Abstract

Wound healing of the gastrointestinal mucosa is essential for the maintenance of gut homeostasis and integrity. Enteric glial cells play a major role in regulating intestinal barrier function, but their role in mucosal barrier repair remains unknown. The impact of conditional ablation of enteric glia on dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced mucosal damage and on healing of diclofenac-induced mucosal ulcerations was evaluated in vivo in GFAP-HSVtk transgenic mice. A mechanically induced model of intestinal wound healing was developed to study glial-induced epithelial restitution. Glial-epithelial signaling mechanisms were analyzed by using pharmacological inhibitors, neutralizing antibodies, and genetically engineered intestinal epithelial cells. Enteric glial cells were shown to be abundant in the gut mucosa, where they associate closely with intestinal epithelial cells as a distinct cell population from myofibroblasts. Conditional ablation of enteric glia worsened mucosal damage after DSS treatment and significantly delayed mucosal wound healing following diclofenac-induced small intestinal enteropathy in transgenic mice. Enteric glial cells enhanced epithelial restitution and cell spreading in vitro. These enhanced repair processes were reproduced by use of glial-conditioned media, and soluble proEGF was identified as a secreted glial mediator leading to consecutive activation of epidermal growth factor receptor and focal adhesion kinase signaling pathways in intestinal epithelial cells. Our study shows that enteric glia represent a functionally important cellular component of the intestinal epithelial barrier microenvironment and that the disruption of this cellular network attenuates the mucosal healing process.

Keywords: enteric glial cells, FAK, enteric nervous system, epithelial restitution, intestinal epithelial barrier

chronic or acute intestinal inflammatory processes often lead to the destruction of the intestinal epithelial barrier (IEB) (38). Resolution of intestinal inflammation is dependent on repair processes that restore normal intestinal architecture. Chronic inflammatory diseases present failure in mucosal repair processes, leading, for instance, to chronic ulceration and to increased risk of associated colonic dysplasia. Furthermore, mucosal healing has been proposed recently as a treatment goal in inflammatory bowel diseases (12).

Wound healing or mucosal healing is a cellular mechanism that preserves the structural and functional integrity of the IEB. Wound repair of the intestinal mucosa involves three processes including epithelial restitution, cell proliferation, and differentiation (30). Although these processes overlap in vivo (30), the most rapid cellular event following tissue injury is epithelial restitution, which restores mucosal continuity via cell migration and spreading on the underlying matrix (22).

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is a nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinase that regulates several different pathways controlling cell motility, proliferation, and survival. One mode of FAK regulation is its autophosphorylation on tyrosine 397 following integrin clustering. FAK phosphorylation on tyrosine 397 promotes Src binding, resulting in conformational activation of the FAK-Src signaling complex. The FAK-Src signaling complex then recruits or phosphorylates several regulatory proteins involved in cell adhesion, motility, growth, and survival (19).

The cellular microenvironment of the intestinal mucosa can influence epithelial restitution of the IEB. For instance, neutrophils or intestinal subepithelial myofibroblasts can promote wound repair (4, 24). Another major cellular component of the IEB microenvironment is the enteric nervous system (ENS). The ENS is composed of enteric neurons and glial cells (EGC) organized into an integrative neuronal network localized along the entire gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Although its role in the control of GI motility is well known, emerging data suggest that the ENS can also be a major regulator of IEB functions. In particular, enteric neurons can directly inhibit intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) proliferation via the release of vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) (33). Moreover, VIPergic neuronal pathways have been shown to reduce IEB paracellular permeability (21) and to protect the IEB from Citrobacter rodentium infection (9).

Besides neurons, special consideration has been recently given to EGC in the control of IEB functions. EGC, which outnumber enteric neurons by a factor of 4 to 10, share common markers and properties with astrocytes of the central nervous system (CNS) (26, 29), which are known to promote blood-brain barrier functions (1). In vivo ablation of EGC in transgenic (Tg) mice leads to dramatic IEB alterations (7, 10) associated with increased IEB permeability that precedes intestinal inflammation (3, 28). Furthermore, EGC inhibit IEC proliferation via the release of TGF-β1 (20) and decrease IEB permeability and mucosal inflammation via the secretion of S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) (28). Nevertheless, whether EGC also control epithelial restitution remains unknown.

In this study, we demonstrate that conditional ablation of EGC worsens mucosal damage after dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) treatment and delays mucosal healing following diclofenac-induced small intestinal enteropathy in GFAP-HSVtk mice. In vitro, we show using a noncontact coculture model system that EGC promote wound healing by increasing epithelial restitution and cell spreading following mechanical injury to IEC monolayers. This response is mediated, in part, by glial-secreted proEGF and activation of FAK-dependent pathways in IEC.

METHODS

Immunohistochemistry, Immunofluorescence, and Electron Microscopy in Human Mucosa

Fragments of human healthy tissue were taken at 10 cm from the tumor from patients undergoing surgery for colon carcinoma. According to the guidelines of the French Ethics Committee for Research on Human Tissues, these were considered as “residual tissues” and were not relevant to pathological diagnosis.

For whole mount immunohistochemistry, specimens were pinned flat on wax-based Petri dishes before fixation with PBS-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) at 4°C overnight. After treatment with PBS-0.05% thimerosal overnight and 0.1% NaCNBH3 for 30 min, mucosal whole mounts were dissected under stereomicroscopic control. The tissue was preincubated with 10% normal goat serum diluted in PBS-0.5% Triton X-100 for 1 h followed by incubation for 48 h with polyclonal rabbit anti-S-100β (1:400, Dako). After extensive rinsings in PBS, whole mounts were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 2 h, rinsed in PBS, and incubated with the avidin-biotin complex (Vectastain ABC Elite kit, Vector) conjugated with horseradish peroxidase according to the instructions of the supplier. Peroxidase activity was detected with the chromogen 4-chloro-1-naphthol. Whole mounts were rinsed in PBS, placed on slides, covered with Aquatex (Merck), and examined with an Axiophot microscope.

For immunofluorescence studies, after fixation with PBS-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) at 4°C overnight, paraffin-embedded sections or dissected mucosal whole mounts were preincubated with 10% normal goat serum diluted in PBS-0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min followed by incubation for 24 h with the following primary antibodies: polyclonal rabbit anti-S-100β (1:400, Dako), monoclonal mouse anti-smooth muscle-α actin (1:500, Dako). Alexa Fluor 488 (goat anti-rabbit, 1:250, Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 546 (goat anti-mouse, 1:250, Invitrogen) were used as secondary antibodies. 4,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Roche) was used as nuclear counterstaining agent. Sections and slide-mounted whole mounts were analyzed by a fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 200M, Zeiss) equipped with an adequate filter system.

For transmission electron microscopy, small mucosal samples (∼5 mm border length) were fixed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde at pH 7.4 for 24 h. The specimens were postfixed in 1% OsO4 and stained en bloc with 2% uranylacetate. After dehydration in graded alcohols, the specimens were embedded in Araldite. Semithin sections were stained with methylene blue and azure II to visualize the regions of interest. Ultrathin sections were cut and stained with lead citrate and examined with a transmission electron microscope (Phillips, EM 109) linked to a digital camera and imaging system (analySIS, Soft Imaging System, Munster, Germany).

Conditional Ablation of EGC in Tg Mice

Twelve-week-old GFAP-HSVtk Tg mice were used to conditionally ablate EGC as described previously (28). All procedures were performed with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval and in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for use of live animals.

DSS Studies

GFAP-HSVtk Tg and nontransgenic (NTg) littermates received 5% DSS in the drinking water ad libitum for 7 days and tissues were collected on day 8. All animals received subcutaneously ganciclovir (GCV) (Hoffman-LaRoche, Nutley, NJ) at a rate of 100 mg·kg−1·day−1 via miniosmotic pumps (Alzet, Durect, Cupertino, CA) during the 7 days of DSS treatment. The method used for mucosal damage quantification was as previously described (32), and the scoring was done blindly by two observers.

DCF-Induced Small Intestinal Enteropathy Studies

All animals received subcutaneously GCV at a rate of 100 mg·kg−1·day−1 using miniosmotic pumps. On day 6 of GCV treatment, GFAP-HSVtk and NTg littermates received an intraperitoneal injection of 60 mg/kg diclofenac sodium salt DCF (Sigma-Aldrich) as previously described (25), and small intestinal tissues were collected after 18 and 48 h. The method used for mucosal damage quantification was as previously described (25), and the scoring was done blindly by two observers.

Cell Cultures and Reagents

JUG2 cell line was obtained from ENS primary culture derived from rat embryonic intestine (8). After 13 days of culture, primary cultures were trypsinized and seeded in serum-containing media after differential centrifugation. Following 7 days of culture, isolated areas of morphological glial cells-like were trypsinized using cloning cylinder and seeded in culture flask in serum-containing media. After 1 mo, the cells were assessed for glial, neuronal, and myofibroblast markers by immunohistochemistry. They were immunoreactive for GFAP, Sox10, and S-100β, all glial markers, but not for Tuj-III, PGP9.5, neuronal markers, and α-smooth muscle actin, a myofibroblast marker. Purity of the JUG2 cell line was estimated of 96 ± 3% (n = 3) according to the ratio of number of Sox10-positive cells per number of DAPI-positive cells.

EGC lines and Caco-2 cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM (4.5 g/l glucose; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FBS (Abcys), 2 mM glutamine (Invitrogen), 50 IU/ml penicillin (Invitrogen), and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). CCD18Co cells (normal human colon fibroblasts; ATCC) were cultured in MEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acid (Invitrogen), 50 IU/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin.

EGC lines CRL2690 (ATCC) and JUG2 were seeded at 50,000 cells/ml and maintained in culture for 4 days at which time EGC-conditioned medium (CM) was prepared from EGC supernatants. For wound healing experiments, Caco-2 cells were seeded onto six-well Transwell filters (0.40 μm porosity, Corning) at 286,000 cells/ml and cultured for 15 days after reaching confluence. For cell spreading, Caco-2 cells were seeded onto 12-well filters at 140,000 cells/ml and processed for experiments 1 day after their seeding. Caco-2 cells were cocultured in the presence of EGC or CCD18Co myofibroblasts seeded on the bottom of 6- or 12-well plates or in the presence of either EGC-CM, PP2 (Calbiochem), GM6001 (Millipore), PD153035 (Calbiochem), EGFR blocking antibody (Calbiochem), EGF blocking antibody (R&D Systems), hEGF (Sigma), rEGF (R&D Systems), or hproEGF (R&D Systems).

Wound Healing Experiments

Caco-2 monolayers were wounded by using a tip attached to a 0.5- to 10-μl pipette. Each wound was photographed at 0 and 24 h by using a microscope (Axiovert 200M; Zeiss; objective lens: A-plan ×5/0.12) and the damaged surface area was quantified with DP-Soft software (Olympus). Epithelial restitution was calculated as the percentage of remaining wounded zone area as follows: 100 − [100 × (initial wounded zone surface − final wounded zone surface)/initial wounded zone surface]. The monolayers were cultured with or without EGC, EGC-CM (in presence or absence of pharmacological agents), and CCD18Co 24 h prior to wounding and maintained an additional 24 h in culture. Transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) of monolayers was measured with an EVOM resistance meter (World Precision Instruments). Filter-grown cells were fixed and processed for immunocytochemistry to detect zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), used here to determine the surface area of IEC located on the first five consecutive circumferential cell layers encompassing the wound. All measurements were performed in a blinded fashion.

Cell Spreading Experiments

After 24 h of coculture, IEC were fixed and processed for immunocytochemistry to detect ZO-1 as previously described (20). Monolayers were viewed with a fluorescence microscope (BX 51; Olympus) connected to a video camera (DP50, Olympus). Cell surface area was measured with DP-Soft software (Olympus). An average of 321 ± 13 IEC surface areas were analyzed for each experimental condition.

Plasmid Transfection

Caco-2 cells were transfected with FRNK (FAK-related nonkinase) plasmid construct fused with GFP (FRNK/GFP; kindly provided by Dr. Hervé Enslen), or with the empty vector as a control (mock/GFP). IEC were transfected on six-well filters once reaching 30–40% confluence by using Lipofectamine LTX and Reagent Plus system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol using 3 μg/well of DNA equally distributed between the apical and basolateral compartments for 6 h. Cell spreading experiments were carried out 24 h later. For cell spreading analysis, GFP-positive cells transfected with FRNK/GFP were assumed to express FRNK and results were compared with those obtained with mock/GFP-transfected cells.

Lentiviral shRNA PTK2 Infection of Caco-2 Cells

To silence the expression of FAK gene, also called PTK2, 2.5 × 104 Caco-2 cells were plated onto six-well plates and grown for 24 h with complete culture medium. Cells were washed twice with PBS 30 min prior the infection. 2.5 × 104 PTK2 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) lentiviral particles (SHVRS, NM_005607, Sigma) were added in each well and cells were then incubated for 24 h. Five different clones of PTK2 shRNA and a nonspecific target shRNA control were tested. Solution containing viral particles was removed and replaced by fresh complete medium. Caco-2 cells were trypsinized 5 days postinfection and plated in culture flasks. Cells were next selected by adding 50 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma) to the culture medium. PTK2 expression levels in the different clones were measured by Western blot. Only the results obtained with cells derived from the clone presenting 50% of PTK2 expression silencing are reported in the present study.

Human Colonic Biopsy Specimens

Histologically normal mucosal biopsies were taken during colonoscopy for cancer screening from 16 healthy patients (aged 34–85 yr). Patients gave their informed consent to participate in the study, and all procedures were performed with institutional approval.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR Studies

Extraction of total RNA was performed with RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and 1 μg of purified total RNA was processed for reverse transcription using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. FAK mRNA expression study in Caco-2 cells after 24 h of culture in presence of EGC or EGC-CM was carried out on a Rotor-Gene thermocycler (Ozyme). PCR amplifications were performed by use of Platinum Taq polymerase kit (Invitrogen) combined with the use of SYBR green (Sigma). FAK mRNA expression study in ileojejunal fragments of Tg mice was achieved by using a MyiQ thermocycler (Bio-Rad). PCR amplifications were performed by use of the ABsolute Blue SYBR green fluorescein kit (ABgene).

Western Blot Studies

Caco-2 cells, cultured for 24 h with or without EGC, or EGC were lysed either with RIPA (Millipore) completed with proteases inhibitor tablets (Complete, Roche) or processed for Triton X fractionation. For Triton X fractionation, cells were lysed with Triton lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.3 M sucrose, 25 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgCl2) containing proteases inhibitor (Complete, Roche), serine/threonine phosphatases inhibitors (Sigma) and 2 mM NaVO4. After agitation, insoluble material was removed by centrifugation and supernatant was defined as the Triton X-soluble fraction. The pellet was extracted with a SDS lysis buffer (20 mM Tris·HCl, 2.5 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 0.5 μg/ml DNase I) completed with protease/phosphatase inhibitors and NaVO4. Triton X-insoluble fraction was obtained after agitation and removal of insoluble material by centrifugation. Samples were processed for electrophoresis using NuPAGE MES SDS buffer kit (Invitrogen) and separated on 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (NuPAGE, Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking, blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in TBS with 5% nonfat dry milk for FAK (clone 4.47, 1:1,000, Upstate), FAKc20 (1:200, Santa Cruz), cyclophilin-A (1:5,000, Abcys), RPS6 (1:1,000; Bethyl), and rEGF (16 μg/ml, R&D Systems) or in TBS with 4% BSA and 0.1% Tween20 for FAK phosphospecific antibody (phosphorylated Y397-FAK) (1:1,000; Biosource). Immunoblots were probed with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) and visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL Plus, Amersham). Quantitative analysis was performed by measuring band densities with ImageJ.

Time-Lapse Videos

Time-lapse videos were taken by using a microscope (Leica DMI6000; Leica Microsystems) at 37°C with 5% CO2 in the culture medium described above. Images were taken with a camera (Coolsnap HQ2; Photometrics) and Metamorph software (Molecular Devices). The images stacks were compiled by use of Metamorph.

Statistics

Data were expressed as means ± SE. Paired or unpaired t-test, Mann-Whitney test, or two-way ANOVA was performed to compare different groups. Pearson's correlation coefficient was measured to test for interdependence between variables. Differences were considered as significant for a P value of less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Enteric Glial Cells Are a Major Cellular Constituent of the Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Microenvironment

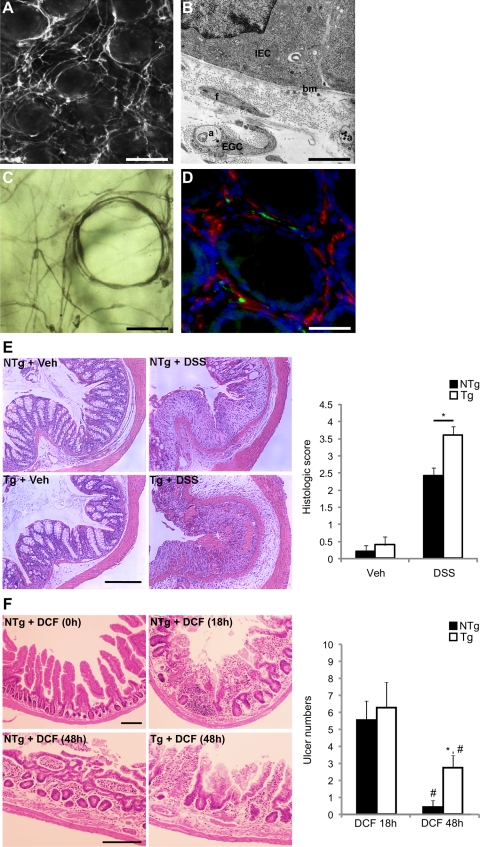

Immunohistochemical staining for glial S-100β-immunoreactivity in healthy human colonic mucosa revealed a dense network of EGC in close proximity to epithelial cells of the colonic crypts (Fig. 1, A and C) and extended all the way up to the surface mucosa. This observation was consistent with the presence of GFAP-positive EGC and their processes throughout the lamina propria, tightly surrounding intestinal crypts previously described in Ref. 7. The positioning of these EGC was reminiscent of pericryptal myofibroblasts. However, S-100β-immunoreactive EGC did not coexpress α-smooth muscle actin, which labeled pericryptal myofibroblasts (Fig. 1D). Ultrastructural analysis confirmed the presence of EGC processes within close proximity of the intestinal epithelial basement membrane (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Enteric glial cells (EGC) are a major cellular component of the intestinal epithelial barrier (IEB) microenvironment. A: S-100β-immunoreactive EGC form a dense cellular network surrounding the intestinal crypts (human colonic mucosa; ×100; scale bar 100 μm). B: electron microscopy highlights the close proximity (≅ 1 μm) between EGC ensheathing axons (a) and intestinal epithelial cells (IEC), the basal membrane (bm), as well as myofibroblasts (f) (human colonic mucosa; ×20,000; scale bar 1 μm). C: S-100β-immunoreactive EGC are also present in the periglandular region of the human colonic crypts (×200; scale bar 50 μm). D: immunofluorescence labeling of human colonic mucosa using antibodies directed against S-100β (green) and α-smooth muscle actin (red) shows an absence of colocalization of these two markers. Nuclei were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue) (×200; scale bar 50 μm). E, left: colonic mucosal damage induced by 7 days of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) treatment was increased in transgenic (Tg) mice compared with their nontransgenic (NTg) littermates (hematoxylin and eosin-stained colonic specimens; scale bar 200 μm; Veh, vehicle). Right: histological scoring confirms the increase in the severity of the DSS-induced colitis in Tg mice (open bars) compared with NTg mice (solid bars) (n = 5; P = 0.032; Mann-Whitney rank sum test). F, left: histopathological characterization of the effects of EGC ablation on diclofenac sodium salt (DCF)-induced ulceration. Mucosal damage in the 3rd quartile of the small intestine in Tg was similar compared with their NTg littermates 18 h after DCF treatment. In contrast, 48 h after DCF treatment, mucosal damage was significantly lower in NTg mice compared with their Tg littermates (scale bars: 200 μm). Right: whole-mount scoring of ulcer numbers in the 3rd quartile was significantly lower in NTg (solid bars) compared with Tg (open bars) 48 h after DCF treatment (n = 4–8; 2-way ANOVA; *P < 0.05 compared with Tg 48 h; #P < 0.05 compared with their respective control at 18 h).

Conditional Ablation of Enteric Glia Worsens Mucosal Damage and Impairs Healing in Two In Vivo Models of Mucosal Injury

To characterize in vivo the role of EGC in intestinal mucosal healing, we used two distinct models of mucosal injury, i.e., DSS-induced mucosal damage and DCF-induced enteropathy.

EGC deletion increases the severity of DSS-induced mucosal lesions.

DSS was administered orally to GFAP-HSVtk Tg mice, which were simultaneously treated with GCV as previously described in Refs. 7 and 28. GCV treatment led to the ablation of GFAP-positive EGC, in particular, those tightly surrounding intestinal crypts as shown in (7). Seven days of GCV treatment in Tg mice receiving vehicle control was not associated with any mucosal or inflammatory lesions of the colon (Fig. 1E). However, coadministration of DSS to Tg animals resulted in significantly larger areas of mucosal damage and inflammatory infiltrates compared with NTg mice receiving DSS and GCV (Fig. 1E). Mucosal damage was characterized by areas of epithelial ulceration and crypt damage with infiltrating polymorphonucleocytes and the highest histological damage score was recorded following EGC ablation (3.6 ± 0.25 vs. 2.4 ± 0.25, for Tg and NTg mice receiving DSS and GCV, respectively; n = 5; P = 0.032) (Fig. 1E).

Loss of EGC delays the healing of DCF-induced mucosal lesions.

DCF was administered to induce NSAID enteropathy in NTg mice and in GFAP-HSVtk Tg littermates in which EGC were simultaneously ablated by GCV (7, 28). Control NTg mice also received subcutaneous GCV. As has been previously described (25), severe DCF-induced small intestinal enteropathy was evident in the small intestine of mice after 18 h of drug administration (Fig. 1F). No significant differences were evident in the total number or in the distribution of small intestinal lesions detected in Tg vs. NTg mice receiving DCF at 18 h. Moreover, pathology was most prominent in the jejunum-ileum (3rd quartile), which is also the region where EGC are most significantly ablated by GCV (7). No pathology was evident in NTg or Tg mice receiving GCV only. In DCF-treated NTg mice, the enteropathy had largely resolved within 48 h (Fig. 1F), as previously described (25). In contrast, in Tg animals, a significant enteropathy was still apparent after this time, indicating that mucosal healing in response to DCF was compromised following EGC ablation (Fig. 1F).

Enteric Glia Promote Epithelial Restitution by Increasing Intestinal Epithelial Cell Spreading

To study the direct effects of EGC on intestinal epithelial wound healing, we next used a coculture model of EGC and IEC.

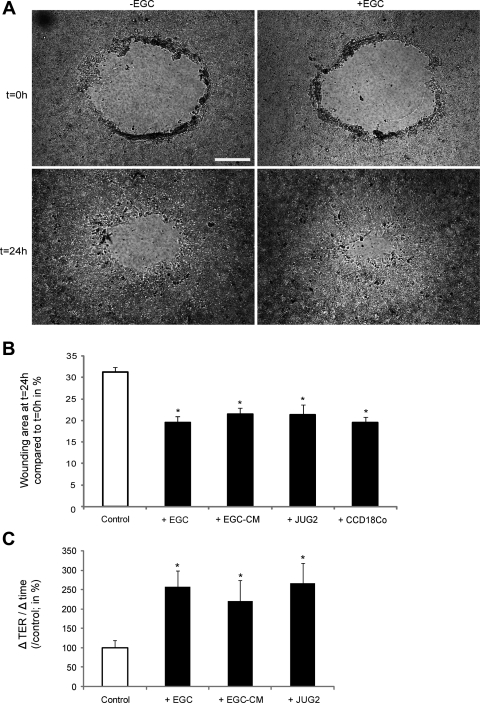

EGC increase intestinal epithelial wound healing in vitro.

At 24 h following mechanically induced injury, wounded areas were significantly reduced when the IEC monolayers were cultured with EGC compared with controls (IEC monolayers cultured alone) (19.2 ± 1.1 vs. 31.7 ± 1.8%, respectively; n = 7; P = 0.003) (Fig. 2, A and B and Supplemental Video S1; the online version of this article contains supplemental data). In addition, the increase in TER was significantly greater when IEC were cultured with EGC compared with controls (257.6 ± 41.3 vs. 100.0 ± 20.3%, respectively; n = 7; P = 0.007) (Fig. 2C). Similar results were obtained with another nontransformed EGC line (JUG2) (Fig. 2, B and C) and with another IEC line (T84) (unpublished data). Moreover, the EGC-induced increase in epithelial restitution and resistance recovery were reproduced by EGC-CM (Fig. 2, B and C). These results indicate that EGC enhance epithelial wound repair via the secretion of one or more soluble factors. To validate our experimental restitution model, we also demonstrated a similar increase in epithelial restitution in IEC monolayers cocultured with the human colonic fibroblast cell line, CCD18Co (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

EGC promote intestinal epithelial wound healing. A: wound surface areas of IEC monolayers were significantly reduced after coculture with EGC compared with controls (scale bar 200 μm). B: EGC or EGC-conditioned medium (EGC-CM) significantly reduced wounded surface areas compared with controls (n = 10; P < 0.001; t-test and n = 11; P = 0.002; paired t-test, respectively). A nontransformed EGC line (JUG2) also increased epithelial restitution (n = 3; P < 0.05; t-test) as well as the human colonic fibroblast cell line CCD18Co (n = 6; P < 0.001; t-test). C: EGC and EGC-CM as well as JUG2 induced a significant increase in transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) recovery. Data are presented as a percentage after normalization to controls (n = 7; P = 0.003; t-test, n = 6; P = 0.014; paired t-test and n = 3; P < 0.05; t-test, respectively). *Significantly different.

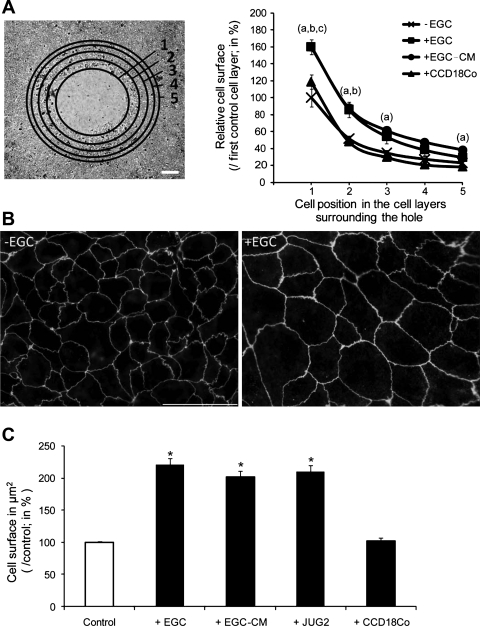

EGC promote epithelial restitution by increasing IEC spreading.

We next sought to determine whether EGC effects on epithelial restitution were associated with an increase in IEC spreading. Under control conditions, a significant increase in IEC spreading was recorded in the first three circumferential cell layers surrounding the wounded zone compared with the fifth cell layer (Fig. 3A). EGC significantly increased IEC surface areas of the first three circumferential cell layers compared with controls (Fig. 3A). Similarly, EGC-CM induced a significant increase in IEC surface areas of the first two circumferential cell layers compared with controls (Fig. 3A). By contrast, CCD18Co induced a significant increase in IEC surface areas of the first circumferential cell layer only (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

EGC increase IEC spreading. A, left: the cell surface areas of the first 5 circumferential cell layers surrounding the wounded areas were evaluated following staining for zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) (scale bar 200 μm). Right: EGC and EGC-CM induced a significant increase in IEC spreading in the first 3 and 2 cell layers respectively compared with controls (a and b, respectively; n = 6; P < 0.05; t-test). By contrast, CCD18Co induced a significant increase in IEC spreading only in the first cell layer compared with controls (c; n = 3; P < 0.05; t-test). B: photomicrograph of Caco-2 cells stained with ZO-1 antibody revealed a significant increase in cell surface area induced by EGC (+EGC) compared with controls (−EGC) (scale bar 50 μm). C: quantitative analysis of IEC surface areas showed a significant increase in cell surface area induced by EGC and EGC-CM compared with controls (n = 4; P < 0.001; t-test and n = 3; P = 0.009; paired t-test, respectively). The nontransformed EGC line JUG2 induced a significant increase in IEC cell surface area (n = 4; P < 0.05; t-test). The human colonic fibroblast cell line CCD18Co had no effect on IEC spreading. *Significantly different.

To confirm that EGC promoted IEC spreading, EGC effects on IEC spreading were studied by using Caco-2 cells seeded at low density. After 24 h of incubation, EGC significantly increased Caco-2 cell spreading compared with controls (220.9 ± 9.2 vs. 100.0 ± 2.2%, respectively; n = 4; P ≤ 0.001) (Fig. 3, B and C and Supplemental Video S2). This result was also reproduced by primary JUG2 EGC and by EGC-CM (Fig. 3C). By contrast, when IEC were cocultured with CCD18Co, no increase in cell spreading was observed (Fig. 3C).

Enteric Glia Promote Epithelial Wound Healing Via Activation of FAK-Dependent Signaling Pathways

FAK is a major regulator of epithelial wound healing. We therefore studied whether EGC promote IEB wound repair via activation of FAK-dependent pathways.

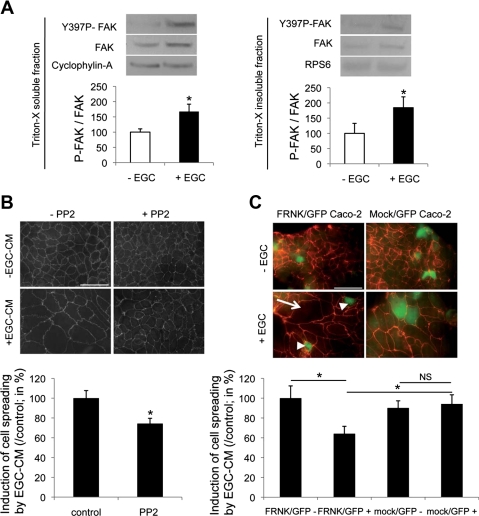

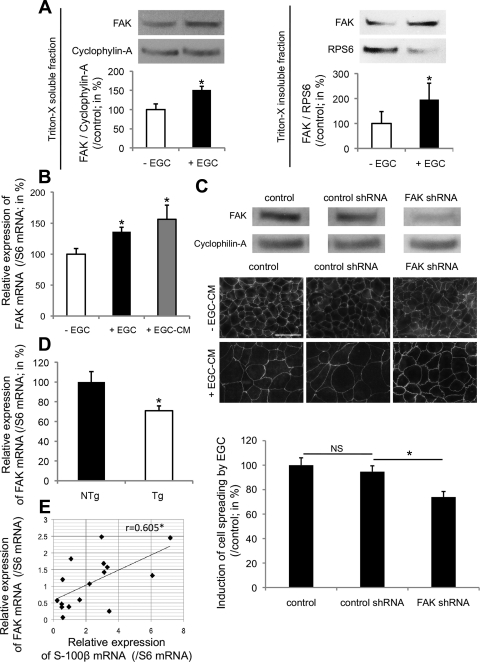

EGC promote epithelial wound repair by increasing FAK activity in IEC.

Firstly, we demonstrated that EGC induced a significant increase in Y397-FAK phosphorylation in Triton X-soluble and -insoluble IEC lysate fractions (Fig. 4A). We then tested the effects of FAK inhibition on both EGC-induced epithelial restitution and IEC spreading using PP2, a pharmacological inhibitor of Src-mediated activation of FAK. When combined with EGC-CM, PP2 inhibited EGC-CM effects on epithelial restitution compared with controls (31.6 ± 16.1 vs. 100.0 ± 11.4%, respectively; n = 6; P = 0.006). The effects of EGC-CM on IEC spreading were also significantly inhibited by PP2 (Fig. 4B). To confirm these findings, we transfected Caco-2 cells with a dominant-negative construct of FAK, FRNK, fused to GFP. Compared with mock-transfected controls, EGC-induced cell spreading was significantly reduced in FRNK/GFP-positive cells (64.1 ± 7.5 vs. 94.2 ± 9.2%, respectively; n = 5; P = 0.035) (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

EGC increase epithelial restitution via induction of FAK-dependent pathways. A: EGC induced a significant increase in FAK autophosphorylation (Y397P-FAK) in Triton X-soluble (left) and Triton X-insoluble (right) fractions of IEC compared with IEC cultured alone (n = 4; P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). B: in the presence of PP2, the effects of EGC-CM on cell spreading were significantly reduced (n = 4; P = 0.008; paired t-test). C: transfection of IEC with FRNK-GFP (FRNK/GFP Caco-2) inhibited EGC effects on IEC spreading, whereas IEC transfection with mock-GFP plasmid (mock/GFP Caco-2) had no effect. Induction of IEC spreading by EGC (arrow) was significantly reduced in FRNK-GFP-transfected cells (arrowheads) compared with mock-GFP-positive cells (n = 5; P = 0.007; t-test; scale bar 50 μm). *Significantly different; NS, not significant.

EGC Control Epithelial Restitution via the Regulation of FAK Expression

EGC increase IEC spreading by increasing FAK expression in vitro.

We next aimed at determining whether EGC-mediated wound healing was associated with regulated FAK expression. Firstly, EGC significantly increased FAK protein levels in Triton X-soluble and -insoluble IEC lysate fractions compared with controls (Fig. 5A). This increase in FAK protein levels was most likely due to elevated FAK mRNA expression as a result of EGC coculture or EGC-CM (Fig. 5B). Next, the involvement of FAK in the EGC effects on IEC spreading was evaluated in Caco-2 cells transfected with FAK shRNA lentiviral constructs. Silencing of FAK expression markedly reduced EGC-CM-mediated induction of IEC spreading compared with nonspecific target shRNA transfected controls (74.0 ± 4.5 vs. 94.7 ± 4.8%, respectively; n = 4; P = 0.013) (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

EGC promote epithelial restitution via the regulation of FAK expression. A: EGC induced a significant increase in FAK expression in Triton X-soluble (left) and Triton X-insoluble (right) fractions of IEC compared with controls (n = 4; P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). B: real-time quantitative PCR analysis reported a significant increase in FAK mRNA expression in IEC cultured with EGC or EGC-CM (n = 5; P = 0.006, t-test and n = 5; P = 0.008, paired t-test, respectively). C, top: transfection of IEC with FAK short hairpin RNA (shRNA) significantly decreased FAK protein expression compared with IEC transfected with nonspecific target control shRNA or noninfected IEC (control). Middle and bottom: transfection of IEC with FAK shRNA significantly inhibited EGC-CM effects on IEC spreading compared with control shRNA (n = 4; P = 0.013; paired t-test; scale bar 50 μm). D: real-time quantitative PCR analysis showed that in vivo ablation of EGC reduced the expression of FAK mRNA expression in intestinal fragments from Tg mice (Tg) compared with controls (NTg) (n = 7; P = 0.021; t-test). E: real-time quantitative PCR analysis of human colonic mucosal biopsies revealed a significant positive correlation between FAK and S-100β mRNA expression (n = 16; Pearson's correlation coefficient: 0.605; P = 0.013). *Significantly different.

EGC control FAK expression in vivo.

To further validate the EGC-mediated control of FAK expression, we studied FAK mRNA expression in intestinal segments following EGC-ablation in GFAP-HSVtk Tg mice. A significant decrease in FAK mRNA abundance was evident in Tg mice receiving GCV compared with their NTg littermates [70.9 ± 5.0 (n = 7) vs. 100.0 ± 10.6% (n = 5), respectively; P = 0.021] (Fig. 5D). Moreover, a significant positive correlation between S-100β and FAK mRNA abundance was evident in human colonic biopsies (Fig. 5E).

Enteric Glia Promote Wound Healing via Secretion of proEGF and Activation of EGFR-Dependent Pathways in IEC

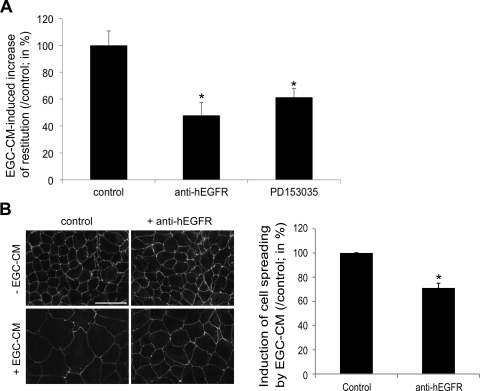

Blocking of EGFR activation inhibits EGC-CM effects on epithelial restitution.

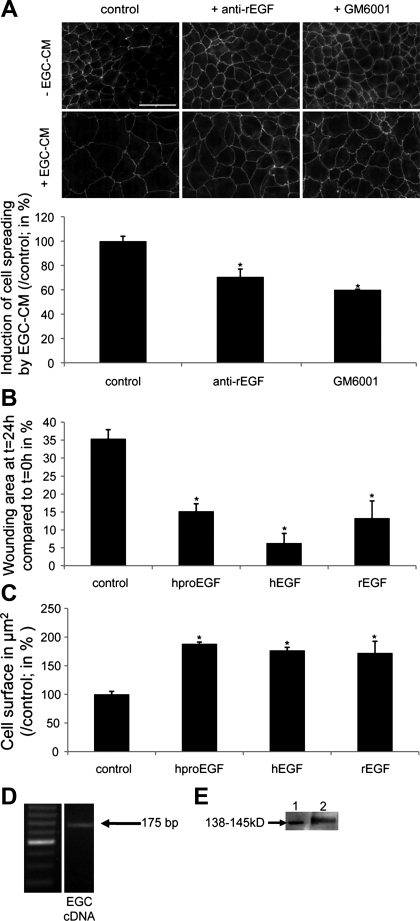

To examine whether EGFR activation is involved in IEC response to EGC, we added an EGFR blocking antibody to EGC-CM. Neutralizing EGFR antibody significantly inhibited the EGC-CM-mediated effects on epithelial restitution (Fig. 6A). Similar results were obtained when adding an inhibitor of the EGFR tyrosine kinase activity (PD153035) to EGC-CM (Fig. 6A). Addition of the EGFR blocking antibody to EGC-CM also led to an inhibition of the EGC-CM-induced increase of IEC spreading (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, the addition of an EGF blocking antibody to EGC-CM led to inhibition of EGC-CM effects on IEC spreading (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, the addition of an inhibitor of metallo-matrix proteinases (MMPs) (GM6001) to EGC-CM significantly inhibited EGC-CM-induced cell spreading (Fig. 7A), suggesting the presence of EGF precursor forms in EGC-CM. Consistent with this observation, treatment of IEC with proEGF led to a significant increase in epithelial restitution and IEC spreading (Fig. 7, B and C). This proEGF-mediated induction of IEC spreading was significantly reduced by GM6001 (33.1 ± 1.8%; n = 4; P < 0.001). Human and rat EGF also induced a significant increase in epithelial restitution (Fig. 7B), as well as a significant increase in IEC spreading (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 6.

EGC promote intestinal epithelial wound healing via EGFR-dependent pathways. A: addition of an EGFR neutralizing antibody (anti-hEGFR, 2 μg/ml) significantly blocked the increase in epithelial restitution induced by EGC-CM (n = 3; P = 0.007; paired t-test). Similarly, PD153035 (1 μM), a specific inhibitor of EGFR kinase, significantly reduced the EGC-CM-induced epithelial restitution (n = 6; P = 0.035; paired t-test). B: EGC-mediated increase in IEC spreading was significantly decreased by the addition of anti-hEGFR (2 μg/ml) (n = 4; P = 0.009; paired t-test; scale bar 50 μm). *Significantly different.

Fig. 7.

EGC secrete proEGF, and EGF neutralizing antibody and metallo-matrix proteinase (MMP) inhibitor decrease the EGC-CM-induced IEC spreading. A: EGF neutralizing antibody (16 μg/ml) and the MMP inhibitor GM6001 (10 μM) reduced the EGC-CM-induced IEC spreading (n = 3; P = 0.011; paired t-test and n = 3; P = 0.038; paired t-test, respectively; scale bar 50 μm). B: human proEGF (100 ng/ml), human EGF (1 ng/ml), and rat EGF (20 ng/ml) increased epithelial restitution (n = 3; P = 0.001, P = 0.01 and P = 0.008; t-test; respectively). C: human proEGF (100 ng/ml), human EGF (1 ng/ml), and rat EGF (20 ng/ml) significantly increased IEC spreading (n = 4; P < 0.001, P = 0.029 and P < 0.001; t-test, respectively). D: PCR studies demonstrating EGF mRNA accumulation in EGC. E: Western blot experiments showing immunoreactive proEGF in EGC-CM (lane 1: recombinant human proEGF: 138–145 kDa; lane 2: EGC-CM). *Significantly different.

Enteric glial cells secrete proEGF.

Finally, we investigated the source of EGFR activation in EGC-CM by testing whether proEGF was synthesized and secreted by EGC. EGF mRNA was expressed in EGC (Fig. 7D), and proEGF, but not the 6-kDa form of EGF, was detected in EGC-CM by immunoblotting (Fig. 7E).

DISCUSSION

The present study reports major findings concerning the role of EGC in the control of IEB functions. In vivo, conditional ablation of the EGC population in adult Tg mice led to increased mucosal damage after DSS treatment and impaired mucosal healing following DCF-induced small intestinal enteropathy, indicating that EGC play an active protective role toward IEB under pathological conditions. This barrier protecting role was also demonstrated in vitro where EGC promoted epithelial repair in response to injury by increasing IEC spreading. EGC-induced epithelial wound healing involved the regulation of FAK expression and activity in IEC. Furthermore, proEGF was identified as a major soluble glial mediator responsible for the EGC-induced increase of epithelial wound repair.

This study further strengthens the concept that the IEB is regulated by its immediate cellular neighbors, which include myofibroblasts, immune and neuroglial cells, and the microbiota. Here we demonstrate that EGC is a novel and pivotal cellular regulator of the IEB in response to mucosal injury. The DSS-injury studies show that specific EGC dysfunction exacerbates colitis-induced mucosal damage, highlighting two putative roles for EGC in the maintenance of the IEB homeostasis: a protective (anti-inflammatory) role and a repair process-inducing role. The inflammatory response that is evident in this model is clearly associated with the enhanced DSS-induced injury as no inflammation is manifest in Tg animals receiving vehicle control alone for a similar duration. This is in agreement with an earlier study where conditional ablation of EGC preceded inflammation that was only evident after 9 days of GCV treatment (28). Recent findings demonstrate that EGC can exert protective effects on IEB functions in inflammatory conditions via the release of mediators such as GSNO (28, 35). To further validate our hypothesis that EGC also favor IEB functions by promoting mucosal healing, we used a short-term mucosal injury model using DCF to induce focal injuries in the small intestinal mucosa followed by rapid healing, involving cell restitution. The DCF-enteropathy studies demonstrated that EGC dysfunction significantly delayed mucosal healing, further strengthening the repair-promoting role of EGC in the maintenance of IEB homeostasis. The time course of DCF-induced enteropathy and the subsequent wound healing observed in our model were similar to a previous report (25). Moreover, disease induction was not adversely affected in Tg mice receiving GCV since the number of DCF-induced ulcers was identical at 18 h compared with control littermates. However, the number of ulcers recorded at 48 h was significantly higher in Tg mice, strongly indicating that EGC ablation is associated with aberrant mucosal repair. Furthermore, given that IL-1β mRNA levels were identical at 48 h in the two conditions (data not shown), changes in wound healing are probably not due to differences in inflammatory response between Tg and NTg mice. This is also consistent with an absence of inflammation observed in Tg mice after 8 days of GCV treatment (28). Finally, it is highly unlikely that the delayed mucosal healing observed in the EGC-knockout animals is due to an impaired proliferative response since we have shown that EGC negatively regulate IEC proliferation (20). These findings strongly suggest that, in vivo, EGC favor mucosal healing processes and could enhance restitution (18, 22).

We then focused on characterizing the putative direct role of EGC as an inducer of IEB wound healing. EGC-induced epithelial restitution was clearly associated with elevated IEC spreading, which was independent of cellular hypertrophy. Cellular hypertrophy is characterized by an increase in the total cellular RNA and protein content, whereas the DNA content remains unchanged. We have previously reported that RNA-to-DNA and protein-to-DNA ratios were not altered in Caco-2 cells in coculture with EGC (20). In addition, epithelial wound healing mediated by enhanced cell spreading appears to be an EGC-specific mechanism, since in our model myofibroblasts promoted epithelial restitution but not IEC spreading. EGC-induced wound repair does not involve an increase in IEC proliferation since EGC did not modify the number of IEC after 24 h of coculture (20). In addition, these results further emphasize the role of cell spreading as a cellular mechanism involved in early stages of wound repair, prior to initiation of cell proliferation and differentiation (18, 22).

A major finding of our study was the observation that EGC promote IEB restitution and cell spreading via FAK-dependent pathways. Modulation of FAK expression by EGC was also demonstrated in vivo as we showed that 1) there was a positive correlation between S-100β and FAK mRNA abundance in human colonic biopsies, and 2) EGC ablation induced a decrease in FAK mRNA abundance in GFAP-HSVtk Tg mice. However, these in vivo results are only indirect evidence and we cannot rule out that variations in FAK mRNA abundance might also result in part from altered gene expression in nonepithelial cells. The modulation of IEB restitution by EGC via FAK-dependent pathways is in agreement with studies showing that increased FAK expression in IEC is associated with enhanced epithelial restitution (14). Moreover, increased FAK expression is detected near the border of human gastric and colonic ulcers (37). In our study, EGC also increased restitution via FAK activity-dependent pathways. This result is consistent with previous reports showing that inhibition of Src-induced activation of FAK in IEC or following transfection of IEC with FRNK lead to reduced cellular motility (27, 41). The dual control of EGC on both FAK expression and phosphorylation may allow acute and chronic regulation of IEC functions. In addition to an involvement in wound healing, EGC-regulated FAK phosphorylation and expression may influence IEC anoikis, survival, and differentiation (5, 17, 42).

Another finding of our study is the identification of proEGF as a glial mediator, which is partly involved in the EGC-mediated epithelial restitution. Besides proEGF, other mediators liberated by EGC could also participate in restitution. Indeed, among known mediators secreted by EGC, TGF-β1 has clearly been demonstrated to enhance intestinal epithelial wound healing (11), and GSNO, another glial mediator, has been shown to induced wound healing in skin (2). However, the characterization of their effects in the gut merits further investigation. Nevertheless, proEGF played probably a major role in epithelial restitution induced by EGC as EGF and EGFR blocking antibodies, and an EGFR kinase inhibitor inhibited EGC-induced epithelial restitution. In support of this finding, exogenous proEGF partly reproduced EGC effects, and this growth factor was detected in EGC-CM. Although EGC have been shown to secrete various factors (20, 28), this is the first demonstration of glial proEGF secretion. Other reports have suggested that astrocytes in the CNS express and release EGF (13, 36). Although the mature 6-kDa form of EGF has been measured in the gut (15), proEGF has never been reported. In general, proEGF is intracellularly processed into mature EGF and released via exocrine secretions (16). However, in tissues such as kidney, mammary, and lacrimal glands, unprocessed proEGF is present in the cell membrane and exposed at the cell surface (16). Recent data have shown that in the kidney proEGF could be shed in a soluble form (16). In this study, we were able to detect proEGF but not the mature 6-kDa form of EGF in EGC lysates or EGC-CM. This suggests that EGC may not release mature EGF, or that it is released at levels below the detection levels of our assay. Whether proEGF itself or its mature forms are responsible for the increase in epithelial restitution induced by EGC is currently not fully determined in our study. However, proEGF can directly activate EGFR (6). The effects of proEGF could also be mediated by cleaved forms of proEGF resulting from its enzymatic processing as it has been previously shown in rat kidney (16). Such extracellular maturation of proEGF could occur 1) at the level of IEC surface via membrane-bound proteases or MMPs, or 2) in the extracellular medium via soluble proteases or MMPs secreted either by EGC or IEC. These hypotheses are reinforced in our study as an MMPs inhibitor significantly reduced EGC-CM- and proEGF-induced IEC spreading.

The EGC-induced epithelial restitution was mediated by EGFR-dependent pathways, probably resulting from EGFR activation by proEGF or its matured form as blocking antibodies to EGFR prevented the effects of EGC-CM. These results are in agreement with a major role for EGFR in intestinal epithelial wound repair processes. Indeed, activation of EGFR by its ligands leads to increased IEB wound repair and IEC spreading (23, 31, 40).

Finally, the glial secretion of proEGF, which in our study exhibited a lower wound healing ability compared with EGF at a given concentration, could have pathophysiological relevance. Indeed, when major wound healing processes are necessary, the availability of a pool of factors that can actively repair the barrier is of interest. In particular, during inflammatory or infectious insults of IEB, the EGC-derived pool of proEGF could be activated by concomitant release of MMPs or proteases, which would process proEGF into mature EGF and therefore enhance wound repair.

In summary, this study further reinforces the role of EGC as a major cellular regulator of IEB function and gut integrity. In addition, we identify proEGF as a glial mediator involved in these effects. Defects in EGC such as those recently reported in Crohn's disease (10, 34) or in necrotizing enterocolitis (39) may therefore contribute to the pathophysiology by inhibiting mucosal healing.

GRANTS

L. Van Landeghem was supported by a grant French Ministry of Education Research and Technology. M. M. Mahé is supported by a grant from Nantes Metropole. T. Savidge was funded by a grant from the Eli Broad Medical Foundation and from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases 1R21DK078032. T. Wedel was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation (DFG WE 2366/4-2). This work was supported by a grant from INCa Appel d'Offre Libre 2007 (MOPRESTAGLIA) to M. Neunlist. M. Neunlist and P. Derkinderen are recipient of a Contrat d'Interface Inserm.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr. Hervé Enslen for advice and for providing the FRNK-GFP construct, the IFR26 Imaging Facility PiCell, and especially Philippe Hulin for precious help in the video time lapse acquiring and montage. They also thank Philippe Aubert and Samuel Ardois for invaluable technical help.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 41–53, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amadeu TP, Seabra AB, de Oliveira MG, Costa AM. S-nitrosoglutathione-containing hydrogel accelerates rat cutaneous wound repair. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 21: 629–637, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aube AC, Cabarrocas J, Bauer J, Philippe D, Aubert P, Doulay F, Liblau R, Galmiche JP, Neunlist M. Changes in enteric neurone phenotype and intestinal functions in a transgenic mouse model of enteric glia disruption. Gut 55: 630–637, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blikslager AT, Moeser AJ, Gookin JL, Jones SL, Odle J. Restoration of barrier function in injured intestinal mucosa. Physiol Rev 87: 545–564, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bouchard V, Demers MJ, Thibodeau S, Laquerre V, Fujita N, Tsuruo T, Beaulieu JF, Gauthier R, Vezina A, Villeneuve L, Vachon PH. Fak/Src signaling in human intestinal epithelial cell survival and anoikis: differentiation state-specific uncoupling with the PI3-K/Akt-1 and MEK/Erk pathways. J Cell Physiol 212: 717–728, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Breyer JA, Cohen S. The epidermal growth factor precursor isolated from murine kidney membranes. Chemical characterization and biological properties. J Biol Chem 265: 16564–16570, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bush TG, Savidge TC, Freeman TC, Cox HJ, Campbell EA, Mucke L, Johnson MH, Sofroniew MV. Fulminant jejuno-ileitis following ablation of enteric glia in adult transgenic mice. Cell 93: 189–201, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chevalier J, Derkinderen P, Gomes P, Thinard R, Naveilhan P, Vanden Berghe P, Neunlist M. Activity-dependent regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase expression in the enteric nervous system. J Physiol 586: 1963–1975, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Conlin VS, Wu X, Nguyen C, Dai C, Vallance BA, Buchan AM, Boyer L, Jacobson K. Vasoactive intestinal peptide ameliorates intestinal barrier disruption associated with Citrobacter rodentium-induced colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 297: G735–G750, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cornet A, Savidge TC, Cabarrocas J, Deng WL, Colombel JF, Lassmann H, Desreumaux P, Liblau RS. Enterocolitis induced by autoimmune targeting of enteric glial cells: a possible mechanism in Crohn's disease? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 13306–13311, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dignass AU, Tsunekawa S, Podolsky DK. Fibroblast growth factors modulate intestinal epithelial cell growth and migration. Gastroenterology 106: 1254–1262, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Froslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology 133: 412–422, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gomes FC, Maia CG, de Menezes JR, Neto VM. Cerebellar astrocytes treated by thyroid hormone modulate neuronal proliferation. Glia 25: 247–255, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hines OJ, Ryder N, Chu J, McFadden D. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates intestinal restitution via cytoskeletal activation and remodeling. J Surg Res 92: 23–28, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kasselberg AG, Orth DN, Gray ME, Stahlman MT. Immunocytochemical localization of human epidermal growth factor/urogastrone in several human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem 33: 315–322, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Le Gall SM, Meneton P, Mauduit P, Dreux C. The sequential cleavage of membrane anchored pro-EGF requires a membrane serine protease other than kallikrein in rat kidney. Regul Pept 122: 119–129, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levy P, Robin H, Kornprobst M, Capeau J, Cherqui G. Enterocytic differentiation of the human Caco-2 cell line correlates with alterations in integrin signaling. J Cell Physiol 177: 618–627, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mammen JM, Matthews JB. Mucosal repair in the gastrointestinal tract. Crit Care Med 31: S532–S537, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mitra SK, Hanson DA, Schlaepfer DD. Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 56–68, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Neunlist M, Aubert P, Bonnaud S, Van Landeghem L, Coron E, Wedel T, Naveilhan P, Ruhl A, Lardeux B, Savidge T, Paris F, Galmiche JP. Enteric glia inhibit intestinal epithelial cell proliferation partly through a TGF-β1-dependent pathway. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G231–G241, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Neunlist M, Toumi F, Oreschkova T, Denis M, Leborgne J, Laboisse CL, Galmiche JP, Jarry A. Human ENS regulates the intestinal epithelial barrier permeability and a tight junction-associated protein ZO-1 via VIPergic pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 285: G1028–G1036, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Okamoto R, Watanabe M. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of the epithelial repair in IBD. Dig Dis Sci 50, Suppl 1: S34–S38, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Polk DB. Epidermal growth factor receptor-stimulated intestinal epithelial cell migration requires phospholipase C activity. Gastroenterology 114: 493–502, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Powell DW, Adegboyega PA, Di Mari JF, Mifflin RC. Epithelial cells and their neighbors I. Role of intestinal myofibroblasts in development, repair, and cancer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 289: G2–G7, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ramirez-Alcantara V, Loguidice A, Boelsterli UA. Protection from diclofenac-induced small intestinal injury by the JNK inhibitor SP600125 in a mouse model of NSAID-associated enteropathy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 297: G990–G998, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ruhl A, Nasser Y, Sharkey KA. Enteric glia. Neurogastroenterol Motil 16, Suppl 1: 44–49, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sanders MA, Basson MD. Collagen IV regulates Caco-2 migration and ERK activation via α1β1- and α2β1-integrin-dependent Src kinase activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 286: G547–G557, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Savidge TC, Newman P, Pothoulakis C, Ruhl A, Neunlist M, Bourreille A, Hurst R, Sofroniew MV. Enteric glia regulate intestinal barrier function and inflammation via release of S-nitrosoglutathione. Gastroenterology 132: 1344–1358, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Savidge TC, Sofroniew MV, Neunlist M. Starring roles for astroglia in barrier pathologies of gut and brain. Lab Invest 87: 731–736, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sturm A, Dignass AU. Epithelial restitution and wound healing in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 14: 348–353, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tetreault MP, Chailler P, Beaulieu JF, Rivard N, Menard D. Specific signaling cascades involved in cell spreading during healing of micro-wounded gastric epithelial monolayers. J Cell Biochem 105: 1240–1209, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tillinger W, McCole DF, Keely SJ, Bertelsen LS, Wolf PL, Junger WG, Barrett KE. Hypertonic saline reduces neutrophil-epithelial interactions in vitro and gut tissue damage in a mouse model of colitis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1839–R1845, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Toumi F, Neunlist M, Cassagnau E, Parois S, Laboisse CL, Galmiche JP, Jarry A. Human submucosal neurones regulate intestinal epithelial cell proliferation: evidence from a novel co-culture model. Neurogastroenterol Motil 15: 239–242, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Villanacci V, Bassotti G, Nascimbeni R, Antonelli E, Cadei M, Fisogni S, Salerni B, Geboes K. Enteric nervous system abnormalities in inflammatory bowel diseases. Neurogastroenterol Motil 20: 1009–1016, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Von Boyen GB, Steinkamp M, Geerling I, Reinshagen M, Schafer KH, Adler G, Kirsch J. Proinflammatory cytokines induce neurotrophic factor expression in enteric glia: a key to the regulation of epithelial apoptosis in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 12: 346–354, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wagner B, Natarajan A, Grunaug S, Kroismayr R, Wagner EF, Sibilia M. Neuronal survival depends on EGFR signaling in cortical but not midbrain astrocytes. EMBO J 25: 752–762, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Walsh MF, Ampasala DR, Hatfield J, Vander Heide R, Suer S, Rishi AK, Basson MD. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates intestinal epithelial focal adhesion kinase synthesis via Smad- and p38-dependent mechanisms. Am J Pathol 173: 385–399, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Watson AJ, Duckworth CA, Guan Y, Montrose MH. Mechanisms of epithelial cell shedding in the mammalian intestine and maintenance of barrier function. Ann NY Acad Sci 1165: 135–142, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wedel T, Krammer HJ, Kuhnel W, Sigge W. Alterations of the enteric nervous system in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis revealed by whole-mount immunohistochemistry. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med 18: 57–70, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilson AJ, Gibson PR. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor in basal and stimulated colonic epithelial cell migration in vitro. Exp Cell Res 250: 187–196, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yu CF, Sanders MA, Basson MD. Human Caco-2 motility redistributes FAK and paxillin and activates p38 MAPK in a matrix-dependent manner. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 278: G952–G966, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang HM, Keledjian KM, Rao JN, Zou T, Liu L, Marasa BS, Wang SR, Ru L, Strauch ED, Wang JY. Induced focal adhesion kinase expression suppresses apoptosis by activating NF-κB signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C1310–C1320, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.