Abstract

We have attempted to determine whether loss of mtDNA and respiratory chain function result in apoptosis in vivo. Apoptosis was studied in embryos with homozygous disruption of the mitochondrial transcription factor A gene (Tfam) and tissue-specific Tfam knockout animals with severe respiratory chain deficiency in the heart. We found massive apoptosis in Tfam knockout embryos at embryonic day (E) 9.5 and increased apoptosis in the heart of the tissue-specific Tfam knockouts. Furthermore, mtDNA-less (ρ0) cell lines were susceptible to apoptosis induced by different stimuli in vitro. The data presented here provide in vivo evidence that respiratory chain deficiency predisposes cells to apoptosis, contrary to previous assumptions based on in vitro studies of cultured cells. These results suggest that increased apoptosis is a pathogenic event in human mtDNA mutation disorders. The finding that respiratory chain deficiency is associated with increased in vivo apoptosis may have important therapeutic implications for human disease. Respiratory chain deficiency and cell loss and/or apoptosis have been associated with neurodegeneration, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and aging. Furthermore, chemotherapy and radiation treatment of cancer are intended to induce apoptosis in tumor cells. It would therefore be of interest to determine whether manipulation of respiratory chain function can be used to inhibit or enhance apoptosis in these conditions.

The mitochondrial respiratory chain provides most cellular energy, and respiratory chain dysfunction is found in a genetically heterogeneous group of patients with neuromuscular, cardiac, or endocrine syndromes. Deficient respiratory chain function has also been implicated in common human disorders, such as diabetes mellitus, heart failure, and neurodegeneration, and in the normally occurring aging process. Recent development in the area of apoptosis research has demonstrated that mitochondria are key regulators of critical signaling events in programmed cell death. Mitochondria may induce apoptosis by releasing cytochrome c from the intermembrane space to the cytosol. In the presence of ATP, cytosolic cytochrome c interacts directly with apoptotic protease activating factor 1 and procaspase 9 to form the apoptosome, a macromolecular complex that cleaves procaspase 9 to active caspase 9 (1), which, in turn, cleaves procaspase 3 to active caspase 3. Apoptosis can be further induced by activation of death receptors. Binding of extracellular ligands, such as Fas ligand or tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), to their respective receptors induces receptor trimerization, which, in turn, recruits adaptor molecules, e.g., Fas receptor-associated death domain protein and TNF receptor-associated death domain protein, and procaspase 8. This signaling complex activates procaspase 8, and downstream events include activation of procaspase 3 and cytochrome c release mediated by cleavage of Bid (2, 3). Both the mitochondrial and the death receptor pathways thus converge on cleavage of procaspase 3, resulting in DNA fragmentation after activation of caspase-activated deoxyribonuclease or DNA fragmentation factor (4–6). Finally, it has been demonstrated that mitochondria also release other proteins during apoptosis, e.g., apoptosis-inducing factor, which does not activate caspases but translocates directly to the nucleus and induces DNA fragmentation (7), and the second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase protein, which blocks the inhibitors of apoptosis proteins that inhibit caspases (8). It is currently not known whether deficient respiratory chain function affects in vivo apoptosis induction. Human cells lacking mtDNA (ρ0 cells) are resistant to in vitro apoptosis induction by staurosporine (STP), suggesting that respiratory chain function is required for apoptosis (9). Knockout mouse cells lacking cytochrome c cannot induce the mitochondrial pathway for apoptosis and are more sensitive to death receptor-induced apoptosis (10). The phenotypes observed in these cells may be due to an absence of releasable mitochondrial cytochrome c, respiratory chain deficiency, or a combination of these two factors. In this paper we have investigated apoptosis in mouse embryos that lack Tfam and, as a consequence, have a severe respiratory chain deficiency and in tissue-specific Tfam knockout mice with severe respiratory chain deficiency in the heart. We have also reinvestigated the ability of human cell lines lacking mtDNA to undergo apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Samples.

Heart samples from Tfam heart knockouts (TfamloxP/TfamloxP, +/Ckmm-cre)(11) and their littermate controls (TfamloxP/TfamloxP) were collected at 2–3 weeks of age. Homozygous Tfam knockout embryos (Tfam−/−) were obtained by matings between germline heterozygous Tfam knockout animals (Tfam+/−) (12). The samples were immediately embedded in OCT Tissue-Tek (Sakura, Zoetenwoude, The Netherlands) and kept at −70°C until further use.

Cell Lines.

A human osteosarcoma-derived cell line, 143B, containing mtDNA (ρ+), and its mtDNA-less derivative, 143B/206 (ρ0) (13), were maintained in DMEM-high glucose (1000 mg/liter; GIBCO/BRL, Life Technologies, Täby, Sweden) containing 10% FBS and 100 IU/ml penicillin-streptomycin (GIBCO/BRL, Life Technologies). The 143B/206 ρ0 cells were additionally supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate (GIBCO/BRL, Life Technologies) and 50 μg/ml uridine (Sigma–Aldrich) as described (13).

Cytotoxicity Assays.

Cells were incubated for 16 h at 37°C with medium containing: (i) 0.5 μM STP (Sigma–Aldrich); (ii) 100 ng/ml human anti-Fas antibody (MBL, Nagoya, Japan) plus 100 ng/ml actinomycin D (Sigma–Aldrich); and (iii) 20 ng/ml human recombinant TNFα (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) plus 100 ng/ml actinomycin D. Cells were pretreated with 100 ng/ml actinomycin D for 15 min at 37°C before the addition of TNFα plus actinomycin D or anti-Fas antibody plus actinomycin D.

Flow Cytometric Analyses of Apoptotic Cells.

We stained the cells with annexin V and propidium iodide with the use of the Vybrant apoptosis assay kit 2 (Molecular Probes). Flow cytometric analyses were performed on a Becton Dickinson flow cytometer (FACScan), and the results were analyzed with the cell quest program (Becton Dickinson). Annexin V/propidium iodide measurements were performed on ρ0 and ρ+ cells incubated with 0.5 μM STP (n = 3), 100 ng/ml human anti-Fas antibody plus 100 ng/ml actinomycin D (n = 4), and 20 ng/ml human recombinant TNFα plus 100 ng/ml actinomycin D (n = 4) for 16 h.

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyltransferase-Mediated dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) Assay.

Cryostat tissue sections of hearts or embryos and slides with tissue culture cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. TUNEL staining was carried out with the Apoptag Peroxidase Kit (Invitrogen). Sections were counterstained with Methyl Green (Dako). Areas of heart sections were measured with the National Institutes of Health image 1.41 program (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image). TUNEL-positive cells on the whole section were counted, and the apoptotic index was calculated as the number of TUNEL-positive cells per mm2. TUNEL stainings were performed on heart sections from 2- to 3-week-old Tfam heart knockouts (n = 15) and littermate controls (n = 15) and from Tfam knockout embryos (Tfam−/−) and littermate control embryos at E8.5 (n = 3) and E9.5 (n = 4).

DNA Ladder Assay.

Tissues and cells were incubated for 3 h at 50°C in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0)/0.1 M NaCl/2.5 mM EDTA/0.5% SDS/200 μg/ml proteinase K). DNA was isolated with chloroform extraction and treated with 1 μg/ml DNase-free RNase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) for 1 h at room temperature. DNA samples (10–20 μg) were separated by electrophoresis in a 1.8% agarose gel. The gel was stained with SYBR Green I nucleic acid gel stain (Molecular Probes) after electrophoresis, and the DNA was visualized under UV light.

Measurement of Caspase 3 Activity.

Caspase 3 activity was measured with a caspase 3 assay kit (PharMingen). Briefly, a tetrapeptide labeled with the fluorochrome 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin was used as a substrate to identify and quantitate caspase 3 activity. 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin is released from the substrate on cleavage by caspase-3. Free 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin is quantified in cell lysates by UV light at an excitation wavelength of 365 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm. The fluorometric count was normalized by the protein concentration of the supernatant. Caspase 3 activity was measured on ρ0 and ρ+ cells incubated with 0.5 μM STP (n = 3), 100 ng/ml human anti-Fas antibody plus 100 ng/ml actinomycin D (n = 3), and 20 ng/ml human recombinant TNFα plus 100 ng/ml actinomycin D (n = 3) for 16 h.

Northern Blot.

RNA from heart samples was isolated with the Trizol Reagent (GIBCO/BRL, Life Technologies). Reverse transcription–PCR products were separated on gels, purified with the QIAEX II gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Germany), radiolabeled with α-32P, and used as probes to detect glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, atrial natriuretic factor, sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase2, Bcl-x(L), Bax, glutathione peroxidase (Gpx), and mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (Sod2) transcripts. The intensities of signals were recorded with a FUJIX Bio-Imaging Analyzer BAS 1000 (Fuji), and data were analyzed with the image gauge V3.3 program (Fuji). The loading was normalized to 18S rRNA.

Histology and Biochemistry.

Cryostat tissue sections from hearts or embryos and slides with tissue culture cells were fixed for 10 min at room temperature in phosphate-buffered 1% paraformaldehyde followed by permeabilization in ice-cold acetic acid/ethanol for 5 min. We used polyclonal antisera against (i) cleaved caspase 3 (cell signaling technology; New England Biolabs); (ii) cleaved caspase 7 (cell signaling technology; New England Biolabs); and (iii) p53 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). We incubated the sections with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight at the recommended dilutions and used Dako Envision TM (Dako) as a secondary antibody. Immunohistochemical stainings to detect cleaved caspase 3 and 7 were performed on heart sections from Tfam heart knockouts (n = 4–7) and littermate controls (n = 4–7) and from E9.5 Tfam knockout (n = 4) and control embryos (n = 4). Immunohistochemical stainings to detect p53 were carried out on heart sections from Tfam heart knockouts (n = 3) and littermate controls (n = 3). Enzyme histochemical stainings to detect cytochrome c oxidase (COX) and succinate dehydrogenase activity were performed on cryostat sections as described (12). Biochemical measurements of enzyme activities were performed on hearts from Tfam heart knockouts (n = 8) and littermate controls (n = 8) as described (14, 15).

Western Blots.

Total protein extracts were prepared and Western blots were performed as described (11). The primary antibodies reacted with p53 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), cleaved caspase 3 (cell signaling technology; New England Biolabs), and the δ isoform of protein kinase C (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Results

Cardiomyocytes with Impaired Oxidative Phosphorylation Are More Prone To Undergo Apoptosis Than Normal Cardiomyocytes.

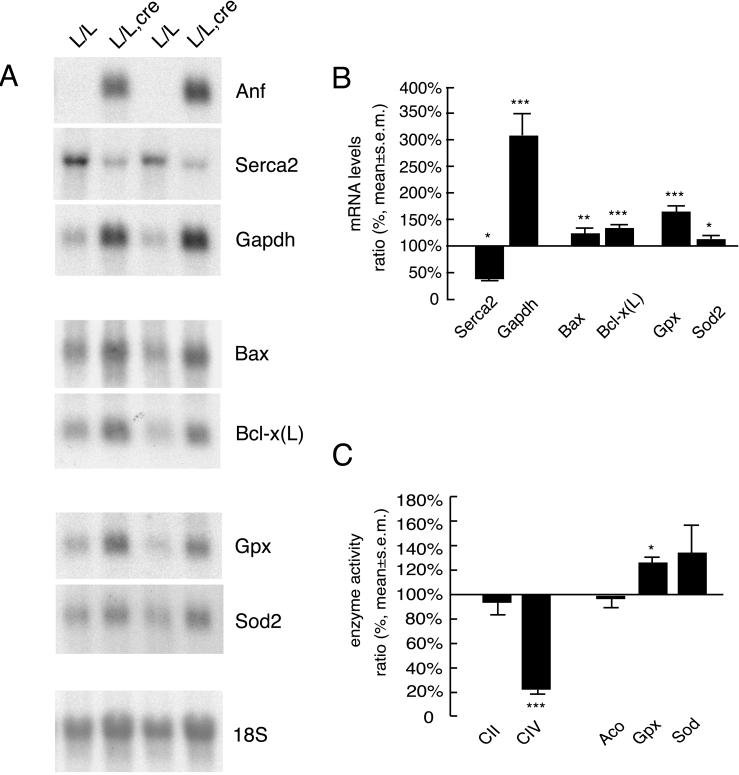

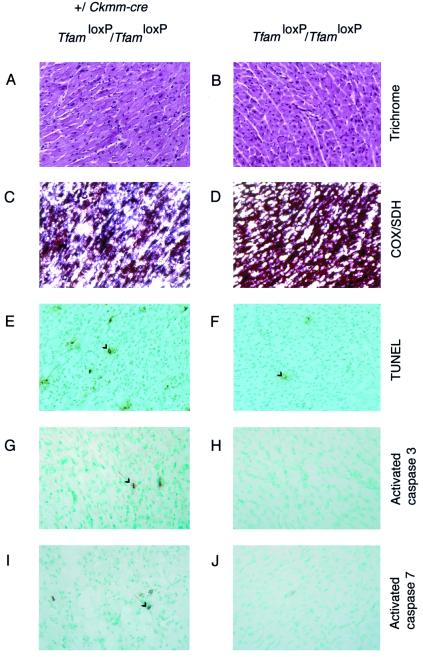

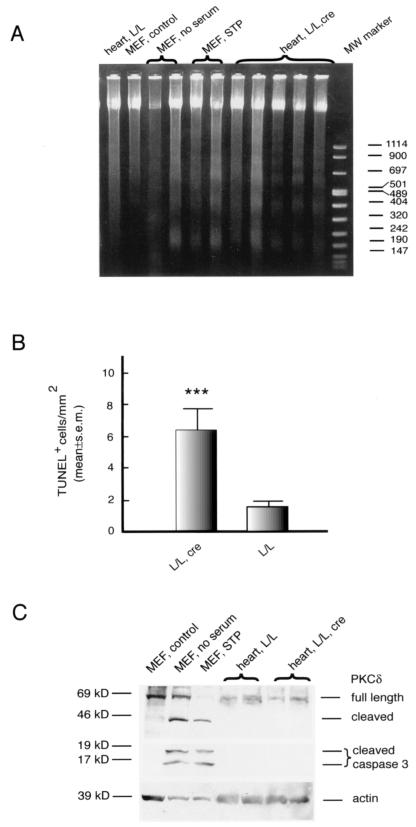

We performed additional studies of the previously characterized transgenic mouse model with tissue-specific Tfam gene disruption causing postnatal onset of severe mitochondrial cardiomyopathy (11). Northern blots demonstrated increased levels of the transcripts for the glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and atrial natriuretic factor (Fig. 1 A and B). Levels of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase2 transcripts were reduced (Fig. 1 A and B). These changes in atrial natriuretic factor and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase2 gene expression are typically found in animals and humans with heart failure (16, 17). Histological analyses of Tfam knockout hearts showed no evidence of fibrosis, necrosis, or inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig. 2 A and B). Enzyme histochemical stainings confirmed previous results (11) and showed a mosaic respiratory chain deficiency in the myocardium (Fig. 2 C and D). TUNEL staining of heart sections demonstrated a significantly increased frequency of TUNEL-positive cells in the Tfam knockout hearts (Figs. 2 E and F and 3B). The TUNEL assay is not considered to be specific for apoptosis (18). Therefore, we performed DNA ladder gel assays, which showed significant DNA fragmentation in 5 of 12 investigated Tfam knockout hearts (Fig. 3A). Immunohistochemical analyses detected cardiomyocytes expressing activated caspase 3 and 7 in the Tfam knockout hearts (Fig. 2 G and I) but not in control hearts (Fig. 2 H and J). Western blot analyses could detect cleavage of caspase 3 and cleavage of δ isoform of protein kinase C, a substrate of active caspase 3, in serum-starved or STP-treated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), but not in the Tfam knockout hearts (Fig. 3C). Northern blots of RNA from Tfam knockout hearts showed increased levels of transcripts encoding the proapoptotic Bax and the anti-apoptotic Bcl-x(L) proteins (Fig. 1 A and B), demonstrating increased expression of genes regulating apoptosis. Taken together, these findings are consistent with increased apoptosis in the Tfam knockout hearts but do not provide information about the activated pathway.

Figure 1.

Gene expression profiles and enzyme activities in hearts of Tfam heart knockouts (TfamloxP/TfamloxP, +/Ckmm-cre) and littermate controls (TfamloxP/TfamloxP). (A) Northern blots showing mRNA expression of atrial natriuretic factor (Anf), sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase2 (Serca2), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh), Bax, Bcl-x(L), glutathione peroxidase (Gpx), and mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (Sod2) in Tfam knockout hearts (L/L, cre) and control hearts (L/L). The nuclear 18S rRNA transcript was used as a loading control. (B) Results from PhosphorImager analyses of gene transcript levels in Tfam knockout (n = 4) and control hearts (n = 4). The relative transcript levels in Tfam knockout hearts in comparison with control hearts are shown. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (C) Biochemical measurements of complex II (CII) and complex IV (CIV), aconitase (Aco), total glutathione peroxidase (Gpx), and total superoxide dismutase (Sod) activities in Tfam knockout (n = 8) and control hearts (n = 8). The relative enzyme activities in Tfam knockout hearts in comparison with control hearts are shown. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Histology of hearts from Tfam heart knockouts (TfamloxP/TfamloxP, +/Ckmm-cre) and their littermate controls (TfamloxP/TfamloxP). Examples of immunoreactive cells are indicated by arrows. Trichrome stainings show no evidence for necrosis or fibrosis in Tfam knockout (A) or control (B) hearts. Double enzyme histochemical stainings for COX activity and succinate dehydrogenase activity show a mosaic loss of COX activity in Tfam knockout hearts, as evidenced by the blue staining of cardiomyocytes (C), and normal COX activity in controls, as reflected by the brown staining of cardiomyocytes (D). TUNEL stainings demonstrate more TUNEL-positive cardiomyocytes in Tfam knockout hearts (E) than in control hearts (F). Immunohistochemical stainings of cleaved caspase 3 and cleaved caspase 7 show occasional positive cardiomyocytes in Tfam knockout hearts (G and I) and no staining in control hearts (H and J).

Figure 3.

Tfam knockout hearts (TfamloxP/TfamloxP, +/Ckmm-cre) show increased apoptosis. (A) DNA ladders can be detected in Tfam knockout hearts (heart, L/L, cre) but not in control hearts (L/L). Serum-starved (no serum) and staurosporine-treated (STP) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) were used as positive controls; untreated MEF (MEF, control) were used as negative controls. (B) Wilcoxon matched-pairs test of results from TUNEL stainings of Tfam knockout hearts (n = 15) and control hearts (n = 15) show a significant increase of TUNEL-positive cells in the Tfam knockout hearts (***, P < 0.001). (C) Detection of cleaved caspase 3 and cleaved δ isoform of protein kinase C (PKCδ) by Western blot analyses. Cleaved caspase 3 and cleaved δ isoform of protein kinase C were not detectable in Tfam knockout hearts (L/L, cre) and control hearts (L/L). Serum-starved (MEF, no serum) and STP-treated MEF (MEF, STP) were used as positive controls, and untreated MEF (MEF, control) were used as negative controls.

Overproduction of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Tfam Knockout Hearts Is Likely Compensated for by the Up-Regulation of Glutathione Peroxidase and Superoxide Dismutase.

The levels of Gpx transcripts (164 ± 28%, P < 0.01) determined by Northern blots and PhosphorImager quantitation (Fig. 1 A and B), as well as the total Gpx enzyme activity (120 ± 18%, P < 0.05) determined by biochemical measurements (Fig. 1C), were elevated in Tfam knockout hearts in comparison with controls. The activities of aconitase, a mitochondrial enzyme reported to be highly sensitive to ROS inactivation (19), and of the nucleus-encoded respiratory chain complex II were not affected in Tfam knockout hearts (Fig. 1C). There were increased levels of Sod2 transcripts (Fig. 1 A and B) and a tendency toward increased total Sod enzyme activity (Fig. 1C). These findings suggest that increased ROS production may be compensated for by induction of Sod and Gpx enzyme activities in the Tfam knockout hearts. Previous studies have shown that p53 protein levels are elevated by oxidative stress (20). We could not detect p53 expression in Tfam knockout hearts by immunohistological staining of tissue sections or by Western blot analysis of total protein and nuclear protein extracts (not shown).

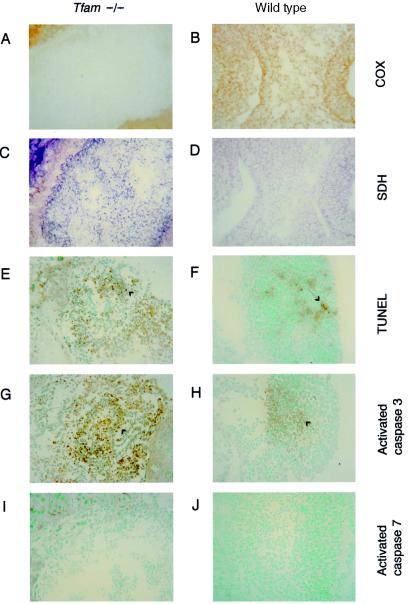

Germline Homozygous Tfam Knockouts Show Massive Apoptosis at E9.5.

We have previously disrupted the gene encoding Tfam in the mouse germline (12), and the resulting Tfam knockout embryos died between E8.5 and E10.5. These Tfam knockout embryos had undetectable levels of mtDNA, no functional respiratory chain (Fig. 4 A–D), and morphologically abnormal mitochondria at E8.5. Only resorbed pregnancies were recovered at E10.5 (12). Further examination of the Tfam knockout embryos showed no increased frequency of TUNEL-positive cells at E8.5 (not shown). However, at E9.5 the Tfam knockout embryos showed abundant TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 4 E and F), and immunohistochemical staining showed increased expression of activated caspase 3 (Fig. 4 G and H) but not of activated caspase 7 (Fig. 4 I and J). These findings demonstrate that massive in vivo apoptosis occurs in respiratory chain-deficient mouse cells lacking mtDNA.

Figure 4.

Massive apoptosis occurred in E9.5 Tfam knockout (Tfam−/−) embryos. All panels illustrate results from embryos at E9.5. Enzyme histochemical staining for COX activity shows no COX activity in Tfam knockout embryos (A) and normal COX activity in control embryos (B). Enzyme histochemical stainings for succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity were normal in Tfam knockout (C) and control embryos (D). TUNEL staining demonstrates abundant TUNEL-positive cells (arrow) in Tfam knockout embryos (E) and a few weakly positive cells in control embryos (F). Immunohistochemical stainings to detect cleaved caspase 3 show abundant positive cells (arrow) in Tfam knockout embryos (G) and occasional positive cells in control embryos (H). Immunohistochemical stainings to detect cleaved caspase 7 are negative in Tfam knockout (I) and control embryos (J).

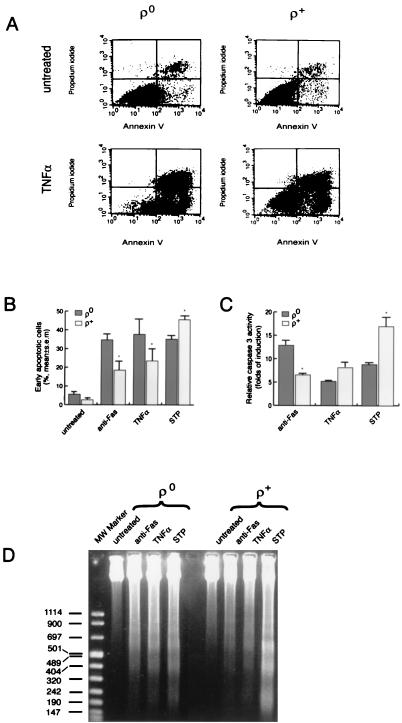

ρ0 Cells Are Susceptible to Apoptosis Induced by Various Signals.

The finding of increased in vivo apoptosis in mouse cells with a severe respiratory chain deficiency apparently contrasted with reports by others showing that human cell lines lacking mtDNA were resistant to STP-induced apoptosis (9). We therefore reinvestigated this issue in human 143B osteosarcoma cells lacking mtDNA. We used flow cytometry of cells stained with annexin V and propidium iodide to determine the number of early apoptotic cells (Fig. 5A). We found more STP-induced apoptosis in cells with mtDNA (ρ+ cells) than in their mtDNA-less derivatives (ρ0 cells; Fig. 5B), consistent with previous reports (9). We further investigated death receptor pathways. Anti-Fas antibody or TNFα had no proapoptotic effect on ρ0 or ρ+ cells. We therefore sensitized the cells with actinomycin D for Fas- and TNFα-mediated apoptosis, as previously described (21, 22). Anti-Fas antibody plus actinomycin D and TNFα plus actinomycin D induced more apoptosis in ρ0 cells than in ρ+ cells (Fig. 5 A and B). Incubation with actinomycin D had a proapoptotic effect on both ρ0 and ρ+ cells, but there were no significant differences in the fraction of apoptotic cells (not shown). We measured caspase 3 activities in ρ0 and ρ+ cells treated with STP, anti-Fas antibody plus actinomycin D, and TNFα plus actinomycin D and found significant induction of caspase 3 activity in both ρ0 and ρ+ cells (Fig. 5C). Activation of caspase 3 in response to these stimuli was further confirmed by Western blots and immunocytochemical stainings of ρ0 and ρ+ cells to detect the active subunits of caspase 3 (not shown). We further demonstrated the presence of DNA ladders in ρ0 and ρ+ cells treated with the same stimuli (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

ρ0 cells are susceptible to apoptosis induced by various signals. ρ0 (143B/206) and ρ+ (143B) osteosarcoma cells were incubated for 16 h with 0.5 μM STP, 100 ng/ml anti-Fas antibody plus 100 ng/ml actinomycin D (anti-Fas), or 20 ng/ml TNFα plus 100 ng/ml actinomycin D (TNFα). (A) Analysis by flow cytometry of apoptotic cells stained with annexin V and propidium iodide to distinguish early apoptotic cells (annexin positive, propidium iodide negative) from late apoptotic or necrotic cells (annexin positive, propidium iodide positive). (B) Susceptibility of ρ0 (143B/206) and ρ+ (143B) osteosarcoma cells to apoptosis in response to various signals as determined by annexin V/propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. Values represent the percentage of early apoptotic (annexin V positive/propidium iodide negative) cells (%). *, P < 0.05. (C) Caspase 3 activities in ρ0 (143B/206) and ρ+ (143B) osteosarcoma cells. The results are plotted as fold induction of caspase 3 activity compared with untreated cells. *P < 0.05. (D) DNA ladders in ρ0 (143B/206) and ρ+ (143B) osteosarcoma cells.

Discussion

Respiratory chain dysfunction contributes to human pathology by affecting cellular energy production and can produce symptoms in almost any organ at almost any age of onset. Cell loss has been documented in the brainstem and pancreatic islets in humans with deficient respiratory chain function. We have recently documented loss of β-cells in mice with β-cell-specific disruption of Tfam (23). It is thus clear that deficient respiratory chain function may cause cell loss in vivo, but the cell loss mechanism has remained elusive.

In this paper we document apoptotic cell death in mouse embryos and mouse hearts with respiratory chain deficiency. In both cases we found a significant increase in TUNEL-positive cells indicative of an active apoptotic process. We further confirmed apoptosis in Tfam knockout hearts by showing DNA fragmentation with gel electrophoresis. We also detected activated caspase 3 in Tfam knockout mouse embryos and activated caspase 3 and activated caspase 7 in Tfam knockout hearts. The respiratory chain deficiency caused a major mutant phenotype (12) in the Tfam knockout embryos without increased apoptosis at E8.5, followed by a massive apoptosis at E9.5 and resorption of the embryo at E10.5. Our findings show that both embryonic and differentiated cells lacking mtDNA can undergo apoptosis in vivo. It is thus possible that apoptosis may contribute significantly to the pathology observed in patients with mtDNA mutation disorders. However, the limited supply of human tissues has been a major drawback to study this phenomenon in humans, and we are aware of only a single report indicating increased apoptosis in human mtDNA mutation disorders (24).

ROS are generally considered to be a potent trigger of apoptosis (25). We found increased Gpx and Sod2 transcript levels and increased Gpx enzyme activity in Tfam knockout mouse hearts. However, mitochondrial aconitase and the nucleus-encoded respiratory chain complex II, both iron-sulfur-containing enzymes whose activities are readily impaired by ROS, had normal activities, suggesting that an induction of antioxidative defenses may eliminate the increased ROS production. Furthermore, we could not detect p53 expression, which has been reported to be induced by oxidative stress (20). The importance of ROS in respiratory chain-deficient cells will have to be investigated in more detail and in other tissues besides heart.

Recent studies have reported that mtDNA-depleted osteosarcoma cells (9) or mouse embryonic cytochrome c knockout cells (10) are less susceptible to apoptosis induction by STP and serum depletion, raising the possibility that respiratory chain function is important for executing apoptosis. We therefore reinvestigated the apoptotic phenotype of cells lacking mtDNA. Our data show that mtDNA-depleted osteosarcoma cells can undergo apoptosis in vitro in response to a variety of signals, i.e., STP and death receptor activation. These findings are in agreement with previous studies carried out on other cell lines lacking mtDNA (9, 26–28).

The cell death mechanism, apoptosis or necrosis, has been shown to depend on intracellular ATP levels (29). ATP depletion blocks nuclear condensation and DNA fragmentation in the final phase of STP- and Fas-induced apoptosis of human T cells (29). We could not detect inflammatory or postinflammatory signs, which were expected to result from necrosis, in Tfam knockout hearts. This result suggests that there is sufficient ATP supply to allow cardiomyocytes to undergo apoptosis, despite the impaired oxidative phosphorylation. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found increased glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase transcript levels indicative of a compensatory up-regulation of glycolysis. It is likely that the respiratory chain deficiency will affect the mitochondrial membrane potential, which, in turn, could make the cells more likely to undergo mitochondrial membrane permeability transition whereby apoptosis-inducing factors are released to the cytosol.

Previous studies have characterized the molecular events involved in the apoptotic response of cell lines with respiratory chain deficiency. When U937 cells lacking mtDNA undergo apoptosis in response to TNFα plus cycloheximide, there is initially decreased mitochondrial membrane potential and increased ROS formation later followed by DNA fragmentation (28). Furthermore, mitochondria isolated from mtDNA-depleted U937 cells can undergo permeability transition with release of apoptogenic factors (28). These results suggest that ρ0 cells are able to induce the mitochondrial pathway for apoptosis. This ability has been further corroborated by studies of mtDNA-depleted osteosarcoma cells demonstrating that cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis is conserved in these cells (27). However, in vitro studies depend on mutant cell lines that are aneuploid, and considerable differences in the karyotype are present in ρ+ and ρ0 cell lines (30). It is thus impossible to conclude from these studies that only the respiratory chain dysfunction influences the susceptibility of different apoptotic pathways. It therefore remains open whether cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis is the main in vivo pathway in cells lacking mtDNA or whether other, cytochrome c-independent pathways may contribute to the apoptotic response. The methods for studying apoptotic pathways in vivo are of limited power, and repeated attempts to establish Tfam knockout cell lines for in vitro studies have failed so far (unpublished data). However, our data provide genetic evidence that respiratory chain-deficient cells are predisposed to undergo apoptosis in vivo.

The finding that respiratory chain deficiency is associated with increased in vivo apoptosis may have important therapeutic implications for human disease. Respiratory chain dysfunction has been suggested to be of pathophysiological importance in a wide variety of common diseases, e.g., neurodegeneration, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and aging. Interestingly, cell loss and/or apoptosis have been described in all of these conditions. Impaired apoptosis is suggested to be of importance for the development of malignant tumors and various hyperproliferative syndromes. Furthermore, chemotherapy and radiation treatment of cancer are intended to induce apoptosis in tumor cells. It is thus possible that manipulation of respiratory chain function may be used to enhance or inhibit apoptosis in a wide variety of conditions.

Acknowledgments

N.-G.L. is supported by grants from the Swedish Medical Research Council (13X-12197, 13P-12204), funds of Karolinska Institutet, the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, Hedlunds Stiftelse, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the Torsten and Ragnar Söderbergs Stiftelse, and the Human Frontiers Science Program. J.P.S. is supported by a stipend from the Roche Research Foundation. P.R. is supported by the Association Françaises contre les Myopathies. C.M.G. is supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society (project 3947) and the Human Frontiers Science Program.

Abbreviations

- E

embryonic day

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- Gpx

glutathione peroxidase

- Sod2

mitochondrial superoxide dismutase

- COX

cytochrome c oxidase

- MEFs

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

References

- 1.Li P, Nijhawan D, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula S M, Ahmad M, Alnemri E S, Wang X. Cell. 1997;91:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagata S. Cell. 1997;88:355–365. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81874-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luo X, Budihardjo I, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X. Cell. 1998;94:481–490. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81589-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakahira H, Enari M, Nagata S. Nature (London) 1998;391:96–99. doi: 10.1038/34214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enari M, Sakahira H, Yokoyama H, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Nagata S. Nature (London) 1998;391:43–50. doi: 10.1038/34112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu X, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X. Cell. 1997;89:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Susin S A, Lorenzo H K, Zamzami N, Marzo I, Snow B E, Brothers G M, Mangion J, Jacotot E, Costantini P, Loeffler M, et al. Nature (London) 1999;397:441–446. doi: 10.1038/17135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du C, Fang M, Li Y, Li L, Wang X. Cell. 2000;102:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dey R, Moraes C T. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7087–7094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li K, Li Y, Shelton J M, Richardson J A, Spencer E, Chen Z J, Wang X, Williams R S. Cell. 2000;101:389–399. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80849-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Wilhelmsson H, Graff C, Li H, Oldfors A, Rustin P, Bruning J C, Kahn C R, Clayton D A, Barsh G S, et al. Nat Genet. 1999;21:133–137. doi: 10.1038/5089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsson N G, Wang J, Wilhelmsson H, Oldfors A, Rustin P, Lewandoski M, Barsh G S, Clayton D A. Nat Genet. 1998;18:231–236. doi: 10.1038/ng0398-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King M P, Attardi G. Science. 1989;246:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.2814477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rotig A, de Lonlay P, Chretien D, Foury F, Koenig M, Sidi D, Munnich A, Rustin P. Nat Genet. 1997;17:215–217. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rustin P, Chretien D, Bourgeron T, Gerard B, Rotig A, Saudubray J M, Munnich A. Clin Chim Acta. 1994;228:35–51. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wankerl M, Schwartz K. J Mol Med. 1995;73:487–496. doi: 10.1007/BF00198900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arai M, Matsui H, Periasamy M. Circ Res. 1994;74:555–564. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanoh M, Takemura G, Misao J, Hayakawa Y, Aoyama T, Nishigaki K, Noda T, Fujiwara T, Fukuda K, Minatoguchi S, et al. Circulation. 1999;99:2757–2764. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.21.2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melov S, Coskun P, Patel M, Tuinstra R, Cottrell B, Jun A S, Zastawny T H, Dizdaroglu M, Goodman S I, Huang T T, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:846–851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye J, Wang S, Leonard S S, Sun Y, Butterworth L, Antonini J, Ding M, Rojanasakul Y, Vallyathan V, Castranova V, et al. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34974–34980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leist M, Gantner F, Bohlinger I, Germann P G, Tiegs G, Wendel A. J Immunol. 1994;153:1778–1788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latta M, Kunstle G, Leist M, Wendel A. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1975–1985. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.11.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva J P, Köhler M, Graff C, Oldfors A, Magnuson M A, Berggren P-O, Larsson N-G. Nat Genet. 2000;26:336–340. doi: 10.1038/81649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirabella M, Di Giovanni S, Silvestri G, Tonali P, Servidei S. Brain. 2000;123:93–104. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green D R, Reed J C. Science. 1998;281:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobson M D, Burne J F, King M P, Miyashita T, Reed J C, Raff M C. Nature (London) 1993;361:365–369. doi: 10.1038/361365a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang S, Cai J, Wallace D C, Jones D P. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29905–29911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marchetti P, Susin S A, Decaudin D, Gamen S, Castedo M, Hirsch T, Zamzami N, Naval J, Senik A, Kroemer G. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2033–2038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leist M, Single B, Castoldi A F, Kuhnle S, Nicotera P. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1481–1486. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.8.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hao H, Morrison L E, Moraes C T. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1117–1124. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.6.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]