Abstract

Significant scale-up of donors’ investments in health systems strengthening (HSS), and the increased application of harmonization mechanisms for jointly channelling donor resources in countries, necessitate the development of a common framework for tracking donors’ HSS expenditures. Such a framework would make it possible to comparatively analyse donors’ contributions to strengthening specific aspects of countries’ health systems in multi-donor-supported HSS environments. Four pre-requisite factors are required for developing such a framework: (i) harmonization of conceptual and operational understanding of what constitutes HSS; (ii) development of a common set of criteria to define health expenditures as contributors to HSS; (iii) development of a common HSS classification system; and (iv) harmonization of HSS programmatic and financial data to allow for inter-agency comparative analyses. Building on the analysis of these aspects, the paper proposes a framework for tracking donors’ investments in HSS, as a departure point for further discussions aimed at developing a commonly agreed approach. Comparative analysis of financial allocations by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and the GAVI Alliance for HSS, as an illustrative example of applying the proposed framework in practice, is also presented.

Keywords: Health systems strengthening, classification, investment analysis

KEY MESSAGES.

Availability of a common framework for tracking donor investments in health systems strengthening (HSS) would make it possible to comparatively analyze donors’ contributions to strengthening specific aspects of countries’ health systems in multi-donor-supported HSS environments.

Four pre-requisite factors required for developing such analytical framework are: (i) harmonization of conceptual and operational understanding of what constitutes HSS; (ii) development of a common set of criteria to define health expenditures as contributors to HSS; (iii) development of a common HSS classification; and (iv) availability of comparably structured HSS financial and programmatic data across funding entities.

The paper proposes an analytical framework for tracking donor investments in HSS, as a departure point for further discussions.

Introduction

Recent studies (Coker et al. 2004; Barker et al. 2007; Tkatchenko-Schmidt et al. 2010) have found health systems strengthening (HSS) to be key for the successful scale-up of disease control interventions. Additional evidence (Travis et al. 2004) also suggests that weak health systems are one of the main bottlenecks in achieving the health Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Consequently, the last decade saw HSS leaping to the top of the global health agenda. Significantly increased focus on HSS creates a strong impetus for global health partners to better co-ordinate their actions, and results in the increased application of various mechanisms for harmonizing donors’ HSS support to countries. This in turn necessitates the development of a common framework for comparatively tracking donors’ contributions to HSS in countries’ multi-donor environments. Arguably, such a framework would bring the following practical benefits:

Estimate each donor’s contributions to strengthening specific components of countries’ health systems;

Allow donors to comparatively analyse their HSS investments at the country, regional and global levels;

Estimate the amount of donors’ HSS investments against the global need in HSS support for reaching health MDGs as defined by the High Level Task Force on Innovative International Financing for Health Systems (HLTF 2009).

A gap to fill: towards a common analytical framework for HSS investments

Presently the most prevalent approach to analysing resources invested in countries’ health sector is the National Health Accounting (NHA), which is designed to track investments in disease control, service delivery, public health and other areas of the health system. However, NHA does not provide comparative evidence to monitor individual donors’ allocations to strengthening specific aspects of countries’ health systems. Furthermore, NHA is primarily a health policy tool for countries, designed to inform the health policy dialogue, development, implementation, monitoring and evaluation (WHO 2003). As such, NHA’s usability as an accounting tool for donors, to analyse their HSS expenditures at the agency level, is limited. Therefore, development of a common framework, building on the NHA principles, but designed for tracking donors’ HSS investments has a practical value. This paper suggests that addressing the following four issues is necessary for developing a common framework for tracking donors’ HSS investments:

Harmonization of conceptual and operational understanding of what constitutes health systems strengthening: despite a wealth of literature on health system objectives and their functional and organizational arrangements, there is a lack of common understanding of what constitutes health systems strengthening (Reich 2008). HSS was recently described as a ‘new buzzword, in danger of becoming a container concept that is used to label very different interventions’ (Marchal 2009). In order to comparatively track donors’ HSS investments, it is essential to harmonize, across all health actors, the understanding of what health systems strengthening means, both as a concept and as an operation.

Agreement on the criteria for identifying expenditures that contribute to HSS: health actors should reach an agreement on a set of criteria to determine which types of health interventions and their expenditures may be considered to contribute to strengthening health systems. For example, consensus on investments made in strengthening technical capacity of the Ministry of Health as contributing to HSS would be easier to reach than on investments made in strengthening health workers’ capacity in, for example, administering TB DOTS. Despite the fact that both investments are aimed at strengthening health human resources, which represents one of the six ‘building blocks’ of the health system (WHO 2007), for some, the latter investment may not qualify as HSS due to the argument that such investments contribute to control of a single disease, not to strengthening broader health systems. Therefore, a common approach is needed on where to draw boundaries between HSS and non-HSS interventions.

Developing an agreed classification of health system strengthening: a common HSS classification is needed for aggregating HSS activities and their expenditures in order to comparatively estimate the amount of investments allocated for strengthening specific components of the health system by various sources.

Harmonizing the usage of HSS programmatic and financial data: inter-agency harmonization of HSS data is necessary as only comparably structured data would allow for systematic, comparative analyses across donor agencies.

Keeping these shortfalls in mind, this paper explores the feasibility of developing a common analytical framework for HSS investments. Each of the above four areas is explored below as a departure point for further discussions. Results of approved HSS funding by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria’s (GF) and the GAVI Alliance are also presented as a practical illustration of applying the proposed framework in practice.

Conceptual considerations for designing an HSS resource tracking framework

Review of the technical literature reveals a proliferation of multiple approaches to thinking about health systems (Marchal 2009). A range of health systems conceptual frameworks have been proposed, which offer diverse perspectives in terms of focus, scope, taxonomy, linguistics, usability and other features (Box 1).

Box 1 An illustrative list of health systems frameworks.

Performance framework (WHO 2000)

Building blocks framework (WHO 2007)

Reforms framework (Roberts et al. 2003)

Systems framework (Atun 2008)

Primary health care framework (WHO 2008)

Each of these frameworks provides a unique view of the health system. The Performance Framework explores the functioning of the health system and explains its main objectives. The Building Blocks Framework provides a useful categorization of health systems elements into several ‘blocks’, which portray the system as a blending of various structural, organizational and institutional components. The Reforms Framework clarifies a complex range of processes affecting these components and explores the policy instruments (the ‘control knobs’) to influence them. The Systems Framework focuses on ‘critical health system functions’ and on the multi-faceted interactions among them. The Primary Healthcare Framework provides an in-depth analysis of a sub-level, arguing that primary care represents the centrepiece of the health system and that policies generated at this level may influence the entire system and beyond. As suggested by Shakarishvili et al. (2010), despite being diverse in the scope and in approaches taken to explain the health system, these frameworks are complementary in that they offer mutually enriching views. By building on synergies among them a converged framework can be developed for common use. For developing a practical approach to tracking HSS investments, it is important to build on analysis of the health systems frameworks in order to harmonize conceptual and operational understanding of health systems strengthening. Brief discussion below is allocated for outlining those synergistic aspects of the health systems frameworks, which are relevant for arriving to a common understanding of HSS.

First, among the health systems frameworks reviewed, there seems to be an overall consensus, with some differences in definitions used, around the following goals of the health system: (i) improved health status, (ii) protection against health-related financial risk, (iii) responsiveness to needs, and (iv) satisfaction of consumers’ expectations. While these are the overall goals of the health system and as such should be reflected in countries’ national health strategies, HSS strategies, being an integral part of national health strategies, often address more specific objectives, fulfilment of which cumulatively contributes to achieving the broader health system goals. HSS objectives are context-specific and should be prioritized through robust situational analysis. A few illustrative examples of HSS objectives may include: strengthening the capacity of the service delivery system for effective scale-up of coverage, reforming the health financing system to increase equitable access to care, developing the health information system to enhance disease surveillance, etc. Some HSS activities may be disease-specific, while others may cut across several categorical programmes.

Secondly, distinction should be made between activities/investments contributing to health systems strengthening vs. those contributing to improving health outcomes. Building on the notion that the health system is a platform for all inputs and processes producing health, it is easy to consider all activities that contribute to improving health outcomes in HSS. However, in the context of resource tracking, it is more appropriate to speak of HSS as pertaining to the activities that make changes to the health system leading to achieving health system goals, including improved outcomes, and not as about all actions that contribute to improving health outcomes. For example, investments made in treating patients with antiretrovirals contribute to improving health outcomes, but do not necessarily strengthen the health system.

Thirdly, distinction should also be made between operational and conceptual constituents of health systems strengthening. While both are necessary for strengthening the health system, it is the operational constituents that carry monetary value, and ultimately determine the level of financial investments in HSS. Conceptual constituents, since they have no monetary value as investments, despite their importance for health systems strengthening, are uninteresting for resource tracking purposes. For example, to track a donor agency’s investments in HSS, namely in strengthening health human resources, it is important to know how much the donor invests in health workforce training (training, an operational constituent of HSS). However, for assessing the overall effectiveness of strengthening the health workforce, one would also need to know whether, for example, the health workers have been distributed equitably throughout the country regions (equity, a conceptual constituent of HSS). But, since the level of equity applied to trainees’ distribution is not measured in monetary terms as an expenditure, this constituent is not interesting for resource tracking purposes, even though equity is indeed an integral part of HSS. Having said that, if the donor also invests in improving the equity of the health system, for example by supporting relevant policy development and implementation, then these activities, carrying monetary value, would count as contributors to HSS, as operational constituents contributing to improving the ‘governance and policy’ component of the health system. In other words, for resource tracking purposes, it is necessary to differentiate between HSS expenditures and HSS itself. The latter is a combination of operational and conceptual constituents, where only the operational constituents incur monetary value and as such are interesting for HSS resource tracking, while the conceptual constituents are expenditure-free, and even though they are necessary elements of HSS, they are not included in resource tracking analysis.

While the above discussion helps with unpacking HSS as a concept and as an operation, additional agreement is necessary for harmonizing an approach to distinguishing which interventions made to the health system are HSS and which are not. Therefore, it is useful to develop a set of commonly agreed criteria, by which donors’ programmatic expenditures can be determined as those contributing to HSS. While an agreement on setting such criteria is a subject of further discussions, an illustrative list of the criteria applied to the analysis presented in this paper is provided in Box 2.

Box 2 Inclusion/exclusion criteria for health systems strengthening (HSS) expenditures.

1 Expenditures contributing to strengthening components and elements (see below) of the health system and contributing to health outcomes within only one disease or one thematic area (e.g. HIV, TB, malaria, immunization, reproductive health …) are disease–specific HSS and should be counted as HSS investments (e.g. training nurses in administering TB DOTS, providing cold-chain for immunization etc.);

2 Expenditures contributing to strengthening components and elements (see below) of the health system and contributing to health outcomes across more than one disease- or thematic areas, are cross-cutting HSS and should be counted as HSS investments (e.g. developing a primary care infrastructure, building health workers capacity in integrated management of childhood diseases (IMCI) etc.);

3 Expenditures contributing to strengthening components and elements (see below) of the health system, which are not linked to any specific disease- or thematic area, but encompass broader, sector-wide or multi-sectoral areas are sectoral-HSS and should be counted as HSS investments (e.g. strengthening policy-making capacity of the MoH, developing social health insurance system etc.);

4 Expenditures contributing to improving health outcomes across either one, or several disease- or thematic area(s), but not contributing to strengthening specific components and elements of the health system (see below), are not HSS and should not be considered HSS investments (e.g. clinical service provision, stigma reduction, social support etc.);

5 Expenditures on medicines and other consumables are not HSS, however interventions for strengthening support systems for their provision are (e.g. development of procurement regulations, development of supply-chain management system);

6 Activities contributing to program management (e.g. proposal writing, reporting, administrative costs, overhead) are not HSS;

A classification of HSS interventions

As mentioned above, in addition to harmonizing the understanding of HSS and reaching agreement on a set of inclusion/exclusion criteria for HSS expenditures, in order to develop a common HSS resource-tracking framework it is also necessary to develop an agreed HSS classification. Through this the investments defined as HSS can be aggregated to determine the level of investments allocated for strengthening specific components of the health system. This paper proposes an HSS classification informed by the analysis of multiple health systems conceptual frameworks, and by the review of countries’ perceptions of HSS as reflected in over 80 country HSS funding applications submitted to donor agencies.

Given that the health systems conceptual frameworks contain a certain degree of terminological ambiguities, the proposed classification uses a term ‘health system component’ as the basis of its structure, to describe the concepts, which in various frameworks are labelled differently (e.g. ‘building blocks’, ‘functions’, ‘processes’). The classification is composed of four health system components: ‘health services’, ‘stewardship and governance’, ‘financing system’ and ‘monitoring and evaluation (M&E)/health information system’, each representing a blend of health systems building blocks, functions and processes. For example, the ‘health services’ component can be a ‘building block’ if it is looked at as a combination of facilities, people and equipment. It could also be a ‘health system function’ if it is looked at as an interface or a platform producing health. Or, it could be a ‘process’, describing various actions taking place either at the facility level (e.g. patient care, organizational management, facility maintenance), or at the more macro level, for example, as a referral system. In the context of resource tracking, the four ‘components’ are identified as the eventual targets of HSS interventions for improving health systems performance.

While the classification is informed by the health systems frameworks, the way it organizes the health system does not directly follow any of the frameworks based on which it has been developed. For example, human resources for health (HRH) is presented as a separate ‘building block’ in the WHO framework; however HRH is not identified as a separate health system component in the proposed classification. This is to demonstrate that investments in strengthening HRH, such as capacity building, salaries and others, are embedded under all health system components. Therefore, the classification considers HRH a cross-cutting area, instead of a separate, stand-alone component. Having said this, the classification still allows for separately tracking investments in strengthening HRH, as presented in the results section of the paper. Similarly, another ‘building block’, medical products and technologies, has been included under the service delivery component instead of being a separate component in itself. The reason is that the classification does not regard pharmaceuticals and other consumables as contributors to strengthening health systems, but instead views the development of procurement and supply chain management systems as HSS. As they contribute to strengthening operational support systems of service delivery, these activities have been included under the service delivery component.

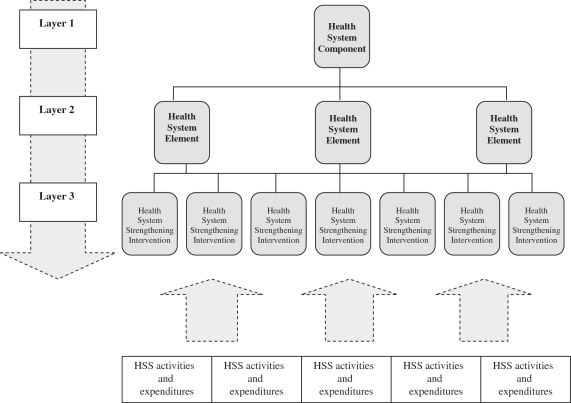

Each of the above four components of the HSS classification is a composite entity. For example, ‘health services’ encompasses staff, infrastructure, organizational management systems, referral systems, demand generation and other expenditures. Therefore, for more detailed analysis of HSS expenditures, the structure of the classification system has been disaggregated by applying consistent rules. The first rule is to disaggregate each of the four health system components into several health system elements, so that each element represents either an action necessary for producing the corresponding component (these are processes, for example policy dialogue, undertaking a survey etc.), or a material, technical, institutional or structural constituent of the corresponding component (these are inputs, for example money, equipment, facility etc.). The second rule is to further disaggregate each health system element into HSS interventions. In the classification system this third layer represents a transitional level from health systems to health systems strengthening. Thus, by knowing the amount of expenditures spent for the activities which compose relevant HSS interventions, it is possible to contextually allocate these expenditures to the relevant health system element, and consequently aggregate them to the level of health system components. Such aggregation would easily allow for comparative cross-donor analysis as by applying the same analytical approaches, it will be possible to attribute each specific donor’s financial contributions to strengthening each element and component of the health system in a given country (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of the proposed health system strengthening (HSS) classification

The proposed HSS classification, informed by the review of over 4400 activities included in 87 country HSS funding applications, and used for undertaking the analysis of HSS investments presented in this paper, is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Health systems strengthening (HSS) classification

| Health system component | Health system element | Health system strengthening intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Health services | Staff | Capacity building in health services |

| Salaries, benefits and non-financial incentives | ||

| Infrastructure | Facility construction, rehabilitation, maintenance | |

| Provision of equipment, hardware, software, furniture | ||

| Operational support systems for health services | Developing organizational management systems | |

| Developing supply chain management and procurement | ||

| Developing quality assurance systems | ||

| Increasing demand for services | ||

| Developing referral systems | ||

| Stewardship and governance | Macro-organization, policies and regulations | Salaries, benefits and non-financial incentives |

| Capacity building | ||

| Co-ordination, management and supervision of policy-making and execution | ||

| Developing support systems (facilities, equipment…) | ||

| Planning, research and priority setting | Survey, research and analysis for policy development | |

| Developing tools and methods for policy-planning and policy-making | ||

| Financing system | Financial planning, resource generation, fund pooling | Development, implementation and monitoring of health financing legislation, policies and regulations |

| Operationalizing health financing system | ||

| Providers' reimbursement system | Developing providers' reimbursement system | |

| Strengthening organizational arrangements for providers' reimbursement system | ||

| Monitoring & evaluation (M&E)/health information system (HIS) | Data collection, analysis and reporting | Developing data collection, analysis and reporting systems |

| Implementing data collection, analysis, research, reporting and dissemination | ||

| Capacity building | ||

| Staff (salary, benefits…) | ||

| Strengthening country M&E system | Strengthening operational support systems for M&E/HIS | |

| Developing disease surveillance system | ||

| Staff (salary, benefits…) | ||

| Capacity building |

Over 4400 activities included in 87 HSS proposals

Harmonizing the usage of HSS data for valid cross-donor comparative analysis

As a recent assessment of the Global Fund’s, World Bank’s and GAVI’s practices of analyzing HSS investments revealed, the three donors not only use different methodological approaches, but they also use different types of data for the analysis (Global Fund et al. 2009). Therefore, for valid inter-agency comparative analysis, it is important to not only harmonize methodologies, but also to standardize the usage of the budgeted (approved), the reimbursed (transferred to the implementing partner) or the actual (spent in the field) expenditure data, since only comparable data would allow for systematic, comparative analyses across funding entities.

Practical application of the HSS resource-tracking framework

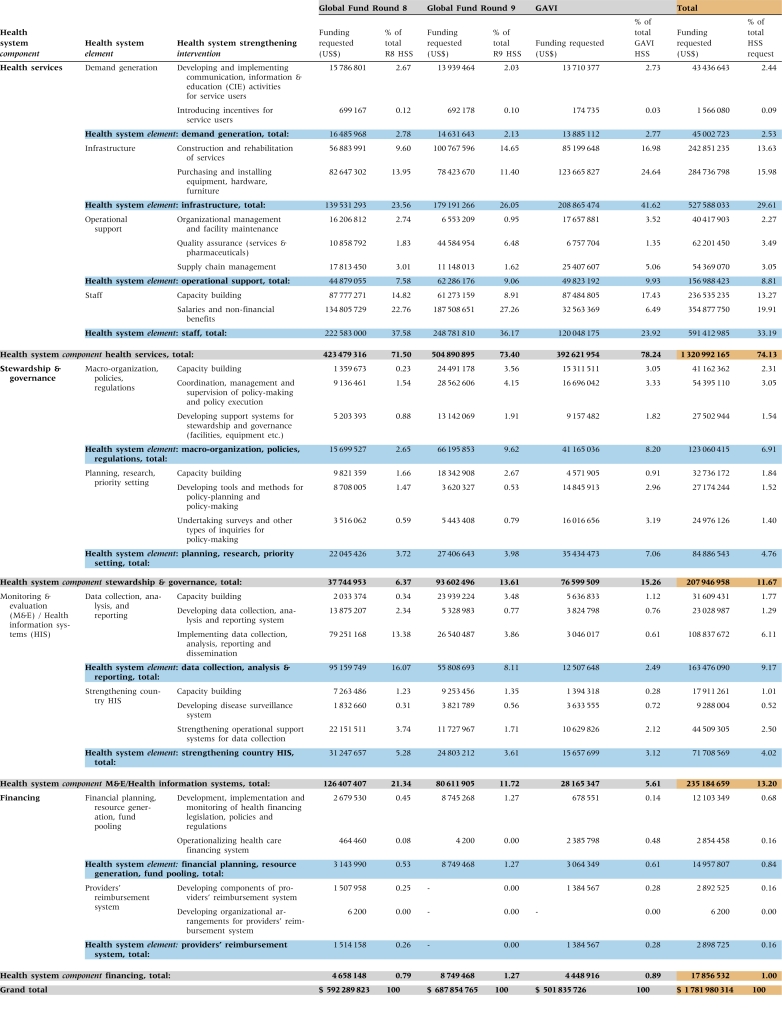

The proposed framework was applied to analyse over 4400 activities and their expenditures included in 87 country HSS proposals approved for funding by the Global Fund in Rounds 8 and 9 (R8 and R9), and by the GAVI Alliance since 2006. The total value of all proposals was US$1.86 billion. However, US$78.8 million was allocated for programme management activities, and therefore, according to the proposed set of HSS inclusion criteria, was not considered HSS-related expenditures. Presentation of the analyses therefore uses US$1.78 billion as the denominator. The study limitation is that the HSS data have been extracted from funding proposals, not from grant reports, which would have included the data on the actual disbursements, instead of the budgeted amounts. The reason is the incompleteness of the data in some country reports. Thus, the analysis reflects countries’ demand for HSS investments, rather than the actual HSS investments. Furthermore, due to time limitations, only the approved GF and GAVI proposals, not all proposals, were analysed; therefore, the analysis reflects a fraction of the total demand. A few illustrative examples of interpreting the data analysis are provided below.

Funding allocations by health system components

Of the four health system components, the vast majority of funding demand fell within the Health Service component. The distribution pattern was consistent across the GF and GAVI, with the only difference being a smaller proportion of funding requested for strengthening the stewardship and governance component by GF sources as opposed to GAVI, with an associated reciprocity for strengthening the M&E/health information system component (Table 2).

Table 2.

Funding request distribution for strengthening health system components

| Health system components | Global Fund R8/R9 (as % of total HSS funding request) | GAVI (as % of total HSS funding request) | Global Fund/GAVI average (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health services | 72.5 | 78.2 | 75.3 |

| Stewardship & governance | 10.3 | 15.3 | 12.8 |

| M&E/health information system | 16.2 | 5.6 | 10.9 |

| Financing | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Grand total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Analysis by health system elements and HSS interventions

The largest contributors to the total funding demand were mainly elements within the health services component. Within this component, over 60% of funding was allocated for the infrastructure development and staff development elements, while the demand generation for services element received only a negligible proportion of total funding. It must be noted that a slight inconsistency across the funding sources were also identified: GAVI’s allocations for the infrastructure development element were higher than that of the GF (41%, GAVI, vs. 23% GF R8 and 26% GF R9), while GF allocated more funding that GAVI for the staff development element (37% GF R8, 36% GF R9, 23.9% GAVI).

The utility of a common classification system is best seen by more in-depth analysis of a single component across funding sources (i.e. GF vs. GAVI). This allows quick comparison of the distribution of funding across HS elements within a given component. Within the health services component, for example, distribution of funding between GF and GAVI were similar, with GAVI providing slightly more resources to infrastructure-related investments (∼53% vs. ∼34%) while the GF supported more staff-related investments (∼50% vs. 30%). Disaggregating further, more details of the funding pattern can be identified: for example, the GF’s funding for staff development is directed more towards the HSS interventions aimed at increasing staff salaries and benefits than towards the interventions for staff capacity building. GAVI, on the other hand, allocates about twice the funding for purchasing and installing equipment, hardware and furniture, compared with construction and rehabilitation of facilities. A complete breakdown of financial allocations for all health system components, elements, and HSS interventions by each of the three funding sources is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Breakdown costs of all health system strengthening (HSS) activities by HSS interventions, health system elements and health system components

|

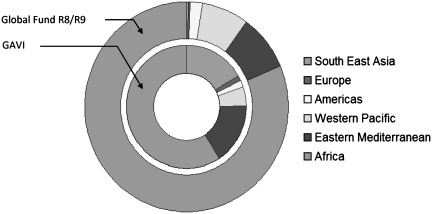

Geographic analysis

On a geographic basis, the analysis revealed significant variation in regional allocations of HSS investments, and slight inconsistency between the GF and GAVI proposals. Proposals originating from countries in the African region generated the bulk of HSS funding demand for both donors (81.3% for the GF, and 59.3% for GAVI). The second largest demand for GF HSS funding originated in the Eastern Mediterranean region (8.65%), while for GAVI it came from South-East Asia (16.79%). Figure 2 below shows a comparative breakdown of GF-GAVI HSS allocations by geographic regions.

Figure 2.

Regional distribution of health system strengthening funding requests

Country-specific analysis

Comparisons of funding can also be done on a country by country basis, allowing assessment of areas of overlapping or complementary funding at the country level. For illustrative purposes some funding patterns are compared for Afghanistan and Burkina Faso. The majority of funding in Afghanistan was for the health services and the M&E/information systems components, and the number of HSS interventions which were funded by both GAVI and the GF were minimal, with only staff-related capacity building receiving investments of comparable size from both sources. Analysis of the Burkina Faso funding showed the opposite picture. Both GAVI and the GF funded large investments in health services and M&E/information systems, but with the exception of only a few HSS interventions, most received comparable funding from both GAVI and GF sources. Such a pattern may suggest that opportunities exist for closer inter-agency coordination at the country level to avoid programmatic and funding overlaps across the donor agencies.

Analysis of human resources for health (HRH) funding

As mentioned earlier, the classification system does not separate HRH as a stand-alone component of the health system. Rather, it classifies HRH-related activities under its various components as a cross-cutting HSS input. However, the classification system still allows for mapping resources allocated for strengthening HRH, both in absolute numbers, and as a share of total HSS investments. In order to perform such analyses, costs of all HRH-related interventions included under various components are added up. Results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Funding for strengthening human resources for health (HRH)

| Health system component | Health system element | HRH-related interventions | HRH investments based on the 24 R8 Proposals (US$) | Sub-total (US$) | Total (US$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health services | Staff | Capacity building | 236.53 million | ||

| 33.09% of total | |||||

| 591.41 million | |||||

| Salaries, financial and non-financial benefits | 354.88 million | 82.73% of total | |||

| 49.64% of total | |||||

| M&E/health information | Data collection, analysis and reporting | Capacity building | 31.61 million | 714.83 million (out of which 591.41 million or 82.73% represents salaries, financial and non-financial benefit support to service providers) | |

| 4.42% of total | |||||

| 49.52 million | |||||

| Strengthening country M&E/health information systems | Capacity building | 17.91 million | 6.93% of total | ||

| 2.51% of total | |||||

| Stewardship & governance | Macro-organization, policies and regulations | 41.16 million | |||

| 5.76% of total | |||||

| 73.90 million | |||||

| Planning, research, priority setting | 32.74 million | 10.34% of total | |||

| 4.58% of total | |||||

| Finance | Capacity building contributing to strengthening the finance component are accounted for under stewardship & governance | ||||

As shown in the table, the total approved funding for HRH including all sources is US$714.83 million, or ∼40% of the total HSS funding request. This is not in addition to the resources allocated for the four HS components; rather this amount is distributed throughout these components. Additionally, the analysis also reveals that GF proposals allocated far more resources to salaries and non-financial benefits for service providers compared with GAVI proposals.

Conclusions

The accelerated move towards harmonizing donor funding to more efficiently support countries’ HSS efforts necessitates the development of a common analytical framework for tracking HSS investments. While health partners have yet to agree on a common approach, this paper proposes a framework for HSS resource tracking as a departure point for further discussions. The four factors suggested as necessary pre-requisites for developing such a common framework—harmonization of conceptual and operational understanding of HSS, agreement on inclusion/exclusion criteria for HSS expenditures, development of a common HSS classification system, and harmonization of HSS programmatic and financial data across donor agencies—are explored, and suggestions on developing various elements of the framework are proposed. The paper also applies the proposed framework to analyzing GF and GAVI HSS programmatic and financial data, demonstrating the practical usability of the approach for producing a wide range of analytical findings. By classifying each HSS activity included in the programme proposals, and their costs, it has been possible to determine the level of financial contributions made by each funding source to strengthening each specific health system element and health system component. If an international consensus on the pre-requisite factors can be reached, it will be possible to standardize the proposed framework for common use, allowing various donors to track their HSS investments for valid and consistent cross-donor comparisons.

Funding

None declared.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Atun R, De Jongh T, Secci K, et al. Integration of targeted health interventions into health systems: a conceptual framework for analysis. Health Policy and Planning. 2009;24:1–8. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker PM, McCannon CJ, Mehta N, et al. Strategies for the scale-up of antiretroviral therapy in South Africa through health system optimization. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;196:457–63. doi: 10.1086/521110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman P. 2009. Unpacking health systems strengthening. Paper presented at the Inter-Agency Technical Workshop on HSS. Washington, DC July 2009. Unpublished document. [Google Scholar]

- Coker R, Atun R, McKee M. Health care system frailties and public health control of communicable disease on the European Union’s new Eastern border. The Lancet. 2004;363:1389–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Fund, GAVI Alliance, World Bank. 2009. Mapping resources for health systems strengthening: current situation and future challenges. Paper presented at the Inter-Agency Technical Workshop on HSS. Washington, DC July 2009. Unpublished document. [Google Scholar]

- International Health Partnership. New York: International Health Partnership (IHP+); 2008. High Level Taskforce on Innovative International Financing for Health Systems: terms of reference and management arrangements. Online at: http://www.internationalhealthpartnership.net/pdf/IHP%20Update%2013/Taskforce/TF%20REVISED%20Press%20statement%20(2008%2011%2030)%20v%206.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Madden R, Sykes C, Ustun T, et al. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. World health organization family of international classifications: definition, scope and purpose. [Google Scholar]

- Marchal B, Cavalli A, Kegels G. Global health actors claim to support health system strengthening: is this reality or rhetoric? PLoS medicine. 2009;6:e1000059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich M, Takemi K, Roberts M, et al. Global action on health systems: a proposal for the Toyako G8 summit. The Lancet. 2008;371:865–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich M, Takemi K. G8 and strengthening of health systems: follow-up to the Toyako summit. The Lancet. 2009;373:508–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61899-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M, Hsiao W, Berman P, et al. Getting Health Reform Right: A Guide to Improving Performance and Equity. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shakarishvili G, Atun R, Berman P, et al. Converging health systems frameworks: towards a concepts-to-actions roadmap for health systems strengthening in low- and middle-income countries. Global Health Governance. 2010;IV(1) [Google Scholar]

- Tkatchenko-Schmidt E, Atun R, Wall M, et al. Why do health systems matter? Exploring links between health systems and HIV response: a case study from Russia. Health Policy and Planning. 2010;25:1–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis P, Bennett S, Haines A, et al. Overcoming health-systems constraints to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. The Lancet. 2004;364:900–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16987-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Health Report 2000 – Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Guide to Producing National Health Accounts. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Everybody’s Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO’s Framework for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Health Report 2008: Primary Health Care, Now More Than Ever. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]