Abstract

Methamphetamine (METH) is a toxic drug of abuse, which can cause significant decreases in the levels of monoamines in various brain regions. However, animals treated with progressively increasing doses of METH over several weeks are protected against the toxic effects of the drug. In the present study, we tested the possibility that this pattern of METH injections might be associated with transcriptional changes in the rat striatum, an area of the brain which is known to be very sensitive to METH toxicity and which is protected by METH preconditioning. We found that the presence and absence of preconditioning followed by injection of large doses of METH caused differential expression in different sets of striatal genes. Quantitative PCR confirmed METH-induced changes in some genes of interest. These include small heat shock 27 kD proteins 1 and 2 (HspB1 and HspB2), brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and heme oxygenase-1 (Hmox-1). Our observations are consistent with previous studies which have reported that ischemic or pharmacological preconditioning can cause reprogramming of gene expression after lethal ischemic insults. These studies add to the growing literature on the effects of preconditioning on the brain transcriptome.

Keywords: methamphetamine, preconditioning, striatum, BDNF, heat shock proteins

INTRODUCTION

Methamphetamine (METH) is an illicit drug which has become an international public health problem. Specifically, METH abuse is associated with many negative consequences which include altered behavioral and cognitive functions (Murray 1998; Scott et al. 2007; Darke et al. 2008). Withdrawal from METH causes anhedonia and intense craving for the drug (Zweben et al. 2004; Sekine et al. 2006; Darke et al. 2008). The negative neuropsychiatric consequences of METH abuse are thought to be due to drug-induced neurodegenerative effects in METH addicts (Scott et al. 2007). Patterns of METH abuse are multiple but usually involve the intake of small doses of the drug followed by gradual increases to larger doses of the psychostimulant (Kramer et al. 1967). Neuropsychological tests have revealed that METH addicts who abuse these large doses suffer from cognitive deficits (Simon et al. 2002; Sekine et al. 2003) and structural abnormalities in their brains (Chang et al. 2007; Sekine et al. 2008). METH-dependent patients indeed suffer from decreases in dopamine (DA) (Volkow et al. 2001) and of serotonin (5-HT) transporters (Sekine et al. 2006).

Many of these neuropathological changes have been replicated in animal models (Krasnova and Cadet 2009). Specifically, METH can cause decreases in DA, 5-HT, and DA transporters (DAT) in various brain regions (Cadet et al. 1994; Deng et al. 1999; Ladenheim et al. 2000; Thomas and Kuhn 2005; Cadet et al. 2007). These experiments focused on the use of moderate to large doses of METH injected during single-day binges (Cadet et al. 2003). However, several groups have now experimented with administration of increasing METH doses over several days prior to challenging the animals with toxic doses of the drug and have found that these patterns of drug administration can provide protection against METH toxicity (Johnson-Davis et al. 2003; Danaceau et al. 2007; Graham et al. 2008; Cadet et al. 2009a). Cadet and colleagues (2009a) have recently suggested that this pattern of drug administration is comparable with other models of brain preconditioning (Calabrese 2008; Obrenovitch 2008) and might involve similar molecular mechanisms of protection (Cadet and Krasnova 2009). For example, it has been reported that brain preconditioning by various manipulations is associated with differential gene expression in the presence of ischemic injuries (Dirnagl et al. 2003; Stenzel-Poore et al. 2003; Dhodda et al. 2004; Koerner et al. 2007; Stenzel-Poore et al. 2007). We thus conducted the present study to test if the absence and presence of METH preconditioning might be also associated with METH-induced differential gene expression in the striatum, a brain region which is known to be affected by METH (Krasnova and Cadet 2009).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles Rivers Laboratories, Raleigh, NC), weighing 330–370 g in the beginning of the experiment were used in the present study. Animals were housed in a humidity- and temperature-controlled room and were given free access to food and water. All animal procedures were performed according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the local Animal Care Committee.

Drug Treatment and Tissue Collection.

Following habituation, rats were injected intraperitoneally with either (±)-METH-hydrochloride (NIDA, Baltimore, MD) or an equivalent volume of 0.9% saline for a period of three weeks as described elsewhere (Graham et al. 2008; Cadet et al. 2009a). The saline- or METH-pretreated animals received either saline or METH (5 mg/kg x 8 at 1 h intervals) challenges 72 hours after the preconditioning period. This dose of METH is known to cause significant decreases in the levels of monoamines in the rat striatum (Krasnova and Cadet 2009). The four groups of animals were: saline/saline (SS), saline/METH (SM), METH preconditioning/saline (MS), and METH preconditioning/METH (MM). The animals were euthanized 24 h after the injection of the last dose of METH. Their brains were quickly removed, brain regions were dissected on ice, snap frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C until used in microarray analyses or quantitative PCR experiments as described below.

RNA Extraction and Microarray Hybridization.

Total RNA was isolated using Qiagen RNeasy Midi kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA integrity was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) and showed no degradation. Microarray hybridization was carried out using Illumina’s RatRef-12 Expression BeadChips arrays (22, 227 probes) (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA). In brief, a 600 ng aliquot of total RNA from each striatal sample was amplified using Ambion’s Illumina RNA Amplification kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Single-stranded RNA (cRNA) was generated and labeled by incorporating biotin-16-UTP (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN). 750 ng of each cRNA sample were hybridized to Illumina arrays at 55 °C overnight according to the Illumina Whole-Genome Gene Expression Protocol for BeadStation (Illumina Inc.). Hybridized biotinylated cRNA was detected with cyanine3-streptavidine (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and quantified using Illumina’s BeadStation 500GX Genetic Analysis Systems scanner.

Microarray Data Analysis.

The raw data for the analyses of the four groups of animals are available upon request. The Illumina BeadStudio software was used to measure fluorescent hybridization signals. Data were extracted by BeadStudio (Illumina Inc.) and then analyzed using GeneSpring software v. 7.3.1 (Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA). Raw data were imported into GeneSpring and normalized using global normalization. The normalized data were used to identify changes in gene expression in four group comparisons: MS vs SS, SM vs SS, MM vs SS, and MM vs MS. A gene was identified as significantly changed if it showed increased or decreased expression according to an arbitrary cut-off of 1.7-fold changes at p < 0.025.

Real-time PCR.

Total RNA extracted from the rat striatum was also used to confirm the expression of genes of interest by real-time RT-PCR as previously described (Krasnova et al. 2007; Krasnova et al. 2008). In brief, unpooled total RNA obtained from 5–7 rats per group was reverse-transcribed with oligo dT primers and Advantage RT for PCR kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). PCR experiments were performed using light cycler technology and LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit (Roche) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Sequences for gene-specific primers corresponding to PCR targets were obtained using LightCycler Probe Design software (Roche). The primers were synthesized and HPLC-purified at the Synthesis and Sequencing Facility of Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). Quantitative PCR values were normalized using 18S rRNA and quantified. The results are reported as relative changes which were calculated as the ratios of normalized gene expression data of each group compared to the SS group.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher’s protected least significant difference post-hoc comparison (StatView 4.02, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Values are shown as means ± SEM. The null hypothesis was rejected at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Identification of genes regulated by METH preconditioning and by METH challenges in the rat striatum.

As reported elsewhere, METH preconditioning caused protection against METH-induced depletion in striatal DA and 5-HT levels (Cadet et al. 2009a). In order to assess transcriptional effects of toxic doses of METH in the rat striatum, we used Illumina RatRef-12 Expression BeadChips arrays that contain 22, 523 probes. The results of 3 comparisons between the four groups of rats: MS vs SS, SM vs SS, and MM vs MS are presented in the Venn diagram (Fig. 1). To be identified as changed, the genes had to show 1.7-fold difference with control expression at p < 0.025. A total of 230 genes were differentially impacted in the three comparisons, the distribution and overlap of these genes are shown in Fig. 1. Partial lists of these genes are given in tables 1–4.

FIGURE 1.

METH preconditioning induces differential striatal transcriptional responses to large doses METH. The Venn diagram shows the overlap of genes identified by the three sets of comparisons. The animals were injected and euthanized as described in the text. RNA was extracted from rat striatal tissues. The microarray experiments were performed as described in the method section. Genes were identified as significantly changed if they show greater than ±1.7-fold changes at p < 0.025.

TABLE 1.

Effects of METH preconditioning alone on striatal gene expression.

| Fold Changes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MS/SS | Gene Symbol | Common | Description |

| 18.32 | Adam18 | tMDCIII | a disintegrin and metallopeptidase domain 18 |

| 18.18 | Gabrr2 | Gabrr2 | gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA-C) receptor, subunit rho 2 |

| 13.91 | Sftpb | Sp-b | surfactant associated protein B |

| 11.89 | Fgf3 | Int2 | fibroblast growth factor 3 |

| 8.73 | Grpca | Grpca | glutamine/glutamic acid-rich protein A |

| 1.89 | Fmo2 | Fmo2 | flavin containing monooxygenase 2 |

| 1.75 | E2f1 | E2f1 | E2F transcription factor 1 |

| –1.71 | Lox | Rattus norvegicus lysyl oxidase (Lox), mRNA. | |

| –2.92 | Foxi2 | Fkhl5; Foxf1 | forkhead box I2 |

| –16.23 | Pcdhac1 | Pcdhac1; rCNRvc1 | protocadherin alpha subfamily C, 1 |

Data were obtained from the MS vs SS comparison. Predicted genes are not listed. The genes are listed in descending order according to METH-induced fold changes in gene expression.

TABLE 4.

Differential METH-induced striatal gene expression in the absence and presence of METH preconditioning.

| Fold Changes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (MM/SM) | Gene Symbol | Common | Description |

| 23.64 | Igsf7 | Igsf7; Mair-II | immunoglobulin superfamily, member 7 |

| 15.17 | Lif | Lif | leukemia inhibitory factor |

| 10.55 | Nanog | Nanog | Nanog homeobox |

| 7.40 | Fut11 | fucosyltransferase 11 | |

| 7.38 | Kcnq2 | Kcnq2 | potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily Q, member 2 |

| 1.88 | Chrna7 | BTX | cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 7 |

| 1.74 | Egfl6 | Egfl6 | EGF-like-domain, multiple 6 |

| −1.72 | Lxn | latexin | |

| −1.75 | Bdnf | brain derived neurotrophic factor | |

| −1.76 | Hgfac | Hgfac | hepatocyte growth factor activator |

| −1.79 | Abcb1b | Mdr1; Pgy1; Abcb1 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP), member 1B |

| −1.86 | Hcn1 | Hcn1 | hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated potassium channel 1 |

| −2.02 | Nr4a2 | Nurr1 | nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 |

| −2.07 | Hs3st2 | Hs3st2 | heparan sulfate (glucosamine) 3-O-sulfotransferase 2 |

| −2.61 | Klk8 | bsp1 | kallikrein 8 (neuropsin/ovasin) |

| −2.65 | Nov | Nov | nephroblastoma overexpressed gene |

| −2.77 | Cnga1 | HCN; Cncg | cyclic nucleotide gated channel alpha 1 |

| −11.10 | Npm2 | Npm2 | nucleophosmin/nucleoplasmin 2 |

| −20.75 | Neurod1 | Neurod1 | neurogenic differentiation 1 |

Data were obtained from the MM vs SM comparison. Predicted genes are not listed. The genes are listed in descending order according to the METH-induced fold changes.

Effects of METH preconditioning on striatal gene expression

Table 1 shows that chronic administration of low non-toxic doses of METH caused significant changes in the expression of 42 genes, with 30 being up-regulated and 12 down-regulated (MS vs SS). Of these genes, there were 34 that were found only in the MS vs SS comparison while 3 were found co-localized within the SM vs SS and 5 genes within the MM vs MS comparison. The most up-regulated gene was the predicted gene, Cd97, which showed 27-fold increases. (We are using only abbreviations in the text since the full name of the genes can be found in the tables that provide the list of METH-regulated genes). METH preconditioning caused 18-fold increases in the expression of Gabrr2 which is a receptor in GABA-mediated inhibitory synapses in the brain (Schmidt 2008). Another gene of interest is Fgf3, a member of the Fgf family of trophic factors (Itoh and Ornitz, 2008), which shows about 12-fold increases after repeated injections of non-toxic doses of METH.

Effects of METH challenges on striatal gene expression in the absence of METH preconditioning

Table 2 shows partial lists of genes affected by binge METH challenge in the striatum in the absence of METH preconditioning (SM vs SS). METH challenge caused significant changes in a total of 98 genes. Of these, 79 were up-regulated (Table 2) and 19 were down-regulated (not shown). The most significantly changed gene was Hcst which showed about a 45-fold increase. Other up-regulated genes of interest include Bcl2-like 10, Hsp27/HspB1, GFAP, Hmox-1, and caspase 4. GFAP expression has been shown to be induced by toxic doses of METH (Deng et al. 1999; Krasnova et al. 2010). The members of the Bcl2 family of mitochondrial proteins are also influenced by toxic doses of the drug (Jayanthi et al. 2001) and are involved in METH-induced neuronal apoptosis (Cadet et al. 1997). The expression of Hsp27/HspB1 (Jayanthi et al. 2009) and of Hmox-1 (Cadet et al. 2009b; Jayanthi et al. 2009) is also changed by toxic doses of METH. Some of these genes are similar to those reported by another group (Thomas et al., 2004).

TABLE 2.

METH-induced increases in striatal gene expression in the absence of METH preconditioning.

| Fold Changes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| SM/SS | Gene Symbol | Common | Description |

| 44.60 | Hcst | Hcst | hematopoietic cell signal transducer |

| 21.13 | Il1a | IL-1 alpha | interleukin 1 alpha |

| 15.80 | Lfng | Lfng | lunatic fringe gene homolog (Drosophila) |

| 14.83 | H19 | H19 | Rattus norvegicus H19 fetal liver mRNA (H19), misc RNA. |

| 12.53 | Bcl2l10 | Bcl2l10 | Bcl2-like 10 |

| 11.22 | Mb | Mb | myoglobin |

| 10.88 | Timp1 | Timp; TIMP-1 | tissue inhibitor of metallopeptidase 1 |

| 8.19 | Hspb1 | Hsp25; Hsp27 | heat shock 27kDa protein 1 |

| 4.83 | Cd44 | CD44A; METAA; RHAMM | CD44 antigen |

| 4.45 | Lcn2 | Lcn2 | lipocalin 2 |

| 4.41 | S100a3 | S100a3 | S100 calcium binding protein A3 |

| 3.05 | Fmo2 | Fmo2 | flavin containing monooxygenase 2 |

| 2.82 | Gfap | Gfap | Rattus norvegicus glial fibrillary acidic protein (Gfap), mRNA. |

| 2.74 | Pdpn | E11; Gp38; OTS-8; RTI40; T1-alpha | podoplanin |

| 2.67 | Emp3 | epithelial membrane protein 3 | |

| 2.64 | Serping1 | serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade G, member 1 | |

| 2.53 | Parp3 | Adprtl3 | poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase family, member 3 |

| 2.50 | Cd14 | Cd14 | CD14 antigen |

| 2.34 | Chi3l1 | Chi3l1 | chitinase 3-like 1 |

| 2.32 | Tyrobp | Karap | Tyro protein tyrosine kinase binding protein |

| 2.28 | Gpd1 | GPDH; Gpd3 | glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 (soluble) |

| 2.25 | Tmbim1 | transmembrane BAX inhibitor motif containing 1 | |

| 2.20 | Nes | Nes | nestin |

| 2.17 | Cox6a2 | COX6B; COX6AH | cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIa, polypeptide 2 |

| 2.16 | Prelp | Prelp | proline arginine-rich end leucine-rich repeat protein |

| 2.13 | Plp2 | A4-LSB | proteolipid protein 2 |

| 2.12 | C1qb | C1qb | complement component 1, q subcomponent, beta polypeptide |

| 2.02 | Ptpn6 | Ptph6; Shp-1 | protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 6 |

| 1.96 | Sv2c | Sv2c | synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2c |

| 1.95 | Prkcdbp | Srbc; DIG-2 | protein kinase C, delta binding protein |

| 1.95 | Vamp5 | Vamp5 | vesicle-associated membrane protein 5 |

| 1.95 | S100a4 | CAPL; MTS1 | S100 calcium-binding protein A4 |

| 1.93 | Fxyd5 | RIC | FXYD domain-containing ion transport regulator 5 |

| 1.92 | Ddit4l | Ddit4l | DNA-damage-inducible transcript 4-like (Ddit4l), mRNA. |

| 1.92 | Col5a1 | Col5a1 | procollagen, type V, alpha 1 |

| 1.90 | Fgfrl1 | Fgfr5 | fibroblast growth factor receptor-like 1 |

| 1.90 | Arf6 | Arf6 | ADP-ribosylation factor 6 |

| 1.89 | Hla-dma | RT1-DMa; RT1.DMa | major histocompatibility complex, class II, DM alpha |

| 1.89 | Pycard | Asc | PYD and CARD domain containing |

| 1.85 | Cdo1 | Cdo1 | cysteine dioxygenase 1, cytosolic |

| 1.84 | Clic1 | Clic1 | chloride intracellular channel 1 |

| 1.82 | Ccl21b | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 21b (serine) | |

| 1.81 | Stat3 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 | |

| 1.80 | Hmox1 | Ho1; Heox; Hmox; Ho-1; HEOXG; hsp32 | heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 |

| 1.79 | Chek2 | Chk2; Rad53 | CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) |

| 1.79 | Casp4 | Casp11 | caspase 4, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase |

| 1.76 | Eif4ebp1 | PHAS-I | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 |

| 1.74 | Tgfb1 | Tgfb1 | transforming growth factor, beta 1 |

| 1.73 | Lgals3 | gal-3 | lectin, galactose binding, soluble 3 |

| 1.71 | ZnT3 | Slc30a3 | solute carrier family 30 (zinc transporter), member 3 |

| 1.70 | Emp1 | TMP; CL-20; EMP-1; ENP1MR | epithelial membrane protein 1 |

The data were generated from the SM vs SS comparison. Predicted genes are not included. The genes are listed in descending order according to fold changes in gene expression.

Effects of METH challenges on striatal gene expression in the presence of METH preconditioning

Table 3 shows a partial list of genes whose expression was affected by the injections of large doses of METH in the presence of METH preconditioning (MM vs MS). Ninety genes were affected in that comparison. Of these, 32 were up-regulated and 58 were down-regulated by the large dose METH challenge. Sixty seven of these genes were changed only after METH challenge in the striata of rats preconditioned with METH while 18 genes were also contained in the MM vs MS comparison (Fig. 1). In addition, 5 genes showed changes in expression in the MS vs SS comparison. The most up-regulated gene was H19. Other up-regulated genes of interest include Timp1, Nes, GFAP, and Vgf. HspB1 which was up-regulated in the absence of METH preconditioning is also up-regulated in the MM vs MS comparison, but to a lesser extent. In contrast, S100a3 and GFAP were up-regulated to similar extent in the absence or presence of METH preconditioning.

TABLE 3.

METH-induced changes in striatal gene expression in the presence of METH preconditioning.

| Fold Changes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (MM/MS) | Gene Symbol | Common | Description |

| 13.43 | H19 | Rattus norvegicus H19 fetal liver mRNA (H19), misc RNA. | |

| 11.12 | Gys2 | GLYSN | glycogen synthase 2 |

| 5.67 | Timp1 | Timp; TIMP-1 | tissue inhibitor of metallopeptidase 1 |

| 4.47 | Hspb1 | Hsp25; Hsp27 | heat shock 27kDa protein 1 |

| 3.50 | Cd44 | CD44A; METAA | CD44 antigen |

| 3.30 | S100a3 | S100a3 | S100 calcium binding protein A3 |

| 2.95 | Cxcl10 | IP-10; Scyb10 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 |

| 2.20 | Nes | Nes | nestin |

| 2.19 | Gfap | Gfap | Rattus norvegicus glial fibrillary acidic protein (Gfap), mRNA. |

| 2.18 | Pdpn | E11; Gp38; OTS-8 | podoplanin |

| 1.94 | Chi3l1 | Chi3l1 | chitinase 3-like 1 |

| 1.83 | Tmbim1 | transmembrane BAX inhibitor motif containing 1 | |

| 1.82 | Tyrobp | Karap | Tyro protein tyrosine kinase binding protein |

| 1.81 | Vgf | Vgf | VGF nerve growth factor inducible |

| 1.81 | Serping1 | serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade G, member 1 | |

| 1.76 | Prelp | Prelp | proline arginine-rich end leucine-rich repeat protein |

| −1.72 | Slc4a1 | solute carrier family 4, member 1 | |

| −1.75 | Gucy1b2 | SGC; Gucy1b2a; Gucy1b2b | guanylate cyclase 1, soluble, beta 2 |

| −1.75 | Grem1 | drm; Cktsf1b1 | gremlin 1 homolog, cysteine knot superfamily (Xenopus laevis) |

| −1.79 | Ces2 | rCES2; CES RL4 | carboxylesterase 2 (intestine, liver) |

| −1.81 | Hcn1 | Hcn1 | hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated potassium channel 1 |

| −1.86 | Sstr1 | Rattus norvegicus somatostatin receptor 1 (Sstr1), mRNA. | |

| −1.87 | Ahr | Rattus norvegicus aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr), mRNA. | |

| −1.94 | Rnasel | Rnasel | ribonuclease L (2’,5’-oligoisoadenylate synthetase-dependent) |

| −1.95 | Pnck | Camk1b | pregnancy upregulated non-ubiquitously expressed CaM kinase |

| −2.13 | Slit1 | Rattus norvegicus slit homolog 1 (Drosophila) (Slit1), mRNA. | |

| −3.37 | Rtn4r | Rattus norvegicus reticulon 4 receptor (Rtn4r), mRNA. | |

| −4.18 | St8sia6 | Siat8f | ST8 alpha-N-acetyl-neuraminide alpha-2,8-sialyltransferase 6 |

| −14.21 | Arl10 | Arl10 | ADP-ribosylation factor-like 10 |

| −15.94 | Nfatc2ip | nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic, calcineurin-dependent 2 interacting protein | |

| −20.45 | Dnase1l3 | deoxyribonuclease I-like 3 | |

| −27.30 | Cldn3 | Cldn3 | claudin 3 |

| −30.18 | Ntn2l | Ntn3 | netrin 2-like (chicken) |

| −42.53 | Pla2g1b | Pla2g1b | phospholipase A2, group IB |

| −44.28 | Col23a1 | Col23a1 | procollagen, type XXIII, alpha 1 |

The data were generated from the MM vs MS comparison. Predicted genes are not included. The genes are listed in descending order according to fold changes in gene expression.

Differential METH-induced striatal gene expression in the absence and presence of METH preconditioning

In order to dissect the effects of METH preconditioning further, we compared the levels of gene expression between the MM and the SM groups (MM vs SM). We found that 77 genes were affected, with 36 being up-regulated and 41 down-regulated. Table 4 shows a partial list of these genes. The most up-regulated gene was Igsf7. Other up-regulated genes of interest include Lif and Egfl6. Down-regulated genes of interest include BDNF and Nurr1.

Quantitative PCR for genes of interest

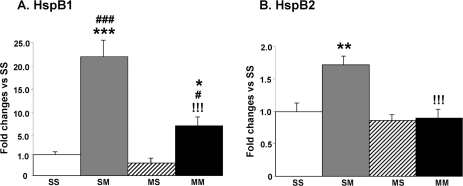

We examined METH-induced changes in the expression of Hsp27/HspB1 which was up-regulated to differential degrees in both the SM and MM groups in the microarray experiments. METH injections caused about 22- and 7-fold increases in the levels of Hsp27/HspB1 mRNA in the SM and MM groups, respectively (Fig. 2A). The changes observed in the MM were significantly less pronounced than those observed in the SM group. We also measured the expression of HspB2, another member of the HspB family of small heat shock proteins (sHSPs) (Hu et al. 2008) which has been shown to exert protection against ischemia-induced damage (Morrison et al. 2004). The METH injections caused significant increases in HspB2 mRNA levels in the absence but not in the presence of METH preconditioning (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Quantitative PCR validates the effects of large doses of METH on striatal HspB1 and HspB2 mRNA levels. Data were obtained using RNA isolated from 5–6 animals per group and measured individually. The mRNA levels were normalized to 18S rRNA levels. The values are shown as means ± SEM in comparison to the SS group. METH caused substantial increases in (A) HspB1 in both the SM and MM groups and (B) HspB2 only in the SM group. Keys to statistics: *, **, *** p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, respectively, in comparison to the SS group; #, ### p < 0.05, 0.001, respectively, in comparison to the MS group; !!!, p < 0.001, in comparison to the SM group.

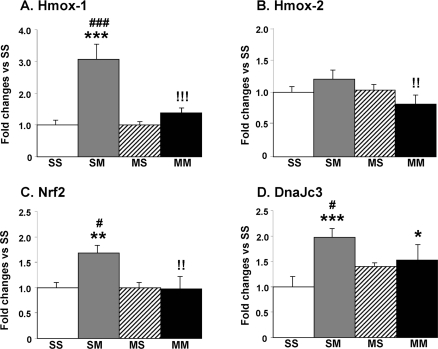

The PCR experiments also confirmed that the expression of Hmox-1 was up-regulated in the SM but not in the MM group (Fig. 3A). In addition, we also measured the expression of Hmox-2, another member of the Hmox family even though it was not identified as being regulated by METH in the microarray data. As shown in Fig. 3B, there were small decreases in the MM group which were significantly different from the SM group. Because Hmox-1 expression is regulated by NRF2 protein translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus (Surh et al. 2009), we tested the idea that multiple injections of METH might cause increases in Nrf2 mRNA. We found that the METH challenge did cause increases in Nrf2 expression in the absence (SM) but not in the presence of METH preconditioning (MM) (Fig. 3C). Because Hmox-1 is up-regulated by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (Gozzelino et al. 2010), we also tested the possibility that DnaJc3 (p58IPK) which is involved in protecting cells against ER stress (Rutkowski et al. 2007) might be induced by METH. Indeed, the large METH doses caused significant increases in DnaJc3 expression in the absence but not in the presence of METH preconditioning (Fig. 3D).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of large doses of METH on striatal Hmox-1, Hmox-2, Nrf2, and DnaJc3 mRNA levels. Data were obtained using RNA isolated from 5–6 animals per group and measured individually. The mRNA levels were normalized to 18S rRNA levels. The values are means ± SEM in comparison to the SS group. METH caused substantial increases in (A) Hmox-1 in the SM group but not in (B) Hmox-2. There were also METH-induced increases in the expression of (C) Nrf2 in the SM group and of (D) DnaJc3 in both the SM and MM groups. Keys to statistics: *, **, *** p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, respectively, in comparison to the SS group; #, ### p < 0.05, 0.001, respectively, in comparison to the MS group; !!, !!!, p < 0.001, respectively, in comparison to the SM group.

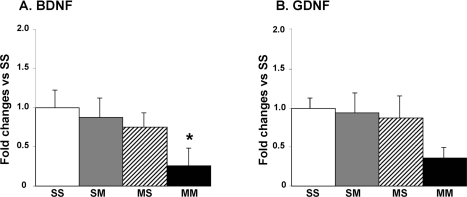

Because the microarray experiments identified BDNF as being down-regulated in the MM in comparison to the SM group and because BDNF has been shown to provide protection against transneuronal degeneration of DA neurons (Canudas et al. 2005), we sought to confirm these data by quantitative PCR. Figure 4A shows that there were significant decreases in BDNF expression in the presence of METH preconditioning (MM group). We also measured the expression of GDNF that has been shown to protect against METH toxicity (Cass et al. 2006). There were some decreases in GDNF mRNA levels in MM group that did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Effects of large doses of METH on striatal BDNF and GDNF mRNA levels. Tissues were processed and mRNA levels measured as described in the text. METH caused significant decreases in (A) BDNF in MM group. (B) GDNF expression was not significantly affected in any of the groups. Keys to statistics: * p < 0.05, in comparison to the SS group.

DISCUSSION

The main findings in these experiments are that acute injections of large doses of METH caused differential gene expression in the striata of rats depending on whether the animals have been pre-exposed repeatedly to smaller non-toxic doses of the drug or not. The present observations allowed for the creation of differentially expressed genes after exposure to large doses of METH. These results are important because there are very few reports on the effects of chronic METH treatment on large scale gene expression in the rat striatum. We hope that the results of our study will provide a comprehensive database for future investigations of METH preconditioning, METH toxicity, and drug-induced neuroplastic changes in the rat striatum.

In this study, we found that the vast majority of genes regulated by the single-day binge METH injections are different from those regulated by acute METH injections (Cadet et al. 2001; Jayanthi et al. 2009). These differences might be due to the fact that data reported in the previous studies were obtained from animals euthanized within the first 4 hours after the METH injections (Cadet et al. 2001; Jayanthi et al. 2009). It is important to point out that the genes identified in the striatum are also different from the genes identified in the midbrain after METH preconditioning, indicating that the preconditioning process might be regionally specific in terms of METH-induced gene expression (Cadet et al. 2009b). These regional differences might be secondary to the fact that the data of the former study came from the rat midbrain which is the site of origin for dopaminergic neurons whereas the present data were obtained from intrinsic striatal non-dopaminergic neurons. Nevertheless, our data support the idea that METH preconditioning is associated with significant alterations of the striatal transcriptional responses to large doses of METH. In what follows, we discuss the role of some interesting genes whose METH-induced changes in expression were confirmed by quantitative PCR.

Mammalian HSPs, which include Hsp27/HspB1, are molecular chaperones that participate in the proper folding of proteins and help to maintain their native conformations during stressful events (Arya et al. 2007). Hsp27/HspB1 is a novel regulator of intracellular redox state (Arrigo 2007). HSPs also participate in the transfer of improperly folded proteins to the proteasome for degradation. HSPs are induced by heat shock, hypoxic and ischemic events, and oxidative stress (Arrigo 2007; Arya et al. 2007). Recent studies have documented a role for these proteins in neurodegenerative processes and have demonstrated that HSPs are important in cellular protection against aggregation-prone proteins and in animal models of neurodegeneration (Muchowski and Wacker 2005). Thus, our demonstration of METH-induced expression of the chaperones, Hsp27/HspB1 (Franklin et al. 2005) and HspB2 (Hu et al. 2008), suggests that striatal cells are able to mount adaptive defensive HSP-modulated networks against the toxic effects of the drug. Hsp27/HspB1 appears to exert its protective effects, in part, by inhibiting caspase-dependent apoptotic pathways (Garrido et al. 1999; Voss et al. 2007).

We also found that the METH challenge caused 3-fold increases in Hmox-1 expression in the absence of METH preconditioning and that these increases were attenuated in the striata of the METH preconditioned rats. Because Hmox-1 is an enzyme that can be induced by oxidative stress (Calabrese et al. 2004; Li et al. 2007) and because METH toxicity is mediated, in part, via oxidative stress (Krasnova and Cadet 2009), the present observations suggest that the METH challenge might have caused more oxidative stress in the striata of animals pretreated with saline. However, since saline-pretreated animals do show METH toxicity, these METH-induced increases in Hmox-1 might not be sufficient to protect post-synaptic cells from drug-related damage. It is important to point that overexpression of Hmox-1 can protect against METH toxicity in vitro (Huang et al. 2009). Nevertheless, it appears that a substantial increase in the level of the enzyme might be necessary before protection against METH toxicity can be observed in vivo. This remains to be demonstrated.

The expression of BDNF which is involved in the regulation of cell survival (Canudas et al. 2005) and in synaptic plasticity (Kuipers and Bramham 2006), was significantly decreased by the METH challenge only in the presence of METH preconditioning. These results were unexpected since we had observed increases in BDNF expression in the midbrain where the DA neurons are located (Cadet et al. 2009b). The present observations in the rat striatum suggest that the increases in BDNF in midbrain dopaminergic neurons might cause increases in the release of BDNF in the striatum and compensatory down-regulation of its expression in intrinsic striatal cells via epigenetic changes in the regulation of BDNF through promoter methylation (Dennis and Levitt 2005). These epigenetic changes might also involve decreased recruitment of acetylated histones on BDNF promoters since histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors have been reported to cause increases in BDNF transcription (Wu et al. 2008). In any case, these dichotomous results in the terminal regions and in the cell body area emphasize the need to determine regional effects of toxic agents on the brain.

This discussion also applies to the effects of METH on striatal Hspb2 and Hmox1 mRNA levels which showed increases in response to the challenge with high doses of METH in the absence but not in the presence of METH preconditioning. The situation was reversed in the midbrain of these animals because METH preconditioning enhanced the METH challenge-induced increases in Hspb2 and Hmox-1 mRNA levels in the rat midbrain (Cadet et al., 2009b). These results support our thesis that the brain cannot be thought of as a homogeneous structure when assessing the molecular effects of preconditioning and/or toxic compounds.

In summary, we found that the challenge with large doses of METH is associated with differential transcriptional responses in the rat striatum in the absence and presence of preconditioning with repeated injections of small nontoxic doses of the drug. These results suggest that intrinsic striatal cells exposed to low METH doses develop a certain degree of tolerance to the effects of the drug on the expression of genes that are triggering the nefarious METH effects. Future studies are underway to test the possibility that METH preconditioning can also protect against METH-induced cell death in the striatum.

Acknowledgments

The study is supported by Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH, DHHS.

REFERENCES

- Arrigo AP. The cellular “networking” of mammalian Hsp27 and its functions in the control of protein folding, redox state and apoptosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;594:14–26. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-39975-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya R, Mallik M, Lakhotia SC. Heat shock genes - integrating cell survival and death. J Biosci. 2007;32:595–610. doi: 10.1007/s12038-007-0059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet JL, Krasnova IN. Cellular and molecular neurobiology of brain preconditioning. Mol Neurobiol. 2009;39:50–61. doi: 10.1007/s12035-009-8051-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet JL, Sheng P, Ali S, Rothman R, Carlson E, Epstein C. Attenuation of methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity in copper/zinc superoxide dismutase transgenic mice. J Neurochem. 1994;62:380–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62010380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet JL, Ordonez SV, Ordonez JV. Methamphetamine induces apoptosis in immortalized neural cells: protection by the proto-oncogene, bcl-2. Synapse. 1997;25:176–184. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199702)25:2<176::AID-SYN8>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet JL, Jayanthi S, McCoy MT, Vawter M, Ladenheim B. Temporal profiling of methamphetamine-induced changes in gene expression in the mouse brain: evidence from cDNA array. Synapse. 2001;41:40–48. doi: 10.1002/syn.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet JL, Jayanthi S, Deng X. Speed kills: cellular and molecular bases of methamphetamine-induced nerve terminal degeneration and neuronal apoptosis. Faseb J. 2003;17:1775–1788. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0073rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet JL, Krasnova IN, Jayanthi S, Lyles J. Neurotoxicity of substituted amphetamines: molecular and cellular mechanisms. Neurotox Res. 2007;11:183–202. doi: 10.1007/BF03033567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet JL, Krasnova IN, Ladenheim B, Cai NS, McCoy MT, Atianjoh FE. Methamphetamine preconditioning: differential protective effects on monoaminergic systems in the rat brain. Neurotox Res. 2009a;15:252–259. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9026-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet JL, McCoy MT, Cai NS, Krasnova IN, Ladenheim B, Beauvais G, Wilson N, Wood W, Becker KG, Hodges AB. Methamphetamine preconditioning alters midbrain transcriptional responses to methamphetamine-induced injury in the rat striatum. PLoS One. 2009b;4:e7812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese EJ. Converging concepts: adaptive response, preconditioning, and the Yerkes-Dodson Law are manifestations of hormesis. Ageing Res Rev. 2008;7:8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese V, Stella AM, Butterfield DA, Scapagnini G. Redox regulation in neurodegeneration and longevity: role of the heme oxygenase and HSP70 systems in brain stress tolerance. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6:895–913. doi: 10.1089/ars.2004.6.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canudas AM, Pezzi S, Canals JM, Pallas M, Alberch J. Endogenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor protects dopaminergic nigral neurons against transneuronal degeneration induced by striatal excitotoxic injury. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;134:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass WA, Peters LE, Harned ME, Seroogy KB. Protection by GDNF and other trophic factors against the dopamine-depleting effects of neurotoxic doses of methamphetamine. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1074:272–281. doi: 10.1196/annals.1369.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Alicata D, Ernst T, Volkow N. Structural and metabolic brain changes in the striatum associated with methamphetamine abuse. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 1):16–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danaceau JP, Deering CE, Day JE, Smeal SJ, Johnson-Davis KL, Fleckenstein AE, Wilkins DG. Persistence of tolerance to methamphetamine-induced monoamine deficits. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;559:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Kaye S, McKetin R, Duflou J. Major physical and psychological harms of methamphetamine use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27:253–262. doi: 10.1080/09595230801923702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Ladenheim B, Tsao LI, Cadet JL. Null mutation of c-fos causes exacerbation of methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10107–10115. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-10107.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis KE, Levitt P. Regional expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is correlated with dynamic patterns of promoter methylation in the developing mouse forebrain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;140:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhodda VK, Sailor KA, Bowen KK, Vemuganti R. Putative endogenous mediators of preconditioning-induced ischemic tolerance in rat brain identified by genomic and proteomic analysis. J Neurochem. 2004;89:73–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirnagl U, Simon RP, Hallenbeck JM. Ischemic tolerance and endogenous neuroprotection. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:248–254. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TB, Krueger-Naug AM, Clarke DB, Arrigo AP, Currie RW. The role of heat shock proteins Hsp70 and Hsp27 in cellular protection of the central nervous system. Int J Hyperthermia. 2005;21:379–392. doi: 10.1080/02656730500069955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido C, Bruey JM, Fromentin A, Hammann A, Arrigo AP, Solary E. HSP27 inhibits cytochrome c-dependent activation of procaspase-9. Faseb J. 1999;13:2061–2070. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.14.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozzelino R, Jeney V, Soares MP. Mechanisms of cell protection by heme oxygenase-1. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:323–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham DL, Noailles PA, Cadet JL. Differential neurochemical consequences of an escalating dose-binge regimen followed by single-day multiple-dose methamphetamine challenges. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1873–1885. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Yang B, Lu W, Zhou W, Zeng L, Li T, Wang X. HSPB2/MKBP, a novel and unique member of the small heat-shock protein family. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:2125–2133. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YN, Wu CH, Lin TC, Wang JY. Methamphetamine induces heme oxygenase-1 expression in cortical neurons and glia to prevent its toxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;240:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh N, Ornitz DM. Functional evolutionary history of the mouse Fgf gene family. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:18–27. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi S, Deng X, Bordelon M, McCoy MT, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine causes differential regulation of pro-death and anti-death Bcl-2 genes in the mouse neocortex. Faseb J. 2001;15:1745–1752. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0025com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi S, McCoy MT, Beauvais G, Ladenheim B, Gilmore K, Wood W, 3rd, Becker K, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine induces dopamine D1 receptor-dependent endoplasmic reticulum stress-related molecular events in the rat striatum. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Davis KL, Fleckenstein AE, Wilkins DG. The role of hyperthermia and metabolism as mechanisms of tolerance to methamphetamine neurotoxicity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;482:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerner IP, Gatting M, Noppens R, Kempski O, Brambrink AM. Induction of cerebral ischemic tolerance by erythromycin preconditioning reprograms the transcriptional response to ischemia and suppresses inflammation. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:538–547. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200703000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JC, Fischman VS, Littlefield DC. Amphetamine abuse. Pattern and effects of high doses taken intravenously. Jama. 1967;201:305–309. doi: 10.1001/jama.201.5.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova IN, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60:379–407. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova IN, Betts ES, Dada A, Jefferson A, Ladenheim B, Becker KG, Cadet JL, Hohmann CF. Neonatal dopamine depletion induces changes in morphogenesis and gene expression in the developing cortex. Neurotox Res. 2007;11:107–130. doi: 10.1007/BF03033390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova IN, Li SM, Wood WH, McCoy MT, Prabhu VV, Becker KG, Katz JL, Cadet JL. Transcriptional responses to reinforcing effects of cocaine in the rat hippocampus and cortex. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova IN, Justinova Z, Ladenheim B, Jayanthi S, McCoy MT, Barnes C, Warner JE, Goldberg SR, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine self-administration is associated with persistent biochemical alterations in striatal and cortical dopaminergic terminals in the rat. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers SD, Bramham CR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor mechanisms and function in adult synaptic plasticity: new insights and implications for therapy. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2006;9:580–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladenheim B, Krasnova IN, Deng X, Oyler JM, Polettini A, Moran TH, Huestis MA, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity is attenuated in transgenic mice with a null mutation for interleukin-6. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:1247–1256. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Hossieny P, Wu BJ, Qawasmeh A, Beck K, Stocker R. Pharmacologic induction of heme oxygenase-1. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:2227–2239. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison LE, Whittaker RJ, Klepper RE, Wawrousek EF, Glembotski CC. Roles for alphaB-crystallin and HSPB2 in protecting the myocardium from ischemia-reperfusion-induced damage in a KO mouse model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H847–855. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00715.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchowski PJ, Wacker JL. Modulation of neurodegeneration by molecular chaperones. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JB. Psychophysiological aspects of amphetamine-methamphetamine abuse. J Psychol. 1998;132:227–237. doi: 10.1080/00223989809599162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrenovitch TP. Molecular physiology of preconditioning-induced brain tolerance to ischemia. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:211–247. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski DT, Kang SW, Goodman AG, Garrison JL, Taunton J, Katze MG, Kaufman RJ, Hegde RS. The role of p58IPK in protecting the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3681–3691. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-03-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. GABA(C) receptors in retina and brain. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2008;44:49–67. doi: 10.1007/400_2007_031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JC, Woods SP, Matt GE, Meyer RA, Heaton RK, Atkinson JH, Grant I. Neurocognitive effects of methamphetamine: a critical review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007;17:275–297. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine Y, Minabe Y, Ouchi Y, Takei N, Iyo M, Nakamura K, Suzuki K, Tsukada H, Okada H, Yoshikawa E, Futatsubashi M, Mori N. Association of dopamine transporter loss in the orbitofrontal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices with methamphetamine-related psychiatric symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1699–1701. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine Y, Ouchi Y, Takei N, Yoshikawa E, Nakamura K, Futatsubashi M, Okada H, Minabe Y, Suzuki K, Iwata Y, Tsuchiya KJ, Tsukada H, Iyo M, Mori N. Brain serotonin transporter density and aggression in abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:90–100. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine Y, Ouchi Y, Sugihara G, Takei N, Yoshikawa E, Nakamura K, Iwata Y, Tsuchiya KJ, Suda S, Suzuki K, Kawai M, Takebayashi K, Yamamoto S, Matsuzaki H, Ueki T, Mori N, Gold MS, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine causes microglial activation in the brains of human abusers. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5756–5761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1179-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon SL, Domier CP, Sim T, Richardson K, Rawson RA, Ling W. Cognitive performance of current methamphetamine and cocaine abusers. J Addict Dis. 2002;21:61–74. doi: 10.1300/j069v21n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel-Poore MP, Stevens SL, Xiong Z, Lessov NS, Harrington CA, Mori M, Meller R, Rosenzweig HL, Tobar E, Shaw TE, Chu X, Simon RP. Effect of ischaemic preconditioning on genomic response to cerebral ischaemia: similarity to neuroprotective strategies in hibernation and hypoxia-tolerant states. Lancet. 2003;362:1028–1037. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14412-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel-Poore MP, Stevens SL, King JS, Simon RP. Preconditioning reprograms the response to ischemic injury and primes the emergence of unique endogenous neuroprotective phenotypes: a speculative synthesis. Stroke. 2007;38:680–685. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251444.56487.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surh YJ, Kundu JK, Li MH, Na HK, Cha YN. Role of Nrf2-mediated heme oxygenase-1 upregulation in adaptive survival response to nitrosative stress. Arch Pharm Res. 2009;32:1163–1176. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-1807-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DM, Francescutti-Verbeem DM, Liu X, Kuhn DM. Identification of differentially regulated transcripts in mouse striatum following methamphetamine treatment-an oligonucleotide microarray approach. J Neurochem. 2004;88:380–393. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DM, Kuhn DM. Attenuated microglial activation mediates tolerance to the neurotoxic effects of methamphetamine. J Neurochem. 2005;92:790–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Leonido-Yee M, Franceschi D, Sedler MJ, Gatley SJ, Hitzemann R, Ding YS, Logan J, Wong C, Miller EN. Association of dopamine transporter reduction with psychomotor impairment in methamphetamine abusers. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:377–382. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss OH, Batra S, Kolattukudy SJ, Gonzalez-Mejia ME, Smith JB, Doseff AI. Binding of caspase-3 prodomain to heat shock protein 27 regulates monocyte apoptosis by inhibiting caspase-3 proteolytic activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25088–25099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Chen PS, Dallas S, Wilson B, Block ML, Wang CC, Kinyamu H, Lu N, Gao X, Leng Y, Chuang DM, Zhang W, Lu RB, Hong JS. Histone deacetylase inhibitors up-regulate astrocyte GDNF and BDNF gene transcription and protect dopaminergic neurons. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:1123–1134. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweben JE, Cohen JB, Christian D, Galloway GP, Salinardi M, Parent D, Iguchi M. Psychiatric symptoms in methamphetamine users. Am J Addict. 2004;13:181–190. doi: 10.1080/10550490490436055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]