Abstract

Gene therapy of muscular dystrophy requires systemic gene delivery to all muscles in the body. Adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors have been shown to lead to body-wide muscle transduction after a single intravascular injection. Proof-of-principle has been demonstrated in mouse models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and limb girdle muscular dystrophy. Before initiating clinical trials, it is important to validate these promising results in large animal models. More than a dozen canine muscular dystrophy models have been developed. Here, we outline a protocol for performing systemic AAV gene transfer in neonatal dogs. Implementing this technique in dystrophic dogs will accelerate translational muscular dystrophy research.

Keywords: AAV: adeno-associated virus, Muscular dystrophy, Alkaline phosphatase, Gene therapy, Dog, Systemic gene transfer

1. Introduction

Gene therapy for muscle diseases faces a unique challenge. Since muscle is widely distributed throughout the body, a successful muscle gene therapy would require body-wide transduction. This barrier was surmounted in rodent models recently (1, 2). By exploring the unique capsid property of different adeno-associated virus (AAV) variants, investigators have achieved robust whole-body transduction in normal and dystrophic rodents with AAV-6, 8, and 9 (1–4). The key issue now is whether a single intravenous AAV injection can transduce whole body muscle in a large animal model and ultimately in human patients.

Exploring systemic gene delivery in large animal models is extremely relevant in muscular dystrophy gene therapy research. The lack of the characteristic dystrophic phenotype has greatly limited translational implication of rodent study results. On the other hand, the canine muscular dystrophy models display the typical clinical manifestations seen in human patients (5). It is expected that the results from studies performed in the dog models may yield a more accurate prediction on the potential outcomes of human trials. Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is by far the most common form of muscular dystrophies. Duchenne-like muscular dystrophy has been observed in more than a dozen canine breeds. Some of these canine models have been fully characterized at the genetic, biochemical, and clinical levels and experimental colonies have been established.

In this protocol, we outline the procedures for performing systemic AAV delivery in neonatal dogs. Traditionally, DMD patients are diagnosed between 2 and 5 years of age, when they cannot reach motor skill milestones (6). At this time, the progression of muscle diseases already results in clinically evident damage. Therapies initiated after this time may have already missed the best window. Affordable chemical and molecular tests have been developed for neonatal DMD diagnosis (7). As a matter of fact, newborn DMD screening has been implemented in many places (8–10). Neonatal gene therapy would offer more to the parents of a newly diagnosed case than the medical, emotional, and reproductive consulting now contemplated. Since DMD is uniformly lethal, the FDA has indicated that it will apply special regulations (FDA regulation Title 21, Chapter I, Subchapter D, Part 312, Subpart E, Sections 312.80–84). In particular, the FDA “takes into consideration the severity of the disease and the absence of satisfactory alternative therapy” and the FDA will “exercise the broadest flexibility in applying the statutory standards.” The lessons learned from neonatal canine gene therapy studies will be important stepping-stones to achieve systemic therapy in symptomatic patients in the future.

Besides detailing the neonatal systemic AAV delivery procedure, we also provide methods on newborn dog generation, muscle biopsy and necropsy, and transduction efficiency evaluation using the heat-resistant human placental alkaline phosphatase (AP) reporter gene.

2. Materials

2.1. Delivering an AAV-9 AP Vector Through the Jugular Vein in Newborn Dogs

Recombinant AAV-9 vector. In this protocol, we describe systemic AAV-9 delivery in newborn dogs using the RSV.AP vector. In this vector, AP gene expression is under the transcription regulation of the ubiquitous Rous sarcoma virus promoter (RSV) and the SV40 polyadenylation signal (see Note 1) (11).

Female dogs (see Note 2).

Semen from normal or affected dogs (see Note 3).

Ultramark 4 plus ultrasound machine (ATL-Philips, Andover, MA, USA) (see Note 4).

Xplorer X-ray machine (Imaging Dynamics Calgary, AB, Canada) (see Note 4).

Vicks digital rectal thermometer (Kaz, Hudson, NY, USA) (see Note 5).

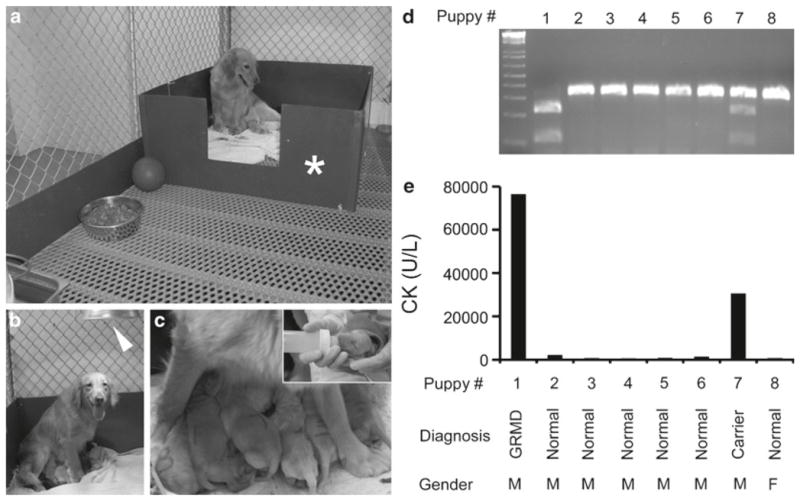

Whelping facility. It includes a whelping box (The Jonart Whelping Box, Ada, MI, USA), white blankets, and an infrared heating lamp (Erin’s Edge Dog Supply, Richfield, WI, USA) (Fig. 1).

Sharpie marker pen (Sanford, Oak Brook, IL, USA).

Braun electric shaver (Procter & Gamble, Cincinnati, OH, USA).

PetAg Esbilac puppy milk replacer (PETCO Animal Supplies, San Diego, CA, USA).

DNA extraction buffer: 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, 0.5 mg/mL proteinase K.

Other reagents for DNA extraction: 6 M NaCl, isopropanol, and 70% ethanol.

Model 5417C Eppendorf centrifuge (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany).

PCR primers for the GRMD genotyping. Forward primer, CTTAAGGAATGATGGGCATGGG; Reverse primer, ATGCATAGTTTCTCTTTCATGC (see Note 6) (Fig. 1) (12).

Green GoTaq Flexi PCR kit (Promega; Madison, WI, USA). The kit contains 5× Green GoTaq Flexi buffer and GoTaq DNA polymerase.

Eppendorf mastercycler personal PCR machine (Eppendorf).

Sau96I restriction enzyme (New England Biolab, Ipswich, MA, USA).

Betadine scrub (SmartPak Equine, Plymouth, MA, USA).

Heparin sodium (1,000 USP units/mL) (Abraxis Pharmaceutical Products, Schaumburg, IL, USA).

A 23G butterfly (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA).

A 10 mL syringe.

0.9% Sodium chloride (Baxter Health Care Corporation, Deerfield, IL, USA).

Surgical supplies including sterilized gauze (Tyco Healthcare; Princeton, NJ, USA), 70% isopropyl rubbing alcohol (Medichoice, Mechanicsville, VA, USA), and sterilized scissors (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA).

Digital postal scale (Harbor Freight, Camarillo, CA, USA).

Thermophore heating pad (Medwing, Columbia, SC, USA).

Fig. 1.

Perinatal care and the GRMD genotyping. (a) Whelping room. Asterisk, whelping box. (b) A carrier dam and her puppies. Arrowhead, infrared heating lamp. (c) Breast feeding. Insert, bottle feeding for affected puppies. (d) Genotyping of a litter by PCR/Sau961 restriction fragment length polymorphism. Wild type allele, 328 bp; GRMD allele, 221 and 107 bp. (e) CK value from the same set of the litter. Puppy #1 is an affected dog. Puppy #7 is a carrier. Remaining puppies are normal dogs.

2.2. Evaluating AP Expression

Preanesthetic cocktail: atropine sulfate (0.04 mg/kg), acepro-mazine maleate (0.02 mg/kg), and butorphanol tartrate (0.4 mg/kg) (IVX Animal Health, St. Joseph, MO, USA).

Anesthetic agents: propofol (up to 3 mg/kg) (IVX Animal Health), isoflurane (Halocarbon, River Edge, NJ, USA).

Veterinary anesthesia machine with ventilator and vaporizer (KEEBOSHOP, Chicago, USA).

20–22G IV catheter (Becton-Dickinson Medical Supply, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Lactated Ringer’s solution (Valley Vet Supply, Marysville, KS, USA).

4% Chlorhexidine scrub (First Priority, Elgin, IL, USA).

Cephazolin, a generic antibiotic drug.

Muscle biopsy instruments: Sterile forceps and scissors (World Precision Instruments), sterile needle holders (Accurate Surgical & Scientific Instruments Corp., Westbury, NY, USA). #10 Bard-Parker stainless steel surgical blades (Becton-Dickinson Medical Supply). 4-0 Vicryl suture and 4-0 Ethilon suture (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA).

Carprofen (VÉTOQUINOL USA, Fort Worth, TX, USA).

Euthasol solution CIII (Virbac, Fort Worth, TX, USA): a veterinary euthanasia solution containing pentobarbital sodium and phenytoin sodium.

Stethoscope.

TBJ necropsy table (LABES of MA, Worcester, MA, USA).

Muscle necropsy instruments: Curved and straight scissors, tissue forceps, and hemostats (Biomedical Research Instruments, Silver Spring, MD, USA); tissue trimming knives and blades (Baxter Scientific, Columbia, MD, USA); 6 in. necropsy knife, rongeurs, bone cutting shears, scalpel blades, and handles (National Logistics Services, Westfield, MA, USA); heavy bone chisel, Virchow’s skull breaker, bone cutting saw, poly-ethylene dissecting boards (Thermo Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

2-Methylbutane.

Liquid nitrogen.

Tissue-Tek OCT (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA, USA).

Microm HM505 EVP cryostat (Richard Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI, USA).

0.5% Glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

PBS containing 1 mM MgCl2.

AP prestaining buffer: 100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 9.5, 50 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl.

AP staining solution: 165 μg/mL 5′-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate-p-toluidine (stock as 50 mg/mL in 100% dimethyformamide), 330 μg/mL nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (stock as 75 mg/mL in 70% dimethyformamide), 50 μM levamisol (13). Prepare at the time of use.

Monoclonal antibody for AP (1:8,000; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Alex 594-conjugated rabbit antimouse antibody (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA).

Thermo Aqua-mount (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

StemTAG AP activity assay kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA). The kit includes the StemTAG AP activity assay substrate, cell lysis buffer, 10× stop solution, and the AP activity assay standard.

Porcelain mortar and pestle.

Model 5417C Eppendorf centrifuge (Eppendorf).

Bio-Rad protein concentration assay kit (Bio-Rad, Heracules, CA, USA).

3. Methods

3.1. Delivering an AAV-9 AP Vector Through the Jugular Vein in Newborn Dogs

Dog breeding. Deliver the semen to the uterus of a bitch twice at 48 and 72 h postovulation by artificial insemination (see Notes 2 and 3). Record the body weight weekly. One month postartificial insemination, confirm the pregnancy with ultrasound. Count the number of fetus by X-ray at the 60th day of gestation (see Note 4).

Puppy delivery. Record the body temperature of the bitch three times a day starting from the 58th day of pregnancy. Prepare for labor and delivery when temperature drops below 99°C and keeps dropping (see Note 5).

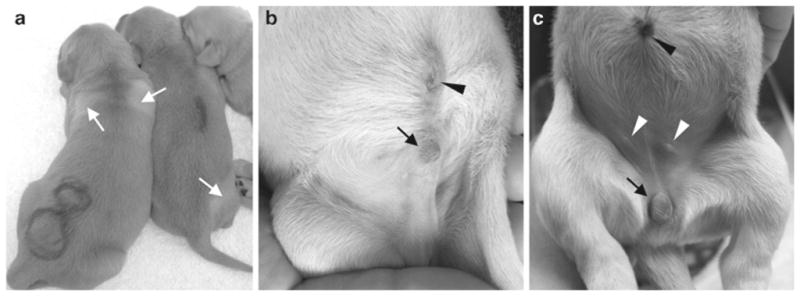

Record the birth time, body weight, hair color, and gender of each puppy (Fig. 2). Write the birth order on the back of the puppy with a marker pen. Shave ~1 cm2 of the hair at the defined locations (such as the left shoulder, the right hip, etc.) as an additional marker (Fig. 2). For each puppy, crop a 0.5-in. long cord with a pair of sterile scissors. Place the puppy next to one of the nipples to allow it start nursing. Record the total number of puppies and placentas delivered. Make sure every puppy gets some colostrum (the milk from the dam in the first 24 h). Draw blood from the jugular vein and measure the serum creatine kinase level and liver function. Consult a veterinary doctor immediately in the case of difficult labor. Carefully monitor the general health of the dam and puppies. Record the body weight of newborn puppies three times a day in the first 2 weeks and then twice a day in weeks 3 and 4. Start supplementing with the Esbilac puppy formula if the puppy is weak or does not nurse well (see Note 7).

Mince the cord with a razor blade. Add 750 μL DNA extraction buffer. Incubate at 55°C overnight on a spinning wheel. Add 250 μL 6 M NaCl. Incubate at room temperature for 1 h on a spinning wheel. Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 30 min. Transfer the supernatant to a new tube. Add 600 μL isopropanol. Mix for 5 min by shaking. Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 2 min. Wash the pellet with 70% ethanol. Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 2 min. Air dry the pellet for 1 h. Resuspend the pellet in 50 μL PCR-quality water as the cord genomic DNA. Mix 0.5 μL cord DNA, 4 μL of 5× green GoTaq Flexi buffer, 1.6 μL of 10 mM dNTP, L of 25 mM MgCl2, 0.4 μ 0.5 μL of each primer (20 μM stock), 0.1 μL of GoTaq DNA polymerase, and 12.9 μL PCR-quality water. Start PCR with initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min. Continue PCR with 35 cycles of 95°C 20 s denaturation, 58°C 20 s annealing, and 72°C 20 s extension. Digest 10 μL PCR product with 2 units of Sau96I at 37°C for 2 h. Examine in 2% agarose gel. Wild type allele yields a 328 bp band. Affected allele yields two bands at 221 and 107 bp (see Note 8) (Fig. 1).

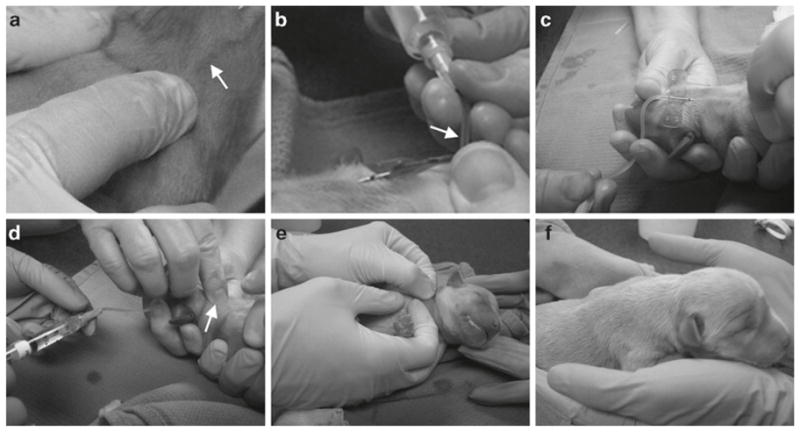

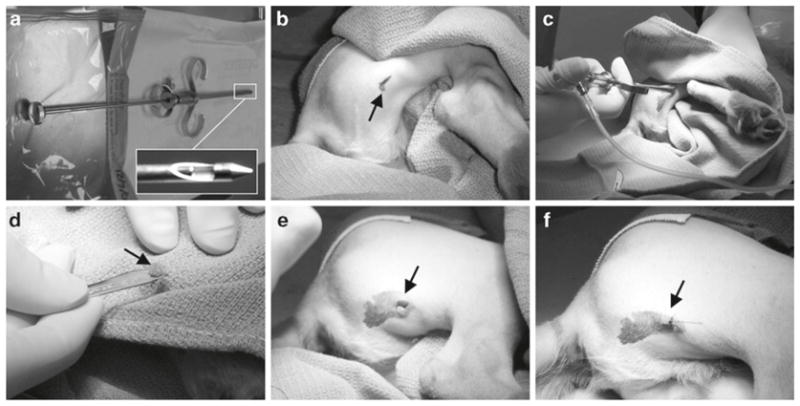

Perform systemic AAV-9 delivery at 24–48 h after birth in conscious puppies. Calculate AAV-9 vector volume based on the body weight at the time of injection. A normal newborn puppy may tolerate up to 25 μL/g body weight (2.5 × 1011 vector genome particles/gram body weight) of AAV-9 vector. Prefill a 23G butterfly with heparinized saline and then connect the butterfly to a 10 mL syringe containing the appropriate volume of AAV. One investigator should restrain the fore limbs and the head of the puppy with hands. Clean the neck skin with the Betadine scrub. Insertion of the butterfly to the jugular vein should be done by another investigator. Gently pull the plunge back and visualize the flashback of blood to confirm if the butterfly is correctly placed inside vein. Infuse AAV to the puppy at the speed of ~5 mL/min. Flush the butterfly with heparinized saline to deliver remaining AAV that is trapped in the connecting tubing. Press the needle entry site with a finger and at the same time retract the butterfly from the jugular vein. Continuously press the needle injection site to stop bleeding. Place the puppy on the heating pad to let it recover (see Note 9) (Fig. 3).

Carefully monitor the vital sign, general response, nursing, and body weight of AAV injected puppies. If they become sluggish, not gaining weight, dehydrated, or not nursing well, consult the veterinary doctor immediately (see Note 10).

Fig. 2.

Neonatal puppy images. (a) Newborn puppy identification. Arrows, areas in which body hair is shaved. (b) A newborn male puppy. Arrow, the male external genital; arrowhead, the umbilicus. (c) A newborn female puppy. Arrow, the female external genital; black arrowhead, the umbilicus; white arrowheads, nipple.

Fig. 3.

The procedure for delivering AAV into a newborn puppy. (a) Reveal jugular vein by applying pressure on the clavicle bone. Arrow, jugular vein. (b) Confirm the correct position of the butterfly inside the jugular vein. Arrow, the flash back of blood. (c) AAV delivery. (d) Flush in AAV vectors inside the tubing and retrieve the butterfly while applying pressure on the needle penetration site. Arrow, needle penetration site. (e) Continuously apply pressure to the injection site to stop bleeding. (f) Puppy recovered after systemic AAV injection.

3.2. Evaluating AP Expression

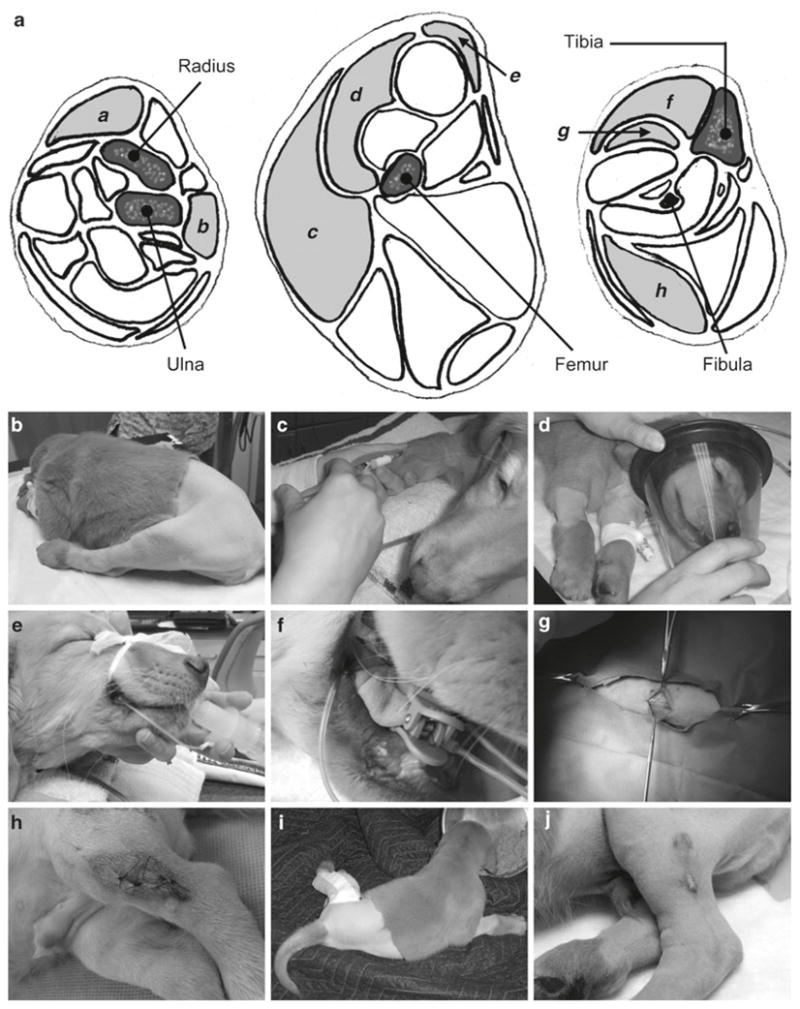

Muscle biopsy. Withhold food for 12 h. Administer the preanesthetic drug cocktail via intramuscular injection. Ten minutes later, administer propofol via a bolus intravenous injection at the dose of 1.5 mg/kg. Administer additional propofol if needed (up to 3 mg/kg). Maintain anesthesia status with 2–3% of isoflurane. Place a 20–22G IV catheter to one of the major veins (such as the jugular, cephalic, femoral, or saphenous vein). Maintain on lactated Ringer’s solution at a flow rate of 50 mL/kg/day for the duration of the procedure. Shave the body hair and scrub at least three times each with 4% chlorhexidine scrub and 70% ethanol before draping the incision site for aseptic surgery. Administer prophylactic antibiotic cephazolin at 22 mg/kg via IV catheter. Make a skin incision over the surface of the target muscle. Gently separate fat and connective tissues to reveal the target muscle. Remove a block of 1 × 0.5 × 0.5 cm muscle tissue with a surgical blade. Close the fascial layer with continuous stitch using absorbable 4-0 Vicryl suture. Close the skin with interrupted stitches using nonabsorbable 4-0 Ethilon suture. Administer carprofen twice a day at the dosage of 2.2 mg/kg for the first 24 h postsurgery to reduce postoperative pain. Provide dog with soft food after surgery. Monitor skin incision daily until it is completely healed (see Note 11) (Fig. 4).

Dog necropsy. Record experimental information (such as dog name, body weight, gender, project title, etc.). Collect the serum from the jugular vein. Euthanize the dog with intravenous injection of Euthasol solution at the dose of 2 mL for the first 10 lb of the body weight and 1 mL per 10 lb for the remaining body weight. Confirm the death by cardiac auscultation with a stethoscope. Cut open the jugular vein to drain blood. Identify each skeletal muscle according to canine anatomy books (14–18). Harvest major body muscles and the internal organs (see Note 12).

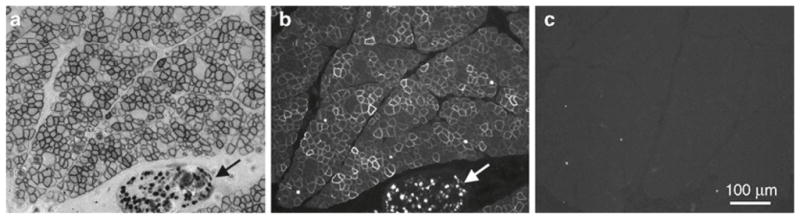

Histochemical staining to evaluate AP expression. Embed the muscle sample in OCT and snap freeze the sample in liquid nitrogen-cooled 2-methylbutane (−155°C). Cut the muscle tissue block into 8 μm sections with a cryostat. Fix muscle sections in 0.5% glutaraldehyde for 10 min. Wash slides with 1 mM MgCl2. Incubate at 65°C for 45 min. Wash with the AP prestaining buffer twice, 5 min each. Stain in the freshly prepared AP staining solution for 5–20 min (see Note 13) (Fig. 5).

Whole mount muscle AP histochemical staining. Cut the muscle to a thickness of ~0.2 in. and a size of ~1 × 1 in. Fix the muscle piece in 0.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h at room tem- for 30 min at room perature. Incubate with 1 mM MgCl2 temperature. Incubate at 65°C for 1.5 h to inactivate endogenous AP. Incubate with two exchanges of the AP prestaining buffer, 30 min each. Stain in freshly prepared AP staining solution for 60 min at 37°C (19).

Immunofluorescence staining for AP. Air dry 8 μm muscle cryosections. Wash with PBS for 5 min. Block with 20% rabbit serum at room temperature for 30 min. Wash with PBS twice, 5 min each. Incubate with the monoclonal AP antibody (1:8,000, diluted in 1% rabbit serum/PBS) at 4°C overnight. Wash with 1% rabbit serum/PBS three times, 5 min each. Incubate with the Alex 594-conjugated rabbit antimouse antibody (1:100, diluted in 1% rabbit serum/ PBS). Wash with 1% rabbit serum/PBS three times, 5 min each. Coverslide with a drop of Aqua-mount (Fig. 5) (19).

Quantifying AP expression in muscle lysate. Pulverize ~100 mg muscle tissue in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and a pestle. Resuspend the muse powder in 700 μL of cell lysis buffer. Incubate the crude lysate at 65°C for 60 min. Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 1 min. Save the supernatant as muscle lysate. Measure the protein concentration with the Bio-Rad protein concentration assay kit. Add 5 μL muscle lysate to 50 μL StemTAG AP activity assay substrate. In another tube, add 5 μL cell lysis buffer to 50 μL StemTAG AP activity assay substrate. (This will be used as the blank for OD measurement.) Incubate at 37°C for 30 min. Add 50 μL 1× stop solution. Measure OD at 405 nm. Calculate raw AP activity using the formula of (OD 405 value × 20)/protein concentration (in μg/μL). Plot the raw AP activity value on the AP activity standard curve to get actual AP activity value (μM/μg) (see Note 14) (3, 19, 20).

Fig. 4.

Surgical muscle biopsy. (a) Schematic drawings of the lower forelimb (left), thigh (middle), and lower hind limb (right). Muscles commonly used for surgical biopsy are marked with small letters. a extensor carpi radialis; b extensor carpi ulnaris; c biceps femoris; d vastus laterialis; e cranial sartorius; f cranial tibialis; g long digital extensor; h the lateral head of gastrocnemius. (b) Prepare the skin for muscle biopsy and establish the intravenous route. (c) Inject preanesthetic drug cocktail. (d) Anesthetize the dog with isoflurane. (e) Intubate the trachea. (f) Clip the oximeter sensor to the tongue. (g) Make skin incision. (h) Suture the skin after removing the muscle. (i) Recover normal feeding after surgery. (j) Suture wound heal at 3 weeks postsurgery.

Fig. 5.

Detect AP expression on muscle sections. A golden retriever dog was infected with AAV-9 AV.RSV.AP at 48 h of age and AP expression was examined at 6 months of the age. Representative images from serial sections of the cranial sartorius muscle. (a) AP histochemical staining. (b) AP immunofluorescence staining. (c) Immunofluorescence staining with the secondary antibody. Arrow, nerve.

Fig. 6.

Needle muscle biopsy. (a) Biopsy needle. The insert shows a close view of the tip of the needle. (b) Skin incision. (c) Needle inside the muscle. (d) Muscle sample obtained from needle biopsy (arrow). (e) Skin wound after biopsy. (f) Skin is sutured with a single stitch.

Acknowledgments

The protocols were developed with the grant support from the National Institutes of Health (HL-91883, AR-49419 and AR-57209 to DD) and the Muscular Dystrophy Association (DD). We thank Drs. Dietrich Volkmann, Bruce Smith and Joe Kornegay for helpful discussion. We thank Robert J. McDonald, Jr., M.D. for the generous support to Duchenne muscular dystrophy research in the Duan lab.

Footnotes

AAV-9 vector used in our study is purified through three rounds of isopycnic CsCl ultracentrifugation and dialyzed through three changes of HEPES buffer. AAV-9 vectors can also be purchased from the Penn Vector at the University of Pennsylvania Gene Therapy Program (Philadelphia, PA) or the Powell Gene Therapy Center at the University of Florida (Gainesville, FL). It is crucial to check the endotoxin levels of the AAV stocks. We usually use the EndoSafe LAL gel clot test kit (Charles Rivers Laboratory, Wilmington, MA, USA). In general, the endotoxin level should be less than 5 EU/kg. We strongly recommend confirm AAV vector activity in murine models prior to the use for systemic gene delivery in dogs. We would like to point out that while the human placental AP protein is heat-resistant, the canine placental AP protein is heat-labile (21, 22). Besides the AP reporter gene, investigators may also use AAV vectors carrying other reporter genes such as the luciferase gene, the LacZ gene, the ntLacZ gene, or the GFP gene. The differences in the subcellular expression pattern and the assay sensitivity should be considered for data interpretation. The AP protein preferentially localizes at the cell membrane while the ntLacZ protein expresses in the nucleus. For reporter gene study, a ubiquitous promoter (such as the RSV, CMV, CB and CAG) is preferred since it provides information on AAV transduction in nonmuscle tissues. However, for gene therapy in a dystrophic canine model, a muscle specific promoter would be preferred.

A female dog usually starts her first heat cycle between the ages of 6–12 months. Most female dogs have their cycle every 6–8 months. When a bitch is in heat, one will notice an increase of urination, swelling of the vulva, and bloody discharge from the vagina. The heat period usually lasts ~20 days. The best time to breed is 48–72 h postovulation. Ovulation usually occurs at ~14 days after the bitch is in heat. A better way to determine the prime breeding time is by monitoring the progesterone level. Ovulation occurs at the progesterone level of 5 ng/mL.

We recommend artificial insemination rather than natural breeding. The fresh semen is preferred. However, the frozen semen can also be used. When the bitch is not ready, the semen may either be chilled or frozen. Chilled semen should be used within 24 h. It is important to check the quality of the semen before the use.

The gestation period for dogs is usually 62–64 days. The pregnancy can be confirmed at ~28 days into gestation with ultrasound detection of fetal heartbeats. X-rays can be taken around the 60th day of pregnancy to confirm a pregnancy and count the number of fetuses. The whelping date can also be predicted based on vaginal smears. It is usually 57 ± 1 days after the first day of the diestrus.

The normal dog body temperature is around 99–101°C. When it drops below 99°C and continues to drop, labor will start within 12–24 h. When it drops to 98°C, labor will occur within 2–12 h.

The reverse primer is located at the dystrophin gene intron 7. According to the NCBI sequence database (NC_006621), the underlined nucleotide should be a thymidine. According to Bartlett et al., the underlined nucleotide should be an adenine. In our primer, we used thymidine instead of adenine (12).

One can also use color nail polish to paint different claws to mark the puppy. When cutting the cord, make sure to get it from the baby side, not from the placenta side. We suggest use a different pair of sterilized scissors for each puppy. For each puppy, there should be a placenta. The placenta may not come out at the time the puppy is born. If it is retained, the dam will be at the risk of serious uterine infection. It is possible that the number of puppies delivered is different from that predicted by X-ray examination. The signs of difficult labor may include more than half hours of strong contractions without delivering a puppy, more than 4–6 h between two puppies, fail to deliver within 24 h after the temperature drops below 99°C. Colostrum is highly enriched with antibodies, vitamins electrolytes, and other nutrients. If you have a small litter, you may want to freeze some colostrum for future use.

As an example, here we described the PCR protocol for the GRMD genotyping. Based on the dystrophic model you are working with, relevant genotyping assays should be performed. We have found that sometimes the serum CK level may yield an inaccurate diagnosis.

The systemic AAV-9 delivery procedure described here has been successfully used in dogs of different body size (such as the large size golden retriever and small size corgi) and in both normal and affected dogs. We have not seen a significant body weight difference between normal and affected puppies at birth. For this reason, we have applied the exactly same technique for all newborn puppies irrespective of the disease status. Although it is easy to monitor expression in nonmuscle tissues with a reporter gene vector, we recommend the use of a therapeutic vector in the case of affected puppies. To help visualize the jugular vein, one may need to place the thumb at the clavicle bone to stop the returning blood (Fig. 3a). The AAV injected puppy usually recovers within 2 min. If there is volume overload, it may lead to lung edema (coughing and increased lung sound on auscultation). If there is an anaphylactic reaction, the puppy will show hives or collapse. It is important to keep the puppy warm and hydrated.

We have experienced an adverse reaction in a puppy that received AAV-9 injection (25 μL/g body weight, 2.5 × 1011 vector genome particles/gram body weight) at 24 h after birth. The puppy became lethargic and less responsive after AAV injection. Laboratory test at 36 h post-AAV injection showed an increase in several parameters including white blood cell count (2.22 × 104/μL; normal, <1.7 × 104/μL), mean corpuscular volume (84 fl; normal, <77 fl), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (29.7 pg; normal <24.5 pg), banded neutrophil (1.11 × 104/μL; normal, <0.3 × 104/μL), monocyte (6.22 × 104/μL; normal, <1.35 × 104/μL), glucose (154 mg/dL; normal <128 mg/dL), potassium (5.1 mM; normal <4.9 mM), anion gap (23 mM; normal <15 mM), and phosphorus (9 mg/dL; normal <5.9 mg/dL). This puppy recovered after supplementary bottle feeding and subcutaneous injection of lactated Ringer’s solution.

For preweaning puppies, we suggest withhold nursing for 4 h instead of 12 h. During biopsy, we constantly monitor the dog conditions with a veterinary pulse oximeter (Nonin Medical, Plymouth, MN, USA) and a veterinary ECG unit. The first muscle biopsy can be performed as early as 2 weeks post-AAV injection by experienced investigators. Additional biopsy can be performed at 1, 2, 3 months of age prior to necropsy at 6 months of age. If long-term study (>6 months) is planned, additional biopsy can be performed per experimental needs. We have performed muscle biopsy in many different muscles including the extensor carpi radialis, extensor carpi ulnaris, biceps femoris, vastus laterialis, cranial sartorius, cranial tibialis, long digital extensor, and the lateral head of the gastrocnemius (Fig. 4). In the canine model of DMD, the cranial sartorius is one of the most severely affected muscles (23–25). This muscle is also efficiently transduced by AAV-9 (19). We suggest perform biopsy in the cranial sartorius muscle when testing therapeutic gene therapy in the canine DMD models. Mild swelling and temporary discomfort associated with the surgery may be anticipated. Needle biopsy is another commonly used method (Fig. 6). Although needle biopsy is less invasive, the amount of tissue obtained is smaller and the quality could be less ideal than what one gets from surgical biopsy. A special muscle biopsy needle is required (UCH Skeletal Muscle Biopsy Needle; Cadence Science, Lake Success, NY, USA) (Fig. 6a).

A comprehensive whole body necropsy is necessary to fully evaluate systemic gene transfer. We examine skeletal muscle transduction in selected limb, respiratory, and several other body muscles. For limb muscles, both sides are examined. For each limb muscle, collect three samples from the proximal end, middle belly, and the distal end. Following skeletal muscles are harvested including five muscles in the upper forelimb (the long, accessory, medial and lateral heads of the triceps brachii and biceps brachii muscles), four muscles in the lower forelimb (the extensor carpi radialis, extensor carpi ulnaris, flexor carpi ulnaris and superficial digital flexor muscles), nine muscles in the thigh (the vastus laterialis, vastus intermediates, rectus femoris, biceps femoris, cranial and caudal sartorius, semimembranous, semitendinous and adductor muscles), four muscles in the lower hind limb (the cranial tibialis, long digital extensor and the medial and lateral heads of the gastrocnemius muscles), five head muscles (the occipitalis, fron-toscutularis, long auricle levator and temporalis muscles and the tongue), four neck muscles (the sternohyoideus, sterno-cephalideus, cleidocervicalis and trapezius muscles), four chest muscles (the superficial and deep pectoral muscles, the external and internal intercostal muscles), the diaphragm (including eight samples from peripheral and central parts on the anterior, posterior, left and right sides, respectively), two back muscles (the supra and infra spinatus muscles), four abdominal muscles (the rectus, external oblique, internal oblique and transverses muscles), the gluteus muscle, and the latissimus dorsi muscle. These represent muscles at different anatomic positions in the body. They include both superficial (e.g., the biceps femoris muscle) and deep muscles (e.g., the adductor muscle). They also include muscles with different fiber type compositions. For example, the extensor carpi radialis muscle contains 0–45% type I fiber, the cranial sartorius muscle contains 46–75% type I fiber, and the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle contains 76–100% type I fiber (14). In the case of GRMD, these include muscles that are severely affected (e.g., the rectus femoris, cranial sartorius, cranial tibialis, temporalis, trapezius muscles, the tongue and the diaphragm), moderately affected (e.g., the triceps brachii, biceps brachii, extensor carpi radialis, gastrocnemius muscles), and lightly affected (e.g., the biceps femoris muscle) (23–25). Besides skeletal muscle, we also collect representative tissue samples from the heart (five locations including the left and right ventricles, left and right atriums and intraventricular septum), smooth muscles (six locations including the aorta, vena cava, stomach, small and large intestine and bladder) and other internal organs including the brain, retina, lung, liver, spleen, pancreas, kidney, and ovary/testis.

Alkaline phosphatases (EC 3.1.3.1) (APs) are dimeric enzymes. Four different APs have been identified in humans including a nonspecific AP and three tissue-specific isozymes (intestinal AP, germ cell AP and placental AP). Only human placental AP is heat resistant. Crystal structure of human placental AP structure has been resolved at the 1.8 Å resolution (26). Comparative studies suggest that human placental AP gene may yield much stronger expression signal than that of LacZ (27, 28). AP positive cells are shaded in purple/blue color. In muscle, AP expression is usually first detected at the sarcolemma and staining at the sarcolemma usually is much stronger than that in the cytosol. When expression level is low, it may only show up at the sarcolemma. The intensity of histochemical AP staining depends on expression levels. We usually determine the optimal staining time for each study by a pilot experiment. Always include muscle sections from an uninfected dog as negative controls. For muscle sections of the same project, all staining should be performed under the exactly same condition.

If the OD reading is higher than 2.0, dilute muscle lysate with water and repeat the assay. Ideally, the OD reading should be in the range of 0.1–2.0. For tissues from an internal organ (such as the lung, liver and kidney), the crude lysate can also be prepared using a tissue tearor. The AP activity standard curve can be obtained with twofold dilution of the AP activity assay standard provided in the kit.

References

- 1.Wang Z, Zhu T, Qiao C, Zhou L, Wang B, Zhang J, Chen C, Li J, Xiao X. Adeno-associated virus serotype 8 efficiently delivers genes to muscle and heart. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:321–328. doi: 10.1038/nbt1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregorevic P, Blankinship MJ, Allen JM, Crawford RW, Meuse L, Miller DG, Russell DW, Chamberlain JS. Systemic delivery of genes to striated muscles using adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat Med. 2004;10:828–834. doi: 10.1038/nm1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh A, Yue Y, Long C, Bostick B, Duan D. Efficient whole-body transduction with trans-splicing adeno-associated viral vectors. Mol Ther. 2007;15:750–755. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pacak CA, Mah CS, Thattaliyath BD, Conlon TJ, Lewis MA, Cloutier DE, Zolotukhin I, Tarantal AF, Byrne BJ. Recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 9 leads to preferential cardiac transduction in vivo. Circ Res. 2006;99:e3–e9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237661.18885.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shelton GD, Engvall E. Canine and feline models of human inherited muscle diseases. Neuromuscul Disord. 2005;15:127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emery AEH, Muntoni F. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flanigan KM, von Niederhausern A, Dunn DM, Alder J, Mendell JR, Weiss RB. Rapid direct sequence analysis of the dystrophin gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:931–939. doi: 10.1086/374176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley DM, Parsons EP, Clarke AJ. Experience with screening newborns for Duchenne muscular dystrophy in Wales. BMJ. 1993;306:357–360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6874.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drousiotou A, Ioannou P, Georgiou T, Mavrikiou E, Christopoulos G, Kyriakides T, Voyasianos M, Argyriou A, Middleton L. Neonatal screening for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a novel semiquantitative application of the bioluminescence test for creatine kinase in a pilot national program in Cyprus. Genet Test. 1998;2:55–60. doi: 10.1089/gte.1998.2.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parsons EP, Clarke AJ, Hood K, Lycett E, Bradley DM. Newborn screening for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a psychosocial study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;86:F91–F95. doi: 10.1136/fn.86.2.F91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duan D, Yue Y, Yan Z, Yang J, Engelhardt JF. Endosomal processing limits gene transfer to polarized airway epithelia by adeno-associated virus. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1573–1587. doi: 10.1172/JCI8317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartlett RJ, Winand NJ, Secore SL, Singer JT, Fletcher S, Wilton S, Bogan DJ, Metcalf-Bogan JR, Bartlett WT, Howell JM, Cooper BJ, Kornegay JN. Mutation segregation and rapid carrier detection of X-linked muscular dystrophy in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1996;57:650–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Belle H. Alkaline phosphatase. I. Kinetics and inhibition by levamisole of purified isoenzymes from humans. Clin Chem. 1976;22:972–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller ME, Evans HE. Miller’s anatomy of the dog. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goody PC. Dog anatomy : a pictorial approach to canine structure. J.A. Allen; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Budras K-D, McCarthy PH, Fricke W, Richter R. Anatomy of the dog: an illustrated text. Schlèutersche; Hannover: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kainer RA, McCracken T. Dog anatomy: a coloring atlas. Teton NewMedia, Jackson; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans HE, DeLahunta A. Guide to the dissection of the dog. Saunders; St. Louis: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yue Y, Ghosh A, Long C, Bostick B, Smith BF, Kornegay JN, Duan D. A single intravenous injection of adeno-associated virus serotype-9 leads to whole body skeletal muscle transduction in dogs. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1944–1952. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bostick B, Ghosh A, Yue Y, Long C, Duan D. Systemic AAV-9 transduction in mice is influenced by animal age but not by the route of administration. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1605–1609. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldstein DJ, Rogers C, Harris H. Evolution of alkaline phosphatases in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:879–883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.3.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moak G, Harris H. Lack of homology between dog and human placental alkaline phosphatases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:1948–1951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kornegay JN, Cundiff DD, Bogan DJ, Bogan JR, Okamura CS. The cranial sartorius muscle undergoes true hypertrophy in dogs with golden retriever muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2003;13:493–500. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(03)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valentine BA, Cooper BJ. Canine X-linked muscular dystrophy: selective involvement of muscles in neonatal dogs. Neuromuscul Disord. 1991;1:31–38. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(91)90040-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen F, Cherel Y, Guigand L, Goubault-Leroux I, Wyers M. Muscle lesions associated with dystrophin deficiency in neonatal golden retriever puppies. J Comp Pathol. 2002;126:100–108. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.2001.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Du MH, Stigbrand T, Taussig MJ, Menez A, Stura EA. Crystal structure of alkaline phosphatase from human placenta at 1.8 A resolution. Implication for a substrate specificity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9158–9165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell P, Limberis M, Gao G, Wu D, Bove MS, Sanmiguel JC, Wilson JM. An optimized protocol for detection of E. coli beta-galactosidase in lung tissue following gene transfer. Histochem Cell Biol. 2005;124:77–85. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0793-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Z, Yue Y, Lai Y, Ye C, Qiu J, Pintel DJ, Duan D. Trans-splicing adeno-associated viral vector-mediated gene therapy is limited by the accumulation of spliced mRNA but not by dual vector coinfection efficiency. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:896–905. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]