Abstract

The development of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is a complex process involving both parenchymal and nonparenchymal cells resident in the liver. Although the mechanisms for ALD are not completely understood, it is clear that increased oxidative stress, and activation of the innate immune system are essential elements in the pathophysiology of ALD. Oxidative stress from ethanol exposure results from increased generation of reactive oxygen species and decreased hepatocellular antioxidant activity, including changes in the thioredoxin/peroxiredoxin family of proteins. Both cellular and circulating components of the innate immune system are activated by exposure to ethanol. For example, ethanol exposure enhances toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4)-dependent cytokine expression by Kupffer cells, likely due, at least in part, to dysregulation of redox signaling. Similarly, complement activation in response to ethanol leads to increased production of the anaphylatoxins, C3a and C5a, and activation C3a receptor and C5a receptor. Complement activation thus contributes to increased inflammatory cytokine production and can influence redox signaling. Here we will review recent progress in understanding the interactions between oxidative stress and innate immunity in ALD. These data illustrate that ethanol-induced oxidative stress and activation of the innate immune system interact dynamically during ethanol exposure, exacerbating ethanol-induced liver injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15, 523–534.

Introduction

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) develops in ∼20% of all alcoholics with a higher prevalence in women (56). The development of fibrosis and cirrhosis is a complex process involving both parenchymal and nonparenchymal cells resident in the liver, as well as the recruitment of other cell types to the liver in response to damage and inflammation (28). The mechanisms for ethanol-induced damage in the liver are complex; however, it is clear that increased oxidative stress, and activation of the innate immune system are essential elements in the pathophysiology of ALD. Both cellular and circulating components of the innate immune system are activated by exposure to ethanol. There is a growing appreciation that ethanol-induced oxidative stress and activation of the innate immune system interact dynamically during ethanol exposure; this interaction likely exacerbates ethanol-induced liver injury. Here we will review some of the recent findings on the interactions between oxidative stress and innate immunity in the progression of ALD.

Pathways Leading to Increased Reactive Oxygen in ALD

Cellular sources for reactive oxygen in liver during ethanol exposure

Chronic ethanol consumption induces oxidative stress via several mechanisms. Ethanol metabolism by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase produces excessive amounts of reducing intermediates by converting NAD to NADH, resulting in altered redox balance (57). The metabolic process produces acetaldehyde, a toxic and reactive compound that impairs mitochondrial function leading to increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (18). Metabolism by the microsomal ethanol oxidizing system (MEOS) pathway, represented by cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1), induces oxidative stress. Ethanol consumption increases CYP2E1 synthesis and decreases CYP2E1 degradation in hepatocytes both in vivo and in vitro (21, 86). Chronic ethanol exposure also induces CYP2E1 expression in Kupffer cells (11, 101). Induction of CYP2E1 promotes transition of hepatic stellate cells from a quiescent to active state potentially resulting in fibrosis and cirrhosis (47). In addition to inducing CYP2E1, chronic ethanol exposure increases NADPH oxidase activity and increases the production of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide (20, 84, 101). Ethanol also induces the conversion of xanthine dehydrogenase to xanthine oxidase, leading to increased ROS production and oxidative stress (76). Because ethanol metabolism requires a great deal of oxygen, ethanol catabolism results in hypoxia in the liver. Hypoxia during ethanol metabolism also contributes to subsequent increases in reactive oxygen and oxidative stress (117).

Activation of hepatic macrophages (Kupffer cells) is an important source of oxidative stress during ethanol exposure. Long-term exposure to ethanol results in commensal bacterial overgrowth in the jejunum (4). The increase in microflora, coupled with a disruption of the barrier function of the small intestine in response to ethanol, increases the translocation of Gram-negative bacteria into the portal circulation (46, 83). The concentration of endotoxin is increased in the blood of both rats and mice exposed to ethanol via intragastric feeding, as well as in humans who partake in alcohol consumption (26, 74, 103). In rats, when the presence of Gram-negative bacteria is reduced by treatment with antibiotics, the effects of ethanol on liver injury are also reduced (73). Because the liver is the first capillary bed through which the portal blood passes, the liver is the first organ to respond to increased endotoxin or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the portal circulation. Kupffer cells detoxify this blood and clear LPS from circulation. LPS activates Kupffer cells, leading to the production of inflammatory mediators, including cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and ROS.

Regulation of antioxidant pathways in liver during ethanol exposure

Small molecular antioxidants

Modulation of glutathione

Although it is clear that oxidant stress plays a critical role in the initiation and progression of ethanol-induced liver injury (2), treatment with antioxidants has met with limited success in small animal models of ALD, as well as in patients with ALD. These treatment strategies have been based on our understanding for the molecular effects of ethanol on endogenous antioxidant pathways in the liver. Chronic ethanol exposure impairs transport of the endogenous antioxidant glutathione (GSH) into the mitochondria, sensitizing the cell to TNF-α-mediated damage (16). In addition, ethanol decreases the GSH/oxidized glutathione (GSSG) ratio in the cytosol of hepatocytes, resulting in a shift in redox balance (89). In mice, treatment with the GSH precursor N-acetylcysteine (NAC) increased the GSH/GSSG ratio and protects against oxidative damage and hepatocyte injury; however, the mice still had ethanol-induced increases in TNF-α (89).

Ethanol exposure disrupts methionine metabolism, decreasing hepatic S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) concentrations. There is a resulting shift in the homeostasis of the methionine cycle, resulting in increased S-adenosyl homocysteine (SAH) and homocysteine concentrations (Fig. 1). Ethanol-induced shifts in the equilibrium of the methionine cycle are thought to contribute to decreased GSH synthesis and contribute to increased oxidative stress (44). While the mechanisms for changes in the methionine cycle are not well understood, SAM supplementation has been successfully used to prevent ethanol-induced liver injury in both mouse (55) and rat models (99). However, clinical trials in humans are not conclusive (62). Supplementation with NAC or betaine, a methyl donor for methionine metabolism, also restores balance to this pathway, decreasing homocysteine and restoring GSH levels (44, 106, 110, 114). In addition to restoring balance to methionine metabolism, betaine may have additional effects in liver, such as shifting ethanol metabolism from CYP2E1 to catalase-dependent pathways, thus reducing oxidative stress (80), decreasing toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4) expression (94), improving secretion of very low density lipoproteins by restoring phosphatidyl choline biosynthesis (99), and suppressing ethanol-induced apoptosis (44). Thus, while shifts in the methionine cycle have been associated with depletion of GSH and oxidative stress, more recent data indicate that the hepatocellular response to disruption in the methionine cycle is much more complex.

FIG. 1.

The methionine cycle and taurine synthesis. THF, tetrahydrofolate; MS, methionine synthase; BHMT, betaine homocysteine methyltransferase; SAM, S-adenosyl methionine; SAH, S-adenosyl homocysteine.

Vitamin E

The potential protective properties of vitamin E have also investigated in animal models of ALD. Mice treated with vitamin E are protected from oxidative damage; however, they still have increases in ethanol-induced inflammation, hepatic triglyceride accumulation, and hepatocyte damage (72).

Other small molecules with antioxidant activity

Taurine, also known as 2-aminoethanesulphonic acid, is one of the most abundant amino acids in humans and rodents. Taurine is found in high concentrations (mM level) in most of the mammalian tissues (32). Taurine is synthesized from methionine and cysteine in the liver (Fig. 1) and it is not considered as an essential amino acid for most of the mammals. While taurine cannot scavenge ROS directly, it protects cells from oxidative stress. This protective effect may be due to the ability of taurine to react with dicarbonyl intermediates, effectively scavenging the reactive carbonyl and glycation intermediates, particularly due to its high concentration in most tissues (32). Taurine also increases cellular antioxidant capacity by increasing the expression of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (6).

Taurine supplementation inhibits Kupffer cell activation and decreases the production of inflammatory cytokine production by macrophages (3) and prevents ethanol-induced steatosis and oxidative stress in rats (13). Since taurine is nontoxic and is widely used to supplement infant formulas and energy drinks (65), further investigations into its protective effect in ameliorating ethanol-induced oxidative stress and injury are warranted (31).

Antioxidant proteins.

Strategies to enhance the antioxidant capacity of cells during ethanol-induced oxidative stress are also likely to protect from ethanol-induced liver injury. Key enzymes that prevent oxidative stress include SOD and catalase. Mice deficient in SOD exhibit increased sensitivity to ethanol-induced liver injury (48), whereas SOD mimetics protect hepatocyte cell lines from oxidative damage (79). This is similar to the protective effects of taurine supplementation on oxidative stress in the liver of rats during ethanol exposure associated with increased expression of SOD and catalase (13).

Small disulphide-containing redox proteins in the thioredoxin (Trx) and peroxiredoxin family also contribute to the maintenance of redox balance in cells. Trx is a 12 kDa redox-sensitive protein involved in maintaining intracellular redox balance, promoting cell growth, and inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis (8). Trx scavenges and reduces ROS via a family of proteins known as peroxiredoxins (71) (Fig. 2). There are at least six isoforms of the peroxiredoxins, each functions to reduce hydroperoxides, with peroxiredoxin 6 also acting to reduce lipid peroxides (45).

FIG. 2.

Thioredoxin (Trx) is an endogenous protein with antioxidant and antiapoptotic properties. Trx scavenges and reduces reactive oxygen species via a family of proteins known as peroxiredoxins. Additionally, Trx reduces oxidized proteins. Once oxidized, Trx is reduced by the enzyme thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) and the hydrogen donor NADPH. Trx is upstream of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase-1 (ASK-1), a protein involved in apoptosis, and prevents activation, signaling, and induction of apoptosis.

Trx is ubiquitously expressed and has three isoforms: Trx-1 in the cytosol, Trx-2 in the mitochondria, and Trx-3 in the endoplasmic reticulum. Trx functions as an antioxidant and can also reduce oxidized proteins. The two cysteine residues in Trx active site act as hydrogen donors and can reduce target proteins. Once Trx-1 is oxidized, it can be reduced by Trx reductase (36) (Fig. 2). When exogenous stresses, such as ROS, are introduced to the cell, Trx-1 translocates into the nucleus and increases in expression of Trx-1 occur after ∼1 h (38).

In addition to its role as a general free radical scavenger, the antioxidant properties of Trx-1 are critical in the regulation of several redox-sensitive signaling pathways. This specific function is generally considered to convey Trx-1 with anti-inflammatory properties. Trx suppresses the LPS-stimulated activation of p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) located upstream of the inflammatory cytokine TNF-α (70), by preventing the activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase-1 (ASK-1), a MAPKK located upstream of p38 and JNK (41) (Fig. 2). Trx also has antiapoptotic properties, since ASK-1 is also located upstream of caspase-3 in the apoptotic signaling pathway (33) (Fig. 2).

Since the redox-sensitive protein Trx-1 and the family of peroxiredoxin proteins provide a critical link between redox signaling and innate immune responses, several groups have initiated investigations into the effects of ethanol on the function and activity of these redox proteins, as well as their potential role as a useful therapeutic strategy for the treatment of ALD. Recent studies have found that ethanol feeding to mice rapidly reduces the quantity of Trx-1 protein (14), as well as peroxiredoxin 6 (88). Importantly, when mice are supplemented with recombinant human Trx-1 during 4 days of ethanol feeding, they are protected from ethanol-induced oxidative stress (14). Markers of hepatic injury, including apoptosis, cytokine expression, and steatosis, were also ameliorated with treatment with recombinant human Trx-1 (14). In contrast, when peroxiredoxin 6 transgenic mice were fed ethanol over 9 weeks, no protection was observed (87). These recent studies identify the Trx/peroxiredoxin family as an important target of ethanol exposure in animal models. Further studies will be required to more completely interrogate the regulation of the Trx/peroxirdoxin pathway in ALD.

Innate Immune Pathways Activated in ALD: Interactions with Redox Signaling

Cell-based activity of the innate immune system

Kupffer cells and TLRs.

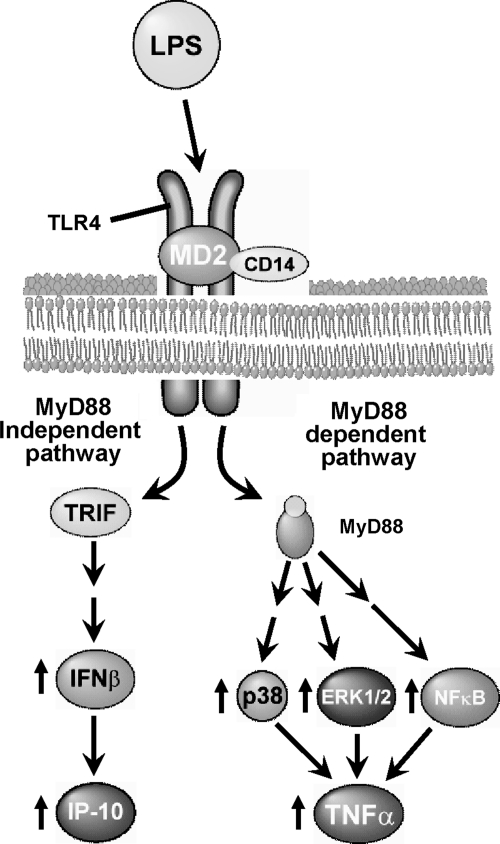

Cellular components of the innate immune response, including NK and NKT cells (66), dendritic cells (39, 77), and Kupffer cells (68), contribute to ethanol-induced liver injury. Kupffer cells are particularly critical to the progression of ethanol-induced liver disease. Treatment with the macrophage toxin gadolinium chloride depletes Kupffer cells and prevents ethanol-induced liver injury in rats (1). LPS-mediated signaling is also essential for the progression of ethanol-induced liver injury. LPS signaling occurs when LPS and LPS-binding protein (LBP) attach to the cell surface receptor CD14. CD14, interacting with TLR-4, comprises two major components of the LPS receptor complex. Activation of the LPS receptor complex stimulates a number of signal transduction cascades (98) (Fig. 3). Mice that lack LPS receptor components (CD14, TLR-4, and LBP) are protected from chronic ethanol-induced liver injury after intragastric ethanol exposure (97, 105, 115).

FIG. 3.

Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4) signaling via MyD-88-dependent pathways. Chronic ethanol exposure increases lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the circulation, and initiates a signaling cascade via TLR-4 on the surface of Kupffer cells. This signaling pathway activates mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), resulting in increased tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α expression and stability.

TLR-4-dependent signaling

Macrophages express multiple TLRs. Recent studies have demonstrated that ethanol feeding to mice increases the expression of multiple TLR mRNAs in the liver (29); however, the interaction between ethanol and TLR-4 signaling is the most well studied. TLR-4 signaling is mediated via MyD88-dependent and -independent pathways (Fig. 4) (8). Chronic ethanol feeding increases expression of TLR-4 mRNA in mouse liver after chronic ethanol exposure (27). In cellular models, changes in the expression of TLR-4 mRNA influence TLR-4-dependent responses (28); increased expression of TLR-4 likely contributes to ethanol-induced increases in TLR-4-MyD88-dependent and -independent signaling in the liver.

FIG. 4.

Chronic ethanol-induced liver injury involves MyD-88-independent signaling pathways. TLR-4 mediating signaling via MyD-88-dependent and MyD88-independent/TRIF pathways is illustrated schematically.

Ethanol and MyD88-dependent responses

Chronic ethanol exposure sensitizes Kupffer cells to TLR-4-MyD88-dependent responses, such as rapid activation of MAPKs and nuclear factor κB (NFκB), as well as TNF-α expression (2) (Fig. 3).

While LPS-mediated activation of Kupffer cells results in expression of many proinflammatory mediators, it is clear that increased TNF-α appears to be critical to the progression of ethanol-induced liver disease (104). TNF-α is a key mediator of the mammalian inflammatory response. TNF-α transduces differential signals that can mediate cellular activation, proliferation, cytotoxicity, or apoptosis. TNF-α plays important roles in mediating immuno- and hepatoprotective functions by serving as a critical component of immune function. Pharmacological or genetic manipulations that decrease TNF-α concentrations can impair the immune response (67). TNF-α is critical to normal liver regeneration, as TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1)-deficient mice have impaired hepatocyte proliferation in response to partial hepatectomy (113). However, not all of TNF-α roles are beneficial to an organism; TNF-α is associated with septic shock, inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (91), as well as the progression of ethanol-induced liver disease. Increased production of TNF-α is an early indicator of ethanol-induced liver injury, and the role of TNF-α in the progression of ethanol-induced liver disease has been extensively studied and characterized (68, 103, 104).

Macrophages, such as the Kupffer cell, are the major producers of TNF-α. TNF-α is elevated in the blood of rats (116) and humans (63) under most conditions of chronic ethanol exposure. TNFR1 is one of the surface receptors responsible for the signaling capabilities of TNF-α. TNFR1-deficient mice (116) and mice treated with polyclonal anti-mouse TNF-α rabbit serum intravenously (40) are resistant to ethanol-induced liver damage. When treated with antibiotics, rats exposed to ethanol have decreased expression of TNF-α and a lower incidence of ethanol-induced liver injury (103), suggesting that LPS contributes to increased TNF-α expression after chronic ethanol exposure. In addition to the increased exposure to LPS, chronic ethanol sensitizes Kupffer cells to TLR-4-mediated activation. This sensitivity is observed both in vivo, as chronic ethanol consumption increases the vulnerability of rats to endotoxin-induced liver injury and death (37) and in isolated Kupffer cells from rats fed an ethanol-containing diet for 4 weeks, which exhibited increased TLR-4-stimulated TNF-α expression by when compared to pair-fed controls (49, 51).

Ethanol and MyD88-independent/TRIF-dependent signaling

While the rapid LPS-stimulated expression of TNF-α is characteristic of MyD88-dependent signaling, MyD88-independent signals are more slowly activated and result in increased expression of type I interferon (IFN) and IFN-dependent genes (8). Recent studies have identified role for MyD88-independent/TIR domain-containing adaptor protein-1 (TRIF)-dependent TLR-4 signaling in the progression of ALD in mice (39, 119).

However, much less is known about the interaction between ethanol and MyD88-independent signaling in macrophages. One recent study found that, similar to the ethanol-induced sensitization of macrophages to stimulation of TNF-α, a MyD-88 signature cytokine, chronic ethanol also sensitizes mice and isolated Kupffer cells to LPS-stimulated production of IFN-β and CXCL10, two signature cytokines for TLR-4/MyD88-independent signaling (59).

Summary

Taken together, these data suggest that chronic ethanol sensitizes macrophages to both MyD88-dependent and -independent signaling pathways. Both pathways of TLR-4 signaling also likely contribute to ethanol-induced liver injury. Further studies are required to define the specific dynamics of the interactions between ethanol and signaling via these two TLR-4-mediated signaling cascades.

Interactions between redox signaling and TLR-4 during ethanol exposure.

Production of inflammatory cytokines is a highly regulated process; regulation occurs at the level of transcription, translation, and secretion (78, 111). Ethanol exposure impacts each level in the molecular regulation of TNF-α expression, resulting in an enhanced initiation of inflammation in the liver (68). Ethanol mediates these changes in the activation of Kupffer cells by a profound dysregulation in TLR-4-initiated signal transduction (68), leading to increased TNF-α transcription and mRNA stability (51, 69).

Transcriptional control of TNF-α expression

Regulation of TNF-α expression is dependent on multiple signaling cascades stimulated downstream of TLR-4. Stimulation of macrophages with LPS activates tyrosine kinases, protein kinase C, NFκB, as well as members of the MAPK family, including extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), p38, and JNK (98). Increased TNF-α transcription and stabilization of its mRNA after chronic ethanol is the consequence of multiple changes in this complex signaling network. Chronic ethanol feeding generally enhances these activation pathways, including increased LPS-stimulated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 (49, 51, 93) and NFκB activation (100). These signals are then translated into increased activity of two redox-sensitive transcription factors, p65-NFκB and early growth response-1, that are important regulators of transcription of TNF-α, as well as other inflammatory cytokines, by Kupffer cells. Chronic ethanol feeding enhances NFκB activation (100) and increases LPS-stimulated ERK1/2 activation-Egr-1 expression (64). Enhanced activation of these two signaling pathways likely contributes to increased transcription of TNF-α (119).

Regulation of TNF-α mRNA stability

In addition to the redox-sensitive signaling pathways regulating cytokine transcription, ethanol also impact signals regulating cytokine mRNA stability. The phosphorylation of p38 is closely associated with stimulus-dependent increase in TNF-α mRNA stability via phosphorylation of the protein tristetraprolin, a modulator of TNF-α mRNA stability (7, 12). By increasing p38 activation, chronic ethanol exposure also increases TNF-α mRNA stability (51). When rat Kupffer cells in culture are treated with SB203580, an inhibitor of p38 activation, ethanol-mediated stabilization of TNF-α mRNA is attenuated, demonstrating that mRNA stabilization is dependent on p38 activation (51). The stabilization of mRNA is critical to the quick, strong induction of genes involved in the inflammatory process (50). The potential interaction between redox signaling and regulation of mRNA stability is strong, given the role of ASK-1/Trx system in activation of p38 MAPK.

Ethanol and redox-sensitive TLR-4-MyD88-dependent signal transduction

Increased production of ROS during chronic ethanol exposure, by hepatocytes during ethanol metabolism (2) and/or from Kupffer cells during ethanol exposure (112) and in response to LPS (95), may contribute to the sensitization in LPS-dependent signal transduction after ethanol exposure. Redox-sensitive signaling mechanisms play a critical role in the modulation/regulation of a number of signal transduction cascades, including LPS-stimulated signaling pathways both in cells of the innate immune system (monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, etc.) and in nonimmune cells (102). Indeed, we have specifically identified NADPH oxidase-derived ROS as an important contributor to LPS-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in rat Kupffer cells, particularly after chronic ethanol (101) (Fig. 2), whereas Cao and colleagues (118) found that CYP2E1 contributes to activation of MAPK signaling in macrophages. Taken together, these data suggest that chronic ethanol-induced increases in ROS make important contributions to the dysregulation of LPS-mediated signal transduction and inflammatory cytokine production in Kupffer cells.

Ethanol-induced loss of cellular antioxidant activity and TLR-4 signal transduction

As described in Pathways Leading to Increased Reactive Oxygen in ALD section, chronic ethanol exposure has a profound impact on antioxidant functions in the liver. Recent studies suggest that restoration of antioxidant activity can normalize TLR-4-mediated responses after chronic ethanol. Treatment of primary cultures of Kupffer cells with recombinant human Trx-1 protein normalizes LPS-stimulated signal transduction via the MAPKs and NFκB. Similarly, treatment of mice with recombinant human Trx-1 reduced ethanol-induced activation of MAPK family members. This dampening of redox-sensitive signaling pathways contributed to a decrease in LPS-stimulated TNF-α expression after chronic ethanol exposure, both in vivo and in isolated Kupffer cells (14). These recent studies suggest an important link between endogenous Trx-1 expression, the effects of ethanol on Kupffer cells signaling via TLR-4 and the development of liver injury (14).

Ethanol and redox-sensitive TLR-4-MyD88-independent signaling

Given the recent evidence for a role for MyD88-independent/TRIF-dependent pathways in mediating chronic ethanol-induced liver injury (39, 119), there is a pressing need to determine if ethanol exposure also enhances LPS-stimulated signaling via TRIF-dependent cascades in a redox-sensitive mechanism. Improved understanding of the interactions between ethanol, redox signaling, and these two independent signaling cascades activated by TLR-4 is of critical importance in the design of therapeutic interventions to treat ALD.

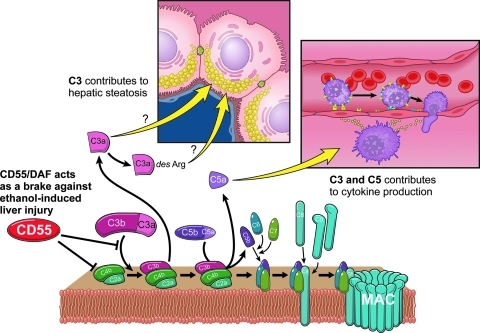

Circulating components of the innate immune system: complement and ALD

The complement cascade is a phylogenetically ancient part of our immune system critical to an organism's ability to ward off infection (27). The functions of complement can be generally grouped into three major types of activity (Fig. 5): (i) Defense against microbial infection involves the generation of lytic complexes (membrane attack complex [MAC]) on the surface of pathogens, formation of opsonins that promote phagocytosis, as well as the regulation of local pro-inflammatory responses; (ii) bridging of the innate and adaptive immune pathways; and (iii) removal of immune complexes and cellular debris that can result from inflammatory injury.

FIG. 5.

Activation and functions of complement. Complement is activated via the classical, lectin, or alternative pathways, culminating in the proteolytic cleavage of C3. Functions of complement include opsinin activity against bacteria and apoptotic cells, stimulation of inflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression, and lysis of targeted bacteria or cells.

Complement activation pathways.

Activation of the complement pathway can occur via the classical, lectin, or alternative pathways; all three pathways culminate in the activation of C3 (Figs. 1 and 5). These pathways leading to C3 cleavage are “triggered enzyme cascades,” analogous to the regulated activation of the coagulation pathway (109). C1q is the central protein in the classical pathway. Binding of C1q to IgG- or IgM-containing immune complexes results in the autoactivation of C1q as a result of a conformational change in the collagen region of C1q (52). C1q can also be activated by binding to microbial ligands, as well as apoptotic cell surface components (24). The lectin pathway is initiated by the binding of mannose binding protein (mannose binding lectin [MBL])/ficolin to carbohydrate moieties on surfaces of various pathogens. Activation of the initial steps in both the classical and lectin pathways leads to the cleavage of C4 and C2 to form C4bC2a, which acts as a C3 convertase to cleave C3 (25). The alternative pathway is activated by a diverse array of surfaces and substances, including bacterial and yeast cell walls, LPS, and cobra venom (25), leading to a low-grade cleavage of C3. C3b generated in this cleavage reaction forms a complex with factor B, C3bBb, which acts as a C3 convertase, allowing for further accelerating cleavage of C3 (25, 108).

Functions of complement: anaphylatoxins, opsonins, and MAC and redox signaling.

All three pathways of complement activation converge at the point of C3 cleavage. The cleavage products C3a and C5a, termed the anaphylatoxins, are important regulators of the inflammatory response. Kupffer cells express receptors for both C3a and C5a (92), and exposure of Kupffer cells to C5a results in the rapid production of prostanoids and inflammatory cytokines (92), either alone or in the presence of other inflammatory mediators, such as LPS (92). C3a can activate the respiratory burst, eliciting rapid Ca+2 transients and generating potentially injurious ROS (22, 23). C5a is particularly critical in mediating a pro-inflammatory response, as it functions as a chemotactic agent, recruiting neutrophils to the site of infection/injury by regulating the expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules (19, 43).

The C3 cleavage products C3b and iC3b act as opsonins, promoting the phagocytosis of bacterial particles by macrophages expressing complement receptors (CR1, CR3, or CR4). C3b also joins the C3bBb and C4bC2a convertases to form a C5 convertase activity (5). Cleavage of C5 is the first step in the further targeted enzymatic cleavage of complement proteins involved in the formation of the MAC, which is comprised of C5b, C6, C7, C8, and multiple C9 molecules. These proteins assemble into a pore/hole in the phospholipid bilayer, leading to cell lysis (27). Formation of a sublytic MAC initiates a variety of redox-regulated signaling pathways, including Ras and Raf-1, as well as MAPKs and PI3 kinase (75).

Intrinsic complement regulatory proteins.

Given the powerful nature of the complement pathway, several mechanisms have evolved for self-protection of the host organism from destruction by this pathway (5). A number of soluble complement inhibitors are secreted, including C1 inhibitor (C1-INH), C4b binding protein, factor H, and factor I. Cells also express membrane-associated inhibitors (e.g., CD46, decay accelerating factor [DAF]/CD55, and CD59). Each complement regulatory protein counters specific activation steps or formation of the MAC (5).

Complement and the liver.

The liver plays essential functions in the complement system, acting as the primary site of production and secretion of circulating complement proteins. Cells in the liver also express CRs and intrinsic regulatory proteins. In healthy liver, Kupffer cells and stellate cells express both C3a and C5a receptor; C5a receptor expression can be induced in hepatocytes in response to inflammatory cytokines (92) or in regenerating hepatocytes (17). While the liver is exposed to complement proteins, as well as activated complexes, it is resistant to complement-induced lysis (53, 54). This protection likely involves the activity of intrinsic complement regulatory proteins, since CD55/DAF and CD59 are expressed by hepatocytes (30, 53), hepatic endothelial cells (58), and Kupffer cells (Stavitsky and Nagy, unpublished observations). Further, resistance of hepatocytes to complement-mediated injury also depends on phosphoinositol-3 kinase/Akt signaling (53).

Complement has hepatoprotective activity in liver, but also contributes to the progression of liver injury. For example, C3 and C5 are required for hepatocyte proliferation in response to toxin-induced injury and partial hepatectomy (60, 61, 96). This “Jekyll-Hyde” role of complement is similar to the dual role of a number of innate immune mediators and acute-phase proteins in mediating both injury and protection in the liver, with the dual role of TNF-α being the classically studied example [see (81) for a discussion of this issue]. Interestingly, mice lacking C3 and C5 are differentially protected against ethanol-induced increases in hepatic triglycerides and circulating ALT, respectively (Fig. 6) (9, 82). Conversely, mice lacking CD55/DAF, a complement regulatory protein, have exacerbated liver injury compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 6) (82). In rats, chronic ethanol exposure increases C3 activity and decreases expression of Crry, the rat homolog of CD55/DAF, and CD59 in the liver (42). Additionally, rats deficient in complement component 6 (C6), a protein that makes up part of the MAC, have increased hepatic steatosis and inflammation compared to wild-type controls (10). After 4 days or 4 weeks of ethanol feeding to mice, complement is activated with increases in circulating C3a (82), as well as C3b deposition in the liver (9, 90). Complement activation products then interact with C3a receptor and C5aR to increase TNF-α expression (90). Ethanol-mediated complement activation is dependent on C1q, a protein of the classical pathway (15). Complement also likely contributes to other types of liver injury, as a recent study detected products of complement activation in liver of patients with NAFLD/NASH (85).

FIG. 6.

Complement contributes to ethanol-induced liver injury in mice. C3 and C5 contribute to ethanol-induced increases in hepatic triglycerides and circulating alanine aminotransferease, respectively; CD55/decay accelerating factor (DAF), a complement regulatory protein, acts as a brake against ethanol-induced inflammation and liver injury.

Summary: Interactions Between Redox Signaling and Innate Immunity During Ethanol Exposure

The innate immune system is designed to rapidly respond to both endogenous and exogenous stresses, including infections, trauma, and toxins. It has long been appreciated that ROS contribute to the regulation of cellular signal transduction (102). Studies focusing on the role of ethanol-induced oxidative stress and aberrant TLR-4-dependent signal transduction have identified a key interaction between redox signaling and the expression of inflammatory cytokines in the liver and other tissues (68, 107). In addition to the interaction between redox signaling and TLR-4-mediated responses, there is a growing appreciation for the interactions between oxidative stress and activation of complement, stemming primarily from studies of macular degeneration and ischemia-reperfusion injury (34, 35). The mechanisms for complement activation during ethanol exposure are not well understood; however, it appears likely that ethanol-induced oxidative stress is intimately linked to activation of complement, as well as to the cellular response to the products of complement activation. The available data indicate that early ethanol-induced increases in inflammatory cytokines are dependent on complement activation (15); these early increases in cytokine expression contribute to subsequent oxidative stress in the liver and the progression of ethanol-induced liver injury (90). It is also likely that the interaction of ethanol metabolism and redox signaling in the liver contribute to complement activation, resulting in a feed-forward mechanism for exacerbation of injury during ethanol exposure.

Abbreviations Used

- ADH

alcohol dehydrogenase

- ALD

alcoholic liver disease

- ASK-1

apoptosis signal-regulating kinase-1

- BHMT

betaine homocysteine methyltransferase

- CR

complement receptor

- CYP2E1

cytochrome P450 2E1

- DAF

decay accelerating factor

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione

- IFN

interferon

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LBP

LPS-binding protein

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MAC

membrane attack complex

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MBL

mannose binding lectin

- MEOS

microsomal ethanol oxidizing system

- MS

methionine synthase

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- NFκB

nuclear factor κB

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SAH

S-adenosyl homocysteine

- SAM

S-adenosyl methionine

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- THF

tetrahydrofolate

- TLR-4

toll-like receptor-4

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TNFR1

TNF receptor 1

- TRIF

TIR domain-containing adaptor protein-1

- Trx

thioredoxin

- TrxR

thioredoxin reductase

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Schumick for original artwork. This work was supported in part by F31 AA016434 JIC and RO1AA11975, RO1AA16399, and P20AA017069 to L.E.N.

References

- 1.Adachi Y. Bradford BU. Gao W. Bojes HK. Thurman RG. Inactivation of Kupffer cells prevents early alcohol-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 1994;20:453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arteel GE. Oxidants and antioxidants in alcohol-induced liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:778–790. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balkan J. Parldar FH. Dogru-Abbasoglu S. Aykac-Toker G. Uysal M. The effect of taurine or betaine pretreatment on hepatotoxicity and prooxidant status induced by lipopolysaccharide treatment in the liver of rats. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:917–921. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bode JC. Bode G. Heidelbach R. Durr HK. Martini GA. Jejunal microflora in patients with chronic alcohol abuse. Hepatogastroenterology. 1984;31:30–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohana-Kashtan O. Ziporen L. Donin N. Kraus S. Fishelson Z. Cell signals transduced by complement. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:583–597. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouckenooghe T. Remacle C. Reusens B. Is taurine a functional nutrient? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9:728–733. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000247469.26414.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brook M. Sully G. Clark AR. Saklatvala J. Regulation of tumour necrosis factor alpha mRNA stability by the mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 signalling cascade. FEBS Lett. 2000;483:57–61. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke-Gaffney A. Callister ME. Nakamura H. Thioredoxin: friend or foe in human disease? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bykov I. Jauhiainen M. Olkkonen VM. Saarikoski ST. Ehnholm C. Junnikkala S. Vakeva A. Lindros KO. Meri S. Hepatic gene expression and lipid parameters in complement C3(−/−) mice that do not develop ethanol-induced steatosis. J Hepatol. 2007;46:907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bykov IL. Vakeva A. Jarvelainen HA. Meri S. Lindros KO. Protective function of complement against alcohol-induced rat liver damage. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4:1445–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao Q. Mak KM. Lieber CS. Cytochrome P4502E1 primes macrophages to increase TNF-alpha production in response to lipopolysaccharide. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:G95–G107. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00383.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carballo E. Cao H. Lai WS. Kennington EA. Campbell D. Blackshear PJ. Decreased sensitivity of tristetraprolin-deficient cells to p38 inhibitors suggests the involvement of tristetraprolin in the p38 signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42580–42587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104953200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X. Sebastian BM. Tang H. McMullen MM. Axhemi A. Jacobsen DW. Nagy LE. Taurine supplementation prevents ethanol-induced decrease in serum adiponectin and reduces hepatic steatosis in rats. Hepatology. 2009;49:1554–1562. doi: 10.1002/hep.22811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen JI. Roychowdhury S. DiBello PM. Jacobsen DW. Nagy LE. Exogenous thioredoxin prevents ethanol-induced oxidative damage and apoptosis in mouse liver. Hepatology. 2009;49:1710–1719. doi: 10.1002/hep.22837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen JI. Roychowdhury S. McMullen MR. Stavitsky AB. Nagy LE. Complement and alcoholic liver disease: role of C1q in the pathogenesis of ethanol-induced liver injury in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:664–674. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colell A. Gargía-Ruiz C. Miranda M. Ardite E. Marí M. Morales A. Corrales F. Kaplowitz N. Fernández-Checa JC. Selective glutathione depletion of mitochondria by ethanol sensitizes hepatocytes to tumor necrosis factor. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1541–1551. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daveau M. Benard M. Scotte M. Schouft MT. Hiron M. Francois A. Salier JP. Fontaine M. Expression of a functional C5a receptor in regenerating hepatocytes and its involvement in a proliferative signaling pathway in rat. J Immunol. 2004;173:3418–3424. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dey A. Cederbaum AI. Alcohol and oxidative liver injury. Hepatology. 2006;43:S63–S74. doi: 10.1002/hep.20957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiScipio RG. Daffern PJ. Jagels MA. Broide DH. Sriramarao P. A comparison of C3a and C5a-mediated stable adhesion of rolling eosinophils in postcapillary venules and transendothelial migration in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;162:1127–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ekstrom G. Ingelman-Sundberg M. Rat liver microsomal NADPH-supported oxidase activity and lipid peroxidation dependent on ethanol-inducible cytochrome P-450 (P-450IIE1) Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38:1313–1319. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90338-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eliasson E. Mkrtchian S. Ingelman-Sundberg M. Hormone- and substrate-regulated intracellular degradation of cytochrome P450 (2E1) involving MgATP-activated rapid proteolysis in the endoplasmic reticulum membranes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15765–15769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elsner J. Oppermann M. Czech W. Dobos G. Schopf E. Norgauer J. Kapp A. C3a activates reactive oxygen radical species production and intracellular calcium transients in human eosinophils. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:518–522. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elsner J. Oppermann M. Czech W. Kapp A. C3a activates the respiratory burst in human polymorphonuclear neutrophilic leukocytes via pertussis toxin-sensitive G-proteins. Blood. 1994;83:3324–3331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elward K. Griffiths M. Mizuno M. Harris CL. Neal JW. Morgan BP. Gasque P. CD46 plays a key role in tailoring innate immune recognition of apoptotic and necrotic cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36342–36354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506579200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujita T. Evolution of the lectin-complement pathway and its role in innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:346–353. doi: 10.1038/nri800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukui H. Brauner B. Bode J. Bode C. Plasma endotoxin concentrations in patients with alcoholic and nonalcoholic liver disease: reevaluation with an improved chromogenic assay. J Hepatol. 1991;12:162–169. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90933-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gasque P. Complement: a unique innate immune sensor for danger signals. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:1089–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gressner AM. Bachem MG. Molecular mechanisms of liver fibrogenesis-a homage to the role of activated fat-storing cells. Digestion. 1995;56:335–346. doi: 10.1159/000201257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gustot T. Lemmers A. Moreno C. Nagy N. Quertinmont E. Nicaise C. Franchimont D. Louis H. Deviere J. Le Moine O. Differential liver sensitization to toll-like receptor pathways in mice with alcoholic fatty liver. Hepatology. 2006;43:989–1000. doi: 10.1002/hep.21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halme J. Sachse M. Vogel H. Giese T. Klar E. Kirschfink M. Primary human hepatocytes are protected against complement by multiple regulators. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:2284–2289. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamilton EJ. Berg HM. Easton CJ. Bakker AJ. The effect of taurine depletion on the contractile properties and fatigue in fast-twitch skeletal muscle of the mouse. Amino Acids. 2006;31:273–278. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansen SH. The role of taurine in diabetes and the development of diabetic complications. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2001;17:330–346. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harada C. Nakamura K. Namekata K. Okumura A. Mitamura Y. Iizuka Y. Kashiwagi K. Yoshida K. Ohno S. Matsuzawa A. Tanaka K. Ichijo H. Harada T. Role of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in stress-induced neural cell apoptosis in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:261–269. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hart ML. Walsh MC. Stahl GL. Initiation of complement activation following oxidative stress. In vitro and in vivo observations. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hollyfield JG. Bonilha VL. Rayborn ME. Yang X. Shadrach KG. Lu L. Ufret RL. Salomon RG. Perez VL. Oxidative damage-induced inflammation initiates age-related macular degeneration. Nat Med. 2008;14:194–198. doi: 10.1038/nm1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmgren A. Lu J. Thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase: current research with special reference to human disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Honchel R. Marsono L. Cohen D. Shedlofsky S. McClain C. A role for tumor necrosis factor in alcohol enhanced endotoxin liver injury. In: Dinarello CA, editor; Kluger MJ, editor; Powanda MC, editor; Oppenheim JJ, editor. The Physiological and Pathological Effects of Cytokines. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1990. pp. 171–176. 10B. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoshiai M. Hattan N. Hirota Y. Hoshiai K. Ishida H. Nakazawa H. Impaired sarcoplasmic reticulum function in lipopolysaccharide- induced myocardial dysfunction demonstrated in whole heart. Shock. 1999;11:362–366. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199905000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hritz I. Mandrekar P. Velayudham A. Catalano D. Dolganiuc A. Kodys K. Kurt-Jones E. Szabo G. The critical role of toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 in alcoholic liver disease is independent of the common TLR adapter MyD88. Hepatology. 2008;48:1224–1231. doi: 10.1002/hep.22470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iimuro Y. Gallucci RM. Luster MI. Kono H. Thurman RG. Antibodies to tumor necrosis factor alfa attenuate hepatic necrosis and inflammation caused by chronic exposure to ethanol in the rat. Hepatology. 1997;26:1530–1537. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishii T. Sunami O. Saitoh N. Nishio H. Takeuchi T. Hata F. Inhibition of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+- ATPase by nitric oxide. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:218–222. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01460-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jarvelainen HA. Vakeva A. Lindros KO. Meri S. Activation of complement components and reduced regulator expression in alcohol-induced liver injury in the rat. Clin Immunol. 2002;105:57–63. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jauneau AC. Ischenko A. Chan P. Fontaine M. Complement component anaphylatoxins upregulate chemokine expression by human astrocytes. FEBS Lett. 2003;537:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ji C. Kaplowitz N. Betaine decreases hyperhomocysteinemia, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and liver injury in alcohol-fed mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1488–1499. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kalinina EV. Chernov NN. Saprin AN. Involvement of thio-, peroxi-, and glutaredoxins in cellular redox-dependent processes. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2008;73:1493–1510. doi: 10.1134/s0006297908130099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keshavarzian A. Farhadi A. Forsyth CB. Rangan J. Jakate S. Shaikh M. Banan A. Fields JZ. Evidence that chronic alcohol exposure promotes intestinal oxidative stress, intestinal hyperpermeability and endotoxemia prior to development of alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. J Hepatol. 2009;50:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kessova I. Cederbaum AI. CYP2E1: biochemistry, toxicology, regulation and function in ethanol-induced liver injury. Curr Mol Med. 2003;3:509–518. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kessova IG. Ho YS. Thung S. Cederbaum AI. Alcohol-induced liver injury in mice lacking Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase. Hepatology. 2003;38:1136–1145. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kishore R. Hill JR. McMullen MR. Frenkel J. Nagy LE. ERK1/2 and Egr-1 contribute to increased TNFα production in rat Kupffer cells after chronic ethanol feeding. Am J Phys. 2002;282:G6–G15. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00328.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kishore R. McMullen MR. Cocuzzi E. Nagy LE. Stabilization of TNFα mRNA contributes to increased lipopolysaccharide-stimulated TNFα production by Kupffer Cells after chronic ethanol feeding. Comp Hepatol. 2004;3:S31. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-2-S1-S31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kishore R. McMullen MR. Nagy LE. Stabilization of TNFα mRNA by chronic ethanol: role of A+U rich elements and p38 mitogen activated protein kinase signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41930–41937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kishore U. Gaboriaud C. Waters P. Shrive AK. Greenhough TJ. Reid KB. Sim RB. Arlaud GJ. C1q and tumor necrosis factor superfamily: modularity and versatility. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:551–561. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koch CA. Kanazawa A. Nishitai R. Knudsen BE. Ogata K. Plummer TB. Butters K. Platt JL. Intrinsic resistance of hepatocytes to complement-mediated injury. J Immunol. 2005;174:7302–7309. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koch N. Jung M. Sabat R. Kratzschmar J. Docke WD. Asadullah K. Volk HD. Grutz G. IL-10 protects monocytes and macrophages from complement-mediated lysis. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:155–166. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0708443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lambert JC. Zhou Z. Wang L. Song Z. McClain CJ. Kang YJ. Prevention of alterations in intestinal permeability is involved in zinc inhibition of acute ethanol-induced liver damage in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:880–886. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.047852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lieber CS. Alcohol and the liver: 1994 update. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1085–1105. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lieber CS. Alcoholic liver disease: new insights in pathogenesis lead to new treatments. J Hepatol. 2000;32(Suppl. 1):113–128. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin F. Fukuoka Y. Spicer A. Ohta R. Okada N. Harris CL. Emancipator SN. Medof ME. Tissue distribution of products of the mouse decay-accelerating factor (DAF) genes. Exploitation of a Daf1 knock-out mouse and site-specific monoclonal antibodies. Immunology. 2001;104:215–225. doi: 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mandal P. Roychowdhury S. Park P-H. Pratt BT. Roger T. Nagy LE. Adiponectin and heme oxygenase-1 suppress TLR4/MyD88-independent signalling in rat Kupffer cells and in mice after chronic ethanol exposure. J Immunol. 2010;185:4928–4937. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Markiewski MM. Mastellos D. Tudoran R. DeAngelis RA. Strey CW. Franchini S. Wetsel RA. Erdei A. Lambris JD. C3a and C3b activation products of the third component of complement (C3) are critical for normal liver recovery after toxic injury. J Immunol. 2004;173:747–754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mastellos D. Papadimitriou JC. Franchini S. Tsonis PA. Lambris JD. A novel role of complement: mice deficient in the fifth component of complement (C5) exhibit impaired liver regeneration. J Immunol. 2001;166:2479–2486. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mato JM. Lu SC. Role of S-adenosyl-L-methionine in liver health and injury. Hepatology. 2007;45:1306–1312. doi: 10.1002/hep.21650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McClain CJ. Cohen DA. Increased tumor necrosis factor production by monocytes in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 1989;9:349–351. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McMullen MR. Pritchard MT. Wang Q. Millward CA. Croniger CM. Nagy LE. Early growth response-1 transcription factor is essential for ethanol-induced Fatty liver injury in mice. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:2066–2076. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Militante JD. Lombardini JB. Treatment of hypertension with oral taurine: experimental and clinical studies. Amino Acids. 2002;23:381–393. doi: 10.1007/s00726-002-0212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Minagawa M. Deng Q. Liu ZX. Tsukamoto H. Dennert G. Activated natural killer T cells induce liver injury by Fas and tumor necrosis factor-alpha during alcohol consumption. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1387–1399. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mohammed FF. Smookler DS. Taylor SE. Fingleton B. Kassiri Z. Sanchez OH. English JL. Matrisian LM. Au B. Yeh WC. Khokha R. Abnormal TNF activity in Timp3−/− mice leads to chronic hepatic inflammation and failure of liver regeneration. Nat Genet. 2004;36:969–977. doi: 10.1038/ng1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nagy LE. New insights into the role of the innate immune response in the development of alcoholic liver disease. Exp Biol Med. 2003;228:882–890. doi: 10.1177/153537020322800803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nagy LE. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol metabolism. Ann Rev Nutr. 2004;24:55–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakamura H. Herzenberg LA. Bai J. Araya S. Kondo N. Nishinaka Y. Herzenberg LA. Yodoi J. Circulating thioredoxin suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced neutrophil chemotaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15143–15148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191498798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nakamura H. Mitsui A. Yodoi J. Thioredoxin overexpression in transgenic mice. Methods Enzymol. 2002;347:436–440. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)47043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nanji AA. Greenberg SS. Tahan SR. Fogt F. Loscalzo J. Sadrzadeh SMH. Xie J. Stamler JS. Nitric oxide production in experimental alcoholic liver disease in the rat: role in protection from injury. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:899–907. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90400-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nanji AA. Khettry U. Sadrzadeh SM. Lactobacillus feeding reduces endotoxemia and severity of experimental alcoholic liver (disease) Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1994;205:243–247. doi: 10.3181/00379727-205-43703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nanji AA. Miao L. Thomas P. Rahemtulla A. Khwaja S. Zhao S. Peters D. Tahan SR. Dannenberg AJ. Enhanced cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in alcoholic liver disease in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:943–951. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Niculescu F. Rus H. Mechanisms of signal transduction activated by sublytic assembly of terminal complement complexes on nucleated cells. Immunol Res. 2001;24:191–199. doi: 10.1385/ir:24:2:191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nordmann R. Ribiere C. Rouach H. Implication of free radical mechanisms in ethanol-induced cellular injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992;12:219–240. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90030-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Osna NA. Hepatitis C virus and ethanol alter antigen presentation in liver cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1201–1208. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Papadakis KA. Targan SR. Tumor necrosis factor: biology and therapeutic inhibitors. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1148–1157. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.18160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Perez MJ. Cederbaum AI. Antioxidant and pro-oxidant effects of a manganese porphyrin complex against CYP2E1-dependent toxicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:111–127. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00865-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Powell CL. Bradford BU. Craig CP. Tsuchiya M. Uehara T. O'Connell TM. Pogribny IP. Melnyk S. Koop DR. Bleyle L. Threadgill DW. Rusyn I. Mechanism for prevention of alcohol-induced liver injury by dietary methyl donors. Toxicol Sci. 2010;115:131–139. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pritchard MT. Cohen JI. Roychowdhury S. Pratt BT. Nagy LE. Early growth response-1 attenuates liver injury and promotes hepatoprotection after carbon tetrachloride exposure in mice. J Hepatol. 2010;53:655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pritchard MT. McMullen MR. Stavitsky AB. Cohen JI. Lin F. Medof ME. Nagy LE. Differential contributions of C3, C5, and decay-accelerating factor to ethanol-induced fatty liver in mice. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1117–1126. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rao R. Endotoxemia and gut barrier dysfunction in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;50:638–644. doi: 10.1002/hep.23009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rashba-Step J. Turro NJ. Cederbaum AI. Increased NADPH- and NADH-dependent production of superoxide and hydroxyl radical by microsomes after chronic ethanol treatment. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300:401–408. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rensen SS. Slaats Y. Driessen A. Peutz-Kootstra CJ. Nijhuis J. Steffensen R. Greve JW. Buurman WA. Activation of the complement system in human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;50:1809–1817. doi: 10.1002/hep.23228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roberts BJ. Song BJ. Soh Y. Park SS. Shoaf SE. Ethanol induces CYP2E1 by protein stabilization. Role of ubiquitin conjugation in the rapid degradation of CYP2E1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29632–29635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.29632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roede JR. Orlicky DJ. Fisher AB. Petersen DR. Overexpression of peroxiredoxin 6 does not prevent ethanol-mediated oxidative stress and may play a role in hepatic lipid accumulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;330:79–88. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.152983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Roede JR. Stewart BJ. Petersen DR. Decreased expression of peroxiredoxin 6 in a mouse model of ethanol consumption. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:1551–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ronis MJ. Butura A. Sampey BP. Shankar K. Prior RL. Korourian S. Albano E. Ingelman-Sundberg M. Petersen DR. Badger TM. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats fed via total enteral nutrition. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:619–630. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Roychowdhury S. McMullen MR. Pritchard MT. Hise AG. van Rooijen N. Medof ME. Stavitsky AB. Nagy LE. An early complement-dependent and TLR-4-independent phase in the pathogenesis of ethanol-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology. 2009;49:1326–1334. doi: 10.1002/hep.22776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sacre SM. Andreakos E. Taylor P. Feldmann M. Foxwell BM. Molecular therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2005;7:1–20. doi: 10.1017/S1462399405009488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schieferdecker HL. Schlaf G. Jungermann K. Gotze O. Functions of anaphylatoxin C5a in rat liver: direct and indirect actions on nonparenchymal and parenchymal cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:469–481. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(00)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shi L. Kishore R. McMullen M. Nagy LE. Lipopolysaccharide stimulation of ERK1/2 increases TNFα production via Egr-1. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:C1205–C1211. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00511.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shi QZ. Wang LW. Zhang W. Gong ZJ. Betaine inhibits toll-like receptor 4 expression in rats with ethanol-induced liver injury. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:897–903. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i7.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Spolarics Z. Endotoxemia, pentose cycle, and the oxidant/antioxidant balance in the hepatic sinusoid. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:534–541. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.5.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Strey CW. Markiewski M. Mastellos D. Tudoran R. Spruce LA. Greenbaum LE. Lambris JD. The proinflammatory mediators C3a and C5a are essential for liver regeneration. J Exp Med. 2003;198:913–923. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Su GL. Goyert SM. Fan MH. Aminlari A. Gong KQ. Klein RD. Myc A. Alarcon WH. Steinstraesser L. Remick DG. Wang SC. Activation of human and mouse Kupffer cells by lipopolysaccharide is mediated by CD14. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G640–G645. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00253.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sweet MJ. Hume DA. Endotoxin signal transduction in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:8–26. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sykora P. Kharbanda KK. Crumm SE. Cahill A. S-adenosyl-L-methionine co-administration prevents the ethanol-elicited dissociation of hepatic mitochondrial ribosomes in male rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Szabo G. Dolganiuc A. Catalano D. Kodys K. Mandrakar P. Opposite regulation of monocyte activation by acute and prolonged alcohol occurs at multiple levels of TLR4 signaling. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:273A. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Thakur V. Pritchard MT. McMullen MR. Wang Q. Nagy LE. Chronic ethanol feeding increases activation of NADPH oxidase by lipopolysaccharide in rat Kupffer cells: role of increased reactive oxygen in LPS-stimulated ERK1/2 activation and TNF-alpha production. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:1348–1356. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1005613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Thannickal VJ. Fanburg BL. Reactive oxygen species in cell signaling. Am. J. Physiol. 2000;279:L1005–L1028. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Thurman RG. Mechanisms of Hepatic Toxicity II. Alcoholic liver injury involves activation of Kupffer cells by endotoxin. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G605–G611. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.4.G605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tilg H. Diehl AM. Cytokines in alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1467–1476. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011163432007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Uesugi T. Froh M. Arteel GE. Bradford BU. Thurman RG. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in the mechanism of early alcohol-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology. 2001;34:101–108. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Varatharajalu R. Garige M. Leckey LC. Gong M. Lakshman MR. Betaine protects chronic alcohol and omega-3 PUFA-mediated down-regulations of PON1 gene, serum PON1 and homocysteine thiolactonase activities with restoration of liver GSH. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:424–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Vidali M. Stewart SF. Albano E. Interplay between oxidative stress and immunity in the progression of alcohol-mediated liver injury. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vukajlovich SW. Interaction of LPS with serum complement. In: Ryan JL, editor; Morrison DC, editor. Bacterial Endotoxic Lipopolysaccharides. Boca Raton FL: CRC Press; 1992. pp. 215–235. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Walport MJ. Complement. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1058–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wang YZ. Zhang P. Rice AB. Bonner JC. Regulation of interleukin-1β-induced platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α expression in rat pulmonary myofibroblasts by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22550–22557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909785199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Watkins LR. Hansen MK. Nguyne KT. Lee JE. Maier SF. Dynamic regulation of the proinflammatory cytokine, interleukin-1β. Life Sci. 1999;65:449–481. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wheeler MD. Kono H. Yin M. Nakagami M. Uesugi T. Arteel GE. Gabele E. Rusyn I. Yamashina S. Froh M. Adachi Y. Iimuro Y. Bradford BU. Smutney OM. Connor HD. Mason RP. Goyert SM. Peters JM. Gonzalez FJ. Samulski RJ. Thurman RG. The role of Kupffer cell oxidant production in early ethanol-induced liver disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:1544–1549. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00748-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yamada Y. Kiriloova I. Peschon II. Fausto N. Initiation of liver growth by tumor necrosis factor: deficient liver regeneration in mice lacking type I TNFα receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1441–1446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yilmaz H. Sahin S. Sayar N. Tangurek B. Yilmaz M. Nurkalem Z. Onturk E. Cakmak N. Bolca O. Effects of folic acid and N-acetylcysteine on plasma homocysteine levels and endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease. Acta Cardiol. 2007;62:579–585. doi: 10.2143/AC.62.6.2024017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yin M. Bradford BU. Wheeler MD. Uesugi T. Froh M. Goyert SM. Thurman RG. Reduced early alcohol-induced liver injury in CD14-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:4737–4742. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yin M. Wheeler MD. Kono H. Bradford BU. Gallucci RM. Luster MI. Thurman RG. Essential role of tumor necrosis factor a in alcohol-induced liver injury in mice. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:942–952. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Young TA. Bailey SM. Van Horn CG. Cunningham CC. Chronic ethanol consumption decreases mitochondrial and glycolytic production of ATP in liver. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:254–260. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yu S. Matsusue K. Kashireddy P. Cao WQ. Yeldandi V. Yeldandi AV. Rao MS. Gonzalez FJ. Reddy JK. Adipocyte-specific gene expression and adipogenic steatosis in the mouse liver due to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma1 (PPARgamma1) overexpression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:498–505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhao XJ. Dong Q. Bindas J. Piganelli JD. Magill A. Reiser J. Kolls JK. TRIF and IRF-3 binding to the TNF promoter results in macrophage TNF dysregulation and steatosis induced by chronic ethanol. J Immunol. 2008;181:3049–3056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]