Abstract

Background

Although national findings regarding people's end-of-life care (EoLC) preferences and priorities are available within Europe, a lack of research coordination between countries has meant that cross-national understandings of EoLC remain unknown.

Purpose

To (1) identify English and German understandings of EoLC within the context of an EoLC survey, and (2) to synthesise these understandings to aid interpretation of results from a cross-national survey.

Methods

An inductive and interpretive two-phased sequential design involving (1) qualitative analysis of cognitive interview data from 15 English and 15 German respondents to develop country-related categories, and (2) qualitative synthesis to identify a conceptually coherent understanding of EoLC.

Results

Open and axial coding resulted in six English and six German categories. Commonalities included (a) the importance of social and relational dimensions, (b) dynamic decision making comprising uncertainty, (c) a valuing of life's quality and quantity, and (d) expectations for holistic care involving autonomy, choice, and timely information from trusted professionals. Differences involved attention to practical matters, and thoughts about prolongation of life, preferred place of death, and the role of media and context. Synthesis resulted in four concepts with underlying coherence: expectations of a high standard of EoLC involving autonomy, choice, and context; evolving decision making amid anticipated change; thoughts about living and existing; and worldviews shaping EoLC preferences in real and hypothetical scenarios.

Conclusion

Individual and country-related diversity must be remembered when quantifying EoLC understandings. Inductive-interpretive analysis of cognitive interview data aids interpretation of survey findings. Cross-national research coordination and qualitative synthesis assists EoLC in Europe.

Introduction

In some European countries less than 0.5% of research spending in cancer is allocated to end-of-life care (EoLC) and palliative care.1 National surveys and systematic reviews provide useful information regarding EoLC preferences,2–4 although a lack of research coordination between countries makes cross-national comparison difficult. EoLC is an immense public health matter involving a need for planning to accommodate a large increase in aging and deaths. Cross-national effort is needed to aid European EoLC policy, education, and research. PRISMA, a project funded by the European Commission under Framework Programme Seven, aims to coordinate high-quality research regarding EoLC across Europe. One PRISMA objective is to conduct a pan-European public survey of EoLC priorities and preferences.5 Before administering this survey and as an essential survey-development step, cognitive interviewing was used to improve PRISMA's survey questions.

Cognitive interviewing is an increasingly prominent step involved in survey design6,7 and is recommended for use in palliative care.8 Various cognitive interviewing approaches and procedures can be used, such as think-aloud and probe-based procedures, and concurrent and retrospective approaches. In its essence cognitive interviewing involves collecting respondents' thoughts and feelings to identify and correct difficulties in survey items by determining whether each question generates the required information.6 We proposed that additional analysis of our data could result in an enhanced understanding of EoLC, aiding our interpretation of the pan-European survey findings.

Consequently, in addition to analysis for survey-item development, we examined what members of the English and German public understand by EoLC through analysing their cognitive interview responses inductively. Our research question was How is EoLC understood by our English and German respondents, and what is their shared understanding? Our objectives were to: (1) identify country-related understandings of EoLC, and (2) to construct a cross-country understanding through qualitative synthesis. A conceptually coherent, cross-national understanding resulted from our novel methodological approach, which is presented here, responding to a need for coordinated cross-country research efforts for EoLC in Europe.

Method

Design and analysis

An interpretive ontology9,10 informed our inductive, two-phased, sequential research design. This interpretive perspective allowed for the analysis of socially and experientially developed responses, including perceptions of EoLC. Data were analysed in two phases by experienced researchers working in parallel within two teams.

In phase one, grounded theory principles guided the coding of cognitive interview data to determine categories for two separate respondent groups (English and German). This modified grounded theory analytical approach involved open and axial coding to identify phenomena and establish categories.11–13 Theory development was not the anticipated research outcome of this study and therefore grounded theory in its “complete” form was not required nor completed. In each research team at least one native-speaking researcher analysed the German (DBE) and English language (BD) data. During coding, the two research teams met separately to review emerging categories in their source language, ensuring: (a) theoretical sensitivity through analysis of source-language data, (b) comprehensive and systematic coding, (c) deviant case inclusion, and (d) logical representation of codes and transcripts.

In phase two, the English and German sets of findings were synthesised through a lines-of-argument meta-ethnography, as described by Noblit and Hare,10 through: (a) identifying and defining key concepts from the primary findings; (b) translating country-related concepts through comparing, contrasting, and reinterpretation; and (c) repositioning similarities and differences into a new interpretive order to form one cohesive interpretative outcome. As a combined conceptual understanding was required from this phase rather than theory and ongoing theoretical sampling was also not possible, meta-ethnographic synthesis was conducted rather than ongoing open and axial coding. Noblit and Hare explain that new synthesized understandings can result from reinterpreting concepts/metaphors of primary findings (including from their own studies), allowing anticipation (not prediction) of what might be involved in analogous situations.

An audit trail was maintained to aid researcher awareness, reflexivity, and transparency.9, 12–15 Source-language analysis enhanced theoretical sensitivity. Whole sentences/paragraphs were coded, context-related information, and subjective meaning was retained within codes, and complexity of meaning was supported through the option of assigning more than one code to a section of data. Translation and synthesis of concepts was aided by consultation of transcripts. Ethical approval was granted in the UK (Biomedical and Health Sciences, Dentistry, Medicine and Physical Sciences & Engineering (BDM)/08/09–48). The national German medical ethics committee and data protection agency were informed of the study, advising that approval from them was not required.

Sample

Interviews were conducted from the UK using each respondent's native tongue of German or English. Individuals aged 16 years or more, able to consent and participate in an interview were eligible to participate. Within a convenience sampling frame, purposive sampling was used for variation in age, gender, and ethnicity. Lay individuals known to the researchers were invited for interview. Snowball sampling was also used with respondents nominating others for interview.15

Cognitive interviews

PRISMA's EoLC survey consisted of 13 survey questions regarding preferred place of death, information, and decision making, for example: If you had a serious illness, for example cancer, and were likely to have less than one year to live, would you like to be informed that you had limited time left? For each respondent group, 5 cognitive interviews were conducted while answering these 13 survey questions, and a further 10 interviews were conducted after survey completion. The telephone cognitive interviews were partially scripted beforehand. The script consisted of 13 interview questions, including: What do you understand by serious illness? What do you understand by end-of-life care? Interview questions were supplemented by spontaneous probing. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, anonymized, and imported into NVivo software version 8 (QSR International Inc.).

Results

Approximately 11 hours of data resulted for the English respondents, and 13 hours for the German. Respondents' age, gender, ethnicity, and religion are provided in Table 1, alongside experiences of serious illness, death, and dying. Six categories from the English and six from the German resulted, shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| |

|

UK |

Germany |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of respondents | 15 | 15 | |

| Age | Median | 61 | 45 |

| Range | 17–81 | 19–81 | |

| Gender | Female | 8 | 10 |

| Male | 7 | 5 | |

| Ethnicity | British or German | 10 | 13 |

| European | 2 | 0 | |

| Turkish | 1 | 2 | |

| Indian | 1 | 0 | |

| Chinese | 1 | 0 | |

| Religious and religion | No, not religious | 5 | 3 |

| Yes, religious | 10 | 12 | |

| Religious affiliation | |||

| Protestant | 6 | 4 | |

| Roman catholic | 1 | 5 | |

| Jewish | 1 | 0 | |

| Islamic | 1 | 2 | |

| Other | 1 | 1 | |

| Experience of serious illness in the last five years | Relative or friend diagnosed with serious illness | 13 | 10 |

| Personally diagnosed with serious illness | 0 | 0 | |

| Experience of death and dying in the last five years | Death of relative or friend | 14 | 11 |

| Experience of death and dying | Looked after relative or friend while dying at some point | 10 | 9 |

Table 2.

Condensed Representation of Modified Grounded Theory Findings from Phase One

| English categories | German categories |

|---|---|

| EoLC reflections comprise many different dimensions and processes, including reflections on bereavement. | Emotions and memories are evoked when discussing the existential, difficult, and important topic of EoLC. Age and experience influence thoughts about EoLC. |

| Quality EoLC is expected. EoLC is influenced by context. Social relationships are sustained during the time of care. Autonomy and choice is possible, and information from trusted professionals is wanted. | EoLC involves hopes, uncertainty, and others. Hope for “safe,” skilful, sensitive, and individualized care provided in a human environment. Uncertainty is experienced regarding how, where, and who would provide the care. EoLC care needs sensitivity to individual and family need. |

| Imagined and real preferences regarding preferred place of death may, in reality, differ once EoLC is required. | EoLC preferences regarding place of terminal care, place of death, and other choices may change over time. |

| Priorities and preferences are determined dynamically during EoLC. | During EoLC, an evolving decision-making process regarding preferences and priorities will occur. |

| Serious illness is understood in terms of outcome, the level of influence you have over the illness, and its symptoms and problems. Its impact on your life and relationships, and a concern about being a burden forms part of the understanding of serious illness within the context of EoLC. | Attention to independence, autonomy, and practical matters during EoLC is important. |

| Individual worldviews inform understandings of EoLC, and this is influenced by media's representation of EoLC topics. | The valuing of both quality and quantity of life, along with concern regarding prolonging life unnecessarily forms part of EoLC. |

EoLC, end-of-life care.

Phase one: English results

Multi-dimensional EoLC reflections

Respondents' reflections on EoLC involved many dimensions, including imaginative thinking, introspection, consideration, and time. … when you first started talking I was sitting in front of my e-mails thinking perhaps I can do this at the same time … I realized within minutes that I couldn't possibly do that … Bereavements were thought of, alongside reflections about social relationships and responsibilities to others. … I can remember [a relative] that bought me up … they died … I was away at that time … EoLC discussions were understood as potentially distressing if someone close to you had recently died. … the time after the loss in a sense is almost the more distressing time if you're basically being asked about it.

Quality of EoLC

A high standard of EoLC, delivered in relation to the proximity and anticipation of death, in a contextually relevant manner was expected. … an environment where professionals are helping … in the dying process … helping my partner, children … in a way that people wouldn't be able to do individually and in an environment which is truthfully painless and fits that situation. Autonomy and choice were perceived as possible and desired. … support you and help you cope with it … not … too much treatment that you wouldn't be able … to make choices and things like that … High-quality care should be provided especially as people are dying and not able to be cured. What would be best for me if I was in that situation? Where you feel confident that everything is being done that can be done. Information from trusted professionals was expected. … I assume that whoever I was consulting I would trust in which case I would rather be told about it without my asking … Effort to enable enjoyment, pleasantries, respect and dignity, and to be symptom-free were important. Quality and quantity of life were valued.

Choice, control, and preferred place of death

A sense of choice and control about place of death fluctuated. Respondents shared that sometimes people died in a place that was not their preferred place of death. … having known people that die in hospital and it's kind of not necessarily their choice … it's just that's where they are and that's where it happens … maybe it's out of their control.

Dynamic determination of priorities and preferences

The extent individuals felt they could determine EoLC priorities and preferences before it was needed varied because: all aspects of care were perceived as equal, interrelated, and important; EoLC involved a dynamic process; and until death comes … it is unknown territory. Consideration of one's own and others' needs, along with the implications of each decision would be required. Also, serious illness altered you into a different person, meaning that when EoLC was needed different choices might be made. … there's the sort person I was before—I'd be a different one once I had the prognosis.

Serious illness within the EoLC context

Serious illness within the context of EoLC was understood in terms of: outcome, ranging from death to recovery; the level of influence you have over the illness; and its symptoms and problems. Its impact on your life and relationships also formed part of EoLC understanding, along with a real concern about being a burden to others because of the illness.

Worldview informs understanding of EoLC

Respondents' worldviews informed their understanding of EoLC. This included their views of self and the decision-making process during the time of care, along with their level of willingness to think about death and dying. Media's representation of EoLC also influenced decisions and opinions. … on television people who have cancer and then in the end they say no they're not having any more treatment they're just going to live out their lives … the side effects can be so awful that you think yep I can understand how people do get to that.

Phase one: German results

The existential, difficult, and important topic of EoLC

EoLC was an existential, difficult, and important topic. I find this an important topic that one should talk about … .it always gets repressed … Thinking about it evoked emotions and memories, and thoughts were influenced by age and experience. I have thought about it, honestly said. When I worked in [place of work], I thought about it every day as one day I might become perhaps old. And then one thinks about it and how the care will be.

Hope, uncertainty, and involving others

It was hoped that safe, sensitive, and individualized care provided in a human environment would form part of EoLC. Skilful physical, personal, emotional, social, spiritual, and medical care was expected. Good medical care, secondly good human companionship … .safety in the care … medical, human-psychological care. Uncertainty regarding how, where, and who will provide the care was felt. If capable enough and not overburdened by doing so, family members who were available at the time would provide some of the care. Sensitivity to individual and family needs was required.

Changing preferences regarding place of terminal care and death

Respondents' preferences regarding terminal care and place of death indicated possible change over time depending on their circumstances, proximity to death, and the pressure of the illness. When the disease progresses and one feels the pressure, another way of thinking might come up. Changing perceptions about their own capability and the capability of others in relation to the EoLC situation also formed part of their decision making. The degree of importance placed on preferred place of death varied, ranging from very important to irrelevant. The context of EoLC influenced preferences … palliative care ward means that you will die at any moment. That is bitter, but when you are so exhausted, I believe it [preferred place of death] does not matter anymore. The main thing is that you are well cared for.

Evolving decision-making

In the presence of deteriorating health, respondents indicated an evolving decision-making process related to their anticipated changing circumstances. Maintaining some choice and control in decision making was important, even when it was impossible to predict what decisions might be needed. Autonomous decision making was described as aided through documenting wishes beforehand, receiving information and honest opinions from professionals, and making collaborative decisions with trusted people. Sometimes, decisions may have to be made by others. Otherwise, I would like to choose … .my wife and my children and so on [to make decisions for me].

Attention to independence, autonomy, and practical matters during EoLC

During EoLC, declining health alongside a loss of physical independence and autonomy would occur over a period of many years. EoLC could be going on for years. It is the point in time where it really becomes difficult to participate autonomously in life. Through attention to practical day-to-day matters it is possible to compensate, to a degree, for loss of independence. Attention to and compensation of this loss was important. Who will care for me? How seriously ill will I get? Who will look after my body? That would be very important for me. And then naturally, as I want to die at home, who deals with the household? Who will look after the food, the washing, my children? That would be in my head the first place.

Valuing quality and quantity of life, and concern regarding prolonging life unnecessarily

Within the context of EoLC, serious illness was understood as involving distressing symptoms and functional decline to a point where expert care was necessary. Maintaining quality of life, and letting life end naturally was important. Artificially prolonging life was, at times, rejected. … To keep artificially alive, that is not for me. Being kept alive when there was no chance for recovery was different than being kept alive when there was hope to live life in the future. … the intervention is only then important and right, if medically one can expect that the person wakes from the coma, and somehow can continue with their life. Quality of life and prolonging life were intertwined. I always thought that I might want to prolong my life … perhaps it is more important that I can shape the time more meaningfully with regards to quality of time. Both are important for me.

Phase two: Cross-country synthesis

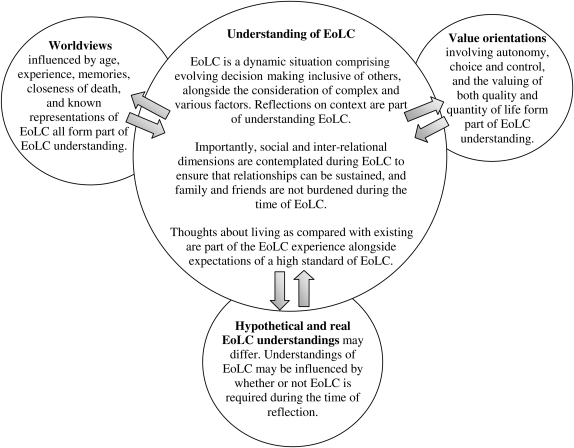

The synthesis from phase two resulted in the identification of four key concepts with underlying coherence. As usual with qualitative synthesis, similarities and difference were synthesized through a repositioning of the primary findings into a new interpretative order (see Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Phase one findings: Synthesised account of English and German country-level understandings.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first cross-national comparison and synthesis of public views regarding EoLC across two European countries. Qualitative analysis identified English and German views, and synthesis enabled a coherent cross-national understanding for these two groups of respondents.

Our first research objective—to identify country-related understandings (phase one)—resulted in similarities and differences in EoLC understandings between the groups. Similarities included EoLC expectations, and a valuing of social and relational dimensions. Expectations of a high standard of EoLC involving autonomy and choice spanned both groups. This aligns with international results from a systematic review regarding prognostication and end-of-life communication.4 Similarly to our findings, discourse analysis findings from English and German palliative care literature also identified a valuing of family inclusion in palliative care from both countries.16 Ambivalence regarding being a burden to others, yet wanting to be with them, has been described as creating tension for patients,17,18 and a systematic review regarding burden and end-of-life care identified burden as concerning for patients in Europe (UK) and beyond (Canada, Japan, Kenyan, Korea, and the United States).19 Continuing to consider sociorelational aspects in future cross-national EoLC research to establish international priority areas for policy and care therefore remains important.

The second research objective—to undertake a cross-country synthesis (phase two)—resulted in a cohesive account of EoLC understanding. This understanding consisted of a dynamic situation comprising evolving decision making inclusive of others. It was contextually related, and required consideration of complex, variable factors amid change. Respondents' value orientations, worldviews, and belief that there may be differences between their real and imagined preferences appeared integral to their EoLC understanding. These dimensions need careful consideration when interpreting the pan-European survey findings, and will be useful when our survey findings become available.

In addition, country-specific differences apparent in the qualitative analysis findings demonstrate the value of retaining country-related diversity alongside multinational synthesized accounts. For example, context in the synthesized account was identified as relevant to EoLC understanding, and for English respondents' context was understood as influencing the service provided, whereas for our German respondents' context was understood as possibly influencing their care preferences. Our novel research design enables stand-alone and comparable country-related findings that are also able to be synthesized.

A key finding that spanned both groups that remained evident within the synthesized account is the evolving EoLC decision-making process. This finding adds to knowledge regarding EoLC decision making by identifying that even though most respondents were able to articulate their EoLC preferences and priorities, when probed further about this they expressed uncertainty about their decisions, and about having to take a forward-thinking approach regarding this matter. To date, the evidence for changing preferences and priorities,18 and uncertainty in decision-making regarding EoLC is small and unclear. It remains unknown whether preferences and priorities are different in hypothetical EoLC scenarios as compared with real scenarios. Future research could involve people with life-limiting illnesses who know they have a limited prognosis in order to compare and contrast the findings from this study. Also, longitudinal research regarding preferences and priorities is required to determine whether change occurs over time, an EoLC decision-making model is needed, and cross-sectional remains important. Qualitative synthesis enables us to anticipate (not predict) what might be involved in analogous situations.10

A number of potential limitations in our research design need to be considered, including positive self-representation, the absence of data triangulation, and convenience sampling.20–23 Research quality was aided through systematic analysis, precisely defined ontology and method, and source-language analysis. Interpretive rigor was aided through our systematic approach alongside a design involving reflexivity, interpretation, and communication.24 Our synthesis remained grounded in the data10 through the use of transcripts and ongoing examination of context.

The majority of our healthy respondents had experienced the diagnosis of a relative/friend with a serious illness and the death of a relative/friend in the last 5 years. Also, most had looked after or supported a close relative/friend while dying. Their understandings may therefore differ from those who have not had these experiences. In addition, our purposive sampling within a convenience sampling frame led to a mostly homogenous ethnic sample. Purposive sampling is recommended for future studies to enable heterogeneity. Nevertheless, how respondents' understandings were shaped by their experiences, relationships, ethnicity, sociocultural context, values, and knowledge of existing services are interesting questions that this study has raised.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that inductive analysis of cognitive interview data can inform EoLC understanding, and that qualitative synthesis of comparable cross-county datasets can lead to conceptually coherent, cross-national outcomes. Our data were optimized through a culturally responsive inductive and interpretive paradigm to illuminate highly subjective and complex phenomena. Although our findings are not generalizable, this is a substantive methodological development regarding EoLC qualitative data synthesis, advancing EoLC survey development across Europe and responding to an urgent need for coordinated research efforts for EoLC in Europe.

Acknowledgments

PRISMA is funded by the European Commission's Seventh Framework Programme (contractnumber: Health-F2-2008-201655) with the overall aim to coordinate high-quality international research into end-of-life cancer care. PRISMA aims to provide evidence and guidance on best practice to ensure that research can measure and improve outcomes for patients and families. PRISMA activities aim to reflect the preferences and cultural diversities of citizens, the clinical priorities of clinicians, and appropriately measure multidimensional outcomes across settings where end–of-life care is delivered. Further information regarding PRISMA resources including PRISMA questionnaires and surveys is available from the corresponding author. Principal Investigator: Richard Harding. Scientific Director: Irene J. Higginson, who is also a senior National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) investigator. Dr. Catherine Evans is also thanked for her useful comments on an earlier version of this article. PRISMA Members: Gwenda Albers, Barbara Antunes, Ana Barros Pinto, Claudia Bausewein, Dorothee Bechinger-English, Hamid Benalia, Emma Bennett, Lucy Bradley, Lucas Ceulemans, Barbara A. Daveson, Luc Deliens, Noël Derycke, Martine de Vlieger, Let Dillen, Julia Downing, Michael Echteld, Natalie Evans, Dagny Faksvåg Haugen, Nancy Gikaara, Barbara Gomes, Marjolein Gysels, Sue Hall, Richard Harding, Irene J Higginson, Stein Kaasa, Jonathan Koffman, Pedro Lopes Ferreira, Johan Menten, Natalia Monteiro Calanzani, Fliss Murtagh, Bregje Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Roeline Pasman, Francesca Pettenati, Robert Pool, Tony Powell, Miel Ribbe, Katrin Sigurdardottir, Steffen Simon, Franco Toscani, Bart van den Eynden, Jenny van der Steen, Paul Vanden Berghe, and Trudie van Iersel.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: Palliative Care: The Solid Facts. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higginson IJ. Sen-Gupta GJA. Place of care in advanced cancer: A qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences. J Palliat Med. 2000;3:287–300. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyashita M. Hashimoto S. Kawa M. Shima Y. Kawagoe H. Hase T. Shinjo Y. Suemasu K. Attitudes toward disease and prognosis disclosure and decision making for terminally ill patients in Japan, based on a nationwide random sampling survey of the general population and medical practitioners. Palliat Support Care. 2006;4:389–398. doi: 10.1017/s1478951506060482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parker SM. Clayton JM. Hancock K. Walder S. Butow PN. Carrick S. Currow D. Ghersi D. Glare P. Hagerty R. Tattersall MH. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: Patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harding R. Higginson IJ. PRISMA: A pan-European co-ordinating action to advance the science in end-of-life cancer care. Euro J Cancer. 2010;46:1493–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beatty PC. Willis GB. Research synthesis: The practice of cognitive interviewing. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2007;71:287–311. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willis B. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murtagh FEM. Addington-Hall JM. Higginson IJ. The value of cognitive interviewing techniques in palliative care research. Palliat Med. 2007;21:87–93. doi: 10.1177/0269216306075367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green J. Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. London: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noblit G. Hare R. Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies. London: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daveson B. O'Callaghan C. Grocke D. Indigenous music therapy theory building through grounded theory research: The developing indigenous theory framework. Arts in Psychotherapy. 2008;35:280–286. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strauss A. Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. London: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strauss A. Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques, Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. London: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pope C. Mays N. Qualitative Research in Healthcare. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Limited; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rice P. Ezzy D. Qualitative Research Methods: A Health Focus. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pastrana T. Junger S. Ostgathe C. Elsner F. Radbruch L. A matter of definition: Key elements identified in a discourse analysis of definitions of palliative care. Palliat Med. 2008;22:222–232. doi: 10.1177/0269216308089803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray MA. O'Connor AM. Fiset V. Viola R. Women's decision-making needs regarding place of care at end of life. J Palliat Care. 2003;19:176–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Townsend J. Frank AO. Fermont D. Dyer S. Karran O. Walgrove A. Piper M. Terminal cancer care and patients preference for place of death: A prospective-study. Br Med J. 1990;301:415–417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6749.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McPherson CJ. Wilson KG. Murray MA. Feeling like a burden to others: A systematic review focusing on the end of life. Palliat Med. 2007;21:115–128. doi: 10.1177/0269216307076345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frankel R. Devers K. Qualitative research: A consumer's guide. Educ Health. 2010;13(1):113–123. doi: 10.1080/135762800110664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holstein J. Gubrium J. Inside Interviewing: New Lenses, New Concerns. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller J. Glassner B. The “inside, the “outside”: Finding realities in interviews. In: Silverman D, editor. Qualitative Research Theory, Method and Practice. 2nd. London: Sage; 2004. pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubin H. Rubin I. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. London: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popay J. Rogers A. Williams G. Rationale and standards for the systematic review of qualitative literature in health services research. Qual Health Res. 1998;8:341–351. doi: 10.1177/104973239800800305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]