Abstract

Background

Patients with diabetes and depression often have self-management needs that require between-visit support. This study evaluated the impact of telephone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) targeting patients’ management of depressive symptoms, physical activity levels, and diabetes-related outcomes.

Methods

291 patients with type 2 diabetes and significant depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory scores ≥14)were recruited from a community-university-and VA healthcare system. A manualized telephone CBT program was delivered by nurses weekly for 12weeks, followed by nine monthly booster sessions. Sessions initially focused exclusively on patients’ depression management and then added a pedometer-based walking program. The primary outcome was hemoglobin A1cmeasured at 12-months. Blood pressure was a secondary outcome; levels of physical activity were determined by pedometer readings; depression, coping, and health related quality of life (HRQL) were measured using standardized scales.

Results

Baseline A1c levels were relatively good and there was no difference in A1c at follow-up. Intervention patients experienced a4.26 mmHg decrease in systolic blood pressure relative to controls (p=.05). Intervention patients had significantly greater increases in step-counts (mean difference 1,131 steps/day; p=.0002) and greater reductions in depressive symptoms (58%remitted at12 months versus 39%; p=.002). Intervention patients also experienced relative improvements in coping and HRQL.

Conclusions

This program of telephone delivered CBT combined with a pedometer-based walking program did not improve A1c values but significantly decreased patients’ blood pressure, increased physical activity, and decreased depressive symptoms. The intervention also improved patients’ functioning and quality of life.

Introduction

In the U.S., 18% of men and 28% of women with diabetes suffer from significant depressive symptoms.1 Depressed patients with diabetes are less likely to respond to depression care and more likely to have recurrences of their symptoms than other depressed patients.2 Diabetes patients with depression have poorer diabetes outcomes,3–6 and studies have linked depression to diabetes patients’ self-care behaviors, including medication adherence and physical activity.7–10

Earlier small trials with promising findings indicated that depression-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) as well as antidepressant medications might improve patients’ glycemic control.11,12 Although one study has shown important long-term impacts on medical costs,13 subgroup analyses of diabetes participants in larger depression treatment trials and studies examining depression-focused interventions specifically among patients with diabetes have not demonstrated improvements in diabetes-related outcomes.14–16 These studies suggest that treating depression among diabetes patients may be a necessary, but not sufficient step in improving their clinical management.17 Many researchers and clinicians now believe that patients with diabetes and depression are a prototype of complex, multi-morbid patients who may require more intensive between-visit follow-up to improve their self-management and outcomes. Unfortunately, depression often is not treated due to the many competing clinical demands that diabetes patients present.18,19

Prior to initiating the current trial, we developed a conceptual framework defining the potential linkages between depression management and diabetes-related outcomes.20 We noted that CBT might be a particularly useful approach for improving both patients’ diabetes outcomes and their depressive symptoms. As is the case for antidepressant pharmacotherapy, CBT significantly improves depressive symptoms, and several trials suggest that the benefits of CBT may continue longer than antidepressant medication once treatment is discontinued.21 Moreover, CBT directly addresses the cognitive distortions and other thought processes that might inhibit effective diabetes self-care. These collateral benefits of CBT may be particularly important, since recent studies suggest that diabetes-specific distress may be a more direct cause of poor glycemic control than depressive symptoms per se.22

Physical activity is a key behavior around which to focus a specialized CBT program for patients with diabetes and depression,20 because it directly addresses both patients’ mood disorder and their diabetes-related physiologic control.23–26 Pedometer-based physical activity programs provide an objective measure of patients’ behavior for evaluating intervention effects, and they also provide ready feedback to individuals for behavioral goal setting and monitoring progress toward those goals. A meta-analysis concluded that pedometer-based walking programs can significantly increase activity levels and improve blood pressures.27

Here, we report the main 12-month outcomes of a telephone-delivered CBT program designed to promote physical activity and address depressive symptoms among patients with comorbid depression and type 2 diabetes. The primary outcome for the trial was patients’ glycemic control. Secondary outcomes included blood pressure, depressive symptoms, objectively-measured physical activity levels, and diabetes-related self-management beliefs. To increase generalizability, the trial included patients from three different health systems.

Methods

Setting and Sample

Participants were identified between March 2006 and November 2008 from: a community-based non-profit healthcare system, a university healthcare system, and a VA healthcare system. All three systems served as teaching sites for affiliated medical schools. Within each site, patients were identified from several primary care clinics. Additional patients (5% of patients ultimately enrolled) were identified after a visit to the community health system’s diabetes learning center. Potential participants were at least 21 years old and were identified via electronic records based on a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes plus a prescription for antihyperglycemic medication. Additional patients were self-referred based on advertisements and newsletters. After initial identification, patients were screened for eligibility via phone. At the time of telephone screening, patients were excluded if they had a Patient Health Questionnaire-Nine (PHQ-9)28 depression score of < 11, were not using antihyperglycemic medication, had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, or were in active treatment for another serious illness such as severe heart failure, severe COPD, or ESRD. Patients using antidepressant medication at the time of the screening were excluded if they reported a change in the prior 30 days in either their antidepressant medication or the physician prescribing their antidepressants. Additional patients were excluded if they reported that they were unable to walk either one block or 10 minutes without rest. Prior physician authorization to participate was required for patients reporting that: their physician recommended only medically supervised physical activity in the last six months; they experienced chest pain as the result of moderate physical activity; or they experienced significant dizziness leading to falls or unconsciousness.

Patients who were eligible and interested during the telephone screening were invited to an in-person screening and recruitment visit. Patients were excluded if: they had a Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)29 score < 14, they scored < 21 on the Short Orientation Memory Concentration Test,30 or they reported drug or alcohol problems during the prior three months as measured by a modified version of the CAGE questionnaire.31 All patients completed a written informed consent. The study was approved by the IRB in each of the three participating health care systems.

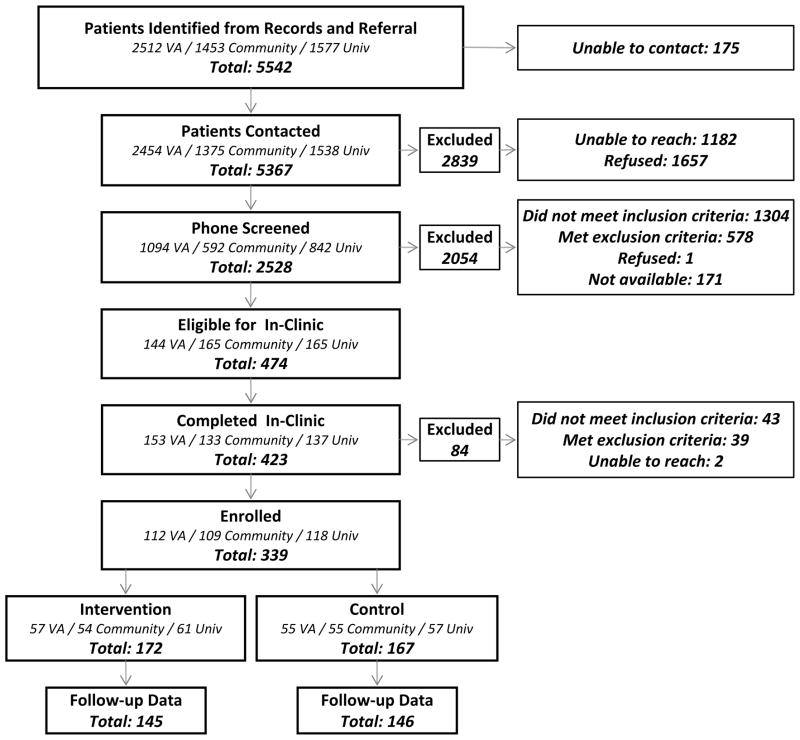

A total of 5,542 patients were identified from electronic records, of which 474 (8.6%) were found to be eligible during telephone screening (figure). A total of 339 patients were enrolled in the trial, of whom 291 (86%) provided A1c, blood pressure, and survey data at the 12-month follow-up. Patients who failed to provide these follow-up data were similar on a large number of measures (including all outcomes presented here) but were somewhat more satisfied at baseline with their healthcare (p<.05). Of those providing in-person follow-up data, 214 (74%) provided both baseline and follow-up pedometer data. Those without stepcount data had lower incomes, higher systolic blood pressures, and higher (i.e., worse) BDI scores at baseline.

Figure 1.

Recruitment Diagram

Notes: VA = VA healthcare system. Community = community-based healthcare system. Univ = university-based healthcare system.

Randomization

After completing their informed consent and baseline survey, enrolled patients were randomized to the intervention or usual care. Randomization was conducted in blocks defined by patients’ healthcare system and whether or not the patient was self-referred. Random assignment was determined using sealed envelopes prepared by the research team and a table of random numbers.

Intervention

Intervention patients participated in a 12-month telephone-delivered CBT program. CBT was delivered by nurses with a mix of prior psychiatric and primary care training and experience, who were further trained in CBT (see below). The CBT program included an initial intensive phase of 12-weekly sessions followed by nine monthly booster sessions. At first, CBT focused exclusively on patients’ depressive symptoms; after five sessions, nurse counselors introduced concepts related to a pedometer-based walking program, and the links between depression, physical activity, and diabetes outcomes.

Several elements of the CBT program were designed to ensure fidelity across nurses and over time: Prior to initiating patient counseling, each nurse participated in an intensive training program including a six-session CBT course. Nurses also participated in weekly group supervisory sessions, where they discussed problematic cases and shared information about strategies for completing the CBT protocol. Each nurse audio-recorded initial sessions with their patients, and those recordings were reviewed by an experienced CBT supervisor and trainer during group supervision. Both nurses and patients used a week-by-week manual to guide their sessions. The manual was designed to be visually engaging and included elements common in depression CBT manuals plus additional concepts related to diabetes self-care and physical activity. Nurse manuals included check-lists for each week’s CBT goals. During each session, nurses monitored patients’ depressive symptoms using the PHQ and their activity levels using the PASE.28,32 Patient manuals included logs that they could use to complete CBT homework exercises and to monitor their progress toward step-count goals.

While intervention nurses were trained to work relatively independently, several aspects of the protocol ensured communication with patients’ primary care teams: Primary care providers (PCPs) were identified for each participant, and that provider was sent an introductory letter from the intervention nursing team after recruitment including the patient’s BDI score and interpretation. Patients’ participation was always noted in their medical record. PCPs received summary fax reports about patients’ PHQ scores every three months with more frequent reports noting significant changes. PCPs were alerted by fax and phone in the event that the patient reported: suicidal ideation, discontinuing antidepressant medication on their own, persistent elevated depressive symptoms, or a need for a prescription refill. Additional contacts between intervention nurses (e.g., to discuss other patient health problems) were at the nurses’ discretion.

Enhanced Usual Care

Usual care patients received: a copy of the Feeling Good Handbook -a self-help book based on cognitive behavioral therapy for depression,33 National Institute of Mental Health educational materials about depression, educational materials about walking and diabetes, and a list of local resources for depression. If usual care patients allowed, their primary care physician was notified about their depression scores.

Measurement

Patients completed in-person interviews at baseline and 12-months. At both time points, their A1c was measured using the DCA2000 point-of-care analyzer.34 Blood pressure was measured in both arms with a repeat measurement in the arm with the highest pressure after several minutes of rest. This third measure was used in study analyses.

Six weeks after completing their baseline assessment, all patients were sent an Omron HJ-720 ITC pedometer with a built-in clock and electronic memory. Pedometers were sent blinded using a removable sticker, and patients were instructed to wear the pedometer throughout waking hours for seven consecutive days. At the end of the week, patients were instructed to remove the sticker and contact the study team to report their step-counts. Those who did not call the team were contacted by research staff. Control-group patients then returned the pedometer; intervention patients were instructed to keep the pedometer for use in their walking program. At the 12 month follow-up, all control patients as well as intervention patients who had lost their pedometer were again sent a blinded pedometer with similar instructions.

Psychometric Scales and Variables

The main depression outcome measure was the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).29 As with prior studies,35 we calculated the average BDI score for each study group as well as the proportion of patients in each group with remitted depression (i.e., BDI scores < 14). Potential proximal outcomes identified from our conceptual model,20 were measured using validated scales: Patients’ coping was measured using the Brief Cope (alpha = .89in this dataset),36 and perceived self-efficacy for physical activity and diet were measured using the Perceived Competence Scale(alphas=.90and .89, respectively).37,38 Adherence to antihyperglycemic medication and (for those using antidepressants) to their antidepressant medications were measured using the Morisky medication adherence scale.39 We also measured patients’ beliefs about the benefits and potential negative consequences of diabetes medications using the Beliefs about Medications Questionnaire.40 Patients’ health-related quality of life was measured using the SF-12.41

Analysis

The primary outcome was change in A1c levels, and the sample size was designed to have80% power to identify a .5% absolute difference across groups in A1c (e.g., a difference between an A1c of 8.5% and 8.0%), assuming a type 1 error rate of .05. All analyses were conducted with participants assigned to the groups to which they were randomized (i.e., based on intention-to-treat). Outcomes were examined using linear and logistic regression models that controlled for baseline values.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of the Sample

Thirty percent of enrollees were recruited from the community clinic site, 36% from the university site, and 34% from the VA. There were no significant differences at baseline in intervention and control patients’ sociodemographic characteristics or antihyperglycemic/ antidepressant medication use (Table 1); A1cs, blood pressures, depressive symptoms, or survey-based outcomes (Tables 2–3). Patients’ mean age was56 years, half were women, and 84% were White. Roughly a third of participants (32%) had no more than a high school education, while 22% had a bachelor’s degree or more. Most participants were either unemployed/disabled (36%) or retired (27%).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Sample

| Overall | Usual Care | CBT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 291 | 146 | 145 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 56.0 ± 10.1 | 56.0±10.9 | 55.1± 9.4 |

| Female (%) | 51.5 | 50 | 51 |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 84 | 84 | 84 |

| Black | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Other | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Married/Partnered (%) | 58 | 54 | 62 |

| Education(%) | |||

| High School or Less | 32 | 37 | 27 |

| Some college | 46 | 39 | 52 |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 22 | 24 | 20 |

| Employment Status (%) | |||

| Employed FT/PT | 38 | 39 | 37 |

| Unemployed/disabled | 36 | 36 | 35 |

| Retired | 27 | 25 | 28 |

| Annual Household Income (%) | |||

| < $10,000 | 30 | 34 | 25 |

| $10,000–$40,000 | 37 | 36 | 37 |

| > $40,000 | 33 | 30 | 39 |

| Body Mass Index(mean ± SD) | 37.6 ± 8.8 | 38.0 ± 9.3 | 37.3 ± 8.3 |

| Diabetes Medications (%) | |||

| Insulin only | 13 | 14 | 10 |

| Oral agents only | 63 | 63 | 65 |

| Insulin plus oral agents | 24 | 23 | 25 |

| Antidepressant medication (%) | 57 | 57 | 57 |

Table 2.

Changes in Step-Counts, Depressive Symptoms, and other Proximal Endpoints

| Baseline | 12-Months | P- value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual Care | CBT | Usual Care | CBT | (Between Group Difference (95% CI) | ||

| Step Counts | 3139 ± 2361 | 3226 ± 1860 | 3314 ± 2516 | 4499 ± 2612* | 1131 (535 to 1728) | .0002 |

| Beck Depression Inventory(↓ better) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 26.5 ± 9.9 | 26.7 ± 7.7 | 18.6 ± 10.7* | 14.2 ± 10.3* | −4.5 (−6.7 to −2.4) | <.0001 |

| % < 14 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 58 | −2.1 (−3.4 to −.74) | .002 |

| % > 29 | 34 | 32 | 18 | 10 | −4.9 (−9.7 to −.08) | .05 |

| Coping Orientation(↑ better) | 64.7 ± 10.5 | 64.8 ± 10.3 | 77.2 ± 12.8* | 80.8 ± 12.3* | 3.2 (.71 to 5.7) | .012 |

| Perceived Competence(↓ better) | ||||||

| Overall | 19.1 ± 5.3 | 19.3 ± 5.1 | 20.0 ± 6.4 | 18.4 ± 5.6 | −1.6 (−2.9 to −.36) | .01 |

| Physical Activity Subscale | 9.3 ± 3.1 | 9.6 ± 3.1 | 10.7 ± 4.0 | 9.3 ± 3.4 | −1.4 (−2.3 to −.6) | .0006 |

| Dietary Subscale | 9.8 ± 3.4 | 9.7 ± 3.4 | 9.3 ± 3.5 | 9.1 ± 3.6 | −.17 (−.9 to .56) | .64 |

| Medication Adherence(↑ better) | ||||||

| Diabetes Medications | 8.5 ± 1.0 | 8.4 ± 0.7 | 8.6 ± 1.0 | 8.6 ± 1.0 | −.04 (−.24 to .16) | .7 |

| Depression Medications | 8.7 ± 0.9 | 8.6 ± 1.1 | 8.9 ± 1.0 | 8.9 ± 1.0 | .05 (−.25 to .35) | .8 |

| Beliefs About Medications | ||||||

| Overall (↑greater net benefit) | 30.0 ± 6.7 | 30.1 ± 5.9 | 31.1 ± 6.1 | 30.8 ± 5.9 | −.36 (−1.6 to .87) | .6 |

| Necessity (↓greater need) | 10.3 ± 4.1 | 10.7 ± 3.8 | 10.4 ± 3.9 | 10.7 ± 4.2 | −.004 (−.78 to .77) | 1.0 |

| Concerns (↓ greater concern) | 19.7 ± 4.9 | 19.3 ± 4.6 | 20.7 ± 4.6 | 20.1 ± 5.1 | −.38 (−1.4 to .59) | .4 |

Notes: Asterisks indicate a significant (p<.05) within group change between baseline and follow-up.

Table 3.

Changes in A1c, Blood Pressure, and Health-Related Quality of Life

| Baseline | 12-Months | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual Care | CBT | Usual Care | CBT | Between Group Difference (95% CI) | ||

| Hemoglobin A1c | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 7.7 ± 1.7 | 7.5 ± 1.7 | 7.7 ± 1.7 | 7.7 ± 1.8 | .07 (−.26 to .40) | .7 |

| Proportion < 8% | 68% | 72% | 66% | 72% | .11 (−.24 to .46) | .54 |

| Systolic BP | ||||||

| Mean SD | 133.8 ± 16.4 | 136.0 ± 17.0 | 134.2 ± 20.6 | 130.8 ± 17.7* | −4.26 (−8.5 to −.06) | .05 |

| Proportion < 130 mmHg | 44% | 38% | 47% | 50% | −2.0 (−8.4 to 4.4) | .53 |

| Diastolic BP | ||||||

| Mean SD | 79.6 ± 11.1 | 79.8 ± 10.4 | 78.2 ± 10.6 | 76.4 ± 11.4* | −1.8 (−4.1 to .47) | .12 |

| Proportion < 80 mmHg | 51% | 49% | 62% | 59% | −2.7 (−6.2 to .78) | .13 |

| Quality of Life (SF-12) | ||||||

| Mental Composite | 38.2 ± 11.0 | 36.8 ± 10.8 | 44.5 ± 11.8 * | 44.7 ± 12.1* | 3.5 (.82to 6.1) | .01 |

| Physical Composite | 38.0 ± 11.8 | 39.4 ± 11.4 | 35.8 ± 12.0 | 38.2 ± 12.0 | 1.2(−.97 to 3.3) | .3 |

| Physical Functioning | 39.8 ± 11.8 | 40.0 ± 11.6 | 36.3 ± 12.2* | 39.5 ± 11.7 | 3.0 (.92 to 5.2) | .005 |

| Mental Functioning | 38.2 ± 10.1 | 37.2 ± 9.7 | 43.7 ± 11.4* | 46.7 ± 11.3* | 3.4 (.97 to 5.89) | .006 |

| Emotional Role Limitations | 38.8 ± 10.7 | 36.8 ± 10.5 | 40.8 ± 11.6 | 44.2 ± 10.6* | 3.9 (1.4 to 6.4) | .002 |

| Social Functioning | 36.4 ± 11.7 | 37.8 ± 10.5 | 41.1 ± 13.1* | 43.8 ± 12.7 | 2.4 (−.5 to 5.2) | .1 |

| Vitality | 37.5 ± 8.1 | 37.3 ± 7.9 | 40.7 ± 9.8* | 43.7 ± 11.2* | 3.0 (.78 to 5.2) | .008 |

| General Health | 34.3 ± 11.1 | 34.8 ± 10.5 | 37.2 ± 11.7* | 39.5 ± 11.8* | 2.0 (−.25 to 4.3) | .08 |

| Pain | 37.5 ± 13.6 | 38.5 ± 12.8 | 38.4 ± 13.9 | 39.4 ± 12.7 | .54 (−2.2 to 3.3) | .7 |

| Physical Role Limitations | 37.6 ± 10.7 | 38.5 ± 10.1 | 37.8 ± 10.6 | 41.5 ± 11.0* | 3.0 (.94 to 5.0) | .004 |

Notes: Asterisks indicate a significant (p<.05) within group change between baseline and follow-up.

Engagement in the Intervention

On average, intervention patients completed 13.5 out of a possible 21 telephone CBT sessions with their nurse counselor, with half of participants completing 17 sessions or more (interquartile range: 5 – 20). Ten percent of intervention participants completed no more than 1 telephone counseling session.

Changes in A1c, Blood Pressures, and Health-Related Quality of Life (Table 3)

Patients at baseline had relatively good glycemic control, with 70% of patients at baseline having an A1c < 8%. There was no significant between-group difference in A1c at follow-up. However, relative to enhanced usual care patients, intervention patients experienced a significant (p= .05) 4.26 mmHg average reduction in their systolic blood pressures. A similar relative decrease (4.71 mmHg) was observed in the subgroup of patients with both baseline and follow-up step-count data. In the subgroup of patients with a baseline systolic blood pressure over the recommended threshold for diabetes patients of 130 mmHg,42 intervention patients experienced an average 5.88 mmHg reduction relative to control patients (p=.05). There was no statistically significant difference in diastolic blood pressures at follow-up in the overall sample. However, within the subgroup that had baseline diastolic blood pressures higher than the recommended cutoff of 80 mmHg, intervention patients experienced a relative 6.1 mmHg reduction relative to controls (p=.03).

There was a significant improvement in the SF-12 mental composite summary score in the intervention group relative to those receiving enhanced usual care (p=.01). Although there was not a significant difference across groups in the Physical Composite Summary (p=.28), there were significant differences in some physically-weighted subcales of the SF-12. For example, while the control group experienced a significant decline in physical functioning between baseline and follow-up, there was no concomitant decline in the intervention group, yielding a significant between-group difference in 12 month scores when controlling for baseline values. Patients’ role limitations due to physical functioning improved significantly in the intervention group but did not improve among control patients.

Changes in Step Counts, Depressive Symptoms, and Other Proximal Outcomes

Both intervention and control groups had low levels of physical activity at baseline (roughly 3000 steps per day) with no significant differences between the groups. At follow-up, intervention patients experienced a 1,131 average daily step-count increase, relative to the small, non-significant change in the control group (p<.0002, Table 2). Both intervention and control groups experienced a significant (p<.05) improvement in their average BDI depression scores, with a 4.54 point greater average improvement in the intervention than control group (p<.0001). At12-months, 58% of intervention patients’ depression remitted (BDI scores < 14) compared to 39% of controls (p = .002), and significantly fewer intervention than control patients met criteria for severe depression (BDI > 29, 10% versus 18%, p=.05). In the subgroup of participants with step-count data, 72% of CBT patients compared to 45% of control patients had remitted depression at follow-up (p<.0001).

As shown in Table 2, intervention patients reported significant improvements in their coping skills and increases in their self-efficacy for increasing their physical activity levels at follow-up (both p<.05). There was no significant difference in changes in patients’ self-reported antidepressant or antihyperglycemic medication adherence at follow-up, nor in patients’ beliefs regarding the potential efficacy or concerns about their medication for diabetes.

Discussion

In this multisite randomized trial of telephone counseling for patients with diabetes and comorbid depression, hemoglobin A1c values (the study’s primary outcome) were reasonably good at the beginning of the study and unaffected by intervention participation. The nurse delivered CBT intervention first emphasized management of depressive symptoms and later emphasized physical activity, and was successful in:reducing depressive symptoms, improving self-efficacy and other supportive coping-related cognitions, increasing physical activity, and decreasing patients’ blood pressures. Temporal trends in diabetes patients’ glycemic control over recent years43 make it difficult to see further impacts on this outcome. These results support the idea that treating depression alone may be a necessary but not sufficient step in improving diabetes patients’ clinical management and self-care.

Blood pressure is a particularly important outcome for patients with diabetes and depression, as it is more closely associated with subsequent vascular events and mortality than is hyperglycemia.44 Therefore, our finding of reduced blood pressure along with improved depressive symptoms is of particular interest and may have implications for longer term complications. To our knowledge, only one prior trial of pharmacologic treatment for depressed diabetes patients examined potential impacts on blood pressure control.45 Like the current study, that trial also reported a significant impact on systolic pressures.

This intervention differed from prior CBT-based services for depressed diabetes patients both in its duration and in its focus on promoting physical activity. The intervention in this study included both a 12 week intensive delivery phase during which CBT sessions occurred weekly, and an additional 9 month period during which booster sessions were provided monthly. Similar to the intervention in the Pathways study,15 nurse follow up continued for up to 12 months but CBT sessions occurred throughout the 12 month period regardless of whether symptoms persisted. Potentially, patients need booster CBT sessions over a longer period of time with a dual focus on depressive symptoms and physical activity if important diabetes-related outcomes, such as blood pressure, are to be impacted.

Results of this study show that the combination of telephone-based CBT and a pedometer-based walking program can support safe and effective sustained engagement in an unsupervised walking program among individuals with diabetes and depression. The absolute increase in physical activity of 1,131 steps per day translates into approximately four additional miles of walking per week or 96 minutes of physical activity per week at 2.5 miles per hour. The emphasis on both depression and increasing physical activity may be one of the explanations for demonstrated impacts on both depression and blood pressure.46,47 A 2009 NIH meeting on the Science of Behavior Change acknowledged the idea that risk behaviors often occur in “bundles” and the importance of focusing on clusters that may have common underlying processes.48 This study intervention took advantage of common theoretical and technical aspects of treatment (i.e., the use of CBT to address thought patterns underlying depressive symptoms and lack of self-efficacy for physical activity) and honed patients’ skills applicable to multiple risk factors. This combined approach may result in more convenient, efficient, and effective interventions.

The CBT intervention used in this study may be applicable to many health care settings. Intervention nurses received training and weekly group supervision that could potentially be provided to primary care-based nurses with limited time. The telephone format also decreased infrastructure requirements as well as travel and time burden for patients. Possibly as a result of the convenience and flexibility of the telephone format, patient engagement levels (as measured by the number of completed sessions) were high relative to many CBT interventions relying on face-to-face encounters.49–51 Because both patients and clinicians used detailed, structured manuals, the service could be provided consistently across providers, while allowing trained nurses appropriate discretion to tailor the service to individual patient needs.52 These benefits notwithstanding, supervision by a mental health professional with expertise in CBT as well as close integration with primary care is important to insure that complications are avoided and well managed for this complex population. In the current study, initial sessions for each nurse were recorded and those recordings were reviewed by the CBT supervisor and discussed during regular meetings. Nevertheless, a formal fidelity assessment of CBT elements was not done, and this is a potential weakness of the current trial.

As already noted, the study’s primary outcome, A1c, was not impacted by the intervention, potentially because average baseline glycemic levels were relatively good. These average values are typical in many systems of care. For example average A1c’s among VA patients nationally are typically less than 7.5%, and a study of six U.S. public hospitals reported that (among patients with an A1c test performed), patients’ median value was 7.6%.53,54 Administrative data from the VA, community-and university systems participating in this study suggest that participants had representative A1c’s compared to the populations from which they were drawn. Despite encouraging trends in physiologic control, a sizable minority of patients with diabetes still have high A1c test results, and future studies should seek to determine whether services such as this can improve glycemic levels among poorly controlled diabetes patients.

Although we assessed patient outcomes at 12 months, the benefits of CBT have been shown to continue for depressive symptoms longer than the benefits of antidepressant medication once treatments are discontinued.21 Longer-term impacts of this intervention on depressive symptoms, physical activity and blood pressure control would be important to determine. Only 16% of participants were racial/ethnic minorities, and generalization to those populations should be done with caution. As with all multi-faceted interventions, it is difficult to parse out the impacts of separate intervention components. Step count increases were statistically significant, but modest in magnitude; further increases in patients’ activity would be desirable. Finally, 31% of patients contacted refused participation, suggesting that a diverse portfolio of programs will be needed to meet all patients’ needs and preferences.

In summary, we found that a targeted program of telephone delivered CBT combined with a pedometer-based walking program significantly decreased patients’ blood pressure, increased physical activity, and decreased depressive symptoms among patients with both diabetes and depression. Health systems seeking to improve mental health and cardiovascular outcomes for these patients should consider using interventions such as this one, which are structured, accessible by telephone, and incorporate pedometer-facilitated walking programs.

Acknowledgments

This NIH-funded trial (1R18DK066166-01A1) is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov and the registration number is NCT01106885.

John W. Williams, M.D. contributed important expert advice during the development of the intervention and the trial design.

Funding Information: This study was supported by NIH grant # 5R18DK66166-3, the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center (NIH #DK020572) and the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (NIH #UL1RR024986). John Piette is a VA Senior Research Career Scientist. At the time of the study, Caroline Richardson was supported by NIH training grant # K23 HL075098. Dana Striplin, M.P.H., managed all data collection and participated in data analysis. Her effort was supported by NIH grant # 5R18DK66166-3.

Footnotes

Results of this study were presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for General Internal Medicine, April 28-May 1, 2010, Minneapolis, MN.

Access Statement

John Piette and Marcia Valenstein had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

No authors have any conflict of interest (financial or material support or assistance) related to this manuscript in any area, including the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, and approval of the final version of the paper.

References

- 1.Ali S, Stone MA, Peters JL, Davies MJ, Khunti K. The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2006;23:1165–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katon WJ. The comorbidity of diabetes mellitus and depression. Am J Med. 2008;121:S8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, de Groot M, Carney RM, Clouse RE. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:934–42. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3278–85. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subramaniam M, Sum CF, Pek E, et al. Comorbid depression and increased health care utilization in individuals with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:220–4. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katon WJ, Rutter C, Simon G, et al. The association of comorbid depression with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2668–72. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kilbourne AM, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Good CB, Sereika SM, Justice AC, Fine MJ. How does depression influence diabetes medication adherence in older patients? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:202–10. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.3.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Delahanty LM, et al. Symptoms of depression prospectively predict poorer self-care in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25:1102–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katon WJ, Russo JE, Heckbert SR, et al. The relationship between changes in depression symptoms and changes in health risk behaviors in patients with diabetes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:466–75. doi: 10.1002/gps.2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson LK, Egede LE, Mueller M, Echols CL, Gebregziabher M. Longitudinal effects of depression on glycemic control in veterans with Type 2 diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:509–14. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Freedland KE, Kissel SS, Clouse RE. Cognitive behavior therapy for depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:613–21. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-8-199810150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lustman PJ, Freedland KE, Griffith LS, Clouse RE. Fluoxetine for depression in diabetes: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:618–23. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.5.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katon W, Russo J, Von Korff M, Lin E, Ludman E, Ciechanowski P. Long-term effects on medical costs of improving depression outcomes in patients with depression and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1155–9. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams JW, Jr, Katon W, Lin EH, et al. The effectiveness of depression care management on diabetes-related outcomes in older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:1015–24. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-12-200406150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, et al. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1042–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ell K, Katon W, Xie B, et al. Collaborative care management of major depression among low-income, predominantly Hispanic subjects with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:706–13. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Nuyen J, Stoop C, et al. Effect of interventions for major depressive disorder and significant depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2010;32:380–95. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katon WJ, Simon G, Russo J, et al. Quality of depression care in a population-based sample of patients with diabetes and major depression. Med Care. 2004;42:1222–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:725–31. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piette JD, Richardson C, Valenstein M. Addressing the needs of patients with multiple chronic illnesses: the case of diabetes and depression. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:41–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K, Swindle R. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for somatization and symptom syndromes: a critical review of controlled clinical trials. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69:205–15. doi: 10.1159/000012395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher L, Mullan JT, Arean P, Glasgow RE, Hessler D, Masharani U. Diabetes distress but not clinical depression or depressive symptoms is associated with glycemic control in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:23–8. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lysy Z, Da Costa D, Dasgupta K. The association of physical activity and depression in Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25:1133–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKercher CM, Schmidt MD, Sanderson KA, Patton GC, Dwyer T, Venn AJ. Physical activity and depression in young adults. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:161–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merom D, Phongsavan P, Wagner R, et al. Promoting walking as an adjunct intervention to group cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders--a pilot group randomized trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:959–68. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suija K, Pechter U, Kalda R, Tahepold H, Maaroos J, Maaroos HI. Physical activity of depressed patients and their motivation to exercise: Nordic Walking in family practice. Int J Rehabil Res. 2009;32:132–8. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e32831e44ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bravata DM, Smith-Spangler C, Sundaram V, et al. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review. Jama. 2007;298:2296–304. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.19.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck A, Ward C, Mendelson M, Mock J, Earbaugh K. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Midanik LT. Perspectives on the validity of self-reported alcohol use. Br J Addict. 1989;84:1419–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Washburn RA, McAuley E, Katula J, Mihalko SL, Boileau RA. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): evidence for validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:643–51. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burns DD. The Feeling Good Handbook. New York, NY: Plume Book; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arsie MP, Marchioro L, Lapolla A, et al. Evaluation of diagnostic reliability of the DCA 2000 for rapid and simple monitoring of HbA1c. Acta Diabetologica. 2000;37:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s005920070028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief cope. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams GC, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1644–51. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.10.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams GC, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: a test of self-determination theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:767–79. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555–67. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American Diabetes Association. Executive Summary: Clinical Practice Recommendations for Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:S4–S10. [Google Scholar]

- 43.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Differences in control of cardiovascular disease and diabetes by race, ethnicity, and education: U.S. trends from 1999 to 2006 and effects of Medicare coverage. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;150:505–15. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-8-200904210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vijan S, Hayward RA. Treatment of hypertension in type 2 diabetes mellitus: blood pressure goals, choice of agents, and setting priorities in diabetes care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:593–602. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-7-200304010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Echeverry D, Duran P, Bonds C, Lee M, Davidson MB. Effect of pharmacological treatment of depression on A1C and quality of life in low-income Hispanics and African Americans with diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2156–60. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayashi T, Tsumura K, Seumatsu C, Okada K, Fujii S, Endo G. Walking to work and the risk for hypertension in men: the Osaka health survey. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:21–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-1-199907060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fagard RH. Effects of exercise, diet, and their combination on blood pressure. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2005;19:S20–S4. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.NIH Science of Behavior Change Meeting Summary. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; Jun 15–16, 2009. http://wwwnianihgov/NR/rdonlyres/AF0997F6-0C16-4A76-96C0-D3780F00E6D4/13545/2009Jun_SOBCMeetingReport_finalpdf. [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Mello MF, Mari JJ, Bacaltchuk J, Verdeli H, Neugebauer R. A systematic review of research findings on the efficacy of interpersonal therapy for depressive disorders. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2005;255:75–82. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0542-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flynn HA. Setting the stage for the integration of motivational interviewing with cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of depression. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2011;18:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duffy SA, Ronis DL, Valenstein M, et al. A tailored smoking, alcohol, and depression intervention for head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2203–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tseng CL, Brimacombe M, Xie M, et al. Seasonal patterns in monthly A1c values. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;161:565–74. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chew LD, Schillinger D, Maynard C, Lessler DS. Glycemic and lipid control among patients with diabetes at six U.S. public hospitals. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2008;19:1060–75. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]