can do, and have an advantage of being executable on long sequences.

Designing RNA energy models is also an important task to predict secondary structures of good quality. An energy model consists of structural features (fragments), energy parameters and a function that assigns a free energy change to a structure of a given sequence (Andronescu et al., 2010b). The Mathews–Turner model (Mathews et al., 1999) is widely used to predict RNA secondary structures without pseudoknots. The Dirks–Pierce model (Dirks and Pierce, 2003) includes the Mathews–Turner features and additional features for pseudoknots. The Cao–Chen model (Cao and Chen, 2006) includes the Dirks–Pierce features along with many new features for H-type pseudoknots. Recently, Andronescu et al. (2007, 2010b) have presented algorithms for refining energy parameters using a constraint generation approach and Boltzmann likelihood estimation. Moreover, (Andronescu et al., 2010a) have reported that HotKnots employing new energy parameters estimated by these training algorithms yields better prediction accuracy on pseudoknotted structural data as compared with the earlier version of HotKnots.

Although there are various approaches to predicting RNA pseudoknotted structures, only a few of them achieve satisfying predictions in both speed and accuracy. This is a crucial requirement especially when applying a prediction algorithm to finding functional non-coding RNAs in genome sequences. In this article, we present IPknot, a novel method for Integer Programming (IP)-based prediction of RNA pseudoKNOTs. IP, one of the optimization techniques, is useful for modeling a wide variety of combinatorial problems. Remember that one of the existing methods mentioned above uses IP to predict RNA pseudoknotted structures (Poolsap et al., 2009). Main differences between the earlier IP-based study and our newly proposed method lie in the objective functions and the classes of pseudoknots that they can handle. The important point to note is that IPknot significantly outperforms the earlier IP-based method in both prediction accuracy and running time. As in our previous method RactIP (Kato et al., 2010) for RNA–RNA interaction prediction, IPknot seeks to find the MEA secondary structure using IP. To compute the expected accuracy of a secondary structure with respect to an ensemble of all possible structures including pseudoknots, we decompose a pseudoknotted structure into a set of pseudoknot-free substructures and approximate a base-pairing probability distribution that considers pseudoknots. This decomposition enables IPknot to describe a wide class of pseudoknotted structures and perform quite fast predictions. In addition, we propose a heuristic algorithm for refining the base-pairing probabilities to improve the prediction accuracy of IPknot. The IP problem is solved partly by using the threshold cut technique, which fits in well with the idea of maximizing expected accuracy. We also extend IPknot so that it can predict the common secondary structure with pseudoknots when a multiple alignment of RNA sequences is given, employing the methodology of CentroidAlifold (Hamada et al., 2011) for pseudoknot-free consensus structure prediction. We validate the prediction performance of IPknot through extensive experiments on various datasets, making a comparison with several state-of-the-art prediction methods. The major advantages of this work in performance are summarized as follows:

Prediction performance of IPknot is sufficiently good in speed and accuracy as compared with ProbKnot (Bellaousov and Mathews, 2010), FlexStem (Chen et al., 2008), HotKnots (Ren et al., 2005; Andronescu et al., 2010a), pknotsRG (Reeder and Giegerich, 2004) and ILM (Ruan et al., 2004), which are methods for predicting pseudoknotted structures of a single RNA sequence in practical time.

IPknot yields robust predictions even when an alignment quality deteriorates. In fact, experimental results show that IPknot is more accurate than ILM and hxmatch (Witwer et al., 2004) on a dataset comprising sequence-based alignments rather than structural alignments.

In the remainder of this article, we present the algorithmic framework of the proposed method in Section 2. Section 3 provides experimental results using IPknot and other prediction methods. After discussing the results in Section 4, we conclude this article in Section 5.

2 METHODS

We present a new method IPknot for predicting pseudoknotted RNA secondary structures using integer programming (IP). IPknot executes the following two steps when an RNA sequence is given:

compute the base-pairing probabilities used in the IP objective function (Section 2.1);

solve the IP problem to predict the optimal pseudoknotted RNA secondary structure (Section 2.2).

In Section 2.3, we propose a heuristic algorithm for refining the base-pairing probabilities that compose the IP objective function in the first step. Furthermore, we extend our algorithm to common secondary structure prediction including pseudoknots in Section 2.4.

2.1 MEA-based scoring function for predicting pseudoknotted RNA secondary structures

Let Σ={A,C,G,U} and Σ* denote the set of all finite RNA sequences consisting of bases in Σ. For a sequence x=x1x2···xn∈Σ*, let |x| denote the number of symbols appearing in x, which is called the length of x. Let 𝒮(x) be a set of secondary structures of an RNA sequence x including pseudoknots. An element y∈𝒮(x) is represented as a |x|×|x| binary-valued triangular matrix y=(yij)i<j, where yij=1 means that bases xi and xj form a base pair.

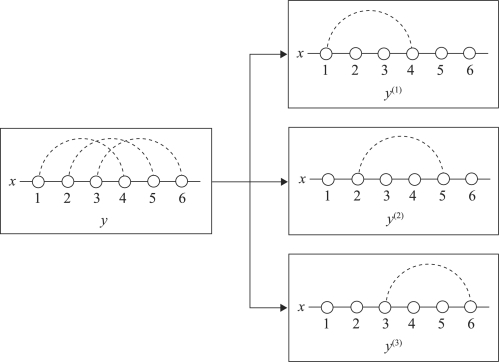

We assume that a secondary structure y∈𝒮(x) can be decomposed into a set of pseudoknot-free substructures (y(1),y(2),…,y(m)) that satisfies the following conditions: (i) y∈𝒮(x) should be decomposed into a mutually-exclusive set, that is, for all 1≤i<j≤|x|, ∑1≤p≤my(p)ij≤1; and (ii) every base pair in y(p) should be pseudoknotted to at least one base pair in y(q) for ∀q<p. Each pseudoknot-free substructure y(p) is said to belong to the level p (see Fig. 2). For any RNA secondary structure y∈𝒮(x), there exists a positive integer m such that y can be decomposed into m pseudoknot-free substructures [see Supplementary Section S6 and Jiang et al. (2010) for further details]. From this viewpoint, we can say that the above decomposition enables our method to model arbitrary pseudoknots.

Fig. 2.

An illustration of the decomposition of a pseudoknotted secondary structure y∈𝒮(x) into pseudoknot-free substructures (y(1),y(2),y(3)).

One of the most promising techniques to predict RNA secondary structures is the MEA-based approach including centroid estimation (Carvalho and Lawrence, 2008; Hamada et al., 2009a).

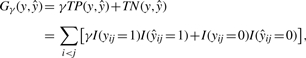

First, we define a gain function of ŷ∈𝒮(x) with regard to the correct secondary structure y∈𝒮(x) as follows:

|

(1) |

where γ>0 is a weight parameter for base pairs, TP and TN denote the numbers of true positives (base pairs) and true negatives (non-base pairs), respectively, and I(condition) is the indicator function that takes a value of 1 or 0 depending on whether the condition is true or false.

Our objective is to find a secondary structure ŷ that maximizes the expectation of the gain function (1) under a given probability distribution over the space 𝒮(x) of pseudoknotted secondary structures:

| (2) |

where P(y∣x) is a probability distribution of RNA secondary structures including pseudoknots. It has been proven that the γ-centroid estimator (2) enables us to decode accurate secondary structures from a given probability distribution (Hamada et al., 2009a).

Unfortunately, the calculation of Equation (2) is intractable for arbitrary pseudoknots (Akutsu, 2000; Lyngsø and Pedersen, 2000b). Instead, we can employ several models for limited classes of pseudoknots such as the Rivas–Eddy model (Rivas and Eddy, 1999), the Akutsu model (Akutsu, 2000), the Dirks–Pierce model (Dirks and Pierce, 2003; 2004) and the Reeder–Giegerich model (Reeder and Giegerich, 2004). However, even for relatively simple pseudoknotted structures, computationally expensive costs of O(|x|4)~O(|x|6) time and O(|x|2)~O(|x|4) space are required.

Therefore, we approximate the expected gain function (2) by the sum of the expected gain functions for each level of pseudoknot-free substructures (ŷ(1),…,ŷ(m)) in the decomposed set of a pseudoknotted structure ŷ∈𝒮(x), and thus simultaneously find a pseudoknotted structure ŷ and its decomposition (ŷ(1),…,ŷ(m)) that maximize:

|

(3) |

where α(p)>0 (∑pα(p)=1) is a weight parameter for each gain function at the level p (in our experiments, we fixed α(p)=1/m), γ(p)>0 is a weight parameter for base pairs at the level p, and C is a constant independent of ŷ [see the Supplementary Material of Hamada et al. (2009a) for the derivation]. The base-pairing probability pij is a probability that the base xi is paired with xj, which is defined as:

We can select P′(y∣x), a probability distribution over a set 𝒮′(x) of secondary structures with or without pseudoknots, from several approaches. A naïve approach is use of the probability distribution with pseudoknots as well as Equation (2) in spite of high computational costs. Alternatively, we can employ a probability distribution without pseudoknots such as the McCaskill model (McCaskill, 1990), whose computational complexity is O(|x|3) for time and O(|x|2) for space. Furthermore, a novel approach that refines the base-pairing probability matrix from the distribution without pseudoknots will be proposed in Section 2.3. Note that we implemented all the three approaches.

It is worth mentioning that IPknot can be regarded as an extension of CentroidFold (Hamada et al., 2009a). If we let the number of decomposed levels m=1, the approximate expected gain function (3) is identical to the γ-centroid estimator used in CentroidFold.

We should notice that the maximization of the approximate gain (3) is equivalent to the maximization of the weighted sum of the base-pairing probabilities pij larger than θ(p)=1/(γ(p)+1). Consequently, it is no longer necessary to consider the base pairs whose pairing probabilities are at most the thresholds θ(p), which we call threshold cut.

2.2 IP model

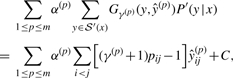

Maximization of the approximate expected gain (3) can be solved by the IP problem as follows:

| (4) |

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

| (7) |

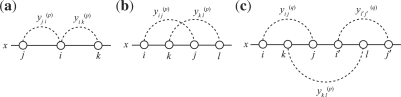

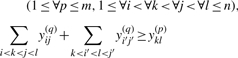

Since Equation (4) is an instantiation of the approximate estimator (3) and the threshold cut technique is applicable to Equation (3), we need to consider only base pairs y(p)ij whose base-pairing probabilities pij are larger than θ(p)=1/(γ(p)+1). The constraint (5) means that each base xi can be paired with at most one base. (Fig. 3a). The constraint (6) disallows pseudoknots within the same level p (Fig. 3b). The constraint (7) ensures that each base pair at the level p is pseudoknotted to at least one base pair at every lower level q<p (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

An illustration of the constraints of the IP formulation. The diagrams (a) and (b) correspond to the constraints (5) and (6), respectively. Note that at most one variable shown by a broken curved line can take a value 1. The diagram (c) corresponds to the constraint (7).

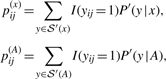

It is widely accepted that base pairs in stable RNA structures are likely to appear in a stacked form rather than an isolated one. Following the IP formulation proposed by Poolsap et al. (2009), we can avoid isolated base pairs by incorporating the stacked pairing constraints as follows:

| (8) |

| (9) |

where

These constraints guarantee that if a base xi is paired with another one, the base(s) adjacent to xi must also form a base pair.

2.3 An iterative refinement algorithm for the base-pairing probability matrix

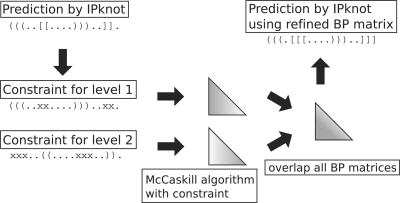

We propose an iterative algorithm that refines the base-pairing probabilities used in the objective function of our method. The basic idea is that the base-pairing probabilities are improved by the secondary structures predicted at the first stage, and then a new prediction is performed by the improved base-pairing probabilities (see also Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A schematic diagram of the iterative refinement algorithm for the base-pairing probability matrix. A constraint on secondary structure for each level is denoted by a variant of the dot-parenthesis format: a matching parenthesis ‘()’ denotes an allowed base pair, a character ‘x’ indicates an unpaired base, and a dot ‘.’ is used for an unconstrained base.

More specifically, for a given sequence x∈Σ*, we first predict a secondary structure ŷ=(ŷ(1),…,ŷ(m)) by solving the IP problem described as Equations (4)–(9). Then, for each level p, a constraint c(p) on secondary structure is constructed as follows: (i) for i,j such that ŷ(p)ij=1, only the base pair between xi and xj is allowed, but other base pairs that involve xi or xj are disallowed; and (ii) for i,j such that ŷ(q)ij=1 (q≠p), xi and xj cannot form base pairs at the level p. The base-pairing probabilities with the constraint c(p) can be defined as p(p)ij=∑y∈𝒮′c(p)(x)I(yij=1)P′(y∣x), where 𝒮′c(p)(x)⊂𝒮′(x) is a set of secondary structures that satisfies the constraint c(p). This calculation is performed by a variant of the McCaskill algorithm in O(|x|3) time and O(|x|2) space. Finally, using the updated base-pairing probabilities pij=∑pp(p)ij, we re-predict a secondary structure ŷ by solving the IP problem. These steps are iterated until an eligible condition (e.g. the number of iterations, the convergence of the prediction) is satisfied.

The probability distribution produced by the iterative refinement algorithm can be regarded as a mixture of the probability distribution for each level p of the preceding prediction of pseudoknot-free structures, which can represent a wider space of the distribution than the individual distribution of pseudoknot-free structures. This enables the iterative refinement algorithm to improve the base-pairing probability matrix.

2.4 Common secondary structure prediction including pseudoknots

It is well known that use of multiple alignments of homologous sequences improves the accuracy of predicting RNA secondary structures due to the alignment information such as covariation (Bernhart et al., 2008; Hamada et al., 2011). In order to implement the prediction of common secondary structures including pseudoknots for aligned sequences, we can apply the same methodology as CentroidAlifold (Hamada et al., 2011), which employs the mixture of the RNAalifold model (Bernhart et al., 2008) and the McCaskill model (McCaskill, 1990).

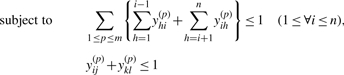

Let A be an alignment of RNA sequences that contains k sequences and |A| denote the number of columns of A. We can calculate the base-pairing probabilities of an individual sequence x∈A and those of the alignment A under the McCaskill model P′(y∣x) and the RNAalifold model P′(y∣A):

|

each of which can be computed by the dynamic programming technique in O(|A|3) time and O(|A|2) space. The base-pairing probabilities under the mixed distribution can be defined as:

| (10) |

where w∈[0, 1] is a weight parameter (in our experiments, we fixed w=1/2). The first term of Equation (10) contributes to the robustness against the alignment errors, and the second term improves the probability distribution by the covariance information on each column of the alignment.

We can predict the optimal common secondary structure including pseudoknots for aligned RNA sequences by solving the IP problem introduced in Section 2.2 with p*ij instead of pij. Note that the iterative refinement algorithm described in Section 2.3 can work as well as the case of individual sequences.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Implementation

Our method was implemented as a program called IPknot. We utilized the McCaskill model (McCaskill, 1990) and the RNAalifold model (Bernhart et al., 2008) in the Vienna RNA package (Hofacker, 2003) to calculate base-pairing probabilities, employing the free energy parameters estimated by the Boltzmann likelihood method (Andronescu et al., 2010b). We also implemented the Dirks–Pierce (D&P) model (Dirks and Pierce, 2003; 2004) that calculates the base-pairing probabilities including a limited class of pseudoknots in O(n5) time and O(n4) space, where n is the length of a given sequence. To solve the IP problem, IPknot can use the GNU Linear Programming Kit (GLPK; http://www.gnu.org/software/glpk/), Gurobi optimizer (http://gurobi.com/) or IBM ILOG CPLEX optimizer (http://www-01.ibm.com/software/integration/optimization/cplex-optimizer/). The source code of IPknot is freely available at http://www.ncrna.org/software/ipknot/. IPknot is also available as a web server at http://rna.naist.jp/ipknot/.

3.2 Data

We validated IPknot using three datasets of RNA sequences with pseudoknotted secondary structures.

The first dataset was obtained from the RNA STRAND database (Andronescu et al., 2008), which contains only carefully curated sequences and structures. We selected the RNA sequences with at least one pseudoknot whose length is between 140 nt and 500 nt. To reduce redundant sequences, we filtered out the sequences that have more than 85 % identity to the other sequences. As a result, 388 non-redundant sequences were obtained. We call this ‘RS-pk388’ dataset.

The second dataset is called ‘pk168’ dataset, originally established by (Huang and Ali, 2007). The pk168 dataset is compiled from PseudoBase (van Batenburg et al., 2001), which includes 16 categories of pseudoknots. After excluding the redundant sequences (>85% identity), the test set includes 168 sequences whose lengths are <140 nt. This dataset was also used by recent studies (Chen et al., 2008; Huang and Ali, 2007).

For the benchmark of prediction of common secondary structures including pseudoknots for aligned RNA sequences, we created the third dataset from Rfam 10.0 (Gardner et al., 2011). Only manually curated seed alignments with consensus structures published in literature were used. We produced 67 alignments containing five sequences from the Rfam families that satisfy the following conditions: (i) at least one pseudoknot is included; (ii) the length is at most 500 nt; and (iii) at least five sequences are contained. We call this ‘Rfam-PK’ dataset. In order to evaluate the robustness against the alignment errors, we realigned every alignment by ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994), which considers no structural information such as covariation.

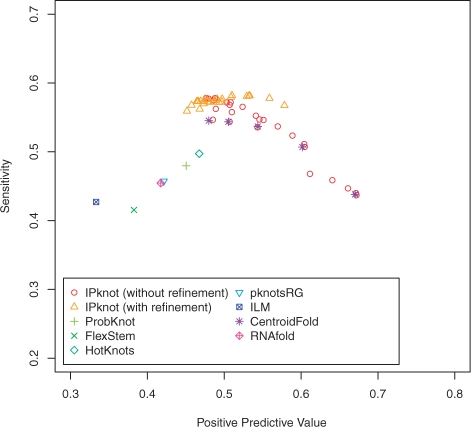

3.3 Prediction of secondary structures including pseudoknots

The experiment on the RS-pk388 dataset was conducted, comparing our algorithm with several state-of-the-art methods that can predict pseudoknots including ProbKnot (Bellaousov and Mathews, 2010), FlexStem (Chen et al., 2008), HotKnots (Andronescu et al., 2010a; Ren et al., 2005), pknotsRG (Reeder and Giegerich, 2004) and ILM (Ruan et al., 2004), and those that can predict only pseudoknot-free structures including CentroidFold (Hamada et al., 2009a) and RNAfold (Hofacker, 2003).

For IPknot, we fixed the number of decomposed sets of secondary substructures m=2, and varied the weight parameters for the expected number of true positive base pairs in such a way that γ(p)∈{2k∣k=0,1,2,3,4}. Since CentroidFold has the weight parameters for the expected number of true positive base pairs as well as IPknot, the same range of parameters was applied to these two methods. For HotKnots, DP09 parameters estimated by (Andronescu et al., 2010a) were employed. For the other competitive methods, the default settings were used.

We evaluated prediction accuracy through positive predictive value (PPV) and sensitivity (Sen) with respect to base pairs defined as follows:

where TP is the number of correctly predicted base pairs, FP is the number of incorrectly predicted base pairs, and FN is the number of base pairs in the true structure that were not predicted.

Figure 5 shows the PPV–Sensitivity plots for respective algorithms. Note that the sets of points with the same shape plotted for IPknot and CentroidFold correspond to the results obtained by changing values of the weight parameters γ(p). The results clearly indicate that IPknot is more accurate than the existing methods on the RS-pk388 dataset. It can also be seen that the iterative refinement algorithm improves the prediction accuracy of IPknot.

Fig. 5.

The PPV–Sensitivity plots of the experiment on the RS-pk388 dataset.

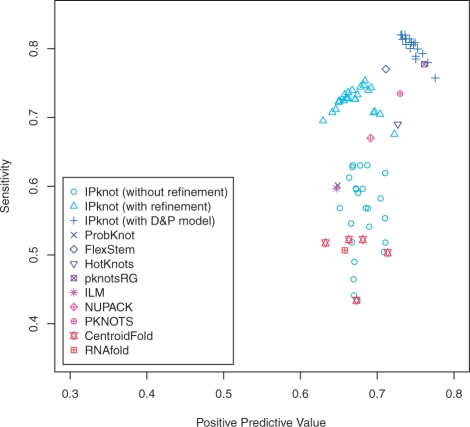

Since the pk168 dataset contains shorter sequences than the RS-pk388 dataset, more accurate but computationally expensive prediction algorithms can be applied to this dataset. For the pk168 dataset, we evaluated IPknot with the D&P model (Dirks and Pierce, 2003; 2004) that calculates the exact base-pairing probabilities including a limited class of pseudoknots. Furthermore, our method was compared with the DP-based algorithms including NUPACK (Dirks and Pierce, 2003; 2004) and PKNOTS (Rivas and Eddy, 1999), as well as the competitive methods used in the previous experiment. Figure 6 shows the accuracy on the pk168 dataset, indicating that IPknot with the D&P model is comparable to pknotsRG, which achieves the best accuracy.

Fig. 6.

The PPV–Sensitivity plots of the experiment on the pk168 dataset.

We evaluated the time efficiency of IPknot using GLPK as the IP solver and the competitive methods on Linux OS with Intel Quad Core Xeon E5450 (3.0 GHz) and 32 GB memory. Five sequences PKB229, PKB134 (from the pk168 dataset), ASE_00193, CRW_00614 (from the RS-pk388 dataset) and CRW_00774 (from the RNA STRAND database) were used to measure the elapsed time to predict secondary structures. Table 1 indicates that IPknot is significantly faster than the existing algorithms for predicting pseudoknotted secondary structures. It should be noted that the reason why IPknot with the D&P model takes long running time is not due to solving the IP problem but due to computing the exact base-pairing probabilities that consider pseudoknots.

Table 1.

Comparison of time performance between different algorithms

| ID | PKB229 | PKB134 | ASE_00193 | CRW_00614 | CRW_00774 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| length (nt) | 67 | 137 | 301 | 494 | 989 |

| IPknot | |||||

| (without refinement) | 0.01 s | 0.04 s | 0.19 s | 0.63 s | 6.40 s |

| (with refinement) | 0.01 s | 0.05 s | 0.28 s | 0.94 s | 18.0 s |

| (with D&P model) | 8.63 s | 8 m 26 s | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| ProbKnot | 0.06 s | 0.32 s | 4.52 s | 23.5 s | 1 m 58 s |

| FlexStem | 0.49 s | 0.68 s | 5.24 s | 1 m 5 s | 15 m 28 s |

| HotKnots | 4.24 s | 44.0 s | 32 m 12 s | 125 m 5 s | 133 m 10 s |

| pknotsRG | 0.02 s | 0.28 s | 3.29 s | 24.1 s | 6 m 50 s |

| ILM | 0.02 s | 0.12 s | 0.21 s | 1.32 s | 23.9 s |

| NUPACK | 1.91 s | 24.1 s | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CentroidFold | 0.01 s | 0.04 s | 0.19 s | 0.59 s | 6.36 s |

| RNAfold | <0.01 s | 0.01 s | 0.07 s | 0.21 s | 0.85 s |

N/A means that we were unable to complete calculation on our machine.

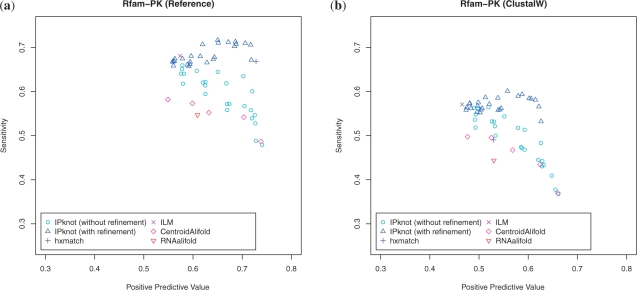

3.4 Prediction of common secondary structures including pseudoknots

A few number of algorithms for common secondary structure prediction with pseudoknots have been available. In this experiment, we compared IPknot with hxmatch (Witwer et al., 2004) and ILM (Ruan et al., 2004) for pseudoknotted common secondary structure prediction in addition to CentroidAlifold (Hamada et al., 2011) and RNAalifold (Bernhart et al., 2008) for pseudoknot-free common secondary structure prediction. We evaluated the accuracy through PPV and sensitivity for common secondary structures by mapping them to the individual sequences in the multiple alignments. The experimental results are shown in Figure 7. For the hand-curated reference alignments, hxmatch and IPknot with the iterative refinement algorithm achieve almost the same level of accuracy (see Fig. 7a). However, the alignments of low quality produced by ClustalW cause significantly worse accuracy of hxmatch compared with IPknot (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, in the Supplementary paper, the results of the experiments on multiple alignments produced by ProbCons (Do et al. , 2005) optimized for non-coding RNAs (called ProbConsRNA) and CentroidAlign (Hamada et al., 2009b) for RNA structural alignments are shown in Supplementary Figure S3. These results suggest that IPknot has the robustness against the alignment errors compared with the existing methods such as hxmatch and ILM.

Fig. 7.

The PPV–Sensitivity plots of the experiment on the Rfam-PK dataset. (a) The results for reference alignments. (b) The results for sequence-based alignments produced by Clustal W.

4 DISCUSSION

IPknot predicts a pseudoknotted secondary structure that maximizes the approximate expected gain function (3), which represents the expectation of the (weighted) number of true predictions of base pairs under a given probability distribution. We can regard this approach as maximizing expected accuracy, which has been successfully applied into various problems (Carvalho and Lawrence, 2008; Do et al. , 2005; Do et al., 2006; 2008; Hamada et al., 2009a; b; 2010; 2011; Kato et al., 2010; Knudsen and Hein, 2003). Recent studies have revealed that MEA-based methods can achieve more accurate predictions than other methods such as the maximum a posterior (MAP)-based and MFE-based methods, even from the same probability distribution. In fact, as shown in Figure 6, IPknot with the D&P model is much superior to NUPACK, both of which employ the same probability distribution (the D&P model) but different in decoding algorithms (based on MEA and MFE, respectively).

The threshold cut technique that enables IPknot to run fast is derived from Equation (3), which suggests that too large γ(p) is not suitable for the balanced accuracy measures such as Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) and F-measure. It should be emphasized that base pairs whose probability is less than the threshold will make the accuracy degenerate in expectation. Using the threshold cut technique, IPknot as well as RactIP (Kato et al., 2010) makes the IP problem so sparse that practical problems such as RNA pseudoknotted secondary structure prediction and RNA–RNA joint secondary structure prediction can be solved even by the IP solver that is freely available but inferior in performance.

Comparative experiments with the existing methods on single RNA sequences show that IPknot produces better predictions in accuracy on long RNA sequences, whereas its relative accuracy drops on short sequences, especially for IPknot without refinement. One possible explanation for these results is that for short sequences, many base pairs with high probabilities are likely to be predicted at the level 1, resulting in scarcity of base pairs predicted at the level 2. Nevertheless, the iterative refinement algorithm enhances the base-pairing probabilities at the level 2 by masking the base pairs predicted at the level 1, leading to improve prediction accuracy on short sequences.

As shown in Section 3.4, IPknot can perform robust predictions of consensus structures when a multiple alignment of RNA sequences is given. This is mainly due to use of Equation (10) that represents the mixture distribution of sequence-based and alignment-based probabilities. Unlike the competitive methods based only on covariance information, the averaged base-pairing probabilities described in the first term of Equation (10) play an important role in keeping the quality of prediction when the alignment quality gets worse.

IPknot has several parameters that users should select, including the weights for true positive base pairs at the level p (γ(p) in Equation (3)), the number of decomposed levels of pseudoknots, and the number of iterations of the iterative refinement algorithm. As well as CentroidFold and CentroidAlifold, the weights γ(p) for true positive base pairs control the balance of PPV and sensitivity. Since a set of larger γ(p) predicts more base pairs, sensitivity will increase. However, false positive base pairs will also increase and thus will make PPV decrease. Furthermore, the threshold values of the base-pairing probabilities to consider in the object function (4) depend on γ(p). This means that if we select too large γ(p), the performance of IPknot will degenerate since the IP problem to solve enlarges. Therefore, it is a crucial issue to determine appropriate parameters γ(p), although we showed the results on several sets of γ(p) in this article. To this end, we can take two approaches. First, use of the best pseudo-expected MCC (Hamada et al., 2010) among several sets of γ(p) can be mentioned. The pseudo-expected MCC is a good approximation of expected MCC, which can be calculated from the base-pairing probabilities. As the second approach, we can use machine learning techniques such as the max-margin method (Do et al., 2008), which will adopt the parameters to given training datasets.

As shown in Section 3, the improved base-pairing probability matrices by the iterative refinement algorithm made the prediction accuracy much elevated, especially for short sequences. In these experiments, relatively small γ(p) such as a pair of γ(1)=1 and γ(2)=1 achieved favorable performance, suggesting that use of only probable base pairs predicted by large thresholds at the first step would produce reliable base-pairing probabilities for the second step. Another important factor in the performance of IPknot is the number of iterations of the iterative refinement algorithm. Significant improvement was observed when applying the refinement algorithm once as compared with no refinement. On the other hand, we could not find meaningful difference between running the algorithm once and twice as shown in Supplementary Figure S4. Since each iteration is a time-consuming procedure, it seems reasonable to suppose that performing the iteration algorithm once is sufficient.

The maximum complexity of a secondary structure predicted by IPknot is restricted by the number m of decomposed levels of pseudoknots, which is also called an m-partite RNA secondary structure (Jiang et al., 2010), defined as the union of m pseudoknot-free substructures. A recent study has implied that most known RNA secondary structures are either bipartite or tripartite, i.e. m-partite for m=2 or 3 (Rødland, 2006). Supplementary Figure S5 in the supplementary paper shows the experiments on the RS-pkfree141 (pseudoknot-free) dataset and the RS-pk388 (pseudoknotted) dataset for the maximum decomposed level m=1,2,3. Note again that CentroidFold is equivalent to IPknot with the maximum decomposed level m=1. It can be observed that the selection of a conflicting level between predicted structures and correct structures causes the degradation of the accuracy compared with the best results. For example, for the pseudoknot-free dataset, IPknot with the maximum decomposed level m=3 and the iterative refinement algorithm cut down the accuracy compared with CentroidFold because of increasing false positive base pairs. These results indicate that the appropriate number of decomposed levels should be selected, although correct structures might be unknown. Rødland (2006) has revealed that among the hundreds of known RNA secondary structures with pseudoknots in PseudoBase (van Batenburg et al., 2001), only one structure is tripartite and others are all bipartite. This fact suggests that IPknot will work satisfactorily on average if we select the number of decomposed levels m=2.

5 CONCLUSION

We proposed a new computational method IPknot for predicting RNA secondary structures with a wide class of pseudoknots, which can take either a single sequence or aligned sequences as input. We demonstrated using a variety of structural datasets that IPknot is sufficiently fast and accurate as a computational prediction tool for both single sequence analysis and comparative sequence analysis.

Prediction accuracy of IPknot depends mainly on its scoring functions even though the method uses the approximate probability distribution for pseudoknotted structures. In fact, experimental results revealed that IPknot with the base-pairing probabilities computed by heuristic refinement produces much better predictions than that without refinement. Moreover, when we adopted the exact probabilities for pseudoknots, a significant improvement in accuracy was confirmed, though much computation time was spent on the predictions. Considering these results, there is room for further investigation into refinement of the scoring functions that make prediction accuracy compatible with running time.

Another important fact to stress is that IPknot can run quite fast even on a relatively long sequence less than one thousand bases. This is attributed to use of both approximation of a probability distribution for pseudoknots and integer programming with threshold cut based on maximizing expected accuracy. As described in Section 1, prediction methods with satisfying speed and accuracy are useful for finding functional non-coding RNA genes from genome sequences. Making skillful use of the speed and accuracy of our method, exhaustive search for genes of non-coding RNAs that may form pseudoknots is a worthwhile task as another future work.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We wish to thank our colleagues from the RNA Informatics Team at the Computational Biology Research Center (CBRC) for fruitful discussions. The super-computing resource was provided by Human Genome Center, Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo.

Funding: Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (KAKENHI) from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan [#22700305 (to K.S.); #22700313 (to Y.K.)]; Global COE program ‘Deciphering Biosphere from Genome Big Bang’ from MEXT, Japan (to K.S. and K.A., in part); Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas from MEXT, Japan (to M.H. and K.A., in part). Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Akutsu T. Dynamic programming algorithms for RNA secondary structure prediction with pseudoknots. Discrete Appl. Math. 2000;104:45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Akutsu T. Recent advances in RNA secondary structure prediction with pseudoknots. Current Bioinform. 2006;1:115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Andronescu M., et al. Efficient parameter estimation for RNA secondary structure prediction. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:i19–i28. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andronescu M., et al. RNA STRAND: the RNA secondary structure and statistical analysis database. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:340. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andronescu M., et al. Improved free energy parameters for RNA pseudoknotted secondary structure prediction. RNA. 2010a;16:26–42. doi: 10.1261/rna.1689910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andronescu M., et al. Computational approaches for RNA energy parameter estimation. RNA. 2010b;16:2304–2318. doi: 10.1261/rna.1950510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellaousov S., Mathews D.H. ProbKnot: fast prediction of RNA secondary structure including pseudoknots. RNA. 2010;16:1870–1880. doi: 10.1261/rna.2125310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhart S.H., et al. RNAalifold: improved consensus structure prediction for RNA alignments. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:474. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierley I., et al. Viral RNA pseudoknots: versatile motifs in gene expression and replication. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:598–610. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S., Chen S.J. Predicting RNA pseudoknot folding thermodynamics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2634–2652. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho L.E., Lawrence C.E. Centroid estimation in discrete high-dimensional spaces with applications in biology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3209–3214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712329105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., et al. FlexStem: improving predictions of RNA secondary structures with pseudoknots by reducing the search space. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1994–2001. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon A., et al. Classifying RNA pseudoknotted structures. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2004;320:35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dirks R.M., Pierce N.A. A partition function algorithm for nucleic acid secondary structure including pseudoknots. J. Comput. Chem. 2003;24:1664–1677. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirks R.M., Pierce N.A. An algorithm for computing nucleic acid base-pairing probabilities including pseudoknots. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1295–1304. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do C.B., et al. ProbCons: probabilistic consistency-based multiple sequence alignment. Genome Res. 2005;15:330–340. doi: 10.1101/gr.2821705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do C.B., et al. CONTRAfold: RNA secondary structure prediction without physics-based models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:e90–e98. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do C.B., et al. A max-margin model for efficient simultaneous alignment and folding of RNA sequences. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:i68–i76. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy S.R. Non-coding RNA genes and the modern RNA world. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001;2:919–929. doi: 10.1038/35103511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fechter P., et al. Novel features in the tRNA-like world of plant viral RNAs. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2001;58:1547–1561. doi: 10.1007/PL00000795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner P.P., et al. Rfam: Wikipedia, clans and the “decimal” release. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D141–D145. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada M., et al. Prediction of RNA secondary structure using generalized centroid estimators. Bioinformatics. 2009a;25:465–473. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada M., et al. CentoroidAlign: fast and accurate aligner for structured RNAs by maximizing expected sum-of-pairs score. Bioinformatics. 2009b;25:3236–3243. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada M., et al. Prediction of RNA secondary structure by maximizing pseudo-expected accuracy. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11:586. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada M., et al. Improving the accuracy of predicting secondary structure for aligned RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:393–402. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofacker I.L. Vienna RNA secondary structure server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3429–3431. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofacker I.L., et al. Secondary structure prediction for aligned RNA sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;319:1059–1066. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00308-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofacker I.L., et al. Fast folding and comparison of RNA secondary structures. Monatsh. Chem. 1994;125:167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Ali H. High sensitivity RNA pseudoknot prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:656–663. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M., et al. K-partite RNA secondary structures. J. Comput. Biol. 2010;17:915–925. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2009.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y., et al. RactIP: fast and accurate prediction of RNA–RNA interaction using integer programming. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:i460–i466. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen B., Hein J. Pfold: RNA secondary structure prediction using stochastic context-free grammars. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3423–3428. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., et al. RNA pseudoknots: folding and finding. F1000 Biol. Rep. 2010;2:8. doi: 10.3410/B2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyngsø R.B., Pedersen C.N.S. Pseudoknots in RNA secondary structures. Proc. 4th Ann. Intl. Conf. Comput. Mol. Biol. (RECOMB2000) 2000a:201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Lyngsø R.B., Pedersen C.N.S. RNA pseudoknot prediction in energy-based models. J. Comput. Biol. 2000b;7:409–427. doi: 10.1089/106652700750050862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews D.H., et al. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;288:911–940. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaskill J.S. The equilibrium partition function and base pair binding probabilities for RNA secondary structure. Biopolymers. 1990;29:1105–1119. doi: 10.1002/bip.360290621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poolsap U., et al. Prediction of RNA secondary structure with pseudoknots using integer programming. BMC Bioinform. 2009;10(Suppl 1):S38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-S1-S38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder J., Giegerich R. Design, implementation and evaluation of a practical pseudoknot folding algorithm based on thermodynamics. BMC Bioinform. 2004;5:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J., et al. HotKnots: heuristic prediction of RNA secondary structures including pseudoknots. RNA. 2005;11:1494–1504. doi: 10.1261/rna.7284905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas E., Eddy S.R. A dynamic programming algorithm for RNA structure prediction including pseudoknots. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:2053–2068. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rødland E.A. Pseudoknots in RNA secondary structures: representation, enumeration, and prevalence. J. Comput. Biol. 2006;13:1197–1213. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2006.13.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan J., et al. An iterated loop matching approach to the prediction of RNA secondary structures with pseudoknots. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:58–66. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staple D.W., Butcher S.E. Pseudoknots: RNA structures with diverse functions. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D., et al. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Batenburg F.H.D., et al. PseudoBase: structural information on RNA pseudoknots. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:194–195. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witwer C., et al. Prediction of consensus RNA secondary structures including pseudoknots. IEEE Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2004;1:66–77. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2004.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M., Stiegler P. Optimal computer folding of large RNA sequences using thermodynamics and auxiliary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:133–148. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.