Abstract

Metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors play important roles in the modulation of nociception. Previous studies demonstrated that mGlu5 modulates nociceptive plasticity via activation of ERK signaling. We have reported recently that the Kv4.2 K+ channel subunit underlies A-type currents in spinal cord dorsal horn neurons and that this channel is modulated by mGlu5-ERK signaling. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that modulation of Kv4.2 by mGlu5 occurs in excitatory spinal dorsal horn neurons. With the use of a transgenic mouse strain expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) under control of the promoter for the γ-amino butyric acid (GABA)-synthesizing enzyme, glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 (GAD67), we found that these GABAergic neurons express less Kv4.2-mediated A-type current than non-GAD67-GFP neurons. Furthermore, the mGlu1/5 agonist, (R,S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine, had no modulatory effects on A-type currents or neuronal excitability in this subgroup of GABAergic neurons but robustly modulated A-type currents and neuronal excitability in non-GFP-expressing neurons. Immunofluorescence studies revealed that Kv4.2 was highly colocalized with markers of excitatory neurons, such as vesicular glutamate transporter 1/2, PKCγ, and neurokinin 1, in cultured dorsal horn neurons. These results indicate that mGlu5-Kv4.2 signaling is associated with excitatory dorsal horn neurons and suggest that the pronociceptive effects of mGlu5 activation in the spinal cord likely involve enhanced excitability of excitatory neurons.

Keywords: pain; nociception; central sensitization; spinal cord; glutamate decarboxylase GAD67; protein kinase C γ; 3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine; vesicular glutamate transport; neurokinin-1 receptor

the dynamic balance between inhibition and excitation is fundamental in determining information transfer through neuronal circuits. The spinal cord superficial dorsal horn is a critical site of modulation for pain transmission. Alterations to spinal network activity, for instance, excess excitation, or deficient inhibition in the spinal dorsal horn network are thought to contribute to the development of pathological pain (Baba et al. 2003; Kuner 2010; Takazawa and MacDermott 2010; Torsney and MacDermott 2006). Because of the important role of ion channel modulation by receptors and signaling molecules in regulating these neuronal circuits, it is important to understand the functional role of receptors and ion channels in spinal cord dorsal horn networks.

Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGlu1 and mGlu5) have been implicated as mediators of nociceptive plasticity. Activation of mGlu1/5 leads to activation of the ERKs and induces pain hypersensitivity (Karim et al. 2001). mGlu5 is robustly expressed in the superficial dorsal horn (Karim et al. 2001; Li et al. 2010; Pitcher et al. 2007), and we have shown that Kv4.2 is a downstream target of mGlu5-ERK signaling (Hu et al. 2007). Kv4.2 is also strongly expressed in the spinal cord dorsal horn and highly colocalized with mGlu5 (Hu et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2005). The superficial lamina of the spinal cord contain both excitatory and inhibitory neurons, and excitatory neurons can be projection neurons or interneurons (Baba et al. 1998; Brumovsky et al. 2007; Dougherty et al. 2005, 2009; Heinke et al. 2004; Persson et al. 2006; Yasaka et al. 2010). Because we do not know the transmitter phenotype of the neurons, from which we recorded in our previously published studies (Hu et al. 2007), the specific cellular circuitry impacted by these signaling pathways remains to be determined. In this study, we used transgenic mice expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 (GAD67) promoter (GAD67-GFP mice) (Oliva et al. 2000) and compared expression of Kv4.2 in GAD67-GFP and non-GFP neurons using immunostaining and patch-clamp techniques. We show that these γ-amino butyric acid (GABA)ergic neurons express little or no Kv4.2-mediated currents relative to non-GAD67-GFP neurons. Furthermore, Kv4.2 is mostly colocalized with neurochemical markers for excitatory neurons in the spinal cord dorsal horn. Our data suggest that Kv4.2 is predominantly expressed in excitatory neurons and that the pronociceptive effects of mGlu5 activation in the spinal cord likely involve enhanced excitability of excitatory neurons.

METHODS

Animals.

All experiments were done in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and The International Association for the Study of Pain and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington University School of Medicine (St. Louis, MO). Homozygotic GAD67-GFP [GFP-expressing inhibitory neurons (GIN)] friend virus B-type (FVB) mice, which express enhanced GFP under control of the promoter for the GABA-synthesizing enzyme GAD67 (Oliva et al. 2000), and wild-type FVB mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA).

Cell culture.

Primary cultures of spinal cord superficial dorsal horn neurons were prepared from 3- to 5-day-old GIN or wild-type FVB mouse pups, as previously described (Hu and Gereau 2003; Hu et al. 2003). Twelve cultures were made for electrophysiology recordings, and 10 cultures were used for double-staining.

Electrophysiological recording.

Standard whole-cell recordings were made at room temperature using an EPC10 amplifier and Pulse version 8.62 software (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany) as previously described (Hu and Gereau 2003; Hu et al. 2003). Electrode resistances were 3–6 MΩ with series resistances of 6–15 MΩ, which were compensated >60%. Only neurons with a resting membrane potential more hyperpolarized than −50 mV were used. All neurons had leak currents <100 pA (at −80 mV), which were not subtracted online. Access resistance and input resistance were monitored by hyperpolarizing current injection throughout the course of the experiment. The data were rejected if either of these parameters changed >20%.

For voltage-clamp recordings in cultured neurons, the bath solution was HBSS containing 500 nM TTX and 2 mM CoCl2 to block voltage-gated Na+ currents and Ca2+ currents. The electrode solution contained (in mM) 140 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 3 Na2ATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, pH 7.4. The membrane voltage was held at −80 mV, and transient potassium currents (IA) were isolated by a two-step voltage protocol as previously described (Hu and Gereau 2003; Hu et al. 2003). Briefly, a total outward current was evoked by a command potential of +40 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV. The A-type current was dissected away from the sustained current by the voltage protocol (a 150-ms prepulse to −10 mV allowed the transient channels to inactivate, leaving only the sustained current). Subtraction of the sustained current from the total current isolated the A-type current. With the use of this protocol, if the subtraction current is ≥200 pA or the A-type current density is ≥50 pA/pF, it is considered as an A-type current. To determine the voltage dependence of activation, voltage steps of 500 ms were applied at 5-s intervals in +10-mV increments from −80 mV to a maximum of +70 mV. To determine the voltage dependence of inactivation, conditioning prepulses ranging from −100 mV to +40 mV were applied in +10 mV increments for 150 ms followed by a step to +40 mV for 500 ms. For current-clamp recording, the intracellular solution contained (in mM) 140 KMeSO4, 2 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 3 Na2ATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, pH 7.4. The bath solution for cultures was HBSS. Action potentials (APs) were generated by current injection from a holding potential of −70 mV. Throughout the recording, the holding potential was maintained by current injection. Intrinsic excitability was measured every 15 s using a constant amplitude small depolarizing pulse (800 ms, 10–80 pA). The amplitude that evoked 2–8 APs during the baseline period was selected and remained constant throughout the recording. The first spike latency was measured as the time between the stimulus onset and the first spike. The spike frequency was measured by counting the number of spikes within a depolarizing pulse of 800 ms.

Immunofluorescence.

FVB wild-type mice were anesthetized ip with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg) and perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde phosphate buffer (PB) solution. Lumbar spinal cords were dissected out and postfixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C, followed by cryoprotection in 30% sucrose/PB at 4°C. Coronal sections (30 μm) were cut with a cryostat (Leica, Nussloch, Germany) and were washed several times in 0.1 M PBS. All incubations and washes were performed at room temperature unless otherwise noted. Sections were then blocked in 3% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and 0.3% Triton X-100 in 0.1 M PBS (3% NGST) for 1 h. All primary antibodies were diluted in 3% NGST. Sections were incubated in a mixture of mouse anti-Kv4.2 (1:100; Antibodies Incorporated, Davis, CA) and rabbit polyclonal antivesicular glutamate transporter 2 (VGT2; 1:1,000; a generous gift from Dr. Robert H. Edwards, University of California, San Francisco, CA) or rabbit polyclonal anti-PKCγ (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 4°C overnight. Sections were rinsed with 3% NGST three times for 10 min each and were blocked in 10% NGST for 1 h, followed by incubation in a mixture of secondary goat anti-rabbit cyanine 5 (Cy5)-conjugated antibody (1:1,000; Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA) and goat anti-mouse Cy3-conjugated antibody (1:1,000; Zymed Laboratories) in 10% NGST. The sections were rinsed in PBS and observed under a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan).

Cultured spinal cord neurons were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 5 min and further fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 4°C. Cells were rinsed with 0.1 M PBS four times for 5 min each and then blocked in NGST for 1 h. All primary antibodies were diluted in 3% NGST. Cells were incubated in rabbit polyclonal anti-mGlu5 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) 1:1,600 or mouse anti-Kv4.2 (Antibodies Incorporated) 1:100 at 4°C overnight. Cells were rinsed with 3% NGST three times for 5 min each and were blocked in 10% NGST for 1 h, followed by incubation in secondary goat anti-rabbit Cy5-conjugated antibody (Zymed Laboratories) 1:1,000 or goat anti-mouse Cy3-conjugated antibody (Zymed Laboratories) 1:1,000 in 10% NGST. Cells were then rinsed in PBS and observed under a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus Optical). For double-staining of mGlu5 and neuronal nuclei (NeuN), Kv4.2 and NeuN, or VGT1, or VGT2, or neurokinin 1 (NK1), or PKCγ, the same procedure described above was used except for the antibodies. Briefly, cells were incubated in a mixture of mouse anti-Kv4.2 (Antibodies Incorporated) 1:200 and rabbit polyclonal VGT1 (a generous gift from Dr. Robert H. Edwards) 1:1,000 or VGT2 1:1,000 or NK1 (Chemicon, El Segundo, CA) 1:1,000 or PKCγ 1:1,000 primary. After washing, the cells were incubated in a mixture of secondary anti-rabbit Alexa-488-conjugated IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) 1:2,000 and anti-mouse Cy3-conjugated antibody 1:1,000 at room temperature.

Drug application.

(R,S)-3,5-Dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ballwin, MO) and dissolved in HBSS for bath application. DHPG (100 μM) was applied for 3 min.

Data analysis.

Offline evaluation was done using Pulse v8.62 software or PatchMaster (HEKA Elektronik) and Origin 7.1 or 8.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Data are expressed as original traces or as mean ± SE. The voltage dependence of activation and inactivation of IA was fitted with the Boltzmann function. For activation, peak currents were converted to conductance (G) by the formula G = I/(Vm − Vrev), where I is the current, Vm is the membrane voltage of depolarization pulses, and Vrev is the calculated potassium reversal potential (−84 mV). The function G/Gmax = 1/(1 + exp[(V1/2 − V)/k]) was used to normalize conductance, where Gmax is the maximal conductance obtained with a depolarizing pulse to +70 mV, V1/2 is the half-maximal voltage (V), and k is the slope factor. For inactivation, I/Imax = 1/(1 + exp[(V1/2 − V)/k]) was used, where Imax is the maximal current obtained with a −100 mV prepulse. The decay phase of A-type currents was fitted with a double-exponential equation [y = A1·exp(−x/t1) + A2·exp(−x/t2) + y0], where t1 and t2 were the decay time constants, and A1 and A2 were the proportions of each phase, respectively.

For all experiments, treatment effects were statistically analyzed by paired or two-sample Student's t-test. The distribution of firing patterns was statistically analyzed with a χ2 test. Error probabilities of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Expression of Kv4.2 in GAD67-GFP neurons.

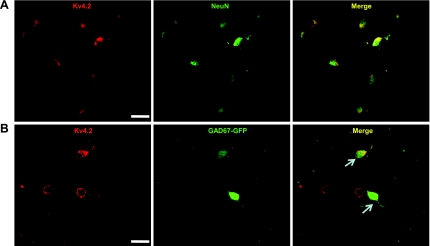

In previous studies, we found that a small portion of dorsal horn neurons does not have Kv4.2-mediated A-type currents (data not shown). To determine the percentage of Kv4.2-expressing neurons in dorsal horn cultures, we used NeuN as a neuronal marker and performed double-immunofluorescence staining for Kv4.2 and NeuN. Kv4.2 was exclusively expressed in neurons. Three hundred thirty-six out of 396 (85%) neurons were Kv4.2 positive (Fig. 1). Next we asked what subtype of neurons expresses Kv4.2. We took advantage of a transgenic mouse expressing GFP driven by the GAD67 promoter [GAD67-GFP or GIN mice (Oliva et al. 2000)] to examine Kv4.2 expression in GAD67-GFP neurons, which represent >67% of GABAergic inhibitory neurons (Dougherty et al. 2005, 2009). In the present study, 64 GAD67-GFP-expressing neurons were examined (note that only cells in the field where we saw GFP neurons were counted); 44 of these GAD67-GFP neurons also expressed Kv4.2. Thus 69% of GAD67-GFP neurons were Kv4.2 positive (Fig. 1). We also randomly counted 125 Kv4.2-positive cells, and only four of these neurons were GAD67-GFP positive. These results suggest that a very small proportion (3.2%) of Kv4.2-expressing neurons is GAD67-GFP positive, but among the GAD67-GFP neurons, most are Kv4.2 positive.

Fig. 1.

Colocalization of Kv4.2 with neuronal nuclei (NeuN) and expression of Kv4.2 in green fluorescent protein under the control of the glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 promoter (GAD67-GFP)-expressing dorsal horn neurons. A: representative confocal images of Kv4.2 (red) and NeuN (green) immunofluorescent staining in cultured dorsal horn neurons. The overlap of Kv4.2 and NeuN immunofluorescence is shown in yellow in the right panel titled “Merge”. B: representative confocal images of Kv4.2 (red) in GAD67-GFP-expressing dorsal horn neurons (green). The overlap of Kv4.2 immunofluorescence and GFP fluorescence is indicated with arrows in the right panel. Original scale bars: 40 μm.

Characterization of A-type currents in spinal dorsal horn GFP-expressing neurons.

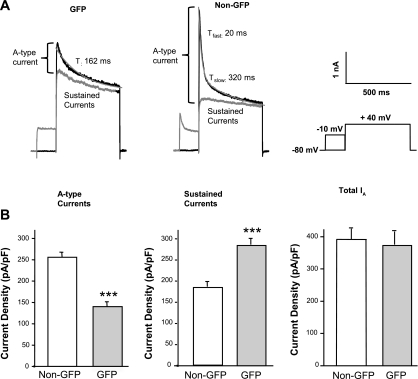

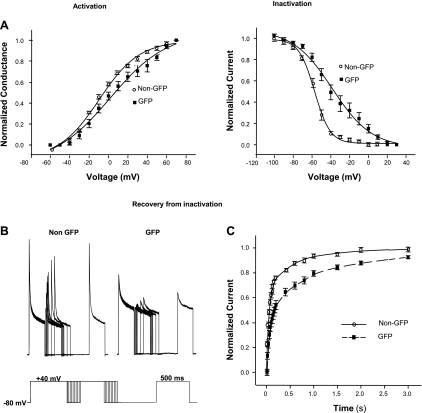

Following the observation described above, we asked whether Kv4.2 is functionally expressed in GAD67-GFP neurons. To answer this question, we performed voltage-clamp recordings in cultured spinal dorsal horn neurons expressing GFP and non-GFP neurons from GIN (GAD67-GFP) mouse pups. We found that the membrane capacitance and resting membrane potential were similar in both groups (data not shown). A-type currents from GIN transgenic mice were similar to those from wild-type FVB mice. Interestingly, A-type currents were much smaller (43.2%), whereas sustained currents were significantly larger (33.5%) in GFP-expressing neurons relative to the non-GFP neurons (Fig. 2). There was no difference in total outward IA between these two groups (Fig. 2B). Some GFP neurons (six out of 71) had no or very small A-type currents (≤200 pA). Most GFP neurons (53 out of 71; 75%) exhibited slowly decaying A-type currents best fit with a single time constant (190 ± 27 ms; n = 16) at a depolarizing step of +40 mV (Fig. 2A) and slower recovery from steady-state inactivation with only <75% recovery from inactivation after 800 ms (Fig. 3B). Non-GFP neurons (37 out of 42; 88%) from the same cultures expressed A-type currents with fast activation and rapid inactivation best fit with two time constants (τfast of 20 ± 1 ms and τslow of 298 ± 24 ms; n = 13; Fig. 2A) and >90% recovery from inactivation after 800 ms (Fig. 3B). Activation curves of A-type currents from GAD67-GFP neurons were significantly right-shifted from −7.0 ± 1.5 mV (n = 10) to +1.8 ± 2.1 mV (n = 13; P < 0.05), but the slope of the activation curve was not markedly different (Fig. 3A). In addition, steady-state inactivation curves in GAD67-GFP neurons were significantly shifted from −56.0 ± 1.0 mV (n = 15) to −35.6 ± 4.1 mV (n = 25; P < 0.05); the slope of the inactivation curve in these neurons was also altered from 8.5 ± 0.4 (n = 15) to 16.0 ± 2.3 (n = 25; P < 0.05; Fig. 3A). All of these differences in the properties of A-type currents in GAD67-GFP neurons relative to non-GFP neurons indicate that the majority of these GABAergic neurons expresses little or no Kv4.2-mediated A-type currents, whereas Kv4.2-like A-type currents are much more robustly expressed in the non-GFP population of dorsal horn neurons.

Fig. 2.

Outward potassium currents (IA) recorded from dorsal horn neurons isolated from GAD67-GFP mice. A: representative IA recorded from GAD67-GFP-expressing neurons and non-GFP neurons in the same cultures prepared from spinal cords of GIN mice (black trace: nonconditioned current; gray trace: conditioned current). Right panel: protocol for isolation of A-type currents. B: mean densities of A-type currents, sustained currents, and total IA in non-GFP (n = 41) and GAD56-GFP-expressing neurons (n = 71). Tfast/slow, fast and slow decay time constants. Values represent mean ± SE; ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 3.

The kinetic profile of A-type currents in GAD67-GFP-expressing dorsal horn neurons and non-GFP neurons from GIN mice. A: steady-state activation and inactivation curves from non-GFP neurons (n = 13) or GAD67-GFP-expressing neurons (n = 15). B: recovery from inactivation of A-type currents in non-GFP (n = 15) or GAD67-GFP-expressing (n = 25) neurons. C: representative recordings from non-GFP and GAD67-GFP-expressing neurons showing recovery from inactivation of A-type currents in these cells. Inset: protocol for recovery from inactivation, where first duration of voltage step from 40 to −80 mV is 3 ms; incremental duration, 20 ms.

Intrinsic membrane properties in GAD67-GFP neurons.

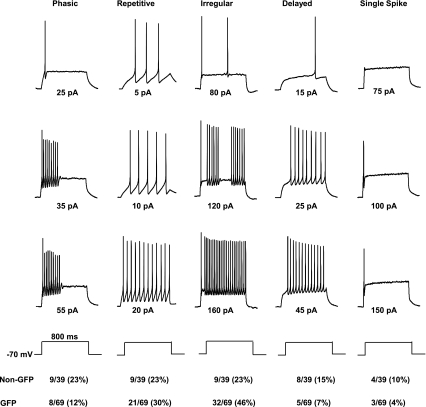

We and others (Heinke et al. 2004; Hu and Gereau 2003; Ruscheweyh and Sandkuhler 2002) have previously identified at least four categories of dorsal horn neurons based on firing patterns. In the present study, a total of 108 cultured dorsal horn neurons from GIN mice was examined. AP firing patterns from GIN transgenic mice were similar to those from wild-type FVB mice. The mean rheobase in GAD67-GFP neurons (47.0 ± 3.5 pA; n = 42) was not significantly different from that in non-GFP neurons (42.4 ± 6.2 pA; n = 27; P > 0.05). The neurons could be divided into five categories, according to their firing patterns when depolarized from a holding potential of −70 mV (Fig. 4): 1) phasic firing (the spike amplitude was markedly attenuated at the end of strong depolarizing steps); 2) repetitive firing (no spike amplitude attenuation at higher current injection); 3) irregular firing pattern [including gap firing; we previously combined this group with the repetitive firing group (Hu and Gereau 2003)]; 4) delayed firing (a delay between the onset of current injection and the first AP); and 5) single spike (even at strong depolarization). Similar to our previous study (Hu and Gereau 2003), non-GFP neurons showed an approximately equal distribution of phasic, repetitive, delayed, and irregular firing pattern (21–23%). When only considering GAD67-GFP neurons, the distribution of firing patterns was significantly different (P < 0.05; χ2 test) with a decrease in the proportion of phasic and delayed firing patterns and an increase in the proportion of repetitive and irregular firing patterns (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Firing patterns in response to depolarizing current injection in cultured dorsal horn neurons from GIN mice. Firing properties of the neurons can be divided into 5 groups: phasic (cells showing spike-frequency adaptation), repetitive, irregular, delayed firing, and single spike. Current injection protocols are shown below voltage traces. All neurons are manually clamped at −70 mV by current injection.

Activation of mGlu5 does not modulate A-type currents or neuronal excitability in GAD67-GFP-expressing neurons.

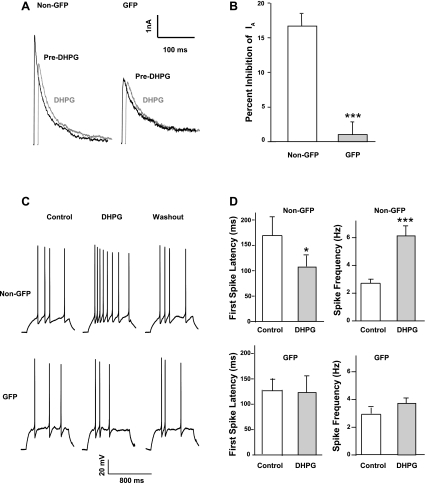

We have shown previously that activation of mGlu5 by DHPG inhibits Kv4.2-mediated A-type currents and increases neuronal excitability in spinal dorsal horn neurons (Hu et al. 2007). As demonstrated above, the GAD67-GFP-expressing neurons express very little Kv4.2-mediated A-type current. We sought to test whether DHPG modulates A-type currents and neuronal excitability in this subgroup, GABAergic neurons. We performed both voltage-clamp and current-clamp recordings and evaluated the DHPG effect on A-type currents and neuronal excitability in GAD67-GFP-expressing and non-GFP neurons. In voltage-clamp recordings, bath application of 100 μM DHPG for 3 min had no effect on A-type currents in GAD67-GFP neurons, whereas DHPG decreased A-type currents in non-GFP neurons, as we reported previously (Fig. 5, A and B). In current-clamp recordings, we recorded APs from neurons with different firing patterns (except single spike). DHPG decreased first spike latency and increased spike frequency in non-GFP neurons but had no significant effect on firing properties of GAD67-GFP neurons (Fig. 5, C and D). These results demonstrate that mGlu5-Kv4.2 signaling is not associated with this type of GABAergic neurons.

Fig. 5.

(R,S)-3,5-Dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG)-induced modulation of A-type currents and neuronal excitability is absent in GAD67-GFP-expressing neurons. A: representative traces of A-type currents recorded before (Pre-DHPG) and 3 min after application of 100 μM DHPG to non-GFP or GAD67-GFP-expressing neurons in the same preparations. B: summary of the effects of DHPG on peak amplitude of A-type currents in non-GFP (n = 7) or GAD67-GFP-expressing neurons (n = 9). Values represent mean ± SE; ***P < 0.001; 2-sample Student's t-test. C: representative APs recorded in non-GFP or GAD67-GFP-expressing neurons in cultures from GIN mice before and 3 min after application of 100 μM DHPG. D: summary of changes in first spike latency and spike frequency induced by DHPG in non-GFP (n = 7) or GAD67-GFP neurons (n = 9) from GIN mice. Values represent mean ± SE; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; paired Student's t-test.

Expression of mGlu5 in GAD67-GFP neurons.

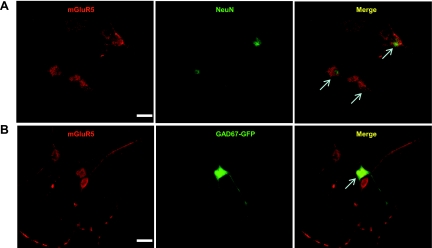

As we showed above, DHPG did not modulate A-type currents or neuronal excitability in GAD67-GFP neurons. We next asked whether mGlu5 protein is expressed in GAD67-GFP neurons. We performed immunofluorescence staining for mGlu5 in dorsal horn neurons cultured from GIN pups. Consistent with previous studies in other labs (Edling et al. 2007; Janssens and Lesage 2001), mGlu5 was not only expressed in neurons but also expressed in glial cells in the dorsal horn. A total of 280 NeuN-positive cells (neurons) and 242 mGlu5-positive cells was examined. One hundred ninety-two cells coexpressed NeuN and mGlu5. Thus 68.6% of neurons expressed mGlu5, and 78.3% mGlu5-positive cells were neurons (Fig. 6). We next examined the coexpression of mGlu5 and GAD67-GFP: a total of 222 mGlu5-positive cells was examined; 36 of these neurons expressed both mGlu5 and GAD67-GFP. Thus 16% of mGlu5 cells also expressed GAD67-GFP (Fig. 6). We also randomly counted 140 mGlu5-positive cells and found that only 10 of 140 (7%) of these cells expressed GAD67-GFP. These results suggest that mGlu5 protein is only minimally expressed in the GAD67-GFP-expressing population of inhibitory neurons.

Fig. 6.

Colocalization of metabotropic glutamate 5 receptor (mGluR5) with NeuN and expression of mGluR5 in GAD67-GFP-expressing dorsal horn neurons. A: representative confocal images of mGluR5 (red) and NeuN (green) immunofluorescent staining in cultured dorsal horn neurons. B: representative confocal images of mGluR5 (red) in GAD67-GFP-expressing dorsal horn neurons (green). The colocalization of mGluR5 and NeuN or GFP is indicated with arrows in the right panel, titled Merge. Original scale bars: 40 μm.

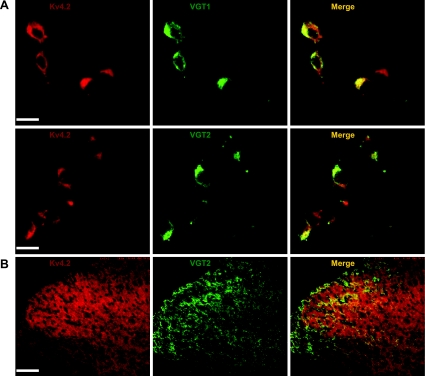

Coexpression of Kv4.2 and vesicular glutamate transporters.

Since only 3.2% of Kv4.2-positive neurons express GAD67-GFP, we hypothesized that the majority of Kv4.2-positive neurons includes excitatory neurons. It has been shown that VGT1 or VGT2 is selectively expressed in glutamatergic neurons (Bellocchio et al. 1998; Brumovsky et al. 2007; Fujiyama et al. 2001; Ponzio et al. 2006; Todd et al. 2003). We performed double-immunofluorescence staining for Kv4.2 and VGT1 or VGT2. Both VGT1 and VGT2 were detected in most cultured dorsal horn neurons. Sixty-eight out of 73 (93%) Kv4.2-positive neurons were VGT1 positive; 67 out of 70 (96%) VGT1 neurons were Kv4.2 positive (Fig. 7A). Seventy-seven out of 88 (88%) Kv4.2-positive neurons were VGT2 positive; 76 out of 80 (95%) VGT2 neurons were Kv4.2 positive (Fig. 7A). Thus both VGT1 and VGT2 proteins are highly colocalized with Kv4.2. To further confirm Kv4.2 colocalization with VGT2, we double-labeled spinal cord sections from adult mice with antibodies against Kv4.2 and VGT2. Confocal images showed that there was a significant overlap between the distributions of Kv4.2 and VGT2 in the superficial dorsal horn (Fig. 7B). These results suggest that the majority of Kv4.2-expressing neurons includes glutamatergic neurons in the spinal dorsal horn.

Fig. 7.

Colocalization of Kv4.2 and vesicular glutamate transporters (VGTs) in dorsal horn neurons. A: representative confocal images of Kv4.2 (red) and VGT1 or VGT2 (green) coimmunofluorescence in cultured dorsal horn neurons. B: representative confocal images of Kv4.2 (red) and VGT2 (green) coimmunofluorescence in the mouse dorsal horn. Merge of Kv4.2 and VGTs is shown in yellow. Original scale bars: A, 40 μm; B, 200 μm.

Coexpression of Kv4.2 and NK1 or PKCγ.

It has been demonstrated that NK1 and PKCγ are markers of excitatory neurons in the spinal cord dorsal horn (Littlewood et al. 1995; Polgar et al. 1999) and modulators of nociception. We sought to examine Kv4.2 colocalzation with these two proteins to further determine the neurochemical phenotype of Kv4.2-expressing neurons. We performed double-immunofluorescence staining for Kv4.2 and NK1 or PKCγ. Both NK1 and PKCγ were widely expressed in cultured dorsal horn neurons. One hundred eleven out of 140 (86%) Kv4.2-positive neurons were NK1 positive; 111 of 132 (84%) NK1 cells were Kv4.2 positive (Fig. 8A). Seventy of 82 (85%) Kv4.2-positive neurons were PKCγ positive, and 100% of 70 PKCγ-positive neurons were Kv4.2 positive (Fig. 8B). Both NK1 and PKCγ proteins were highly colocalized with Kv4.2. Consistent with this finding, immunofluorescence staining of adult mouse spinal cord slices revealed that Kv4.2 was overlapped with NK1 and PKCγ in the dorsal horn (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Colocalization of Kv4.2 and neurokinin 1 (NK1) or PKCγ. A: representative confocal images of Kv4.2 (red) and NK1 (green) immunofluorescence in dorsal horn neurons and in the mouse dorsal horn. B: representative confocal images of Kv4.2 (red) and PKCγ (green) immunofluorescence in dorsal horn neurons and in the mouse dorsal horn. Merge of Kv4.2 with NK1 or PKCγ is shown in yellow. Original scale bars: cultured cells, 40 μm; slices, 200 μm.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrate that the majority of Kv4.2-expressing neurons includes excitatory neurons. This result is consistent with the recent finding showing that A-type currents are associated with excitatory dorsal horn lamina II neurons (Yasaka et al. 2010). Our immunocytochemistry data showed that a very limited number of Kv4.2-expressing neurons are GAD67-GFP positive, whereas the majority of Kv4.2-expressing neurons expresses VGT1/2, which are markers of excitatory neurons. This suggests that the majority of Kv4.2-expressing neurons is glutamatergic. However, a significant proportion of GAD67-GFP neurons is Kv4.2 positive, indicating that Kv4.2 is also expressed in some inhibitory neurons. Interestingly, electrophysiological data reveal that Kv4.2-mediated A-type currents are not functionally expressed in the majority of GAD67-GFP neurons, which show either no A-type currents or A-type currents with slower kinetics, suggesting minimal contribution of Kv4.2. This discrepancy may be the result of an insufficient trafficking of Kv4.2 protein to the membrane of these neurons. Another possibility is that Kv4.2 is expressed in the cell surface membrane with very low density and thus contributes only very minimally to whole-cell K+ currents. Immunostaining provides information regarding protein expression, which does not necessarily correlate with channel functional expression (Li et al. 2011; Schultz et al. 2007).

We have reported that genetic deletion of Kv4.2 decreases rheobase and increases excitability of dorsal horn neurons (Hu et al. 2006). In this study, we did not observe any differences in rheobase in GAD67-GFP neurons relative to non-GFP neurons, although A-type currents are relatively smaller in the GAD67-GFP neurons. Since the delayed rectifier currents (sustained currents) are significantly larger in the GAD67-GFP neurons relative to non-GFP neurons, total IA was similar in GAD67-GFP neurons compared with non-GFP neurons, suggesting that total IA (not just A-type currents) likely contributes to setting the rheobase. We also characterized the firing patterns of GAD67-GFP neurons and find that these neurons have decreased prevalence of phasic and delayed firing patterns and an increase in the prevalence of repetitive and irregular firing patterns relative to non-GFP neurons in the same culture preparations. These differences that we observed in the firing properties of GAD67-GFP neurons relative to non-GFP neurons are similar to what we observed in dorsal horn neurons from Kv4.2 knockout mice relative to wild-type controls (Hu et al. 2006). While we propose that the essential lack of Kv4.2-mediated A-type currents in GAD67-GFP neurons, relative to non-GFP neurons, contributes to these differences in AP firing patterns, there are, of course, many other possible mechanisms by which firing properties can be altered.

Our electrophysiological results demonstrate that the steady-state activation and inactivation curves are rightward shifted in the GFP population, suggesting that the genes encoding A-type currents in GFP neurons may be different from those in non-GFP neurons. A-type currents can be mediated by several genes, such as Kv1.4, Kv3.4, Kv4.1, Kv4.2, and Kv4.3. GFP neurons lack Kv4.2-like currents but have slowly decaying A-type currents. A previous study from Tsaur's lab (Huang et al. 2005) revealed that Kv4.3 is expressed in a subset of excitatory interneurons. Ours and Huang's (Huang et al. 2005) studies suggested that GFP neurons may not express Kv4.2 and Kv4.3. The molecular identity of A-type channels in these dorsal horn neurons remains to be determined.

It is well established that mGlu5 plays important roles in nociceptive plasticity (Fisher and Coderre 1996; Karim et al. 2001). Numerous behavioral studies have demonstrated that mGlu5 in the dorsal horn contributes to inflammatory, visceral, and neuropathic pain (Chen et al. 2000; Fisher et al. 2002; Karim et al. 2001; Montana et al. 2009; Young et al. 1997). We have demonstrated that activation of mGlu5 induces ERK activation, which subsequently inhibits Kv4.2-mediated A-type currents and increases excitability in spinal cord dorsal horn neurons. In the present study, we demonstrate that mGlu5 does not modulate A-type currents or neuronal excitability in GAD67-GFP neurons, whereas in the “non-GFP” population of dorsal horn neurons, this modulation is robust, similar to our previous reports (Hu et al. 2007). This suggests that the mGlu5-Kv4.2 signaling pathway is not operational in this GAD67-GFP population of inhibitory neurons in the dorsal horn. Although immunostaining reveals that one-third of GAD67-GFP neurons expresses mGlu5, it is not surprising that we did not observe the mGlu5-mediated modulation of A-type currents in GAD67-GFP neurons, as the majority of these neurons do not functionally express Kv4.2-mediated A-type currents. The A-type currents observed in 17% of GAD67-GFP neurons may be mediated by other potassium channels, which are not modulated by a mGlu5-activated signal pathway.

We further refined the subpopulations of Kv4.2-expressing neurons by immunocytochemical staining undertaken to examine Kv4.2 coexpression with NK1 and PKCγ. It has been proposed that NK1-positive neurons are glutamatergic projection neurons or interneurons in the superficial dorsal horn (Blomeley et al. 2009; Cordero-Erausquin et al. 2004; Jakab et al. 1996; Littlewood et al. 1995). Our results show that Kv4.2 is highly colocalized with NK1, indicating that Kv4.2 modulation in these NK1-expressing neurons could contribute to central sensitization. Indeed, previous reports have suggested that NK1 receptor-expressing neurons are critical for the development of injury-induced hypersensitivity and are required for the development of central sensitization (Khasabov et al. 2002; Mantyh et al. 1997; Nichols et al. 1999). A recent report has shown that the NK1 receptor is only expressed in ∼34% lamina I–III neurons (NeuN-positive) from the adult rat spinal cord (Khan et al. 2008). However, in our dorsal horn cultures, the percentage of neurons expressing NK1 is much higher than 34%, since 85% of these neurons are Kv4.2 positive, and 86% of Kv4.2-positive neurons are NK1 positive. The difference could be due to a species, developmental-stage issue or altered protein expression associated with culturing.

PKCγ has also been strongly implicated in the development of injury-induced, persistent pain conditions, particularly in the development of tactile allodynia (Braz and Basbaum 2009). PKCγ neurons have been shown to be located in lamina IIi (Malmberg et al. 1997). Our result from cultured dorsal horn neurons showed that 85% of Kv4.2-expressing neurons are PKCγ positive, whereas 100% of PKCγ neurons are immunoreactive for Kv4.2. Confocal imaging showed that PKCγ immunoreactivity overlaps with Kv4.2 immunoreactivity in the spinal cord dorsal horn. We have previously shown that activation of PKC by PMA reduces Kv4.2-mediated A-type currents and neuronal excitability in dorsal horn neurons via activation of ERK (Hu and Gereau 2003). The findings presented here are consistent with the hypothesis that PMA-induced inhibition of A-type currents in some dorsal horn neurons is likely mediated by activation of PKCγ.

It should be noted that our staining results revealed that NK-1 and PKCγ appear to be highly coexpressed in the cultured dorsal horn neurons. Previous reports from Todd's lab (Polgar et al. 1999) showed that only 22% and 36.7% of the NK1 receptor-immunoreactive neurons are PKCγ immunoreactive in lamina I and III, respectively, from the adult rat spinal cord. However, the difference could be due to a species, developmental-stage issue or altered protein expression associated with culturing.

The electrophysiological results demonstrate that Kv4.2 is expressed in the soma, as we recorded somatic Kv4.2-mediated currents from cultured neurons without or with short processes, which is consistent with Kv4.2 somatic staining. Our confocal imaging data showed that VGT1/2 labeled both the soma and processes and highly colocalized with Kv4.2 in our culture conditions. However, previous reports suggest that VGT1/2 staining is restricted to dorsal horn synaptic terminals in fixed spinal cord sections, with little or no labeling associated with neuronal somata (Landry et al. 2004; Li et al. 2003; Todd et al. 2003). The relatively greater abundance of VGT1/2 labeling in the soma of cultured neurons may reflect altered protein expression or trafficking associated with the isolation of the cells, or this could be related to differences in the age of the animals used in preparing cultures vs. slices.

Previous studies have shown that GAD67-expressing neurons represent more than two-thirds of GABAergic inhibitory neurons in the superficial dorsal horn (Dougherty et al. 2005, 2009). Our present results reveal that these neurons express little or no Kv4.2-mediated A-type currents and that the Kv4.2 subunit is mainly expressed in excitatory neurons, indicating that inhibition of Kv4.2 activity likely increases excitation of predominantly excitatory neurons in the spinal dorsal horn circuit. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that mGlu5 modulation of Kv4.2-containing K+ channels occurs only in excitatory neurons in the spinal cord dorsal horn, suggesting that the pronociceptive actions of mGlu5/ERK signaling, which is mediated largely by downstream inhibition of Kv4.2 (Hu et al. 2006, 2007), are mediated by modulation of excitatory dorsal horn neurons.

It is important to point out that the lack of GFP expression does not indicate that neurons are not GABAergic. By focusing on the GAD67-GFP neurons, we may be restricting our analysis to only a subset of GABAergic neurons, and thus our findings cannot be attributed to all GABAergic neurons in the dorsal horn. The relative abundance of A-type currents and firing patterns in this GFP-positive population of interneurons is therefore only a subset of GABAergic interneurons, and the abundance of these properties and of mGlu5-dependent modulation of these properties may differ in other GABAergic interneurons. It should also be noted that a recent paper from Andrew Todd's group (Yasaka et al. 2010) indicates that there is a similar association of firing patterns indicative of A-type currents with excitatory neurons in lamina II from the adult rat. This study used immunohistochemical identification of GABAergic interneurons and did not rely on GFP expression from the GAD67 locus. Therefore, these findings in another species using different methods lend support to our overall interpretation.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS48602) to R. W. Gereau IV.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Robert H. Edwards for providing the rabbit polyclonal antivesicular glutamate transporters 1 and 2.

REFERENCES

- Baba et al., 2003. Baba H, Ji RR, Kohno T, Moore KA, Ataka T, Wakai A, Okamoto M, Woolf CJ. Removal of GABAergic inhibition facilitates polysynaptic A fiber-mediated excitatory transmission to the superficial spinal dorsal horn. Mol Cell Neurosci 24: 818–830, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba et al., 1998. Baba H, Kohno T, Okamoto M, Goldstein PA, Shimoji K, Yoshimura M. Muscarinic facilitation of GABA release in substantia gelatinosa of the rat spinal dorsal horn. J Physiol 508: 83–93, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellocchio et al., 1998. Bellocchio EE, Hu H, Pohorille A, Chan J, Pickel VM, Edwards RH. The localization of the brain-specific inorganic phosphate transporter suggests a specific presynaptic role in glutamatergic transmission. J Neurosci 18: 8648–8659, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomeley et al., 2009. Blomeley CP, Kehoe LA, Bracci E. Substance P mediates excitatory interactions between striatal projection neurons. J Neurosci 29: 4953–4963, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braz and Basbaum, 2009. Braz JM, Basbaum AI. Triggering genetically-expressed transneuronal tracers by peripheral axotomy reveals convergent and segregated sensory neuron-spinal cord connectivity. Neuroscience 163: 1220–1232, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumovsky et al., 2007. Brumovsky P, Watanabe M, Hokfelt T. Expression of the vesicular glutamate transporters-1 and -2 in adult mouse dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord and their regulation by nerve injury. Neuroscience 147: 469–490, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen et al., 2000. Chen Y, Bacon G, Sher E, Clark BP, Kallman MJ, Wright RA, Johnson BG, Schoepp DD, Kingston AE. Evaluation of the activity of a novel metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist (+/−)-2-amino-2-(3-cis and trans-carboxycyclobutyl-3-(9-thioxanthyl)propionic acid) in the in vitro neonatal spinal cord and in an in vivo pain model. Neuroscience 95: 787–793, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Erausquin et al., 2004. Cordero-Erausquin M, Pons S, Faure P, Changeux JP. Nicotine differentially activates inhibitory and excitatory neurons in the dorsal spinal cord. Pain 109: 308–318, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty et al., 2005. Dougherty KJ, Sawchuk MA, Hochman S. Properties of mouse spinal lamina I GABAergic interneurons. J Neurophysiol 94: 3221–3227, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty et al., 2009. Dougherty KJ, Sawchuk MA, Hochman S. Phenotypic diversity and expression of GABAergic inhibitory interneurons during postnatal development in lumbar spinal cord of glutamic acid decarboxylase 67-green fluorescent protein mice. Neuroscience 163: 909–919, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edling et al., 2007. Edling Y, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Simi A. Glutamate activates c-fos in glial cells via a novel mechanism involving the glutamate receptor subtype mGlu5 and the transcriptional repressor DREAM. Glia 55: 328–340, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher and Coderre, 1996. Fisher K, Coderre TJ. The contribution of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) to formalin-induced nociception. Pain 68: 255–263, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher et al., 2002. Fisher K, Lefebvre C, Coderre TJ. Antinociceptive effects following intrathecal pretreatment with selective metabotropic glutamate receptor compounds in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 73: 411–418, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiyama et al., 2001. Fujiyama F, Furuta T, Kaneko T. Immunocytochemical localization of candidates for vesicular glutamate transporters in the rat cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol 435: 379–387, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinke et al., 2004. Heinke B, Ruscheweyh R, Forsthuber L, Wunderbaldinger G, Sandkuhler J. Physiological, neurochemical and morphological properties of a subgroup of GABAergic spinal lamina II neurones identified by expression of green fluorescent protein in mice. J Physiol 560: 249–266, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu et al., 2007. Hu HJ, Alter BJ, Carrasquillo Y, Qiu CS, Gereau RW. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 modulates nociceptive plasticity via extracellular signal-regulated kinase-Kv4.2 signaling in spinal cord dorsal horn neurons. J Neurosci 27: 13181–13191, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu et al., 2006. Hu HJ, Carrasquillo Y, Karim F, Jung WE, Nerbonne JM, Schwarz TL, Gereau RW., 4th The kv4.2 potassium channel subunit is required for pain plasticity. Neuron 50: 89–100, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu and Gereau, 2003. Hu HJ, Gereau RW. ERK integrates PKA and PKC signaling in superficial dorsal horn neurons. II. Modulation of neuronal excitability. J Neurophysiol 90: 1680–1688, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu et al., 2003. Hu HJ, Glauner KS, Gereau RW. ERK integrates PKA and PKC signaling in superficial dorsal horn neurons. I. Modulation of A-type K+ currents. J Neurophysiol 90: 1671–1679, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang et al., 2005. Huang HY, Cheng JK, Shih YH, Chen PH, Wang CL, Tsaur ML. Expression of A-type K channel alpha subunits Kv 4.2 and Kv 43 in rat spinal lamina II excitatory interneurons and colocalization with pain-modulating molecules. Eur J Neurosci 22: 1149–1157, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakab et al., 1996. Jakab RL, Hazrati LN, Goldman-Rakic P. Distribution and neurochemical character of substance P receptor (SPR)-immunoreactive striatal neurons of the macaque monkey: accumulation of SP fibers and SPR neurons and dendrites in “striocapsules” encircling striosomes. J Comp Neurol 369: 137–149, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens and Lesage, 2001. Janssens N, Lesage AS. Glutamate receptor subunit expression in primary neuronal and secondary glial cultures. J Neurochem 77: 1457–1474, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim et al., 2001. Karim F, Wang CC, Gereau RW. Metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes 1 and 5 are activators of extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling required for inflammatory pain in mice. J Neurosci 21: 3771–3779, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan et al., 2008. Khan IM, Wart CV, Singletary EA, Stanislaus S, Deerinck T, Yaksh TL, Printz MP. Elimination of rat spinal substance P receptor bearing neurons dissociates cardiovascular and nocifensive responses to nicotinic agonists. Neuropharmacology 54: 269–279, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasabov et al., 2002. Khasabov SG, Rogers SD, Ghilardi JR, Peters CM, Mantyh PW, Simone DA. Spinal neurons that possess the substance P receptor are required for the development of central sensitization. J Neurosci 22: 9086–9098, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuner, 2010. Kuner R. Central mechanisms of pathological pain. Nat Med 16: 1258–1266, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry et al., 2004. Landry M, Bouali-Benazzouz R, El Mestikawy S, Ravassard P, Nagy F. Expression of vesicular glutamate transporters in rat lumbar spinal cord, with a note on dorsal root ganglia. J Comp Neurol 468: 380–394, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al., 2003. Li JL, Xiong KH, Dong YL, Fujiyama F, Kaneko T, Mizuno N. Vesicular glutamate transporters, VGluT1 and VGluT2, in the trigeminal ganglion neurons of the rat, with special reference to coexpression. J Comp Neurol 463: 212–220, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al., 2010. Li JQ, Chen SR, Chen H, Cai YQ, Pan HL. Regulation of increased glutamatergic input to spinal dorsal horn neurons by mGluR5 in diabetic neuropathic pain. J Neurochem 112: 162–172, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al., 2011. Li Y, Liu X, Wu Y, Xu Z, Li H, Griffith LC, Zhou Y. Intracellular regions of the Eag potassium channel play a critical role in generation of voltage-dependent currents. J Biol Chem 286: 1389–1399, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlewood et al., 1995. Littlewood NK, Todd AJ, Spike RC, Watt C, Shehab SA. The types of neuron in spinal dorsal horn which possess neurokinin-1 receptors. Neuroscience 66: 597–608, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg et al., 1997. Malmberg AB, Chen C, Tonegawa S, Basbaum AI. Preserved acute pain and reduced neuropathic pain in mice lacking PKCgamma. Science 278: 279–283, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantyh et al., 1997. Mantyh PW, Rogers SD, Honore P, Allen BJ, Ghilardi JR, Li J, Daughters RS, Lappi DA, Wiley RG, Simone DA. Inhibition of hyperalgesia by ablation of lamina I spinal neurons expressing the substance P receptor. Science 278: 275–279, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montana et al., 2009. Montana MC, Cavallone LF, Stubbert KK, Stefanescu AD, Kharasch ED, Gereau RW. The metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 antagonist fenobam is analgesic and has improved in vivo selectivity compared with the prototypical antagonist 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 330: 834–843, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols et al., 1999. Nichols ML, Allen BJ, Rogers SD, Ghilardi JR, Honore P, Luger NM, Finke MP, Li J, Lappi DA, Simone DA, Mantyh PW. Transmission of chronic nociception by spinal neurons expressing the substance P receptor. Science 286: 1558–1561, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva et al., 2000. Oliva AA, Jr, Jiang M, Lam T, Smith KL, Swann JW. Novel hippocampal interneuronal subtypes identified using transgenic mice that express green fluorescent protein in GABAergic interneurons. J Neurosci 20: 3354–3368, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson et al., 2006. Persson S, Boulland JL, Aspling M, Larsson M, Fremeau RT, Jr, Edwards RH, Storm-Mathisen J, Chaudhry FA, Broman J. Distribution of vesicular glutamate transporters 1 and 2 in the rat spinal cord, with a note on the spinocervical tract. J Comp Neurol 497: 683–701, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher et al., 2007. Pitcher MH, Ribeiro-da-Silva A, Coderre TJ. Effects of inflammation on the ultrastructural localization of spinal cord dorsal horn group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Comp Neurol 505: 412–423, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polgar et al., 1999. Polgar E, Fowler JH, McGill MM, Todd AJ. The types of neuron which contain protein kinase C gamma in rat spinal cord. Brain Res 833: 71–80, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponzio et al., 2006. Ponzio TA, Ni Y, Montana V, Parpura V, Hatton GI. Vesicular glutamate transporter expression in supraoptic neurones suggests a glutamatergic phenotype. J Neuroendocrinol 18: 253–265, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscheweyh and Sandkuhler, 2002. Ruscheweyh R, Sandkuhler J. Lamina-specific membrane and discharge properties of rat spinal dorsal horn neurones in vitro. J Physiol 541: 231–244, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz et al., 2007. Schultz JH, Volk T, Bassalay P, Hennings JC, Hubner CA, Ehmke H. Molecular and functional characterization of Kv4.2 and KChIP2 expressed in the porcine left ventricle. Pflügers Arch 454: 195–207, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takazawa and MacDermott, 2010. Takazawa T, MacDermott AB. Synaptic pathways and inhibitory gates in the spinal cord dorsal horn. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1198: 153–158, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd et al., 2003. Todd AJ, Hughes DI, Polgar E, Nagy GG, Mackie M, Ottersen OP, Maxwell DJ. The expression of vesicular glutamate transporters VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 in neurochemically defined axonal populations in the rat spinal cord with emphasis on the dorsal horn. Eur J Neurosci 17: 13–27, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torsney and MacDermott, 2006. Torsney C, MacDermott AB. Disinhibition opens the gate to pathological pain signaling in superficial neurokinin 1 receptor-expressing neurons in rat spinal cord. J Neurosci 26: 1833–1843, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasaka et al., 2010. Yasaka T, Tiong SY, Hughes DI, Riddell JS, Todd AJ. Populations of inhibitory and excitatory interneurons in lamina II of the adult rat spinal dorsal horn revealed by a combined electrophysiological and anatomical approach. Pain 151: 475–488, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young et al., 1997. Young MR, Fleetwood-Walker SM, Dickinson T, Blackburn-Munro G, Sparrow H, Birch PJ, Bountra C. Behavioural and electrophysiological evidence supporting a role for group I metabotropic glutamate receptors in the mediation of nociceptive inputs to the rat spinal cord. Brain Res 777: 161–169, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]