Abstract

In the populations of Western countries, particular genotypes of the vacuolating cytotoxin gene, vacA (vacA s, signal region variants; vacA m, middle region variants) of Helicobacter pylori are believed to be risk factors for the development of peptic ulcers and gastric cancer. However, it was unclear whether these vacA gene variants are associated with the development of gastrointestinal diseases in developing nations. The relationship between vacA genotypes and H. pylori-related disease development in Latin American and African populations was investigated using meta-analysis of 2612 patients from Latin America (2285 strains) and 520 patients from Africa (434 strains). The frequencies of vacA s and m genotypes differed between strains from Latin America (77.2% for s1 and 68.1% for m1) and Africa (83.9% for s1 and 56.7% for m1). Latin American strains with s1 and m1 genotypes increased the risk of gastric cancer (OR 4.17, 95% CI 2.49–6.98 for s1, and 3.59, 2.27–5.68 for m1) and peptic ulcers (e.g. 1.73, 1.37–2.20 for s1). African strains with the s1 or m1 genotypes also increased the risk of peptic ulcers (8.69, 1.16–64.75 for s1) and gastric cancer (10.18, 2.36–43.84 for m1). The cagA-positive genotype frequently coincided with s1 and m1 genotypes in both populations. Overall, the vacA s and m genotypes were related to gastric cancer and peptic ulcer development and might be useful markers of risk factors for gastrointestinal disease, especially in Latin America. Further studies will be required to evaluate the effects of vacA genotypes in African populations because of the small sample number currently available.

Keywords: Developing country, gastric cancer, Helicobacter pylori, middle region, peptic ulcer, signal region, VacA

Introduction

The gastric mucosa of approximately 50% of the world’s population is infected with Helicobacter pylori, and infection levels exceed 70% of the population in developing areas, such as Latin America and Africa [1–3]. Helicobacter pylori infection is closely associated with the occurrence of peptic ulcers, gastric cancer, and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma [4–6]. However, there are geographical regions where the prevalence of H. pylori infection does not correlate with the incidence of gastric cancer. For example, in Africa, the incidence of gastric cancer is relatively low despite the high prevalence of H. pylori infection (the so-called ‘African enigma’) [7]. Moreover, the incidence of gastric cancer and the associated mortality vary among Latin American countries, with, for example, mortality rates of >20/100 000 in Chile and Costa Rica, and rates of between 10 and 20/100 000 in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela for men [8]. Mexico and Puerto Rico had lower rates of <10/100 000 for men, but these rates were still higher than those in Canada (5.2/100 000) and the USA (3.7/100 000) [8].

Gastric epithelial cell injury is caused by a vacuolating cytotoxin encoded by the vacA gene, which induces host cell vacuolation and eventual cell death [9,10]. The signal (s) region encodes part of the cytotoxin’s signal peptide and N-terminus, while the middle (m) region encodes part of the 55-kDa C-terminal subunit [11]. Two versions of the s-region (s1 and s2) and m-region (m1 and m2) exist, and this causes differences in the vacuolating activities among individual H. pylori strains [11]. The vacA s1 and m1 types can be further subdivided into s1a, s1b and s1c, and m1a, m1b and m1c, respectively [11,12]. The vacA s2 genotype encodes a shorter extension of the N-terminal peptide on the mature protein, which blocks the vacuolating activity [13]. Conversely, infection with vacA s1 strains has been linked to gastric inflammation and duodenal ulceration with enhanced cytotoxin activity [11,13]. In general, the vacA s1m1 strains produce a large amount of toxin with high vacuolating activity in gastric epithelial cells, s1m2 strains produce moderate amounts of toxin, and s2m2 strains produce very little or no toxin [11,13].

Many authors have described the importance of the vacA s and m genotypes for clinical outcomes in Western populations [11,14–20]. In contrast, the importance of the genotypes for clinical outcomes has not been established in Latin American and African populations. Among previous studies investigating vacA genotypes in these countries [15–18,21–51], 21 studies have investigated the relationship between the vacA genotypes and clinical outcomes [18,21–23,25,30,32–38,40,41,43–47,51], and of these only eight [18,25,32,33,36–38,51] and five [18,25,32,33,38] studies have revealed that the vacA s1 and m1 genotypes are linked to an increased risk of gastrointestinal diseases, respectively (Tables 1 and 2). To evaluate whether the vacA genotypes are indeed associated with gastrointestinal diseases in African and Latin American countries, the present study was designed to do a systematic analysis of a sufficiently large sample to generate statistically meaningful data.

TABLE 1.

The vacA s and m genotypes reported in the literature included in the meta-analysis of the Latin American population

| vacA type | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area/country | Authors (Reference no.) |

Year | Diseases | Patients (n) |

Mix (n) |

Not detected (n) |

s (n) |

s1 (n/%) |

s2 (n/%) |

m (n) |

m1 (n/%) |

m2 (n/%) |

| Mexico | Morales-Espinosa R [21] | 1999 | NUD, PU | 20, I | 17S | 7 | 258 | 228 (88.4) | 30 (11.6) | 258 | 222 (86.0) | 3 (14.0) |

| Mexico | Gonzalez-Valencia G [22] | 2000 | NUD, PU | 90, I | 60S | 8 | 134 | 78 (58.2) | 56 (41.8) | 132 | 77 (58.8) | 54 (41.2) |

| Mexico | Garza-Gonzalez E [23] | 2004 | NUD, PU | 50 | 1g | 7 | 42 | 21 (50.0) | 21 (50.0) | 42 | 24 (57.1) | 18 (42.9) |

| Mexico | Chihu L [24] | 2004 | GC | 7 | 0g | 0 | 7 | 7 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 7 | 7 (100) | 0 (0.0) |

| Costa Rica | Con SA [25] | 2007 | NUD, GC | 129 | 7S | 0 | 122 | 97 (79.5) | 25 (20.5) | 122 | 96* (78.7) | 26 (21.3) |

| Colombia | Nogueira C [26] | 2001 | NA | 178 | 8g | 0 | 170 | 157 (92.4) | 13 (7.6) | 170 | 152 (89.4) | 18 (10.6) |

| Colombia | Bravo LE [27] | 2002 | NA | 252 | 19g | 1 | 232 | 208 (89.7) | 24 (10.3) | 232 | 200 (86.2) | 32 (13.8) |

| Colombia | Our data [15,16,28,29] | – | NUD, PU, GC | 227 | 9s | 0 | 218 | 172 (78.9) | 46 (21.1) | 218 | 152* (69.7) | 66 (30.3) |

| Brazil | Evans DG [30] | 1998 | NUD, PU, GC | 56 | 0g | 0 | 56 | 45 (80.4) | 11 (19.6) | 56 | 38 (67.9) | 18 (32.1) |

| Brazil | Mattar R [31] | 2000 | PU | 40 | 17g | 0 | 23 | 21 (91.3) | 2 (8.7) | 23 | 19 (82.6) | 4 (17.4) |

| Brazil | De Gusmao VR [32] | 2000 | NUD, PU | 65 | 10g | 0 | 55 | 40** (72.7) | 15 (27.3) | 54 | 34** (63.0) | 20 (37.0) |

| Brazil | Ashour AA [33] | 2002 | NUD, PU, GC | 82 | 11g | 0 | 71 | 59*,** (83.1) | 12 (16.9) | 71 | 57*,** (80.3) | 14 (19.7) |

| Brazil | Gatti LL [34] | 2003 | NUD, Others | 70 | 9g | 0 | 61 | 43 (70.5) | 18 (29.5) | NA | NA | NA |

| Brazil | Birito CAA [35] | 2003 | NUD, PU | 61 | 0g | 5 | 56 | 43 (76.8) | 13 (23.2) | NA | NA | NA |

| Brazil | Godoy AP [36] | 2003 | NUD, PU | 155 | 17g | 0 | 138 | 86** (62.3) | 52 (37.7) | 138 | 41 (29.7) | 97 (70.3) |

| Brazil | Ribeiro ML [37] | 2003 | NUD, PU | 165 | 28g | 0 | 137 | 94** (68.6) | 43 (31.4) | 137 | 48 (35.0) | 89 (65.0) |

| Brazil | Martins LC [38] | 2005 | NUD, PU | 118 | 4g | 0 | 114 | 94 (82.5) | 20 (17.5) | 114 | 89** (78.1) | 25 (21.9) |

| Brazil | Mattar R [39] | 2005 | PU | 150 | 11g | 71 | 68 | 54 (79.4) | 14 (20.6) | 68 | 45 (66.2) | 23 (33.8) |

| Brazil | Gatti LL [40] | 2006 | NUD, PU | 89 | 12g | 0 | 77 | 57 (74.0) | 20 (26.0) | 77 | 59 (76.6) | 18 (23.4) |

| Brazil | Proenca Modena JL [41] | 2007 | NUD, PU | 99 | 18s | 0 | 81 | 61 (75.3) | 20 (24.7) | 81 | 52 (64.2) | 29 (35.8) |

| Brazil | Our data [16] | – | NA | 16 | 0s | 0 | 16 | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | 16 | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) |

| Venezuela | Ghose C [42] | 2005 | NA | 121, I | 56s | 0 | 65 | 46 (70.8) | 19 (29.2) | 84 | 49 (58.3) | 35 (41.7) |

| Chile | Diaz MI [43] | 2005 | NUD, PU, GC | 79 | NAs | NA | 79 | 72 (91.1) | 7 (8.9) | 79 | 72 (91.1) | 7 (8.9) |

| Argentina | Catalano M [44] | 2001 | NUD, PU | 100 | 3g | 0 | 97 | 62 (63.9) | 35 (36.1) | 97 | 55 (56.7) | 42 (43.3) |

| Argentina | Leanza AG [45] | 2004 | NUD, PU | 88 | 2g | 0 | 86 | 64 (74.4) | 22 (25.6) | 86 | 47 (54.7) | 39 (45.3) |

| Multiple | van Doorn LJ [17] | 1999 | NA | 105 | 25g | 0 | 80 | 75 (93.7) | 5 (6.3) | 80 | 67 (83.8) | 13 (16.2) |

One study by van Doorn LJ [17] included individuals from Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Peru; however, the separate data from each country could not be obtained, and were described as ‘multiple’. ‘Mix’ indicates the number of patients infected with two or more different vacA genotypes. ‘NA’ indicates no data associating Helicobacterpylori disease development and vacA genotypes. ‘g’ indicates the use of gastric biopsy samples, and ‘s’ refers to the use of single colonies. ‘I’ indicates that the study separately analysed each H. pylori genotype when patients were determined to be infected with multiple vacA genotypes. Because each H. pylori strain was analysed as a different vacA genotype [18,22,42,47], patient number and vacA genotype number do not match. A paper reported by Morales-Espinosa [21] was deleted from the meta-analysis of the vacA genotype because there was a possibility of misinterpreting data derived from several mixed strains from the same patients.

GC, gastric cancer; NA, not available; NUD, non-ulcer dyspepsia (gastritis alone without peptic ulcer and gastric cancer); PU, peptic ulcer (gastric ulcer and/or duodenal ulcer).

p <0.05 (significantly increased risk of gastric cancer development) and

p <0.05 (significantly increased risk of peptic ulcer development).

TABLE 2.

The vacA s and m genotypes reported in the literature included in the meta-analysis of the African population

| vacA type | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area/country | Authors (Reference no.) | Year | Diseases | Patients (n) |

Mix (n) |

Not detected (n) |

s (n) |

s1 (n/%) |

s2 (n/%) |

m (n) |

m1 (n/%) |

m2 (n/%) |

| Egypt | van Doorn LJ [17] | 1999 | NA | 33 | 5g | 0 | 28 | 12 (42.9) | 16 (57.1) | 28 | 4 (14.3) | 24 (75.7) |

| Ethiopia | Asrat D [46] | 2004 | NUD, GC | 275 | 17g | 58 | 200 | 177 (88.5) | 23 (11.5) | 200 | 114 (57.0) | 86 (43.0) |

| Nigeria | Smith SI [47] | 2002 | NUD, PU | 41, I | 1g | 0 | 42 | 40 (95.2) | 2 (4.8) | 42 | 10 (23.8) | 32 (76.2) |

| Nigeria | Owen RJ [48] | 2004 | NA | 8 | 0g | 0 | 8 | 8 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 8 | 7 (87.5) | 1 (12.5) |

| South Africa | Kidd M [18,49,50] | 1999, 2001 | NUD, PU. GC | 109, I | 0g | 6 | 103 | 83*,** (80.6) | 20 (19.4) | 103 | 69*,** (67.0) | 34 (33.0) |

| South Africa | Louw JA [51] | 2001 | NUD, GC | 34 | 0g | 0 | 34 | 30* (88.2) | 4 (11.8) | 34 | 27 (79.4) | 7 (20.6) |

| South Africa | Owen RJ [48] | 2004 | NA | 7 | 0g | 1 | 6 | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | 6 | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| South Africa | Yamaoka, Y [16] | 2002 | NA | 13s | 0s | 0 | 13 | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) | 13 | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) |

‘Mix’ indicates the number of patients infected with two or more different vacA genotypes. ‘g’ refers to the use of gastric biopsy samples, and ‘s’ refers to the use of single colonies. When analysing the prevalence of vacA s and m genotypes, we deleted a number of strains with mixed or undetected genotypes. Because most of the three South African studies reported by Kidd et al. [18,49,50] contained overlapping data sets, we selected data from [49] for anlysis of the prevalence of vacA s and m genotypes.

Abbreviations: see Table 1.

p <0.05 (significant increased risk of gastric cancer development) and

p <0.05 (significant increased risk of peptic ulcer development).

Materials and Methods

Study selection

Data from previous studies determining the genotypes of the vacA s- or m-regions in patients infected with H. pylori in Latin American and African populations were included in this study. All eligible studies were identified by searching the PubMed database for manuscripts written in English and published before December 2007 using the following search criteria: ‘vacA’ or ‘vacuolating cytotoxin’ and ‘Helicobacter’ or ‘pylori’ and ‘genotypes’. The references cited in these manuscripts were also screened by the same criteria. Abstracts and manuscripts that did not provide detailed genotype information were excluded.

We conducted a meta-analysis to explore the possible association of the vacA genotypes with the risk of developing gastrointestinal diseases using data from the articles assembled from PubMed along with our data from Colombia. Altogether, the genotypes of 197 Colombian patients were included. Furthermore, we re-examined the vacA genotypes and cagA status of 30 Colombian strains. These strains were derived from large H. pylori stocks at Baylor College of Medicine. Since some of the data for Colombian patients have been used repeatedly in our previous studies [15,16,28,29], we removed all overlapping data.

The clinical population consisted of patients diagnosed with gastric cancer, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, or gastritis alone based on endoscopic and histopathological diagnoses. Gastritis was defined as histological gastritis with no peptic ulcer or gastric cancer. Genotyping of the vacA s- and m-regions, and cagA status, were determined using PCR as described previously [11,52,53].

The total patient group that was analysed was subdivided into the Latin America group (Mexico, Costa Rica, Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Chile and Argentine) and the Africa group (Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria and South Africa).

Data analysis

Whenever possible, patients infected with strains of multiple vacA genotypes were excluded from the meta-analysis. In four papers [18,22,42,47], although the number of patients infected with strains of multiple vacA genotypes was reported, we could not separate the data derived from patients with H. pylori of multiple vacA genotypes from those of patients with H. pylori with a single vacA genotype. In these cases, we included the multiple vacA genotype data in the meta-analysis. Therefore, the total number of patients in the study did not equal the total number of strains analysed. We also excluded patients infected with strains of undetected vacA genotypes. When only one of the s or m genotypes was reported (e.g. s1, with the m genotype unknown), we included the known genotype in the meta-analysis. Therefore, in some cases the total number of s genotypes was not equal to the number of m genotypes (Table 1). Furthermore, some articles analysed did not contain the complete vacA genotyping data [i.e. one or more of vacA s and m genotypes, combinations of s and m genotypes (e.g. s1m1), or s1 subtypes (s1a, s1b and s1c) were missing]; therefore, the total numbers were not identical for each genotype, especially when the data from several different articles were combined (Tables 1 and 2).

Statistical differences in the prevalence of vacA s and m genotypes among the individual countries and ethnic groups were determined by one-way ANOVA or the χ2 test. The effects of vacA s and m genotypes on the risk of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer were expressed as ORs with 95% CIs and with reference to subjects with gastritis alone. All p values were two-sided, and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Included studies

In addition to the studies conducted in our laboratory, 25 studies from Latin America and eight from Africa were identified in PubMed using the above search criteria. However, one study [21] that investigated 258 H. pylori colonies isolated from only 17 Mexican patients was deleted from the meta-analysis. The data from South African patients, reported by Kidd et al. [18,49,50], have been used repeatedly in three studies, of which we selected one [49] to analyse the prevalence of the vacA s and m genotypes, along with another study [18] to analyse the prevalence of the vacA s1 subtypes and their associations with gastroduodenal diseases. Overall, a total of 24 and eight studies were considered for meta-analysis concerning populations of Latin America and Africa, respectively (Tables 1 and 2). We also included our previous studies of Brazilian and South African patients [16], and of Colombian patients [15,16,28,29]. Altogether, we examined 3132 H. pylori-infected patients, including 2612 from Latin America (2285 strains) and 520 from Africa (434 strains) (Tables 1–3).

TABLE 3.

Summary of vacA s and m genotypes reported in different countries

| vacA type | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies (n) |

Patients (n) |

Mix (n) |

Not detected (n) |

s1 (n/%) |

s1a (n/%) |

s1b (n/%) |

s1c (n/%) |

s2 (n/%) |

m1 (n/%) |

m2 (n/%) |

s1m1 (n/%) |

s1m2 (n/%) |

s2m1 (n/%) |

s2m2 (n/%) |

|

| Latin America | |||||||||||||||

| Mexico | 4 | 167 | 78 | 22 | 106 (57.9) | 21 (21.2) | 78 (78.8) | NA | 77 (42.1) | 108 (75.3) | 72 (24.7) | 25 (51.0) | 3 (6.1) | 6 (12.2) | 15 (30.6) |

| Costa Rica | 1 | 129 | 7 | 0 | 97 (79.5) | 0 (0) | 97 (100) | 0 (0) | 25 (20.5) | 96 (78.7) | 26 (21.3) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brazil | 12 | 1166 | 137 | 76 | 705 (74.0) | 20 (6.3) | 298 (93.4) | 1 (0.3) | 248 (26.0) | 488 (58.4) | 347 (41.6) | 475 (57.9) | 136 (16.6) | 7 (0.9) | 202 (24.6) |

| Colombia | 2 | 657 | 36 | 1 | 537 (86.6) | 68 (15.3) | 375 (84.5) | 1 (0.2) | 83 (13.4) | 504 (81.3) | 116 (18.7) | 503 (81.1) | 34 (5.5) | 0 (0) | 83 (13.4) |

| Venezuela | 1 | 121 | 56 | 0 | 46 (70.8) | 0 (0) | 32 (69.6) | 14 (30.3) | 19 (29.2) | 49 (58.3) | 35 (41.7) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Chile | 1 | 79 | NA | 0 | 72 (91.1) | 24 (33.3) | 48 (66.7) | NA | 7 (8.9) | 72 (91.1) | 7 (8.9) | 72 (91.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 7 (8.9) |

| Argentina | 2 | 188 | 5 | 0 | 126 (68.9) | 39 (62.9) | 23 (37.1) | 0 (0) | 57 (31.1) | 102 (55.7) | 81 (44.3) | 101 (55.2) | 25 (13.7) | 1 (0.5) | 56 (30.6) |

| Others | 1 | 105 | 25 | 0 | 75 (93.8) | 0 (0) | 74 (98.7) | 1 (1.3) | 5 (6.2) | 67 (83.8) | 13 (16.3) | 67 (83.8) | 8 (10.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (6.2) |

| Total | 24 | 2612 | 344 | 99 | 1764* (77.2) | 172 (14.2) | 1023 (84.4) | 17 (1.4) | 521 (22.8) | 1486* (68.1) | 697 (31.9) | 1243* (67.8) | 206 (11.3) | 14 (0.8) | 368 (20.1) |

| Africa | |||||||||||||||

| Egypt | 1 | 33 | 5 | 0 | 12 (42.9) | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | 0 (0) | 16 (57.1) | 4 (14.3) | 24 (85.7) | 4 (14.3) | 8 (28.6) | 0 (0) | 16 (57.1) |

| Ethiopia | 1 | 275 | 17 | 58 | 177 (88.5) | NA | NA | NA | 23 (11.5) | 114 (57.0) | 86 (23.0) | 112 (56.0) | 65 (32.5) | 2 (1.0) | 21 (10.5) |

| Nigeria | 2 | 49 | 1 | 0 | 48 (96.0) | NA | NA | NA | 2 (4.0) | 17 (34.0) | 33 (66.0) | 17 (34.0) | 31 (64.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.0) |

| South Africa | 3 | 163 | 0 | 7 | 129 (80.9) | 1 (1.7) | 57 (98.3) | 0 (0) | 27 (19.7) | 111 (70.2) | 45 (29.8) | 70 (63.7) | 18 (16.1) | 3 (3.6) | 18 (16.7) |

| Total | 6 | 520 | 23 | 65 | 366* (83.9) | 8 (11.4) | 62 (88.6) | 0 (0) | 68 (16.1) | 246* (56.7) | 188 (43.3) | 203* (52.5) | 122 (31.5) | 5 (1.3) | 57 (14.7) |

‘Mix’ indicates the number of patients infected with two or more different vacA genotypes. Owen et al. [48] published the data from the Nigeria and South Africa populations. When patients were found to be infected with multiple Helicobacter pylori strains, each H. pylori strain was analysed separately [18,22,42,47]. Therefore, patient number and vacA type number do not match. Moreover, because each study measured a different set of parameters (vacA s and m genotypes), as summarized in Tables 1 and 2, the combined numbers of vacA s and m genotypes and s1 subtypes vary for individual countries.

p <0.05 (significant differences of vacA genotypes among different Latin American or African countries).

NA, not available.

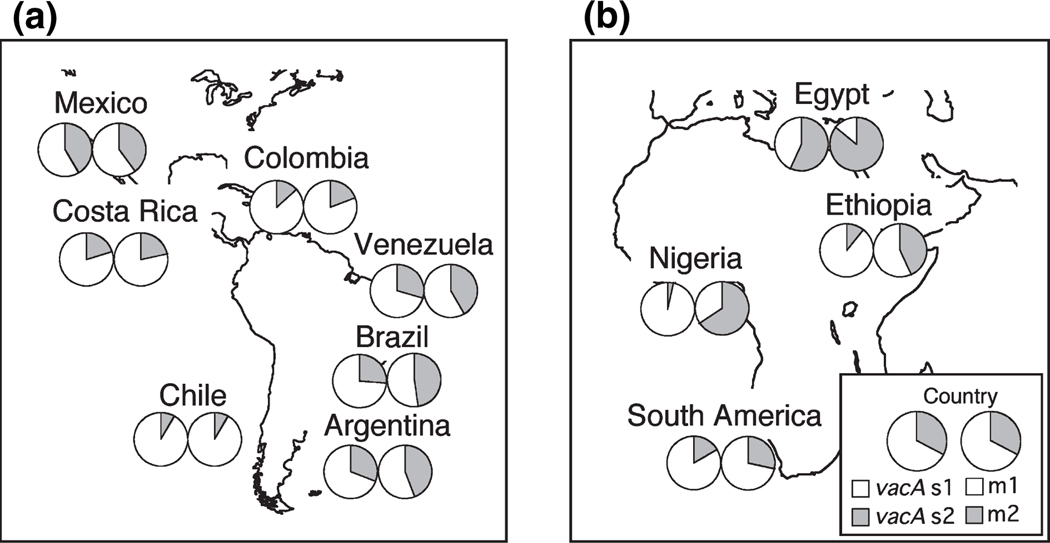

Prevalence of vacA s and m genotypes

Although most of the studies from Africa reported a higher prevalence of the vacA m1 genotype and the vacA s1m1 combination genotype relative to the m2 and s1m2 genotypes (Tables 2 and 3), the frequencies of the m1 and s1m1 genotypes were significantly lower in African strains than in Latin American strains. The prevalence of the vacA s and m genotypes and the vacA s/m combination genotypes also differed significantly among strains from different countries, in both Latin America and Africa (p <0.001) (Table 3 and Fig. 1). The vacA s1b subtype was predominant in strains from all Latin American and African populations with the exception of those from Argentina and Egypt, where the s1a subtype was predominant. The vacA s1c subtype was common only in the Venezuelan strains [21.5% (14/65) of s genotypes in subjects with single-colony infections, and 30.3% (14/46) of the total s1 genotypes], particularly in strains from Amerindian people living in the Amazonian community of Puerto Ayacucho (Piaroas and Guajibos tribes) [77.7% (14/18) and 82.4% (14/17)] [42]. In the Mexican population, the frequency of the vacA s2m1 genotype was on average 12.2%, which is higher than what has been previously reported for other Latin American, African and Western countries (Table 3) [15–17]. The percentage of patients infected with multiple vacA genotypes was very high in Mexico [46.7% (78/167)] and in Venezuela [46.3% (56/121)] compared with other Latin American countries (p <0.05) (Table 3) and developed countries previously studied, e.g. France and Italy (8.8%) [17] and the Netherlands (10.6%) [54].

FIG. 1.

The proportions of vacA s and m genotypes in different Latin American (a) and African (b) populations; the frequencies of vacA s and m genotypes differed among the individual countries of Latin America.

Risk of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer development associated with the vacA s and m genotypes

The vacA s1 genotype was linked to an increased risk of gastric cancer in four of the eight (50.0%) studies [25,33,49,51], and this genotype was also linked to an increased risk of peptic ulcers in five of 19 (26.3%) studies [32,33,36,38,49]. Likewise, the m1 genotype was linked to gastric cancer in three of six (50.0%) studies [25,33,49] and to peptic ulcers in four of 17 (23.5%) studies [32,33,38,49].

In Latin America, the frequency of the vacA s1 genotypes and s1m1 combination genotype in strains isolated from peptic ulcer or gastric cancer patients was significantly higher than from those with gastritis alone (Table 4). Indeed, carrying H. pylori with the vacA s1 or s1m1 genotype significantly increased the risk of peptic ulcer or gastric cancer compared with gastritis alone (Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Summary of vacA s and m genotypes in relation to risk of peptic ulcer and gastric cancer

| Studies (n) |

Patients (n) |

s1 (n/%) |

s1a (n/%) |

s1b (n/%) |

s1c (n/%) |

s2 (n/%) |

m1 (n/%) |

m2 (n/%) |

s1m1 (n/%) |

s1m2 (n/%) |

s2m1 (n/%) |

s2m2 (n/%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin America | |||||||||||||

| Gastritis | 17 | 1161 | 762 (71.3) | 67 (13.3) | 436 (86.5) | 1 (0.2) | 305 (28.7) | 634 (64.2) | 354 (35.8) | 479 (60.2) | 81 (10.1) | 7 (0.9) | 229 (28.8) |

| Peptic ulcer | 16 | 764 | 528* (81.2) | 55 (19.5) | 227 (80.5) | 0 (0) | 122 (18.8) | 404* (65.5) | 213 (34.5) | 359* (65.9) | 100 (18.3) | 1 (0.2) | 85 (15.6) |

| Gastric cancer | 5 | 169 | 177* (91.2) | 24 (25.8) | 68 (73.1) | 1 (1.1) | 17 (8.8) | 148* (86.5) | 23 (13.5) | 124* (84.9) | 6 (4.1) | 0 (0) | 16 (11.0) |

| Africa | |||||||||||||

| Gastritis | 4 | 341 | 234 (85.4) | 1 (4.3) | 22 (95.6) | NA | 40 (14.6) | 151 (57.9) | 123 (42.1) | 112 (56.0) | 65 (32.5) | 2 (1.0) | 21 (10.5) |

| Peptic ulcer | 3 | 30 | 33 (97.1) | 0 (0) | 14 (100) | NA | 1 (2.9) | 15 (44.1) | 19 (55.9) | 5 (25.0) | 14 (70.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.0) |

| Gastric cancer | 3 | 25 | 27 (100) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | NA | 0 (0) | 25* (92.6) | 2 (7.4) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

When patients were found to be infected with multiple vacA genotypes, each Helicobacter pylori strain was analysed separately [18,22,42,47]. Therefore, patient number and genotype number do not match. Moreover, because each study measured a different set of parameters (vacA s and m genotypes), the combined numbers of vacA s and m genotypes and s1 subtypes vary for individual countries.

NA, not available.

p <0.05 (vs. significant prevalence rate of gastritis patients).

TABLE 5.

The risk of gastrointestinal disease development in relation to Helicobacter pylori virulence factors in Latin America and Africa

| Diseases | Factor | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin America | Peptic ulcer | s1 | 1.73 | 1.37–2.20 | <0.01 |

| m1 | 1.06 | 0.86–1.31 | 0.59 | ||

| s1m1 | 2.02 | 1.52–2.68 | <0.01 | ||

| s1m2 | 3.27 | 2.26–4.89 | <0.01 | ||

| Gastric cancer | s1 | 4.17 | 2.49–6.98 | <0.01 | |

| m1 | 3.59 | 2.27–5.68 | <0.01 | ||

| s1m1 | 3.71 | 2.15–6.38 | <0.01 | ||

| s1m2 | 1.06 | 0.40–2.80 | 0.91 | ||

| Africa | Peptic ulcer | s1 | 8.69 | 1.16–64.75 | 0.04 |

| m1 | 0.64 | 0.31–1.32 | 0.23 | ||

| s1m1 | 0.94 | 0.56–8.44 | 0.95 | ||

| s1m2 | 4.52 | 0.56–36.49 | 0.16 | ||

| Gastric cancer | s1 | – | – | – | |

| m1 | 10.18 | 2.36–43.84 | <0.01 | ||

| s1m1 | – | – | – | ||

| s1m2 | – | – | – |

Due to the absence of the vacA s2 allele in gastric cancer patients from the African population, the association of vacA s and s/m combined genotypes with gastrointestinal disease could not be analysed.

In Africa, 100% of patients with gastric cancer carried a vacA s1 strain and >70% of this group carried strains with the m1 genotype. The vacA m1 genotype significantly increased the risk of gastric cancer compared with gastritis alone (OR 10.18) (Table 5). The vacA s1 genotype also significantly increased the risk of peptic ulcer (OR 8.69). However, because the vacA s2 genotype in gastric cancer patients was absent, we could not analyse the association of vacA s and s/m combined genotypes with gastrointestinal diseases.

The association of cagA status and vacA genotypes

The cagA status was strongly associated with the vacA s1 and m1 genotypes (p <0.01) (Table 6). Although there were no significant differences in the frequencies of the vacA s genotypes between the Latin American and African populations, the prevalence of the vacA m1 (63.2%) genotype and s1m1 (62.1%) genotype in cagA-positive patients was lower in Africa than in Latin America (89.1% and 87.7%, respectively) (p <0.01).

TABLE 6.

The association of cagA status with vacA genotypes

| Area | cagA status | s1 (n/%) |

s2 (n/%) |

m1 (n/%) |

m2 (n/%) |

s1m1 (n/%) |

s1m2 (n/%) |

s2m1 (n/%) |

s2m2 (n/%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin America | Positive | 822 (95.2) | 41 (4.8) | 614 (89.1) | 75 (10.9) | 539 (87.7) | 51 (8.3) | 7 (1.1) | 18 (2.9) |

| Negative | 71 (29.1) | 173 (70.9) | 47 (22.9) | 158 (77.1) | 36 (19.8) | 15 (8.2) | 6 (3.3) | 125 (68.7) | |

| Africa | Positive | 205 (91.9) | 18 (8.1) | 110* (63.2) | 64* (36.8) | 108* (62.1) | 53* (30.5) | 2 (1.1) | 11 (6.3) |

| Negative | 26* (42.6) | 35* (57.4) | 5 (18.5) | 22 (81.5) | 5 (18.5) | 12 (44.4) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (37.0) |

p <0.05 (vs. Latin American area).

Discussion

Recently, several studies have consistently shown that the vacA genotype is associated with disease in patients from various countries [18–20,25,32,33,36,38,49,51]. However, most of the articles investigating H. pylori strains from Latin America and Africa have shown no significant relationship between vacA genotypes and gastrointestinal diseases (Table 1). Due to an insufficient amount of data from each individual country in Africa and Latin America, researchers have not been able to draw statistically significant conclusions. Using meta-analysis, we were able to demonstrate that the vacA s1 and m1 genotypes do indeed increase the risk of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer two- to five-times in the populations of these countries. Therefore, we could conclude that the H. pylori virulence factor vacA causes enhanced gastric mucosal inflammation and damage, leading to gastric cancer progression in Latin America, as it does in developed Western countries. In contrast, only ten studies in Africa, including three studies reported by Kidd et al., have investigated the association of the vacA genotype with gastrointestinal diseases, and none of the gastric cancer patients in these studies carried the vacA s2 genotype. This precludes the analysis of the potential association of the vacA genotypes with gastrointestinal diseases in African populations.

Helicobacter pylori isolates from some Latin American populations were predominantly of the vacA s1b subtype. This vacA s1b variant is also more frequent in strains obtained from patients from Portugal and Spain [17,26], two countries that historically had close cultural and economic ties with Latin America. Interestingly, there was a high frequency of the vacA s1c genotype in the Amerindian population of Puerto Ayacucho, Venezuela [42]. We have previously reported that 22% of the strains isolated from Native Colombians had vacA genotypes similar to vacA s1c [16]. These data clearly illustrate a cross link between Native American and East Asian populations, and confirm that H. pylori accompanied humans when they crossed the Bering Strait from Asia to the New World [16].

Gastric cancer is uncommon in Africa, despite high levels of H. pylori infection (the so-called ‘African enigma’) [7]. South African strains with the vacA s1b subtype produce VacA protein with low vacuolating activity on cultured epithelial cells. Moreover, the cagA-positive status coincides less frequently with the toxic vacA s1m1 genotype in African H. pylori strains than in strains isolated from Latin America. It is tempting to speculate that the widespread prevalence of weakly cytotoxic strains (e.g. s1b) may be the reason for the low frequency of H. pylori-associated diseases in African populations. However, the vacA m1 genotype was predominant in African strains and significantly increased the risk of disease development in African gastric cancer patients. Therefore, although gastric carcinogenesis might be influenced by the vacA genotypes, the host’s genetic factors, environmental factors, and other virulence factors of H. pylori should also be important in determining the risk of gastric cancer.

In conclusion, we have shown that the vacA s1 and m1 genotypes increase the risk of developing gastric cancer and peptic ulcers, particularly in the Latin American population, and that the prevalence of specific vacA s and m genotypes varies significantly among the individual countries of the African and South American continents. Genotype testing of vacA s- and m- regions will be useful in screening individuals for risk factors for gastric cancer and peptic ulcer development, not only in Western countries, but in Latin American countries as well.

In contrast, there are currently insufficient data to evaluate the effect of the vacA genotypes in H. pylori-related diseases in African populations. The clinical usefulness of vacA genotyping must be evaluated in future studies of appropriate design using many individuals and several vacA genotypes from Africa.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank O. Gutierrez (Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogota, Colombia) for providing clinical samples from Colombia.

Transparency Declaration

This material is based upon work supported in part by the Office of Research and Development Medical Research Service Department of Veterans Affairs, by Public Health Service grant DK56338 which funds the Texas Medical Center Digestive Diseases Center. The project described was supported by Grant Number DK 62813 from National Institutes of Health (NIH). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Perez-Perez GI, Taylor DN, Bodhidatta L, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infections in Thailand. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:1237–1241. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rocha GA, Queiroz DM, Mendes EN, et al. Indirect immunofluorescence determination of the frequency of anti-H. pylori antibodies in Brazilian blood donors. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1992;25:683–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Souto FJ, Fontes CJ, Rocha GA, de Oliveira AM, Mendes EN, Queiroz DM. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in a rural area of the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1998;93:171–174. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761998000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopkins RJ, Girardi LS, Turney EA. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori eradication and reduced duodenal and gastric ulcer recurrence: a review. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1244–1252. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, de Boni M, Spencer J, Isaacson PG. Antibiotic treatment for low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. Lancet. 1994;343:1503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holcombe C. Helicobacter pylori: the African enigma. Gut. 1992;33:429–431. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.4.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosetti C, Malvezzi M, Chatenoud L, Negri E, Levi F, La Vecchia C. Trends in cancer mortality in the Americas, 1970–2000. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:489–511. doi: 10.1093/humrep/mdi086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leunk RD, Johnson PT, David BC, Kraft WG, Morgan DR. Cytotoxic activity in broth-culture filtrates of Campylobacter pylori. J Med Microbiol. 1988;26:93–99. doi: 10.1099/00222615-26-2-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cover TL, Vaughn SG, Cao P, Blaser MJ. Potentiation of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin activity by nicotine and other weak bases. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1073–1078. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.5.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atherton JC, Cao P, Peek RM, Jr, Tummuru MK, Blaser MJ, Cover TL. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. Association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17771–17777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strobel S, Bereswill S, Balig P, Allgaier P, Sonntag HG, Kist M. Identification and analysis of a new vacA genotype variant of Helicobacter pylori in different patient groups in Germany. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1285–1289. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1285-1289.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Letley DP, Atherton JC. Natural diversity in the n terminus of the mature vacuolating cytotoxin of Helicobacter pylori determines cytotoxin activity. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3278–3280. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3278-3280.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atherton JC, Peek RM, Jr, Tham KT, Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Clinical and pathological importance of heterogeneity in vacA, the vacuolating cytotoxin gene of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:92–99. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamaoka Y, Kodama T, Gutierrez O, Kim JG, Kashima K, Graham DY. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori iceA, cagA, and vacA status and clinical outcome: studies in four different countries. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2274–2279. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2274-2279.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaoka Y, Orito E, Mizokami M, et al. Helicobacter pylori in north and South America before Columbus. FEBS Lett. 2002;517:180–184. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02617-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Doorn LJ, Figueiredo C, Megraud F, et al. Geographic distribution of vacA allelic types of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:823–830. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kidd M, Lastovica AJ, Atherton JC, Louw JA. Heterogeneity in the Helicobacter pylori vacA and cagA genes: association with gastroduodenal disease in South Africa? Gut. 1999;45:499–502. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.4.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miehlke S, Kirsch C, Agha-Amiri K, et al. The Helicobacter pylori vacA s1, m1 genotype and cagA is associated with gastric carcinoma in Germany. Int J Cancer. 2000;87:322–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Figueiredo C, Van Doorn LJ, Nogueira C, et al. Helicobacter pylori genotypes are associated with clinical outcome in Portuguese patients and show a high prevalence of infections with multiple strains. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:128–135. doi: 10.1080/003655201750065861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morales-Espinosa R, Castillo-Rojas G, Gonzalez-Valencia G, et al. Colonization of Mexican patients by multiple Helicobacter pylori strains with different vacA and cagA genotypes. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3001–3004. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.3001-3004.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez-Valencia G, Atherton JC, Munoz O, Dehesa M, la Garza AM, Torres J. Helicobacter pylori vacA and cagA genotypes in Mexican adults and children. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1450–1454. doi: 10.1086/315864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garza-Gonzalez E, Bosques-Padilla FJ, Perez-Perez GI, Flores-Gutierrez JP, Tijerina-Menchaca R. Association of gastric cancer, HLA-DQA1, and infection with Helicobacter pylori cagA+ and vacA+ in a Mexican population. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1138–1142. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chihu L, Ayala G, Mohar A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and characterization of Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from Mexican adults with clinical outcome. J Chemother. 2005;17:270–276. doi: 10.1179/joc.2005.17.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Con SA, Takeuchi H, Valerin AL, et al. Diversity of Helicobacter pylori cagA and vacA genes in Costa Rica: its relationship with atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer. Helicobacter. 2007;12:547–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nogueira C, Figueiredo C, Carneiro F, et al. Helicobacter pylori genotypes may determine gastric histopathology. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:647–654. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64006-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bravo LE, van Doom LJ, Realpe JL, Correa P. Virulence-associated genotypes of Helicobacter pylori: do they explain the African Enigma? Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2839–2842. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamaoka Y, Souchek J, Odenbreit S, et al. Discrimination between cases of duodenal ulcer and gastritis on the basis of putative virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2244–2246. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.6.2244-2246.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamaoka Y, Kikuchi S, el-Zimaity HM, Gutierrez O, Osato MS, Graham DY. Importance of Helicobacter pylori oipA in clinical presentation, gastric inflammation, and mucosal interleukin 8 production. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:414–424. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans DG, Queiroz DM, Mendes EN, Evans DJ., Jr Helicobacter pylori cagA status and s and m alleles of vacA in isolates from individuals with a variety of H. Pylori-associated gastric diseases. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3435–3437. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3435-3437.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mattar R, Laudanna AA. Helicobacter pylori genotyping from positive clotests in patients with duodenal ulcer. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 2000;55:155–160. doi: 10.1590/s0041-87812000000500001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Gusmao VR, Nogueira Mendes E, De Magalhaes Queiroz DM, et al. vacA genotypes in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from children with and without duodenal ulcer in Brazil. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2853–2857. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.8.2853-2857.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashour AA, Magalhaes PP, Mendes EN, et al. Distribution of vacA genotypes in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from Brazilian adult patients with gastritis, duodenal ulcer or gastric carcinoma. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2002;33:173–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2002.tb00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lobo Gatti L, Agostinho Jn F, De Labio R, et al. Helicobacter pylori and cagA and vacA gene status in children from Brazil with chronic gastritis. Clin Exp Med. 2003;3:166–172. doi: 10.1007/s10238-003-0021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brito CA, Silva LM, Juca N, et al. Prevalence of cagA and vacA genes in isolates from patients with Helicobacter pylori-associated gastroduodenal diseases in Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:817–821. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762003000600018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Godoy AP, Ribeiro ML, Benvengo YH, et al. Analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility and virulence factors in Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates. BMC Gastroenterol. 2003;3:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-3-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ribeiro ML, Godoy AP, Benvengo YH, Mendonca S, Pedrazzoli J., Jr Clinical relevance of the cagA, vacA and iceA genotypes of Helicobacter pylori in Brazilian clinical isolates. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;36:181–185. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martins LC, Corvelo TC, Demachki S, et al. Clinical and pathological importance of vacA allele heterogeneity and cagA status in peptic ulcer disease in patients from North Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100:875–881. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762005000800009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mattar R, dos Santos AF, Eisig JN, et al. No correlation of babA2 with vacA and cagA genotypes of Helicobacter pylori and grading of gastritis from peptic ulcer disease patients in Brazil. Helicobacter. 2005;10:601–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2005.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gatti LL, Modena JL, Payao SL, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori cagA, iceA and babA2 alleles in Brazilian patients with upper gastrointestinal diseases. Acta Trop. 2006;100:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Proenca Modena JL, Lopes Sales AI, Olszanski Acrani G, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori genotypes and gastric disorders in relation to the cag pathogenicity island. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;59:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghose C, Perez-Perez GI, van Doorn LJ, Dominguez-Bello MG, Blaser MJ. High frequency of gastric colonization with multiple Helicobacter pylori strains in Venezuelan subjects. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:635–641. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2635-2641.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diaz MI, Valdivia A, Martinez P, et al. Helicobacter pylori vacA s1a and s1b alleles from clinical isolates from different regions of Chile show a distinct geographic distribution. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6366–6372. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i40.6366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Catalano M, Matteo M, Barbolla RE, et al. Helicobacter pylori vacA genotypes, cagA status and ureA-b polymorphism in isolates recovered from an Argentine population. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;41:205–210. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(01)00307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leanza AG, Matteo MJ, Crespo O, Antelo P, Olmos J, Catalano M. Genetic characterisation of Helicobacter pylori isolates from an Argentinean adult population based on cag pathogenicity island right-end motifs, LSPA-glmM polymorphism and iceA and vacA genotypes. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:811–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1198-743X.2004.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asrat D, Nilsson I, Mengistu Y, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori vacA and cagA genotypes in Ethiopian dyspeptic patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2682–2684. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2682-2684.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith SI, Kirsch C, Oyedeji KS, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori vacA, cagA and iceA genotypes in Nigerian patients with duodenal ulcer disease. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51:851–854. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-10-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Owen RJ, Xerry J, Gotada T, Naylor G, Tompkins D. Analysis of geospecific markers for Helicobacter pylori variants in patients from Japan and Nigeria by triple-locus nucleotide sequence typing. Microbiology. 2004;150:151–161. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26467-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kidd M, Lastovica AJ, Atherton JC, Louw JA. Conservation of the cag pathogenicity island is associated with vacA alleles and gastroduodenal disease in South African Helicobacter pylori isolates. Gut. 2001;49:11–17. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kidd M, Atherton JC, Lastovica AJ, Louw JA. Clustering of South African Helicobacter pylori isolates from peptic ulcer disease patients is demonstrated by repetitive extragenic palindromic-PCR fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1833–1839. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.5.1833-1839.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Louw JA, Kidd MS, Kummer AF, Taylor K, Kotze U, Hanslo D. The relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection, the virulence genotypes of the infecting strain and gastric cancer in the African setting. Helicobacter. 2001;6:268–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2001.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamaoka Y, Kodama T, Kashima K, Graham DY, Sepulveda AR. Variants of the 3′ region of the cagA gene in Helicobacter pylori isolates from patients with different H. pylori-associated diseases. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2258–2263. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.8.2258-2263.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kersulyte D, Mukhopadhyay AK, Velapatino B, et al. Differences in genotypes of Helicobacter pylori from different human populations. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3210–3218. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3210-3218.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Doorn LJ, Figueiredo C, Sanna R, et al. Clinical relevance of the cagA, vacA, and iceA status of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:58–66. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]