Abstract

Background

Chronic cocaine use may lead to premature atherosclerosis, however, the prevalence of and risk factors for coronary artery disease in asymptomatic cocaine users have not been reported.

Methods

Between August 2007 and June 2010, 385 African American chronic cocaine users aged 25 to 54 years were consecutively enrolled in a study to investigate the prevalence of CT angiographically- defined significant (≥50%) coronary stenosis and related risk factors. Sociodemographic, drug-use behavior, medical history and medication data were obtained by interview and confirmed by medical chart review. Clinical examinations were performed as well as extensive laboratory tests including those for fasting lipid profiles, HIV, high sensitivity C-reactive protein, and vitamin D. Contrast-enhanced coronary CT angiography was performed.

Results

Significant coronary stenosis was detected in 52 of 385 participants (13.5%). The prevalences were 12% and 30% in those with low risk and with middle-high risk Framingham score, respectively. In those with low risk scores, the prevalences of significant stenosis were 10% and 18% in those without and with vitamin D deficiency, defined as serum 25-(OH) vitamin D < 10 ng/mL (p=0.08). Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that vitamin D deficiency (adjusted OR=2.18, 95% CI: 1.07–4.43) is independently associated with the presence of significant coronary stenosis after controlling for traditional risk factors.

Conclusions

The study indicates that the prevalence of significant coronary stenoses is high in asymptomatic young and middle-aged African American chronic cocaine users. These findings emphasize the importance of aggressive reduction of risk factors, including vitamin D deficiency in this population.

Keywords: Chronic cocaine use, Significant coronary stenosis, Vitamin D deficiency, CT coronary angiography

Introduction

In 2008, there were 1.9 million current cocaine users aged 12 years or older in the United States, comprising 0.7% of the population [1]. As cocaine abuse continues, the number of cocaine-related cardiovascular events, including acute coronary syndrome, cardiomyopathy, and sudden death from cardiac causes, has increased dramatically [2–4]. With the use of non-invasive coronary imaging, we reported that chronic cocaine use is associated with coronary atherosclerotic plaque in young-to-middle aged, African Americans [5–8] with no symptoms of coronary disease. However, the prevalence of subclinical coronary artery disease in chronic cocaine users has rarely been reported. Since African Americans have a greater risk of vitamin D deficiency and the highest overall coronary artery disease (CAD) mortality rate of any ethnic group in this country [9–11], we conducted this study to investigate the prevalence of traditional and novel risk factors for CAD, in particular vitamin D levels, and their association with significant coronary stenosis, defined as (>50% luminal narrowing as measured by coronary CT angiography), in young and middle-aged African American chronic cocaine users.

Thus, the objectives of this study were (1) to estimate the prevalence of significant coronary stenosis with the use of contrast-enhanced CT coronary angiography in asymptomatic African American chronic cocaine users and (2) to examine the association of traditional risk factors of CAD and some non-traditional risk factors, such as vitamin D deficiency, on the presence of significant coronary stenosis in African American chronic cocaine users.

Subjects and Methods

Study participants

Between August 2007 and June 2010, 385 African American chronic cocaine users were consecutively enrolled in a study to investigate the cardiovascular consequences of HIV infection and cocaine use at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. Interviews and chart review were conducted to obtain sociodemographics, medical history, current medications, and drug-use behaviors. Clinical examinations were performed; lipid profiles, HIV, high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), and vitamin D laboratory tests were obtained; and 64-slice MDCT for coronary CT angiography were performed. Information pertaining to use of cocaine (powered cocaine and crack cocaine) and all other illegal drugs (such as opiates, benzodiazepines, or methamphetamine) was collected, including frequency, forms, administration mode (injection, smoking, etc.), and duration of drug use.

Inclusion criteria were age between 25 and 54 years, chronic cocaine use, and African American race (self-designated). Chronic cocaine use was defined as chronic use of cocaine by any route for at least 6 months, administered at least four times a month. Non-cocaine use was defined as either never used cocaine or not used at least in the past 5 years. Exclusion criteria were (1) infrequent cocaine use (fewer than four times a month, consecutive 6 months), (2) any evidence of ischemic heart disease, (3) any symptoms believed to be related to cardiovascular disease, and (4) pregnancy.

The Committee on Human Research at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine approved the study protocol, and all study participants provided written informed consent. All procedures used in this study were in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Coronary CT angiography

A noncontrast MDCT scan was performed on a Sensation 64 Cardiac Seimens Medical Solutions scanner (Erlangen, Germany) to determine the coronary artery calcium score with a sequential scan of 3-mm slices with prospective ECG triggering, 30 × 0.6-mm detector collimation, and tube current 135 mAs at 120 kV. Subsequently, coronary CT angiography (CTA) was performed on the same equipment using 80 mL of isosmolar contrast agent (320 mg iodine/mL) injected at 4–5 mL/s. Imaging was performed with retrospective ECG-gating, 32 × 0.6-mm detector collimation with flying focal spot to give effective detector collimation of 64 × 0.6 mm, 330 ms gantry rotation, 850 mAs and 120 kV. Subsequently, 0.75-mm-thick axial slices were reconstructed at 0.4-mm intervals with B25 kernel using a half-scan reconstruction algorithm with resulting temporal resolution of 165–185 ms. Ten reconstructions were done through the cardiac cycle at 10% increments in the R-R interval. If needed, patients were medicated with metoprolol prior to the scan to achieve a heart rate <65 beats per minute.

CAC score, volume, and mass were measured on a workstation (Leonardo, Syngo, Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA). Regions of interest were placed over each of the coronary arteries with the threshold for pixels of greater than 130 HU for determining calcified plaque. Coronary vessels were assessed for patency and stenosis using 3D visualization tools after the axial images were reviewed for determination of anatomy, quality of the study, and appearance of the vessels.

One reviewer (E.K.F), blinded to the participants’ risk factor profiles, independently evaluated the contrast-enhanced MDCT scans by examining the axial slices, curved multiplanar reformations, and thin-slab maximum intensity projections. The coronary artery tree was segmented according to the modified American Heart Association classification, and the segments were investigated for plaque and luminal narrowing. The coronary arteries were divided into proximal, mid, and distal segments, with each segment investigated for luminal narrowing. Plaques were classified as calcified or noncalcified, and the degree of stenosis was classified as less than, equal to, or greater than 50% diameter stenosis. Diameter stenosis ≥50% was defined as significant coronary stenosis.

Vitamin D measurement

Sera were collected, centrifuge and stored at −70C until analyzed. Serum 25-OH vitamin D was determined by a direct, competitive chemiluminescence immunoassay (DiaSorin, Stillwater, Minn) [12]. The level of detection for 25-OH vitamin D was < 4 ng/ml. This method accurately measures both D2 and D3 together and is reported as a total 25 (OH) vitamin D. The reference range is 32 –100 ng/ml. This study identifies vitamin D deficiency according to the Framingham Offspring Study that defines vitamin D deficiency as serum 25 (OH) vitamin D < 10 ng/mL.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All continuous parameters were summarized by medians and interquartile ranges, and all categorical parameters were summarized as proportions. To compare between-group differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, lipid profiles, drug-use behaviors, and other factors, the non-parametric Wilcoxon two-sample test was used for continuous variables and the Fisher’s exact test was employed for categorical variables.

The Clopper-Pearson approach was used to calculate 95% exact binomial confidence intervals [13]. Because the number of participants with significant coronary stenosis was relatively small, an exact logistic regression model was used to examine associations between factors and significant coronary stenosis [14].

Univariate logistic regression models were first fitted to evaluate the crude association between the presence of significant coronary stenosis and each of the factors—including age, sex, total serum cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, serum triglycerides, hsCRP, cigarette smoking, alcohol use, glucose level, blood pressure, body mass index, waist-hip ratio, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and cocaine or other illicit drug (opiates, benzodiazepines, methamphetamine) or alcohol use, individually. Those factors that were significant at the p ≤0.10 level in the univariate models were put into the multiple logistic regression models to identify the factors that were independently associated with the presence of significant coronary stenosis. Those variables that ceased to make significant contributions to the models were deleted in a stagewise manner, yielding the final models. The Framingham risk score was calculated to estimate the CAD risk [15]. The p-values reported are two-sided. A p-value <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

General characteristics

The general and clinical characteristics of the study participants, sorted by the presence of significant coronary stenosis, are presented in Table 1. Compared with those who did not have significant coronary stenoses, those with significant coronary stenoses were older (p<0.0001) and more likely to be male (p=0.017), had a higher waist-hip ratio (p=0.015), a higher cholesterol level (p<0.0001), a higher LDL level (p=0.002), a longer duration of cocaine use (p=0.013), and a higher Framingham risk score (FRS) (p<0.0001). Overall, the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was 19.7% (95% CI: 16%–24%). Approximately 29% of those with significant coronary stenosis were vitamin D deficient, whereas 18% of those without significant coronary stenosis were vitamin D deficient (p=0.08).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cocaine-Using Study Participants, by the Presence of Significant Coronary Stenosis*

| Characteristic | Total | Significant Coronary Stenosis | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 385) | No (N = 333) | Yes (N = 52) | ||

| Age (years) | 44 (40–48) | 44 (39–47) | 47 (44–51) | <0.0001 |

| Female (%) | 35.8 | 38.1 | 21.5 | 0.017 |

| Family history of CAD (%) | 22.1 | 20.7 | 30.8 | 0.10 |

| Cocaine use ≥15 y (%) | 48.6 | 48.4 | 50.0 | 0.82 |

| Cigarette smoking (%) | 92.2 | 92.5 | 90.4 | 0.60 |

| Cigarette smoking ≥15 y (%) | 83.4 | 82.9 | 86.5 | 0.51 |

| Alcohol use (%) | 92.2 | 92.8 | 88.5 | 0.28 |

| hsCRP ≥2 mg/dL (%) | 43.2 | 42.2 | 50.0 | 0.82 |

| hsCRP (mg/dL) | 1.6 (0.6–4.3) | 1.5 (0.5–4.1) | 2.0 (0.7–5.2) | 0.16 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 115 (107–125) | 115 (106–125) | 117 (109–124) | 0.64 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 77 (69–82) | 76 (69–82) | 80 (70–85) | 0.14 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 85 (79–92) | 85 (79–92) | 85 (79–91) | 0.70 |

| BMI | 24.9 (22.1–28.1) | 24.9 (22.1–28.1) | 24.8 (21.5–27.8) | 0.50 |

| Waist-hip ratio | 0.88 (0.84–0.92) | 0.87 (0.83–0.92) | 0.90 (0.86–0.93) | 0.015 |

| HIV infection | 40.0 | 39.6 | 42.3 | 0.71 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 168(145–196) | 165 (143–194) | 191 (162–227) | <0.0001 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 91 (73–115) | 89 (71–112) | 107 (84–131) | 0.002 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 53 (42–67) | 53(43–66) | 56 (40–71) | 0.55 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 90 (65–132) | 90 (65–129) | 92 (66–145) | 0.61 |

| Serum 25(OH)D (ng/ml) | 15.0 (10.0–23.0) | 15.0 (11.0–23.0) | 13.5 (9.0–21.5) | 0.23 |

| Vitamin D deficiency | 19.7 | 18.3 | 28.9 | 0.08 |

| Years of cocaine use | 14 (8–20) | 13 (8–19) | 15 (6–20) | 0.013 |

| Framingham risk score | 4 (2–7) | 3 (2–5) | 5 (4–8) | <0.0001 |

| Framingham score ≥10.0 (%) | 9.6 | 7.8 | 21.2 | 0.003 |

Median (interquartile range) for continuous variables, proportion (%) for categorical variables. Abbreviations: HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; hsCRP = high sensitivity C-reactive protein; BP = blood pressure; Glucose = fasting glucose; BMI = body mass index (kg/m2); LDL-C = low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C = high density lipoprotein cholesterol; Serum 25(OH)D = 25-dihydroxyvitamin D; Vitamin D deficiency = serum 25(OH)D <10 ng/mL; Framingham score = Framingham risk score.

According to the FRS algorithm [15], 348 (90.4%) of the 385 participants (219 of the 247 men and 129 of the 138 women) were classified as having a low risk of CAD, i.e., the FRS was <10%.

Prevalence of significant coronary stenosis

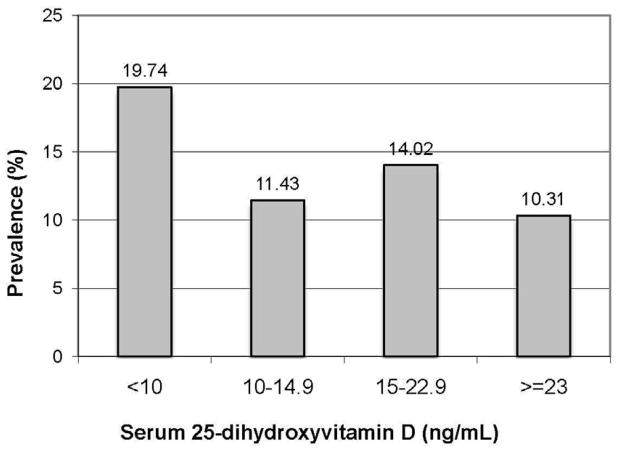

For all study participants, the overall prevalence of the presence of significant coronary stenosis was 13.5% (95% CI: 10.3%–17.3%). The prevalence by quartile of serum 25 (OH) vitamin D is presented in Figure 1. There was a trend suggesting that a lower level of 25 (OH) vitamin D was associated with a higher prevalence of significant coronary stenosis, but the trend was not significant (p=0.21).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Significant Coronary Stenosis, by Quartile of Serum 25-dihydroxyvitamin D. For all study participants, the prevalences were 19.7% (15/76), 11.4% (12/105), 14.0% (15/107), and 10.3% (10/97) in those whose 25-dihydroxyvitamin D was <10 ng/mL, whose 25-dihydroxyvitamin D was between 10 and 14.9 ng/mL, whose 25-dihydroxyvitamin D was between 15 and 22.9 ng/mL, and whose 25-dihydroxyvitamin D was ≥23 ng/mL, respectively (10, 15, and 23 ng/mL were the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of serum 25-dihydroxyvitamin D). For those with low risk according to the Framingham score, the prevalences were 17.9% (12/67), 12.0% (12/100), 9.7% (9/93), and 9.1% (8/88) in those whose 25-dihydroxyvitamin D was <10 ng/mL, whose 25-dihydroxyvitamin D was between 10 and 14.9 ng/mL, whose 25-dihydroxyvitamin D was between 15 and 22.9 ng/mL, and whose 25-dihydroxyvitamin D was ≥23 ng/mL, respectively.

For the low risk study participants, the prevalence of the presence of significant coronary stenosis was 11.8% (95% CI: 8.6%–15.6%). The prevalence by quartile of serum 25 (OH) vitamin D is also presented in Figure 1. There was a trend suggesting that a lower level of 25 (OH) vitamin D was associated with a higher prevalence of significant coronary stenosis, and the trend was marginally significant (p=0.077).

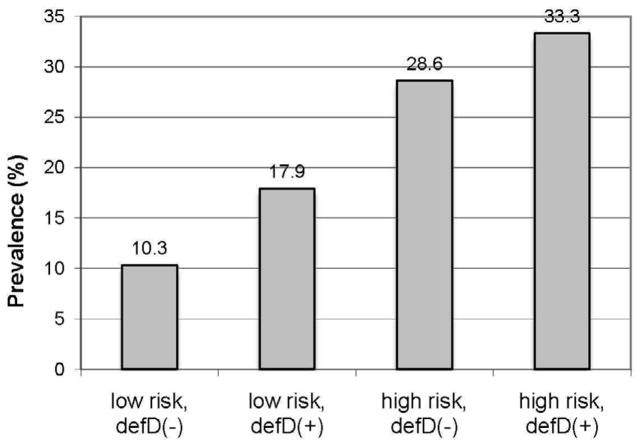

The prevalence by the FRS category and vitamin D deficiency status is presented in Figure 2. The prevalences were 10.3% (29/281) in those with low risk according to the Framingham score and without vitamin D deficiency, 17.9% (12/67) in those with low risk according to the Framingham score and with vitamin D deficiency, 28.6% (8/28) in those with intermediate-high risk according to the Framingham score (≥10%) and without vitamin D deficiency, and 33.3% (3/9) in those with moderate-high risk according to the Framingham score (≥10%) and with vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D deficiency was associated with a higher prevalence of significant coronary stenosis in those with low Framingham risk (p=0.046), but the association between vitamin D deficiency and the presence of significant coronary stenosis in those with moderate-high FRS was not significant (p=1.00).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of Significant Coronary Stenosis, by Framingham Risk Score Category and Vitamin D Deficiency Status. The prevalences were 10.3% (29/281), 17.9% (12/67), 28.6% (8/28), and 33.3% (3/9) in those with low risk according to the Framingham score and without vitamin D deficiency, those with low risk according to the Framingham score and with vitamin D deficiency, those with moderate-high risk according to the Framingham score and without vitamin D deficiency, and those with moderate-high risk according to the Framingham score and with vitamin D deficiency, respectively. Low risk = the Framingham risk score <10, High risk = the Framingham risk score ≥10, defD (−) = without vitamin D deficiency, defD (+) = with vitamin D deficiency.

Factors associated with the presence of significant coronary stenosis

By univariate logistic regression analyses, risk factors associated with the presence of significant coronary stenosis at the p <0.05 level included age ≥45 years, male gender, waist-hip ratio >0.88, total serum cholesterol ≥170 mg/dL, serum LDL-C concentration ≥90 mg/dL, and FRS ≥10. Marginally associated with the presence of significant coronary stenosis (p ≤0.10) were family history of coronary artery disease, diastolic BP ≥80 mm Hg, and vitamin D deficiency.

The final model indicated that the presence of significant stenosis was associated with age ≥45 years (adjusted OR: 2.33, 95% CI: 1.21–4.48), male gender (adjusted OR: 2.53, 95% CI: 1.22–5.25), waist-hip ratio ≥0.88 (adjusted OR: 2.12, 95% CI: 1.12–4.00), total cholesterol concentration ≥170 mg/dL (adjusted OR: 2.43, 95% CI: 1.27–4.62), and vitamin D deficiency (adjusted OR: 2.18, 95% CI: 1.07–4.43) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic, Laboratory, and Clinical Factors in Relation to the Risk of Presence of Significant Coronary Stenosis *

| Variable | Significant Coronary Stenosis | |

|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Age (y) | ||

| <45 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥45 | 2.55 (1.36–4.78) | 2.33 (1.21–4.48) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Male | 2.30 (1.14–4.63) | 2.53 (1.22–5.25) |

| Family history of CAD | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 1.70 (0.89–3.24) | |

| Years of cocaine use | ||

| <15 | 1.00 | |

| ≥15 | 1.07 (0.60–1.92) | |

| Cigarette smoking | ||

| Never | 1.00 | |

| Ever | 0.76 (0.28–2.09) | |

| Years of cigarette smoking | ||

| <15 | 1.00 | |

| ≥15 | 1.33 (0.57–3.09) | |

| Alcohol use | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 0.60 (0.23–1.54) | |

| hsCRP (mg/dL) | ||

| <2 | 1.00 | |

| ≥2 | 1.37 (0.76–2.46) | |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | ||

| <120 | 1.00 | |

| ≥120 | 1.21 (0.67–2.18) | |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | ||

| ≤80 | 1.00 | |

| >80 | 1.73 (0.96–3.11) | |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | ||

| <85 | 1.00 | |

| ≥85 | 1.02 (0.57–1.83) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| <25 | 1.00 | |

| ≥25 | 0.95 (0.53–1.71) | |

| Waist-Hip ratio | ||

| <0.88 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥0.88 | 2.17 (1.18–3.99) | 2.12 (1.12–4.00) |

| HIV infection | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 1.12 (0.62–2.02) | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | ||

| <170 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥170 | 2.48 (1.34–4.61) | 2.43 (1.27–4.62) |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | ||

| <90 | 1.00 | |

| ≥90 | 2.10 (1.13–3.89) | |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | ||

| <50 | 1.00 | |

| ≥50 | 0.91 (0.50–1.65) | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | ||

| <90 | 1.00 | |

| ≥90 | 0.98 (0.55–1.76) | |

| Framingham score | ||

| <10% | 1.00 | |

| ≥10% | 3.16 (1.45–6.87) | |

| Vitamin D deficiency | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.81 (0.93–3.50) | 2.18 (1.07–4.43) |

Abbreviations: HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; hsCRP = high sensitivity C-reactive protein; BP = blood pressure; Glucose = fasting glucose; BMI = body mass index; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Vitamin D deficiency = serum 25(OH)D <10 ng/mL; Framingham score = Framingham risk score.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to estimate the prevalence of significant coronary stenosis in African American chronic cocaine users and to examine whether vitamin D deficiency is associated with significant coronary stenosis in members of this group without symptoms of coronary artery disease. This study demonstrates that the overall prevalence rate of significant coronary stenosis in asymptomatic young-to-middle-aged African American chronic cocaine users was high (13.5%), especially since more than 90% of study participants were classified as low risk by the Framingham risk score.

The high rate of significant coronary stenosis may be partly explained by chronic cocaine use. Animal studies suggest that chronic cocaine use may cause endothelial damage, leading to accelerated development of atherosclerosis [16–18]. Nevertheless, despite the fact that the effects of cocaine in humans have been documented in clinical and autopsy studies [19–23], the prevalence of significant coronary stenosis in cardiovascularly asymptomatic African American chronic cocaine users has not been reported.

African Americans have the highest age-adjusted prevalence of CAD and CAD mortality rate of any ethnic group in this country [24–28]. The etiologies of CAD in African Americans remain unclear. Compared with other racial groups, African Americans may have fewer abnormal markers for subclinical disease (for example, on average, African Americans may have a lower coronary calcium score than do Caucasians), but appear to have an equal or greater total burden of coronary atherosclerosis [29]. They tend to have a significantly lower prevalence of calcific deposits that is independent of CAD risk factors [29,30] or the extent of atherosclerosis than do other racial groups [31–33]. It is possible that the higher rate of manifestations of CAD in this group is because atherosclerotic plaques in African Americans are more susceptible to rupture than are plaques in non-African American individuals [34].

In addition to chronic cocaine use and African American race (not having compared African Americans to other races, this study itself does not suggest African American race is a contributory factor), this study suggests that vitamin D deficiency may be a contributory factor in the presence of significant coronary stenosis. Since exposure to UV-B rays is the primary determinant of vitamin D status in humans, and since deep skin pigmentation in African Americans makes vitamin D photosynthesis inefficient [35], vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in African Americans [36]. This study shows that while the prevalence of significant coronary stenosis in those with a low FRS and without vitamin D deficiency was 10%, the prevalence in those with a low risk score and vitamin D deficiency was 18%, almost twice as high. Furthermore, with the use of logistic regression analysis, this study demonstrates the vitamin D deficiency was independently associated with the presence of significant coronary stenosis after controlling for age, sex, waist-hip ratio, and serum cholesterol.

A growing body of evidence suggests that vitamin D deficiency may be associated with cardiovascular disease. For example, the Framingham Offspring Study, which included 1739 study participants without prior cardiovascular disease, reported that vitamin D deficiency (defined as 25[OH] vitamin D <10 ng/ml) was associated with an increased risk for developing a first cardiovascular event after 5 years of follow-up as compared with subjects with 25(OH) vitamin D levels >15 ng/ml (hazard ratio: 1.80, 95% CI: 1.05–3.08) [37]. A large cross-sectional study using the NHANES databases found that in a sample of 16,603 men and women aged ≥18 years, those with 25(OH) vitamin D levels <20 ng/mL had an increased risk of prevalent CAD (adjusted OR: 1.20, 95% CI: 1.01–1.36) [38].

Although vitamin D inhibits various markers of inflammation that are associated with intimal and medial calcification [39], the biological mechanisms by which vitamin D deficiency may accelerate the development and progression of coronary heart disease are not fully understood. Over the past decade inflammation has been identified as a critical component in cardiovascular pathology [40]. Furthermore, increasing evidence supports the involvement of inflammation in the varies stages of the atherosclerotic process [41]. Inflammatory markers such as, CRP and IL-6 have been associated with increasing CVD, atherosclerosis and myocardial infraction [42–43]. In fact, IL-6 is a marker for significant coronary stenosis in cardiovasularly asymptomatic individuals [44].

This study has several limitations. First, because all of the study participants were African Americans and were not a random sample of all people with chronic cocaine use, the results should be interpreted with caution. Second, since the majority of participants were smokers, the effects of cigarette smoking on the prevalence of significant stenosis could not be evaluated, both individually and combined. Third, the sample size of this study was relatively small due to limited resources. Fourth, due to the nature of the cross-sectional design, some hidden confounding factors, such as socioeconomic status were not adjusted for. Furthermore, since this study was performed in African Americans living in inner-city Baltimore, where cocaine use is often intertwined with other drug addictions, the effects of these drugs (or multiple-drug interactions) on CAD could not be completely controlled for by statistical analyses. Fifth, although non-invasive CTA is an excellent diagnostic tool for demonstrating atherosclerotic burden, 10% to 14% of coronary arterial segments are not visualized by CTA [45]. Nevertheless, recent studies have reported excellent diagnostic accuracy for 64-slice MDCT in the detection of significant stenosis in smaller coronary artery segments and side branches (sensitivity of 86% to 94%; specificity of 93% to 97%) [46–49].

Despite its limitations, this study’s findings of an unexpectedly high rate of silent coronary artery disease in asymptomatic African American chronic cocaine users have disturbing but important implications for the early prevention of CAD and management of clinically silent CAD in this population. The study strongly suggests that for African American chronic cocaine users, an aggressive reduction of traditional CAD risk factors, including lowering cholesterol and maintaining optimal body weight, is particularly important. Since vitamin D deficiency imposes a significantly increased risk of coronary stenoses in a population identified by Framingham as low risk, future studies evaluating the impact of vitamin D measurement and appropriate supplementation in those with low levels are warranted. However, since there have been only a few clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of vitamin D supplementation and the beneficial effects of vitamin D supplementation derived from these trials were not consistent, better-designed trials with adequate doses of vitamin D supplementation are warranted [39]. Finally, a trial conducted in African American chronic cocaine users is urgently needed.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health (NIH R01DA 12777, DA15020, and DA25524).

We thank the study participants for their contributions. The study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health (NIH R01DA 12777, DA15020, and DA25524). The authors of this manuscript have certified that they comply with the Principles of Ethical Publishing in the International Journal of Cardiology [50].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2009. Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lange RA, Hillis LD. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine use. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:351–358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benzaquen BS, Cohen V, Eisenberg MJ. Effects of cocaine on the coronary arteries. Am Heart J. 2001;142:402–410. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.117607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bamberg F, Schlett CL, Truong QA, Rogers IS, Koenig W, Nagurney JT, et al. Presence and extent of coronary artery disease by cardiac computed tomography and risk for acute coronary syndrome in cocaine users among patients with chest pain. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:620–625. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai S, Lai H, Meng Q, Tong W, Vlahov D, Celentano D, et al. Effect of cocaine use on coronary calcification among black adults in Baltimore. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:326–328. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02475-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai S, Lima JAC, Lai H, Vlahov D, Celentano D, Tong W, et al. HIV-1 Infection, cocaine, and coronary calcification. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:690–695. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.6.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai S, Fishman EK, Lai H, Moore R, Cofrancesco J, Pannu H, et al. Long-term cocaine use and antiretroviral therapy are associated with silent coronary artery disease in cardiovascularly asymptomatic African Americans with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:600–610. doi: 10.1086/526782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai S, Bartlett J, Lai H, Moore R, Cofrancesco J, Pannu H, et al. Long-term combination antiretroviral therapy is associated with the risk of coronary plaques in African Americans with HIV infection. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23:815–824. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nesby-O’Dell S, Scanlon KS, Cogswell ME, Gillespie C, Hollis BW, Looker AC, et al. Hypovitaminosis D prevalence and determinants among African American and white women of reproductive age: third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:187–192. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanley DA, Davison KS. Vitamin D insufficiency in North America. J Nutr. 2005;135:332–337. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferdinand KC. Coronary heart disease and lipid-modifying treatment in African American patients. Am Heart J. 2004;147:774–782. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ersfeld DL, Rao DS, Body JJ, Sackrison JL, Jr, Miller AB, Parikh N, et al. Analytical and clinical validation of the 25(OH) vitamin D assay for the Liaison automated analyzer. Clin Biochem. 2004;37:867–874. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clopper C, Pearson S. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26:404–413. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirji KF, Mehta CR, Patel NR. Computing distributions for exact logistic regression. JASA. 1987;82:1110–1117. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson PWF, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kloner RA, Hale S, Alker K, Rezkalla S. The effects of acute and chronic cocaine use on the heart. Circulation. 1992;85:407–419. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.2.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trulson ME, Epps LR, Joe JC. Cocaine: Long-term administration depletes cardiac cellular enzymes in the rat. Acta Anat. 1987;129:165–168. doi: 10.1159/000146394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maillet M, Chiarasini D, Nahas G. Myocardial damage induced by cocaine administration of a week’s duration in the rat. Adv Biosci. 1991;80:187–197. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isner JM, Estes M, Thompson PD, Costanzo-Nordin MR, Subramanian R, Miller G, et al. Acute cardiac events temporally related to cocaine abuse. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1438–1443. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612043152302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cregler LL, Mark H. Relation of acute myocardial infarction to cocaine abuse. Am J Cardiol. 1985;56:794. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)91140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isner JM, Chokshi SK. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine. Curr Probl Cardiol. 1991;64:94–123. doi: 10.1016/0146-2806(91)90013-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathias DW. Cocaine-associated myocardial ischemia: review of clinical and angiographic findings. Am J Med. 1986;81:675–678. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gradman AH. Cardiac effects of cocaine: a review. Yale J Biol Med. 1988;61:137–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Heart Association. 2002 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. American Heart Association; Dallas, TX: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Report of the Working Group on Research in Coronary Heart Disease in Blacks. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health DHHS; 1994. pp. 1–94. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillum RF, Mussolino ME, Madans JH. Coronary heart disease incidence and survival in African-American women and men. The NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:111–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-2-199707150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark LT, Ferdinand KC, Flack JM, Gavin JR, 3rd, Hall WD, Kumanyika SK, et al. Coronary heart disease in African Americans. Heart Dis. 2001;3:97–108. doi: 10.1097/00132580-200103000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111:1233–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orakzai SH, Orakzai RH, Nasir K, Santos RD, Edmundowicz D, Budoff MJ, et al. Subclinical coronary atherosclerosis: racial profiling is necessary! Amer Heart J. 2006;152:819–827. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang W, Detrano RC, Brezden OS, Georgiou D, French WJ, Wong ND, et al. Racial differences in coronary calcium prevalence among high risk adults. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:1088–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80735-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eggen DA, Strong JP, McGill HC., Jr Coronary calcification: relationship to clinically significant coronary lesions and race, sex, and topographic distribution. Circulation. 1965;32:948–955. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.32.6.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strong JP, McGill HC. The natural history of aortic atherosclerosis: relationship to race, sex and coronary lesions in New Orleans. Exp Mol Pathol. 1963;52(suppl I):15–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blache JO, Handler FP. Coronary artery disease: a comparison of the rates and patterns of development of coronary arteriosclerosis in the negro and white races with its relation to clinical coronary artery disease. Arch Pathol. 1950;50:189–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doherty TM, Detrano RC, Mautner SL, Mautner GC, Shavelle RM. Coronary calcium: the good, the bad, and the uncertain. Am Heart J. 1999;137:806–814. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rostand SG. Vitamin D, blood pressure, and African Americans: toward a unifying hypothesis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1697–1703. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02960410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ginde AA, Liu MC, Camargo CA., Jr Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988–2004. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang TJ, Pencina MJ, Booth SL, Jacques PF, Ingelsson E, Lanier K, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;117:503–511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kendrick J, Targher G, Smits G, Chonchol M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D deficiency is independently associated with cardiovascular disease in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verhave G, Siegert CE. Role of vitamin D in cardiovascular disease. Neth J Med. 2010;68:113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ikonomidis I, Stamatelopoulos K, Lekakis J, Vamvakou GD, Kremastinos DT. Inflammatory and non-invasive vascular markers: The multimarker approach for risk stratification in coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2008;199:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Volpato S, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Balfour J, Chaves P, Fried LP, et al. Cardiovascular disease, interleukin-6, and risk of mortality in older women: the women’s health and aging study. Circulation. 2001;103:947–953. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH. Plasma concentration of interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation. 2000;101:1767–1772. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.15.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai S, Fishman EK, Lai H, Pannu H, Detrick B. Serum IL-6 Levels are Associated with Significant Coronary Stenosis in Cardiovascularly Asymptomatic Inner-City Black Adults in the US. Inflamm Res. 2009;58:15–21. doi: 10.1007/s00011-008-8150-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pannu HK, Jacobs JE, Lai S, Fishman EK. Coronary CT angiography with 64-MDCT: assessment of vessel visibility. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:119–126. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raff GL, Gallagher MJ, O’Neill WW, Goldstein JA. Diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive coronary angiography using 64-slice spiral computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:552–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leber AW, Knez A, von Ziegler F, Becker A, Nikolaou K, Paul S, et al. Quantification of obstructive and nonobstructive coronary lesions by 64-slice computed tomography: a comparative study with quantitative coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leschka S, Alkadhi H, Plass A, Desbiolles L, Grünenfelder J, Marincek B, et al. Accuracy of MSCT coronary angiography with 64-slice technology: first experience. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1482–1487. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mollet NR, Cademartiri F, van Mieghem CA, Runza G, McFadden EP, Baks T, et al. High-resolution spiral computed tomography coronary angiography in patients referred for diagnostic conventional coronary angiography. Circulation. 2005;112:2318–2323. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.533471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shewan LG, Coats AJ. Ethics in the authorship and publishing of scientific articles. Int J Cardiol. 2010;144:1–2. [Google Scholar]