Abstract

Women are exposed to estrogen in several forms, such as oral contraceptive pills and hormone replacement therapy. Although estrogen was believed to be cardioprotective, lately, its beneficial effects are being questioned. Recent studies indicate that oxidative stress in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) may play a role in the development of hypertension. Therefore, we hypothesized that chronic exposure to low levels of estradiol-17β (E2) leads to hypertension in adult-cycling female Sprague Dawley (SD) rats potentially through generation of superoxide in the RVLM. To test this hypothesis, young adult (3 or 4 mo old) female SD rats were either sham-implanted or implanted (subcutaneously) with slow-release E2 pellets (20 ng/day) for 90 days. A group of control and E2-treated animals were fed lab chow or chow containing resveratrol (0.84 g/kg of chow), an antioxidant. Rats were implanted with telemeters to continuously monitor blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR). At the end of treatment, the RVLM was isolated for measurements of superoxide. E2 treatment significantly increased mean arterial pressure (mmHg) and HR (beats/min) compared with sham rats (119.6 ± 0.8 vs. 105.1 ± 0.7 mmHg and 371.7 ± 1.5 vs. 354.4 ± 1.3 beats/min, respectively; P < 0.0001). Diastolic and systolic BP were significantly increased in E2-treated rats compared with control animals. Superoxide levels in the RVLM increased significantly in the E2-treated group (0.833 ± 0.11 nmol/min·mg) compared with control (0.532 ± 0.04 nmol/min·mg; P < 0.05). Treatment with resveratrol reversed the E2-induced increases in BP and superoxide levels in the RVLM. In conclusion, these findings support the hypothesis that chronic exposure to low levels of E2 induces hypertension and increases superoxide levels in the RVLM and that this effect can be reversed by resveratrol treatment.

Keywords: oxidative stress, blood pressure, estrogen, brain stem

cardiovascular disease remains one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in women. Postmenopausal increases in blood pressure (BP) in women make hypertension more prevalent in women compared with men of the same age (6, 42). Because premenopausal women have lower blood pressure compared with age-matched men, estrogens were thought to play a protective role against hypertension. Estrogens are reported to improve lipid profile (52), decrease vascular resistance (28), and modulate the activity of brain nuclei involved in cardiovascular regulation (18, 47). However, recent reports from the Women's Health Initiative study, National Institutes of Health have provided evidence that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) using estrogen alone or a combination of estrogen and progestin does not confer cardiovascular protection and may actually increase the risk for coronary heart disease among postmenopausal women (30). These clinical studies have brought to light the importance of clinical and basic research in understanding the role of estrogen in BP regulation (57). Oral estrogen administration, either given alone or in combination with progestins, was found to promote systolic blood pressure in postmenopausal women (34, 46). Although the magnitude of the increase in BP was only between 1 and 2 mmHg, similar increases in systolic BP and pulse pressure are known to be associated with a higher rate of progression of coronary atherosclerosis (35) and development of cardiovascular events (34) in large clinical trials.

In addition to women who are on HRT, younger women who take oral contraceptives are also at increased risk for potentially developing cardiovascular disorders. Oral contraceptives have been used worldwide for more than 30 years. Most women taking oral contraceptives have been found to have small elevations in BP of ∼2 mm of Hg (56). In addition, ∼5% of patients who take a preparation containing more than 50 μg of estradiol-17β (E2) have significant elevations in BP greater than 140/90 mmHg (56). Estrogen rather than progesterone, appears to be the primary cause for increases in BP observed with oral contraceptives because women taking progestin-only contraceptives do not have significant elevations in BP (21). Therefore, it is important to elucidate the mechanisms by which chronic exposure to E2 increases BP.

The central nervous system plays an important role in the development and maintenance of hypertension (4, 9, 25, 26). The cortex, limbic system, hypothalamus, brain stem, and the autonomic nervous system are all known to be involved in the maintenance of BP. In the brain stem, the rostral ventral lateral medulla (RVLM) is a critical area involved in the regulation of sympathetic activity and BP. The RVLM integrates sympathetic outflow and provides excitatory input to preganglionic sympathetic cells in the spinal cord (51). The RVLM maintains basal vasomotor tone, and an increase in RVLM activity is associated with hypertension and heart failure (26). Recently, oxidative stress in the RVLM has been suggested to increase sympathetic nervous system activity and BP in several animal models of hypertension (4, 9, 25). Therefore, we hypothesized that E2-induced increase in blood pressure could be mediated by oxidative stress-related changes in RVLM.

To test this idea, young, adult cycling female Sprague-Dawley rats were exposed to low levels of E2 on a chronic basis. We attempted to reduce oxidative stress in these animals by treating them with resveratrol, an antioxidant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals and treatment.

All of the protocols followed in this experiment were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Michigan State University. Adult (3–4 mo old) female Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) were housed in temperature (23 ± 2°C)- and light-controlled (14:10-h light-dark cycle) rooms with ad libitum food and water. Estrous cycles were monitored, as described previously (22) for 2 wk, and animals that were cycling regularly were used in the experiments. In experiment 1, animals were divided into two groups (n = 4/group); sham-implanted (control); or implanted with E2 (20 ng/day, 90-day slow-release pellet; Innovative Research America, Sarasota, FL). After 60 days, sham and E2-treated rats were implanted with radiotelemetry transmitters to monitor BP, as described below. After 90 days of exposure to E2, all of the animals were killed at noon on the day of estrus. Most of the E2-treated animals were in persistent estrus after 90 days of treatment. The control animals were killed on the day of estrus after 90 days of sham implantation for comparison to the treatment group. The brains and brain stem were removed, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −70°C. The trunk blood was collected, and serum was separated and stored at −70°C until processed.

In experiment 2, animals were divided into four groups (n = 6/group): sham-implanted (control); implanted with E2 slow-release pellets (E-90; 20 ng/day for 90 days) (22); control fed with chow containing 0.84 g resveratrol/kg of chow (Res) (3); and E2-implanted rats fed with chow containing resveratrol (Res+E-90). Resveratrol treatment was started 7 wk after pellet implantation. Animals were implanted with telemeters on the 9th wk, as described below. Food intake, water intake, and body weight were monitored weekly throughout the experimental period. The animals were killed at the end of 90 days, while in the state of estrus.

BP measurement.

In the 9th wk of the treatment period, radio-telemetry transmitters (model TA11-PA-C40; Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) were implanted, as described previously (24). Briefly, the tip of the transmitter catheter was placed in the abdominal aorta through the femoral artery under general anesthesia. The body of the transmitter was placed in a subcutaneous pocket in the abdomen. Ten days later, BP data from the transmitter were collected continuously for 11 days in experiment 1, and 14 days in experiment 2 (24 h/day; 10-s averages collected every 10 min). Data were stored and analyzed using the Dataquest A.R.T. software (Data Sciences International, St. Paul, Minnesota).

Brain microdissection.

Palkovits's microdissection procedure (32) was used to isolate the RVLM. Briefly, 300-μm serial sections of brain stem were obtained using a cryostat (Slee Mainz, London, UK). The sections were transferred to microscope slides and placed on a cold stage maintained at −10°C. The RVLM of the brain stem was microdissected from sections obtained 12.00 mm to 12.48 mm posterior to the bregma using a 500-μm-diameter punch, using the rat brain stereotaxic atlas as a reference (41). The punches were stored immediately at −70°C until processed for superoxide measurement.

Superoxide measurement.

Superoxide (O2−) levels from the RVLM region were measured using a lucigenin O2− chemiluminescence assay adapted from Rey et al. (43). RVLM punches were placed in HEPES buffer (in mmol): 119 NaCl, 20 HEPES, 4.6 KCl, 1.0 MgSO4, 0.15 Na2HPO4, 0.4 KH2PO4, 5 NaHCO3, 1.2 CaCl2, 5.5 glucose (pH 7.4)]. Diethyldithiocarbamate (DDC; a superoxide dismutase inhibitor; 10 mmol) was added and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Lucigenin (5 μmol/l) was added, and the samples were incubated for 10 min at 37°C. Chemiluminescence measurements were obtained using a model TD 20/20 Luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA) for 10 readings (30 s/reading). Tiron (10 mmol/l; an O2− scavenger; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added and incubated for 15 min at 37°C, and 10 additional readings were taken. The relative amount of O2− was determined by taking the average of 2nd–9th readings prior to the addition of tiron, and subtracting the average of the 7th–10th readings after the addition of tiron. O2− generated was reported as change in chemiluminescence per minute per milligram tissue weight.

Serum estradiol.

Estradiol levels in serum separated from trunk blood were measured by double antibody radioimmunoassay by Dr. A. F. Parlow, National Hormone and Pituitary Program, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Samples were assayed in duplicate.

Statistics.

Daily BP measurements and weekly food intake, water intake, and body weight were analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA followed by post hoc Fischer's LSD test. Average BP parameters, serum estradiol and O2− data were analyzed by ANOVA, followed by post hoc Fischer's LSD test. Results were considered significant when P < 0.05. Average food intake, water intake, body weight, and heart-body weight ratio were analyzed by ANOVA followed by post hoc Fisher's LSD test. Results were considered significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Chronic exposure to estradiol-17β (E2) causes hypertension.

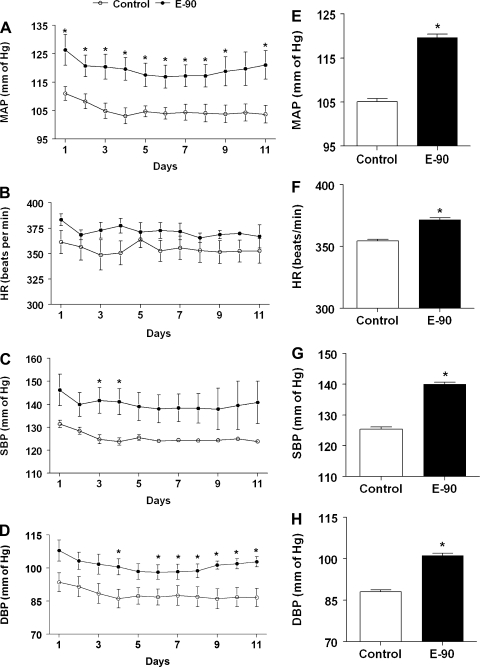

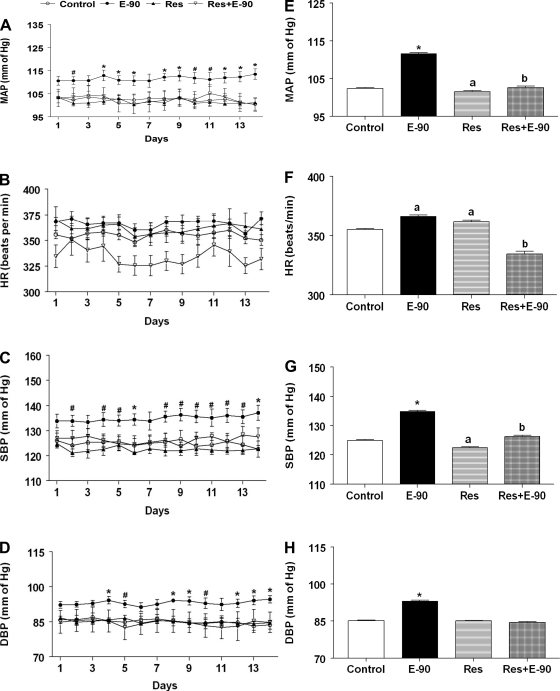

The daily average profiles and the average mean arterial pressure (MAP), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and heart rate (HR) during the 10–11th wk of treatment in control and E2-treated rats are shown in Fig. 1. As seen in Fig. 1A, the MAP in control animals remained steady over the entire period of observation. In contrast, E2 treatment increased MAP significantly (P < 0.01; Fig. 1A). The average MAP (means ± SE) measured during the 10–11th wk of observation in control rats was 105.1 ± 0.7 mmHg. In contrast, E2 exposure increased MAP significantly to 119.6 ± 0.8 (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1E). The HR profile of E2-treated rats had a tendency to increase compared with control rats during the entire period of observation (Fig. 1B). The average HR (means ± SE, beats/min; Fig. 1F) during the 10–11th wk of treatment in E2-treated rats (371.7 ± 1.5) was significantly elevated compared with control rats (354.5 ± 1.4; P < 0.0001). Similarly, the SBP and DBP profiles in E2-treated rats were significantly elevated in E2-treated rats compared with control rats (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1, C and D). E2 exposure also increased the average SBP and DBP (means ± SE; 140.0 ± 0.7 and 101.1 ± 0.8 mmHg, respectively) significantly compared with control rats (125.4 ± 0.7 and 88.0 ± 0.7 mmHg, respectively; P < 0.0001; Fig. 1, G and H).

Fig. 1.

Effect of chronic E2 exposure on blood pressure parameters. Line graphs depicting mean arterial pressure (MAP; mmHg) (A), heart rate (HR; beats/min) (B), systolic blood pressure (SBP) (C), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP; mmHg) (D), respectively. Solid circles (●) represent E2 pellet implanted (20 ng/day, 90-day slow-release pellets), and open circles (○) represent control rats. E–H: bar graphs showing the average values of the BP parameters shown in A–D, between E2-implanted and control rats. *Significant difference (P < 0.05) from control rats.

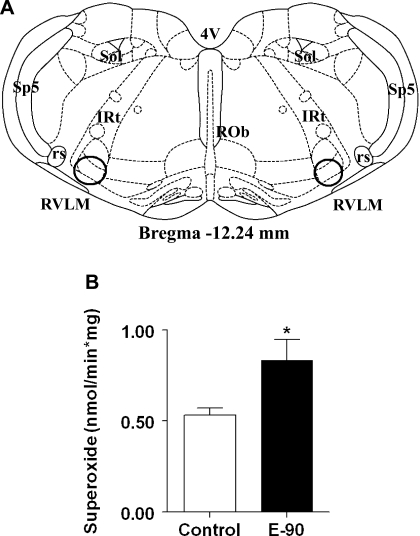

Chronic exposure to E2 increases O2− levels in RVLM.

Chronic E2 exposure significantly elevated O2− levels (means ± SE) in the RVLM of E2-treated rats (0.833 ± 0.1 nmol/min·mg) compared with control rats (0.532 ± 0.04 nmol/min·mg; P < 0.01) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of chronic E2 exposure on superoxide in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM). A: schematic coronal brain stem section showing the location of micropunches of RVLM (within circles) taken from Paxinos and Watson rat brain atlas, 6th ed. The section coordinate (−12.24-mm bregma) represents the distance caudal to the bregma. ROb, raphe obscurus nucleus; rs, rubrospinal tract; sp5, spinal trigeminal tract; IRt, intermediate reticular nucleus; Sol, nucleus of the solitary tract. B: bar graph denoting O2− levels measured in RVLM brain stem punches of E2-treated (20 ng/day, 90-day slow-release pellets) and sham-implanted female Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (n = 4 per group) using a luminometer. *Significant difference (P < 0.05) from control rats.

Chronic E2 exposure increases food intake, water intake and body weight.

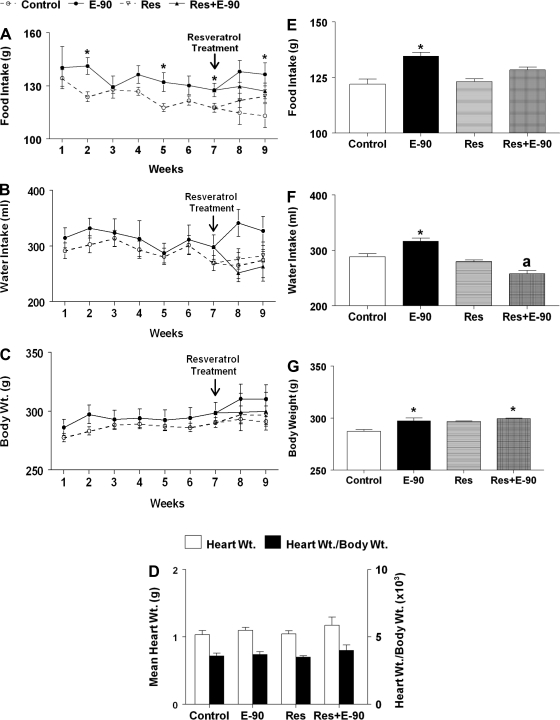

The average weekly food intake (g/wk; means ± SE), water intake (ml/wk; means ± SE), and body weight (g; means ± SE) of control, E2, resveratrol, resveratrol+E2 animals is shown in Fig. 3. There was no difference in food intake between control and E2-treated groups at the beginning of the experiment. However, food intake in the E2-treated group appeared to increase on the 2nd wk (141.7 ± 4.7 g/wk), the 5th wk (132.1 ± 5.3 g/wk), and the 7th wk (127.6 ± 3.8 g/wk) compared with control rats (123.8 ± 2.8 g/wk, 117.7 ± 2.3 g/wk, and 117.6 ± 2.5 g/wk, respectively; P < 0.05). The average food intake was significantly higher in E2-treated rats (134.6 ± 1.7 g/wk) compared with control rats (122 ± 2.3 g/wk) and those treated with resveratrol alone (123.1 ± 1.3 g/wk; P < 0.05; Fig. 3E). Feeding chow containing resveratrol did not affect food intake in the control and E2-treated groups.

Fig. 3.

Effect of chronic E2 exposure and resveratrol on food intake, water intake, body weight, and heart weight. A–C: line graphs showing food intake (g), water intake (ml), and body weight (g) between different groups of female SD rats (n = 6 per group); open circles (○) shows control, solid circle (●) shows E2 pellet implanted (E-90), open inverted triangle (▿) shows resveratrol (Res) treatment alone, and closed triangle shows resveratrol treatment on E2-implanted rats (Res+E-90). *Significant difference from control (P < 0.05). D: bar graphs showing the average values of heart weight (g) and heart-to-body weight ratio in the different treatment groups (n = 6 per group). E–G: bar graphs showing the average values of food intake, water intake, and body weight shown in A–C, respectively. E: *Significant difference (P < 0.05) from control and resveratrol-treated groups. F: *Significant difference (P < 0.005) from the rest of the groups; “a” denotes significant difference from control (P < 0.05). G: *Significant difference (P < 0.05) from control.

The average weekly water intake in control and experimental animals is given in Fig. 3B. There was a tendency for increased water intake in E2-treated rats compared with control rats in the 1st wk, and this trend continued throughout the period of observation, though the change was not statistically significant. However, the average water intake (Fig. 3F) was significantly higher in the E2-treated group (316.5 ± 5.6 ml/wk) compared with control rats (288.2 ± 5.5 ml/wk), sham-implanted resveratrol-treated group (279.6 ± 2.9 ml/wk) and the resveratrol and E2-treated group (257.5 ± 5.8 ml/wk; P < 0.005). The E2-treated group fed chow containing resveratrol consumed less water (257.5 ± 5.8 ml/wk) compared with the control group (288.2 ± 5.5 ml/wk; P < 0.05).

Changes in weekly body weight among the different groups are shown in Fig. 3C. There was no difference in body weight between the treatment groups at the beginning of the experiment. Although there was a tendency for body weight to increase with time, the average weekly body weight in the E2 group was not statistically different from that of control rats. Feeding control and E2 rats with chow containing resveratrol for 2 wk did not produce any change in body weight. The average body weight over the entire period of observation (Fig. 3G) was significantly higher in the E2 group (297.4 ± 2.7 g) compared with control rats (287.3 ± 1.6 g; P < 0.005). Feeding resveratrol did not alter the average body weight in control and E2-treated rats. Body weight in E2-treated rats fed chow containing resveratrol (299.6 ± 0.4 g) was significantly higher compared with control (P < 0.05).

There were no significant changes in heart weight or the ratio of heart weight to body weight in any of the treated groups compared with the control group (Fig. 3D).

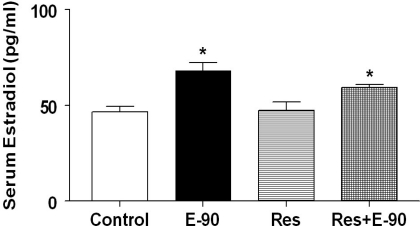

Serum E2.

Serum E2 levels (means ± SE) at the end of 90 days of E2 exposure and resveratrol treatment are shown in Fig. 4. Exposure to E2 resulted in significant increases in serum E2 of animals that are treated with E2 alone (68.2 ± 4.07 pg/ml) or treated with E2 and resveratrol (59.4 ± 1.5 pg/ml) compared with control rats (46.7 ± 2.9 pg/ml) or rats treated with resveratrol alone (47.4 ± 4.4 pg/ml, P < 0.0005). There was no difference in E2 levels between the E2-treated groups (with or without resveratrol).

Fig. 4.

Serum E2 levels. Bar graphs showing serum E2 levels in all the groups (n = 5–7 per group). *Significant difference (P < 0.05) from control and the group treated with resveratrol alone.

Resveratrol reverses chronic E2-induced hypertension.

The daily average profiles and the average MAP, SBP, DBP, and HR during the entire period of observation in control, E2, resveratrol and resveratrol + E2-treated rats are shown in Fig. 5. Similar to what was observed in Fig. 1, exposure to E2 for 90 days significantly elevated MAP, HR, SBP, and DBP compared with control rats. Feeding chow containing resveratrol to sham-implanted control rats did not alter MAP, HR, SBP, and DBP. In contrast, feeding chow containing resveratrol to E-90 rats completely reversed E2-induced increase in MAP, HR, SBP, and DBP in E2-implanted rats (P < 0.01).

Fig. 5.

Effect of resveratrol on chronic E2-induced hypertension. A–D: line graphs depicting MAP (mmHg), HR (beats/min), SBP and DBP (mmHg), respectively. Solid circles (●) represent E2 pellet implanted (20 ng/day, 90-day slow-release pellets), and open circles (○) represent control female SD rats, solid triangles (▴) represent rats fed with chow containing 0.84 g/kg resveratrol only, and open inverted triangles (▿) represent E2 pellet-implanted (20 ng/day, 90-day slow-release pellets) rats fed with chow containing 0.84 g/kg resveratrol. #Significant difference from control. *Significant difference from all the other groups. E–H: bar graphs showing the average values of the BP parameters shown in A–D. *Significant difference (P < 0.05) from all the other groups, “a” represents significant difference from control and Res+E-90, and “b” represents significant difference from control.

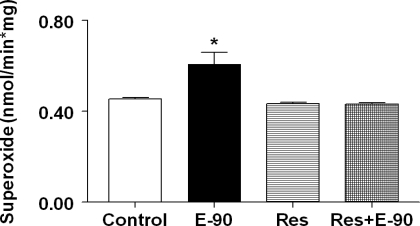

Resveratrol attenuates oxidative stress in RVLM.

Changes in superoxide levels (means ± SE, nmol/min·mg) in the RVLM of control, E2, resveratrol and resveratrol+E2 groups are shown in Fig. 6. As seen in Fig. 2, superoxide levels increased significantly in E-90 rats (0.608 ± 0.052 nmol/min·mg) compared with control rats (0.454 ± 0.007 nmol/min·mg; P < 0.005). When sham-implanted control rats were fed chow containing resveratrol alone, it did not alter superoxide levels (0.431 ± 0.007 nmol/min·mg) compared with control rats (0.454 ± 0.007 nmol/min·mg). In contrast, feeding E2-treated rats with chow containing resveratrol completely reversed E2-induced increase in superoxide levels in the RVLM (0.431 ± 0.007 vs. 0.608 ± 0.052 nmol/min·mg; P < 0.0005).

Fig. 6.

Effect of resveratrol on chronic E2-induced oxidative stress in RVLM. Bar graph showing superoxide levels measured in RVLM punches from control, E2 treated (20 ng/day, 90-day slow-release pellets), rats fed with chow containing 0.84 g/kg resveratrol only, and rats implanted with E2 pellet (20 ng/day, 90-day slow-release pellets) fed with chow containing 0.84 g/kg resveratrol (n = 4–6 per group). *Significant difference (P < 0.05) from all the other groups.

DISCUSSION

The results from the present study provide evidence that chronic exposure to low levels of E2 for 3 mo increases superoxide levels in RVLM and results in hypertension. Treatment with an antioxidant, resveratrol, reversed E2-induced increases in superoxide levels in the RVLM and reversed the increase in BP, indicating that chronic exposure to low levels of E2 is capable of causing hypertension, possibly by increasing superoxide generation in the RVLM.

Estrogen was originally believed to prevent hypertension based on the observation that postmenopausal women have a higher incidence of hypertension compared with age-matched men (17, 31, 40), and, therefore, HRT containing estrogenic preparations were believed to reduce BP in these women (48). Several possible mechanisms by which estrogens could decrease BP have been suggested. There is evidence that estrogen increases ACh-induced, nitric oxide-mediated relaxation of aorta in male spontaneously hypertensive rats (23) through upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (20). Also, estrogen is believed to act on some brain stem autonomic centers to decrease sympathetic nervous activity (54, 55), thereby causing reduced vasomotor tone and lowered BP.

Contrary to the belief that estrogens can lower BP, there is a large body of evidence, indicating that repeated exposure to low levels of estrogens, as in the case of oral contraceptives, can cause an increase in BP. Numerous human clinical studies have associated chronic use of contraceptive pills with increase in BP (12, 29, 56). Similar results have been seen in animal studies, where exposure to a combination of 1 μg of ethinyl estradiol and 10 μg of norgestrel or ethinylestradiol alone for 10 wk resulted in concomitant increases in systolic and mean arterial BP (7, 36, 38). In another study, female SD rats injected with 0.2 μg of ethinyl estradiol exhibited significant increases in systolic BP of 17 mmHg in 6 wk and 32 mmHg in 12 wk (7). Different mechanisms have been proposed for oral contraceptive-induced hypertension. These include impaired renal handling of water resulting in volume-dependent hypertension (37) and hyperactivity of the renin-angiotensin system (7, 38). Increased water intake as observed in the present study could be another contributing factor to volume expansion. However, it is not clear whether this is associated with the increased food intake and body weight observed in E2-treated animals. Interestingly, there were no measureable increases in heart weight, or the ratio of heart weight to body weight, in E2-treated rats. This is perhaps due to the rather mild increase in BP caused by E2 and to the known protective effect of E2 against pressure-induced cardiac hypertrophy (50).

The increase in MAP, HR, SBP, and DBP with chronic E2 exposure that was observed in the present study is supported by other reports (7, 36, 38). The main difference between these and the present study is the dose of E2 used and duration of exposure. Although the doses used in other studies ranged from 0.2 to 10 μg of various estrogenic preparations, we were able to observe increases in cardiovascular parameters with 10-fold less concentration of E2 (0.02 μg or 20 ng). In contrast to our present study, Brosnihan et al. (5), have shown that 3 wk of estrogen treatment decreased MAP and significantly decreased ANG-II-induced pressor response in female ovariectomized rats, which was accompanied by significant reduction in plasma ANG II levels (5). However, the dose of E2 used in their study was 1.5 mg/day, which yielded plasma concentrations of 190 ± 20 pg/ml. With a similar dosage of E2, Gimenez et al. (16) demonstrated enhanced hypotensive responses to administration of an ACE inhibitor in E2-treated 18-mo-old female SHR rats (16). When using 1.5 mg/day, the serum E2 concentrations were ∼2.5 fold higher than those that have been found in the present study, where serum E2 concentrations were 68.2 ± 4.07 pg/ml in animals that were treated with E2 alone. Previous studies also used a much shorter E2 exposure time frame than those used in the present study, thus complicating the comparisons. In the present study, we monitored changes in BP only 9 wk after E2 implantation. Further studies are needed to determine exactly when the changes in BP become apparent in these animals.

The mechanism by which exposure to low doses of E2 induces hypertension is not clear. Several brain sites, such as the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, the subfornical organ, nucleus tractus solitarius, and the RVLM are known to be involved in the regulation of blood pressure (8). We chose to focus specifically on the RVLM because it is known to be involved in the maintenance of basal vasomotor tone via regulation of sympathetic activity (45). Moreover, brain stem neurons in the RVLM contain estrogen receptor mRNA (1, 27, 49), indicating that this is a potential site of E2 action. Also, stimulation of the RVLM is known to activate sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the intermediolateral cell column of the spinal cord and increase sympathetic activity resulting in hypertension (14). An E2-induced increase in O2− levels in the RVLM observed in the present study may act through similar mechanisms. Other studies have shown an association between O2− in the RVLM and hypertension in multiple animal models (9, 19, 25, 39). Moreover, reversal of hypertension by increasing the expression of superoxide dismutase using gene transfer and adenoviral vectors or decreasing O2− in the RVLM substantiates the role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of hypertension (10, 11, 13, 15). Because our results clearly indicated that E2 treatment increases O2− production in the RVLM, we wanted to explore the possibility of reversing this effect using the antioxidant, resveratrol.

Resveratrol is a red wine polyphenol, which is known to possess antioxidant and O2−-scavenging properties (53) and exerts strong antioxidant effects in the brain (33). In the current study, treatment with resveratrol reduced MAP, HR, SBP, and DBP induced by E2 treatment with complete quenching of O2− in the RVLM. Resveratrol has been shown to reduce SBP in obese Zucker rats by increasing eNOS expression in the aorta (44). Resveratrol treatment also prevented hypertension caused by a high-fat diet in female rats (2). In the present study, treatment of E2-treated rats with resveratrol reversed E2-induced increase in O2− in the RVLM and also decreased BP, raising the possibility that E2's effects on BP could be mediated through increased production of O2−.

In conclusion, our results support the hypothesis that chronic exposure to low levels of E2 causes hypertension in young SD female rats. This hypertensive effect of E2 may be related to increased O2− production in the RVLM. Although, this study examines the effect of E2 on O2− generation in the RVLM, the involvement of other brain sites and peripheral tissues, such as the vasculature and kidney, should also be considered. Collectively, this study provides valuable insights into the mechanisms by which chronic low-dose exposure to E2 causes hypertension and draws attention to potential cardiovascular risks faced by women on long-term oral contraceptives.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AG027697, Michigan Agricultural Experiment Station, Companion Animal Fund, College of Veterinary Medicine, Michigan State University and the Pearl J. Aldrich Endowment in Aging-Related Research.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ms. Katrina Linning for her technical help and Dr. A. F. Parlow, National Hormone and Peptide Program, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases for performing the estradiol radioimmunoassay.

REFERENCES

- 1. Amandusson A, Hermanson O, Blomqvist A. Estrogen receptor-like immunoreactivity in the medullary and spinal dorsal horn of the female rat. Neurosci Lett 196: 25–28, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aubin MC, Lajoie C, Clement R, Gosselin H, Calderone A, Perrault LP. Female rats fed a high-fat diet were associated with vascular dysfunction and cardiac fibrosis in the absence of overt obesity and hyperlipidemia: therapeutic potential of resveratrol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 325: 961–968, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bottner M, Christoffel J, Jarry H, Wuttke W. Effects of long-term treatment with resveratrol and subcutaneous and oral estradiol administration on pituitary function in rats. J Endocrinol 189: 77–88, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Braga VA. Dietary salt enhances angiotensin-II-induced superoxide formation in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Auton Neurosci 155: 14–18, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brosnihan KB, Li P, Ganten D, Ferrario CM. Estrogen protects transgenic hypertensive rats by shifting the vasoconstrictor-vasodilator balance of RAS. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R1908–R1915, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, Brown C, Cutler JA, Higgins M, Horan MJ, Labarthe D. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991. Hypertension 25: 305–313, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Byrne KB, Geraghty DP, Stewart BJ, Burcher E. Effect of contraceptive steroid and enalapril treatment of systolic blood pressure and plasma renin-angiotensin in the rat. Clin Exp Hypertens 16: 627–657, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carlson SH, Wyss JM. Neurohormonal regulation of the sympathetic nervous system: new insights into central mechanisms of action. Curr Hypertens Rep 10: 233–240, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chan SH, Hsu KS, Huang CC, Wang LL, Ou CC, Chan JY. NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide anion mediates angiotensin II-induced pressor effect via activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Circ Res 97: 772–780, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chan SH, Wu KL, Chang AY, Tai MH, Chan JY. Oxidative impairment of mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes in rostral ventrolateral medulla contributes to neurogenic hypertension. Hypertension 53: 217–227, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chan SH, Wu KL, Kung PS, Chan JY. Oral intake of rosiglitazone promotes a central antihypertensive effect via upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma and alleviation of oxidative stress in rostral ventrolateral medulla of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 55: 1444–1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chasan-Taber L, Willett WC, Manson JE, Spiegelman D, Hunter DJ, Curhan G, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ. Prospective study of oral contraceptives and hypertension among women in the United States. Circulation 94: 483–489, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chu Y, Iida S, Lund DD, Weiss RM, DiBona GF, Watanabe Y, Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Gene transfer of extracellular superoxide dismutase reduces arterial pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats: role of heparin-binding domain. Circ Res 92: 461–468, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dampney RA. Functional organization of central pathways regulating the cardiovascular system. Physiol Rev 74: 323–364, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fennell JP, Brosnan MJ, Frater AJ, Hamilton CA, Alexander MY, Nicklin SA, Heistad DD, Baker AH, Dominiczak AF. Adenovirus-mediated overexpression of extracellular superoxide dismutase improves endothelial dysfunction in a rat model of hypertension. Gene Ther 9: 110–117, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gimenez J, Garcia MP, Serna M, Bonacasa B, Carbonell LF, Quesada T, Hernandez I. 17β-oestradiol enhances the acute hypotensive effect of captopril in female ovariectomized spontaneously hypertensive rats. Exp Physiol 91: 715–722, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA 290: 199–206, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. He XR, Wang W, Crofton JT, Share L. Effects of 17β-estradiol on the baroreflex control of sympathetic activity in conscious ovariectomized rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R493–R498, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hirooka Y. Role of reactive oxygen species in brainstem in neural mechanisms of hypertension. Auton Neurosci 142: 20–24, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang A, Sun D, Koller A, Kaley G. 17β-estradiol restores endothelial nitric oxide release to shear stress in arterioles of male hypertensive rats. Circulation 101: 94–100, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hussain SF. Progestogen-only pills and high blood pressure: is there an association? A literature review. Contraception 69: 89–97, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kasturi BS, MohanKumar SM, Sirivelu MP, MohanKumar PS. Chronic exposure to low levels of oestradiol-17β affects oestrous cyclicity, hypothalamic norepinephrine and serum luteinising hormone in young intact rats. J Neuroendocrinol 21: 568–577, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kauser KRG. 17β-Estradiol augments endothelial nitric oxide production in the aortae of male spontaneously hypertensive rats. In: The Biology of Nitric Oxide, edited by Moncada S, Feelisch M, Busse R, Miggs EA. London, UK: Portland Press, 1995, p. 13–18 [Google Scholar]

- 24. King AJ, Osborn JW, Fink GD. Splanchnic circulation is a critical neural target in angiotensin II salt hypertension in rats. Hypertension 50: 547–556, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kishi T, Hirooka Y, Kimura Y, Ito K, Shimokawa H, Takeshita A. Increased reactive oxygen species in rostral ventrolateral medulla contribute to neural mechanisms of hypertension in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circulation 109: 2357–2362, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kishi T, Hirooka Y, Kimura Y, Sakai K, Ito K, Shimokawa H, Takeshita A. Overexpression of eNOS in RVLM improves impaired baroreflex control of heart rate in SHRSP. Rostral ventrolateral medulla Stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 41: 255–260, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Laflamme N, Nappi RE, Drolet G, Labrie C, Rivest S. Expression and neuropeptidergic characterization of estrogen receptors (ERα and β) throughout the rat brain: anatomical evidence of distinct roles of each subtype. J Neurobiol 36: 357–378, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lieberman EH, Gerhard MD, Uehata A, Walsh BW, Selwyn AP, Ganz P, Yeung AC, Creager MA. Estrogen improves endothelium-dependent, flow-mediated vasodilation in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med 121: 936–941, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lim KG, Isles CG, Hodsman GP, Lever AF, Robertson JW. Malignant hypertension in women of childbearing age and its relation to the contraceptive pill. Br Med J 294: 1057–1059, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Manson JE, Hsia J, Johnson KC, Rossouw JE, Assaf AR, Lasser NL, Trevisan M, Black HR, Heckbert SR, Detrano R, Strickland OL, Wong ND, Crouse JR, Stein E, Cushman M. Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 349: 523–534, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mercuro G, Zoncu S, Saiu F, Mascia M, Melis GB, Rosano GM. Menopause induced by oophorectomy reveals a role of ovarian estrogen on the maintenance of pressure homeostasis. Maturitas 47: 131–138, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. MohanKumar SM, MohanKumar PS, Quadri SK. Specificity of interleukin-1beta-induced changes in monoamine concentrations in hypothalamic nuclei: blockade by interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Brain Res Bull 47: 29–34, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mokni M, Elkahoui S, Limam F, Amri M, Aouani E. Effect of resveratrol on antioxidant enzyme activities in the brain of healthy rat. Neurochem Res 32: 981–987, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nair GV, Chaput LA, Vittinghoff E, Herrington DM. Pulse pressure and cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women with coronary heart disease. Chest 127: 1498–1506, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nair GV, Waters D, Rogers W, Kowalchuk GJ, Stuckey TD, Herrington DM. Pulse pressure and coronary atherosclerosis progression in postmenopausal women. Hypertension 45: 53–57, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Olatunji LA, Soladoye AO. The effect of nifedipine on oral contraceptive-induced hypertension in rats. Niger Postgrad Med J 13: 277–281, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Olatunji LA, Soladoye AO. High-calcium diet reduces blood pressure, blood volume and preserves vasorelaxation in oral contraceptive-treated female rats. Vascul Pharmacol 52: 95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Olatunji LA, Soladoye AO. Oral contraceptive-induced high blood pressure is prevented by renin-angiotensin suppression in female rats but not by sympathetic nervous system blockade. Indian J Exp Biol 46: 749–754, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Oliveira-Sales EB, Nishi EE, Carillo BA, Boim MA, Dolnikoff MS, Bergamaschi CT, Campos RR. Oxidative stress in the sympathetic premotor neurons contributes to sympathetic activation in renovascular hypertension. Am J Hypertens 22: 484–492, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Owens JF, Stoney CM, Matthews KA. Menopausal status influences ambulatory blood pressure levels and blood pressure changes during mental stress. Circulation 88: 2794–2802, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. New York: Academic Press, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reckelhoff JF. Gender differences in the regulation of blood pressure. Hypertension 37: 1199–1208, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rey FE, Li XC, Carretero OA, Garvin JL, Pagano PJ. Perivascular superoxide anion contributes to impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation: role of gp91(phox). Circulation 106: 2497–2502, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rivera L, Moron R, Zarzuelo A, Galisteo M. Long-term resveratrol administration reduces metabolic disturbances and lowers blood pressure in obese Zucker rats. Biochem Pharmacol 77: 1053–1063, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ross CA, Ruggiero DA, Park DH, Joh TH, Sved AF, Fernandez-Pardal J, Saavedra JM, Reis DJ. Tonic vasomotor control by the rostral ventrolateral medulla: effect of electrical or chemical stimulation of the area containing C1 adrenaline neurons on arterial pressure, heart rate, and plasma catecholamines and vasopressin. J Neurosci 4: 474–494, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288: 321–333, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Saleh MC, Connell BJ, Saleh TM. Estrogen may contribute to ischemic tolerance through modulation of cellular stress-related proteins. Neurosci Res 63: 273–279, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Seely EW, Walsh BW, Gerhard MD, Williams GH. Estradiol with or without progesterone and ambulatory blood pressure in postmenopausal women. Hypertension 33: 1190–1194, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shughrue PJ, Lane MV, Merchenthaler I. Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta mRNA in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol 388: 507–525, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Skavdahl M, Steenbergen C, Clark J, Myers P, Demianenko T, Mao L, Rockman HA, Korach KS, Murphy E. Estrogen receptor-beta mediates male-female differences in the development of pressure overload hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H469–H476, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sved AF, Ito S, Madden CJ, Stocker SD, Yajima Y. Excitatory inputs to the RVLM in the context of the baroreceptor reflex. Annals NY Acad Sci 940: 247–258, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tadmor OP, Kleinman Y, Reisin A, Livshin Y, Diamant YZ. The effects of two fixed hormonal replacement therapy protocols on blood lipid profile. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 46: 109–116, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vidavalur R, Otani H, Singal PK, Maulik N. Significance of wine and resveratrol in cardiovascular disease: French paradox revisited. Exp Clin Cardiol 11: 217–225, 2006 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vongpatanasin W, Tuncel M, Mansour Y, Arbique D, Victor RG. Transdermal estrogen replacement therapy decreases sympathetic activity in postmenopausal women. Circulation 103: 2903–2908, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Weitz G, Elam M, Born J, Fehm HL, Dodt C. Postmenopausal estrogen administration suppresses muscle sympathetic nerve activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 344–348, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Woods JW. Oral contraceptives and hypertension. Hypertension 11: II11–II15, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yanes LL, Reckelhoff JF. A new piece in the hypertension puzzle: central blood pressure regulation by sex steroids. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1583–H1584, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]