Abstract

Most women of reproductive age have some physical discomfort or dysphoria in the weeks before menstruation. Symptoms are often mild, but can be severe enough to substantially affect daily activities. About 5–8% of women thus suffer from severe premenstrual syndrome (PMS); most of these women also meet criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). Mood and behavioural symptoms, including irritability, tension, depressed mood, tearfulness, and mood swings, are the most distressing, but somatic complaints, such as breast tenderness and bloating, can also be problematic. We outline theories for the underlying causes of severe PMS, and describe two main methods of treating it: one targeting the hypothalamus-pituitary-ovary axis, and the other targeting brain serotonergic synapses. Fluctuations in gonadal hormone levels trigger the symptoms, and thus interventions that abolish ovarian cyclicity, including long-acting analogues of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) or oestradiol (administered as patches or implants), effectively reduce the symptoms, as can some oral contraceptives. The effectiveness of serotonin reuptake inhibitors, taken throughout the cycle or during luteal phases only, is also well established.

Introduction

Most women of reproductive age have one or more emotional or physical symptom in the premenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle. The symptoms are mild, but 5–8% have moderate to severe symptoms that are associated with substantial distress or functional impairment. In early medical reports about this issue, clinically significant premenstrual symptoms were named premenstrual tension (PMT)1 or premenstrual syndrome (PMS).2 The WHO International Classification of Diseases (ICD) includes “premenstrual tension syndrome” under the heading “Diseases of the Genitourinary Tract”. However, like PMS and PMT, this description is not useful for the purpose of clinical diagnostics, drug labelling, or research, since it is not defined by specific criteria, and does not specify severity.

Diagnosis

In the mid-1980s, a multidisciplinary US National Institutes of Health consensus conference on PMS proposed criteria that were adopted by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual III (DSM III)3 to define the severe form of this condition. Originally entitled “late luteal phase dysphoric disorder”, it was later renamed “premenstrual dysphoric disorder” (PMDD). The diagnosis of PMDD stipulates (1) the presence of at least five luteal-phase symptoms (panel), at least one of which must be a mood symptom (ie, depressed mood, anxiety or tension, affect lability, or persistent anger and irritability); (2) two cycles of daily charting to confirm the timing of symptoms; and (3) evidence of functional impairment. Finally, symptoms must not be the exacerbation of another psychiatric condition.4

A problem with the PMDD diagnosis is that many women with clinically significant premenstrual symptoms do not meet full diagnostic criteria; they might not have a prominent mood symptom or the five different symptoms required as a minimum by DSM IV. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) has attempted to rectify this situation by defining moderate to severe PMS; the criteria are the presence of at least one psychological or physical symptom that causes significant impairment and is confirmed by means of prospective ratings.5

Despite differences between diagnostic systems, women with clinically significant PMS described in scientific reports usually correspond to those with a diagnosis of PMDD. Accordingly, in this Seminar, we use the term PMS to mean severe variants of premenstrual discomfort such as those that would meet the ACOG and most PMDD criteria. It is important to note, however, that some clinicians and researchers question whether all symptoms occurring in the premenstrual phase should be regarded as parts of a single syndrome. This is because although there is general agreement that all symptoms are triggered by fluctuations in sex steroids, and thus abolished when hormonal cyclicity ends, there is no evidence that the symptoms share a common pathophysiological factor, such as an aberration in sex steroid production.

Prevalence

Most studies on the prevalence of premenstrual complaints are based on retrospective reports which, by their nature, can introduce recall bias.6–12 However, the findings of these studies are consistent with those from the few epidemiological studies that used prospective symptom ratings.13,14 Findings of prospective and retrospective studies suggest that 5–8% of women with hormonal cycles have moderate to severe symptoms. However, some studies suggest that up to 20% of all women of fertile age have premenstrual complaints that could be regarded as clinically relevant.15

Pattern of symptom expression

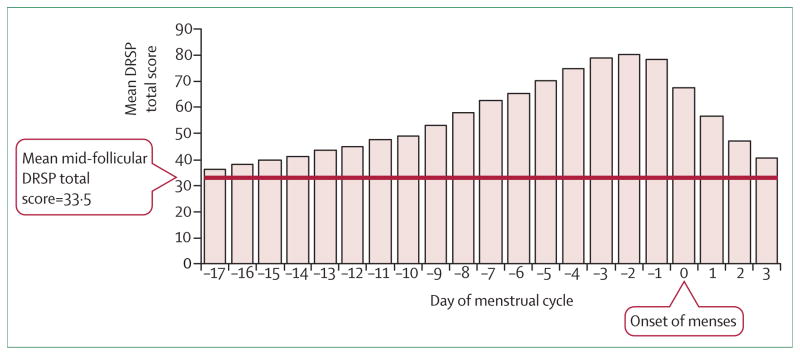

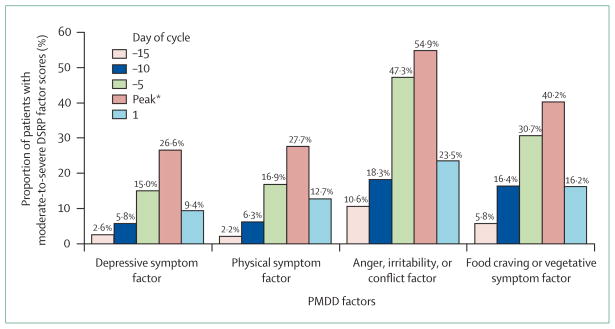

The length of symptom expression varies between a few days and 2 weeks (figure 1). Symptoms often worsen substantially 6 days before, and peak at about 2 days before, menses start.16,17 Anger and irritability are the most severe complaints and start slightly earlier than other symptoms (figure 2).16 It is not uncommon for symptoms to linger into the next menstrual cycle16–18 but, by definition, there must be a symptom-free interval before ovulation. Typically, women have the same set of symptoms from one cycle to the next.19

Figure 1. Timing of PMDD symptom severity across menstrual period.

DRSP=Daily Rating of Severity of Problems. Total symptoms were averaged for the corresponding day of the menstrual cycle. Day 14 indicates the beginning of the luteal phase. Day 1 is the first day of the following menstrual cycle. The follicular phase average score for the entire cohort was 33·5 and is indicated by a horizontal line. Adapted from Pearlstein et al, 2005.16

Figure 2. Severity of PMDD symptoms according to menstrual cycle stage.

DRSP=Daily Rating of Severity of Problems. *The symptom peak occurred on day –2 (ie, 2 days before onset of menses) for depressive symptoms; day –1 for physical symptoms; day –2 for anger, irritability, or tendency towards conflict; day –3 for food cravings. Mean symptom scores for each factor are shown. Adapted from Pearlstein et al, 2005.16

Several patterns of true or apparent comorbidity can occur in a woman with premenstrual symptoms. First, she might have another psychiatric disorder at another point in her life (lifetime comorbidity). Second, she might have an ongoing psychiatric or general medical condition and concurrent premenstrual symptoms that are not part of the co-occurring disorder (concurrent comorbidity). Third, she might have an ongoing psychiatric or general medical condition that becomes worse premenstrually—usually defined as premenstrual exacerbation.4,20

Estimates for lifetime comorbidity between PMS and other mood disorders range from 30% to 70%.12,21–23 This prevalence is higher than one would expect, even taking into consideration that mood disorders are common in women (at least 30% of women have a minor or major depressive disorder at some point in their lives); estimates of comorbidity, however, might be inflated because of an overlap in symptoms. It is notable that the risk of developing perimenopausal depression24 and postnatal depression25,26 has been reported to be higher in women who have PMS, leading some to suggest that these different conditions share a vulnerability to changes in gonadal steroid concentrations.

Anxiety disorders also occur at a higher rate in women with PMS.27,28 Women with PMS, like those with panic disorder (but in contrast to those with other mood disorders), have an increased tendency to panic when exposed to panicogenic agents such as lactate and carbon dioxide, suggesting that panic disorder and PMS share certain pathophysiological mechanisms.27,28

Aetiology and pathophysiology

Since most women of reproductive age report at least mild premenstrual symptoms, a certain degree of discomfort during the luteal phase should probably be considered physiological rather than pathological. In evolutionary terms,29 luteal mood changes could be remnants of the oestrous cycle-related fluctuations in behaviour shown by lower species with the original purpose of promoting reproduction: sexual receptivity being increased and aggression decreased when oestrogen is high before ovulation.30–32 Although aggression in rodents and other animals might not be entirely equivalent to irritability and anger in human beings, such cycle-related variations in behaviour seem likely to be related to cycle-related variations in behaviour in women.

In this context, one should consider the fact that, historically, repeated pregnancies, lactation, or malnourishment led to extended periods of amenorrhoea, a situation that has changed by advances in nutrition and with our capacity to control reproduction.33 The result is that women today have much longer periods of cyclic fluctuations of oestrogen and progesterone with associated premenstrual symptoms. 33

Since the most characteristic feature of PMS is the relation between symptom appearance and menstrual cyclicity, researchers have long suggested that gonadal steroids are involved in the pathophysiology.1 In line with this notion, symptoms are absent during non-ovulatory cycles,34 abolished by ovariectomy35–37 or treatment with ovulation inhibitors,38–41 and reinstated by administration of exogenous hormones.42–45

How changes in sex steroid production provoke luteal symptoms, however, remains to be understood. Many researchers suggest that premenstrual complaints are elicited by the drop in progesterone concentrations in the late luteal phase, and link this to changes in CNS neurotransmitters such as γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA).46,47 This theory is, however, challenged by the fact that many women have symptoms that start at ovulation and during the early luteal phase—ie, before the fall in progesterone has started.

Moreover, for women in whom the endogenous hormonal cyclicity had been abolished by pretreatment with an agonist of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), daily progesterone administration for a month provoked symptoms (with some delay), despite hormone concentrations remaining stable.45 Also, if a luteal decrease in progesterone was the precipitating factor, administration of progesterone during this phase would be an effective treatment, which it is not.48 The alternative hypothesis, that symptoms are triggered by the preovulatory peak in oestradiol, or by the postovulatory increase in progesterone, or both,45,49 thus seems more likely. This theory does not explain, however, why symptoms begin with ovulation for some women but late into the luteal phase for others.

The importance of progesterone compared with oestrogen in triggering symptoms is equally unclear. Mood change reported by postmenopausal women taking sequential hormone replacement therapy suggests that progesterone, rather than oestrogen, is responsible for inducing dysphoria;42,50 moreover, oestrogen exerts an antidepressant effect in women with perimenopausal depression.51 Of note, the days of the cycle during which symptoms are likely to appear are those in which progesterone dominates over oestrogen. On the other hand, oestradiol has been reported to be as effective as gestagen in provoking PMS-like complaints,45 and the oestrogen component of hormone replacement therapy can enhance gestagen-induced dysphoria.52 Moreover, luteal administration of oestrogen has been reported to aggravate premenstrual symptoms,53 and luteal administration of an oestrogen antagonist reduces premenstrual mastalgia.54

Evidence suggests that women with and without PMS do not differ with respect to the production of gonadal steroids,55 indicating that PMS might instead be associated with enhanced responsive ness to normal, fluctuating concentrations of these hormones. In line with this, administration of exogenous gonadal steroids provoked PMS-like symptoms after pretreatment with an ovulation inhibitor in women with PMS, but not in controls.45

Such an enhanced tendency to have disphoria as a reult of the effects of sex steroids on the brain might be heritable, as suggested by twin studies.56–58 Other possible risk factors for PMS are high body-mass index,59 stress,7 and traumatic events.60

With respect to hormones other than the sex steroids, thyroid indices are reported to be more variable in women with PMS than in controls.61,62 Moreover, as in anxiety and mood disorders, changes in circadian rhythms have been noted in PMS. Some studies thus suggest that the absolute levels of hormones such as melatonin, cortisol, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and prolactin are not altered but that the timing of their excretion might be aberrant in women with PMS.63

Central neurotransmission in PMS

Since mood and behavioural symptoms are key features of PMS, underlying mechanisms must involve the brain. Indeed, sex steroids easily pass the blood-brain barrier, and sex steroid receptors are abundant in many brain regions that regulate emotions and behaviour, including the amygdala and the hypothalamus.

The brain neurotransmitter serotonin is implicated in the regulation of mood and behaviour, partly because of observations made in preclinical studies, and partly because of the antidepressant and anxiety-reducing effects exerted by serotonin-facilitating drugs in human beings. This notion has also gained support from genetic studies64,65 and from brain imaging experiments.66

The most clear-cut change in rodents exposed to serotonin depletion is an increase in aspects of behaviour that are dependent on sex steroids—ie, aggression and sexual activity, suggesting that a major physiological role for serotonin is to modulate or dampen sex-steroid-driven behaviour.31,67 Consistent with this, reduced libido is probably the most common side-effect of long-term treatment with serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs).68,69

Sex steroids have been shown to modulate serotonin transmission in rodents70–72 and non-human primates,73 indicating that gonadal hormones influence behaviour partly by interacting with serotonergic transmission. Alternatively, serotonin terminals could exert a dampening influence on brain areas, such as the amygdala, that are under a parallel, independent activating influence of sex steroids.

The importance of serotonin for the regulation of mood and aggression, and the probable role of serotonin in modulating sex-steroid-driven behaviour, suggest that serotonin could be involved in the pathophysiology of PMS. Support for this theory is provided by three sources of evidence. First, premenstrual symptoms are effectively dampened not only by SRIs (see below), but also by other serotonin-enhancing treatments, such as serotonin-releasing agents,74,75 a serotonin precursor,76 and a serotonin-receptor agonist.77 Second, impairment in serotonergic transmission achieved by a tryptophan-free diet,78 or by treatment with a serotonin-receptor antagonist,79 provokes symptoms. Third, various indices of serotonergic trans mission are reported to be aberrant in women with PMS.75,80–89

Another neurotransmitter that has been linked to PMS is the inhibitory aminoacid GABA. This theory gains support from an imaging study,90 the fact that some progesterone metabolites interact with GABA A receptor,46,47 and the observation that women with PMS seem to differ from controls with respect to the responsiveness of this receptor complex.91 To what extent women with PMS have an abnormal production of GABA-A-modulating progesterone metabolites, however, is a matter of controversy,92–94 and whether modulation of GABA A activity can relieve symptoms is unclear.95 Moreover, much of the work implicating GABA in the pathophysiology of PMS is based on the assumption that premenstrual complaints are due to progesterone withdrawal, a notion that has been questioned. Notably, there are important interactions between GABAergic and serotonergic neurons;96,97 a theory implicating GABA in the pathophysiology of PMS is thus not in conflict with the serotonin hypothesis. Further, several SRIs, which have therapeutic benefit for PMS, also have profound effects on enzymes involved in the production of progesterone metabolites that modulate GABA A receptors.98,99

Pathophysiology of somatic symptoms

It remains unclear whether premenstrual somatic symptoms—such as breast tenderness, bloating, and joint and muscle pain—result from reduced tolerance to physical discomfort while in a dysphoric mood state, or are caused by changes in hormone-responsive tissues in the periphery. Studies have failed to confirm fluid retention or breast enlargement in women reporting these symptoms;100,101 moreover, treatment aimed at influencing brain neurotransmission—eg, the SRIs—exerts at least some palliative effect on somatic symptoms. On the other hand, the dopamine D2 receptor agonist, bromocriptine,102,103 or chasteberry,104 which lower serum concentrations of prolactin, are effective for the treatment of premenstrual mastalgia, but not for mood symptoms. Likewise, a specific effect on premenstrual mastalgia could be achieved by luteal administration of danazol105 or an oestrogen-receptor antagonist.54

Results of some early studies suggest the involvement of aldosterone106 or deoxycorticosterone, a progesterone metabolite and aldosterone agonist,33,106 in the pathophysiology of premenstrual bloating. Given that severe abdominal bloating occurs in the absence of weight gain, any theory related to water retention is, however, called into doubt. Many believe that premenstrual headache, migraine, and epilepsy should not be regarded as part of PMS, but as separate conditions. Notably, SRIs have no effect on premenstrual headache. Painful menstrual bleeding (dysmenorrhoea), endometriosis, and menopausal symptoms are often confused with PMS,107 but they are separate and must be clearly distinguished as such in research and in the clinic environment.

Treatment

Before pharmacological treatment is considered, the medical history of women with presumed PMS should be investigated for conditions such as depression, dysthymic disorder, anxiety disorders, and hypothyroidism. Given the possible links between PMS and sexual abuse, as well as with post-traumatic stress disorder,60 a history that assesses the presence of these factors, as well as domestic violence, should be obtained. Some individuals with anxiety and mood disorders, including PMS, attempt to cope with symptoms by using alcohol or illicit drugs, although these substances can provoke or worsen dysphoria and anxiety. Thus, the possible use of such substances should be addressed during the evaluation.

The diagnosis of PMS (according to ACOG criteria) and PMDD requires daily charting of symptoms over two menstrual cycles; various methods have been developed for this purpose, such as the Daily Record of Severity of Problems.108 A woman with severe symptoms, however, might not be willing to accept the delay in treatment involved with such recording. However, the benefit for the patient and the clinician is that it enables a clear diagnostic distinction between PMS/PMDD on the one hand, and premenstrual exacerbation of an underlying psychiatric disorder, or a condition with no relation to the menstrual cycle, on the other.

Many treatment regimens have been touted as effective for PMS, but few are supported by clinical evidence. Since effective treatments do not necessarily reduce all symptoms equally, assessing improvement using summary scales that evaluate change in many symptoms could obscure a specific effect on a particular symptom. Given that some medications might work better for particular symptoms, treatment should be individualised according to the symptom profile.

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs)

Many clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of an SRI for the management of PMS/PMDD have shown benefit,109 the response rate usually being 60–90% for active treatment versus 30–40% for placebo.110 SRIs that have been shown effective are the serotonergic tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine,111,112 the selective SRIs citalopram,113 escitalopram,114 fluoxetine,115–120 paroxetine,121–125 and sertraline,126–130 and the serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine (table).131,132 SRIs reduce both mood symptoms and somatic complaints, and they also improve quality of life and social functioning.122,140,141 Many believe that SRIs should be regarded as first-line treatment in PMS patients with severe mood symptoms.142,143

Table.

Major strategies for treatment of premenstrual syndrome

| Dose | Most important side-effects | |

|---|---|---|

|

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors

| ||

| Clomipramine111,112 | 50–75 mg daily or for half cycle | Dry mouth, sedation, sexual dysfunction, nausea, jitteriness |

| Citalopram113 | 20–40 mg daily or for half cycle | Sexual dysfunction, nausea, jitteriness |

| Escitalopram114 | 10–20 mg daily of for half cycle | Sexual dysfunction, nausea, jitteriness |

| Fluoxetine115–120 | 20–60 mg daily or for half cycle | Sexual dysfunction, nausea, jitteriness |

| Paroxetine121,125 | 20–30 mg daily or for half cycle | Sexual dysfunction, nausea, jitteriness |

| Paroxetine –CR122–124 | 12·5–25·0 mg daily or for half cycle | Sexual dysfunction, nausea, jitteriness |

| Sertraline126–130,133,134 | 50–150 mg daily or for half cycle | Sexual dysfunction, nausea, jitteriness |

| Venlafaxine131,132 | 50–200 mg daily or for half cycle | Sexual dysfunction, nausea, jitteriness |

|

| ||

|

Hormonal interventions

| ||

| Ostradiol transdermally;135 must be combined with oral progestagen intermittently, or intrauterine progestagen | 200 μg oestradiol twice weekly via patch; see references for doses of progestagens | Skin irritation, oral progestagen can cause PMS-like symptoms (which is unlikely with intrauterine progestagen) |

| Oestradiol subcutaneous implant;136 must be combined with oral progestagen intermittently, or intrauterine progestagen | 100 μg subcutaneous implant of oestradiol; see references for doses of progestagens | Mastalgia, PMS-like symptoms from oral progestagen |

| GnRH agonists;38–41 long-term treatment only in rare cases; monitoring of bone density and “add-back” oestrogen is mandatory; oestrogen must be combined with oral progestagen intermittently, intrauterine progestagen, or oral tibolone continuously137 | Depends on which GnRH agonist used: see references; also see references for doses of oestrogen plus progestagens or tibolone | PMS-like symptoms from oral progestagen |

| Drosperinone-ethinyl oestradiol138,139 | 3 mg drosperinone plus 20 μg ethinyl oestradiol for 24 days | Breast pain |

SRIs are more effective for PMS than are anti-depressants that predominantly affect noradrenergic transmission,115,121,133 implying that the effect of SRIs in PMS is not merely an antidepressant effect. This notion is also supported by the fact that the beneficial effect of SRIs for PMS begins rapidly, whereas the antidepressant effect is slow in onset. The fast onset of action in PMS renders intermittent treatment, from midcycle to menses, a feasible alternative to continuous therapy.112,113,119,120,125,127,128,134,144 Data suggest that even briefer periods of active treatment are more effective than placebo.124,145

Clinical experience suggests that most but not all women with PMS prefer intermittent treatment to continuous. SRIs administered intermittently, however, seem less effective for somatic symptoms than for mood symptoms,119,120,125,146 and less effective for somatic symptoms than is continuous treatment.125

Side-effects of SRIs are usually mild. Nausea is very common during the first days of treatment, but vanishes after a few days. It usually does not reappear, even when the treatment is intermittent.125 Reduced libido and anorgasmia are not uncommon, and often persist for the duration of treatment,69 but are not present during the drug-free intervals of intermittent treatment. SRIs are not addictive, but many individuals experience discontinuation symptoms when they stop medication abruptly.16 When SRIs are used intermittently, discontinuation symptoms are seldom a problem, suggesting that 2 weeks is too short an exposure period to elicit withdrawal symptoms.113,117,124

SRIs are approved for PMDD in the USA, Canada, and Australia, but not in Europe. The lack of a European consensus on diagnostic criteria and terminology for PMS/PMDD probably accounts in part for the fact that the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMEA) withdrew the existing licence for fluoxetine in four European countries (including the UK). They argued that there is no sharp borderline between mild PMS and PMDD, and that approval of an SRI for PMDD might lead to unwarranted medication in mild cases. Additionally, they said, PMDD is a condition that could go on for years, and that long-term trials would be needed to assess long-term tolerability. However, these same arguments could be, but have not been, applied to other long-lasting conditions—such as generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia, and dysthymic disorder—for which SRIs are approved in Europe and for which it is equally true that there is no sharp borderline between mild and severe variants.

Other psychoactive drugs

Other CNS-acting drugs tested for use in PMS do not seem to be particularly effective. Whereas lithium147 and non-serotonergic antidepressants121,133,148 have been completely ineffective, the serotonergic 5HT1-A agonist buspirone77,149 exerts weak beneficial effects. For the high-affinity benzodiazepine, alprazolam, efficacy data are conflicting;95,150–152 alprazolam can, however, be a helpful adjunctive treatment for women who identify premenstrual insomnia or overwhelming anxiety as important symptoms. Treatment with alprazolam should be monitored carefully because of the risk of dependence, particularly if the individual has a history of substance abuse.

Hormonal interventions

Given the involvement of sex steroids in the triggering of premenstrual symptoms, many regard treatments that target these hormones as the most rational approach for reducing premenstrual complaints. We emphasise, however, that there is no support for the long-held view that PMS is due to progesterone deficiency; accordingly, attempts to treat PMS by progesterone48 (or with oestrogen53) in the luteal phase have been unsuccessful. Progesterone is nevertheless approved as treatment of PMS in the UK, and is still being used—usually in the form of pessaries—as first-line treatment by many general practitioners.153

The rationale behind the hormonal treatment of PMS is thus not simply to correct a hormonal abnormality, but to interrupt the normal hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal cyclicity that is triggering the symptoms. This can be achieved by administering a long-acting GnRH agonist.38–41 There is persuasive evidence that these preparations are extremely effective. They are, however, relatively invasive since they result in a “medical menopause”, which is accompanied by typical menopausal symptoms, particularly flushing, as well as a risk of osteoporosis if the therapy is prolonged. These side-effects, entirely due to the oestrogen deficiency, can be prevented by oestrogen replacement, combined with a gestagen to prevent oestrogen-induced endometrial hyperplasia (table). Whereas some patients report returning symptoms when given gestagens,44 a meta-analysis suggests that this option is nevertheless often feasible.41 A promising alternative is to combine a GnRH agonist with continuous administration of tibolone, a synthetic oestrogen, progestogen and androgen receptor agonist.41,154

Another way of avoiding gestagen-induced reappearance of symptoms is to administer gestagens locally in the form of a levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine system; systemic hormone concentrations via this route of administration are negligible once the endometrium has become atrophic. Only very limited evidence is available to support this approach, but clinical experience is widespread.

Other methods to inhibit ovarian cyclicity, such as surgical bilateral oophorectomy (which can be undertaken laparoscopically), also abolish PMS.35,36,155 As with treatment with long-acting GnRH agonists, oophorectomy requires hormonal add-back with oestrogen plus gestagens. If bilateral oophorectomy and hysterectomy are combined, oestrogen can be used alone. Surgical therapy tends to be too invasive an approach for most patients with PMS. However, patients who have a separate gynaecological disorder requiring hysterectomy usually must consider removal or conservation of the ovaries. Conservation of the ovaries is nearly always advised in younger women—however, if a patient has debilitating PMS, conservation of the ovaries might be inadvisable, and the patient could request that her ovaries are removed. Although no research evidence is available to support this, administration of a GnRH agonist for 2–3 months before surgery will show the patient the probable effect of removing the ovaries and could inform her decision.

Administration of oestrogen at doses that inhibit ovulation135,137 is one of the simplest ways to effectively abolish PMS symptoms. Oral therapy is not usually advised; instead oestrogen administered as a transdermal patch135 or subcutaneous implant136,156 has been recommended (table). Doses are usually higher than are those required for hormone replacement treatment, but lower than for the oral contraceptive pill; for patches, 100, 150, or 200 μg could be necessary. Unless the patient has had a hysterectomy, she will need to be given a progestagen to prevent endometrial hyperplasia. This could result in restimulation of PMS in some patients, unless it is administered within a progesterone-containing levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine system. Although there is clear-cut evidence that oestrogen suppresses both ovulation and symptoms, and there is good evidence that the intrauterine system prevents hyperplasia, evidence for the use of this combination as treatment for PMS is limited.157,158

Many clinicians use oral contraceptives to manage PMS, but placebo-controlled studies have been few and mostly negative.159,160 Since women taking oral contraceptives might have more hormone-related symptoms during the 7-day hormone-free interval than during hormone ingestion,161 and since shortening of the hormone-free interval reduces such complaints,162 oral contraceptives with few hormone-free days might also be of value for PMS. In line with this, studies show efficacy of a novel oral contraceptive with a hormone-free interval of 4 rather than 7 days.138,139 In part, the therapeutic benefit of this oral contraceptive, however, could be a result of the gestagen component, drospirenone, exerting anti-aldosterone and antiandrogen effects.

The synthetic androgen and gonadotropin inhibitor danazol, when administered at doses that block ovulation, is effective for PMS;163–165 however, hirsutism and risk of teratogenicity preclude its use as a first-line agent. Danazol administered at low doses in the luteal phase of the cycle only is not effective for the general symptoms of PMS but for the management of mastalgia and with minimal side-effects.105 Luteal administration of an oestrogen receptor antagonist54 also reduces mastalgia.

Other treatments

Possible alterations in circadian rhythmicity63 suggest that bright light treatment might be effective for moderate to severe PMS. One controlled study166 suggests benefit for this intervention, but it is not clear how long the possible therapeutic effects persist.

The aldosterone antagonist spironolactone seems to be effective for symptoms of bloating and breast pain in PMS,106,167,168 although the link between premenstrual somatic symptoms and water retention is questionable.

Most studies assessing the therapeutic effect of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) in PMS had several methodological limitations, including lack of prospective ratings. Definitive conclusions regarding efficacy cannot be drawn, but a quantitative review suggested that B6 has benefit over placebo.169 Calcium supplements could be helpful for women with PMS,135 as could Vitex agnus-castus (chasteberry), which is claimed to have antiprolactin effects.170 The use of evening primrose oil has been popularised but seems to be ineffective.171 Several studies have assessed the therapeutic benefit of magnesium treatment and some,172 but not all,173 have found it effective. However, these studies have been small and are not definitive; moreover, magnesium can be poorly tolerated.

Although books and magazine articles for the lay public have touted the benefit of restricting sugar and eating multiple small meals as management of PMS, there is little support for these strategies. On the other hand, studies of diets that increase the relative intake of complex carbohydrates suggest benefit, which might be due to an enhanced transport of the serotonin precursor tryptophan into the brain, leading to a transient increase in the synthesis of this transmitter.174,175 Cognitive behavioural therapy176 and exercise177 have also has been claimed to be beneficial.

Various other treatments have been assessed in PMS, but cannot yet be regarded as evidence-based because the studies were not controlled, were flawed, or their findings not replicated. The non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications mefenamic acid178 and naproxen,179 as well as the opioid receptor blocker naltrexone180 are among these.

Conclusions

There is substantial empirical research to support the existence of a severe premenstrual disorder causing marked functional impairment. Severe PMS is consistently reported by about 5% of all women of fertile age. The management of PMS is complex. At the outset it is important to establish a precise diagnosis and not rely on the patient’s own diagnosis. It is mandatory to separate PMS/PMDD from other diagnoses, particularly depression and anxiety disorders, premenstrual exacerbation of another disorder, or mild physiological symptoms requiring no more than reassurance; preferably this assessment should be done by the general practitioner before referral to a gynaecologist or a psychiatrist. Diagnosis is best achieved through daily rating symptoms over at least one menstrual cycle; clinicians can ask patients to choose their worst symptoms and chart the severity daily, or can select a validated scale such as the Daily Record of Severity of Problems. The disappearance of symptoms after menstruation is the key to diagnosis. PMS does not seem to be due to abnormal concentrations of sex steroids, but the symptoms are triggered by fluctuations of such hormones, the difference between patients and controls probably being that patients are more sensitive to such fluctuations. With respect to brain function, the transmitters serotonin and GABA have been implicated in the underlying mechanism. Treatments inhibiting ovulation, such as GnRH analogues, oestrogen, and certain new oral contraceptives, effectively reduce the symptoms, as do treatment with SRIs, which by some institutions are regarded as first-line agents in severely affected patients.

Search strategy and selection criteria.

In this Seminar, we searched Medline (1950–2006) with the subject heading “premenstrual syndrome” and keywords of “premenstrual syndrome” and “premenstrual dysphoric disorder”. Of the 3138 publications that we identified, we selected the most up-to-date publications as well as key reports in the field relevant to the phenomenology, pathophysiology, and treatment of moderate to severe PMS and PMDD. To ensure that important publications were reviewed, we searched the reference lists of articles as well as reviews. We incorporated additional publications after comments from peer reviewers.

Panel: Clinical criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

-

In most menstrual cycles during the past year, at least five of the following symptoms should have been present for most of the last week of the luteal phase, remitted within a few days after onset of menses, and remained absent in the week after menses. At least one symptom must be 1, 2, 3, or 4:

Depressed mood or dysphoria

Anxiety or tension

Affect lability

Irritability

Decreased interest in usual activities

Concentration difficulties

Marked lack of energy

Marked change in appetite, overeating, or food cravings

Hypersomnia or insomnia

Feeling overwhelmed

Other physical symptoms—eg, breast tenderness, bloating

Symptoms markedly interfere with work, school, social activities, or relationships

Symptoms are not just an exacerbation of another disorder

The first three criteria must be confirmed by prospective daily ratings for at least two consecutive menstrual cycles

Adapted from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV (DSM IV).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Between 2004 and 2006, KAY provided a consultation to Wyeth and Berlex; received honoraria from Wyeth and Berlex that was less than $10 000 annually; received grants from Berlex, Wyeth, and medication to support a small study from GlaxoSmithKline and from Pfizer; grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Association for Research in Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders, and the Federal Health Resources Services Administration; received an honorarium in 2007 for a lecture from Berlex; and receives continued grants from Wyeth (ongoing since 2006) and from the National Institutes of Health and the National Association for Research in Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders. Between 2004 and 2007, PMSO’B provided consultations to Bayer Schering and TAP Pharmaceuticals; received research grants from Bayer Schering, Wyeth, GlaxoSmithKline, Beecham, and Lilly; received honoraria from Bayer Schering totally less than £5000; and received grants from the British Heart Foundation and North Staffordshire Medical Institute. EE has received research grants from Lundbeck and Bristol Myers Squibb, and has provided consultations to Schering, Lundbeck, and Lilly.

Contributor Information

Kimberly Ann Yonkers, Departments of Psychiatry, Epidemiology and Public Health and Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Science, Yale School of Medicine, CT, USA.

Prof. P M Shaughn O’Brien, Keele University Medical School, University Hospital of North Staffordshire, Stoke on Trent, UK.

Prof. Elias Eriksson, Department of Pharmacology, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, Sahlgrenska Academy, Göteborg University, Sweden.

References

- 1.Frank R. The hormonal causes of premenstrual tension. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1931;26:1053–57. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greene R, Dalton K. The premenstrual syndrome. BMJ. 1953;1:1007–14. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4818.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-DSM-III. 3. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-DSM-IV. 4. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.ACOG. ACOG practice bulletin: premenstrual syndrome. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2001;73:183–91. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson SR, McChesney C, Bean JA. Epidemiology of premenstrual symptoms in a nonclinical sample—I: Prevalence, natural history and help-seeking behavior. J Repro Med. 1988;33:340–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deuster P, Adera T, South-Paul J. Biological, social, and behavioral factors associated with premenstrual syndrome. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:122–28. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramacharan S, Love EJ, Fick GH, Goldfien A. The epidemiology of premenstrual symptoms in a population based sample of 2650 urban women. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:377–81. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90039-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woods NF, Most A, Dery GK. Prevalence of perimenstrual symptoms. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:1257–64. doi: 10.2105/ajph.72.11.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersch B, Wendestam C, Hahn L, Ohman R. Premenstrual complaints. Prevalence of premenstrual symptoms in a Swedish urban population. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;5:39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angst J, Sellaro R, Merikangas KR, Endicott J. The epidemiology of perimenstrual psychological symptoms. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104:110–16. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wittchen H, Becker E, Lieb R, Krause P. Prevalence, incidence and stability of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the community. Psychol Med. 2002;32:119–132. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivera-Tovar AD, Frank E. Late luteal phase dysphoric disorder in young women. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1634–36. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.12.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soares C, Cohen L, Otto M, Harlow B. Characteristics of women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) who did or did not report history of depression: a preliminary report from the Harvard study of moods and cycles. J Women’s Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:873–78. doi: 10.1089/152460901753285778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borenstein J, Dean B, Endicott J, et al. Heath and economic impact of the premenstrual syndrome. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:515–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearlstein T, Yonkers K, Fayyad R, Gillespie J. Pretreatment pattern of symptom expression in premenstrual dsyphoric disorder. J Affect Disord. 2005;85:275–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meaden PM, Hartlage SA, Cook-Kerr J. Timing and severity of symptoms associated with the menstrual cycle in a community-based sample in the Midwestern United States. Psychiatr Res. 2005;134:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sternfeld B, Swindle R, Chawla A, Long S, Kennedy S. Severity of premenstrual symptoms in a health maintenance organization population. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:1014–24. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)01958-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. Premenstrual syndrome: Evidence for symptom stability across cycles. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1741–46. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.12.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steiner M, Born L. Diagnosis and treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: an update. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;15 (suppl 3):S5–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearlstein TB, Frank E, Rivera-Tovar A, Thoft JS, Jacobs E, Mieczkowski TA. Prevalence of axis I and axis II disorders in women with late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. J Affect Disord. 1990;20:129–34. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(90)90126-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halbreich U, Endicott J. Relationship of dysphoric premenstrual changes to depressive disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1985;71:331–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1985.tb02532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mackenzie TB, Wilcox K, Baron H. Lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in women with perimenstrual difficulties. J Affect Disord. 1986;10:15–19. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(86)90044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richards M, Rubinow DR, Daly RC, Schmidt PJ. Premenstrual symptoms and perimenopausal depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:133–37. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Studd JWW, Smith RNJ. Estrogens and depression in women. Menopause: J North Am Menopause Soc. 1994;1:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, Murphy J, Nieman L, Rubinow DR. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:924–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landen M, Eriksson E. How does premenstrual dysphoric disorder relate to depression and anxiety disorders? Depress Anxiety. 2003;17:122–29. doi: 10.1002/da.10089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yonkers KA. Anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders: How are they related to premenstrual disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:62–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosseinsky DR, Debonnel PG. An evolutionary theory of premenstrual tension. Lancet. 1974;2:1024. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)92132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rapkin AJ, Pollack DB, Raleigh MJ, Stone B, McGuire MT. Menstrual cycle and social behavior in vervet monkeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20:289–97. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)00060-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho H-P, Olsson M, Westberg L, Melke J, Eriksson E. The serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine reduces sex steroid-related aggression in female rats: an animal model of premenstrual irritability? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:502–10. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hyde J, Sawyer TF. Estrous cycle fluctuations in aggressiveness of house mice. Horm Behav. 1977;9:290–95. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(77)90064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacDonald PC, Dombroski RA, Casey ML. Recurrent secretion of progesterone in large amounts: An endocrine/metabolic disorder unique to young women? Endocrine Rev. 1991;12:372–401. doi: 10.1210/edrv-12-4-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammarback S, Ekholm U-B, Backstrom T. Spontaneous anovulation causing disappearance of cyclical symptoms in women with the premenstrual syndrome. Acta Endocrinologica. 1991;125:132–37. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1250132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casper RF, Hearn MT. The effect of hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy in women with severe premenstrual syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:105–09. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90831-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casson P, Hahn PM, Van Vugt DA, Reid RL. Lasting response to ovariectomy in severe intractable premenstrual syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90830-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cronje WH, Vashisht A, Studd JWW. Hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy for severe premenstrual syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2152–55. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muse KN, Cetel NS, Futterman LA, Yen SSC. The premenstrual syndrome: Effects of “medical ovariectomy”. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1345–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198411223112104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bancroft J, Boyle H, Warner P, Fraser HM. The use of an LHRH agonist, buserelin, in the long-term management of premenstrual syndromes. Clin Endocrinol. 1987;27:171–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1987.tb01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hammarback S, Backstrom T. Induced anovulation as treatment of premenstrual tension syndrome: a double-blind cross-over study with GnRH-agonist versus placebo. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1988;67:159–66. doi: 10.3109/00016348809004191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Ismail KMK, Jones PW, O’Brien PMS. The effectiveness of GnRHa with and without ‘add-back’ therapy in treating premenstrual syndrome: a meta analysis. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;111:585–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Magos AL, Brewster E, Singh R, O’Dowd T, Brincat M, Studd JWW. The effects of norethisterone in postmenopausal women on oestrogen replacement therapy: a model for the premenstrual syndrom. BJOG. 1986;93:1290–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1986.tb07868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henshaw C, Foreman D, Belcher J, Cox J, O’Brien S. Can one induce premenstrual symptomatology in women with prior hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy? J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 1996;17:21–28. doi: 10.3109/01674829609025660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leather AT, Studd JW, Watson NR, Holland EF. The treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome with goserelin with and without “add-back” estrogen therapy: a placebo-controlled study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1999;13:48–55. doi: 10.1080/09513599909167531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt PJ, Nieman LK, Danaceau MA, Adams LF, Rubinow DR. Differential behavioral effects of gonadal steriods in women with and in those without premenstrual syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:209–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801223380401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith SS, Ruderman Y, Frye C, Homanics G, Yuan M. Steroid withdrawal in the mouse results in anxiogenic effects of 3alpha, 5beta-THP: a possible model of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Psychopharmacology. 2005;29:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0168-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sundstrom Poromaa I, Smith S, Gulinello M. GABA receptors, progesterone and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Arch Women Ment Health. 2003;6:23–41. doi: 10.1007/s00737-002-0147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wyatt K, Dimmock P, Jones P, Obhrai M, O’Brien S. Efficacy of progesterone and progestogens in management of premenstrual syndrome: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;323:776–81. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt PJ, Nieman LK, Grover GN, Muller KL, Merriam GR, Rubinow DR. Lack of effect of induced menses on symptoms in women with premenstrual syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1174–79. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104253241705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hammarback S, Backstrom T, Holst J, von Schoultz B, Lyrenas S. Cyclical mood changes as in the premesntrual tension syndrome during sequential estrogen-progestagen posmenopausal replacement therapy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1985;64:393–97. doi: 10.3109/00016348509155154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmidt PJ. Depression, the perimenopause, and estrogen therapy. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1052:27–40. doi: 10.1196/annals.1347.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bjorn I, Sundstrom-Poromaa I, Bixo M, Nyberg S, Backstrom G, Backstrom T. Increase of estrogen dose deteriorates mood during progestin phase in sequential hormonal therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2026–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dhar V, Murphy BEP. Double-blind randomized crossover trial of luteal phase estrogens (Premarin) in the premenstrual syndrome (PMS) Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1991;15:489–93. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(90)90072-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oksa S, Luukkaala T, Maenpaa J. Toremifene for premenstrual mastalgia: a randomised, placebo-controlled crossover study. BJOG. 2006;113:713–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rubinow D, Schmidt P. The neuroendocrinology of menstrual cycle mood disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;771:648–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Condon JT. The premenstrual syndrome: A twin study. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:481–86. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.4.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Corey LA, Neale MC. Longitudinal population-based twin study of retrospectively reported premenstrual symptoms and lifetime major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1234–40. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.9.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Treloar S, Heath A, Martin N. Genetic and environmental influences on premenstrual symptoms in an Australian twin sample. Psychol Med. 2002;32:25–38. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Masho SW, Adera T, South-Paul J. Obesity as a risk factor for premenstrual syndrome. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;26:33–39. doi: 10.1080/01443610400023049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perkonigg A, Yonkers K, Pfister H, Lieb R, Wittchen HU. Risk factors for premenstrual dysphoric disorder in a community sample of young women: The role of traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1314–22. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Girdler SS, Pedersen CA, Light KC. Thyroid axis function during the menstrual cycle in women with premenstrual syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 1995;20:395–403. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schmidt PJ, Grover GN, Roy-Byrne PP, et al. Thyroid function in women with premenstrual syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:671–74. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.3.8445024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parry BL, Newton RP. Chronobiological basis of female-specific mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25 (suppl 5):S102–08. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, et al. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala. Science. 2002;297:400–03. doi: 10.1126/science.1071829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–89. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parsey RV, Hastings RS, Oquendo MA, et al. Lower serotonin transporter binding potential in the human brain during major depressive episodes. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:52–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eriksson E, Andersch B, Ho HP, Landen M, Sundblad C. Diagnosis and treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63 (suppl 7):16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gregorian RS, Golden KA, Bahce A, Goodman C, Kwong WJ, Khan ZM. Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1577–89. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sundblad C, Wikander I, Andersch B, Eriksson E. A naturalistic study of paroxetine in premenstrual syndrome: efficacy and side effects during ten cycles of treatment. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;7:201–06. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(97)00404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carlsson M, Carlsson A. A regional study of sex differences in rat brain serotonin. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1988;12:53–61. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(88)90061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hiroi R, McDevitt RA, Neumaier JF. Estrogen selectively increases tryptophan hydroxylase-2 mRNA expression in distinct subregions of rat midbrain raphe nucleus: association between gene expression and anxiety behavior in the open field. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:288–95. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ, Roca CA. Estrogen-serotonin interactions: implications for affective regulation. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:839–50. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bethea CL, Lu NZ, Gundlah C, Streicher JM. Diverse actions of ovarian steroids in the serotonin neural system. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2002;23:41–100. doi: 10.1006/frne.2001.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brzezinski AA, Wurtman JJ, Wurtman RJ, Gleason R, Greenfield J, Nader T. d-fenfluramine suppresses the increased calorie and carbohydrate intakes and improves the mood of women with premenstrual depression. J Am Coll Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:296–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Su T-P, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, Murphy DL, Rubinow DR. Effect of menstrual cycle phase on neuroendocrine and behavioral responses to the serotonin agonist m-chlorophenylpiperazine in women with premenstrual syndrome and controls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1220–28. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.4.3905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Steinberg S, Annable L, Young S, Liyanage N. A placebo-controlled clinical trial of L-tryptophan in premenstrual dysphoria. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:313–20. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Landen M, Eriksson O, Sundblad C, Andersch B, Naessen T, Eriksson E. Compounds with affinity for serotonergic receptors in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria: a comparison of buspirone, nefazodone and placebo. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155:292–98. doi: 10.1007/s002130100718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Menkes DB, Coates DC, Fawcett JP. Acute tryptophan depletion aggravates premenstrual syndrome. J Affect Disord. 1994;32:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roca C, Schmidt P, Smith M, Danaceau M, Murphy D, Rubinow D. Effects of metergoline on symptoms in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1876–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bancroft J, Cook A, Davidson D, Bennie J, Goodwin G. Blunting of neuroendocrine responses to infusion of L-tryptophan in women with perimenstrual mood change. Psychol Med. 1991;21:305–12. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700020407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eriksson O, Wall A, Marteinsdottir I, et al. Mood changes correlate to changes in brain serotonin precursor trapping in women with premenstrual dysphoria. Psychiatry Res. 2006;146:107–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fitzgerald M, Malone KM, Li S, et al. Blunted serotonergic response to fenfluramine challenge in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:556–58. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Halbreich U, Tworek H. Altered serotonergic activity in women with dysphoric premenstrual syndromes. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1993;23:1–27. doi: 10.2190/J2W0-RTGD-NYKK-FF77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rojansky N, Halbreich U, Zander K, Barkai A, Goldstein S. Imipramine receptor binding and serotonin uptake in platelets of women with premenstrual changes. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 1991;31:146–52. doi: 10.1159/000293135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Steege JF, Stout AL, Knight BS, Nemeroff CB. Reduced platelet tritium-labeled imipramine binding sites in women with premenstrual syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:168–72. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91653-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rasgon N, McGuire M, Tanavoli S, Fairbanks L, Rapkin A. Neuroendocrine response to an intravenous L-tryptophan challenge in women with premenstrual syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:144–49. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00452-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Steiner M, LNY, Coote M, Wilkins A, Lepage P. Serotonergic dysfunction in women with pure premenstrual dysphoric disorder: is the fenfluramine challenge test still relevant. Psychiatry Res. 1999;87:107–15. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yatham L, Barry S, Dinan TG. Serotonin receptors, buspirone, and premenstrual syndrome. Lancet. 1989;1:1447–48. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Melke J, Westberg L, Landen M, et al. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms and platelet [3H] paroxetine binding in premenstrual dysphoria. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:446–58. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Epperson CN, Haga K, Mason GF, et al. Cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid levels across the menstrual cycle in healthy women and those with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:851–58. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sundstrom I, Ashbrook D, Backstrom T. Reduced benzodiazepine sensitivity in patients with premenstrual syndrome: a pilot study. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 1997;22:25–38. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(96)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schmidt PJ, Purdy RH, Moore PH, Paul SM, Rubinow DR. Circulating levels of anxiolytic steroids in the luteal phase in women with premenstrual syndrome and in control subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:1256–60. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.5.7962316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rapkin AJ, Morgan M, Goldman L, Brann DW, Simone D, Mahesh VB. Progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:709–14. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Girdler S, Straneva P, Light K, Pederson C, Morrow A. Allopregnanolone levels and reactivity to mental stress in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:788–97. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schmidt PJ, Grover GN, Rubinow DR. Alprazolam in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:467–73. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820180069007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bhagwagar Z, Wylezinska M, Taylor M, Jezzard P, Matthews PM, Cowen PJ. Increased brain GABA concentrations following acute administration of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:368–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sundstrom I, Backstrom T. Citalopram increases pregnanolone sensitivity in patients with premenstrual syndrome: an open trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:73–88. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A. Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine stereospecifically and selectively increase brain neurosteroid content at doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;186:362–72. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Griffin LD, Mellon SH. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors directly alter activity of neurosteroidogenic enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(13):512–17. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Faratian B, Gaspar A, O’Brien PM, Johnson IR, Filshie GM, Prescott P. Premenstrual syndrome: weight, abdominal swelling, and perceived body image. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;150:200–04. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(84)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Andersch B, Hahn L, Andersson M, Isaksson B. Body water and weight in patients with premenstrual tension. BJOG. 1978;85:546–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Andersch B. Bromocriptine and premenstrual symptoms: a survey of double blind trials. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1983;38:643–46. doi: 10.1097/00006254-198311000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ylostalo P, Kauppila A, Puolakka J, Ronnberg L, Janne O. Bromocriptine and norethisterone in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. J Am Coll Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58:292–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wuttke W, Jarry H, Christoffel V, Spengler B, Seidlova-Wuttke D. Chaste tree (Vitex agnus-castus)—pharmacology and clinical indications. Phytomedicine. 2003;10:348–57. doi: 10.1078/094471103322004866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.O’Brien P, Abukhalil I. Randomized controlled trial of the management of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual mastalgia using luteal phase-only danazol. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:18–23. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.O’Brien PM, Craven D, Selby C, Symonds EM. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome by spironolactone. BJOG. 1979;86:142–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1979.tb10582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bancroft J, Rennie D. Perimenstrual depression: its relationship to pain, bleeding, and previous history of depression. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:445–52. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W. Daily record of severity of problems (DRSP): reliability and validity. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9:41–49. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, O’Brien PMS. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2003;3:CD001396. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yonkers KA, Clark RH, Trivedi MH. The psychopharmacological treatment of nonmajor mood disorders. In: Rush AJ, editor. Mood disorders: systematic medication management—modern problems of pharmacopsychiatry. 2. Basel: Karger; 1997. pp. 146–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sundblad C, Modigh K, Andersch B, Eriksson E. Clomipraine effectively reduces premenstrual irritability and dysphoria: a placebo-controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;85:39–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sundblad C, Hedberg MA, Eriksson E. Clomipramine administered during the luteal phase reduces the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome: a placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;9:133–45. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wikander I, Sundblad C, Andersch B, et al. Citalopram in premenstrual dysphoria: is intermittent treatment during luteal phases more effective than continuous medication throughout the menstrual cycle? J Clin Psychopharmaocol. 1998;18:390–98. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199810000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Eriksson E, Nissbrandt H, Sörvik K, et al. Esictalopram in the trestment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15 (suppl 3):S636. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pearlstein TB, Stone AB, Lund SA, Scheft H, Zlotnick C, Brown WA. Comparison of fluoxetine, buproprion, and placebo in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17:261–65. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199708000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Steiner M, Steinberg S, Stewart D, et al. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1529–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506083322301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Stone AB, Pearlstein TB, Brown WA. Fluoxetine in the treatment of late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52:290–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wood SH, Mortola JF, Chan Y-F, Moossazadeh F, Yen SSS. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome with fluoxetine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:339–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cohen L, Miner C, Brown E, et al. Premenstrual daily fluoxetine for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a placebo-controlled, clinical trial using computerized diaries. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:435–44. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Miner C, Brown E, McCray S, Gonzales J, Wohlreich M. Weekly luteal phase dosing with enteric-coated fluoxetine 90 mg in premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Ther. 2002;24:417–33. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)85043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Eriksson E, Hedberg MA, Andersch B, Sundblad C. The serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine is superior to the noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor maprotiline in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;12:167–76. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(94)00076-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Cohen L, Soares C, Yonkers K, Bellew K, Bridges I, Steiner M. Paroxetine controlled release for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a double-blind, placebo-cont rolled trial. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:707–13. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000140005.94790.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Steiner M, Hirschberg A, Bergeron R, Holland F, Gee M, VanErp E. Luteal phase dosing with paroxetine controlled release (CR) in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:352–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yonkers KA, Holthausen GA, Poschman K, Howell HB. Symptom-onset treatment for women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26:198–202. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000203197.03829.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Landen M, Nissbrandt H, Allgulander C, Sorvik K, Ysander C, Eriksson E. Placebo-controlled trial comparing intermittent and continuous paroxetine in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:153–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Freeman E, Rickels K, Sondheimer S, Polansky M. Differential reponse to antidepressants in women with premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:932–39. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Halbreich U, Smoller JW. Intermittent luteal phase sertraline treatment of dysphoric premenstrual syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:399–402. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jermain DM, Preece CK, Sykes RL, Kuehl TJ, Sulak PJ. Luteal phase sertraline treatment for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:328–32. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Young SA, Hurt PH, Benedek DM, Howard RS. treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with sertraline during the luteal phase: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:76–80. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Freeman E, Rickels K, Sondheimer S, Polansky M, Xiao S. Continuous or intermittent dosing with sertraline for patients with severe premenstrual syndrome or premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:343–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Freeman E, Rickels K, Yonkers K, et al. Venlafaxine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:737–44. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01530-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cohen L, Soares C, Lyster A, Cassano P, Brandes M, Leblanc G. Efficacy and tolerability of premenstrual use of venlafaxine (flexible dose) in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:540–43. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000138767.53976.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Freeman EW, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, Polansky M. Differential response to antidepressants in women with premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphonic disorder: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:932–39. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Halbreich U, Bergeron R, Yonkers K, Freeman E, Stout A, Cohen L. Efficacy of intermittent, luteal phase sertraline treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:1219–29. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Watson NR, Studd JW, Savvas M, Garnett T, Baber RJ. Treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome with oestradiol patches and cyclical oral norethisterone. Lancet. 1989;2:730–32. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90784-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Magos AL, Brincat M, Studd JW. Treatment of the premenstrual syndrome by subcutaneous estradiol implants and cyclical oral norethisterone: placebo-controlled study. BMJ. 1986;292:1629–33. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6536.1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Thys-Jacobs S, Starkey P, Bernstein D, Tian J. Calcium carbonate and the premenstrual syndrome: effects on premenstrual and menstrual symptoms. Premenstrual Syndrome Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:444–52. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70377-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Yonkers K, Brown C, Pearlstein T, Foegh M, Sampson-Landers C, Rapkin A. Efficacy of a new low-dose oral contraceptive with drospirenone in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:492–501. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000175834.77215.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Pearlstein T, Bachmann G, Zacur H, Yonkers K. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with a new drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive formulation. Contraception. 2005;72:414–21. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Pearlstein T, Halbreich U, Batzar E, et al. Psychosocial functioning in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder before and after treatment with sertraline or placebo. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:101–09. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Steiner M, Brown E, Trzepacz P, et al. Fluoxetine improves functional work capacity in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2003;6:71–77. doi: 10.1007/s00737-002-0162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Eriksson E, Endicott J, Andersch B, et al. New perspectives on the treatment of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2002;4:111–19. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Steiner M, Pearlstein T, Cohen LS, et al. Expert guidelines for the treatment of severe PMS, PMDD, and comorbidities: the role of SSRIs. J Women’s Health. 2006;15:57–69. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Young SA, Hurt PH, Benedeck DM, Howard RS. Treatment of PDD with sertraline during the luteal phase: a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled crossover trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:76–80. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Freeman E, Sondheimer S, Sammel M, Ferdousi T, Lin H. A preliminary study of luteal phase versus symptom-onset dosing with escitalopram for premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:769–73. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Steiner M, Romano S, Babcock S, et al. The efficacy of fluoxetine in improving physical symptoms associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;108:462–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Steiner M, Haskett RF, Osmun JN, Carroll BJ. Treatment of premenstrual tension with lithium carbonate. A pilot study. Acta Psychiatrica Scand. 1980;61:96–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1980.tb00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Pearlstein TB, Stone AB, Lund SA, Scheft H, Zlotnick C, Brown WA. Comparison of fluoxetine, bupropion, and placebo in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17:261–66. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199708000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Rickels K, Freeman E, Sondheimer S. Buspirone in treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Lancet. 1989;4:777. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Smith S, Rinehart JS, Ruddock VE, Schiff I. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome with alprazolam: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized crossover clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Harrison WM, Endicott J, Nee J. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoria with alprazolam. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:270–75. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810150070011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Freeman EW, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, Polansky M. A double-blind trail of oral progesterone, alprazolam, and placebo in treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome. JAMA. 1995;274:51–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Frischer M, Jones PW, O’Brien SP. Prescribing patterns in premenstrual syndrome. BMC Womens Health. 2002;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Di Carlo C, Palomba S, Tommaselli G, Guida M, Sardo ADS, Nappi C. Use of leuprolide acetate plus tibolone in the treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:380–84. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01707-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Cronje W, Studd J. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Prim Care. 2002;29:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(03)00070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Watson NR, Studd JW, Savvas M, Baber RJ. The long-term effects of estradiol implant therapy for the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1990;4:99–107. doi: 10.3109/09513599009012326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.O’Brien P, Abukhalil I, Henshaw C. Premenstrual syndrome. Curr Obstet Gyneacol. 1995;5:30–35. [Google Scholar]

- 158.Domoney C, Panay N, Hawkins A, Studd JWW. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome with transdermal oestrogen. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83 (suppl 3):37. [Google Scholar]

- 159.Bancroft J, Rennie D. The impact of oral contraceptives on the experience of perimenstrual mood, clumsiness, food craving and other symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:195–202. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90086-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Graham CA, Sherwin BB. A prospective treatment study of premenstrual symptoms using a triphasic oral contraceptive. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36:257–66. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90090-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Sulak P, Scow R, Preece C, Riggs M, Kuehl T. Hormone withdrawal symptoms in oral contraceptive users. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:261–66. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Sulak P, Kuehl T, Ortiz M, Schull B. Acceptance of altering the standard 21-day/7-day oral contraceptive regimen to delay menses and reduce hormone withdrawal symptoms. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1142–49. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Halbreich U, Rojansky N, Palter S. Elimination of ovulation and menstrual cyclicity (with danazol) improves dysphoric premenstrual syndromes. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:1066–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Watts JF, Butt WR, Edwards RL. A clinical trial using danazol for the treatment of premenstrual tensiohn. BJOG. 1987;94:30–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb02248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Hahn PM, Van Vugt DA, Reid RL. A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of danazol for the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20:193–99. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)00053-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Lam R, Carter D, Misri S, Kuan A, Yatham L, Zis A. A controlled study of light therapy in women with late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1999;86:185–92. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]