Abstract

Noonan syndrome, a developmental disorder characterized by congenital heart defects, reduced growth, facial dysmorphism and variable cognitive deficits, is caused by constitutional dysregulation of the RAS-MAPK signaling pathway. Here we report that germline NRAS mutations conferring enhanced stimulus-dependent MAPK activation account for some cases of this disorder. These findings provide evidence for an obligate dependency on proper NRAS function in human development and growth.

The KRAS, NRAS and HRAS genes encode highly conserved small GTPases that act as membrane-associated molecular switches controlling intracellular signal flow by cycling between active, GTP-bound states and inactive, GDP-bound states1. Following the transmission of signals elicited by cell surface receptors, RAS proteins are activated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors. In the GTP-bound state, two regions, switch I and switch II, undergo a conformational change that enables RAS proteins to bind to and activate effector proteins, including RAF and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinases2. This interaction is terminated by hydrolysis of GTP to GDP, which promotes a switch toward the inactive RAS conformation. The low intrinsic GTPase activity of RAS proteins is enhanced by GTPase activating proteins (GAPs)3. Because of its nodal role in signal transduction, RAS function is required for many cellular processes, and its upregulation has been causally linked to oncogenesis and developmental disorders2,4. These developmental disorders comprise a group of clinically related conditions characterized by facial dysmorphism, congenital cardiac defects, reduced growth and variable cognitive impairment and tumor predisposition. In these disorders, RAS signaling dysregulation is caused by germline mutations in HRAS or KRAS as well as in genes encoding modulators of RAS function (PTPN11, SOS1, SHOC2, NF1 and SPRED1) or downstream signal transducers (RAF1, BRAF, MEK1 and MEK2)4–7. The common biological consequence of mutations associated with this group of diseases is altered, usually increased, signal traffic through the MAPK cascade.

Based on the evidence that Noonan syndrome (MIM163950) and the clinically related cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome (MIM115150) are genetically heterogeneous, with mutations in known disease genes accounting for 70–80% of cases of each6,7, a systematic scanning of the NRAS gene was performed on a cohort of 917 individuals negative for previously known mutations with a phenotype fitting or suggestive of these disorders (Supplementary Methods). We identified four unrelated individuals in this cohort heterozygous for the nucleotide changes C149T or G179A (resulting in the amino acid substitutions T50I and G60E, respectively) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Three were sporadic cases, and parental DNA genotyping demonstrated the de novo origin of the mutations. The defects were documented in hair bulbs, urine exfoliated cells and/or buccal epithelial cell specimens, thus excluding a somatic event restricted to blood cells as the cause of the mutations (Supplementary Fig. 1 and data not shown). In the family transmitting the trait, the mutation segregated with disease. All NRAS mutation–positive subjects showed typical clinical features of Noonan syndrome (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

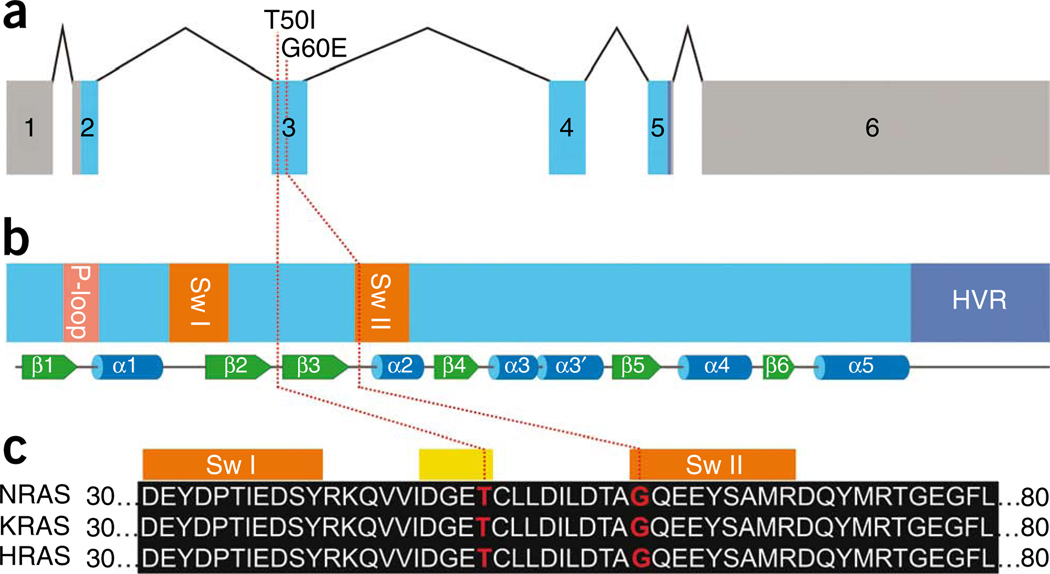

Figure 1.

NRAS genomic organization and protein structure and position of Noonan syndrome–causing NRAS mutations. (a) Exon-intron structure of the human NRAS gene showing untranslated regions as gray boxes and coding exons as blue boxes. (b) Motifs and secondary structures of the NRAS protein. Functional motifs including the P-loop, switch I (Sw I), switch II (Sw II) and the hypervariable region (HVR) are highlighted. Underneath, secondary structural elements are shown as green arrows and blue cylinders representing β-sheets and α-helices, respectively. (c) Partial amino acid sequence alignment of human NRAS, KRAS and HRAS showing conservation of Thr50 and Gly60 (red). Orange boxes on top of the alignment mark amino acids comprising the switch I and II regions, and the yellow box marks the four amino acids of the β2−β3 loop. Red dotted lines in panels a to c indicate the positions of nucleotides and amino acids, respectively, affected by Noonan syndrome-causing mutations.

Both NRAS mutations affected amino acid residues highly conserved among RAS orthologs and paralogs (Fig. 1c and data not shown). Gly60 is located in the switch II region. A germline KRAS mutation affecting Gly60 (G60R) had previously been reported in cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome8, and the somatic NRAS mutation G60E rarely occurs in malignancies (COSMIC database; see URLs below). Alterations of the neighboring Gln61 are frequent among oncogenic RAS alterations and are known to confer impaired GTPase function. In contrast, no somatic or germline RAS gene mutation affecting Thr50 has been described so far. Thr50 is an exposed residue located in the β2–β3 loop connecting the two switch regions (Fig. 1b) but is not predicted to be directly involved in GTP and GDP binding, GTP hydrolysis, or effector interaction (Supplementary Fig. 3).

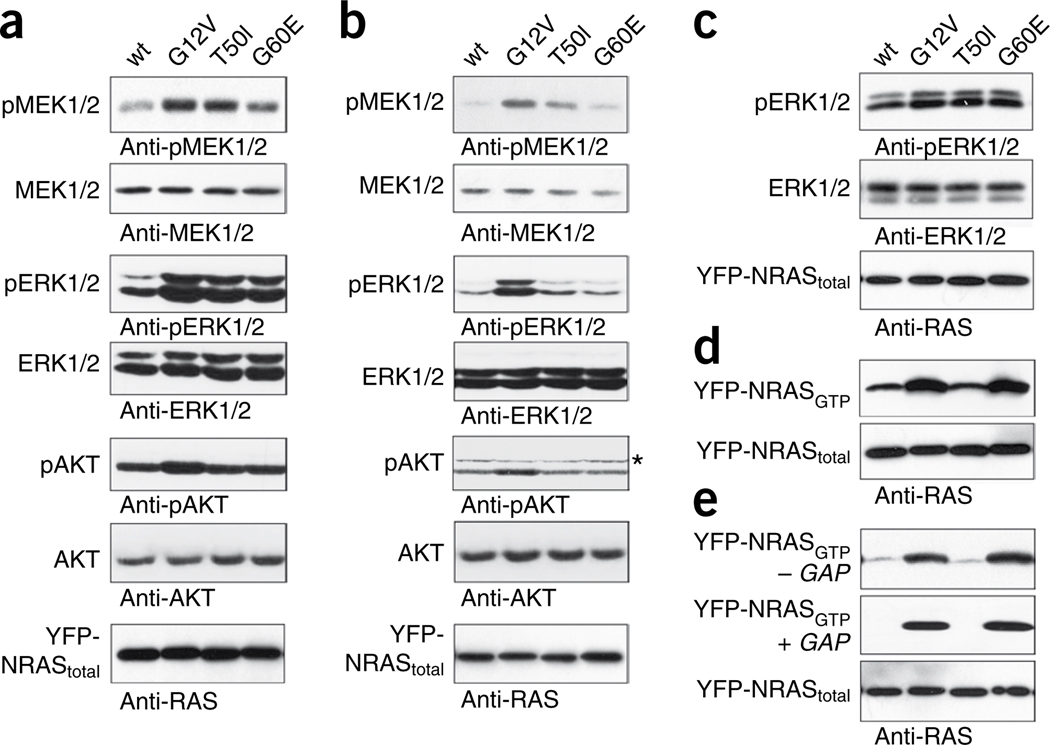

To elucidate the consequences of the Noonan syndrome–causing NRAS mutations on protein function and intracellular signaling, we expressed each mutant as yellow fluorescent protein–NRAS fusion proteins in cells from the COS-7 line, and their functional properties in vitro were compared with wild-type NRAS and the oncogenic NRAS substitution G12V, where the latter is known to be GAP resistant and to promote constitutive activation of MAPK signaling. Expression of the NRAS substitutions T50I or G60E resulted in enhanced phosphorylation of MEK and ERK in the presence of serum or after epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulation but, in contrast with the G12V NRAS substitution, had only marginal effects on signaling in starved cells (Fig. 2a–c). Of note, the G60E NRAS mutant, much like G12V, accumulated constitutively in the active, GTP-bound form and appeared resistant to GAP stimulation. In contrast, the T50I NRAS mutant was not enriched in the GTP-bound state (Fig. 2d,e), indicating a different mechanism of functional dysregulation. Biochemical characterization of this alteration provided evidence that the T50I substitution does not substantially affect intrinsic GTPase activity, GAP association or GAP-stimulated hydrolysis. Similarly, no change was observed in guanine nucleotide exchange factor–catalyzed nucleotide release, effector association or allosteric activation of SOS1 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

Biochemical characterization of the Noonan syndrome–causing T50I and G60E NRAS mutants. (a,b) Determination of MEK, ERK and AKT phosphorylation levels in transiently transfected COS-7 cells cultured in medium with serum (a) or in basal medium (b). Expression of each of the three NRAS mutants (G12V, G60E and T50I) resulted in enhanced MEK and ERK phosphorylation in the presence of serum, whereas only the oncogenic G12V substitution substantially stimulated phosphorylation of MEK and ERK in serum-deprived cells. Contrasting with what was observed for the G12V change, no effect on AKT phosphorylation was detectable in cells expressing the Noonan syndrome–causing T50I or G60E mutant under both culture conditions. Asterisk beside the pAKT blot marks artifactual bands (Supplementary Fig. 7). Total amounts of MEK, ERK and AKT in cell lysates are shown for equal protein expression and loading. (c) EGF stimulation of serum-starved cells reproduced the effects on ERK phosphorylation observed in the presence of serum. (d) Determination of GTP-bound NRAS levels in COS-7 cells transiently expressing wild-type NRAS or each mutant in the presence of serum. Similar to the oncogenic G12V mutant, G60E, but not T50I, accumulated in the GTP-bound form. (e) The same experiment was performed under serum-free conditions. Both the G12V and G60E mutants were predominantly present in the active GTP-bound form, whereas the T50I mutant was not. Addition of purified RasGAP left GTP-bound levels of the G12V and G60E mutants unaffected, demonstrating GAP resistance of these mutants, in contrast to the T50I mutant. Total amounts of exogenous (yellow fluorescent protein-tagged) NRAS in cell lysates are shown for each experiment (a–e). Specificity of the antibody employed in each experiment is indicated below each panel. Wt, wild type.

To explore further the structural and functional consequences of the T50I change, we determined the crystal structure of the RAS mutant bound to Gpp(NH)p (an analog of GTP), but no substantial structural rearrangements were observed (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 5). Molecular dynamics simulations of wild-type RAS indicated that Thr50 directly interacts with the polar heads of membrane phospholipids and is an integral part of a recently described functional region that controls RAS membrane orientation and signal output (Supplementary Fig. 6)9. According to this model, aside from the conformational changes involving the switch I and II regions, GTP loading of membrane-anchored RAS is predicted to rearrange a distinct region of the GTPase (comprising the β2–β3 loop and helix α5) (Fig. 1c,d). This, in turn, would lead to a differential engagement of the C-terminal hypervariable region and helix α4 with the membrane, ultimately altering the orientation of the entire G domain of RAS with respect to the membrane. Residues Asp47 and Glu49 have been shown to be directly involved in the intermolecular binding network controlling RAS membrane orientation, and their substitution was found to enhance downstream signaling through GTP-bound RAS, presumably by keeping the GTPase in a more signaling-competent orientation9. Consistent with this model, the RASbinding domain of RAF1 is able to recognize the relative membrane orientation of GTP-bound RAS, which is functionally translated into different signaling outputs9. Based on this model, we hypothesize that the T50I substitution might alter RAS orientation in a fashion similar to that documented for the D47A and E49A substitutions9 (Supplementary Fig. 6), bolstering the interaction of GTP-bound RAS with its effectors. This proposed mechanism would explain the enhanced signal flow through the MAPK cascade in the absence of any substantial accumulation of the T50I NRAS substitution in its GTP-bound form (Fig. 2). Taken together, these findings support the idea that Noonan syndrome–causing NRAS mutants are weak hypermorphs. Although the G60E NRAS substitution accumulates in its GTP-bound form to mimic the consequences of oncogenic substitutions affecting Gly12 or Gly13, the weakened effector binding of this mutant might account for its damped downstream effect compared to the oncogenic G12V alteration.

Here we reported that Noonan syndrome can be caused by altered signaling through NRAS. Similar to what has been observed for germline KRAS mutations causing Noonan syndrome and cardiofacio- cutaneous syndrome, germline NRAS alterations do not affect residues commonly mutated in human cancers and appear to be less activating in dysregulating intracellular signaling in vitro compared with cancer-associated somatic mutations. Considering the large size of the cohorts of affected individuals included in this study, germline NRAS mutations are estimated to be substantially less frequent than those affecting KRAS or HRAS7. Although we favor the hypothesis that NRAS mutations rarely occur as germline defects because of their severe consequences on embryonic and fetal development, we cannot exclude the possibility that mutations other than those described here may cause phenotypes not recognized as Noonan syndrome or related disorders. Notably, Oliveira and colleagues reported on an individual with a germline NRAS missense change (G13D) and an autoimmune lymphoproliferative disorder, without any signs of Noonan syndrome10. Although their observation has not been replicated so far, their findings could be consistent with the occurrence of non-overlapping allele-specific phenotypic effects resulting from different NRAS mutations than those described here.

The identification of activating NRAS mutations in Noonan syndrome provides evidence for an obligate dependency on proper function of this small GTPase in human development and growth. Even though functional redundancy among RAS proteins does exist, biological differences in these proteins are also well documented11,12. Recent evidence gathered from mouse models demonstrated that these GTPases play distinct roles in development. Although loss of Kras isoforms is lethal at the embryonic stage, disruption of mouse Hras and Nras does not meaningfully perturb development. Consistently, it has been documented that RAS proteins generate distinct signal outputs despite their interaction with a shared set of activators and effectors11,12, and preferential associations between specific human cancers and individual RAS genes have also been established (see COSMIC database). These and recent findings regarding Noonan syndrome and related disorders extend this concept to germline mutations and human development, showing that distinct clusters of activating mutations in the three RAS genes underlie a group of clinically related mendelian traits. Notably, whereas a small number of mutations in HRAS and NRAS underlie, respectively, Costello syndrome (MIM218040) and Noonan syndrome, a more diverse set of missense changes in KRAS results in a markedly broad phenotypic continuum13. Further studies are required to understand such genotype-phenotype correlations. The localization of RAS isoforms to distinct signaling nanoclusters and their ability to differentially activate canonical and non-canonical pathways, rather than distinct tissue- or cell-specific expression patterns, are believed to underlie the functional diversity of these GTPases11,12,14. Accordingly, phenotypic differences between Noonan, cardio-facio-cutaneous and Costello syndromes might be ascribed to different developmental consequences strictly depending upon these mechanisms, although the obvious similarities of these disorders testify that there are important functions in developmental programs that are shared by all members of this family of GTPases.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, the Istituto Superiore di Sanità, IRCCS–Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, and the Children′s Hospital Boston and Partners HealthCare, Boston. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects participating in the study and/or their parents.

URLs. COSMIC database, http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/cosmic/.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the subjects and their families for participating in this study. We thank A. Diem and B. Quinger (Institute of Human Genetics, Erlangen, Germany), T. Squatriti and S. Venanzi (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy) and I. Jantke and S. Lorenz (Institut für Humangenetik, Hamburg, Germany) for skillful technical assistance. The X-ray diffraction datasets were collected at the Swiss Light Source, beamline X10SA, Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen, Switzerland. This work was supported by grants from the European Research Area Network for research programs on rare diseases (E-Rare) 2009 to M.T., M.Z. and M.R.A. (European Network on Noonan Syndrome and Related Disorders), German Research Foundation (DFG) to M.R.A. (AH 92/5-1) and C.P.K. and M.Z. (KR 3473/1-1 and ZE 524/4-1), Nationales Genomforschungsnetz Plus program of the German Ministry of Science and Education to M.R.A. (BMBF, grant 01GS08100), and Telethon-Italy (GGP07115), ‘Associazione Italiana Sindromi di Costello e Cardiofaciocutanea’ and ‘Collaborazione Italia-USA/malattie rare’ to M.T.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Genetics website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.K., C.C., D.H., F.L., F.P., M.L.D., V.A.J. and C.R. performed mutation analysis and genotyping. L.A.P. performed high-throughput resequencing. L.S. performed the NRAS copy number analysis. R.K., A.E.R., L.M., S.M., M.A.P., M.C.S., G.Z., C.D., E.S., B.D. and M.Z. obtained DNA specimens from affected individuals and did clinical evaluations. R.D. and L.G. determined crystal structure. R.D. performed molecular dynamics simulations and structural analyses. I.C.C., L.G., T.M.-Z. and A.W. carried out biochemical and functional studies. C.P.K., R.S.K. and B.D.G. did project planning and data analysis K.K. participated in preparation of the manuscript. M.R.A., M.T. and M.Z. carried out the project planning and participated in data analysis and preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Vetter IR, Wittinghofer A. Science. 2001;294:1299–1304. doi: 10.1126/science.1062023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karnoub AE, Weinberg RA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:517–531. doi: 10.1038/nrm2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmadian MR, Hoffmann U, Goody RS, Wittinghofer A. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4535–4541. doi: 10.1021/bi962556y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordeddu V, et al. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1022–1026. doi: 10.1038/ng.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denayer E, de Ravel T, Legius E. J. Med. Genet. 2008;45:695–703. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.055772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tidyman WE, Rauen KA. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2009;19:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niihori T, et al. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:294–296. doi: 10.1038/ng1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abankwa D, et al. EMBO J. 2008;27:727–735. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliveira JB, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8953–8958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702975104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancock JF. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:373–384. doi: 10.1038/nrm1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quinlan MP, Settleman J. Future Oncol. 2009;5:105–116. doi: 10.2217/14796694.5.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zenker M, et al. J. Med. Genet. 2007;44:131–135. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.046300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haigis KM, et al. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:600–608. doi: 10.1038/ngXXXX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.