Abstract

Neurofibromatosis type 1 is an autosomal dominant disorder affecting the ras proto-oncogene. It is characterized by the overgrowth of nervous tissue and skin discoloration. While it is associated with a variety of phenotypic presentations, it is the plexiform variant that is particular concerning, as it can become extremely disfiguring and has a propensity for malignant degeneration.

A case of a Pacific Islander with a large plexiform type 1 neurofibroma is presented. The patient was ultimately treated with surgical resection, negative pressure wound therapy, and split-thickness skin grafting with good results. A review of the literature concerning the diagnosis and treatment of neurofibromatosis is included.

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is an autosomal dominant disorder affecting the ras proto-oncogene, resulting in growth of nervous and fibrotic tissues.1 It has a variety of clinical presentations ranging from benign café-au-lait macules to malignant degeneration of plexiform neurofibromas. The hallmark neurofibromas can grow large in size and result in significant disfiguration. Currently, outside of clinical trials, treatment is limited to surgical resection.2

Case Report

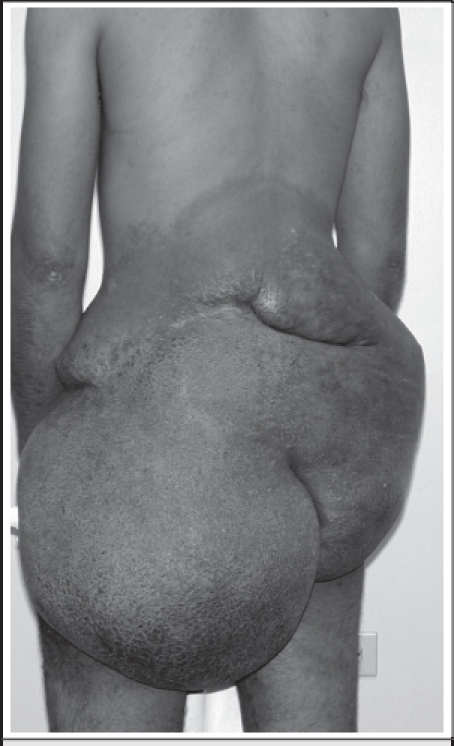

A 19-year-old man was referred to our institution from the Republic of the Marshall Islands via the Pacific Island Health Care Project for evaluation and treatment of a large mass of the back and buttock (Fig. 1).3 The mass had been present since birth and had been progressively enlarging over the past several years. The patient reported embarrassment over the disfigurement caused by the mass.

Figure 1.

Physical examination revealed a soft tissue mass of the back that extended from the tenth thoracic vertebra to the inferior gluteal clefts. The mass had hyperpigmentation, corrugations, and neovascularization. No additional neurofibromas or café-au-lait spots were noted. Neurological examination was normal. CT scan images demonstrated the mass to be confined to the subcutaneous tissues, without extension into the underlying musculature.

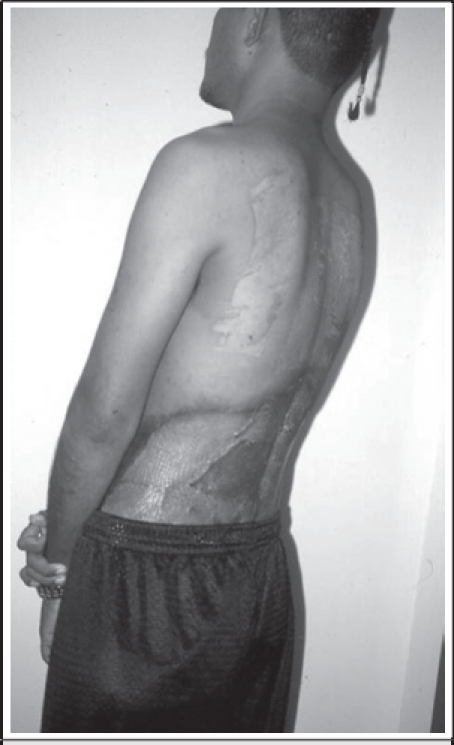

The patient underwent a radical resection of the mass. The superfi cial margins were the tenth thoracic vertebra superiorly, laterally to the anterior abdominal wall, and inferiorly to the gluteal clefts. The deep resection margin was the paravertebral fascia. The wound was initially managed with negative pressure wound therapy, and once a bed of healthy granulation tissue was created, autogenous skin was harvested from the upper back and grafted to the granulation bed. Two weeks later, excellent graft take was noted (Fig. 2) and the patient returned home.

Figure 2.

Discussion

Neurofibromatosis type 1, also known as von Recklinghausen's disease, is an autosomal dominant disease with an incidence of 1 in 2,600 to 3,000 individuals. It has equal distribution between men and women and in one half of patients there is a family history of neurofibromatosis.4,5

The disease results from a mutation of the NF1 gene on chromosome 17q. The gene codes for neurofibromin, a 260 kDa ubiquitously expressed protein found throughout the body.6 The protein has both structural and functional similarity to guanosine triphosphatase - related proteins that are involved in the regulation of the protooncogene ras. Therefore, it has been speculated that the function of the NF-1 gene may be related to its ability to modify ras-mediated cell proliferation.6 Mutations of the gene have highly variable phenotypic expression, resulting in a heterogeneous presentation.7 The hallmark of NF1 is the hyperpigmented cutaneous lesions. Diagnostic criteria were developed by a National Institutes of Health consensus conference in 1987 and refined by a second conference in 1997 (Table 1).8 Few if any patients, however, will manifest all of the clinical features. In fact, for nearly one-third of patients the clinical diagnosis will be made based on a family history and the presence of only one of the six characteristic physical features.8

Table 1.

National Institutes of Health Diagnostic Criteria for Neurofibromatosis Type 1

| Two or more of the following clinical features must be present: |

| Six or more café-au-lait macules (> 5 mm in greatest diameter in prepubertal individuals or > 15 mm in greatest diameter in postpubertal individuals) |

| Two or more neurofibromas of any type or one plexiform neurofibroma |

| Freckling in the axillary or inguinal regions |

| Optic glioma |

| Two or more iris hamartoma (Lisch nodules) |

| Distinctive bony lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia, or thinning of the long bone cortex with or without pseudoarthrosis |

| A first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or offspring) with NF 1 based on the above criteria. |

Various subtypes of neurofibromas have been described based on histologic appearance and location. These include the cutaneous, subcutaneous, nodular, and diffuse plexiform variants.19 The former two arise from the distal end of the nerve and are localized to the cutaneous and subcutaneous skin layers respectively. Nodular neurofibromas arise from the proximal nerve root and are often found growing within organs. Finally, the diffuse plexiform variant involves long segments of multiple nerves. This is in contrast to the other 3 types which rarely if ever involve long segments of the nerve or the axon itself. Additionally, this variant can be found in any histologic layer of tissue where nerves are present.

The plexiform variant of neurofibromatosis represents a major cause of morbidity and disfigurement. Approximately 20–44% of individuals with neurofibromatosis type 1 develop plexiform neurofi bromas.9 Plexiform variants are slow-growing tumors, which may be present at birth or develop later in life. These lesions are composed of an overgrowth of neural elements of tumor and connective tissue that infiltrate normal tissue. They can be superficial (affecting the skin and subcutaneous tissue) or deep (affecting visceral and adjacent tissues through occluding or obstructive mechanisms). They arise in various regions of the body, including the trunk, limbs, head, and neck. In a study of 126 individuals 16 years of age or older with NF1, plexiform neurofibromas were found in the chest of 20% of patients and in the abdomen and pelvis of 44 %.9 This particular variant of neurofibromatosis is especially concerning as it has a 20% risk for malignant degeneration into peripheral nerve sheath tumor.1,10 Furthermore, these spindle cell sarcomas tend to be poorly responsive to therapy, are frequently metastatic at the time of diagnosis, and are associated with a 28% 5-year survival.11

No specific treatment for plexiform neurofibromas currently exists, aside for surgical resection. Clinical trials examining conventional chemotherapeutic agents, antifibrotic agents, and other biologic therapies have had mixed results. Pirfenidone, an antifibrotic agent, has been shown to inhibit survival of human neurofibroma xenografts in mice, but human trials have been less promising.12 In adults, pirfenidone has been shown to decrease the size of the neurofibroma by up to 15% in a minority of patients, however, these results were not sustained at 24 month follow up.13 A phase one trial in pediatric patients had similar disappointing results.14 Thalidomide, a Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha inhibitor, has also been tested with poor results. In a trial of 20 patients, 67% showed no change in tumor size after 1 year of treatment and the remaining patients had a less than 25% reduction in tumor size.15

In light of the poor results from medication trials, primary therapy continues to be complete surgical excision of the neurofibroma. This can be a challenging procedure as the lesion may involve multiple nerve fascicles, with serpiginous growth and significant vascularity.16 Indications for resection of plexiform neurofibromas include cosmesis, intractable pain, neurologic deficit, suspected malignant transformation, and progressive enlargement with compressive effects.17 Even with surgical excision, plexiform neurofibromas have a recurrence rate of 20%.18

In summary, there are several types of neurofibromas including: cutaneous, subcutaneous, nodular, and diffuse plexiform. The cutaneous neurofibromas are benign soft, fleshy lesions that are most concerning for cosmetic reasons. In contrast, subcutaneous neurofibromas are firm and tender lesions that can cause pain and neurological deficits. However, the plexiform variant is the major cause of morbidity and disfigurement. Unlike the other variants, plexiform neurofibromas carry an increase risk of malignant peripheral sheath tumors. These tumors typically arise from preexisting plexiform lesions, metastasize widely, and present with poor outcomes. The treatment for this variant of neurofibromatosis is complete excision of the malignant peripheral sheath tumor with palliative chemotherapy.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the US Government.

References

- 1.Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serletis D, Parkin P, Bouffet E, et al. Massive plexiform neurofibromas in childhood: natural history and management issues. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:363–367. doi: 10.3171/ped.2007.106.5.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Person DA. Pacific Island Health Care Project: Early experiences with a web-based consultation and referral network. Pac Health Dialog. 2000;7:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lammert M, Friedman JM, Kluwe L, Mautner VF. Prevalence of neurofibromatosis 1 in German children at elementary school enrollment. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:71–74. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKeever K, Shepherd CW, Crawford H, Morrison PJ. An epidemiologic, clinical and genetic surgery of Neurofibromatosis type 1 in children under sixteen years of age. Ulster Med J. 2008;77:160–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeClue JE, Papageorge AG, Fletcher JA, et al. Abnormal regulation of mammalian p12ras contributes to malignant tumor growth in von Recklinghausen (type 1) neurofibromatosis. Cell. 1992;69:265–273. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90407-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Easton DF, Ponder MA, Huson SM, Ponder BA. An analysis of variation in expression of neurofibromatosis (NF) type 1 (NF1): evidence for modifying genes. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:305–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeBella K, Szudek J, Friedman JM. Use of the National Institutes of Health Criteria for Diagnosis of Neurofibromatosis 1 in Children. Pediatrics. 2000;105:608–614. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huson SM, Harper PS, Compston DA. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis: a clinical and population study in south-east Wales. Brain. 1988;111:1355–1381. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.6.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korf BR. Malignancy in neurofibromatosis type 1. Oncologist. 2000;5:477–485. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-6-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrari A, Bisogno G, et al. Soft tissue sarcomas in children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis type 1. Cancer. 2007 Apr 1;109(7):1406–1412. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Petrovic L, Knudsen BE, et al. Survival of human neurofibroma in immunodefi cient mice and initial results of therapy with pirfenidone. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2004;2:79–85. doi: 10.1155/S1110724304308107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Ballman K, Michels V, et al. Phase II trial of pirfenidone in adults with neurofi bromatosis type 1. Neurology. 2006;67:1860–1862. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000243231.12248.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Widemann BC, Dombi E, et al. Phase I trial of pirfenidone in children with neurofibromatosis 1 and plexiform neurofibromas. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta A, Cohen BH, Ruggieri P, Packer RJ, Phillips PC. Phase I study of thalidomide for the treatment of plexiform neurofibroma in neurofibromatosis 1. Neurology. 2003;60:130–132. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000042321.94839.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutmann DH. Recent insights into neurofibromatosis type 1: clear genetic progress. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:778–780. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.6.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhattacharyya AK, Perrin R, Guha A. Peripheral nerve tumors: management strategies and molecular insights. J Neurooncol. 2004;69:335–349. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000041891.39474.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Needle MN, Cnaan A, Dattilo J, et al. Prognostic signs in the surgical management of plexiform neurofibroma: the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia experience, 1974–1994. J Pediatr. 1997;131:678–682. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yohay K. Neurofibromatosis Types 1 and 2. Neurologist. 2006;12:86–93. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000195830.22432.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]