Abstract

Purpose

Although adrenal insufficiency can be managed with steroid replacement, transplantation of adrenocortical cells may represent a more definitive therapy.

Methods

An adrenal failure model was created by adding stress to mice that underwent staged bilateral adrenalectomy. Murine adrenocortical cells were seeded onto collagen sponges. The grafts were implanted under the renal capsule during the first adrenalectomy. Some mice had an additional graft placed next to the kidney. A contralateral adrenalectomy and a laparotomy were performed one week after the first adrenalectomy. Two weeks later, blood was collected for costicosterone measurement, and implants were retrieved for adrenal-specific mRNA analysis and histology. Mice that underwent the same procedures but received a graft without cells served as controls.

Results

Control group mortality was 100%. Mice that had only one cell-seeded implant had 42% survival, whereas mice that had two cell-seeded implants had 100% survival. Retrieved implants demonstrated viable cells and expression of adrenocortical genes. The plasma corticosterone concentration of survived animals was similar to that in normal mice.

Conclusion

Cells transplantation restored the adrenocortical function in these mice. Further optimization of this technique could bring a curative therapy to patients with adrenal insufficiency.

Keywords: adrenocortical cell transplantation, adrenal failure, murine model, adrenalectomy

Introduction

Adrenal insufficiency may arise from primary or secondary causes.1-3 Although adrenal insufficiency is rare, it can become life threatening when overlooked.4 Currently the treatment for this disease involves optimized glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoids replacement.1, 5 Because the physiological demands for steroids vary throughout the day, such treatment is not ideal.5

The feasibility of adrenal transplantation has been demonstrated previously.6-9 Scheumann et al. demonstrated that rats that underwent bilateral adrenalectomy with adrenocortical cell transplantation had higher survival rate. In addition, it was demonstrated that these rats had viable adrenocortical cells and measurable levels of corticosterone.6 Previous studies have also demonstrated the presence progenitor cells within the adrenal cortex, which may contribute to the success of transplantation of adrenocortical cells.10 We previously showed that adrenocortical cells implanted in mice continued to express adrenal-specific genes for up to 8 weeks.5, 11 In this report, we sought to determine whether the implanted adrenocortical cells could support the function of the adrenal glands in mice. Adrenal cells harvested from adult mice were seeded onto a collagen sponge and were implanted into mice that underwent either simultaneous or staged bilateral adrenalectomy. The adrenal-specific genes expressed by the implanted cells and the corticosterone levels were determined in the recipient mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Reagents and Media

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and Ham's F12 medium (DMEM/F12), Knockout DMEM, Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS), fetal bovine serum, horse serum, KO serum replacement, glutamax and antibiotics were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Collagenase I, deoxyribonuclease I, and bovine serum albumin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corp (St. Louis, MO). Collagen sponge Helistat was purchased from Integra LifeSciences (Plainsboro, NY). Adrenal Media was prepared with DMEM/F12 medium, 15% horse serum, 2.5% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. KO Media was prepared with Knockout DMEM, 15% KO serum replacement, glutamax and antibiotics.

2.2 Animals

The use of the animals was approved by the UCLA Animal Research Committee (IRB 2003-178). Female C57/BL6 mice, 8 weeks in age (20-22 g), were purchased from Charles River Laboratory (Wilmington, MA). All animals were maintained in an animal barrier as a non-breeding colony in a temperature and light controlled room, and mice were allowed free access to food and water. In each experiment, C57/BL6 mice served as donors and recipients.

2.3 Isolation of Adrenal Cells and Scaffold preparation

Adrenal glands were procured from mice after euthanasia. After removing the surrounding fat, they were incubated in the digestion mixture at 37°C for 1 hour with gentle shaking.11 The digestion mixture consisted of 10 mL of HBSS containing 2 mg/mL collagenase I, 0.05 mg/mL DNase I, and 5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin. After dispersing the cells through a pipette, they were washed with Adrenal Media and were filtered through a 70-μm strainer (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Cells collected from one adrenal gland (about one million cells) were suspended with KO Media and seeded onto a collagen sponge and incubated for 1 hour prior to implantation.

2.4 Implantation

Mice were divided into 7 groups (Table 1). Animals underwent surgery under general anesthesia. Anesthetic was induced with inhalation of 4.5% Isoflurane and 1L/min oxygen, and anesthesia was maintained with 1.5% Isoflurane and 0.8 L/min oxygen. Animals were observed for 14 days after the last surgery and were euthanized for blood and implant collection.

Table 1.

List of treatment groups.

| Surgery | Cell Implantation | |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | bilateral adrenalectomy | 1 million |

| Group 2 | bilateral adrenalectomy | 0 |

| Group 3 | bilateral adrenalectomy+laparotomy | 1 million |

| Group 4 | bilateral adrenalectomy+laparotomy | 0 |

| Group 5 | staged adrenalectomy+laparotomy | 1 million |

| Group 6 | staged adrenalectomy+laparotomy | 0 |

| Group 7 | staged adrenalectomy+laparotomy | 1 million × 2 |

2.4.1 Group 1

Mice (n=16) underwent simultaneous bilateral adrenalectomy and implantation of one million cells seeded on a collagen sponge. A dorsal midline skin incision was made, followed by muscle incisions parallel to inferior border of liver and spleen. Adrenal glands' vascular pedicles were clamped for 5 seconds before adrenalectomy. The collagen sponge with cells was inserted underneath the kidney capsule on the left side. Muscular layers were sutured with 3-0 Vicryl and the skin with 4-0 Nylon. Total procedure time was approximately 10 minutes.

2.4.2 Group 2

Mice (n=27) underwent simultaneous bilateral adrenalectomy and implantation of a blank collagen sponge under the left renal capsule.

2.4.3 Group 3

Mice (n=4) underwent simultaneous bilateral adrenalectomy and implantation of one million cells seeded on a collagen sponge under the left renal capsule. These mice also underwent a laparotomy by making an abdominal incision from xiphoid process to pubis, and the abdominal contents were manipulated for 5 minutes to extend the procedure to 20 min.

2.4.4 Group 4

Mice (n=4) underwent simultaneous bilateral adrenalectomy and implantation of a blank collagen sponge, followed by an abdominal incision as described in Group 3.

2.4.5 Group 5

Mice (n=12) underwent staged bilateral adrenalectomy with cell implantation. A skin incision was made on a paravertebral line of the left side followed by muscle incision parallel to inferior border of the spleen. The left adrenal gland's vascular pedicle was clamped for 5 seconds before adrenalectomy. The collagen sponge was inserted underneath the left kidney capsule. One week later mice underwent second adrenalectomy. A skin incision was made on a paravertebral line of the right side followed by muscle incision parallel to inferior border of the liver. The right adrenal gland's vascular pedicle was clamped for 5 seconds before adrenalectomy. This was followed by a laparotomy as described in Group 3.

2.4.6 Group 6

Mice (n=12) underwent staged bilateral adrenalectomy as described for Group 5, except a blank sponge was inserted during the first surgery.

2.4.7 Group 7

Mice (n=16) underwent staged bilateral adrenalectomy as described for Group 5, except two cell-seeded sponges were implanted. During the first surgery, the first cell-seeded sponge was inserted underneath the left kidney capsule, and a second cell-seeded sponge was inserted in the perirenal adipose tissue.

2.5 RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

RNA extraction from retrieved implants was performed with Qiagen RNeasy mini kit.12 The expression of specific mRNAs was obtained with quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), Qiagen qRT-PCR kit. Primers and probes for amplifying adrenal genes steroidogenic factor 1 (Sf1), 11-β hydroxylase (Cyp11b1), and aldosterone synthase (Cyp11b2), as well as housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA). Gene expression results of the retrieved tissue were normalized to that of the adrenal gland, which was set to 1 for the purpose of comparison.

2.6 Histology

Implanted collagen sponges underneath the kidney capsule and perirenal tissue were retrieved from Group 7 for histology. The specimens were fixed in formalin, and paraffin-embedded sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

2.7 Corticosterone

Normal mice and mice in Group 7 were euthanized, and blood was collected for corticosterone measurement. Levels were measured using Rat Stress Hormone Panel Kit, Milliplex, #RSH69K. Milipore Corporation (Billerica, MA).

2.8 Statistics

Survival curves were analyzed with Kaplan-Meier estimator, and Student's t-test was used to compare corticosterone levels.

3. Results

3.1 Survival

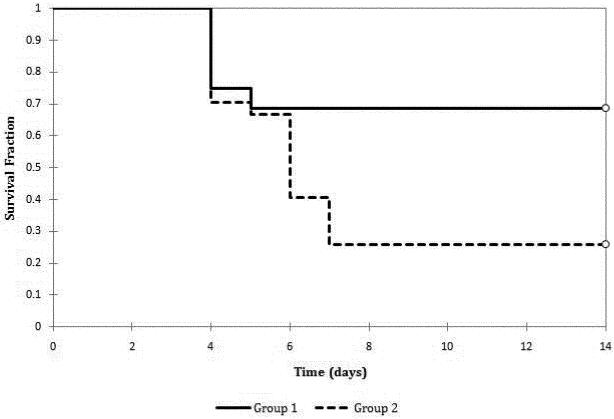

Mice that underwent simultaneous bilateral adrenalectomy and adrenal cell implantation (Group 1) had 69% survival after 14 days, whereas mice that underwent simultaneous bilateral adrenalectomy without cell implantation (Group 2) had 30% survival after 14 days (p=0.024) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Survival of mice that underwent simultaneous bilateral adrenalectomy and cell implantation (Group 1) versus those that underwent simultaneous bilateral adrenalectomy and implantation of a blank sponge (Group 2), p = 0.024.

Although the addition of cell implantation conferred a survival advantage to mice in Group 1, the survival of some mice in Group 2 suggested the presence of accessory adrenal tissues that supported these mice after bilateral adrenalectomy. Similar observations were made by others as well.13-17 Therefore, we created a new animal model to exert more stress to the mice after bilateral adrenalectomy. Mice underwent simultaneous bilateral adrenalectomy and laparotomy in Group 3 (with adrenal cell implantation) and in Group 4 (without cell implantation). Both groups had 100% mortality within 8 days of surgery. This new animal model appears to cause sufficient stress to overcome the function of the accessory adrenal tissues. However, the implanted cells were unable to reverse the adrenal failure in this new model.

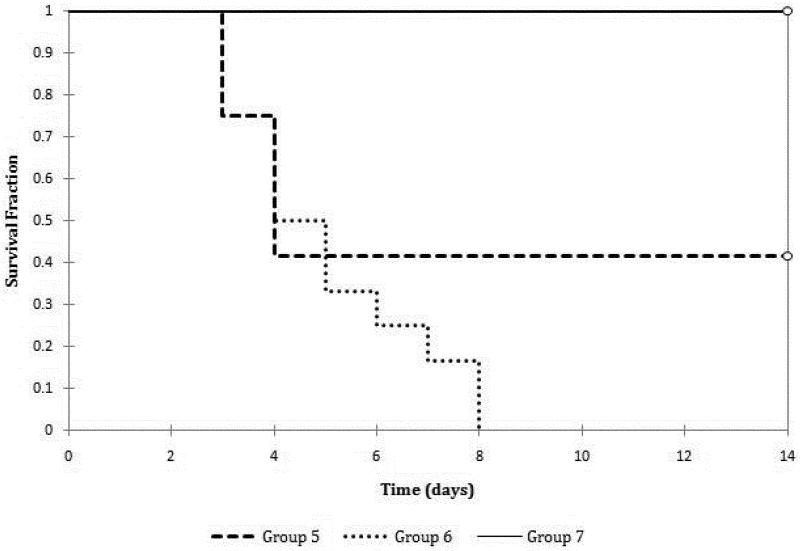

We hypothesized that the implanted cells may need more time to engraft before they can provide adequate function for the mice in this new model. Therefore, we performed staged adrenalectomy (Groups 5 and 6) where the cells were implanted at the first adrenalectomy, followed by a second adrenalectomy and a laparotomy one week later. All mice in Group 6 without cell implantation died within 8 days of the second adrenalectomy, whereas 42% of mice in Group 5 with cell implantation survived 14 days after the second adrenalectomy (p=0.11). To improve the survival further, we increased the number of cells implanted in Group 7. All of these mice survived 14 days after the second adrenalectomy and laparotomy (Figure 2, Group 5 vs. Group 7, p=0.0005, Group 6 vs. Group 7, p=0.0001).

Figure 2.

Survival of mice that underwent staged bilateral adrenalectomy and cell implantation (Group 5) versus those that underwent staged bilateral adrenalectomy and implantation of a blank sponge (Group 6), p = 0.11. Comparison between mice in Group 6 and mice that underwent staged bilateral adrenalectomy and double cell implantation (Group 7), p = 0.0001.

3.2 Corticosterone

The plasma level of corticosterone in mice from Group 7 was 190 ± 33 ng/mL, whereas the plasma level of corticosterone in normal mice was 240 ± 140 ng/mL (p=0.46). Blood was not collected from the other groups in this study.

3.3 Histology

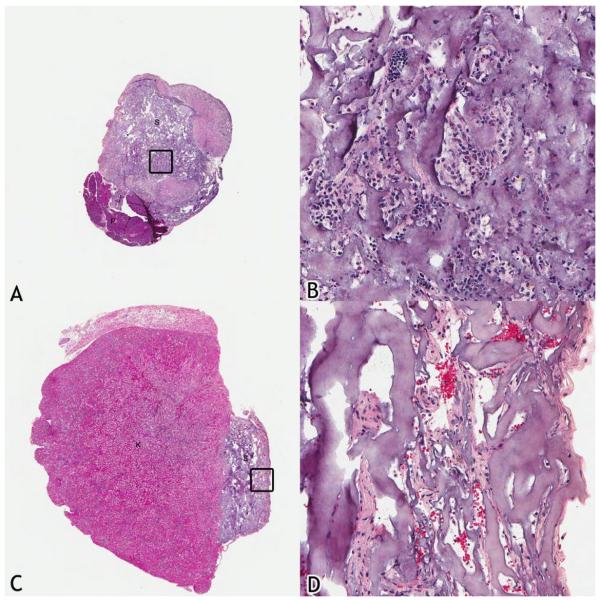

From the retrieved implants under the renal capsule and around the perirenal fat in Group 7, viable cells were observed 3 weeks after transplantation (Figure 3). No distinct glandular formation was observed.

Figure 3.

Histology of the retrieved specimens from Group 7 after 3 weeks of implantation. (A) and (B): Cell-seeded sponge implanted underneath the kidney capsule. (B) is magnification of the inset in (A). (C) and (D): Cell-seeded sponge implanted in the perirenal adipose tissue. (D) is magnification of the inset in (C). S:sponge, P:pancreas, K:kidney.

3.4 RNA Analysis

The retrieved specimens after 3 weeks of implantation expressed adrenal-specific genes. As compared to the native adrenal gland, which was set to be 1, the expressions of Sf1, Cyp11b1 and Cyp11b2 in the retrieved implants were 0.28 ± 0.18, 0.02 ± 0.02, and 0.25 ± 0.33, respectively.

4. Discussion

In this study, we showed that adrenal cell transplantation conferred survival advantage in mice that underwent bilateral adrenalectomy. The technique of adrenal cell transplantation in mice was described previously;5,11 however, it had not been demonstrated that these cells could restore the adrenal function. In addition to improved survival, mice that received a sufficient dose of adrenal cells also had near normal levels of corticosterone 14 days after staged bilateral adrenalectomy. Whether the corticosterone level could be maintained beyond 14 days was not determined in this study. Mineralocorticoid levels were not measured in these mice, but the retrieved tissues did express aldosterone synthase, Cyp11b2.

We also confirmed the previous observation that mice possessed accessory adrenal tissues, and the accessory tissue could support the mice following simultaneous bilateral adrenalectomy. About one quarter of the mice that underwent simultaneous bilateral adrenalectomy survived for more than one month following surgery. Although mice that received cell transplantation had a better survival in this animal model, we sought to create a new animal model to evaluate the function of the implanted cells. To add additional stress, we performed a laparotomy at the time of the second adrenalectomy. The additional stress served to overcome the ability of the accessory adrenal tissue to support the animals' increased demand for steroids. As a result, all animals in Group 3 and 4 died. Although this resulted in a model where adrenal failure led to death, it appeared that the implanted adrenal cells were not able to support the adrenal function. Hypothesizing that the implanted cells might need a period of adaptation before they could function well, we developed to a staged bilateral adrenalectomy model to give the implanted cells more time to engraft before removing the second adrenal gland. The results showed that 42% of animals with cell implantation survived in this new model of adrenal failure, and none of the control animals without cell implantation survived. Furthermore, we showed that when twice the adrenal cells were implanted in Group 7, all mice survived. In addition to the improved survival rates, other data also supported the hypothesis that the cell implantation was able to reverse adrenal failure. Plasma corticosterone levels were restored to levels similar to those in normal mice, and histological analyses demonstrated the presence of viable cells after 3 weeks of implantation. Although we were not able to show glandular formation in the implants, we did confirm the expression of adrenal-specific genes in the retrieved implants.

In conclusion, we developed a new model of adrenal insufficiency and showed that adrenal cell transplantation could reverse the adrenal insufficiency created in this model. We did not administer exogenous steroid in this model because it is known that steroid replacement could also reverse adrenal failure. In this study, the survival of mice that underwent staged bilateral adrenalectomy was dependent on the dose of implanted adrenal cells, which suggest that the transplanted cells were function in vivo. Further optimization of this technique could bring an alternative therapy to patients with adrenal insufficiency.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the Fubon Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (K08-DK068207).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Arlt W, Allolio B. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet. 2003 May 31;361(9372):1881–1893. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oelkers W. Adrenal insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 1996 Oct 17;335(16):1206–1212. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610173351607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oelkers W, Diederich S, Bahr V. Therapeutic strategies in adrenal insufficiency. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2001 Apr;62(2):212–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witt CL. Adrenal insufficiency in the term and preterm neonate. Neonatal Netw. 1999 Aug;18(5):21–28. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.18.5.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn JC, Chu Y, Lam MM, Wu BM, Atkinson JB, McCabe ER. Adrenal cortical cell transplantation. J Pediatr Surg. 2004 Dec;39(12):1856–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheumann GF, Hiller WF, Schroder S, Schurmeyer T, Klempnauer J, Dralle H. Adrenal cortex transplantation after bilateral total adrenalectomy in the rat. Henry Ford Hosp Med J. 1989;37(3-4):154–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas M, Hawks CL, Hornsby PJ. Adrenocortical cell transplantation in scid mice: the role of the host animals' adrenal glands. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003 Jun;85(2-5):285–290. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas M, Hornsby PJ. Transplantation of primary bovine adrenocortical cells into scid mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999 Jul 20;153(1-2):125–136. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanase T, Gondo S, Okabe T, et al. Differentiation and regeneration of adrenal tissues: An initial step toward regeneration therapy for steroid insufficiency. Endocr J. 2006 Aug;53(4):449–459. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.kr-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim AC, Hammer GD. Adrenocortical cells with stem/progenitor cell properties: recent advances. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007 Feb;265-266:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn JC, Chu Y, Qin HH, Zupekan T. Transplantation of adrenal cortical progenitor cells enriched by Nile red. J Surg Res. 2009 Oct;156(2):317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu Y, Wu BM, McCabe ER, Dunn JC. Serum-free cultures of murine adrenal cortical cells. J Pediatr Surg. 2006 Dec;41(12):2008–2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slominski A, Ermak G, Mihm M. ACTH receptor, CYP11A1, CYP17 and CYP21A2 genes are expressed in skin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996 Jul;81(7):2746–2749. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.7.8675607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Droms KA, Fernandez CA, Thaete LG, Malkinson AM. Effects of adrenalectomy and corticosterone administration on mouse lung tumor susceptibility and histogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988 May 4;80(5):365–369. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mueller M, Atanasov A, Cima I, Corazza N, Schoonjans K, Brunner T. Differential regulation of glucocorticoid synthesis in murine intestinal epithelial versus adrenocortical cell lines. Endocrinology. 2007 Mar;148(3):1445–1453. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beuschlein F, Fassnacht M, Klink A, Allolio B, Reincke M. ACTH-receptor expression, regulation and role in adrenocortial tumor formation. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001 Mar;144(3):199–206. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1440199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shigematsu K, Toriyama K, Kawai K, Takahara O. Ectopic adrenal tissue in the thorax: a case report with in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical studies. Pathol Res Pract. 2007;203(7):543–548. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]