Abstract

The aim of this study was to carry out pharmacological screening in order to evaluate the potential effects of lyophilized fruits of different cultivars of Vaccinium ashei Reade (Family Ericaceae) berries, commonly known as rabbiteye blueberries, on nociception. This was achieved using the formalin, hot plate, tail-flick, and writhing tests in mice. During this experiment the mice consumed approximately 3.2–6.4 mg/kg/day (p.o.) of the anthocyanins. The extract was administered for 21 days or 60 minutes before test. Morphine and diclofenac (10 mg/kg, p.o.) as the standard drug (positive control) and water (via oral gavage) as the negative control were administered before all tests. The blueberry extract produced a significant decrease in constrictions induced by acetic acid and caused graded inhibition of the second phase of formalin-induced pain. Moreover, in both the hot plate and tail-flick tests, it significantly increased the threshold. These data suggest that the extract from V. ashei produced antinociceptive effects, as demonstrated in the experimental models of nociception in mice. Additional experiments are necessary in order to clarify the true target for the antinociceptive effects of rabbiteye blueberry extract.

KEY WORDS: anthocyanins, blueberry, mice, pain, polyphenols

Introduction

Epidemiological reports have revealed the important role that plant-originated foodstuffs play on the prevention of many illnesses. The natural antioxidants present in such foodstuffs, among which polyphenols are widely present, may be responsible for this effect.1 Blueberries are an important dietary source of polyphenols, especially anthocyanins and caffeic acid, as well as its derivatives, which are present in blueberries at relatively high concentrations.2

Anthocyanins, a flavonoid subclass, are predominantly associated with red berries but have also been found in vegetables, roots, and legumes. Because of scientific research they have become not only food ingredients but also therapeutic agents.3 These compounds have been known to be effective analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents in animals, causing a significant reduction in acetic acid-induced writhing responses and carrageenan-induced paw edema.4,5 Similarly, investigations demonstrated a positive effect of proanthocyanins in patients with pancreatitis, slowing down pathologic changes of the organ and alleviating clinical symptoms such as abdominal pain and vomiting.6 Aglycone cyanidin showed better anti-inflammatory activity than aspirin when used an in vitro model that monitors the ability to inhibit cyclooxygenase conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins.7,8 This compound also exhibited inhibitory activity comparable to the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, naproxen and ibuprofen.8,9 Other flavonols found in berries, such as quercitrin, quercetin, hyperoside, and isoquercetrin, have been shown to inhibit cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase activities; both enzymes are involved in the release of arachidonic acid, the initiator of general inflammatory responses.10,11

In view of the reputed efficacies of these phenolic compounds, in this article we describe a study in which the antinociceptive action of polyphenolic extracts of Vaccinium ashei Reade (Family Ericaceae) berries was assayed through different nociceptive chemical and thermal experimental models in mice. Additional experiments were conducted in order to determine the phytochemical profile of V. ashei, through high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with photodiode array detection.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Swiss albino mice (weighing 25–30 g) from the Animal House of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande (Rio Grande, RS, Brazil) were used in the present investigation. Animals were housed in temperature-controlled rooms (20–22°C), under a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 0700 h) and 55 ± 1% relative humidity. Standard rodent diet and tap water were provided ad libitum. Experiments were performed after protocol approval by the Institutional Ethics Committee (protocol number 113/2005-03 CEP-UNIVALI) and were carried out according to the current guidelines for laboratory animal care and ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals.12 The number of animals (10 per group) and intensity of noxious stimuli used were the minimum necessary for demonstrating the consistent effects of the drug treatments. Each animal was used only once (with the exception of the hot plate test) and was afterwards sacrificed by exposure to CO2.

V. ashei cultivars

Representative samples of V. ashei Reade berries were collected at random from the following cultivars: Woodard, Delite, Climax, Briteblue, Bluegen, Bluebelle, Aliceblue, and Florida (all originally American). Plants were produced by EMBRAPA (Pelotas, RS, Brazil) and maintained at 0.5–0°C. Pesticide analysis was previously carried out, and no sign of these substances was found, assuring no interference of pesticides with our results.

Preparation of lyophilized fruit extract and anthocyanin quantification

Mixture of fresh berries from the cultivars and selections described above were mechanically triturated and later lyophilized and maintained sheltered from light. Anthocyanins were isolated following the procedure previously.13 For the experiments, lyophilized berries were homogenized in 96% ethanol, agitated for 30 minutes, and centrifuged at 0.5 g for 15 minutes. Supernatants were filtered through filter paper and concentrated by rotary evaporation at 30°C. After relyophilization, extracts were stored until the time of administration to the animals, when they were redissolved in distilled water. These ethanol extracts contained 999 mg of anthocyanins/100 g, and this value was used for dosage calculation. The daily quantity of extract offered to animals was calculated in order to provide 3.2 or 6.4 mg/kg/day anthocyanins. During the whole procedure, including at the time of administration, the extract was kept sheltered from light.

Antinociceptive activity

For the study of antinociceptive activity, mice were divided into four (in the writhing, hot plate, and tail-flick tests) or five (in the formalin test) groups. One group, which served as the negative control group, was pretreated with distilled water in the appropriate volume. Two groups were pretreated with the V. ashei extract, with one group receiving anthocyanins at a 3.2 mg/kg/day dose via oral gavage and the other receiving a 6.4 mg/kg/day dose, for 21 days (chronic model) and at 60 minutes prior to tests (acute model) in all cases. These doses of rabbiteye blueberry anthocyanins are based on previous work4,14–16 and pilot studies in mice (data not shown).

Finally, two positive control groups were pretreated with reference drugs, with the first receiving morphine (10 mg/kg, Dinomorf®, Cristália, São Paulo, SP, Brazil), the reference opioid analgesic, and the second receiving diclofenac (5 mg/kg, Cataflan®, Novartis, São Paulo), the reference anti-inflammatory nonsteroidal drug. For the hot plate and tail-flick test, only morphine was used as a reference drug. All treatments were administered intraperitoneally 30 minutes before the start of each test. Formaldehyde and acetic acid were purchased from Delaware® (Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil). Drugs were dispersed or dissolved in distilled water for administration.

Tests

Formalin-induced pain in mice

The procedure used was similar to previously described methods.17 Animals received 20 μL of 2.5% formalin (0.92% formaldehyde) made up of phosphate buffer solution, which was injected under the surface of the right hind paw. The amount of time spent licking the injected paw was measured with a chronometer and was considered as an indication of pain. Initial nociceptive scores normally peaked at 5 minutes (first phase) and 15–30 minutes after formalin injection (second phase), representing the neurogenic and inflammatory pain responses, respectively. In the first experiment, animals were treated with vehicle (10 mL/kg, i.p.), V. ashei extract (3.2 and 6.4 mg/kg, p.o.), or standard drugs (diclofenac sodium 5 mg/kg or morphine 10 mg/kg), 60 minutes before formalin injection. After intraplantar injection of formalin, animals were immediately placed into a glass cylinder 20 cm in diameter, and the time spent licking the injected paw was determined. In a second experiment, with chronic treatment, the same substances were used, with the exception of morphine.

Acetic acid-induced writhing in mice

This test was conducted usinging the method described by Collier et al.,18 with minor modifications. In the first experiment, animals were treated with vehicle, V. ashei extract (3.2 or 6.4 mg/kg/, p.o.), or morphine (10 mg/kg, s.c.). Sixty minutes after treatments, mice in all groups received an acetic acid injection (0.6%, 0.45 mL per mouse, i.p.). At 5 minutes after the acetic acid injection, pairs of mice were individually placed into glass cylinders 20 cm in diameter, and the number of abdominal constrictions was counted cumulatively over a period of 25 minutes. Antinociceptive activity was expressed as the reduction of the number of constrictions in mice pretreated with extracts or morphine. In the second experiment, the same treatments (except morphine) were administered for 21 days, and afterwards the tests were performed.

Hot plate test

The hot plate test was used to measure latency response, according to method previously described by Eddy and Leimbach,19 with minor modifications. All animals were selected beforehand, based on their reactivity in the model. Mice that exhibited a pretreatment reaction time greater than 12 seconds were not used in subsequent tests. In the first experiment, mice were treated with V. ashei extract (3.2–6.4 mg/kg, p.o.), vehicle, or morphine (10 mg/kg, i.p.), and 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes after the treatments, mice were placed individually on a hot plate (Insight®, Insight Equipamentos, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil) maintained at 54 ± 1°C. We recorded the time (in seconds) that elapsed until the animal jumped or licked one of its hind paws, and this time was considered to be the reaction time. A cutoff time of 30 seconds was imposed to avoid tissue damage. This test was also performed using the same treatments (with the exception of morphine) for 21 days.

Tail-flick assay

The antinociceptive effect of V. ashei berry extract was also evaluated based on the measurement of avoidance response latency time, elicited when pain was induced by application of radiant heat to the animal's tail.20 Mice were treated with vehicle, V. ashei extract (6.4 mg/kg/), or morphine (10 mg/kg). The time spent until the mouse flicked its tail was measured using a Letica (Barcelona, Spain) tail-flick unit. Latency time was recorded before and after 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes of pretreatments. A maximum latency time of 30 seconds was imposed in order to avoid tissue damage. Other groups were treated only with extract (6.4 mg/kg/day p.o.) for 21 days and then tested.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM values. Comparisons between groups were performed by analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett's or the Student-Newman-Keuls tests. Differences between experimental groups with P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Antinociceptive activity

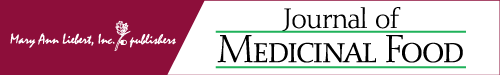

Results presented in Figure 1 show that V. ashei extract (3.2 and 6.4 mg/kg) at both doses and treatments produced inhibition of acetic acid-induced abdominal constrictions in mice, with maximum inhibition calculated for the acute treatment as 27.74% and 46.73%, respectively (Fig. 1A) and 27.59% (for both doses) in the chronic treatment (Fig. 1B). We also observed in this model the significant effect of morphine against nociception induced by acetic acid, with maximum inhibition of 98.37% (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Effect of (A) acute and (B) chronic treatment with V. ashei extract (3.2 and 6.4 mg/kg, p.o.) and morphine (10 mg/kg, s.c.) on the acetic acid test in mice. Data are mean ± SEM (bars) values for 10 animals per group. Asterisks denote significance levels, compared to the control groups (vehicle): *P < .05, ***P < .001, by analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's post hoc test.

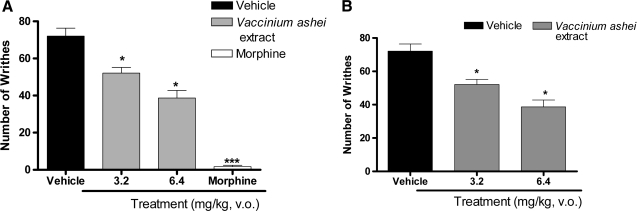

The results of formalin-induced pain in mice are displayed in Figure 2. During the first phase, with acute treatments (Fig. 2A), differences among groups were significant only for animals treated with morphine. However, in the second phase of formalin-induced nociception with the V. ashei extract treatment at a dose of 6.4 mg/kg, diclofenac sodium and morphine were effective in reducing pain when compared to the control group, with maximum inhibition of 72.61%, 93.98%, and 59.12%, respectively. In addition, after prolonged administration (Fig. 2B), V. ashei extract (3.2 mg/kg) significantly inhibited (77.28%) licking behavior during the first phase. In the second phase of experiment, the 3.2 and 6.4 mg/kg doses of extract, as well as diclofenac sodium, were effective, inhibiting the pain by 96.23%, 96.95%, and 88.2%, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Effect of (A) acute (first and second phases) and (B) chronic (first and second phases) treatment with V. ashei extract (3.2 and 6.4 mg/kg, p.o.), sodium diclofenac (Diclof; 5.0 mg/kg, p.o.), and morphine (Morph; 10 mg/kg, s.c.) on formalin-induced pain. The total time (mean ± SEM) spent licking the hind paw was measured in the first phase (0–5 minutes) and the second phase (15–30 minutes) after intraplantar injection of formalin into the hind paws of the mice. Data are mean ± SEM (bars) values for 10 animals per group. Asterisks denote significance levels compared to the control groups (vehicle): *P < .05, **P < .01, by analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's post hoc test.

To confirm the antinociceptive effect of V. ashei extract against other painful stimulus, we also used the hot plate and tail-flick tests. Tables 1 and 2 show the effects of the extract (3.2 and 6.4 mg/kg, p.o.) in the hot plate test. In the acute administration (at a dose of 3.2 mg/kg), values were significant 120 and 150 minutes after the treatment; however, in the group treated with the 6.4 mg/kg dose, there was a significant increase in reaction time after 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes, compared to the control group. The same pharmacological profile was observed with the positive control, morphine (Table 1). In addition, after the prolonged treatment we found a significant (P < .05) increase in reaction time, for both doses, at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes (Table 2).

Table 1.

Antinociceptive Effect of a Single Treatment with V. ashei Extract on Heat-Induced Pain in Mice (Hot Plate Test)

| |

Latency (minutes) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (mg/kg) | 0 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 |

| Control | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 7.1 ± 1.3 | 6.7 ± 0.9 | 6.7 ± 0.7 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 9.1 ± 1.9 |

| Morphine (10) | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 27.1 ± 1.7* | 29.4 ± 0.6* | 29.9 ± 0.1* | 30.0 ± 0. 0* | 30.0 ± 0.0* |

| Extract (3.2) | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 10.6 ± 2.2 | 15.0 ± 1.5* | 13.7 ± 1.8* | 22.9 ± 2.3* |

| Extract (6.4) | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 15.0 ± 1.6* | 16.4 ± 2.2* | 21.1 ± 2.2* | 23.1 ± 2.0* | 25.4 ± 1.8* |

Data are mean ± SEM values for 10 animals per group. Student-Newman-Keuls analysis shows that all groups treated with morphine and extract (6.4 mg/kg) at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes after administration are significantly different from the control group (*P < .05) and that extract (3.2 mg/kg)-treated groups were significantly different from the control group (*P < .05) only at 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes after administration.

Table 2.

Antinociceptive Effect of Prolonged Treatment with V. ashei Extract on Heat-Induced Pain in Mice (Hot Plate Test)

| |

Latency (minutes) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (mg/kg) | 0 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 |

| Control | 7.4 ± 1.8 | 9.0 ± 2.5 | 7.9 ± 1.8 | 10.6 ± 2.6 | 9.4 ± 2.7 | 8.7 ± 2.2 |

| Extract (3.2) | 13.0 ± 3.0 | 26.2 ± 2.5* | 26.4 ± 2.1* | 26.5 ± 2.3* | 30.0 ± 0.0* | 27.67 ± 1.8* |

| Extract (6.4) | 7.1 ± 1.4 | 19.0 ± 3.3* | 23.7 ± 2.4* | 24.0 ± 2.4* | 26.6 ± 1.86* | 26.9 ± 1.6* |

Data are mean ± SEM for 10 animals per group. Student-Newman-Keuls analysis shows that all groups treated with both concentrations of extract (3.2 mg/kg and 6.4 mg/kg) at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes after administration are significantly different from the control group (*P < .05).

In the tail-flick test, acute and prolonged administration of V. ashei extract (6.4 mg/kg) significantly lengthened tail-flick latencies (Tables 3 and 4). As expected, the highest antinociceptive activity coincided with increased levels of phenolic compounds and administration time.

Table 3.

Antinociceptive Effect of a Single Treatment of V. ashei Extract on the Tail-Flick Test

| |

Latency (minutes) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (mg/kg) | 0 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 |

| Control | 8.4 ± 1.4 | 11.9 ± 2.3 | 12.8 ± 1.2 | 12.4 ± 0.8 | 13.1 ± 1.0 | 13.2 ± 1.4 |

| Morphine (10) | 8.8 ± 1.9 | 30.0 ± 0.0* | 29.4 ± 0.6* | 28.1 ± 1.4* | 24.5 ± 2.7* | 26.2 ± 2.6* |

| Extract (6.4) | 7.0 ± 0.7 | 23.4 ± 2.8* | 23.8 ± 2.7* | 24.7 ± 2.2* | 26.90 ± 1.3* | 26.4 ± 1.8* |

Data are mean ± SEM values for 10 animals per group. Student-Newman-Keuls analysis shows that the morphine, extract (3.2 mg/kg), and extract (6.4 mg/kg) groups at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes after administration are significantly different from the control group (*P < .05).

Table 4.

Antinociceptive Effect of Prolonged Treatment with V. ashei Extract on the Tail-Flick Test

| |

Latency (minutes) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (mg/kg) | 0 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 |

| Control | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 10.4 ± 1.7 | 10.9 ± 2.4 | 11.8 ± 2.4 | 12.0 ± 2.4 | 9.5 ± 0.9 |

| Extract (6.4) | 6.4 ± 2.3 | 20.4 ± 2.3* | 20.1 ± 1.4* | 20.5 ± 2.2* | 20.1 ± 1.8* | 18.5 ± 2.0* |

Data are mean ± SEM values for 10 animals per group. Student-Newman-Keuls analysis shows that all groups treated with extract (6.4 mg/kg) at 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes after administration are significantly different from the control group (*P < .05).

Discussion

The antinociceptive activity of V. ashei extract was evaluated using both chemical and thermal methods of nociception in mice. The use of different models is significant in the detection of antinociceptive properties in a substance, considering that using a variety of stimuli can recognize different types of pain and reveal the actual nature of antinociceptive test drugs.21

The acetic acid-induced writhing test is very sensitive and capable of detecting antinociceptive effects of substances at dose levels that may appear inactive in other methods, such as the hot plate test.22 The abdominal constrictions provoked by acetic acid in the intraperitoneal cavity triggers a diversity of mediators, such as bradykinin and prostaglandins (prostaglandin I2), as well as some cytokines such as interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-8.23 These mediators activate chemosensitive nociceptors that contribute to the development of inflammatory pain. In this model, the antinociceptive effect of the V. ashei extract may be due to its action on visceral receptors sensitive to acetic acid, to inhibition of production of algogenic substances, or even to central-level inhibition of the transmission of painful messages. However, with this test only we may not be able to indicate the antinociceptive effect mechanism of V. ashei extract because many agents are able to reduce pain induced by acetic acid (antihistamines24 and myorelaxant25).

V. ashei extract was also evaluated in the formalin test, with excellent effects during the second phase of formalin-induced pain. The subcutaneous injection of formalin in the paws of mice induces a biphasic nociceptive response. The early phase (neurogenic pain) results from the chemical stimulation of myelinated and unmyelinated nociceptive afferent fibers, principally C fibers.26 The late phase is a persistent period caused by local tissue inflammation and by functional changes in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. It is believed that these changes in the spinal cord initiate by C-fiber barrage during the early phase.26 Both phases are sensitive to centrally acting drugs such as opioids,27 but the second phase is also sensitive to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids. In this model, V. ashei inhibited the licking response of mice in the second phase, suggesting this compound exerts its antinociceptive effects connected with peripheral mechanisms. The results are shown in Figure 2.

Reports from other laboratories26,28 have demonstrated that intraplantar injection of formalin in animals produces significant increases in spinal levels of different mediators, such as excitatory amino acids, prostaglandin E2, nitric oxide, and kinins among other peptides. Moreover, tachykinin receptor antagonists, nitric oxide synthase inhibitors, N-methyl-d-asparate receptor antagonists, opioids, α2-adrenoceptor agonists, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs administered by systemic spinal and supraspinal methods were all found to be effective in antagonizing formalin-induced nociception.29,30

The antinociceptive effect of V. ashei extract was investigated by the standard Eddy's hot plate method19 as a thermal pain experimental model.31,32 Analysis of the data revealed a statistically significant difference in the hot plate reaction time between the test and the control groups (P < .05). Thus V. ashei exhibited a significant analgesic effect at the doses studied after 1 hour and after 21 days of administration. This analgesic action and its antinociceptive activity might be centrally mediated.

The hot plate test is a central antinociceptive model in which opioid agents exert their analgesic effects via supraspinal and spinal receptors. Comparing reaction times obtained for animals treated with the V. ashei extracts and the control values, it is apparent that the V. ashei extract caused a considerable prolongation of latency times, which is indicative of centrally mediated activity.

Another evidence of a possible central effect of V. ashei extract was detected through the tail-flick test. This task is sensitive in assessing the effectiveness of centrally acting analgesics.33 Data regarding antinociceptive effects suggest that V. ashei extract at a 6.4 mg/kg dose has a central antinociceptive effect, as evidenced by the prolonged delay in response when animals were subjected to nociceptive stimulus in this test. These findings also suggest that V. ashei berry extracts can affect opioid receptors, but additional experiments are necessary to confirm this suggestion.

In this context as been reported that polyphenols, including some anthocyanins, possess oral bioavailability in rodents15,34,35 and that they are able to cross the rat blood–brain barrier after red berry supplementation,36,37 as well as after a single administration, suggesting that these compounds can feasibly have a direct effect on brain processes. Detection of anthocyanins in brain was very fast, less than 30 minutes.38 Pharmacokinetic evidence also suggests that the concentrations of the parent glycosides and their glucuronide derivatives are high in early blood samples (0–5 hours), with increasing methylation occurring over time. This evidence suggests that the bioactivity of anthocyanins is likely altered over time as a result of metabolic transformation post-consumption.39 These data are consistent with the duration of observed effects on pain behavior in our studies.

Results similar to ours have been reported for other anthocyanin-rich extracts, including tart cherry,16 proanthocyanidin shellegueain A from Polypodium feei METT,4 and Vaccinium corymbosum.40 Evaluation of the pharmacological properties of the compounds isolated from the active fractions pointed out that anthocyanins possess strong antioxidant/anti-inflammatory activities, as well as the ability to inhibit lipid peroxidation and the inflammatory mediators cyclooxygenase-1 and -2, including cell migration. Cyanidins are reported to possess anti-inflammatory properties comparable to those of commercial products naproxen and ibuprofen.7–9 It was therefore concluded that anthocyanins contribute, in full or in part, to the antinociceptive activities of V. ashei extract. However, further studies are needed to isolate the active constituents responsible for the observed effect and to reveal the possible mechanisms of action responsible for the analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities.

Acknowledgments

D.M.B., M.M.d.S., and A.T.H. are research fellows from CNPq, Brazil. This work was supported by FAPERGS (grant 04/04989) and CNPq, Brazil. The authors wish to thank Msc. Maíra Proietti for English suggestions.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Yi W. Fischer J. Krewer G. Akoh CC. Phenolic compounds from blueberries can inhibit colon cancer cell proliferation and induce apoptosis. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;7:7320–7329. doi: 10.1021/jf051333o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prior RL. Cao G. Martin A. Sofic E. McEwen J. O'Brien C. Lischner N. Ehlenfeldt M. Kalt W. Krewer G. Mainland M. Antioxidant capacity as influenced by total phenolic and anthocyanin content, maturity, and variety of Vaccinium species. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:2686–2693. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kong JM. Chia LS. Goh NK. Chia TF. Brouillard R. Analysis and biological activities of anthocyanins. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:923–933. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00438-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subarnas A. Wagner H. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity of the proanthocyanidin shellegueain A from Polypodium feei METT. Phytomedicine. 2000;7:401–405. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(00)80061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalbó S. Jürgensen S. Horst H. Soethe DN. Santos ARS. Pizzolatii MG. Ribeiro-do-Valle MR. Analysis of the antinociceptive effect of the proanthocyanidin-rich fraction obtained from Croton celtidifolius barks: evidence for a role of the dopaminergic system. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;85:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee B. Bagchi D. Beneficial effects of a novel IH636 grape seed proanthocyanidin extract in the treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Digest. 2001;63:203–209. doi: 10.1159/000051890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H. Nair MG. Strasburg GM. Chang YC. Booren AM. Gray JI. Dewitt DL. Antioxidant and antiinflammatory activities of anthocyanins and their aglycone, cyanidin, from tart cherries. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:294–296. doi: 10.1021/np980501m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H. Nair MG. Strasburg GM. Booren AM. Gray I. Dewitt DL. Cyclooxygenase active bioflavonoids from Balaton tart cherry and their structure activity relationships. Phytomedicine. 2000;7:15–19. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(00)80016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seeram NP. Momin RA. Nair MG. Bourquin LD. Cyclooxygenase inhibitory and antioxidant cyanidin glycosides in cherries and berries. Phytomedicine. 2001;8:362–369. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nijveldt RJ. van Nood E. van Hoorn DEC. Boelens PG. van Norren K. van Leeuwen PAM. Flavonoids: a review of probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:418–425. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willain-Filho A. Cechinel-Filho V. Olinger L. De-Souza MM. Quercetin: Further investigation of its antinociceptive properties and mechanisms of action. Arch Pharm Res. 2008;31:713–721. doi: 10.1007/s12272-001-1217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmermann M. Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animal. Pain. 1983;16:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Pharmacopoeia Portuguesa [CD-ROM] 7th. Infarmed; Lisbon: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barros DM. Amaral OB. Izquierdo I. Geracitano L. Bassols Raseira MC. Henriques AT. Ramirez MR. Behavioral and genoprotective effects of Vaccinium berries intake in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;84:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank J. Kamal-Eldin A. Lundh T. Määttä K. Törrönen R. Vessby B. Effects of dietary anthocyanins on tocopherols and lipids in rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:7226–7230. doi: 10.1021/jf025716n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tall JM. Seeram NP. Zhao C. Nair MG. Meyer RA. Raja SN. Tart cherry anthocyanins suppress inflammation-induced pain behavior in rat. Behav Brain Res. 2004;153:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunskaar S. Hole K. The formalin test in mice: dissociation between inflammatory and non-inflammatory pain. Pain. 1987;30:103–114. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collier HOJ. Dinneen JC. Johnson CA. Schneider C. The abdominal constriction response and its suppression by analgesic drugs in mice. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1968;32:295–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1968.tb00973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eddy NB. Leimbach D. Synthetic analgesics. II. Dithienylbutenyl and dithienylbutenylamines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1953;107:385–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DAmour FE. Smith DL. A method for determining loss of pain sensation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1941;72:74–79. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergerot A. Holland PR. Akerman S. Bartsch T. Ahn AH. Maassen Van Den Brink A. Reuter U. Tassorelli C. Schoenen J. Mitsikostas DD. van den Maagdenberg AM. Goadsby PJ. Animal models of migraine: looking at the component parts of a complex disorder. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1510–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bentley GA. Newton SH. Starr J. Evidence for an action of morphine and enkephalins on sensory nerve endings in the mouse peritoneum. Br J Pharmacol. 1981;73:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb10425.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikeda Y. Ueno A. Naraba H. Ohishi S. Involvement of vanilloid receptor VR1 and prostanoids in the acid induced writhing responses of mice. Life Sci. 2001;69:2911–2919. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01374-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naik DG. Mujumdar AM. Wagole RJ. Kulkarni DK. Kumbhojkar MS. Pharmacological studies of Sterculia foetida leaves. Pharmacol Biol. 2000;38:13–17. doi: 10.1076/1388-0209(200001)3811-BFT013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koyama K. Imaizumi T. Akiba M. Kinoshita K. Takahashi K. Suzuki A. Yano S. Horie S. Watanabe K. Naoi Y. Antinociceptive components of Ganoderma lucidum. Planta Med. 1997;63:224–227. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tjølsen A. Berge O. Hunskaar S. Rosland JHK. Hole K. The formalin test: an evaluation of the method. Pain. 1992;52:5–17. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90003-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shibata M. Ohkubo T. Takahashi H. Inoki R. Modified formalin test: characteristic biphasic pain response. Pain. 1989;38:347–352. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos AR. Gadotti VM. Oliveira GL. Tibola D. Paszcuk AF. Neto A. Spindola HM. De- Souza MM. Rodrigues AL. Calixto JB. Mechanisms involved in the antinociception caused by agmatine in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:1021–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malmberg AB. Yaksh TL. The effect of morphine on formalin-evoked behaviour and spinal release of excitatory amino acids and prostaglandin E2 using microdialysis in conscious rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114:1069–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaplan SR. Malmberg AB. Yaksh TL. Efficacy of spinal NMDA receptor antagonism in formalin hyperalgesia and nerve injury evoked allodynia in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:829–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nemirovsky A. Chen L. Zelma V. Jurna I. The antinociceptive effect of the combination of spinal morphine with systemic morphine or buprenorphine. Anesthesiol Analg. 2001;93:197–203. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200107000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miaskowski C. Taiwo YO. Levine JD. Antinociception produced by receptor selective opioids. Modulation of supraspinal antinociceptive effects by spinal opioids. Brain Res. 1993;608:87–93. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90777-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talhouk RS. Karam C. Fostok S. El-Jouni W. Barbour EK. Anti-inflammatory bioactivities in plant extracts. J Med Food. 2007;10:1–10. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2005.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsumoto H. Inaba H. Kishi M. Tominaga S. Hirayama M. Tsuda T. Orally administered delphinidin 3-rutinoside and cyanidin 3-rutinoside are directly absorbed in rats and humans and appear in the blood as intact forms. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:1546–1551. doi: 10.1021/jf001246q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGhie TK. Ainge GD. Barnett LE. Cooney JM. Jensen DJ. Anthocyanin glycosides from berry fruit are absorbed and excreted unmetabolized by both humans and rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:4539–4548. doi: 10.1021/jf026206w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrés-Lacueva C. Shukitt-Hale B. Galli RL. Jauregui O. Lamuela-Raventos RM. Joseph JA. Anthocyanins in aged blueberry-fed rats are found centrally and may enhance memory. Nutr Neurosci. 2005;8:111–120. doi: 10.1080/10284150500078117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Talavera S. Felgines C. Texier O. Besson C. Gil-Izquierdo A. Lamaison JL. Remesy C. Anthocyanin metabolism in rats and their distribution to digestive area, kidney, and brain. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:3902–3908. doi: 10.1021/jf050145v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Passamonti S. Vrhovsek U. Vanzo A. Mattivi F. Fast access of some grape pigments to the brain. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:7029–7034. doi: 10.1021/jf050565k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazza G. Kay CD. Cotrell T. Holub BJ. Absorption of anthocyanins from blueberries and serum antioxidant status in human subjects. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:7731–7737. doi: 10.1021/jf020690l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torri E. Lemos M. Caliari V. Kassuya CAL. Bastos JK. Andrade SF. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive properties of blueberry extract (Vaccinium corymbosum) J Pharm Pharmacol. 2007;59:591–596. doi: 10.1211/jpp.59.4.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]