Abstract

The in vitro antiplasmodial activity of Ambrosia tenuifolia organic extract and its isolated sesquiterpene lactones, psilostachyin and peruvin, has been evaluated against Plasmodium falciparum F32 and W2 strains. The cytotoxicity of both compounds was determined on lymphoid cells, and their corresponding selectivity indexes (SIs) were calculated. Peruvin was the most active compound on F32 strain of P. falciparum with a 50% inhibitory concentration value (IC50) of 0.3 μg/mL (1.1 μM) whereas psilostachyin showed activity on both strains (IC50 = 0.6 (2.1 μM) and 1.8 μg/mL (6.4 μM)). Fifty percent cytotoxic concentration (CC50) values (48 h) were 6.8 μg/mL (24.3 μM) and 10.0 μg/mL (37.9 μM) for psilostachyin and peruvin, respectively.

1. Introduction

Malaria is a major parasitic infection in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, particularly devastating in sub-Saharan Africa where 90% of the cases and deaths occur [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over a million people die from malaria every year, and roughly a 40% of the population is at risk of becoming infected. In America, this infection spreads from Northern to Southern America, being Brazil and the Andes Region, the areas where the greatest number of cases is recorded [2].

Medicinal plants have provided valuable antimalarial drugs such as quinine and artemisinin. The discovery of these drugs, which are currently being used, has prompted the evaluation of other medicinal plants in the search of new antimalarial agents that are not only active against drug-sensitive but also against drug-resistant and multidrug-resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum. Although artemisinin, a sesquiterpene lactone (STL), is the most powerful drug against chloroquine-resistant malaria, resistance to this drug might soon appear. Therefore, there is an urgent need for new therapeutic agents [3].

In previous studies we have demonstrated that the CH2Cl2 : MeOH (1 : 1) of Ambrosia tenuifolia has a significant trypanocidal activity against Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes [4]. Besides, its essential oil showed antiplasmodial activity against chloroquine-sensitive and chloroquine-resistant strains of P. falciparum [5]. A. tenuifolia Sprengel (Asteraceae) is an Argentine medicinal species known as “ajenjo del campo,” “altamisa,” or “artemisia” which is traditionally used for the treatment of intermittent fevers [6, 7].

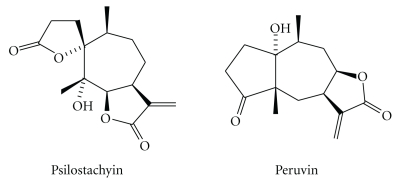

A bioguided assay fractionation of the CH2Cl2 : MeOH (1 : 1) extract of A. tenuifolia led to the isolation of two STLs, belonging to the pseudoguaianolide type, identified as psilostachyin and peruvin (Figure 1). Both compounds were active against T. cruzi and showed antileishmanial activity against Leishmania mexicana promastigotes [8]. The effect of psilostachyin on the growth of T. cruzi epimastigotes with the addition of glutathione and at the ultrastructural level of the parasite has been reported [9].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of sesquiterpene lactones isolated from Ambrosia tenuifolia.

These findings prompted us to assess the activity of A. tenuifolia organic extract and its isolated compounds, psilostachyin and peruvin, on both chloroquine-sensitive (F32) and chloroquine-resistant strains (W2) of P. falciparum. Cytoxicity of such compounds on lymphoid cells has been also tested.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The aerial parts of A. tenuifolia were collected in Punta Lara, Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, in April 2007. The plant material was identified by Dr. G. Giberti, and a voucher specimen (BAF 660) is deposited at the Herbarium of the Museo de Farmacobotánica, Facultad de Farmacia y Bioquímica, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

2.2. Extraction of Plant Material

Dried aerial parts (1000 g) of A. tenuifolia were extracted with CH2Cl2 : MeOH (1 : 1) (10 L) at room temperature for 24 h and vacuum filtered. The process was repeated twice, and the filtrates were combined and dried under vacuum.

2.3. Isolation of Psilostachyin and Peruvin

Psilostachyin and peruvin were isolated from the organic extract of A. tenuifolia as previously described [8]. The purity of psilostachyin and peruvin was confirmed by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) : HPLC-DAD (Waters), gradient H2O : MeOH 0–70% for 20 min, 70–100% for 10 min; C18 column (LiChrospher 5 microns, 125 × 4 mm, Merck) flow 1.0 mL/min.

2.4. Parasite Strains and Culture Media

Plasmodium falciparum F32-Tanzania strain (chloroquine sensitive, kindly provided by Dr. Fandeur T, Pasteur Institute, Kayenne) and P. falciparum W2 strain (chloroquine resistant, kindly provided by Dr Eduardo Ortega Barria, INDICASAT Institute, Panamá) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% human serum and a hematocrit of 4% (Blood group O, RH+) at 37°C in an anaerobic atmosphere [10].

2.5. Animals

Inbred female BALB/c mice (22 ± 2 g) were purchased from the Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA). Animals were kept according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, US National Research Council [11].

2.6. In Vitro Antiplasmodial Activity Assay

Parasite growth was synchronized at 1% parasitemia and 2% hematocrite and distributed in a volume of 100 μL in plates of 96 wells by duplicate. Antiplasmodial activity was evaluated in concentrations between 100 and 0.01 μg/mL for both the organic extract and isolated compounds. 100 μL of each dilution (in DMSO, at no more than 0.1% final concentration) was added to each well. Parasites were then incubated at 37°C for 48 h. After incubation, smears were prepared, fixed with methanol, and stained with Giemsa. The antiplasmodial activity was determined by microscopy counting of noninfected red cells and infected red cells. The 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of the extract and the compounds were calculated graphically using CRICKET GRAPH 1.3 software. Chloroquine (10–1000 nM) (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a positive control, and DMSO was employed as negative control. All assays were carried out in triplicate.

2.7. Cytotoxicity Assay

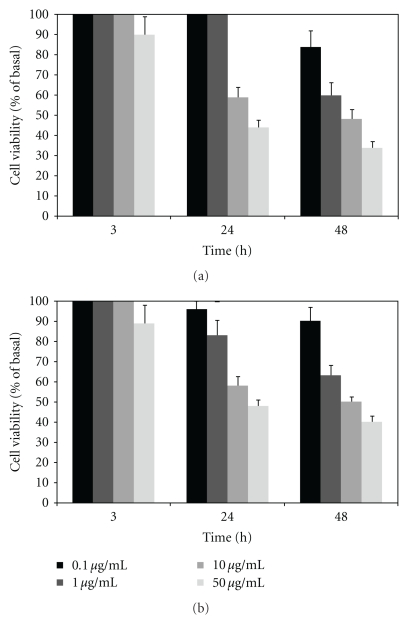

Lymphoid cell suspensions were obtained from the lymph nodes of BALB/c mice as previously reported [8]. Briefly, T-cell enriched populations were obtained by passage of the cell suspension through a nylon wool column. T-cell presence was higher than 97% as checked by indirect immunofluorescence after lysis with anti-Thy plus complement. Cells were cultured at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were adjusted to a final volume of 0.2 mL per well in a 96-well microtiter plate and cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 3, 24, and 48 h. Cell viability was determined by the trypan blue exclusion method in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of the compounds (0.1, 1, 10, and 50 μg/mL) and was expressed as % of basal values, calculated as [number of viable cells/number of total cells] × 100. Then, data of viability were transformed in cytotoxicity values (100-% of viability) to calculate the 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) which was finally calculated using CRICKET GRAPH 1.3 software. The tests were performed in triplicate. The selectivity index (SI) was used to compare the toxicity for mammalian cells and the activity against the parasites and calculated as the CC50 on murine T lymphocytes (48 h) divided by the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of the compound for both strains of P. falciparum.

3. Results and Discussion

The organic extract of Ambrosia tenuifolia was assayed in vitro on P. falciparum F32 strain. This extract showed promising antiplasmodial activity with a growth inhibition of 77.1 ± 1.22% (10 μg/mL), with an IC50 value of 2 μg/mL (Table 1). Psilostachyin and peruvin, two STLs isolated from this extract, were tested for their ability to inhibit the same P. falciparum strain and a chloroquine-resistant strain (W2). These STLs were active on both parasite strains but showed stronger activity on the F32 strain. Peruvin was the most active compound on this strain with an IC50 value of 0.3 μg/mL (1.1 μM) whereas psilostachyin showed activity on both F32 and W2 strains with IC50 values of 0.6 (2.1 μM) and 1.8 μg/mL (6.4 μM), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

In vitro antiplasmodial activity, cytotoxicity and selectivity indexes of Ambrosia tenuifola extract, psilostachyin and peruvin.

| Extract/Compounds | IC50 (μM) | CC50 (μM) | Selectivity Index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. falciparum | P. falciparum | 48 h | P. falciparum | P. falciparum | |

| F32 strain | W2 strain | F32 strain | W2 strain | ||

| CH2Cl2 : MeOH (1 : 1) | 2.0 ± 0.09* | n.t. | n.t. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Psilostachyin | 2.1 ± 0.15 | 6.4 ± 0.48 | 24.3 ± 0.21 | 11.6 ± 0.95 | 3.8 ± 0.25 |

| Peruvin | 1.1 ± 0.09 | 18.9 ± 0.95 | 37.9 ± 0.34 | 34.4 ± 2.40 | 2.0 ± 0.15 |

| Chloroquine | 0.03 ± 0.002 | 2.8 ± 0.19 | n.t. | n.c. | n.c. |

n.t.: not tested; n.c.: not calculated.

*Expressed as μg/ML.

The isolated compounds were evaluated for their cytotoxicity on T-cells at 3, 24 and 48 h (Figure 2). The CC50 values (48 h) for psilostachyin and peruvin and the SIs were calculated and are shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Effects of psilostachyin (a) and peruvin (b) on T-lymphocyte viability. Cultures were done in 96-well plates with 2 × 106 lymphocytes/mL during 3, 24 or 48 h in the presence of different concentrations (0.1 to 50 μg/mL) of the compounds. Cell viability was determined by the trypan blue exclusion method and is expressed as viability. Bars represent the means ± SEM.

This is the first report on the antiplasmodial activity of psilostachyin and peruvin. The IC50 values for these compounds were in the μM range as it has been reported for other STLs [12] and particularly for pseudoguaianolides such as helenalin and its ester derivatives [13].

Antiplasmodial activity of this kind of compounds has been usually associated with high cytotoxicity [14, 15]. However, certain STLs, mainly from the pseudoguaianolide type, are considerably more toxic to the parasites than to mammalian cells [13]. These findings suggest that other structural features are governing the antiplasmodial activity of this kind of compounds besides the effect related to the α-methylene-γ-lactone group (Michael addition).

Since the discovery of artemisinin against chloroquine-resistant malaria, attention has been paid to other STLs as a potential source of antimalarial drugs. The results shown herein for psilostachyin and peruvin, on P. falciparum, make these molecules interesting scaffolds to generate leads with enhanced antiplasmodial activity and reduced cytotoxicity. Further investigation will include the in vivo studies and the molecular mechanism of action of these compounds.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. G. Giberti from the Museo de Farmacobotánica, Facultad de Farmacia y Bioquímica, Universidad de Buenos Aires, for collection and classification of plant material. This work was supported by funds from University of Buenos Aires (Grant nos. B030, 20020090300115); Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Grant no. PIP 01540); Programa Iberoamericano de Ciencia y Tecnología para el Desarrollo (Grant no. X5); Flora Regional OEA project.

References

- 1.Kaur K, Jain M, Kaur T, Jain R. Antimalarials from nature. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;17(9):3229–3256. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. World Health Organization. Fact Sheet 94: WHO information. 2010, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs094/en/index.html.

- 3.Park WH, Lee SJ, Moon HI. Antimalarial activity of a new stilbene glycoside from Parthenocissus tricuspidata in mice. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2008;52(9):3451–3453. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00562-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sülsen V, Güida C, Coussio J, Paveto C, Muschietti L, Martino V. In vitro evaluation of trypanocidal activity in plants used in Argentine traditional medicine. Parasitology Research. 2006;98(4):370–374. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-0060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sülsen VP, Cazorla SI, Frank FM, et al. In vitro antiprotozoal activity and chemical composition of Ambrosia tenuifolia and A. scabra essential oils. Natural Product Communications. 2008;3(4):557–562. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hieronymus J. Plantae diaphoricae florae Argentinae. Bol Acad Nac Cien Córdoba. 1882;4:345–346. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ratera E, Ratera M. Plantas de la Flora Argentina Empleadas en Medicina Popular. Buenos Aires, Argantina: Hemisferio Sur; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sülsen VP, Frank FM, Cazorla SI, et al. Trypanocidal and leishmanicidal activities of sesquiterpene lactones from Ambrosia tenuifolia Sprengel (Asteraceae) Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2008;52(7):2415–2419. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01630-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sülsen V, Barrera P, Muschietti L, Martino V, Sosa M. Antiproliferative effect and ultrastructural alterations induced by psilostachyin on Trypanosoma cruzi . Molecules. 2010;15(1):545–553. doi: 10.3390/molecules15010545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trager W, Jensen JB. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193(4254):673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington, DC, USA: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bero J, Quetin-Leclercq J. Natural Products published in 2009 from plants traditionally used to treat malaria. Planta Medica. 2011;77(6):631–640. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1250405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt TJ, Nour AMM, Khalid SA, Kaiser M, Brun R. Quantitative structure—antiprotozoal activity relationships of sesquiterpene lactones. Molecules. 2009;14(6):2062–2076. doi: 10.3390/molecules14062062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pillay P, Vleggaar R, Maharaj VJ, Smith PJ, Lategan CA. Isolation and identification of antiplasmodial sesquiterpene lactones from Oncosiphon piluliferum . Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;112(1):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chukwujekwu JC, Lategan CA, Smith PJ, Van Heerden FR, Van Staden J. Antiplasmodial and cytotoxic activity of isolated sesquiterpene lactones from the acetone leaf extract of Vernonia colorata . South African Journal of Botany. 2009;75(1):176–179. [Google Scholar]