Abstract

Secondary metabolites from microorganisms have a broad spectrum of applications, particularly in therapeutics. The growing number of sequenced microbial genomes has revealed a remarkably large number of natural product biosynthetic clusters for which the products are still unknown. These cryptic clusters are potentially a treasure house of medically useful compounds. The recent development of new methodologies has made it possible to begin unlock this treasure house, to discover new natural products and determine their biosynthesis pathways. This review will highlight some of the most recent strategies to activate silent biosynthetic gene clusters and to elucidate of their corresponding products and pathways.

Introduction

Natural products and their semisynthetic derivatives have been an important source of drugs in the pharmaceutical industry. Efforts to discover new bioactive treasures have recently benefited from the sequencing of ever-increasing numbers of genomes from natural-product-producing microbes. It is clear from the genome information that most of these microorganisms have the potential to produce a far greater number of natural products than have been isolated previously ([1] and the references cited therein). It seems that when these microorganisms are cultured under standard laboratory conditions, most biosynthetic gene clusters are either silent or expressed at very low levels. The chemical or environmental signals necessary for triggering these pathways must be missing.

In this review we will use the term “orphan” and “silent” gene clusters as suggested by Gross [2]. Orphan biosynthetic gene clusters are clusters for which the corresponding metabolite is still undiscovered. Silent clusters are clusters in which the genes are not expressed or expressed at very low levels. This review article will highlight some of the most recent developments and strategies to activate silent gene clusters that contains polyketide synthases (PKSs) and nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) and identify the products of orphan pathways. For more comprehensive reviews on PKSs and NRPSs, the reader is directed to works authored by Fischbach and Walsh [3,4], and Hertweck [5].

Recent advances in awakening silent gene clusters

Several strategies for the discovery of novel natural products by awakening silent gene clusters have been developed [1,6–9]. These strategies include the one strain-many compounds (OSMAC) approach, where new compounds can be elicited by cultivating microorganisms in different fermentation conditions. Parameters that have been manipulated include media composition, aeration rate, type of culture vessel, and the addition of enzyme inhibitors [10]. While very useful, this approach can be laborious and there is no certainty that conditions can be found to stimulate the synthesis of all the interesting and useful compounds that organisms can potentially produce.

An alternative strategy takes advantage of the fact that many secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters contain one or more genes that encode transcription factors that transcribe all the genes of the cluster. In organisms amenable to molecular genetic manipulation, the promoter of the transcription factor can be replaced by an inducible promoter. The synthesis of the transcription factor is, thus, removed from natural controls and put under the control of the researcher. Induction leads to high levels of the transcription factor and this, in turn, can lead to all of the genes of the cluster being turned on and the product produced [11,12]. This approach has the advantage that the product is immediately ascribable to the target cluster and it offers the potential for production of large amounts of the product. Some transcription factors are regulated post-translationally [13], however and it is possible that this strategy will not work easily for many of the clusters that contain transcription factor genes. In addition, many clusters do not contain transcription factor genes and other approaches must be used.

In addition to cluster-specific transcription factors, there are more general regulators of secondary metabolite gene expression. One example is LaeA, a nuclear protein that controls secondary metabolite gene expression. Using microarray analysis of strains over expressing laeA and strains carrying a deletion of laeA, the biosynthetic gene cluster of terrequinone A in A. nidulans was discovered [14].

Epigenetic regulation/Chromatin-level remodeling in eukaryotes

Histone modifications that alter the chromatin landscape such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ADP-ribosylation, glycosylation, ubiquitination and sumoylation have also been shown to regulate gene transcription (figure 1a). The Keller group demonstrated the importance of histone acetylation on the regulation of natural products in Aspergillus [15]. Disruption of the hdaA gene encoding an A. nidulans histone deacetylase (HDAC) led to the increased production of sterigmatocystin and penicillin.

Figure 1.

Recent advances in awakening silent gene clusters. (a) Chromatin-level remodeling, a proposed model by which relaxed chromatin leads to the de-repression of secondary metabolite biosynthesis. The COMPASS complex represses the production of emodin and related compounds, monodictyphenone, and F-9775A/F-9775B. (b) Fungal-bacterial physical interaction induced the silent gene cluster (ors) and the production of secondary metabolites. (c) Ribosome engineering, mutation of the ribosomal protein S12 (an essential component of the ribosomal 30S subunit) at K88 enhances protein synthesis and a mutation at RNAP at H437 increases the promoter binding affinity in stationary growth phase. This led to the expression of bacterial silent gene cluster and the production of antibiotic piperidamycins.

The COMPASS (complex associated with Set 1) complex has been shown to be responsible for the methylation of lysine 4 on histone 3 (H3K4) in yeast. Deletion of the cclA gene in A. nidulans, encoding one of the eight COMPASS complex proteins, led to the activation of at least two silent gene clusters that involved in the biosynthesis of emodin and the related compounds, monodictyphenone, and F9775A/F9775B (Figure 1a) [16]. Besides the acetylation and methylation of histones, deletion of the single sumoylation gene sumO in A. nidulans caused a dramatic increase in asperthecin and a decrease of austinol/dehydroaustinol and sterigmatocystin production [17]. Although the precise mechanism by which epigenetic regulation affects secondary metabolite production still awaits elucidation, the examples above confirm the applicability of using epigenetic modifiers for modulating secondary metabolite production. Moreover, the Cichewicz group was able to obtain novel fungal natural products using a similar concept by culturing a fungus in the presence of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) or HDAC inhibitors [18]. This chemical epigenetic mining does not require genetic manipulation, and it thus can be applied to many cultivable fungal strains.

Heterologous expression of secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters

Transcription factor promoter replacement and targeting of genes involved in chromatin-level regulation of gene expression can only be carried out in organisms with well-developed molecular genetic systems. To use such approaches with gene clusters in other organisms, either a good molecular genetic system has to be developed for that organism or secondary metabolism genes or gene clusters from the organism have to be introduced into appropriate heterologous host organisms. Because PKS- and NRPS-containing gene clusters can be very large in size, however, introducing these clusters into heterologous hosts can be quite technically challenging and time-consuming. In addition, it may be necessary to replace the native promoters of the genes that one is attempting to express with a strong or inducible promoter that functions in the host organism. If there are a large number of genes in the pathway, this could be quite difficult.

This approach has the advantage, however, that if a cluster is introduced into a host organism, and a new metabolite appears, one can ascribe it with confidence to the cluster. An interesting example that combines heterologous expression and cluster specific activation has been published by the Nihira group [19]. They engineered a citrinin-producing A. oryzae strain by introducing the entire citrinin biosynthetic gene cluster from Monascus purpureus into A. oryzae followed by heterologous expression of the citrinin cluster specific activator ctnA. This approach could potentially be used for the determination of other silent gene clusters in filamentous fungi.

Inter-species crosstalk

It is generally accepted that one of the roles of secondary metabolites is to provide a biological advantage for the producer in response to its environment. In some cases secondary metabolites may protect against non-biological agents such as ultraviolet radiation, but in many cases they will be used to compete against other organisms. Use of secondary metabolites to compete with other organisms implies that there must be some sort of sensing mechanism to control production of the metabolites. It follows that by harnessing the interplay between the producer and the environment, it might be possible to stimulate silent clusters to produce secondary metabolites. Schroeck et al. employed a microarray-based approach to monitor the selective activation of silent fungal biosynthetic genes via bacterial-fungal interaction [20]. Using a collection of 58 actinomycetes, Schroeck et al. discovered that when A. nidulans is co-cultured with Streptomyces rapamycinicus, two secondary metabolite genes clusters are induced (Figure 1b). One of the gene clusters produced the aromatic polyketides orsellinic acid, lecanoric acid and the cathepsin K inhibitors F-9775A/F-9775B. Interestingly, dialysis experiments and electron microscopy indicated that a physical contact of the S. rapamycinicus and A. nidulans is required to elicit expression of the silent PKS gene. This study provides evidence that physical interaction among microorganisms can lead to the induction of silent biosynthesis genes. It also demonstrates the potential of using mixed-cultivation of microorganisms for novel secondary metabolite discovery.

Ribosome engineering in prokaryotes

Great efforts have been committed to improving the yield of antibiotics in microorganisms, primarily to meet commercial requirements and demands. The Ochi group developed a method, termed “ribosome engineering”, to increase antibiotic production by targeting ribosomal protein S12 or RNA polymerase (RNAP), with the idea that bacterial gene expression may be increased dramatically by altering transcription and translation machineries (Figure 1c) [21]. Since many antibiotics, such as streptomycin, target the ribosome, ribosome mutants that confer antibiotic resistance could be obtained by simply selecting for mutants on streptomycin-containing plates. Similarly, RNAP mutants could be obtained by growing on plates containing rifampicin, which binds to RNAP and inhibits RNA synthesis. Remarkably, these mutants not only had increased antibiotic production but were found to produce novel antibiotics [22]. After screening of 1,068 actinomycetes isolated from soil, 6% of non-Streptomyces actinomycetes species and 43% of Streptomyces species that did not produce antibacterials were activated to produce them. A mechanistic study indicated that the effect observed was due to a mutation at Lys-88 to either Glu or Arg in the ribosomal protein S12, which enhances protein synthesis in stationary growth phase. In addition, a mutation at His-437 to either Asp or Leu in the RNAP β-subunit increased its promoter binding affinity. Similar to co-culture and epigenetic mining approaches, such a “ribosome engineering” approach triggers the activation of one or several but not all biosynthesis clusters in the organism. However, these approaches, unlike the approaches that activate pathway-specific activators, do not trigger specific biosynthetic gene clusters.

Linking orphan clusters to molecules

Several orphan biosynthetic gene clusters have been identified by gene inactivation combined with comparative metabolic profiling ([2,7] and the references cited therein). However, several novel strategies that do not require genetic manipulation of the producing organism have been introduced recently. They rely on the lesson learned from known biosynthetic pathways and from developments in bioinformatics and proteomics.

Genomisotopic approach

The Loper and Gerwick groups reported an approach they term the “genomisotopic approach” in which isotope-labeled precursors are fed to a genome-sequenced microorganism followed by isotope-guided fractionation (Figure 2a) [23]. This approach takes advantage of the fact that the amino acid substrate that will be used by the adenylation (A) domain of bacterial NRPSs can be predicted from the amino acid sequences of the domain by bioinformatics [24]. Leucine, for example, was predicted to be incorporated at four different A domains in the ofa cluster, an orphan gene cluster of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. 15N-L-leucine was subsequently fed into cultures of this organism early in the exponential growth phase. Because 15N-L-leucine can be readily detected by 1H-15N HMBC NMR experiments, the major product of ofa cluster, orgamide A, was identified and isolated by isotope-guided fractionation. The strength of the genomisotopic approach lies in its potential for rapid isolation of novel metabolites without the need for any genetic manipulation. However, this approach requires that the biosynthetic gene cluster be expressed at adequate levels. If it is poorly expressed or not expressed at all, OSMAC or other approaches must be used to activate the cluster.

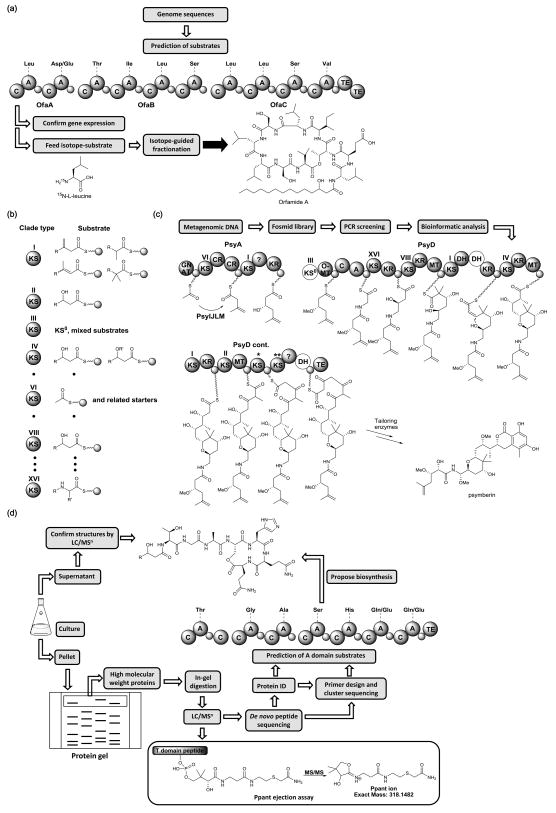

Figure 2.

Linking orphan clusters to molecules. (a) Flowchart of the “genomisotopic approach” for the isotope-guided isolation of orfamide A biosynthesized from the ofa gene cluster. C, condensation domain; A, adenylation domain; TE, thioesterase domain; small circles symbolize the thiolation (T) domain. (b) Phylogeny of trans-AT KS domains, KS domains that accept similar substrates fall into the same clade type. (c) Cloning of the psy gene cluster and the elucidation of its biosynthetic pathway from a highly complicated metagenome by the chemical structure-based gene targeting approach. The KS with one asterisk is rare and no clade exists so far. The KS with two asterisks falls into the cis-AT group. Domains shown in white lack conserved catalytic residues and are non-functional. For the abbreviation for each domain, see reference [27]. (d) Flowchart of PrISM for the identification of robustly expressed NRPSs. The high molecular weight proteins from microbial cultures are subjected to in-gel digestion and proteomics analysis by LC/MSn. Peptides that contain Ppant arms can be traced by the Ppant ejection assay. Peptide sequences obtained from de novo peptide sequencing are used to design degenerate primers to amplify regions of the expressed gene cluster. The A domains of the identified NRPS cluster are used to predict the substrates of amino acid incorporated. The metabolites with the predicted amino acid sequences are ultimately confirmed by LC/MSn in the culture supernatant.

Gene-directed or chemical structure-based gene targeting

Even though the genomes of many natural-product-producing organisms have now been sequenced, the genomes of the vast majority of organisms have not been sequenced. In many cases, including many marine sponges, the producing microorganism is not known or is unculturable in the lab. In these instances, gene cloning guided by specific gene sequences and/or chemical structures can, in principle, provide a solution. Examples of screening for new derivatives of pharmacologically important natural products include the search for new enediynes by targeting a specific PKS encoding the “warhead” chromophore [25], and the search for new vancomycin- and teicoplanin-like glycopeptides by searching for the specific enzyme, OxyC, that catalyzes the C-C bond formation between the hydroxyphenylglycine and the dihydroxyphenylglycine groups [26]. Recently, the Piel group impressively demonstrated an extension of this approach in the search for the biosynthetic gene cluster of psymberin (Figure 2c), a highly potent antitumor agent that is produced from a marine sponge, but at extremely low yields [27]. Sponges harbor a number of symbionts and sequencing of DNA from a sponge harvested in the wild yields a metagenome, containing sequences from the sponge and its symbionts. The Piel group took advantage of the fact that phylogenetic studies suggest that it is possible to differentiate trans-AT KS domains from cis-AT systems. Moreover, the substrate of trans-AT KS domains can be uniquely predicted by bioinformatic analysis (Figure 2b) [28]. In other words, similar trans-AT KS domains process similar substrates. KS phylogeny of the trans-AT system, thus, provides detailed information about the polyketide structure, and does not require any knowledge about other PKS domains. In the Piel group’s study, diverse KS amplicon mixtures were first generated by degenerate KS primers from the complicated metagenome of a marine sponge. Subsequently, PCR with degenerate nested primers that target the specific clade of trans-AT KS predicted from the chemical structure of psymberin was used to clone the psymberin KS domains. Using this strategy, the entire psymberin gene cluster (Figure 2c) was identified after screening of more than 400,000 fosmid clones by a pooling strategy in a three-dimensional format [29]. The success of this approach relies on first, the previous finding that the substrate of trans-AT KS domains can be predicted by KS phylogeny, and second, the ability to design primers that target specific trans-AT KS domains.

Proteomics approaches

Proteomic approaches have become an important tool in the identification of orphan clusters. The Brakhage group elucidated pyomelanin formation in A. fumigatus by comparing protein profiles in pyomelanin-producing and nonproducing conditions [30]. Proteins upregulated in pyomelanin-producing conditions are good candidates for being involved in pyomelanin biosynthesis. More sophisticated methodology, termed PrISM (Proteomic Investigation of Secondary Metabolism), has been developed by the Kelleher group (Figure 2d) [31]. This method identifies robustly expressed megasynthases without the requirement for genome sequence information a priori. By exploiting the fact that PKSs and NRPSs are high molecular weight proteins (often > 200 kDa), high molecular bands from protein gels were subjected to proteomic analysis by high resolution tandem mass spectrometry (MSn). The unique “top down” ions derived from the phosphopantetheinyl (Ppant) arm in the carrier protein domains of PKSs or NRPSs were then accurately traced by the Ppant ejection assay [32]. A Bacillus strain, NK2018, isolated from environment with no DNA sequence information was analyzed. By combining the de novo peptide sequencing using LC/MSn and bioinformatics analysis of the high molecular weight proteome from NK2018, a novel NRPS cluster that is an ortholog to the predicted cluster from Bacillus cereus AH1134 genome was identified. The DNA sequences of this cluster in NK2018 were ultimately determined to be > 94% identical to B. cereus AH1134. Several putative lipoheptapeptides that matched the predicted substrates of A domains of this novel NRPS cluster were then identified from the NK2018 culture supernatant. This “protein first” approach thus complements genome mining approaches in that it does not reveal which gene clusters are actually expressed. Besides the PrISM approach, several fluorescent and biotinylated probes targeting carrier protein or thioesterase domains in PKS and NRPS have also been developed by the Burkart group [33,34]. These probes, combined with proteomics methodologies, offer valuable tools for comparative profiling of the biosynthesis capabilities as well as identification of orphan pathways in microorganisms.

Conclusions

With various exciting new tools introduced in recent years, natural product research has now entered a new promising age. Development of new expression hosts including new selection markers and inducible promoters will allow more gene clusters to be successfully expressed in heterologous expression systems. Understanding the signaling cascades from inter-species crosstalk, and the regulation at the transcription and translation levels will facilitate the discovery of additional silent natural products. Bioinformatics will likely play an ever-increasing role as more and more orphan gene clusters are linked to their cognate metabolites. The ultimate goal will be to predict natural products from unknown gene clusters using genome sequencing information.

Proteomics is also beginning to fill the gap in the identification of orphan clusters. With the development of an increasingly powerful reparatory of tools, there is every prospect that cryptic biosynthetic pathways will become invaluable resources for new therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

Research in the Wang and Oakley Groups is supported in part by PO1-GM084077 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The Oakley group is additionally supported by the University of Kansas endowment fund. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Scherlach K, Hertweck C. Triggering cryptic natural product biosynthesis in microorganisms. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:1753–1760. doi: 10.1039/b821578b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross H. Strategies to unravel the function of orphan biosynthesis pathways: recent examples and future prospects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;75:267–277. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0900-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Assembly-line enzymology for polyketide and nonribosomal Peptide antibiotics: logic, machinery, and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3468–3496. doi: 10.1021/cr0503097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh CT, Fischbach MA. Natural products version 2.0: connecting genes to molecules. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2469–2493. doi: 10.1021/ja909118a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hertweck C. The biosynthetic logic of polyketide diversity. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:4688–4716. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiang YM, Lee KH, Sanchez JF, Keller NP, Wang CC. Unlocking fungal cryptic natural products. Nat Prod Commun. 2009;4:1505–1510. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zerikly M, Challis GL. Strategies for the discovery of new natural products by genome mining. Chembiochem. 2009;10:625–633. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brakhage AA, Schroeckh V. Fungal secondary metabolites - Strategies to activate silent gene clusters. Fungal Genet Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hertweck C. Hidden biosynthetic treasures brought to light. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:450–452. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0709-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bode HB, Bethe B, Hofs R, Zeeck A. Big effects from small changes: possible ways to explore nature’s chemical diversity. Chembiochem. 2002;3:619–627. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020703)3:7<619::AID-CBIC619>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11**.Bergmann S, Schumann J, Scherlach K, Lange C, Brakhage AA, Hertweck C. Genomics-driven discovery of PKS-NRPS hybrid metabolites from Aspergillus nidulans. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:213–217. doi: 10.1038/nchembio869. This study shows that ectopic overexpression of a regulator within the biosynthetic gene cluster results in the concerted activation of the whole gene cluster. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiang YM, Szewczyk E, Davidson AD, Keller N, Oakley BR, Wang CC. A gene cluster containing two fungal polyketide synthases encodes the biosynthetic pathway for a polyketide, asperfuranone, in Aspergillus nidulans. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2965–2970. doi: 10.1021/ja8088185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimizu K, Hicks JK, Huang TP, Keller NP. Pka, Ras and RGS protein interactions regulate activity of AflR, a Zn(II)2Cys6 transcription factor in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics. 2003;165:1095–1104. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.3.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bok JW, Hoffmeister D, Maggio-Hall LA, Murillo R, Glasner JD, Keller NP. Genomic mining for Aspergillus natural products. Chem Biol. 2006;13:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shwab EK, Bok JW, Tribus M, Galehr J, Graessle S, Keller NP. Histone deacetylase activity regulates chemical diversity in Aspergillus. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:1656–1664. doi: 10.1128/EC.00186-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16**.Bok JW, Chiang YM, Szewczyk E, Reyes-Domingez Y, Davidson AD, Sanchez JF, Lo HC, Watanabe K, Strauss J, Oakley BR, et al. Chromatin-level regulation of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:462–464. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.177. This report revealed that silent biosynthetic gene clusters are activated by the disruption of the COMPASS complex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17*.Szewczyk E, Chiang YM, Oakley CE, Davidson AD, Wang CC, Oakley BR. Identification and characterization of the asperthecin gene cluster of Aspergillus nidulans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:7607–7612. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01743-08. This report shows that sumoylation alters secondary metabolite profiles. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18*.Williams RB, Henrikson JC, Hoover AR, Lee AE, Cichewicz RH. Epigenetic remodeling of the fungal secondary metabolome. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:1895–1897. doi: 10.1039/b804701d. This report shows silent secondary metabolites can be induced by a chemical epigenetic mining approach. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19*.Sakai K, Kinoshita H, Shimizu T, Nihira T. Construction of a citrinin gene cluster expression system in heterologous Aspergillus oryzae. J Biosci Bioeng. 2008;106:466–472. doi: 10.1263/jbb.106.466. This is the first report that combines the heterologous expression and induction of a regulator within the biosynthetic gene cluster. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20*.Schroeckh V, Scherlach K, Nutzmann HW, Shelest E, Schmidt-Heck W, Schuemann J, Martin K, Hertweck C, Brakhage AA. Intimate bacterial-fungal interaction triggers biosynthesis of archetypal polyketides in Aspergillus nidulans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14558–14563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901870106. The first study that demonstrates that physical interactions contribute to the communication among microorganisms and induction of silent biosynthetic gene clusters. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ochi K, Okamoto S, Tozawa Y, Inaoka T, Hosaka T, Xu J, Kurosawa K. Ribosome engineering and secondary metabolite production. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2004;56:155–184. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(04)56005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22**.Hosaka T, Ohnishi-Kameyama M, Muramatsu H, Murakami K, Tsurumi Y, Kodani S, Yoshida M, Fujie A, Ochi K. Antibacterial discovery in actinomycetes strains with mutations in RNA polymerase or ribosomal protein S12. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:462–464. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1538. An important strategy to induce antibiotic biosynthesis. This report provides the mechanistic study of ribosome engineering that could potentially activate silent gene clusters. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23*.Gross H, Stockwell VO, Henkels MD, Nowak-Thompson B, Loper JE, Gerwick WH. The genomisotopic approach: a systematic method to isolate products of orphan biosynthetic gene clusters. Chem Biol. 2007;14:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.11.007. A study that demonstrates that the isotope-labeled precursor predicted from A domains of NRPS can be used to identify the metabolites of the orphan gene cluster. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rausch C, Weber T, Kohlbacher O, Wohlleben W, Huson DH. Specificity prediction of adenylation domains in nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) using transductive support vector machines (TSVMs) Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5799–5808. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu W, Ahlert J, Gao Q, Wendt-Pienkowski E, Shen B, Thorson JS. Rapid PCR amplification of minimal enediyne polyketide synthase cassettes leads to a predictive familial classification model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11959–11963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2034291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banik JJ, Brady SF. Cloning and characterization of new glycopeptide gene clusters found in an environmental DNA megalibrary. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17273–17277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807564105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27**.Fisch KM, Gurgui C, Heycke N, van der Sar SA, Anderson SA, Webb VL, Taudien S, Platzer M, Rubio BK, Robinson SJ, et al. Polyketide assembly lines of uncultivated sponge symbionts from structure-based gene targeting. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:494–501. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.176. An excellent study that shows that the genes responsible for synthesis of complex marine natural products produced from trans-AT PKS can be cloned from highly complex metagenomic DNA by structure-based gene targeting. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28**.Nguyen T, Ishida K, Jenke-Kodama H, Dittmann E, Gurgui C, Hochmuth T, Taudien S, Platzer M, Hertweck C, Piel J. Exploiting the mosaic structure of trans-acyltransferase polyketide synthases for natural product discovery and pathway dissection. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:225–233. doi: 10.1038/nbt1379. An important study that highlights the chemical structural information of trans-AT PKS is encoded in the trans-AT KS domain, thus, providing new strategies for dissecting polyketide biosynthetic pathways. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hrvatin S, Piel J. Rapid isolation of rare clones from highly complex DNA libraries by PCR analysis of liquid gel pools. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;68:434–436. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmaler-Ripcke J, Sugareva V, Gebhardt P, Winkler R, Kniemeyer O, Heinekamp T, Brakhage AA. Production of pyomelanin, a second type of melanin, via the tyrosine degradation pathway in Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:493–503. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02077-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31**.Bumpus SB, Evans BS, Thomas PM, Ntai I, Kelleher NL. A proteomics approach to discovering natural products and their biosynthetic pathways. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:951–956. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1565. PrISM, a protein first strategy that combines proteomics, bioinformatics and the property of megasynthase to elucidate expressed orphan biosynthetic gene clusters. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorrestein PC, Bumpus SB, Calderone CT, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Aron ZD, Straight PD, Kolter R, Walsh CT, Kelleher NL. Facile detection of acyl and peptidyl intermediates on thiotemplate carrier domains via phosphopantetheinyl elimination reactions during tandem mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12756–12766. doi: 10.1021/bi061169d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meier JL, Mercer AC, Burkart MD. Fluorescent profiling of modular biosynthetic enzymes by complementary metabolic and activity based probes. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5443–5445. doi: 10.1021/ja711263w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34*.Meier JL, Niessen S, Hoover HS, Foley TL, Cravatt BF, Burkart MD. An orthogonal active site identification system (OASIS) for proteomic profiling of natural product biosynthesis. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:948–957. doi: 10.1021/cb9002128. A valuable pulldown-based tool for PKS and NRPS profiling by labeling carrier protein and thioesterase domains. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]