Summary

Hostility is associated with a number of metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including waist-hip ratio, glucose, and triglycerides. Along with hostility, many of these measures have also been shown to be associated with reduced central serotonergic function. We have previously reported that a citalopram intervention was successful in reducing hostility by self-report assessment (Kamarck, et al., 2009). Here we examine the effects of this serotonergic intervention on metabolic risk factors in the same sample. 159 healthy adults with elevated hostility scores were randomized to citalopram or placebo for a 2-month period. Citalopram favorably changed metabolic risk factors, including waist circumference (p = .003), glucose (p=.02), HDL cholesterol (p= .04), triglycerides (p=.03), insulin sensitivity (p = .045) and diastolic blood pressure by automated assessment (p = .0021). All of these metabolic changes were significantly mediated by treatment-related changes in body mass index (in most cases, p < .01). In addition, the changes in blood glucose were significantly mediated by treatment-related changes in hostility (p < .05). Mechanisms accounting for these associations remain to be explored.

Keywords: hostility, citalopram, metabolic syndrome, randomized clinical trial, ssri, glucose

1. Introduction

A large body of evidence suggests that otherwise healthy individuals who have high scores on measures of dispositional hostility may be at increased risk for developing coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality (Everson-Rose & Lewis, 2005; Miller, Smith, Turner, Guijarro, & Hallet, 1996). Hostility appears to be important not only by virtue of its independent associations with CHD and mortality, but also because of its well-documented links with other behavioral and biological risk factors for cardiovascular disease. A recent meta-analysis of 27 relevant reports, for example, has shown that hostility, as assessed by the widely used Cook Medley scale (Cook & Medley, 1954), is reliably associated with metabolic risk factors, including waist-hip ratio, glucose and insulin resistance, lipid ratios, and triglycerides (Bunde & Suls, 2006). Each of these factors is an important component of the metabolic syndrome. Such findings highlight the importance of hostility, not only as a precursor of CHD, but as a marker of risk factor covariation as well.

One of the potential mechanisms linking hostility with metabolic risk factors involves variations in central serotonergic activity. Individual differences in central serotonergic activity are commonly indexed by CSF concentrations of serotonin’s principal metabolite or by neuroendocrine (e.g., prolactin) responses to acute administration of a serotonin agonist. Using such measures, reduced central serotonergic function has been shown to be associated with aggression in primates (Botchin, Kaplan, Manuck, & Mann, 1993; Higley, King, et al., 1996; Higley, Mehlman, et al., 1996) and with measures of hostility in humans, especially among men (Cleare & Bond, 1997; Coccaro, 1997; Manuck, et al., 1998). Evidence also suggests that reduced central serotonergic function may be associated with an increased prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in community samples of human volunteers, as assessed by NCEP and IDF criteria (Muldoon, et al., 2006; Muldoon, et al., 2007). A recent report suggests that central serotonergic function may be related to multiple indices of hostility and metabolic function in the same sample (Williams, et al., 2010). Thus, observed associations between hostility and metabolic risk factors may be accounted for by common neurobiological determinants.

Each of the associations described above is drawn from correlational studies. A complementary, experimental approach would allow us to determine if these observed associations are causal in nature. A small experimental literature has suggested that fluoxetine, a selective serotonergic reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) that enhances synaptic availability of serotonin, may also be associated with short term improvements in metabolic function in small samples of diabetic, impaired glucose tolerant, or obese individuals (Breum, Bjerre, Bak, Jacobsen, & Astrup, 1995; Daubresse, et al., 1996; Gray, Fujioka, Devine, & Bray, 1992; Maheux, Ducros, Bourque, Garon, & Chiasson, 1997; O'Kane, Wiles, & Wales, 1994; Potter van Loon, et al., 1992). We took advantage of a larger placebo-controlled SSRI intervention study to examine the possible impact of hostility changes on metabolic risk factors, and the possible role of serotonergic function in driving the relationship between hostility and markers of the metabolic syndrome. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine the effects of experimentally-induced changes in hostility on alterations in metabolic risk.

The STAHR (Stress Treatment and Health Risk) study was a placebo-controlled study designed to examine the effects of citalopram on hostility and other cardiovascular risk factors in high hostile healthy adults. Published results from this study demonstrated significant drug intervention effects on hostile affect and state anger (Kamarck, et al., 2009). In the current report, we examine the effects of citalopram on metabolic risk factors that have been previously linked with hostility, and we explore the potential role of hostility changes in accounting for any observed drug-related changes in metabolic function.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

We recruited healthy middle aged adults (ages 30–50) with elevated scores on two standard measures of hostility (see below). Exclusionary criteria included history of CVD or other chronic medical conditions (e.g., diabetes), use of medication for cholesterol or high blood pressure (or use of BP medications within the past year), and use of other medications with autonomic effects. Those with fasting blood glucose over 140 mg/ML or blood pressure > 160/100 mmHg were also excluded and were referred immediately for treatment. All of these criteria were designed to reduce the confounding effects of concurrent medication or treatments on metabolic risk.

We excluded those with current Axis I DSM-IV diagnoses, those with excessive alcohol use (> 14 drinks/week or > 2 binges per week), current use of street drugs by self report, or positive urine drug screens, those on any pre-existing psychotropic medications, and those who had taken SSRIs within the past 2 months. To reduce any potential teratogenic risk of the drugs, we also excluded pregnant women (positive pregnancy test), those who were planning to become pregnant, and premenopausal women unwilling to commit to use of a double barrier contraceptive method during the course of their participation in the study (Kamarck, et al., 2009).

2.2. Overall procedure

Mass mailings with self-addressed return postcards were sent to residents of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, targeting the age range of interest. Telephone screening interviews were conducted with potential participants who returned the postcard forms. Potential participants were administered a screening instrument by phone which included items from the Cook-Medley and the Buss-Durkee hostility inventories (Barefoot, Dodge, Peterson, Dahlstrom, & Williams, 1989; Buss & Durkee, 1957; Cook & Medley, 1954) and those in the top tertile on both of these instruments were selected, based upon a normative sample. Interested individuals who passed all telephone screening criteria were invited to participate in a laboratory screening session (Visit 1), during which they provided written informed consent followed by administration of a more detailed medical history interview (including anthropometric measures and self-reported smoking history), a portion of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002)) to rule out current Axis I diagnosis (see above), a clinic blood pressure screening and finger stick for blood glucose screen, a urine drug screen (to rule out current use of street drugs including cocaine, opiates, and amphetamine), a urine pregnancy test, and several additional questionnaires.

229 individuals enrolled in the study. These participants attended 5 additional “pre-treatment visits” (Visits 2–6) over a 1-1/2 month period (range of 17–108 days). Additional risk factor information was assessed during Visit 2, Visit 3 involved a series of laboratory stressors (not reported here), and Visits 4–6 involved training and feedback for self-report field diary assessments (not reported here). Other questionnaires and interviews were also administered during these pre-treatment visits.

Following the pre-treatment period, subjects were scheduled for an appointment in the medication clinic (Visit 7). They were administered a second informed consent procedure by the study psychiatrist (RFH) during which risks and side effects associated with the study medication were described in greater detail. A urine pregnancy test was re-administered to eligible participants and acceptable methods of contraception were discussed. Participants who remained eligible and interested were randomized to drug or placebo intervention, using a computer generated randomization list. Randomization was performed by the Investigational Drug Service in the School of Pharmacy at the University of Pittsburgh; investigators, research staff and participants were blinded as to condition assignment. At the end of Visit 7, participants were accompanied to the pharmacy facility where they were provided with their drug/placebo bottles. Randomization was implemented by pharmacy workers using information received by the IDS. Drug/placebo administration use was initiated immediately following this visit. 69 subjects were dropped during pre-treatment assessment or prior to randomization (for example, due to schedule conflicts or eligibility concerns), leaving 160 randomized subjects.

The target sample size of 160 was based upon power analyses that drew upon published results; in this study, 81 subjects were randomized to drug and 79 were randomized to placebo. Data for one of these subjects were destroyed by request, leaving us with 159 randomized subjects.

Visit 7 and three additional “treatment titration” visits (Visit 8–10) were completed over a 1–1/2 month period (range of 39–61 days). During each of these visits, each approximately 30 mins in duration, participants met individually with a clinical research nurse. Pill counts were conducted, side effects were discussed, and the new drug dosage for the following visit was determined. A “fixed flexible” dosage range was prescribed: All subjects in the active intervention and placebo conditions were started on a 10 mg (one pill) dose. Those without significant side effects were advised to incrementally increase the dose at each visit up to a maximum of 40 mg (4 pills) by the end of Visit 10. A final medication review visit (Visit 11) was scheduled 2 weeks after the final dose was prescribed, during which the “fixed treatment” period began.

During the five “fixed treatment” visits (Visit 11–15 over the next month, range of 9–104 days), most of the pre-treatment measures were readministered once. During this period, participants also underwent three blood draws for assessment of citalopram blood concentrations (not examined here). Following Visit 15, participants underwent a two-week withdrawal period, during which pill dosage was gradually reduced. Visit 16 was a debriefing visit scheduled following the withdrawal period; participants met with investigators in the study (RFH, TWK) to discuss their reactions to the pills and to the study procedures. Consulting a confidential envelope provided on each participant by the Investigational Drug Service, the PI (TWK) debriefed the participants as to their condition assignment at this time. If they expressed interest, participants were referred for further psychological or pharmacologic treatment.

Data collection for this study spanned a 49-month period, from January 2002 – March 2006. The study was conducted in compliance with the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

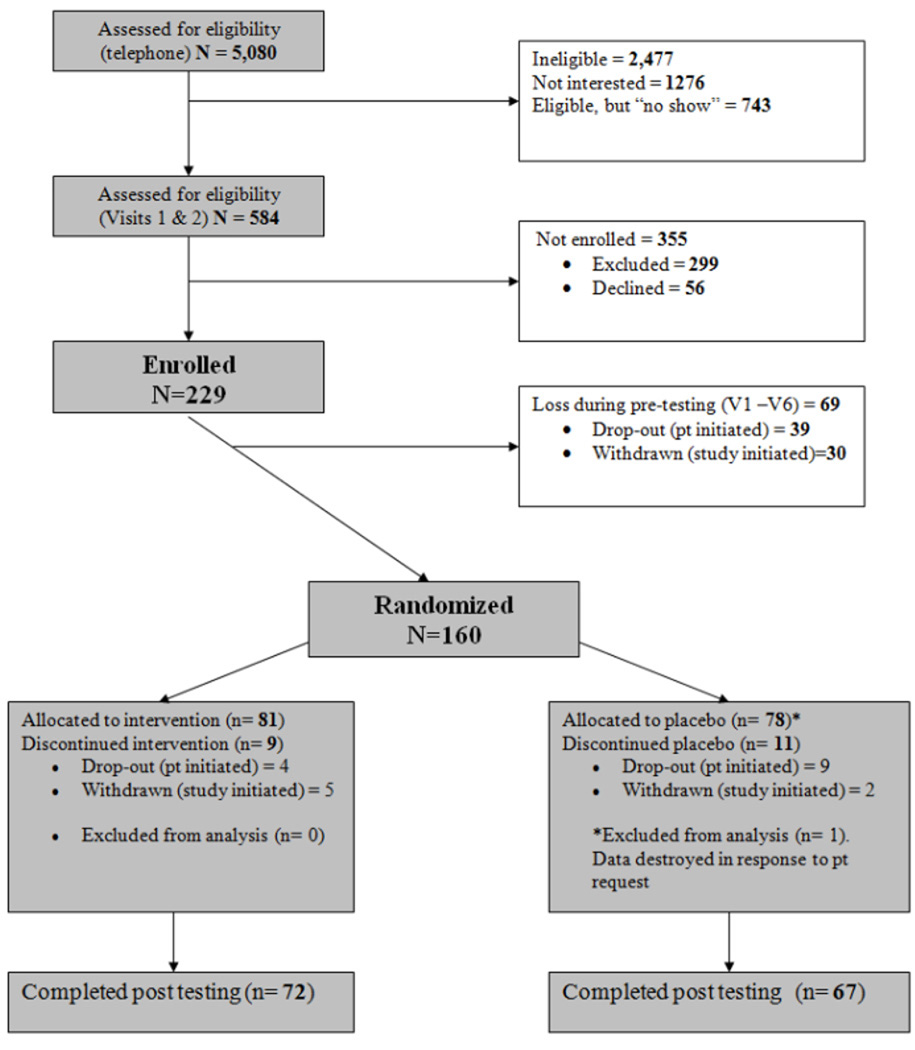

87 % (n = 139) of randomized participants completed the intervention and the end-of-treatment assessments; 72 of these were in the drug condition, and 67 were in the placebo group. See Figure 1, Recruitment Flowchart. All analyses were conducted on the randomized sample of 159, using the intention-to-treat principle, and missing data were imputed using maximum likelihood methods.

Figure 1.

Recruitment flowchart.

2.3. Hostility measures

A series of self-report measures of hostility were administered, including the Cook-Medley Hostility Scale (CMHS) (Cook & Medley, 1954), the Spielberger State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI)(Spielberger, 1988), the Buss Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI) (Buss & Durkee, 1957), and the Buss Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ) (Buss & Perry, 1992). These self-report questionnaires assess multiple aspects of hostility, and each was administered twice, during the pretreatment period and during the fixed treatment period at the end of the study.

As previously described (Kamarck, et al., 2009), when we subjected subscale scores from these measures to factor analysis, we derived a similar three-factor solution for each of the two assessment points, with the derived factors, in each case, representing measures of hostile cognition, hostile affect, and hostile behavior, respectively. An aggregate measure of trait Hostile Affect was derived by combining scores from the BPAQ Anger subscale, the STAXI Trait Anger and Anger Control (negative loading) subscales, and the BDHI Indirect and Irritability subscales; a trait Hostile Behavior score was derived from the BPAQ Verbal Aggression and Physical Aggression subscales along with the BDHI Assault, Verbal, and Negativism subscales; and trait Hostile Cognition was measured based upon scores from the BPAQ Hostility subscale, the BDHI Resentment, Suspicion, and Guilt subcales, the CMHI, and the STAXI Anger-In scale.3 Our primary concern in this current report involved the Hostile Affect measure, since this was the factor that we showed to be associated with significant citalopram intervention effects (Kamarck, et al., 2009).

Other psychosocial characteristics were also assessed but are not examined in this present report, including measures of depressive symptoms, impulsivity, and perceived social support (Kamarck, et al., 2009).

2.4. Adherence measure

A MEMS (Medication Event Monitoring System) cap (ARPEX/AARDEX Union City, CA) was assigned to each participant at the start of the treatment titration period. This is a prescription drug bottle cap equipped with an electronic chip that is activated with each cap closing, used as a measure of medication adherence. Adherence was assessed as the proportion of intervention days during which the bottle cap was opened and closed one or more times outside of the clinic visits.

2.5. Side effects measure

At each of the treatment visits (Visit 8–11), participants were administered a 23-item questionnaire (Somatic Syptom Scale, SSS) inquiring about current physical symptoms potentially relevant to the use of citalopram (e.g., dizziness, nervousness, dry mouth). Number of symptoms endorsed by each participant was averaged across sessions; scores were log transformed to reduce skewness.

2.6. Metabolic risk factors

Metabolic risk factors were assessed on two occasions, once at pre-test (Visit 2), and once during the fixed treatment period (Visit 11). For each of these early morning visits, participants were asked to abstain from food and caffeine for 12 hours. Based upon the five criteria of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) for defining metabolic syndrome, the major dependent measures of interest included waist circumference, fasting glucose, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, and resting blood pressure. We also assessed body mass index and fasting plasma insulin. An estimate of insulin resistance based on the Homeostasis Model Assessment was calculated as follows: HOMA-IR=serum insulin (uIU/mL) × fasting blood glucose (mmol/L)/22.5 (Matthews, et al., 1985; Wallace, Levy, & Matthews, 2004). Assessment procedures for each of these measures are described below

2.6.1. Anthropometric measures

Subjects were asked to remove their shoes and all items from their pockets. Height was measured using a standard wall unit, and weight was assessed using a digital scale. Waist circumference was assessed at the level of the umbilicus during mid-respiration, to the nearest half-centimeter. Weight data were complete at baseline, but follow-up weight data were missing for 22 subjects; 16 were dropouts, and data from 6 additional subjects were missing due to a data collection error. Waist circumference measures were added to the protocol for baseline and follow-up 8 months after the data collection began; therefore, baseline waist data were missing for 17 randomized subjects; 9 of these (including 3 dropouts) were also missing the waist circumference data at follow-up.

2.6.2. Lipid and glucose assays

Following blood draw, serum samples were separated and stored (−70 degrees centigrade). Determinations of serum total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides were performed by the Heinz Nutrition Laboratory, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, which has met the criteria of the Centers for Disease Control-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Lipid Standardization Program since 1982. Fasting serum glucose was oxidized to form gluconate and hydrogen peroxide, then reacted with dye precursors catalyzed by peroxidase, which were detected with standard colorimetry at 540 nm. Serum insulin concentration was measured by radioimmunoassay.

Triglyceride measures and HOMA insulin resistance measures were log transformed to correct for skewness, and HDL cholesterol values were dropped for one participant whose baseline measures (baseline HDL of 102) were more than 4 standard deviations from the mean.

2.6.3. Blood pressure

Resting blood pressure was assessed by standard manual sphygmomanometry in the medical assessment office (Visit 1), and by use of an automated device while sitting at rest in the laboratory (Visit 3).

2.6.3.1. Standard manual sphygmomanometry

Subjects were seated for at least 5 minutes prior to their standard blood pressure assessments. Following guidelines from the American Heart Association (Perloff, et al., 1993), 3 seated manual blood pressure readings were taken, at 2 minute intervals, by a trained research nurse, using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer (Vital Signs Model 63154, Country Technology, Gays Mills, WI). The average of the last 2 readings was used.

2.6.3.2. Automated blood pressure assessment

During a larger psychophysiological assessment protocol, five measures of resting blood pressure were recorded from an automatic auscultatory device (Accutracker DX; Sun Tech Medical Inc., Morrisville, NC) during each of five 6-minute baseline epochs (total of 25 assessments for each person). These measures were averaged to obtain estimates of resting cardiovascular functioning, estimates that, by virtue of the number of readings involved were assumed to be more reliable and representative than those assessed using standard manual sphygmomanometry.

2.7. Health behaviors

To help us examine behavioral contributions to any observed changes in weight or metabolic risk, we collected measures of diet, physical activity, and alcohol consumption, as described below.

2.7.1. Dietary recall

Trained interviewers performed two 24-hour dietary recall interviews during the pre-testing interval (Visits 2–6), and again during the fixed treatment interval (Visits 11–15), using the Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) software developed by the Nutrition Coordinating Center (NCC) at the University of Minnesota (Sievert, Schakel, & Buzzard, 1989). Measures of total 24-hour caloric consumption were calculated from each interview and averaged within each period (pre-test and fixed treatment). Participants who were missing one or more interviews were not scored.

2.7.2. Physical activity

Subjects were equipped with a pedometer (AE120 pedometer, Accusplit, Inc., San Jose, CA) which they were instructed to wear at the waist on the dominant hip throughout the waking day for a 7 day period, during pre-testing (Visit 2) and again during the fixed treatment period (Visit 11). Step counts were calculated for each day and averaged within each period (pre-test and fixed treatment). Subjects were instructed to record the times and occasions during which the monitor was not worn during the monitoring period; when these periods involved physical activity (such as swimming or biking), step counts were corrected based upon the estimated metabolic expenditure associated with that activity, and converted to step equivalent units (steps per minute).

2.7.3. Alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption was assessed during pre-testing (Visit 2) and again during the fixed treatment period (Visit 11) using self-report estimates of wine, beer, and liquor consumption converted to daily grams of alcohol (quantity-frequency method) (Garg, Wagener, & Madans, 1993). Pre-testing assessments were based upon an unspecified time frame (“How often do you…”) and fixed treatment period estimates were based upon the past month (“During the past month, how often have you…”).

2.8. Data analysis

SAS Proc Mixed, which employs Maximum Likelihood estimation, was used to calculate the effects of condition assignment (placebo vs. drug), time (pre-treatment vs. fixed treatment) and their interaction on each of the measures of metabolic risk. When such procedures are used to model the changes in a dependent variable over time, missing data points for such a variable are imputed without the use of list wise deletion, allowing for a fuller utilization of existing data. To verify that any missing data would not change the results, analyses were run using all randomized participants (n = 159, intention-to-treat model) and, again, using only those who completed the intervention (n =139). Because the outcome of these two approaches did not differ, we present only the intention-to-treat model results here.

We have previously shown that this citalopram intervention was associated with significant changes in Hostile Affect (but not with changes in Hostile Behavior or Hostile Cognition) (Kamarck, et al., 2009). In order to examine whether the observed effects of citalopram on metabolic risk might be mediated by changes in hostility, we re-ran each of the condition-by-time effects on metabolic risk with pre- and post- Hostile Affect scores as a time varying covariate. We tested the significance of such potential mediation using MacKinnon’s Assymetrical Confidence Interval method with the program PRODCLIN (MacKinnon, 2008; MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007). In this method, the indirect effect of a mediating variable is assessed as the cross-product of two regression coefficients, one linking the explanatory variable and the mediator (in this case, the regression coefficient associated with the condition-by-time interaction effect on hostility), and the other linking the mediator and the dependent variable (in this case, the regression coefficient describing the association between hostility changes and metabolic changes over the course of the intervention). Because a distribution of a product of two normally distributed variables may not itself be normally distributed, PRODCLIN calculates assymetric confidence intervals for these cross-product terms, based upon the calculated regression coefficients and their respective standard errors.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline sample characteristics

Participants randomized to each of the two conditions did not differ with respect to age, sex, race, education or income. Mean baseline scores were 25.8 (sd=8.5, n=158) for the Cook-Medley Hostility Scale (range=0–50), and 82.8 (sd=16.5, n=158) for the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (range= 29–145) (no condition differences, see (Kamarck, et al., 2009).

Baseline metabolic risk factors, along with baseline measures of body mass index and insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) are presented, by sex and condition, in Table 1. There were significant sex differences in baseline waist circumference (F (1, 139) = 4.59, p = .03), HDL cholesterol (F (1, 157) = 38.19, p < .0001) and blood pressure (SBP for manual readings, F (1, 158) = 6.82, p=.0099; SBP and DBP for laboratory readings, F (1, 154) = 20.53, p < .0001; F (1,154) = 10.90, p = .0012, respectively). There were no significant condition or sex-by-condition interaction effects for any of these variables.

Table 1.

Baseline Measures of Metabolic Risk Factors, by Condition and Sex

| Active Drug Condition |

Placebo Condition |

|

|---|---|---|

| n=42 men, 39 women | n=37 men, 41 women | |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | ||

| Men | 98.7 (11.9)1 | 99.6 (13.1)2 |

| Women | 96.0 (14.3)3 | 91.7 (17.5)3 |

| HDL cholesterol | ||

| Men | 41.6 (9.4) | 43.1 (8.2)4 |

| Women | 51.2 (10.1) | 53.4 (12.1) |

| Triglycerides | ||

| Men | 152.4 (108.1) | 150.6 (98.4) |

| Women | 144.4 (145.9) | 116.9 (67.2) |

| Glucose | ||

| Men | 96.5 (12.2) | 95.3 (7.9) |

| Women | 93.4 (13.0) | 92.3 (10.9) |

| Insulin | ||

| Men | 15.9 (14.3) | 12.8 (6.7) |

| Women | 17.4 (17.8) | 14.1 (9.5) |

| Blood Pressure (Manual) | ||

| SBP | ||

| Men | 109.3 (8.0) | 110.9 (9.2) |

| Women | 106.4 (9.2) | 106.4 (8.9) |

| DBP | ||

| Men | 75.9 (6.1) | 77.3 (8.8) |

| Women | 74.1 (8.3) | 74.7 (7.5) |

| Blood Pressure (Automated) | ||

| SBP | ||

| Men | 116.9 (8.6)5 | 116.0 (9.9) |

| Women | 107.8 (11.7) | 109.4 (12.7) |

| DBP | ||

| Men | 74.9 (6.3)5 | 73.8 (7.5) |

| Women | 70.1 (8.3) | 70.7 (7.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| Men | 29.2 (5.0) | 28.9 (4.2) |

| Women | 31.1 (5.6) | 28.9 (7.3) |

| Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) | ||

| Men | 4.04 (4.60) | 3.08 ((1.80) |

| Women | 4.16 (4.79) | 3.27 (2.43) |

Note. Scores are displayed as M (std).

n=39,

n=33,

n=35,

n=36,

n=41.

Note. HOMA-IR=serum insulin (uIU/mL)xfasting blood glucose (mmol/L)/22.5.

3.2. Dose, adherence, and symptom reports

Among completers (n = 139), 90 % of those in the drug intervention group (65/72) and 88 % of those in the placebo control condition (59/67) successfully transitioned to the maximum pill dose (40 mg or 4 pills daily) by the end of the treatment titration period. The proportion of those taking the maximum pill dose did not differ by condition (Fisher’s exact test p = .79).

Among completers, the average rate of adherence (proportion of days in the study during which the MEMS bottle was opened one or more times, correcting for clinic visits) was 89 % (range= 39 %–100 %, with 82 % of the sample demonstrating adherence on 80 % or more of the days). There were no main effects of condition on rates of adherence (p = .48). (Kamarck, et al., 2009).

There were also no condition differences in somatic symptoms reported during treatment (p = .4) (Kamarck, et al., 2009).

3.3 Drug-related changes in metabolic risk factors

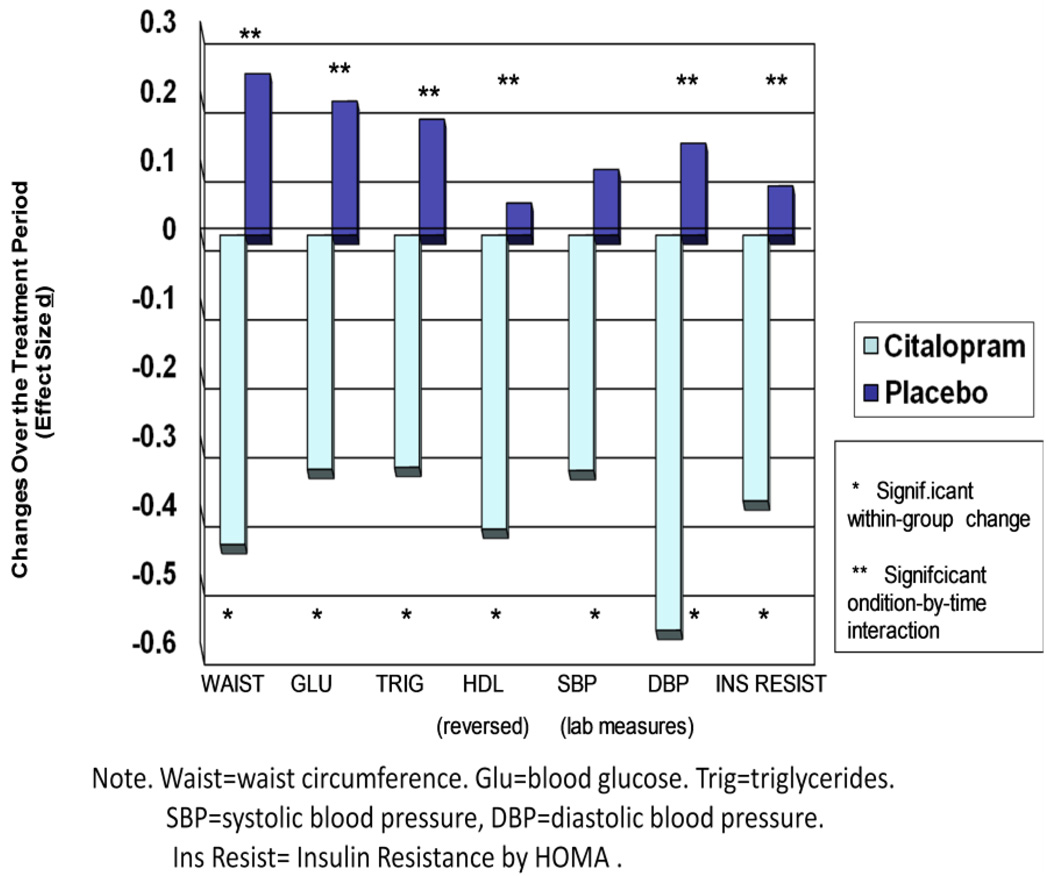

The citalopram intervention was associated with favorable changes in metabolic risk factors, including waist circumference (condition by time (C×T) interaction F (1, 123) = 9.17, p = .003), glucose (C×T F (1, 141) =5.65, p=.02), HDL cholesterol (C×T F (1,140) = 4.28, p= .04), triglycerides (C×T F (1,141)= 5.03, p=.03), and insulin resistance (C × T F (1, 141) = 4.08, p =.045). In each case, the active drug group showed significant favorable changes over time and the placebo group did not (for waist circumference, −.94 cm, p=.005 for active drug group, +.52 cm, n.s for controls; for glucose, −2.4 mg/dl, p=.03 in active drug group, +1.4 mg/dl, n.s. in controls; for HDL, +2.2 mg/dl, p=.008 in active drug group, −.25 mg/dl, n.s. in controls; for triglycerides, −22.3 mmol/L, p=.03 in active drug group, + 5.8 mmol/L, n.s in controls, for insulin resistance, −.14 units, p=.02 in active drug group, + .03 units, n.s. in controls). See Figure 2 for effect sizes by condition.

Figure 2. Treatment Effects on Metabolic Risk Factors.

Changes in metabolic risk factors as a function of a 2-month experimental intervention (Citalopram vs. Placebo).

There were no significant condition-by-time effects on clinic blood pressure ((F (1, 141) = 1.68 (p=.20) for SBP and 1.17 (p=.28) for DBP), however, there was a marginally significant condition-by-time interaction on laboratory SBP (F (1, 139) = 3.76, (p=.05) (mean change in active drug group, −1.7 mmHg, p = .03, in controls, .68 mmHg, n.s.) and a significant condition-by-time interaction on laboratory DBP (F (1, 139) = 9.83 (p = .0021) as assessed using automated readings (mean change in active drug group, −1.8 mmHg, p=.0004, in controls, .43 mmHg, n.s.) (see Figure 2).

3.4. Hostility and weight as mediators

Hostile Affect changes over the course of the intervention were significantly associated with reductions in blood glucose (F (1, 132) = 8.14 (p=.005). Moreover, the inclusion of Hostile Affect as a time-varying covariate reduced the magnitude of the time-by-condition interaction effect on blood glucose to marginal significance (p=.05, mean change in active drug group, −1.0 mg/dL, p = .43). Hostile Affect changes were unrelated to any of the other metabolic risk factors over the course of the intervention. Using the Assymetric Confidence Limit (ACL) method, we calculated a 95 % confidence range for the indirect or mediating effect of hostility on blood glucose of −1.26- −.06, an effect, in other words, which was statistically significant (p < .05).

Citalopram was associated with a small but significant changes in body mass in this study (CxT F (1, 135) = 12.68, p = .0005). Even after three outliers were removed from the sample2, these significant drug effects remained (C × T F (1, 132) = 9.72, p = .002) (mean changes in active drug group −.26 k/m2, p = .0027, in controls, +.13 k/m2, n.s.).

We examined whether the changes in metabolic risk we observed might have been mediated by these drug-related weight changes. When we included BMI as a time-varying covariate in the models described above (using conservative models in which the three outliers were removed), the relationship between BMI change and risk factor change was significant in each case (for waist, F (1, 123) = 548.01, p < .0001; for glucose, F (1, 131) = 18.36, p < .0001; for HDL, F (1, 130) = 13.74, p = .0003; for triglycerides, F (1, 131) = 19.46, p < .0001; for laboratory DBP, F (1, 128) = 11.75, p = .0008 and for insulin resistance, F (1, 131) = 69.42, p < .0001. Only two of the six condition-by-time interactions (for glucose and DBP) remained significant. Moreover, all of the mediation effects were significant by ACL criteria (p < .05 for laboratory SBP, all other effects p <.01).

We examined whether the mediating effects of hostility on drug-related glucose change were independent of the mediating effects of weight. When we included both hostile affect and BMI as time varying covariates in the model, both of these variables continued to be associated with changes in blood glucose (p = .03 for hostile affect and p = .001 for weight), and the mediating effects of hostility remained significant by ACL criteria (p < .05).

3.5. Drug-related changes in health behaviors

We explored the behavioral factors that might have accounted for the drug-related weight loss. No significant intervention effects were observed on diet, as assessed by the 24 hour dietary recall measure (for our measure of total caloric intake, time-by-condition F (1, 130) = 1.16, n.s.), on physical activity, as assessed by pedometry (for our corrected step count measure, time by condition F ((1, 131) = .68, n.s.), or on quantity of alcohol consumed among drinkers, as assessed by self-report (F (1, 130) = .07, n.s.).

We examined whether any of the observed effects of citalopram on metabolic risk were moderated by gender. When we tested such moderation effects in the models described above, none of the 3-way gender-by-condition-by-time interaction effects were significant, suggesting that, with respect to the effects of citaloporam on metabolic risk factors, men and women responded in a similar manner.

4. Discussion

Our results show that in high hostile healthy adults, citalopram caused small but significant beneficial changes in all of the five NCEP components of the metabolic syndrome, including waist circumference, glucose, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and, by some measures, blood pressure. There was also a drug effect on insulin resistance, as indexed by the homeostatic model (HOMA). Previous studies in smaller samples of diabetic, obese, or metabolically impaired individuals have shown similar salutary effects of short term SSRI administration on metabolic risk. Our results suggest that serotonergic drugs may be associated with short term changes in metabolic risk factors even in samples with no preexisting metabolic abnormalities. Given that the serotonergic intervention was also associated with reductions in hostile affect in this study, the findings are consistent with the possibility that common neurobiological determinants may account, in part, for previously observed associations between hostility and metabolic function.

Moreover, our results are important insofar as they suggest that experimentally induced changes in hostility (in this case, measures of Hostile Affect) may partially mediate salutary effects of citalopram on metabolic risk. The effects were limited to blood glucose; none of the other treatment-related metabolic changes were significantly mediated by hostility in this study.

Weight loss did not appear to account for the association between treatment-related changes in hostility and reductions in blood glucose. Other plausible mechanisms for this association not examined here include possible modulating effects of hostility reduction on sympathetic nervous system or HPA axis pathways: Previous corelational research links hostility with increased sympathoadrenal and HPA axis activity (Pope & Smith, 1991; Suarez, Kuhn, Schanberg, Williams, & AZimmermann, 1998); circulating epinephrine and cortisol, in turn, may enhance glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis (Tonelli, Kishore, Lee, & Hawkins, 2005; Vicini, Avogaro, Spilker, Gallo, & Cobelli, 2002), and lypolysis and the production of nonesterified fatty acids (Bray, 1967; Orth & Williams, 1960; Surwit, et al., 2009), resulting in an increase in fasting glucose levels. Future research is needed examining the mechanisms by which treatment-related reductions in hostility may translate into favorable metabolic effects.

As a mediator of treatment effects, the small weight losses associated with this short term citalopram intervention appeared to have a more widespread influence on metabolic risk than the effects of hostility change per se. All of the metabolic changes observed in this study were significantly mediated by treatment-related changes in body mass index (in most cases, p < .01). We were unable to discern any behavioral mechanisms accounting for weight loss and associated metabolic changes in this study, insofar as there were no detectable effects of the intervention on diet, activity, or alcohol consumption. It is possible that the drug was associated with small direct changes in metabolic activity which drove the weight loss; alternatively, it is possible that the three measures of health behavior used here were not sensitive enough to detect the rather small changes in behavior which would have been necessary to cause the observed alterations in weight.

The finding that weight loss is a robust mediator of the short term metabolic effects of SSRIs is at odds with some of the previous research in this area, which suggested that short term metabolic changes associated with SSRI treatment were independent of weight loss (Breum, et al., 1995; Maheux, et al., 1997); this difference may be attributed to the larger sample used here, with associated increases in power to detect relatively small drug-related changes in weight, or to differences in the populations or treatments involved in these investigations.

An important question about the current metabolic results involves the extent to which they are clinically significant . The effects of the drug on metabolic risk factors did appear to be small (for example, reductions of 2.4 mg/dl were shown in the active treatment group). Of note, the sample was quite healthy at baseline; for example, diabetics were excluded by design, and it is possible that this may have reduced the magnitude of observed effects. Some of the previous studies which reported much larger effects involved Type 2 diabetics-- for example, decreases equivalent to 18 mg/dl were reported among 6 patients randomized to fluoxetine in one study (Maheux, et al., 1997). Other methodological differences between these studies, however (for example, differences in drugs and in effective doses), may also account for these divergent findings.

A second related question concerns the extent to which the effects observed here may be sustained over time. Previous work suggests that the initially observed beneficial effects of SSRIs, such as fluoxetine, on body mass index are transient (Michelson, et al., 1999; Ward, Comer, Haney, Fischman, & Foltin, 1999). Indeed, clinical trials comparing nefazedone with SSRIs have shown that many of the latter agents, although associated with acute decreases in weight, are linked with significant weight gain with long term treatment relative to the comparison group (Sussman, Ginsberg, & Bikoff, 2001). There is even some nonexperimental evidence linking long term use of SSRIs with increased risk for the metabolic syndrome (Raeder, Bjelland, Emil, & Steen, 2006) or for diabetes (Andersohn, Schade, Suissa, & Garbe, 2009), although in both cases, there is some heterogeneity of findings across different agents, with no detectable deleterious metabolic effects associated with use of citalopram per se (Andersohn, et al., 2009; Raeder, et al., 2006). There is some evidence that down regulation of serotonergic autoreceptors with chronic treatment may play a role in the reversal of appetite or weight suppression effects associated with SSRIs (Harvey & Bouwer, 2000). In any case, these results would appear to limit the generalizability of the current set of findings to chronic treatment. Clearly, more remains to be understood about the relationship between SSRI use, body weight, and metabolic risk.

A third question about these data that deserves further investigation involves the implications of these effects for understanding the relationship between hostility and metabolic risk. The present study, as an experimental manipulation of hostility, would seem to present an opportunity to rule out third factor explanations of the previously observed associations between hostility and metabolic risk. The manipulation chosen here, however, appeared to have pleiotropic effects (e.g., weight changes) that were not specific to hostility per se. The relationship between treatment-related changes in hostility and glucose was maintained even after adjusting for drug-related changes in weight. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out that there may have been other effects of the drug that accounted both for changes in hostility and blood glucose. In this light, testing the relationship between hostility and metabolic risk in the context of behaviorally based methods of anger management might be an important means of cross- validating the current study as an experimental test of the effects of hostility on metabolic risk, unconfounded by the impact of other drug-related effects. Such methods might also be expected to exert some longer term positive impact following termination of the intervention.

Of interest, previous behavioral interventions for hostility reduction have been shown to have some effects on physiological measures such as resting blood pressure (Bishop, et al., 2005; Gidron, Davidson, & Bata, 1999), heart rate, and stress-related cardiovascular reactivity (Bishop, et al., 2005). Heart rate variability was shown to be unaffected by such interventions (Sloan, et al., 2010). No other physiological outcomes relevant to metabolic risk have been explored in such studies, to our knowledge. This may be a potentially productive area for future research.

In summary, we have shown that short term pharmacologic enhancement of serotonergic function appears to improve both psychosocial and metabolic markers of cardiovascular risk in a high hostile sample. These results extend the correlational findings linking central serotonergic function, hostility, and metabolic risk to an intervention context, and they have implications for understanding some of the pathways by which hostility may be linked with cardiovascular endpoints. Future research is needed to explore the mechanisms accounting for these results, and the generalizability of these findings, across populations, across time, and across intervention modality.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL040962) and by the Pittsburgh Mind-Body Center (HL076852 [University of Pittsburgh], HL076858 [Carnegie Mellon University]) and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier NCT00217828). The authors are grateful to the individuals who participated in this study. We also thank Barbara Anderson, Mary Witzig, Todd Bear, Melissa Delaney, and Lisa Tamres for their assistance with data collection, and Teresa Steigerwalt, HJ Decker, and Rachel Mackey for their assistance with data management.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

For more information on screening procedures, see (Kamarck, et al., 2009).

Two subjects in the active drug group showed weight losses greater than 3 standard deviations beyond the mean for the group, and one subject in the control group showed weight gains greater than 3 standard deviations beyond the group mean.

Data reduction procedures, factor patterns, and factor scores are identical to those described in the original paper (Kamarck, et al., 2009). The three major factors (Hostile Affect, Hostile Behavior, and Hostile Cognition) were scored based upon unit-weighted averages of the standard (z) scores associated with each of the highly loading component subscales. Because the internal reliabilities of the original BDHI subscales were quite low, these were subjected to an initial data reduction prior to their inclusion in the omnibus model.

Some of these data were presented previously at the 2008 Annual Meeting of the American Psychosomatic Society in Baltimore, Maryland.

Contributions

Author Thomas Kamarck was the Project Leader; he designed the study, wrote the portion of the grant proposal devoted to the study, hired and supervised the staff who carried it out, and wrote the manuscript. Author Matthew Muldoon assisted and advised in the project design and manuscript writing, and provided consultation throughout on medical issues during the participant screening process. Author Stephen Manuck was the Principal Investigator of the Program Project grant of which this project was a part. He helped to design the study and provided consultation on the writing of the grant and manuscript. Author Roger Haskett assisted and advised in the project design and treatment, and protocol and conceptual issues relevant to the use of SSRIs in this population. He was in charge of carrying out the treatment protocol (including supervision of the Research Nurse). Author Jeewon Cheong provided statistical assistance on the project, particularly with respect to the assessment of statistical mediation. Author Janine Flory assisted in the design of the study and helped to oversee the diagnostic interviews associated with the project. Author Elizabeth Vella prepared and presented data from this study relevant to the effects of citalopram on clinic and laboratory blood pressure during her postdoctoral fellowship with the first author.

References

- Andersohn F, Schade R, Suissa S, Garbe E. Long-term use of antidepressants for depressive disorders and the risk of diabetes mellitus. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:591–598. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08071065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barefoot JC, Dodge KA, Peterson BL, Dahlstrom WG, Williams RB. The Cook-Medley hostility scale: Item content and ability to predict survival. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1989;51:46–57. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198901000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop GD, Kaur D, Tan VL, Chua Y, Liew S, Mak K. Effects of a psychosocial skills training workshop on psychophysiological and psychosocial risk in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. American Heart Journal. 2005;150:602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchin MB, Kaplan JR, Manuck SB, Mann JJ. Low versus high prolactin responders to fenfluramine challenge: Marker of behavioral differences in adult male cynomolgus macaques. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;9:93–99. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray GA. Effects of epinephrine, corticotropin, and thyrotropin on lipolysis and glucose oxidation in rat adipose tissue. Journal of Lipid Research. 1967;8:300–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breum L, Bjerre U, Bak JF, Jacobsen S, Astrup A. Long-term effects of fluoxetine on glycemic control in obese patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus or glucose intolerance: Influence on muscle glycogen synthase and insulin receptor kinase activity. Metabolism. 1995;44:1570–1576. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunde J, Suls J. A quantitative analysis of the relationship between the Cook-Medley hostility scale and traditional coronary artery disease risk factors. Health Psychology. 2006;25:493–500. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Durkee A. An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1957;21:343–349. doi: 10.1037/h0046900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Perry M. The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:452–459. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleare AJ, Bond AJ. Does central serotonergic function correlate inversely with aggression? A study using D-fenfluramine in healthy subjects. Psychiatry Research. 1997;69:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(96)03052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF. Central serotonin activity and aggression: Inverse relationship with prolactin response to d-Fenfluramine, but not CSF 5-HIAA concentration, in human subjects. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1430–1435. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.10.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WW, Medley DM. Proposed hostility and pharisaic virtue scales for the MMPI. The Journal of Applied Psychology. 1954;38:414–418. [Google Scholar]

- Daubresse J, Kolanowski J, Krzentowski G, Kutnowski M, Scheen A, Van Gaal L. Usefulness of fluoxetine in obese non-insulin-dependent diabetics: A multicenter study. Obesity Research. 1996;4:391–396. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1996.tb00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson-Rose SA, Lewis TT. Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular diseases. Annual Review of Public Heatlh. 2005;26:469–500. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient edition (SCID-I/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Garg R, Wagener DK, Madans JH. Alcohol consumption and risk of ischemic heart disease in women. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1993;153:1211–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidron Y, Davidson K, Bata I. The short-term effects of a hostility-reduction intervention on male coronary heart disease patients. Health Psychology. 1999;18:416–420. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DS, Fujioka K, Devine W, Bray GA. Fluoxetine treatment of the obese diabetic. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 1992;16:193–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey BH, Bouwer CD. Neuropharmacology of paradoxic weight gain with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Clinical Neuropharmacology. 2000;23:90–97. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200003000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higley JD, King ST, Hasert MF, Champoux M, Suomi SJ, Linnoila DM. Stability of interindividual differences in serotonin function and its relationship to severe aggression and competent social behavior in Rhesus Macaque females. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:67–76. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)80060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higley JD, Mehlman PT, Higley SB, Fernald B, Vickers J, Lindell SG, et al. Excessive mortality in young free-ranging male nonhuman primates with low cerebrospinal fluid 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid concentrations. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:436–441. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830060083011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamarck TW, Haskett RF, Muldoon M, Flory JD, Anderson B, Bies R, et al. Citalopram inervention for hostility: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:174–188. doi: 10.1037/a0014394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: LEA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheux P, Ducros F, Bourque J, Garon J, Chiasson J-L. Fluoxetine improves insulin sensitivity in obese patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus independently of weight loss. International Journal of Obesity. 1997;21:97–102. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuck SB, Flory JD, McCaffery JM, Matthews KA, Mann JJ, Muldoon MF. Aggression, impulsivity and central nervous system serotonergic responsivity in a nonpatient sample. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;19:287–299. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and B-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson D, Amsterdam JD, Quitkin FM, Reimherr FW, Rosenbaum JF, Zajecka J, et al. Changes in weight during a 1-year trial of fluoxetine. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1170–1176. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TQ, Smith TW, Turner CW, Guijarro ML, Hallet AJ. A meta-analytic review of research on hostility and physical health. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:322-248. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon MF, Mackey RH, Korytkowski MT, Flory JD, Pollock BG, Manuck SB. The metabolic syndrome is associated with reduced central serotonergic responsivity in healthy community volunteers. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;91:718–721. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon MF, Mackey RH, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Flory JD, Pollock BG, Manuck SB. Lower central serotonergic responsivity is associated with preclinical carotid artery atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2007;38:2228–2233. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.477638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Kane M, Wiles PG, Wales JK. Fluoxetine in the treatment of obese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetic Medicine. 1994;11:105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1994.tb00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth RD, Williams RH. Response of plasma NEFA levels to epinephrine infusions in normal and obese women. Proceedings of Social and Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1960;104:119–120. doi: 10.3181/00379727-104-25748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perloff D, Grim C, Flack J, Frohlich ED, Hill M, McDonald M, et al. Human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometry. Circulation. 1993;88:2460–2470. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope MK, Smith TW. Cortisol excretion in high and low cynically hostile men. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1991;53:386–392. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter van Loon BJ, Radder JK, Frolich M, Krans HMJ, Zwinderman AH, Meinders AE. Fluoxetine increases insulin action in obese nondiabetic and in obese non-insulin-dependent diabetic individuals. International Journal of Obesity. 1992;16:79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeder MB, Bjelland I, Emil VS, Steen VM. Obesity, dyslipidemia, and diabetes with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: The Hordaland Health Study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:1974–1982. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievert YA, Schakel SF, Buzzard TM. Maintenance of a nutrient database for clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1989;10:416–425. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan RP, Shapiro PA, Gorenstein EE, Tager FA, Monk CE, McKinley PS, et al. Cardiac autonomic control and treatment of hostility: A randomized controlled trial. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72:1–8. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181c8a529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI) Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez EC, Kuhn CM, Schanberg SM, Williams RB, Jr, AZimmermann EA. Neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and emotional responses of hostile men: The role of interpersonal challenge. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1998;60:78–88. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199801000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surwit RS, Lane JE, Millington DS, Zhang H, Feinglos MN, Minda S, et al. Hostility and minimal model of glucose kinetics in African American women. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:646–651. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181acee4c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman N, Ginsberg DL, Bikoff J. Effects of nefazodone on body weight: A pooled analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor- and imipramine-controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62:256–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonelli J, Kishore P, Lee DE, Hawkins M. The regulation of glucose effectiveness: How glucose modulates its own production. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2005;2005:450–456. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000172588.47811.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicini P, Avogaro A, Spilker ME, Gallo A, Cobelli C. Epinephrine effects on insulin-glucose dynamics: The labeled IVGTT two-compartment minimal model approach. American Journal of Physiology, Endocriniology, and Metabolism. 2002;283:E78–E84. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00530.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1487–1495. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward AS, Comer SD, Haney M, Fischman MW, Foltin RW. Fluoxetine-maintained obese humans: Effect on food intake and body weight. Physiology and Behavior. 1999;66:815–821. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RB, Surwit RS, Siegler IC, Ashley-Koch AE, Collins AL, Helms MJ, et al. Central nervous system serotonin and clustering of hostility, psychosocial, metabolic, and cardiovascular endophenotypes in men. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72:601–607. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181eb9d67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]