Abstract

Background and aims

Adherence to HCV therapy impacts sustained virological response (SVR), but there are limited data on adherence, particularly among injecting drug users (IDUs). We assessed 80/80 adherence (≥80% of PEG-IFN doses, ≥80% treatment), on-treatment adherence and treatment completion in a study of treatment of recent HCV infection (ATAHC).

Methods

Participants with HCV received pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) alfa-2a (180 μg/week, n=74); those with HCV/HIV received PEG-IFN alfa-2a with ribavirin (n=35). Everyone received 24 weeks of therapy. Logistic regression analyses were used to identify predictors of PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence.

Results

Of 163, 109 received treatment (HCV, n=74; HCV/HIV, n=35), with 75% ever reporting IDU. The proportion with 80/80 PEG-IFN adherence was 82% (n=89). During treatment, 14% missed ≥1 dose (on-treatment adherence=99%). Completion of 0-4, 5-19, 20-23 and all 24 weeks of PEG-IFN therapy occurred in 10% (n=11), 14% (n=15), 6% (n=7) and 70% (n=76), respectively. Participants with no tertiary education were less likely to have 80/80 PEG-IFN adherence (AOR 0.29,P=0.045). IDU prior to or during treatment did not impact 80/80 PEG-IFN adherence. SVR was higher among those with ≥80/80 PEG-IFN adherence (67% vs. 35%,P=0.007), but similar among those with and without missed doses during therapy (73% vs. 60%,P=0.309). SVR in those discontinuing therapy between 0-4, 5-19, 20-23 and 24 weeks was 9%, 33%, 43% and 76%, respectively (P<0.001).

Conclusion

High adherence to treatment for recent HCV was observed, irrespective of IDU prior to, or during, therapy. Sub-optimal PEG-IFN exposure was mainly driven by early treatment discontinuation rather than missed doses during therapy.

Keywords: injection drug users, HIV infection, discontinuation, pegylated interferon, therapy

INTRODUCTION

Pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) and ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is effective in 54-56% and 27-40% of patients with HCV [1-3] and HCV/HIV, respectively [4-5]. Sustained virological response (SVR) is associated with younger age [1-2], HCV genotype [1-3], HCV RNA [1, 3], HCV viral kinetics [6-7], fibrosis [1] and host genetics (e.g. IL28B) [8-10]. Adherence to therapy is also important and enhances SVR [11-14]. However, studies of adherence are limited by the restricted populations, small sample sizes and varying adherence definitions [14].

Treatment response is also higher among patients with recent HCV. Response rates range from 57-88% among HCV patients receiving 12-24 weeks of therapy with PEG-IFN monotherapy [15-22] and from 59-74% among HCV/HIV patients receiving 12-24 weeks of therapy with PEG-IFN and ribavirin [22-24]. In the Australian Trial in Acute Hepatitis C (ATAHC), SVR rates of 55% and 74% for HCV (PEG-IFN) and HCV/HIV participants (PEG-IFN/ribavirin) were observed after 24 weeks of therapy, respectively [22]. Among HCV participants, SVR was higher among those adherent to PEG-IFN (63% vs. 29%, P=0.025) [22]. Among those ever having injected drugs (n=63), SVR was similar for those participants who did and did not inject during treatment (59% vs. 53%, P=0.76) and was not related to injecting frequency [22].

Among healthcare providers, there are still concerns about the suitability of HCV treatment in IDUs, due to patient motivation and adherence, psychosocial issues, medical and psychiatric comorbidities, re-infection risk and the lack of infrastructure to ensure access to care [25]. However, response rates among IDUs are comparable to non-IDUs [26]. But, little is known about adherence to HCV therapy and associated factors, particularly among IDUs and those with recently acquired HCV.

The ATAHC study was designed specifically to investigate treatment for recent HCV, predominantly in those with IDU-acquired infection. The study uniquely recruited both HCV and HCV/HIV participants under the same protocol. Here, we report on the adherence to PEG-IFN and predictors of adherence in this study.

Methods

Study design

ATAHC was a multicenter, prospective cohort study of the natural history and treatment of recent HCV infection, as previously described [22]. Recruitment of HIV infected and uninfected participants was from June 2004 through November 2007 through an Australian network of tertiary hospitals (n=13) and general practice/primary care clinics (n=3). The top five sites in Sydney (n=2), Melbourne (n=2) and Adelaide (n=1) recruited 84% of participants. Recent infection with either acute or early chronic HCV infection with the following eligibility criteria: First positive anti-HCV antibody within 6 months of enrolment; and either

Acute clinical hepatitis C infection, defined as symptomatic seroconversion illness or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level greater than 10 times the upper limit of normal (>400 IU/L) with exclusion of other causes of acute hepatitis, at most 12 months before the initial positive anti-HCV antibody; or

Asymptomatic hepatitis C infection with seroconversion, defined by a negative anti-HCV antibody in the two years prior to the initial positive anti-HCV antibody.

All participants with HCV RNA during the screening period (maximum 12 weeks) were assessed for HCV treatment eligibility. Heavy alcohol intake and active drug use were not exclusion criteria. From screening, participants were followed for up to 12 weeks to allow for spontaneous HCV clearance and if HCV RNA remained detectable were offered treatment. Participants were then seen at baseline and 12 weekly intervals for up to 144 weeks (individuals receiving HCV treatment were also seen at 4-weekly intervals up to week 12).

All study participants provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (primary study committee) as well as through local ethics committees at all study sites. The study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov registry (NCT00192569).

HCV treatment

Participants who began HCV treatment received pegylated interferon-α2a (PEG-IFN) 180 micrograms weekly for 24 weeks. Due to non-response at week 12 in the initial two participants with HCV/HIV co-infection, the study protocol was amended to provide PEG-IFN and ribavirin combination therapy for 24 weeks in HIV positive individuals. Ribavirin was prescribed at a dose of 1000-1200 mg for those with genotype 1 infection and 800 mg in those with genotype 2/3. HCV treatment was self-administered (with the exception of the first dose which was supervised by study personnel). Treatment sites were offered the option of administering or supervising injections, if this was felt necessary to optimize adherence for individual patients. Prior to treatment, medical staff informed patients on the recommended methods of medication storage, self-injection, and management and disposal of needles and syringes.

Study assessments

A questionnaire was administered at screening and every 12 weeks, to obtain information on injection of illicit drugs, social functioning (Opiate Treatment Index Social Functioning Scale) [27] and psychological parameters [Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) [28] and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) [29]].

Study visits occurred every two weeks from baseline to week 8 and every four weeks from week 8 until the end of treatment. All participants had the same number of study visits, irrespective of injecting drug use history. At each study visit, weekly adherence to PEG-IFN was recorded by the research nurse on a standardized case report form which included the method of dose administration, whether the full dose, adjusted dose or no dose of PEG-IFN was administered, as well as reasons for dose adjustment.

Study definitions

PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence

Defined as the receipt of ≥80% of scheduled PEG-IFN doses for ≥80% of the scheduled treatment period. For participants in whom therapy was terminated at 12 weeks due to virological non-response, the scheduled treatment period was defined as 12 weeks.

On-treatment PEG-IFN adherence

Calculated by subtracting the number of missed PEG-IFN doses from the total duration of treatment (week that treatment was discontinued or completed) and dividing by the total therapy duration. This measures the proportion of PEG-IFN doses received from the time that treatment was initiated until treatment was discontinued or completed.

PEG-IFN dose-modification

A reduction in the dose of PEG-IFN at any time during treatment.

Early PEG-IFN treatment discontinuation

Discontinuation of PEG-IFN prior to the per-protocol planned end of treatment (24 weeks). This includes participants with clinician-directed discontinuation for virological non-response.

Study outcomes

The main study outcome was to assess PEG-IFN adherence (given that only HCV/HIV participants received ribavirin). Evaluation of HCV treatment response was based on intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses that included all participants who received at least one injection of PEG-IFN therapy. The primary endpoint for treatment was the proportion of participants with undetectable qualitative HCV RNA rates at week 48 (SVR).

Statistical analyses

We hypothesized that non-adherence to PEG-IFN therapy during recent HCV infection was due to early PEG-IFN treatment discontinuation, rather than missed doses of PEG-IFN. Weekly PEG-IFN adherence, PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence, on-treatment PEG-IFN adherence, missed PEG-IFN doses during treatment, PEG-IFN dose-modifications and early treatment discontinuations were assessed. Bi-variate comparisons of characteristics of participants across different measures of adherence were tested using the chi-squared test. Time to treatment discontinuation was evaluated using Kaplan Meier analysis. Lastly, the impact of on-treatment PEG-IFN adherence and early PEG-IFN discontinuation on SVR were also evaluated.

Logistic regression analyses were used to estimate crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) to identify predictors of PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence and HCV treatment completion. In unadjusted analyses, potential predictors were determined a priori and included sex, age, education, accommodation, employment, methadone/buprenorphine treatment, social functioning, current depression, IDU at baseline (ever, past 6 months and past 30 days), alcohol, HIV infection, estimated duration of HCV and acute presentation (acute clinical, asymptomatic). Accommodation was categorized according to rented housing, privately owned housing or unstable housing (this included hostels, drug treatment residence, prison/detention center, homeless or unknown place of residence). In addition, in unadjusted analyses we evaluated the impact of maximum social functioning score, depression, injecting and maximum alcohol consumption during treatment on PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence and treatment completion. Social functioning was calculated using a validated scale from the Opiate Treatment Index [27] that addresses employment, residential stability, and interpersonal conflict as well as social support. A higher score reflects poorer social functioning. This scale has been validated among opiate users in Australia (range, 0-48) [27]. Current depression was evaluated using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) [28].

All variables with P<0.20 in bivariate analysis were considered in multivariate logistic regression models using a backwards stepwise approach sequentially eliminated subject to the result of a likelihood ratio test. The impact of HIV infection in these models was also assessed. Statistically significant differences were assessed at p<0.05; p-values are two-sided. All analyses were performed using the statistical package Stata v10.1 (College Station, TX, United States).

RESULTS

Patient Population

Overall, 163 participants were enrolled between June 2004 and February 2008. Among the final analysis population (n=109), 74 HCV participants received PEG-IFN monotherapy and 35 HCV/HIV participants received PEG-IFN/ribavirin therapy.

The baseline characteristics and overall treatment outcomes from the ATAHC study have been published previously [22]. Briefly, among treated participants (Table 1), those with HCV/HIV were older, more often to be male (100% vs. 62%), more often have tertiary education (49% vs. 18%), less often have unstable housing (3% vs. 16%), less often have injected drugs ever (54% vs. 85%), have acquired HCV through sexual contact (63% vs. 5%) and have better social functioning (lower scores, 8 vs. 14).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics among treated HCV and HCV/HIV infected participants with recently acquired HCV infection (n=109)€

| HCV infected (PEG-IFN) (n, %) |

HCV/HIV infected (PEG-IFN/ribavirin) (n, %) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Total participants, (n) | 74 | 35 |

| Male | 46 (62%) | 35 (100%) |

| Mean age in years ±SD | 31.0 ± 9.0 | 42.0 ± 9.5 |

| Tertiary education or greater | 13 (18%) | 17 (49%) |

| Accommodation | ||

| Rent | 44 (60%) | 20 (57% ) |

| Privately owned | 18 (24%) | 14 (40%) |

| Unstable | 12 (16%) | 1 (3%) |

| Full-time or part-time employment | 26 (35%) | 24 (69%) |

| Methadone or buprenorphine treatment | ||

| Ever (not current) | 12 (16%) | 0 (0%) |

| Current | 12 (16%) | 0 (0%) |

| Social functioning score, median (IQR) | 14 (9-19) | 8 (4-13) |

| Current major depression | 7 (10%) | 1 (3%) |

| Mode of infection | ||

| Injecting drug use | 62 (84%) | 13 (37%) |

| Sexual exposure with person(s) of same sex | 1 (1%) | 22 (63%) |

| Sexual exposure with person(s) of opposite sex | 3 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 13 (18%) | 1 (3%) |

| Injecting drug use ever | 63 (85%) | 19 (54%) |

| Mean age at first injection drug use ± SD¥ | 23.0 ± 8.5 | 33.8 ± 10.3 |

| Last time injected†, ¥ | ||

| Within the last month | 27 (43%) | 4 (21%) |

| 1 and 6 months ago | 25 (40%) | 9 (47%) |

| >6 months ago | 11 (18%) | 6 (32%) |

| Drug(s) most frequently injected, (%)†, £ | Opiates (50%) | Methamphetamine (87%) |

| Mean number of days drinking in last month±SD† | 5.6 ± 6.7 | 7.4 ± 8.9 |

| Median Estimated duration of infection in weeks (range) | ||

| Screening | 28 (7-74) | 17 (6-64) |

| Baseline | 34 (18-84) | 30 (10-93) |

| Presentation of recent HC V† | ||

| Acute clinical (symptomatic) | 30 (41%) | 15 (43%) |

| Acute clinical (ALT >400 IU/mL) | 13 (18%) | 11 (31%) |

| Asymptomatic seroconversion | 31 (42%) | 9 (26%) |

| Median log10 HCV RNA (IU/L) - baseline | 5.0 | 5.8 |

| HCV genotype | ||

| Genotype 1 | 41 (54%) | 19 (56%) |

| Genotype 2 | 1 (1%) | 3 (8%) |

| Genotype 3 | 29 (39%) | 12 (34%) |

| Missing | 3 (4%) | 1 (3%) |

two HCV/HIV co-infected participants receiving PEG-IFN monotherapy are excluded from this analysis

at time of screening

denominator is in total number of people reporting documented illness

among those having reported injecting ever

among those having injected in the last 6 months

Among participants with HCV/HIV (n=35), 77% (n=27) had a history of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and 63% (n=22) were receiving HAART at the commencement of HCV treatment. All participants receiving HAART at treatment commencement had HIV RNA suppression <400 copies/mL (22 of 22).

Among treated participants (n=109), 75% reported a history of injecting drug use (n=82). Compared to those not reporting a history of injecting drug use, those with a history of injecting were younger (mean age 32 vs. 41 years), were less often male (73% vs. 81%), have tertiary education or greater (38% vs. 67%), have a privately owned residence (22% vs. 52%) and have full-time or part-time employment (39% vs. 67%).

PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence, on-treatment adherence, dose modification and early treatment discontinuations

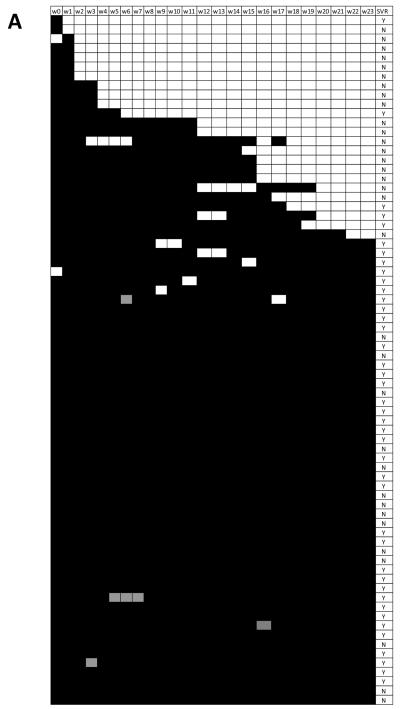

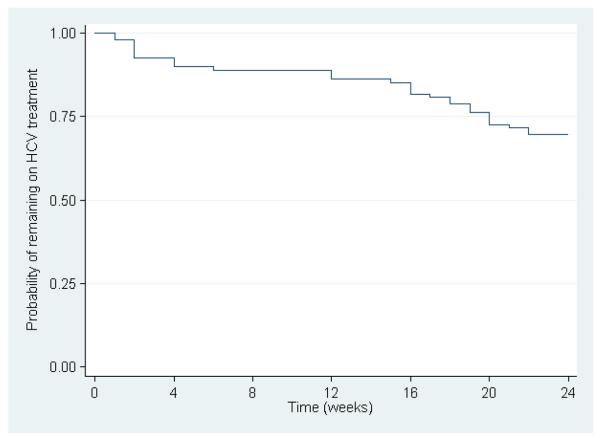

Weekly PEG-IFN adherence among HCV and HCV/HIV participants are shown in Figure 1. The overall proportion with 80/80 PEG-IFN adherence was 82% (89 of 109, Table 2). In total, 14% participants (n=15) missed ≥1 dose of PEG-IFN during treatment (e.g. interrupted weekly therapy, 1 dose, n=10; 2 doses, n=3; 4 doses, n=1; 5 doses, n=1), which translated into an on-treatment adherence of 99% (Table 2). Overall, 95.0% of total PEG-IFN doses were self-administered, 3.3% of doses were administered as directly observed therapy by medical staff and the 1.7% of doses had an unknown mode of administration. PEG-IFN dose modification occurred in 5% (n=5). Further, 30% (n=33) demonstrated discontinuation prior to the per-protocol defined 24 week treatment period. Completion of 0-4, 5-19, 20-23 and all 24 weeks of PEG-IFN therapy occurred in 10% (n=11), 14% (n=15, including six without early virological response at week 12), 6% (n=7) and 70% (n=76), respectively. The mean number of weeks on therapy was 20. The time to treatment PEG-IFN discontinuation is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

PEG-IFN adherence among participants with A) HCV receiving PEG-IFN alone in the ATAHC study (n=74). B) HCV/HIV receiving PEG-IFN and ribavirin in the ATAHC study (n=35). Black boxes represent dose received, grey boxes - dose-reductions and blank boxes - no dose received. SVR, sustained virologic response; Y, yes; N, no.

Table 2.

Adherence to PEG-IFN among treated HCV and HCV/HIV infected participants with recently acquired HCV infection (n=109)

| Overall (n=109) |

HCV (n=74) |

HCV/HIV (n=35) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence, n (%) | 89 (82) | 57 (77) | 32 (91) |

| Mean on-treatment PEG-IFN adherence, (%) | 99.4 | 98.0 | 99.5 |

| Missed doses of PEG-IFN, n (%) | |||

| No missed doses | 94 (86) | 63 (85) | 31 (89) |

| 1 missed dose | 10 (9) | 6 (8) | 4 (11) |

| 2-5 missed doses | 5 (5) | 5 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Number of weeks of PEG-IFN therapy, n (%) | |||

| 24 weeks | 76 (70) | 50 (68) | 26 (74) |

| 20 to 23 weeks | 7 (6) | 3 (4) | 4 (11) |

| 10 to 19 weeks | 15 (14) | 11 (15) | 4 (11) |

| 0 to 9 weeks | 11 (10) | 10 (14) | 1 (3) |

| Weeks on PEG-IFN therapy | |||

| Mean, n (SD) | 20 (6.9) | 19.6 (7.7) | 22.1 (4.4) |

| Median, n (IQR) | 24 (20-24) | 24 (18-24) | 24 (22-24) |

| PEG-IFN dose-modification | 5 (5) | 4 (5) | 1 (3) |

SD=standard deviation; IQR=interquartile range.

Figure 2.

Time to treatment discontinuation among treated participants in the ATAHC study (n=109)

Among HCV and HCV/HIV participants, the proportion discontinuing treatment prior to 24 weeks were 32% (24 of 75) and 26% (9 of 35, P=0.627), respectively. Reasons for discontinuing prior to 24 weeks included physician-directed early termination (HCV, n=1; HCV/HIV, n=0), patient unwillingness to continue (HCV, n=4; HCV/HIV, n=3), virological non-response (HCV, n=5; HCV/HIV, n=2), lost to follow-up (HCV, n=6; HCV/HIV, n=0); side effects (HCV, n=4; HCV/HIV, n=3), death (HCV, n=1, HCV/HIV, n=0); and testing HCV RNA positive at screening but negative at treatment commencement [HCV, n=3 (week 2, n=2, week 6, n=1); HCV/HIV, n=1 (week 2, n=1)]. Discontinuations due to side effects were mainly due to mental health (depression, n=3, mood swings, n=1, insomnia, n=2, fatigue/malaise, n=1). Among participants unwilling to continue or lost to follow-up (n=13), 10 had a history of IDU, but only 3 of 10 had injected in the 30 days prior to treatment initiation. Among participants discontinuing therapy prior to reaching 4 weeks (n=11), four were either unwilling to continue or lost to follow-up, three had side effects, one died and three tested HCV RNA positive at screening but negative at treatment commencement.

Adherence to PEG-IFN in HCV and HCV/HIV participants is shown in Table 2. HCV/HIV participants (n=35) demonstrated a higher PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence (91% vs. 77%, P=0.070) and mean number of weeks on therapy (22.1 vs. 19.6 weeks, P=0.073) than HCV participants (n=74), but the proportion with ≥1 missed dose of PEG-IFN were similar (11% vs. 15%, P=0.512).

Participants having (n=82) and not having (n=27) ever used injecting drugs had similar PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence (81% vs. 85%, P=0.776), mean number of weeks on therapy (20.2 vs. 21.0 weeks, P=0.641), proportion who completed 24 weeks of treatment (68% vs. 74%, P=0.636) and proportion with ≥1 missed dose of PEG-IFN (13% vs. 15%, P=0.539). Participants having (n=31) and not having (n=77) used injecting drugs in the 30 days prior to the initiation of HCV treatment also had similar PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence (84% vs. 81%, P=0.685), mean number of weeks on therapy (21.0 vs. 20.1 weeks, P=0.542), proportion who completed 24 weeks of treatment (74% vs. 68%, P=0.497) and proportion with ≥1 missed dose of PEG-IFN (10% vs. 14%, P=0.519).

Lastly, among participants with available follow-up data (n=91), those who used injecting drugs during HCV treatment (n=30, including 10 participants who did not report injecting in the 30 days prior to HCV treatment initiation) demonstrated similar PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence (87% vs. 90%, P=0.724), mean number of weeks on therapy (22.3 vs. 21.8, P=0.611), proportion who completed 24 weeks of treatment (80% vs. 77%, P=0.999) and proportion with ≥1 missed dose of PEG-IFN (20% vs. 11%, P=0.342) in comparison to those who did not use injecting drugs during treatment (n=61). PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence (78% vs. 90%, P=0.568) and proportion who completed 24 weeks of treatment (67% vs. 85%, P=0.339) were marginally lower in those with ≥daily (n=9) as compared to <daily (n=20) IDU during treatment.

Factors associated with PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence

In unadjusted analysis, 80/80 PEG-IFN adherence occurred more often in those with privately owned accommodation and HIV infection, but less often in those with no tertiary education (Table 3). In adjusted analysis, in the overall population, the only factor associated with 80/80 PEG-IFN adherence was tertiary education (Table 4). When also testing for HIV infection in the model, there was no significant change in the estimates of the model (data not shown). Similarly, in adjusted analysis among HCV monoinfected participants, the only factor marginally associated with 80/80 PEG-IFN adherence was tertiary education (Table 4).

Table 3.

Unadjusted potential predictors of PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence among treated HCV and HCV/HIV infected participants with recently acquired HCV infection (n=109)

| Overall (n=109) |

Adherent to >80% of therapy (n=89) |

% | Odds Ratio |

95% | CI | P | P- overall |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 82 | 67 | 82 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Female | 27 | 22 | 81 | 0.99 | 0.32 | 3.02 | 0.979 | - |

| Age (yrs), mean | 34.8 | - | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.07 | 0.521 | - | |

| Tertiary education or greater | ||||||||

| Yes | 49 | 45 | 92 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| No | 60 | 44 | 73 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.79 | 0.018 | - |

| Accommodation | ||||||||

| Rent | 64 | 50 | 78 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Privately owned | 32 | 30 | 94 | 4.20 | 0.89 | 19.77 | 0.069 | 0.115 |

| Unstable | 13 | 9 | 69 | 0.63 | 0.17 | 2.35 | 0.492 | - |

| Full-time or part-time employment | ||||||||

| Yes | 50 | 43 | 86 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| No | 59 | 46 | 78 | 0.58 | 0.21 | 1.58 | 0.284 | - |

| Methadone or buprenorphine treatment | ||||||||

| Ever (not current) | 12 | 10 | 83 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Current | 12 | 8 | 67 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 2.77 | 0.353 | 0.383 |

| Never | 85 | 71 | 84 | 1.01 | 0.20 | 5.14 | 0.986 | - |

| Social functioning score | ||||||||

| ≤9 | 40 | 34 | 85 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| 10 to 16 | 32 | 26 | 81 | 0.76 | 0.22 | 2.65 | 0.672 | 0.875 |

| ≥17 | 25 | 20 | 80 | 0.71 | 0.19 | 2.61 | 0.602 | - |

| Missing | 12 | 9 | 75 | 0.53 | 0.11 | 2.54 | 0.427 | - |

| Current depression | ||||||||

| No | 99 | 80 | 81 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 10 | 9 | 90 | 2.14 | 0.26 | 17.91 | 0.484 | - |

| Injecting drug use ever | ||||||||

| No | 27 | 23 | 85 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 82 | 66 | 80 | 0.72 | 0.22 | 2.37 | 0.586 | - |

| Injection drug use in previous 6 months | ||||||||

| No | 44 | 35 | 80 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 65 | 54 | 83 | 1.26 | 0.47 | 3.36 | 0.641 | - |

| Injection drug use in previous 30 days | ||||||||

| No | 77 | 62 | 81 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 31 | 26 | 84 | 1.26 | 0.41 | 3.82 | 0.685 | - |

| Number of standard drinks per week | ||||||||

| <4 drinks | 66 | 53 | 80 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| ≥4 drinks | 36 | 29 | 81 | 1.02 | 0.36 | 2.83 | 0.976 | - |

| Estimated duration of infection at screening (wks) | ||||||||

| <24 weeks | 51 | 41 | 80 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| ≥24 weeks | 58 | 48 | 83 | 1.17 | 0.44 | 3.09 | 0.750 | - |

| Presentation of recent HCV | ||||||||

| Acute clinical (symptomatic) | 45 | 34 | 76 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Acute clinical (ALT >400 IU/mL) | 24 | 21 | 88 | 2.26 | 0.57 | 9.07 | 0.248 | 0.383 |

| Asymptomatic seroconversion | 40 | 34 | 85 | 1.83 | 0.61 | 5.52 | 0.281 | - |

| HIV infection | ||||||||

| No | 74 | 57 | 77 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 35 | 32 | 91 | 3.18 | 0.87 | 11.69 | 0.081 | - |

Table 4.

Adjusted models of predictors of PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence and completion of 24 weeks of PEG-IFN treatment among the overall (n=109) and HCV mono-infected population (n=74) treated for recently acquired HCV infection

| Adjusted OR |

95% | CI | P | P- overall |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence | |||||

| Overall population (n=109)a | |||||

| Tertiary education or greater | |||||

| Yes | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| No | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.79 | 0.018 | - |

| Accommodation | |||||

| Rent | - | - | - | - | - |

| Privately owned | - | - | - | - | - |

| Unstable | - | - | - | - | - |

| HCV mono-infected population (n=74)b | |||||

| Tertiary education or greater | |||||

| Yes | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| No | 0.32 | 0.08 | 1.23 | 0.096 | - |

| Accommodation | |||||

| Rent | - | - | - | - | - |

| Privately owned | - | - | - | - | - |

| Unstable | - | - | - | - | - |

| Completion of 24 weeks of PEG-IFN treatment | |||||

| Overall population (n=109)c | |||||

| Tertiary education or greater | |||||

| Yes | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| No | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.81 | 0.017 | - |

| Accommodation | |||||

| Rent | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Privately owned | 4.32 | 1.15 | 16.19 | 0.030 | 0.003 |

| Unstable | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.84 | 0.027 | - |

| HCV mono-infected population (n=74)d | |||||

| Tertiary education or greater | |||||

| Yes | - | - | - | - | - |

| No | - | - | - | - | - |

| Accommodation | |||||

| Rent | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Privately owned | 3.35 | 0.67 | 16.72 | 0.140 | 0.003 |

| Unstable | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.60 | 0.008 | - |

Nagelkerkes R-square=0.096, classification rate=82%;

Nagelkerkes R-square=0.065, classification rate=77%;

Nagelkerkes R-square=0.268, classification rate=74%;

Nagelkerkes R-square=0.283, classification rate=76%.

Among those remaining in follow-up (n=91), 80/80 PEG-IFN adherence was similar in those with depression during treatment (87% vs. 87%, P=0.995), injecting in the past 30 days during treatment (87% vs. 90%, P=0.616), maximum alcohol consumption during treatment (<4 vs. ≥4 drinks per week, 88% vs. 89%, P=0.846) and maximum social functioning score during treatment (≤9, 10 to 16, ≥17, 90% vs. 88% vs. 91%, P=0.891).

Factors associated with completion of PEG-IFN treatment

In adjusted analysis, factors associated with completion of all 24 weeks of PEG-IFN treatment included tertiary education and accommodation (Table 4). When also testing for HIV infection in the model, there was no significant change in the estimates of the model (data not shown). Similarly, in adjusted analysis among HCV monoinfected participants, the only factor associated with completion of all 24 weeks of PEG-IFN treatment was accommodation (Table 4).

Among those remaining in follow-up (n=91), treatment completion was similar in those with depression during HCV treatment (76% vs. 75%, P=0.919), injecting in the past 30 days during treatment (80% vs. 77%, P=0.749), maximum alcohol consumption during treatment (<4 vs. ≥4 drinks per week, 81% vs. 75%, P=0.547) and maximum social functioning score during treatment (≤9, 10 to 16, ≥17; 79% vs. 78% vs. 78%, P=0.984).

Impact of PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence, on-treatment adherence and early treatment discontinuation on sustained virologic response

SVR was higher among those with PEG-IFN 80/80 adherence (67%, 60 of 89) as compared to those without (35%, 7 of 20; P=0.007). There was no difference in SVR between those with (73%, 11 of 15) and without missed doses during therapy (60%, 56 of 94; P=0.309). However, compared to the SVR in those receiving all 24 weeks of therapy (76%, n=76), participants with discontinuation of therapy between 0-4 weeks (9%, n=11), 5-19 weeks (33%, n=15) and 20-23 weeks (43%, n=7) had significantly lower SVR (P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates a high adherence to PEG-IFN among HCV and HCV/HIV-infected injecting drug users (IDUs) receiving treatment for recent HCV infection. Factors independently predicting adherence and treatment completion were socio-demographic (education and stable housing), but did not include recent IDU prior to treatment. Further, IDU during treatment did not impact adherence or treatment completion. Lastly, the majority of sub-optimal PEG-IFN exposure in this study was due to early discontinuation of treatment as opposed to missed doses during therapy.

Overall, a high proportion of participants (82%) in this study were ≥80% adherent to PEG-IFN therapy, which is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that 80/80/80 adherence to PEG-IFN/ ribavirin ranges from 62-76% [11-12, 30]. Participants with HCV/HIV demonstrated better adherence to PEG-IFN although this was not statistically significant. Participants with HCV/HIV co-infection were more often infected via sexual transmission (63%) and were more stable across various demographic characteristics compared to those with HCV alone. Further, two-thirds of HCV/HIV participants were receiving HAART at the time of HCV treatment initiation and all participants demonstrated HIV virological control, suggesting high adherence to HAART therapy. Thus, it is possible that HIV patients in this study were more 'educated' or accustomed to the importance of adherence within a treatment regimen, which may explain the trend to higher adherence. A small proportion of patients (14%) had missed ≥1 dose of PEG-IFN during treatment, with two-thirds of these missing only one PEG-IFN dose, thus producing a high (99%) on-treatment PEG-IFN adherence. Previous studies have also demonstrated high on-treatment PEG-IFN adherence rates ranging from 74%-99% [13, 31-34].

Factors independently predicting ≥80% adherence and completion of HCV treatment included education and accommodation. Recent IDU prior to or during treatment was not associated with adherence to PEG-IFN. Previous work has demonstrated that recent IDU prior to or during treatment for chronic HCV was not associated with adherence to PEG-IFN/ribavirin [12]. These data suggest that recent IDU does not influence subsequent adherence to HCV therapy. The only factor associated with adherence to therapy was level of education. Whilst this may simply be a marker of greater social stability, it does raise the question of whether comprehension of the rationale for treatment and treatment side effects may play a part in maximising adherence, and suggests that further focus needs to be given to pre-treatment education and preparation.

The majority of sub-optimal PEG-IFN exposure was due to early treatment discontinuation as opposed to missed doses during therapy. Although the concept of missed doses and non-adherence to therapy is well-described in HIV [14], this has been rarely investigated during treatment for HCV [13-14, 31-34]. Often, 80/80 adherence to HCV treatment is reported, but a distinction is seldom made between the impact of missed doses during treatment and early treatment discontinuation [14]. Developing strategies to improve adherence will require further research to better understand intermittent adherence (missed doses) and early discontinuation of HCV therapy on SVR.

SVR was higher among those with ≥80 PEG-IFN adherence (67% vs. 35%). However, this was mainly driven by early treatment discontinuation as compared to missed doses during therapy. Early treatment discontinuation had a substantial impact on SVR, particularly if treatment was stopped during the first four weeks of treatment (76% for 24 weeks vs. 9% for 0-4 weeks). This suggests that monitoring during the first four weeks of treatment may be particularly important among IDUs to prevent early discontinuation.

This study has some limitations. Adherence was measured by nurse assessment, potentially resulting in an under-reporting of missed doses, thus, overestimating adherence in this study. Adherence data by self-report has been shown to overestimate adherence compared to objective measures such as pill count or electronic monitors [14]. Self-report is subject to both recall bias, and, because of subjects' desire to please clinicians or researchers, reporting bias [14]. It should also be highlighted that HCV/HIV group was different across a broad range of social and demographic characteristics and the small sample size of the co-infected group meant that predictors of adherence were unable to be assessed Further, adherence is very complex and there may have been unmeasured factors (e.g. previous education and experiences with adherence to other medications and patient-doctor relationships) that may have been associated with adherence and treatment completion. Lastly, the small sample size of this study is a limitation. These results should be confirmed in larger, prospective studies using more precise estimates of adherence.

This study demonstrates that PEG-IFN adherence is high among participants with recent HCV infection acquired primarily through IDU. Further, IDU prior to, and during, PEG-IFN treatment was not associated with reduced adherence or treatment completion. These data suggest that adherence is not compromised among IDUs, supporting guidelines that active IDUs should not be excluded from HCV therapy and the decision to initiate HCV treatment in active IDUs should be made case by case [35-37]. Decreased adherence was associated primarily with level of education, and to a lesser extent with other socio behavioural factors. Increased education and support during treatment preparation should be targeted to IDUs prior to treatment. The majority of sub-optimal PEG-IFN exposure was due to early discontinuation as opposed to missed doses during therapy. Directly observed HCV therapy has been shown to be effective in IDUs [38]. Supervised dosing, particularly early in therapy, may provide enhanced engagement with healthcare providers to address social factors and adverse events (e.g. depression) that may lead to early discontinuation. Strategies to enhance adherence will continue to be important, particularly given the potential for drug resistance with the roll-out of directly acting antivirals.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health grant RO1 DA 15999-01. The National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales. Roche Pharmaceuticals supplied financial support for pegylated IFN-alfa-2a/ribavirin. GD, PH and AL were supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Research Fellowships. MH was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Award and a VicHealth Senior Research Fellowship. JK was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Research Fellowship.

List of Abbreviations

- PEG-IFN

pegylated interferon

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- SVR

sustained virological response

- ATAHC

Australian Trial in Acute Hepatitis C

- IDU

injection drug use

- IDUs

injection drug users

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- PEG-IFN

pegylated interferon-α2a

- ITT

intention-to-treat

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: GD, GM and JK have received research support from Roche Pharmaceuticals. GD is on the speaker's bureau for Roche Pharmaceuticals. GD and GM are members of advisory board for Roche Pharmaceuticals. GD and BY have received travel grants from Roche Pharmaceuticals. GD is a consultant/advisor for Schering Plough, Tibotec, and Abbott. JG is a member of an advisory board for Schering-Plough. GM is a consultant/advisor for Schering Plough, Novartis and Astellar.

Author Contributions: Authors GJD, GVM, JMK designed the original ATAHC study and wrote the protocol. Authors JG, GJD and GVM designed the adherence sub-study. Author JG drafted the primary statistical analysis plan, which was reviewed by GJD and GVM. The primary statistical analysis was conducted by JG and additional statistical analyses were conducted by JG and GJD. All authors reviewed data analysis. Authors JG and GJD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Goncales FL, Jr., Haussinger D, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Jr., Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, Ramadori G, et al. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346–355. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torriani FJ, Rodriguez-Torres M, Rockstroh JK, Lissen E, Gonzalez-Garcia J, Lazzarin A, Carosi G, et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:438–450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung RT, Andersen J, Volberding P, Robbins GK, Liu T, Sherman KE, Peters MG, et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a plus ribavirin versus interferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C in HIV-coinfected persons. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:451–459. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen DM, Morgan TR, Marcellin P, Pockros PJ, Reddy KR, Hadziyannis SJ, Ferenci P, et al. Early identification of HCV genotype 1 patients responding to 24 weeks peginterferon alpha-2a (40 kd)/ribavirin therapy. Hepatology. 2006;43:954–960. doi: 10.1002/hep.21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neumann AU, Pianko S, Zeuzem S, Yoshida EM, Benhamou Y, Mishan M, McHutchison JG, et al. Positive and negative prediction of sustained virologic response at weeks 2 and 4 of treatment with albinterferon alfa-2b or peginterferon alfa-2a in treatment-naive patients with genotype 1, chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2009;51:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, Heinzen EL, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399–401. doi: 10.1038/nature08309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg T, Weltman M, Abate ML, Bassendine M, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1100–1104. doi: 10.1038/ng.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Kurosaki M, Matsuura K, Sakamoto N, Nakagawa M, et al. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/ng.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McHutchison JG, Manns M, Patel K, Poynard T, Lindsay KL, Trepo C, Dienstag J, et al. Adherence to combination therapy enhances sustained response in genotype-1-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1061–1069. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sylvestre DL, Clements BJ. Adherence to hepatitis C treatment in recovering heroin users maintained on methadone. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:741–747. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3281bcb8d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo Re V, 3rd, Amorosa VK, Localio AR, O'Flynn R, Teal V, Dorey-Stein Z, Kostman JR, et al. Adherence to hepatitis C virus therapy and early virologic outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:186–193. doi: 10.1086/595685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss JJ, Brau N, Stivala A, Swan T, Fishbein D. Review article: adherence to medication for chronic hepatitis C - building on the model of human immunodeficiency virus antiretroviral adherence research. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:14–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calleri G, Cariti G, Gaiottino F, De Rosa FG, Bargiacchi O, Audagnotto S, Quaglia S, et al. A short course of pegylated interferon-alpha in acute HCV hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:116–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broers B, Helbling B, Francois A, Schmid P, Chuard C, Hadengue A, Negro F. Barriers to interferon-alpha therapy are higher in intravenous drug users than in other patients with acute hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2005;42:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamal SM, Ismail A, Graham CS, He Q, Rasenack JW, Peters T, Tawil AA, et al. Pegylated interferon alpha therapy in acute hepatitis C: relation to hepatitis C virus-specific T cell response kinetics. Hepatology. 2004;39:1721–1731. doi: 10.1002/hep.20266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamal SM, Moustafa KN, Chen J, Fehr J, Abdel Moneim A, Khalifa KE, El Gohary LA, et al. Duration of peginterferon therapy in acute hepatitis C: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2006;43:923–931. doi: 10.1002/hep.21197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamal SM, Fouly AE, Kamel RR, Hockenjos B, Al Tawil A, Khalifa KE, He Q, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b therapy in acute hepatitis C: impact of onset of therapy on sustained virologic response. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:632–638. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santantonio T, Fasano M, Sinisi E, Guastadisegni A, Casalino C, Mazzola M, Francavilla R, et al. Efficacy of a 24-week course of PEG-interferon alpha-2b monotherapy in patients with acute hepatitis C after failure of spontaneous clearance. J Hepatol. 2005;42:329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiegand J, Buggisch P, Boecher W, Zeuzem S, Gelbmann CM, Berg T, Kauffmann W, et al. Early monotherapy with pegylated interferon alpha-2b for acute hepatitis C infection: the HEP-NET acute-HCV-II study. Hepatology. 2006;43:250–256. doi: 10.1002/hep.21043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dore GJ, Hellard M, Matthews GV, Grebely J, Haber PS, Petoumenos K, Yeung B, et al. Effective treatment of injecting drug users with recently acquired hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:123–135. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.019. e121-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vogel M, Nattermann J, Baumgarten A, Klausen G, Bieniek B, Schewe K, Jessen H, et al. Pegylated interferon-alpha for the treatment of sexually transmitted acute hepatitis C in HIV-infected individuals. Antivir Ther. 2006;11:1097–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilleece YC, Browne RE, Asboe D, Atkins M, Mandalia S, Bower M, Gazzard BG, et al. Transmission of hepatitis C virus among HIV-positive homosexual men and response to a 24-week course of pegylated interferon and ribavirin. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:41–46. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000174930.64145.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grebely J, deVlaming S, Duncan F, Viljoen M, Conway B. Current approaches to HCV infection in current and former injection drug users. J Addict Dis. 2008;27:25–35. doi: 10.1300/J069v27n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hellard M, Sacks-Davis R, Gold J. Hepatitis C treatment for injection drug users: a review of the available evidence. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:561–573. doi: 10.1086/600304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darke S, Hall W, Wodak A, Heather N, Ward J. Development and validation of a multidimensional instrument for assessing outcome of treatment among opiate users: the Opiate Treatment Index. Br J Addict. 1992;87:733–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. quiz 34-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44:227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sola R, Galeras JA, Montoliu S, Tural C, Force L, Torra S, Montull S, et al. Poor response to hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapy in HIV- and HCV-coinfected patients is not due to lower adherence to treatment. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:393–400. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fumaz CR, Munoz-Moreno JA, Ballesteros AL, Paredes R, Ferrer MJ, Salas A, Fuster D, et al. Influence of the type of pegylated interferon on the onset of depressive and neuropsychiatric symptoms in HIV-HCV coinfected patients. AIDS Care. 2007;19:138–145. doi: 10.1080/09540120600645539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith SR, Wahed AS, Kelley SS, Conjeevaram HS, Robuck PR, Fried MW. Assessing the validity of self-reported medication adherence in hepatitis C treatment. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1116–1123. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss JJ, Bhatti L, Dieterich DT, Edlin BR, Fishbein DA, Goetz MB, Yu K, et al. Hepatitis C patients' self-reported adherence to pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03718.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cacoub P, Ouzan D, Melin P, Lang JP, Rotily M, Fontanges T, Varastet M, et al. Patient education improves adherence to peg-interferon and ribavirin in chronic genotype 2 or 3 hepatitis C virus infection: a prospective, real-life, observational study. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6195–6203. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swan T, Curry J. Comment on the updated AASLD practice guidelines for the diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: treating active drug users. Hepatology. 2009;50:323–324. doi: 10.1002/hep.23077. author reply 324-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335–1374. doi: 10.1002/hep.22759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherman M, Shafran S, Burak K, Doucette K, Wong W, Girgrah N, Yoshida E, et al. Management of chronic hepatitis C: consensus guidelines. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21(Suppl C):25C–34C. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grebely J, Raffa JD, Meagher C, Duncan F, Genoway KA, Khara M, McLean M, et al. Directly observed therapy for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in current and former injection drug users. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1519–1525. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]