Abstract

The ESCRT-0 and ESCRT-I complexes coordinate the clustering of ubiquitinated cargo with intralumenal budding of the endosomal membrane, two essential steps in vacuolar/lysosomal protein sorting from yeast to humans. The 1.85-Å crystal structure of interacting regions of the yeast ESCRT-0 and ESCRT-I complexes reveals that PSDP motifs of the Vps27 ESCRT-0 subunit bind to a novel electropositive N-terminal site on the UEV domain of the ESCRT-I subunit Vps23 centred on Trp16. This novel site is completely different from the C-terminal part of the human UEV domain that binds to P(S/T)AP motifs of human ESCRT-0 and HIV-1 Gag. Disruption of the novel PSDP-binding site eliminates the interaction in vitro and blocks enrichment of Vps23 in endosome-related class E compartments in yeast cells. However, this site is non-essential for sorting of the ESCRT cargo Cps1. Taken together, these results show how a conserved motif/domain pair can evolve to use strikingly different binding modes in different organisms.

Keywords: crystal structure, Cps1, protein structure, vacuole, yeast genetics

Introduction

Eukaryotes share a conserved mechanism for the degradation of damaged, dangerous, or unneeded integral membrane proteins through their ubiquitin-dependent sorting to the lysosome or vacuole (Piper and Luzio, 2007). The endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) complexes are responsible for carrying out this task (Raiborg and Stenmark, 2009). Most of the defining mechanistic studies of this pathway have been carried out in yeast cells (Coonrod and Stevens, 2010) or using yeast proteins, while the physiology has been intensively studied in multicellular organisms. In multicellular organisms and fission yeast, the ESCRT complexes are required for the membrane abscission step in cytokinesis (McDonald and Martin-Serrano, 2009). Moreover, the release of enveloped viruses, including HIV-1, from the plasma membrane of infected human cells requires the ESCRTs in most cases (Morita and Sundquist, 2004; McDonald and Martin-Serrano, 2009).

The process of membrane protein sorting to the lysosome or vacuole can be divided into four steps: clustering of ubiquitinated cargo proteins on endosomes; inward budding of the endosomal membrane; severing of membrane buds to yield intralumenal vesicles (ILVs); and recycling of membrane-bound components to the cytosol (Hurley and Hanson, 2010). The end product of these four steps is the biogenesis of a multivesicular body (MVB) containing the cargo within ILVs. The MVB goes on to fuse with the lysosome or vacuole via the Vps class C protein complexes. These four steps in MVB biogenesis are carried out, respectively, by ESCRT-0 (Piper et al, 1995; Wollert and Hurley, 2010); ESCRT-I and II (Katzmann et al, 2001; Babst et al, 2002b; Wollert and Hurley, 2010); ESCRT-III (Babst et al, 2002a; Wollert et al, 2009); and the Vps4–Vta1 complex (Babst et al, 1998). In this study, we focus on the coordination of the first two steps, which is mediated by direct binding between the ESCRT-0 and ESCRT-I complexes.

The current model of ESCRT-I recruitment to endosomes downstream of ESCRT-0 stems from insights into HIV-1 budding. HIV-1 recruits the ESCRTs to budding sites via a PTAP motif in the Gag p6 domain (Garrus et al, 2001; Martin-Serrano et al, 2001; VerPlank et al, 2001; Demirov et al, 2002a, 2002b). This PTAP motif binds directly to the UEV domain of the TSG101 (also known as VPS23) subunit of human ESCRT-I, and the structure of the complex has been solved by solution NMR (Pornillos et al, 2002) and X-ray crystallography (Im et al, 2010). A PSAP motif located within an intrinsically flexible region of the Hrs subunit of ESCRT-0 (Ren et al, 2009) serves the equivalent function in ESCRT-I recruitment in the normal MVB pathway in human cells (Bache et al, 2003; Lu et al, 2003; Pornillos et al, 2003). The yeast orthologue of Hrs is Vps27. Vps27 lacks P(S/T)AP motifs, but rather has two PSDP sequences (Bilodeau et al, 2003) and a PTVP sequence (Katzmann et al, 2003) that have been proposed to serve equivalent functions in the recruitment of ESCRT-I (Figure 1A). All three of these motifs are located C-terminal to the core region of Vps27 involved in ESCRT-0 assembly (Prag et al, 2007).

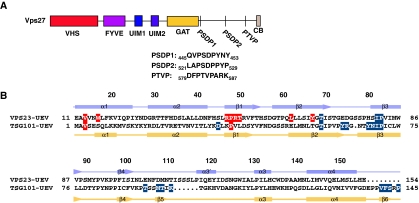

Figure 1.

Primary structures of Vps23 and Vps27 proteins. (A) Schematic representation of yeast (S. cerevisiae) Vps27. VHS (Vps27, Hrs, and STAM), FYVE (Fab 1, YOTB, Vac 1, and EEA1), UIM (ubiquitin-interacting motif), GAT domain (GGA and Tom1), and CB (clathrin-binding motif). PSDP and PTVP refer to the proposed Vps23-binding motifs. (B) The amino-acid sequences of yeast Vps23 and human TSG101-UEV domain are aligned based on the three-dimensional structural superposition. The secondary structure of Vps23-UEV (coloured in light blue) is listed above the alignment; the corresponding secondary structure of TSG101-UEV is shown under the sequence alignment. The residues involved in Vps27-PSDP1 peptide binding are highlighted in red upon Vps23-UEV domain. The residues involved in HIV-1 Gag PTAP or human Hrs-PSAP peptide binding are coloured in blue.

Despite the seeming parallels in the ESCRT-0:ESCRT-I interaction in humans and yeast, there are also important differences. The high-resolution crystal structures of P(S/T)AP peptides from HIV-1 and from the human Hrs subunit of ESCRT-0 bound to the human TSG101-UEV domain showed that the Ala residue of the motif is surrounded on every side by a shallow hydrophobic pocket. The nature of this backbone surrounding this pocket is such that it is difficult to model any simple series of amino-acid changes that would convert it to bind the Asp or Thr residues of the putative motifs in Vps27 (Im et al, 2010). Indeed, a peptide based on one of the Vps27-PSDP motifs does not bind to the human UEV domain (Im et al, 2010). Moreover, the overall binding site for the apparently conserved Pro and Ser/Thr residues of the motif is not preserved in the crystal structure of the UEV domain of Vps23 (Figure 1B), the yeast orthologue of TSG101 (Teo et al, 2004). In order to resolve these questions, we characterized the binding of peptides based on the two Vps27-PSDP motifs to the Vps23-UEV domain and determined the crystal structure of a complex with the first PSDP motif. Remarkably, the peptide binds to a basic site near the N-terminus of the UEV domain, contrary to expectation, yet consistent with the importance of the Asp residue and the lack of conservation of the P(S/T)AP-binding site in yeast Vps23.

Results

Structure of a PSDP peptide bound to Vps23-UEV

The nine-residue peptide ‘PSDP1’ comprising residues 445QVPSDPYNY453 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Vps27 (Figure 1A) was co-crystallized with the UEV domain of S. cerevisiae Vps23. The structure was determined by molecular replacement using the coordinates of the Vps23-UEV domain bound to ubiquitin (1UZX) (Teo et al, 2004) and refined at 1.85 Å resolution (Table I; Figure 2A and B). The PSDP1 peptide binds in a groove between the α1-helix and the β1–β2 strands of the UEV domain (Figures 1B and 2B). We designate this site ‘type II’ to distinguish it from the P(S/T)AP-binding region of the human TSG101-UEV domain (Figures 1B and 2C). The TSG101 site, which we designate ‘type I’, is formed by the β2 and β3 strands, part of the β4–α3 loop, and the C-terminal strand β6 (Figures 1B and 2C). The two sites are entirely distinct from one another.

Table 1. Statistics of data collection and crystallographic refinement.

| Crystal | Vps23-UEV/Vps27-PSDP1 | Apo Vps23-UEV |

| Constructs | Vps23 (1–160) Vps27-PSDP1:445 QVPSDPYNY453 | Vps23 (1–160) |

| Space group | C2221 | P212121 |

| Unit cell | a=95.20 Å, b=142.38 Å, c=32.07 Å | a=36.06 Å, b=47.14 Å, c=92.95 Å |

| X-ray source | APS 22-ID | APS 22-ID |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.85 (1.85–1.88) | 1.45 (1.48–1.45) |

| No. of unique reflections | 18 396 | 27 632 |

| I/σ (I) | 14.3 (4.9) | 22.2 (2.6) |

| Rsym (%) | 12.4 (39.0) | 11.8 (68.9) |

| Data completeness (%) | 99.8 (98.8) | 99.9 (98.9) |

| Refinement | ||

| R factor (%) | 18.3 (18.0) | 16.4 (19.9) |

| Free R factor (%) | 20.3 (23.4) | 18.4 (22.6) |

| R.m.s. bond length (Å) | 0.007 | 0.006 |

| R.m.s. bond angle (Å) | 1.113 | 1.09 |

| Average B-value (Å) | 29.0 | 13.9 |

| Number of atoms | Protein 1231; peptide 64; water 151 | Protein 1244; water 122; Zn2+ 9; Cl− 1; Imidazole 35; acetate 16 |

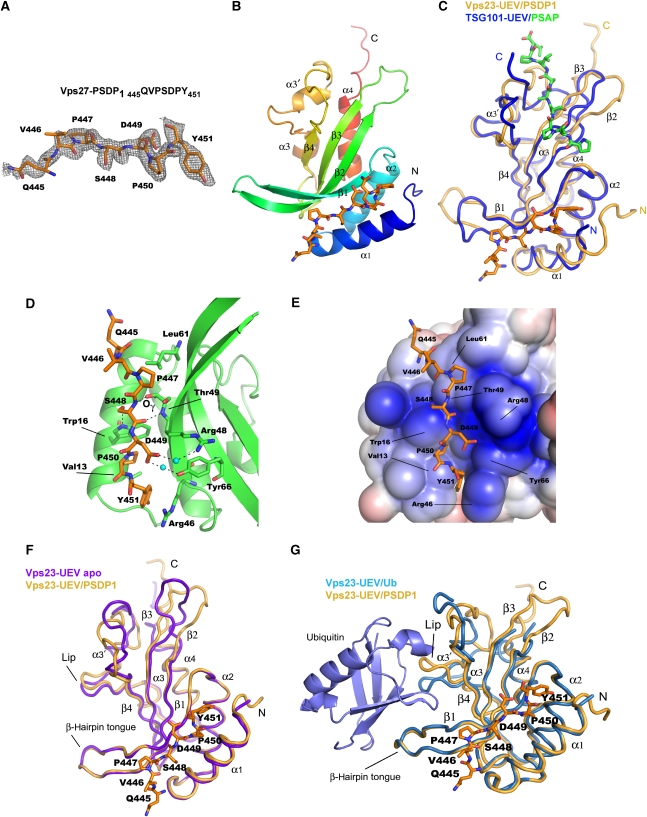

Figure 2.

Structure of the yeast Vps23-UEV domain bound to the Vps27-PSDP1 peptide. (A) Simulated-annealing Fo–Fc omit map of Vps27-PSDP1 peptide with the final model superimposed. The map is contoured at 2.0 σ. (B) Overall structure of yeast Vps23-UEV domain (coloured blue to red from the N- to C-terminus) in complex with Vps27-PSDP1 peptide (orange). (C) Structural comparison of the yeast (orange) and human (blue protein, green peptide; PDB id: 3OBQ) UEV domains bound to their cognate ESCRT-0 peptides. (D) A ball and stick representation of the Vps27-PSDP1 peptide (orange) binding to Vps23-UEV domain (green). (E) Electrostatic surface representation of the Vps23-UEV/Vps27-PSDP1 peptide. The electrostatic surface was coloured using the APBS tool within PyMOL with saturating blue and red colour corresponding to ±3 kT/e. (F) Structural comparison between the PSDP1-bound (orange) and unliganded (blue) UEV domains. (G) Structural comparison between the PSDP1-bound (orange) and ubiquitin-bound (blue; PDB id: 1UZX) UEV domains.

The residues Ser448, Asp449, and Pro450 form the most extensive interactions with the UEV domain type II site (Figure 2D). These three central residues are in a β-strand conformation. The main-chain carbonyl of Vps27 Ser448 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone amide of Vps23 Thr49, and the main-chain amide of Ser448 hydrogen bonds with the side-chain hydroxyl of Thr49. Thus, the short β strand of the peptide is slightly displaced compared with what its position would have been in a canonical β-sheet. This short central tripeptide is the locus of the most critical recognition elements.

Trp16 of Vps23 is the linchpin of the type II peptide binding site. The side-chain hydroxyl of Ser448 makes a hydrogen bond with the side-chain indole Nε of Vps23 Trp16. This interaction explains the requirement for a Ser at position –2 in the yeast Vps23-binding motif, following the numbering scheme in which the final Pro is residue 0 (Im et al, 2010). The acidic side chain of Vps27 Asp449 is located within 5–7 Å of the guanidine groups of Arg46, Arg48, and Arg50 of Vps23. The Asp449-binding site has a highly electropositive character, with the maximum electrical potential centred on the binding site for the Asp side chain (Figure 2E). No direct hydrogen bonds are formed with any of the Arg side chains, but there is a water-mediated interaction with Arg48. Furthermore, Asp449 forms another water-mediated hydrogen bond with the hydroxyl group of Vps23 Tyr66. The combination of electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions explains the preference for Asp at position –1 of the yeast Vps23-binding motif. One face of the ring of Vps27 Pro450 interacts with Val13 and Pro47 of Vps23. The other face of Pro450 packs against Vps23 Trp16. The dual interactions of Vps23 Trp16 with both the Ser and Pro of the motif highlight this residue as the central defining element of the Vps27-binding site on Vps23.

More peripherally, only one residue each N- and C-terminal to the core of the motif interact with the UEV domain. Pro447 interacts via one face with Vps23 Val51 and Leu61, while its other face is exposed to solvent. Thus, the first Pro –3 of the motif seems less central to recognition than the final Pro 0. Position +1 of the motif is not conserved, even within Vps27. Nevertheless, the side chain of Tyr451 at the +1 position stacks against the flat guanidino group of Vps23 Arg46, and makes van der Waals contact with Val13. At this stage, the next residue of the PSDP1 peptide is the polar Asn452. Here, the peptide turns toward solvent and is poorly visualized in electron density. While less central in their roles, the residues that immediate flank the central PSDP sequence still modulate binding, as described below.

Structure of the unliganded Vps23-UEV domain and conformational changes

In order to determine whether PSDP motif binding to the type II site on the UEV domain induces structural changes, the structure of the unliganded Vps23-UEV domain was determined and refined at 1.45 Å resolution (Supplementary Figure S1). The unliganded domain was crystallized in a different space group and with different solvent than the peptide complex. Overall, the structures differ by 1.5 Å r.m.s.d. over 128 Cα positions. The largest changes are in the β2–β3 hairpin, helix α3′, the ubiquitin-binding ‘lip’ region (the loop between α3′ and α3), and the C-terminus (Figure 2F). The backbone coordinates in the PSDP-binding region are almost identically superimposable in the PSDP1 bound and unliganded structures. Even the UEV domain side chains directly involved in peptide binding barely change position. The largest side-chain shift is a 5-Å movement of the guanidine group of Arg46, which allows it to pack against Tyr451 of the peptide. Therefore, we conclude that the structure differences in the C-terminal half of the domain are caused by differences in the crystal conditions and packing, and are not caused by PSDP1 motif binding.

A three-way comparison of the ubiquitin-bound, peptide-bound, and unbound states reinforces these impressions. The side-chain conformations in the PSDP-binding site in virtually unchanged between all three of the structures. This is a remarkable display of rigidity in three different structures determined in different space groups and bound to different ligands. The backbone of the β1–β2 hairpin, which connects the PSDP and ubiquitin binding sites, is nearly superimposable in all three. The largest difference in the β1–β2 hairpin is a change in the rotamer of the Ser55 side chain in the ubiquitin complex so as to bind ubiquitin. Thus, PSDP peptide binding appears not to produce any significant conformational change in the Vps23-UEV domain and there appears to be no allosteric communication between these two sites. Ubiquitin binding does trigger substantial conformational changes in the same regions that vary in structure between the unbound and peptide-bound complexes due to crystal packing. Thus, induced fit upon ubiquitin binding takes advantage of the intrinsic flexibility of the relevant interaction loops in the UEV domain.

Comparison of type I and II P(S/T)XP-binding sites

The hairpin turn connecting the β1 and β2 strands is involved in ubiquitin binding in both yeast (Teo et al, 2004) and human UEV domains (Sundquist et al, 2004). However, the ubiquitin-binding site does not overlap with the PSDP-binding site (Figure 2G). The crystal structures of the peptide-bound yeast and human UEV domains are superimposable over most of their N-terminal and central portions, with 118 Cα positions deviating by 1.3 Å. The backbone C-terminal to β4, which includes several key type I PTAP-binding residues, follows a different course in the Vps23-UEV domain. Following the C-terminus of helix α4 in the yeast structure, the backbones of the non-conserved C-terminal regions diverge in different directions. The C-terminal extension of the human UEV domain folds into strand β6 in the PTAP-bound complex and is central to the architecture of the type I site. The only part of the type I site where the backbone conformation is preserved from yeast to humans is in strand β3. Yet even here, equivalent Cα positions differ by ∼3 Å, and most of the key type I site residues are not conserved. The type II site present a very different picture in that the backbone conformation in the yeast and human UEV domains is nearly identical. This N-terminal zone appears to be far more structurally rigid than the regions surrounding the ubiquitin and type I binding sites. Here, key PSDP-binding residues in Vps23, notably Trp16, Arg48 and Arg50, are not conserved in TSG101. The inability of TSG101 to bind PSDP motifs derives not from gross structural changes, but rather from deficits in a handful of critical type II interactions.

Isothermal titration calorimetry of motif binding to the UEV domain

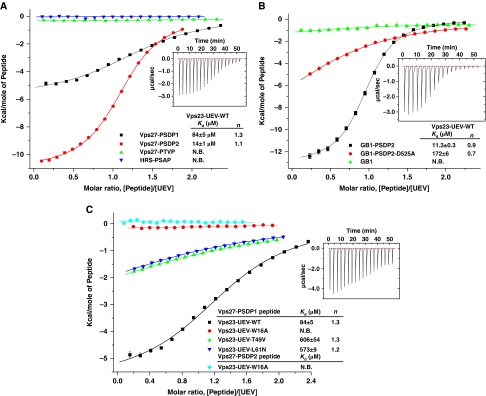

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) analysis showed that both of the PSDP motif peptides bound with tens of micromolar affinity to the UEV domain (Figure 3A). The PSDP1 peptide binds with Kd=84 μM, compared with Kd=14 μM for the PSDP2 peptide. The peptides bind with a best-fit stoichiometry of n=1.1 to 1.3, which we interpret to signify single site binding. The differences in affinity between the PSDP1 and PSDP2 peptides show that flanking residues outside the core motif do modulate affinity to some extent. The PTVP did not bind to the UEV domain, however, nor did the Hrs-PSAP peptide. The absence of PTVP binding is consistent with an essential role for the (−1) position as a specificity determinant. Indeed, the D525A mutant of the PSDP2 peptide had a 16-fold lower affinity than wild type (Figure 3B). The lack of high affinity PSAP binding is consistent with the gross changes in the C-terminal part of the yeast UEV structure relative to human, which obliterate most of the type I site. We therefore interpret the weak binding of the D525A mutant peptide as a residual type II interaction, not a type I interaction. The W16A-UEV mutant completely fails to bind PSDP peptides, consistent with the central role of Trp16 (Figure 3C). The mutant T49V, designed to eliminate the hydrogen bond with the amide nitrogen of the –2 residue, reduced, but did not completely abolish binding. Similarly, the L61N mutant, designed to disrupt the hydrophobic contact between the Pro(–3) ring and Leu61, impaired binding. These results corroborate the identification of the two PSDP motifs as the loci of Vps27 binding to Vps23. They also confirm that the crystallographic results and solution binding data refer to the same underlying interaction.

Figure 3.

Isothermal titration calorimetry of UEV–peptide interactions. (A) Binding of various P(S/T)XP peptides to wild-type Vps23-UEV domain. The inset showed the differential heat released when Vps27-PSDP2 peptide (0.3 mM) was injected into the Vps23-UEV wild-type solution (3 mM) in 2.1 μl aliquots (Hrs-PSAP peptide sequence—PTPSAPVPL). (B) Binding of wild-type and mutant Vps27-PSDP2 peptides fused to the carrier protein GB1 to Vps23-UEV. (C) Binding of Vps27-PSDP peptides to Vps23-UEV wild type or mutants. The insets show the differential heat released in each experiment. Error bars represent the s.d. of three measurements.

Cellular function of the Vps23 type II site

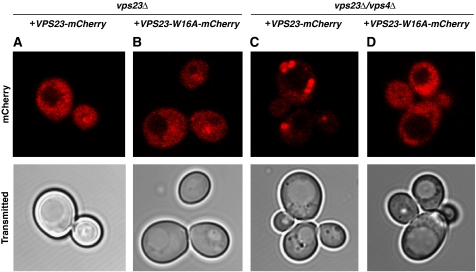

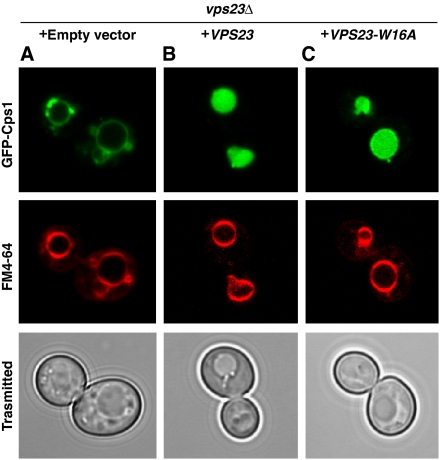

ESCRT-I is predominantly cytosolic in both wild-type and the type II site mutant VPS23W16A (Figure 4A and B). Wild-type ESCRT-I becomes partially trapped in the class E compartments that are induced in vps4Δ cells (Katzmann et al, 2001) (Figure 4C), which provides a convenient diagnostic for the determinants of endosomal localization. The mean number of wild-type Vps23-containing puncta was 1.4 per cell based on blind counting. VPS23W16A (Figure 4D), but not VPS23, was cytosolic in vps4Δ vps23Δcells, indicating an impairment of endosomal localization in the VPS23W16A form of ESCRT-I. The mean number of Vps23W16A-containing puncta was reduced to 0.2 per cell. This pattern is similar to the cytosolic distribution of Vps23-GFP seen previously in vps27Δ524-622vps4Δ cells (Katzmann et al, 2003), where the Vps27 deletion eliminated the second PSDP motif. We next examined the effect of blocking the PSDP-binding site on trafficking of the canonical ESCRT cargo, Cps1. Cps1 sorting to the vacuole is normal in vps23ΔVPS23 and vps23ΔVPS23W16A (Figure 5B and C). The observation of a normal Cps1 sorting phenotype in vps23ΔVPS23W16A cells mirrors the finding that a double PSDP mutant allele of VPS27 sorts Ste3 and the artificial MVB cargo Fth1-Ub normally, and is not strikingly divergent from the mild Cps1 sorting defect in these cells (Bilodeau et al, 2003).

Figure 4.

Localization of wild-type and mutant Vps23. Fluorescence microscopy of vps23Δ (A, B) and vps23Δvps4Δ (C, D) cells expressing VPS23-mCherry (A, C) or VPS23-W16A-mCherry (B, D) demonstrates that the W16A mutation nearly eliminates the enrichment of Vps23 at class E compartments. For quantification of mCherry-labelled puncta in vps23Δvps4Δ cells, 40 fields (20 each for wild type and W16A) containing an average of 14 cells/field were imaged, the images were coded with random identifiers, and puncta were counted blind to genotypic identity.

Figure 5.

The Vps27-binding site on Vps23 is non-essential for Cps1 sorting. The vps23Δ cells were co-transformed with the empty vector (A), GFP-CPS1 and VPS23 (B), or VPS23-W16A (C) to assess the MVB sorting. The VPS23-W16A mutant showed the normal Cps1 sorting.

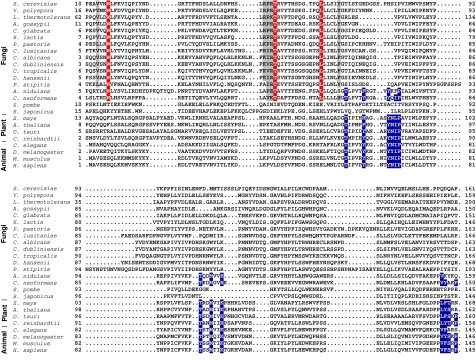

Evolution of type I and type II binding sites

Trp16, Thr49, and Leu61 of S. cerevisiae Vps23 can be considered diagnostic residues for the type II site. These residues are identically conserved in all fungi examined, with the exception of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces (Figure 6). This trio is absent from essentially all of the Vps23 orthologues in fission yeast, plants, and animals, however. On the other hand, key residues of the type I site, such as Met95 of human TSG101, are conserved in all multicellular organisms examined, but absent in most fungi. Aspergillus nidulans and Cryptococcus neoformans are interesting exceptions in that their Vps23 sequences contain both types of binding site.

Figure 6.

Conservation of type I and type II P(S/T)XP-binding sites. The signature of the type II site is a Trp residue in the first α-helix, which is conserved in most fungi, except fission yeasts. The conserved residues in the type II binding site are highlighted in red; key type I binding site residues are coloured in blue.

Discussion

This study was conceived in the wake of structural analysis of the human ESCRT-0 and HIV-1 P(S/T)AP motifs bound to the UEV domain of human VPS23 at increasing levels of resolution (Pornillos et al, 2003; Im et al, 2010). The detailed picture of the human P(S/T)AP:UEV interaction showed that Ala(–1) of the motif was tightly packed in a shallow pocket that left no room for the substitution of even a single non-hydrogen atom for one of the methyl hydrogens of the side chain. It was thus difficult to reconcile with the presence of a putative Asp or Thr residue replacing the Ala(–1) of the human motif with a common binding mode. The low sequence and structural conservation between the type I region in the yeast and human UEV domains was another concern. Here, we found that the PSDP motifs are the bona fide Vps23-binding site on Vps27. We have answered the puzzle posed at the outset by showing that the yeast PSDP motifs bind to a completely novel site on the yeast UEV domain.

We have also shown that P(S/T)AP and PTVP-type sequences do not bind strongly to the yeast Vps23-UEV domain, which constrains the number and identity of its binding partners. The improved understanding of the determinants for interaction with the yeast UEV domains should be useful in identifying (and ruling out) potential binding partners in various species. Our observations are consistent, for example, with the recent identification of the yeast arrestin-related protein Rim8 as an SDP-containing Vps23 interactor (Herrador et al, 2010).

The observation that VPS23W16A prevents enrichment of ESCRT-I in class E compartments vps4Δ cells confirms the physiological relevance of the novel type II PSDP-binding site on the Vps23-UEV domain. It might seem counterintuitive that expression of this same VPS23W16A allele does not lead to a Cps1 sorting defect. Enrichment of ESCRTs in class E compartments induced in strains such as vps4Δ is an imperfect surrogate for the normal process of transient recruitment and function of ESCRTs at endosomes. Indeed, the dissociation of ESCRT-0, -I, and -II from endosomes is not strictly dependent on Vps4 (Nickerson et al, 2010). In vitro functional analysis of the ESCRT-0:ESCRT-I interaction showed that PSDP mutant of ESCRT-0 microdomains had reduced, but still non-zero co-localization with ESCRT-I and -II-induced buds on giant unilamellar vesicles (Wollert and Hurley, 2010). The yeast findings mirror those in human cells. In HeLa cells, a human TSG101 allele defective in its P(S/T)AP-binding site is still able to rescue endogenous EGF receptor sorting following knockdown of endogenous TSG101 (Im et al, 2010). Taken together, these findings reinforce the concept that cargo sorting is robust to disruptions of the ESCRT-0:ESCRT-I interaction across species from yeast to humans.

It is remarkable that two very similar motifs in two orthologous proteins, which bind to the same conserved domain in their orthologous binding partners, use completely different binding sites and modes of recognition. How might this have arisen in evolution? A few fungi, such as Aspergillus, have Vps23 proteins that contain both type I and II sites (Figure 6). PSDP and P(S/T)AP motifs are often found within larger tracts of Pro- and Ser-rich sequence, which tend to be compositionally simple and degenerate. In the overlaid structures of the peptide-bound yeast and human UEV domains, the C-terminus of the yeast peptide is 17 Å from the N-terminus of the human peptide, with no intervening obstacles. It seems conceivable that the proteome of an ancestor of Aspergillus or a related species might include a protein containing a PSDP-like sequence followed by a short linker and then a P(S/T)AP-like sequence, although we have not been able to firmly establish such a ‘missing link’ Vps27 orthologue.

It is striking that plant Vps23-UEV domains all appear to have an intact type I binding site, even though plants lack Vps27 orthologues (Leung et al, 2008). Plants and Dictyostelium contain Tom1 proteins that bind ubiquitin and have been proposed to substitute for ESCRT-0 in these organisms (Blanc et al, 2009). At least some Tom1-like proteins, including human Tom1L1 and Dictyostelium DdTom1, bind to ESCRT-I via P(S/T)AP motifs (Puertollano, 2005; Blanc et al, 2009). This is consistent with the preservation of the type I binding site in the ESCRT-I UEV domain of Dictyostelium and other species whose proteomes contain Tom1-like proteins but not ESCRT-0. The conceptual division of ESCRT-I complexes into type I and type II motif binders illuminates the complexities of ESCRT evolution. Moreover, these results show how an orthologous interacting motif/domain pair can co-evolve to use strikingly different structural binding modes across the eukarya.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

DNA coding for the S. cerevisiae Vps23-UEV domain (residues 1–160) was subcloned into the pGST2 vector (Sheffield et al, 1999). The mutation C133A was engineered in order to improve the crystallization properties of Vps23-UEV. This C133A mutant is referred as wild-type UEV in the rest of this study. The C133A background was used for all structural and in vitro experiments, but the true wild type was used for in vivo studies. All other UEV mutants for use in in vitro experiments were prepared in the C133A background. Site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) was confirmed by DNA sequencing. All Vps23-UEV proteins were tagged with an N-terminal GST followed by a TEV protease cleavage site. The plasmids coding for Vps23-UEV wild type or mutants were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells and overexpressed in ZYM-5052 autoinduction medium (Studier, 2005). Cell pellets were resuspended in 1 × PBS buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and lysed by sonication. The GST-Vps23-UEV was purified using a glutathione-sepharose column (GE Healthcare) and then eluted in 20 mM L-glutathione reduced/1 × PBS buffer. After TEV cleavage overnight at 4°C, the samples were passed through glutathione-sepharose and then Ni resin to remove GST tag and TEV protease. The flow through solution was concentrated and applied to a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare) in 20 mM Tris pH 7.3, 100 mM NaCl.

The yeast Vps27 residues 521–528 (PSDP2) and the corresponding D525A mutant were subcloned into a pHis2 vector (Sheffield et al, 1999) derivative, which contains an N-terminal His6 tag, followed by GB1-T2Q (immunoglobulin G binding domain B1 of streptococcal protein G, T2Q mutant) and a linker encoding the residues DTTENLYFQGAMGSGIQR. GB1 fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells in Terrific Broth medium, and induced overnight at 20°C. Cells were lysed by sonication under denaturing condition: 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 6 M urea. The cleared cell lysate was loaded onto a Ni-NTA affinity column (Qiagen), and urea concentration in the wash buffer was gradually decreased to refold the protein on the column. The proteins were eluted in 0.2 M imidazole. The elution samples were diluted five-fold with monoQ buffer (30 mM HEPES, pH 7.10), then purified on a monoQ 5/50GL column (GE Healthcare). The pure fractions were concentrated and applied onto a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 column in the ITC buffer. The mass of each GB1 fused protein was confirmed by electrospray mass spectrometry.

Crystallization and crystallographic analysis

The three Vps27 peptides used in this study, denoted PSDP1, PSDP2 and PTVP, were synthesized and purified on HPLC by New England Peptide (Gardner, MA). For crystallization, PSDP1 peptide and Vps23-UEV domain were mixed at a 3:1 molar ratio. Crystals of the complex were obtained at 1 mM protein concentration and equilibrated against 0.2 M sodium dihydrogen phosphate, 20% PEG 3350 at 15°C. Crystals were cryoprotected in reservoir solution supplemented with 20% glycerol and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Crystals of apo Vps23-UEV domain were grown over a reservoir of 0.2 M zinc acetate, 0.1 M imidazole pH 8.0, 25% 1,2-propanediol, 10% glycerol at 15°C. Apo UEV crystals were harvested in cryoloops directly from the crystal drop and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Native data were collected from a single frozen crystal using a MAR CCD detector at beamline 22-ID, Advanced Photon Source. All data were processed and scaled using HKL2000. A molecular replacement solution for the unliganded UEV domain was found using Vps23-UEV structure (PDB: 1UZX) as a search model with Phaser (McCoy et al, 2007). Multiple Zn, acetate, and imidazole molecules from the crystallization medium were detected and included in the refined structure. The unliganded UEV structure was then used as a search model to solve the structure of the PSDP1 complexed form. Model building and refinement was using Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004), Phenix (Adams et al, 2010), and AutoBuster (Blanc et al, 2004) (Table I). Structural figures were generated by PyMol (W Delano; http://pymol.sourceforge.net/).

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Purified wild-type and mutant Vps23-UEV domains were dialysed against ITC buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.20, 150 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol) at 4°C overnight. Each peptide was dissolved in water to make a stock solution (40 mM). Further dilution in the ITC buffer was adjusted using 2 × ITC buffer before the ITC experiment. The sample cell contained 0.2 ml of 0.27–0.6 mM UEV domain and the peptides or GB1–peptide fusions (3 or 6 mM) were added in 18 injections of 2.1 μl each. Data from peptide injections into buffer blanks were subtracted from sample data before analysis. Measurements were carried out on an itc200 instrument (MicroCal). The data were processed using Origin software (MicroCal). The binding constant (Kd) was fitted using a one-site model, which yielded excellent data fits.

Plasmid construction and yeast strains

The yeast strain vps23Δ::KanR (BY4741) was obtained from Open Biosystems. The vps23Δvps4Δ strain (MCY18) was a kind gift of Markus Babst (Curtiss et al, 2006). The complete expression cassette of VPS23 was amplified from yeast genomic DNA (Novagen) and cloned into HindIII/EcoRI-digested YCplac111 vector. The whole cassette coding for Vps23 tagged with a C-terminal linker (GGGGSGGGGS) followed by the coding sequence for mCherry was inserted into the HindIII and EcoRI sites of the YCplac111 single-copy vector. VPS23-W16A-mCherry and the VPS23-W16A mutants were generated by site-directed Quick-change mutagenesis. Plasmids containing VPS23 wild type or mutants and GFP-CPS1 (Odorizzi et al, 1998) were co-transformed into vps23Δ for the Cps1 cargo sorting assay. The VPS23-mCherry wild type or mutant was transformed into vps23vps4Δ strain for localization experiments.

Confocal fluorescence microscopy

Yeast strains expressing the appropriate alleles were harvested at an optical density A600 of 0.3–0.5 and labelled with FM4-64 for vacuolar membrane staining (Vida and Emr, 1995). Uptake of FM4-64 by live cells was performed at 30°C for 1 h, after which cells were resuspended in selection media and incubated for 30 min at 30°C. Cells were imaged with a × 100 oil-immersion objective on a LSM780 scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging). Results presented were based on at least three replicate experiments with observations of >100 cells each.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Markus Babst and Will Prinz for strains, and Rob Piper for discussions. Data were collected at Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team 22-ID beamline at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38. This research was supported by the Intramural Program of the NIH, NIDDK (JHH), the Intramural AIDS Targeted Anti-viral Program of the Office of the Director, NIH (JHH), and an Intramural AIDS Research Fellowship (XF).

Author contributions: XR and JH conceived and designed the study; XR carried out all the experiments; XR and JH analysed the data; and JH wrote the manuscript with substantial input from XR. Crystallographic coordinates for the PSDP1-bound and unliganded UEV domain structures have been deposited in the RCSB data bank with accession codes 3R42 and 3R3Q.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr Sect D 66: 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst M, Katzmann DJ, Estepa-Sabal EJ, Meerloo T, Emr SD (2002a) ESCRT-III: an endosome-associated heterooligomeric protein complex required for MVB sorting. Dev Cell 3: 271–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst M, Katzmann DJ, Snyder WB, Wendland B, Emr SD (2002b) Endosome-associated complex, ESCRT-II, recruits transport machinery for protein sorting at the multivesicular body. Dev Cell 3: 283–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst M, Wendland B, Estepa EJ, Emr SD (1998) The Vps4p AAA ATPase regulates membrane association of a Vps protein complex required for normal endosome function. EMBO J 17: 2982–2993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bache KG, Brech A, Mehlum A, Stenmark H (2003) Hrs regulates multivesicular body formation via ESCRT recruitment to endosomes. J Cell Biol 162: 435–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilodeau PS, Winistorfer SC, Kearney WR, Robertson AD, Piper RC (2003) Vps27-Hse1 and ESCRT-I complexes cooperate to increase efficiency of sorting ubiquitinated proteins at the endosome. J Cell Biol 163: 237–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc C, Charette SJ, Mattei S, Aubry L, Smith EW, Cosson P, Letourneur F (2009) Dictyostelium Tom1 participates to an ancestral ESCRT-0 complex. Traffic 10: 161–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc E, Roversi P, Vonrhein C, Flensburg C, Lea SM, Bricogne G (2004) Refinement of severely incomplete structures with maximum likelihood in BUSTER-TNT. Acta Crystallogr Sect D 60: 2210–2221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coonrod EM, Stevens TH (2010) The yeast vps class E mutants: the beginning of the molecular genetic analysis of multivesicular body biogenesis. Mol Biol Cell 21: 4057–4060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtiss M, Jones C, Babst M (2006) Efficient cargo sorting by ESCRT-I and the subsequent release of ESCRT-I from multivesicular bodies requires the subunit Mvb12. Mol Biol Cell 18: 636–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirov DG, Ono A, Orenstein JM, Freed EO (2002a) Overexpression of the N-terminal domain of TSG101 inhibits HIV-1 budding by blocking late domain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 955–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirov DG, Orenstein JM, Freed EO (2002b) The late domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 p6 promotes virus release in a cell type-dependent manner. J Virol 76: 105–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr Sect D 60: 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrus JE, von Schwedler UK, Pornillos OW, Morham SG, Zavitz KH, Wang HE, Wettstein DA, Stray KM, Cote M, Rich RL, Myszka DG, Sundquist WI (2001) Tsg101 and the vacuolar protein sorting pathway are essential for HIV-1 budding. Cell 107: 55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrador A, Herranz S, Lara D, Vincent O (2010) Recruitment of the ESCRT machinery to a putative seven-transmembrane-domain receptor is mediated by an arrestin-related protein. Mol Cell Biol 30: 897–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley JH, Hanson PI (2010) Membrane budding and scission by the ESCRT complexes: it's all in the neck. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 556–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im YJ, Kuo L, Ren X, Burgos PV, Zhao XZ, Lui F, Burke TR, Bonifacino JS, Freed EO, Hurley JH (2010) Crystallographic and functional analysis of the ESCRT-1/HIV-1 Gag PTAP interaction. Structure 18: 1536–1547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann DJ, Babst M, Emr SD (2001) Ubiquitin-dependent sorting into the multivesicular body pathway requires the function of a conserved endosomal protein sorting complex, ESCRT-I. Cell 106: 145–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann DJ, Stefan CJ, Babst M, Emr SD (2003) Vps27 recruits ESCRT machinery to endosomes during MVB sorting. J Cell Biol 162: 413–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung KF, Dacks JB, Field MC (2008) Evolution of the multivesicular body ESCRT machinery; retention across the eukaryotic lineage. Traffic 9: 1698–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Hope LWQ, Brasch M, Reinhard C, Cohen SN (2003) TSG101 interaction with HRS mediates endosomal trafficking and receptor down-regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 7626–7631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Serrano J, Zang T, Bieniasz PD (2001) HIV-I and Ebola virus encode small peptide motifs that recruit Tsg101 to sites of particle assembly to facilitate egress. Nat Med 7: 1313–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr 40: 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald B, Martin-Serrano J (2009) No strings attached: the ESCRT machinery in viral budding and cytokinesis. J Cell Sci 122: 2167–2177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita E, Sundquist WI (2004) Retrovirus budding. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 20: 395–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson DP, West M, Henry R, Odorizzi G (2010) Regulators of Vps4 activity at endosomes differentially influence the size and rate of formation of intralumenal vesicles. Mol Biol Cell 21: 1023–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odorizzi G, Babst M, Emr SD (1998) Fab1p PtdIns(3)P 5-kinase function essential for protein sorting in the multivesicular body. Cell 95: 847–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper RC, Cooper AA, Yang H, Stevens TH (1995) Vps27 controls vacuolar and endocytic traffic through a prevacuolar compartment in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 131: 603–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper RC, Luzio JP (2007) Ubiquitin-dependent sorting of integral membrane proteins for degradation in lysosomes. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19: 459–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pornillos O, Alam SL, Davis DR, Sundquist WI (2002) Structure of the Tsg101 UEV domain in complex with the PTAP motif of the HIV-1 p6 protein. Nat Struct Biol 9: 812–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pornillos O, Higginson DS, Stray KM, Fisher RD, Garrus JE, Payne M, He GP, Wang HE, Morham SG, Sundquist WI (2003) HIV Gag mimics the Tsg101-recruiting activity of the human Hrs protein. J Cell Biol 162: 425–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prag G, Watson H, Kim YC, Beach BM, Ghirlando R, Hummer G, Bonifacino JS, Hurley JH (2007) The Vps27/Hse1 complex is a GAT domain-based scaffold for ubiquitin-dependent sorting. Dev Cell 12: 973–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puertollano R (2005) Interactions of Tom1L1 with the multivesicular body sorting machinery. J Biol Chem 280: 9258–9264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiborg C, Stenmark H (2009) The ESCRT machinery in endosomal sorting of ubiquitylated membrane proteins. Nature 458: 445–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X, Kloer DP, Kim YC, Ghirlando R, Saidi LF, Hummer G, Hurley JH (2009) Hybrid structural model of the complete human ESCRT-0 complex. Structure 17: 406–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield P, Garrard S, Derewenda Z (1999) Overcoming expression and purification problems of RhoGDI using a family of ‘parallel’ expression vectors. Protein Expression Purif 15: 34–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier FW (2005) Protein production by auto-induction in high-density shaking cultures. Protein Expression Purif 41: 207–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundquist WI, Schubert HL, Kelly BN, Hill GC, Holton JM, Hill CP (2004) Ubiquitin recognition by the human TSG101 protein. Mol Cell 13: 783–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo H, Veprintsev DB, Williams RL (2004) Structural insights into endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT-I) recognition of ubiquitinated proteins. J Biol Chem 279: 28689–28696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VerPlank L, Bouamr F, LaGrassa TJ, Agresta B, Kikonyogo A, Leis J, Carter CA (2001) Tsg101, a homologue of ubiquitin-conjugating (E2) enzymes, binds the L domain in HIV type 1 Pr55(Gag). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 7724–7729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vida TA, Emr SD (1995) A new vital stain for visualizing vacuolar membrane Dynamics and endocytosis in yeast. J Cell Biol 128: 779–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollert T, Hurley JH (2010) Molecular mechanism of multivesicular body biogenesis by ESCRT complexes. Nature 464: 864–873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollert T, Wunder C, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Hurley JH (2009) Membrane scission by the ESCRT-III complex. Nature 458: 172–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.