to the editor: A novel, general concept of a coupled-clock pacemaker cell system of surface membrane electrogenic proteins that function as a voltage oscillator (M clock) and of intracellular proteins that effect diastolic submembrane Ca2+ oscillations (Ca2+ clock) has been recently put forth (5). The essence of the “yin-yang”-type dynamic coupling of the clocks is based on, in part, several lines of robust experimental data. First, an abrupt disabling of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger function by “spritzing” Na+ free medium during diastolic depolarization (DD) acutely retards the normal DD sinoatrial node cells (SANCs) (1, 10). Second, for sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ load transitions, after removal of voltage clamp at the maximum diastolic potential that depletes SR Ca2+ load, the beat-to-beat reduction in cycle length is predicted by the beat-to-beat growth of local submembrane Ca2+ releases (LCRs) that activate an inward Na+/Ca2+ exchanger current during DD (11). Third, stochastic beat-to-beat variations in LCR emergence during DD within a given SANC predict the cell's intrinsic cycle length variability (7). Both Ca2+ release and sarcolemmal ion channels are involved in mechanisms of intrinsic beating variability in cardiac cell cultures (8). Fourth, for the existence of Ca2+ clock, rhythmic LCRs persist under voltage clamp and in chemically skinned SANCs when cell Ca2+ is sustained.

In the January 2011 issue of the American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, Himeno et al. (3) report patch-clamp experiments and numerical modeling in guinea pig SANCs that seem to refute the coupled-clock hypothesis. But some issues, not considered by the authors, might be important for the interpretation of their results.

Result 1

The spontaneous action potential (AP) rate changed little when BAPTA, a Ca2+ chelator, was acutely infused via a patch pipette into SANCs.

Our interpretation.

The unexpected BAPTA effect, however, can be explained on the basis of a small, artifactual patch seal leak current, a well-recognized artifact in whole cell patch-clamp experiments that occurs when the membrane patch is ruptured. The occurrence of such leak currents immediately after patch rupture in the experiments of Himeno et al. (3) is evidenced by a clearly notable acute depolarization of maximum diastolic potential [shown by arrow in Fig. 5A,a in Himeno et al. (3)]. The depolarization is accompanied by an acute cell contracture (incomplete relaxation), likely resulting from Ca2+ nearly and instantaneously entering the cell from the bath through the patch seal ahead of BAPTA diffusion from the pipette. The artifactual leak currents pose a serious problem during measurements of spontaneous AP firing, because the DD is driven by a net current of a few pico-amperes (2). In other words, small leak currents associated with seal electrical conductance likely shift the current balance of tiny DD currents, artificially increase the DD rate, and offset the true BAPTA effect that would, in the absence of the artifact, suppress the DD and prolong the cycle length.

Result 2

SANC automaticity persists upon acute intracellular BAPTA application in simulations of a numerical M-clock model of SANCs, whereas a recent coupled-clock model [Maltsev-Lakatta (ML) model (6)] predicts pacemaker failure. Since failure was not observed experimentally, the authors concluded that the ML model is inaccurate [Fig. 4 vs. Fig. 5A,a in Himeno et al. (3)].

Our interpretation.

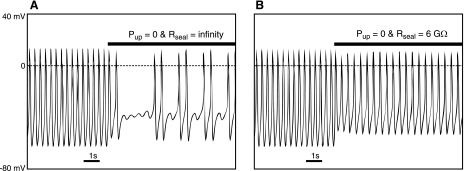

With an introduction of a small leak current (∼8 pA during DD through a 6-GΩ seal resistance) simulating the experimental conditions of Himeno et al. (3), the coupled-clock ML model does not fail but continues to generate spontaneous APs when its Ca2+ clock is acutely disabled (SR Ca2+ pumping rate set to zero; see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Maltsev-Lakatta model (6) simulations of the effect of blocking sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump on pacemaker potentials in the absence and presence of a small artifactual leak conductance upon patch rupture. Normal pacemaking fails when the Ca2+ clock is disabled by setting sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pumping rate to zero (Pup = 0; A) but does not fail when a small leak conductance is introduced into the model simultaneously with the Ca2+ clock disabling (Pup = 0 and Rseal = 6 GΩ; B)

Result 3

While intracellular BAPTA application does not acutely affect SANC automaticity, spontaneous activity is disrupted after several minutes. The authors explain this result based on the long-term effects of Ca2+ on CaMKII and/or the Ca2+-stimulated adenylyl cyclase [See discussion in Himeno et al. (3)].

Our interpretation.

The experimental configuration of Himeno et al. (3) does not permit the study of long-term effects, because upon membrane rupture in transition from perforated patch clamp to whole cell configuration, the perforating agent (amphotericin B) quickly diffuses from patch pipette into cytosol and perforates the whole cell membrane, resulting in large artifactual leak currents and excitability loss.

Result 4

During the first 150 s of cell exposure to a mixture of ryanodine and thapsigargin, the spontaneous AP firing rate is slightly increased but cell contraction is notably decreased [Fig. 7 in Himeno et al. (3)].

Our interpretation.

During such a short time, the drugs' mixture incompletely disables the SR's Ca2+ pumping-release function. Previous studies demonstrated that the effect of thapsigargin to disable SR Ca2+ load requires a longer time, up to 20–30 min (4). Moreover, it is also well known that ryanodine locks Ca2+ release channels [ryanodine receptors (RyRs)] in a subconducting, open state. Therefore, before SR Ca2+ depletion, Ca2+ flux from the SR via RyRs is initially increased by ryanodine, resulting in an acute increase in AP firing rate demonstrated as early as in 1989 (9). This unnatural ryanodine-subconductance open state occurs shortly after ryanodine binding to RyR and can also explain the reduction in contraction amplitude in the experiments of Himeno et al. (3) since it concomitantly impairs the normal process of the excitation-contraction coupling (via Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release, normally effectively triggered by L-type Ca2+ current).

Summary

The issues addressed by Himeno at al. (3) are crucial to test the hypothesis of beat-to-beat regulation of a coupled-clock pacemaker system. In our opinion, however, the methods they have chosen to test these issues have severe shortcomings and therefore preclude rigorous interpretations. Additional experiments employing techniques that do not suffer from such shortcomings are required in this case, for example, simultaneous measurement of intracellular Ca2+ concentration and APs by perforated patch clamp during the entire duration of exposure of SANCs to ryanodine and the photolysis of a caged Ca2+ buffer.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Bogdanov KY, Vinogradova TM, Lakatta EG. Sinoatrial nodal cell ryanodine receptor and Na+-Ca2+ exchanger: molecular partners in pacemaker regulation. Circ Res 88: 1254–1258, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DiFrancesco D. The contribution of the ‘pacemaker’ current (if) to generation of spontaneous activity in rabbit sino-atrial node myocytes. J Physiol 434: 23–40, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Himeno Y, Toyoda F, Satoh H, Amano A, Cha CY, Matsuura H, Noma A. Minor contribution of cytosolic Ca2+ transients to the pacemaker rhythm in guinea pig sinoatrial node cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H251–H261, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Janczewski AM, Lakatta EG. Thapsigargin inhibits Ca2+ uptake, and Ca2+ depletes sarcoplasmic reticulum in intact cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 265: H517–H522, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lakatta EG, Maltsev VA, Vinogradova TM. A coupled SYSTEM of intracellular Ca2+ clocks and surface membrane voltage clocks controls the timekeeping mechanism of the heart's pacemaker. Circ Res 106: 659–673, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maltsev VA, Lakatta EG. Synergism of coupled subsarcolemmal Ca2+ clocks and sarcolemmal voltage clocks confers robust and flexible pacemaker function in a novel pacemaker cell model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H594–H615, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Monfredi OJ, Maltseva LA, Boyett MR, Lakatta EG, Maltsev VA. Stochastic beat-to-beat variation in periodicity of local calcium releases predicts intrinsic cycle length variability in single sinoatrial node cells (Abstract). Biophysical J. 100: 558a, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ponard JG, Kondratyev AA, Kucera JP. Mechanisms of intrinsic beating variability in cardiac cell cultures and model pacemaker networks. Biophys J 92: 3734–3752, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rubenstein DS, Lipsius SL. Mechanisms of automaticity in subsidiary pacemakers from cat right atrium. Circ Res 64: 648–657, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sanders L, Rakovic S, Lowe M, Mattick PA, Terrar DA. Fundamental importance of Na+-Ca2+ exchange for the pacemaking mechanism in guinea-pig sino-atrial node. J Physiol 571: 639–649, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vinogradova TM, Zhou YY, Maltsev V, Lyashkov A, Stern M, Lakatta EG. Rhythmic ryanodine receptor Ca2+ releases during diastolic depolarization of sinoatrial pacemaker cells do not require membrane depolarization. Circ Res 94: 802–809, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]