Preface

Recent advances in catalysis have made the incorporation of fluorine into complex organic molecules easier than ever before, but selective, general, and practical fluorination reactions remain sought after. Fluorination of molecules often imparts desirable properties such as metabolic and thermal stability, and fluorinated molecules are therefore frequently used as pharmaceuticals or materials. Even with the latest advances in chemistry, carbon–fluorine bond formation in complex molecules is still a significant challenge. Within the last few years, new reactions to make organofluorides have emerged and exemplify how to overcome some of the intricate challenges associated with fluorination.

Introduction

Carbon–fluorine bonds play an integral role in pharmaceuticals1,2, agrochemicals3, materials4, and tracers for positron emission tomography5. Fluorine uniquely affects the properties of organic molecules through strong polar interactions due to the atom’s high electronegativity and small size6. The introduction of fluorine into pharmaceuticals can lead to increased bioavailablity, lipophilicity, metabolic stability, and strength of protein-ligand binding interactions1. Approximately 30% of all agrochemicals and 20% of all pharmaceuticals contain fluorine1, including drugs such as Lipitor®, Lexapro®, and Prozac®. Polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon®), a perfluorinated polymer, is used every day in household cookware due to its low coefficient of friction and hydrophobicity. Perfluorinated solvents are used as unique reaction media, distinct from organic solvents and water by forming a “fluorous phase” that can be useful in applications like catalyst recovery and purification7. The non-natural isotope fluorine-18 is the most commonly used positron-emitting isotope for molecular positron emission tomography (PET) imaging in oncology, with millions of PET scans using 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) performed every year8.

Given the utility of fluorine, it is not a surprise that chemists have given the element special recognition. Yet, despite fluorine’s importance and over 100 years of organofluorine chemistry, carbon–fluorine bond formation is still challenging 9–12. Conventional fluorination reactions that have been developed in the early 20th century are generally limited to very simple molecules13. Reliable fluorination of more complex molecules at specific positions is challenging. Arguably, even Nature has not been able to develop a diverse set of fluorination reactions. Despite fluorine being the thirteenth most abundant element in the earth’s crust, only 21 biosynthesized natural molecules containing fluorine are known, compared to thousands with the heavier halogen homologs chlorine and bromine14,15. In Nature, chlorination and bromination reactions are often catalyzed by haloperoxidases, but no fluoroperoxidase is known, likely a consequence of the high oxidation potential of fluorine. Additionally, the high solvation energy of fluoride in aqueous media results in a tightly bound hydration shell of water molecules around fluoride, which lowers its nucleophilicity and therefore its reactivity. The first recognized natural fluorinating enzyme 5′-fluoro-5′-deoxyadenosine synthase likely dehydrates solvated fluoride in the active site, and thereby increases fluoride’s nucleophilicity for the ensuing substitution reaction16,17.

During the past five years, chemists have developed new methods to incorporate fluorine into organic molecules by making carbon–fluorine (C–F) and carbon–trifluoromethyl (C–CF3) bonds on both aromatic rings and aliphatic chains. The new bond-forming reactions can be efficient means to access desired organic molecules that are not readily synthesized using traditional fluorination chemistry. The development of suitable catalysts has beneficially influenced the progress of modern fluorination. In this Review, we present fundamental challenges of organofluorine chemistry and novel transition-metal-catalyzed and organocatalyzed C–F and C–CF3 bond-forming reactions.

Challenges associated with C–F bond formation

Difficulties in C–F bond formation arise from the fact that fluorine is the most oxidizing and most electronegative element (Pauling electronegativity: 4.0), and fluoride has a small ionic radius (1.33 Å18). Due to its electronegativity and anionic radius, fluoride, the most abundant form of the element on earth, can form strong hydrogen bonds with, for example, water, alcohols, amines, and amides19, and therefore is typically only weakly nucleophilic in the presence of hydrogen bond donors. Weakly nucleophilic fluoride limits access to C–F bonds via nucleophilic substitution reactions, a conventional and still common and way to make C–F bonds20. When hydrogen-bond donors are meticulously excluded, fluoride is a better nucleophile, but also basic, which can lead to undesired side reactions.

Conventional fluorination reactions that afford aromatic fluorides like the Balz-Schiemann reaction and the Halex (halogen exchange) process generally require harsh conditions and consequently have limited substrate scopes. High temperatures or highly reactive intermediates or reagents have been the only means by which to incorporate fluorine into arenes. Reactions performed in the presence of catalysts, on the other hand, can often result in milder reaction conditions by selectively reducing the activation barriers from starting material to product. Catalysis has been applied to transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions with utmost success (see Box 1). But until recently, fluorination reactions were notably absent from the metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction repertoire. Carbon–fluorine bonds are strong; in fact, no other element makes stronger single bonds to carbon than fluorine does21, and therefore, most C–F bond-forming reactions are thermodynamically feasible. A thermodynamically feasible but kinetically challenging reaction can be addressed ideally by catalysis. Conceptually, transition metal complexes have the potential to selectively reduce the barrier of activation for C–F bond formation and thus to render the thermodynamically favorable fluorination process kinetically more accessible. However, overcoming the activation barrier to C–F bond formation is challenging because metal–fluorine bonds are also strong, and thus appropriate catalysts design is difficult.

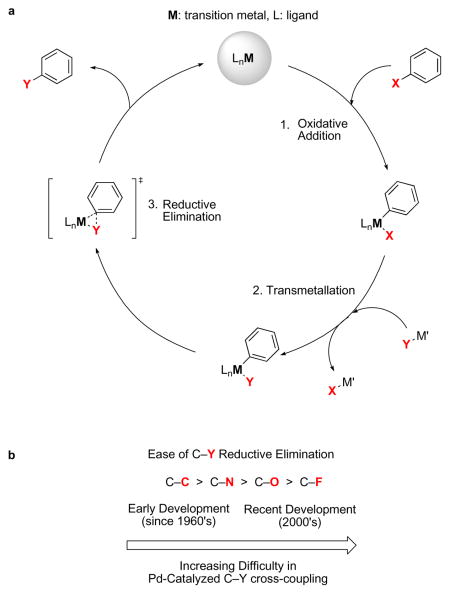

Box 1. Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions.

Metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions are reactions that join two molecular fragments using a metal as catalyst. The 2010 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to pioneers of palladium-catalyzed carbon–carbon cross-coupling reactions first disclosed over 40 years ago96. Since then, cross-coupling reactions have become a staple of modern organic synthesis and have been developed for virtually every element in the first and second row of the p-block of the periodic table97–100. Common examples of transition metals used in cross-coupling catalysis include palladium, copper, nickel, and iron. In general, when cross-coupling reactions unite two fragments, one fragment serves as the electrophile and the other fragment serves as the nucleophile. As shown in Figure 1a, the elementary organometallic chemistry steps of a catalysis cycle are: 1) Oxidative addition. A metal inserts into a σ-bond of the electrophile. This step increases the formal oxidation state of the metal and increases the number of ligands bound to the metal; 2) Transmetallation (ligand exchange). The nucleophile replaces a ligand on the metal. After transmetallation, both molecular fragments to be coupled are bound to the metal; 3) Reductive elimination, the actual bond forming event to make the organic product. Reductive elimination extrudes the new organic molecule with both molecular fragments united by a new σ-bond, leaving the metal in its original oxidation state and ready to start the catalysis cycle again. The difficulty of reductive elimination to form C–C, C–N, C–O, and C–F bonds increases across the series (Fig. 1b). This trend parallels the electronegativity of the elements as well as the metal-ligand bond strength. Historically, palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions were developed in this order.

The most challenging step in carbon–fluorine bond formation via a cross-coupling approach is reductive elimination11, the step in the catalytic cycle in which both carbon and fluorine, initially bound to the metal, expel the catalyst and form a new C–F bond. For reductive elimination of two ligands to occur, there must be sufficient orbital overlap between both metal–ligand σ bonds12. In general, because metal–fluorine bonds are significantly polarized towards fluorine due to fluorine’s high electronegativity and small size, electron density is lacking in the region where it is required for carbon–fluorine bond formation. The high polarization of the metal–fluorine bond results in a significant ionic contribution to the bond, which strengthens the bond and increases the energy barrier to C–F reductive elimination. Furthermore, C–F reductive elimination must be faster than competing non-productive side reactions like hydrolysis of the metal–fluorine bond. Moreover, C–F reductive elimination is just one step in the catalysis cycle; metal–fluorine bond formation can be challenging, but is also vital to success. Methods to form the metal–fluorine bond include ligand exchange with nucleophilic fluoride and oxidative addition with electrophilic fluorination reagents. Strong, polarized, and hydrolyzable metal–fluorine bonds make C–F bond formation via transition metal catalysis a demanding chemical endeavor.

Metal-catalyzed Ar–F bond formation

Conceptually, two fundamentally different classes of fluorination can be distinguished: nucleophilic and electrophilic fluorination. Fluoride anion (F−) or a derivative thereof, such as tetrafluoroborate (BF4−), is the fluorine source in nucleophilic fluorination reactions, and an electrophilic fluorination reagent, such as XeF2, is the source of fluorine in electrophilic fluorination reactions. Transition metals, a priori, are not biased to either nucleophilic or electrophilic fluorination, and the same metal may be successfully employed in both reaction classes. Selection of appropriate transition metals for carbon–fluorine bond formation can be guided by evaluation of metal–fluorine bond strength: Early transition metal fluorides generally have stronger metal–fluorine bonds compared to late transition metals due to π-donation from the fluoride ligand into the empty d orbitals on the metal, and also have more polarized metal–fluorine σ bonds. Consequently, research toward C–F bond-formation catalysis has largely focused on late transition metal complexes.

In 2002, the late transition metal copper, in the form of the electrophilic fluorination reagent CuF2, was used in the oxidation of benzene (C6H6) to fluorobenzene (C6H5F) at 450–550 °C22. The copper reagent can be regenerated after fluorination, and the reaction approach has the potential to lead to a practical copper-catalyzed synthesis of simple fluorinated arenes. Currently, only structurally simple arenes such as fluorobenzene, fluorotoluenes, and difluorobenzenes can be synthesized with the CuF2-mediated process, and the reaction is characterized by low regioselectivity when substituents are present on the arene.

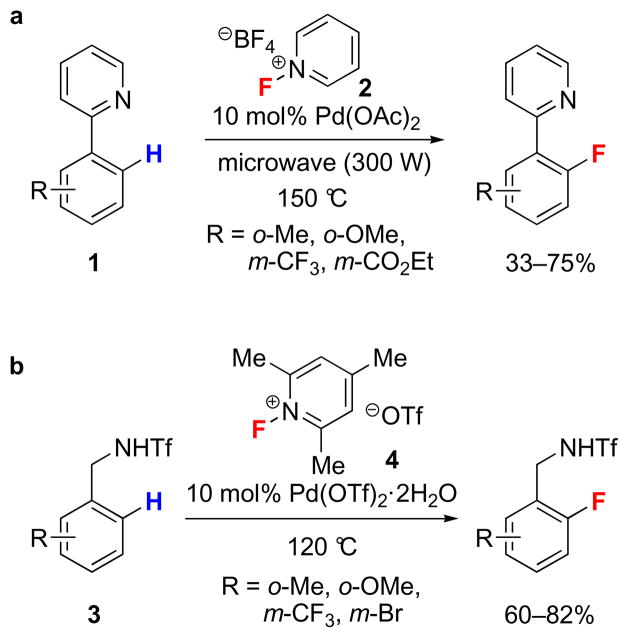

Regioselective functionalization of Caryl–H (Ar–H) bonds by transition metals under less harsh conditions has been achieved through the use of directing groups23. Covalently attached to the aryl ring, directing groups coordinate to a transition metal and lower the activation energy for C–H bond cleavage preferentially, by positioning the transition metal in proximity to specific C–H bonds. The direct transformation of a C–H bond to a C–F bond is an attractive feature of directed electrophilic fluorination in terms of efficiency. Application of the directing group strategy to arene fluorination was first reported in 200624. Phenylpyridine derivatives (1) were fluorinated at the ortho positions in the presence of Pd(OAc)2 and an electrophilic fluorination reagent (Fig. 1a). A similar palladium-catalyzed directed electrophilic fluorination of Ar–H bonds of N-benzyltriflamide derivatives (3) was reported in 2009 (Fig. 1b)25. The triflamide directing group can be easily converted into a variety of other functional groups. Current limitations of the directing group approach include the restriction that fluorine can only be incorporated at the position ortho to the directing group, the requirement for blocking groups to prevent ortho, ortho′-difluorination, and the need for a directing group itself. If the directing group is part of the desired molecule, the approach is efficient, but directing groups and functional groups that are derived from directing groups are often not desired in the final molecule, and easily removable directing groups are rare.

Figure 1. Directed electrophilic palladium-catalyzed Ar–F bond-forming reactions.

a, The first palladium-catalyzed fluorination of organic molecules. Phenylpyridine derivatives (1) were fluorinated in the presence of 10 mol% of Pd(OAc)2 and the electrophilic fluorination reagent N-fluoropyridinium tetrafluoroborate (2) under microwave irradiation. b, A palladium-catalyzed directed electrophilic fluorination of C–H bonds of N-benzyltriflamide derivatives (3) with the catalyst Pd(OTf)2·2H2O and the electrophilic fluorination reagent N-fluoro-2,4,6-trimethylpyridinium triflate (4). (Ac: acetyl, Me: methyl, Et: ethyl, Tf: trifluoromethanesulfonyl).

The mechanisms of the directed electrophilic fluorination reactions shown in Figure 1 are still unknown. After cyclopalladation, the key C–F bond-forming event could occur either from a Pd(II) center without change in the oxidation state of the metal, like in the electrophilic fluorination of an aryl Grignard reagent26,27, or from a higher oxidation state palladium complex, such as a dinuclear Pd(III)28 or a Pd(IV)29,30 complex, via C–F reductive elimination. Reductive elimination from transition metal complexes to form C–F bonds was long unknown. Only in 2008 was an isolated aryltransition metal fluoride complex reported to undergo C–F reductive elimination31,32.

Transition-metal-catalyzed cross coupling between an electrophile and a nucleophile is currently a more general approach for C–F bond formation because it does not rely on directing groups. Studies to use palladium-, rhodium-, and copper-based cross-coupling reactions for C–F bond formation have been documented since the late 1990’s33–35, but only recently has successful fluorination by catalysis been achieved, in large part due to the development of metal complexes that can undergo C–F reductive elimination.

Theoretical studies on the fundamental difficulties associated with C–F reductive elimination from arylpalladium(II) fluoride complexes were reported in 200736. Reductive elimination should occur most readily from a mononuclear three-coordinate, T-shaped palladium complex, with the aryl ligand and the fluoride ligand oriented cis to each other. However, T-shaped arylpalladium(II) fluoride complexes are often less stable than their corresponding dimeric form, in which two T-shaped palladium complexes come together, with both fluorine ligands bound to both palladium atoms. Reductive elimination from such a bis-μ-fluoride dimer is significantly more difficult than from the T-shaped monomer; in fact, to date, it has never been observed. Large ligands on palladium destabilize the dimer relative to the monomer and therefore increase the concentration of the mononuclear three-coordinate arylpalladium(II) fluoride complex for subsequent C–F reductive elimination. In line with this reasoning, the use of the bulky monodentate phosphine ligand t-Bu-XPhos resulted in C–F bond formation from an arylpalladium(II) fluoride complex, albeit in only 10% yield36. The first observation of Ar–F bond formation from an arylpalladium(II) fluoride complex was a significant and promising result, but conclusive evidence for concerted C–F reductive elimination was not obtained and other mechanisms of C–F bond formation are possible37.

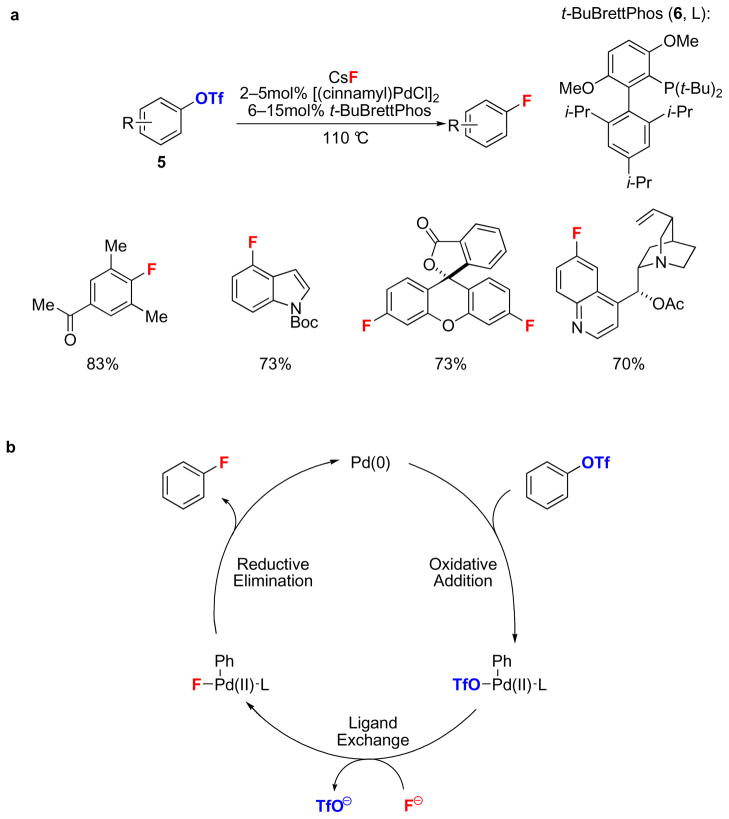

The first palladium(0)-catalyzed Ar–F bond-forming cross-coupling reaction was reported in 2009 using aryl triflates (5) and CsF as a nucleophilic fluorine source (Fig. 2a)38. As predicted by theory, the use of a bulky monodentate phosphine ligand, t-BuBrettPhos (6)39, to access three-coordinate arylpalladium(II) fluoride complexes was key to success (Fig. 2b). An arylpalladium(II) fluoride complex supported by 6 was shown to be effective for C–F reductive elimination38. Arenes with a wide range of electronic properties and a variety of heterocycles could be fluorinated with this method. Sterically congested arenes and arenes bearing electrophilic and nucleophilic function groups could be fluorinated as well. For a few substrates, undesired constitutional isomers were formed as byproducts when para-electron-donating or meta-electron-withdrawing groups were present. While the mechanism for the formation of the constitutional isomers has not yet been elucidated, the isomers could arise from a competing benzyne pathway, due to high reaction temperatures and dried, basic fluoride. The reaction must be performed under anhydrous conditions, and substrates with protic functional groups were not demonstrated to undergo fluorination, possibly due to the tendency of fluoride to form strong hydrogen bonds. Hydrogen bond formation between protic functional groups or water with arylpalladium(II) fluorides could stabilize the ground state of the arylpalladium(II) fluoride complex, which increases the activation barrier to C–F reductive elimination36. Water could also result in hydrolysis of the Pd–F bond at a rate faster than the rate of C–F reductive elimination. In nucleophilic fluorination, as shown in Figure 2, fluoride serves as the nucleophile and the aryl reaction component, for example an aryl triflate or an aryl bromide, serves as the electrophile. In 2008, C–F bond formation by a complementary approach between a nucleophilic aryl group and an electrophilic fluorination reagent was reported40. A variety of functionalized arylboronic acids are suitable substrates for transmetallation onto a palladium(II) complex; subsequent treatment with the electrophilic fluorination reagent F-TEDA-BF4 (Selectfluor®) afforded the corresponding fluoroarenes. C–F bond formation occurred via fluorination of the transition metal, followed by C–F reductive elimination, which established the viability of Ar–F reductive elimination from a transition metal complex31,32.

Figure 2. Nucleophilic palladium-catalyzed Ar–F bond-forming reaction.

a, The first nucleophilic palladium-catalyzed Ar–F bond-forming reaction of aryl triflates (5) with CsF as the fluorine source, the palladium(0) catalyst precursor [(cinnamyl)PdCl]2, and the sterically demanding ligand t-BuBrettPhos (6). b, The proposed mechanism for the Pd-catalyzed nucleophilic Ar–F bond-forming reaction is comprised of three elementary steps: oxidative addition, ligand exchange, and C–F reductive elimination. (L: ligand, t-Bu: tert-butyl, i-Pr: iso-propyl, Boc: tert-butoxylcarbonyl, Ph: phenyl).

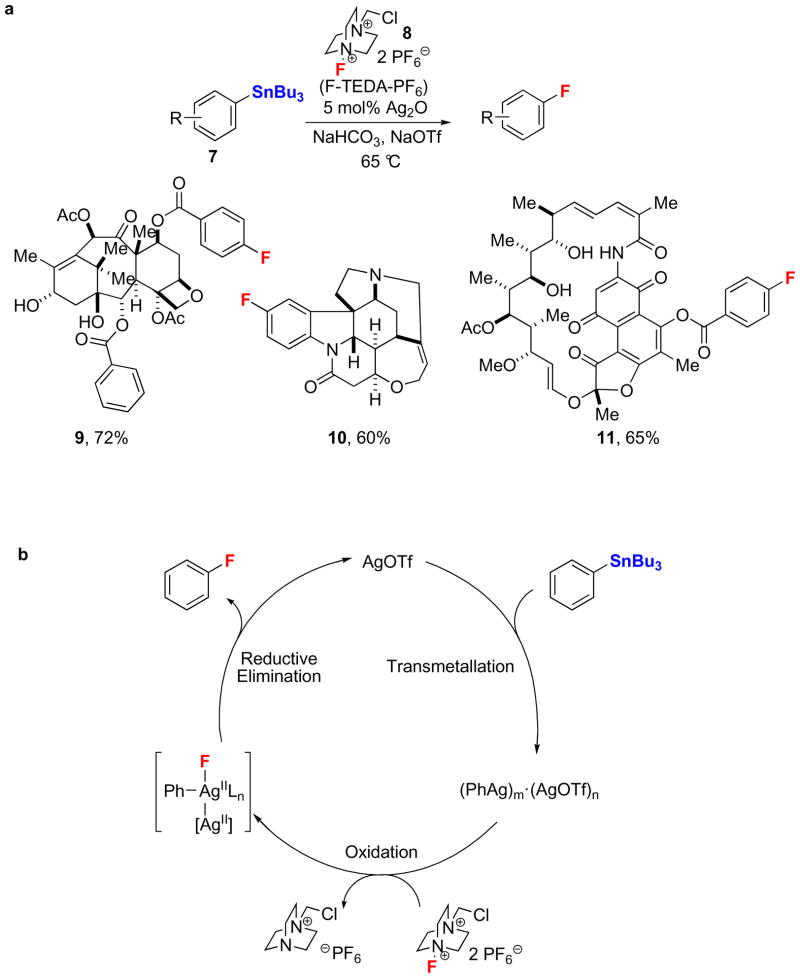

Reductive elimination of C–F bonds from transition metal fluorides need not be limited to palladium. The late transition metal silver has been shown to mediate the electrophilic fluorination of arylboronic acids41 and aryl stannanes42. Following the initial discovery of general silver-mediated fluorination or arenes, a silver-catalyzed electrophilic Ar–F bond-forming reaction for aryl stannanes (7) using Ag2O and the electrophilic fluorination reagent F-TEDA-PF6 (8) was developed (Fig. 3a)43. Several functional groups are tolerated under the reaction conditions. The reaction is applicable to late-stage fluorination of complex small molecules including taxol (9), strychnine (10), and rifamycin (11) derivatives. Few nucleophilic functional groups, including certain amines and sulfides that are generally compatible with nucleophilic fluorination reactions, are incompatible with the electrophilic fluorination reaction. Current challenges associated with the silver-catalyzed electrophilic fluorination include the use of toxic aryl stannane starting materials and the additional synthetic steps required for their preparation from Ar–OH or Ar–H bonds, typically via aryl triflates or aryl halides44.

Figure 3. Electrophilic silver-catalyzed Ar–F bond-forming reaction.

a, The first silver-catalyzed Ar–F bond-forming reaction. Aryl stannane derivatives (7) were fluorinated using 5 mol% of Ag2O as catalyst and the electrophilic fluorination reagent F-TEDA-PF6 (8). The reaction was applied to late-stage fluorination of complex small molecules, including taxol (9), strychnine (10), and rifamycin (11) derivatives. b, The proposed mechanism of the silver-catalyzed electrophilic fluorination includes three elementary steps: transmetallation, oxidation by an electrophilic fluorination reagent, and C–F reductive elimination. (Bu: butyl).

The proposed mechanism of the silver-catalyzed electrophilic Ar–F bond-forming reaction consists of three elementary steps: transmetallation, silver-based oxidation by an electrophilic fluorination reagent, and C–F reductive elimination (Fig. 3b). Aryl transmetallation from tin to silver(I) affords arylsilver(I) species, which are possibly aggregated with additional silver(I) under conditions of catalysis. It was suggested that subsequent silver-based fluorination affords a multinuclear high-valent arylsilver fluoride complex, such as the dinuclear AgII–AgII complex depicted in Figure 3b. The proposed mechanism for the silver-catalyzed fluorination reaction is distinct from most conventional cross-coupling reactions due to the redox participation of multiple metal centers. The facile C–F bond formation from silver, which enabled fluorination of complex molecules, may be due to metal-metal redox interactions that lower the barrier to C–F reductive elimination compared to mononuclear complexes45. Silver-catalyzed carbon–heteroatom cross-coupling reactions had not been reported previously.

Metal-catalyzed Ar–CF3 bond formation

Similar to incorporation of fluorine, the introduction of trifluoromethyl (CF3) groups into organic molecules can substantially alter their properties, such as metabolic stability, lipophilicity, and ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier1–4,46,47. Trifluoromethyl groups are distinct from other alkyl groups such as the methyl (CH3) group, both in terms of electronic structure and reactivity; the CF3 group has the same electronegativity as chlorine (electronegativities: Cl, CF3 = 3.2), and is similar in size to an isopropyl (i-Pr) group (van der Waals radii: i-Pr, CF3 = 2.2 Å)48. Trifluoromethyl groups, when bound to transition metals, can undergo side reactions, such as fluoride elimination49,50, that other alkyl groups cannot. Therefore, the trifluoromethyl group should be considered more appropriately as its own functional group rather than as a substituted methyl group. A conventional synthesis of benzotrifluorides, arenes with a CF3 group, involves radical chlorination of toluene derivatives followed by chlorine–fluorine51. Only structurally simple benzotrifluorides that can tolerate such harsh reaction conditions can be accessed in this manner. Like C–F bond formation, C–CF3 bond formation has its own challenges: the high group electronegativity of 3.2 of a trifluoromethyl group increases the activation barrier of C–CF3 reductive elimination; only few nucleophilic and electrophilic trifluoromethylating reagents are commercially available; and the strong metal–CF3 bonding, in part due to bonding interactions between metal-d orbitals and the σ*C–F orbitals, make transition-metal-catalyzed C–CF3 bond formation difficult52.

Ar–CF3 reductive elimination from the palladium(II) complex [XantphosPd(Ph)CF3] upon heating to 80 °C for 3 hours was reported in 200653. While Ar–CF3 reductive elimination is challenging54–57, this result suggested that C–CF3 bond formation by transition metal catalysis should be more straightforward than C–F bond formation, because Ar–F reductive elimination from the corresponding fluoride complex has not been observed. In fact, all elementary steps required for a catalysis cycle for C–CF3 bond formation have been shown to work independently on isolated complexes53. The challenge for developing a palladium-catalyzed aryl trifluoromethylation reaction was to develop reaction conditions that allowed all elementary steps, oxidative addition, transmetallation to make a Pd–CF3 bond, and Ar–CF3 reductive elimination, to proceed in the same reaction vessel, as required for catalysis.

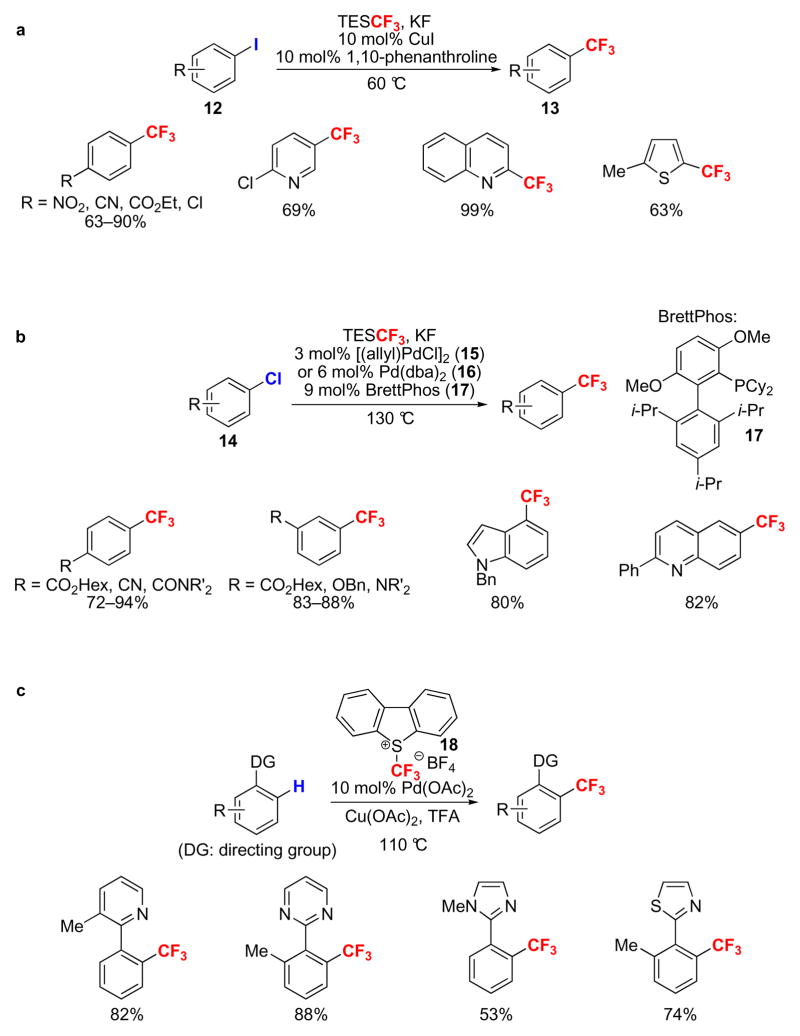

The first Ar–CF3 bond-forming cross-coupling reaction was reported in 196958. Benzotrifluoride was obtained in 45% yield by heating iodobenzene and trifluoroiodomethane in DMF with activated copper bronze at 150 °C. Since the initial report on Ar–CF3 cross coupling, several modifications to the reaction conditions and reagents have been reported59,60. However, only in 2009, was a copper-catalyzed Ar–CF3 bond-forming reaction achieved61. Electron-poor aryl iodides (12) were converted to benzotrifluorides (13) with catalytic CuI and 1,10-phenanthroline (Fig. 4a). The reaction may proceed through generation of a copper-trifluoromethyl complex62–64 followed by oxidative addition to form an arylcopper(III) intermediate65–68, but details of the reaction mechanism remain unclear. More recently, several copper-mediated trifluoromethylation reactions have been reported69–73.

Figure 4. Transition-metal-catalyzed Ar–CF3 bond-forming reactions.

a, The first copper-catalyzed Ar–CF3 bond-forming reaction of aryl iodides (12) with 10 mol% of CuI and 1,10-phenanthroline. b, The first palladium-catalyzed nucleophilic Ar–CF3 bond-forming reaction of aryl chlorides (14) with TESCF3 as the CF3 source, 6 mol% of a palladium(0) precursor complex (15 or 16), 9 mol% of the sterically demanding ligand BrettPhos (17), and KF. c, The first palladium-catalyzed directed electrophilic Ar–CF3 bond-forming reaction with 10 mol% of Pd(OAc)2 and the electrophilic trifluoromethylation reagent S-(trifluoromethyl)dibenzothiophenium tetrafluoroborate (18). (TES: triethylsilyl, dba:dibenzylideneacetone, Hex: hexyl, Bn, benzyl, TFA: trifluoroacetic acid).

The first palladium-catalyzed Ar–CF3 bond-forming reaction was reported in 2010 (Fig. 4b)74. The reaction employs aryl chlorides and (trifluoromethyl)triethylsilane (TESCF3) as the CF3 source. A large substrate scope was shown, but substrates with protic functional groups were not demonstrated to undergo trifluoromethylation, possibly because protic functional groups accelerate decomposition of TESCF3 or aryl(trifluoromethyl)palladium(II) and arylpalladium(II) fluoride complexes. In both the copper- and palladium-catalyzed trifluoromethylation reaction, a nucleophilic trifluoromethyl unit is slowly generated in situ from TESCF3 and KF, thus reducing the potential for side reactions to occur; the use of reagents that would generate the trifluoromethyl anion equivalent more quickly, such as (trifluoromethyl)trimethylsilane (TMSCF3), result in lower trifluoromethylation yields.

Using a directing group strategy, Ar–CF3 bond formation directly from C–H bonds can be performed with Pd(OAc)2 and an electrophilic trifluoromethylation reagent (Fig. 4c)75. Heterocycles including pyridine, pyrimidine, imidazole, and thiazole can be used as directing groups. Limitations of the reaction include the need for a directing group and the current functional group tolerance; only methoxy, chloro, and methyl groups were shown to be compatible with the reaction conditions.

Catalyzed Csp3–F and Csp3–CF3 bond formation

Organic molecules with fluorine atoms or trifluoromethyl groups bonded to sp3-hybridized carbon (Csp3) atoms are present in pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, dyes, and materials1–4,76–78. Reactions utilizing fluoride as a nucleophile for aliphatic fluorination have been known for more than 100 years79 and racemic syntheses of α-fluoro or α-trifluoromethyl carbonyl compounds have been known shortly after the development of electrophilic fluorination and trifluoromethylation reagents, respectively10,80. Yet, until recently enantioselective construction of Csp3–F and Csp3–CF3 bonds mainly relied on substitution reactions at existing stereogenic centers with fluoride as a nucleophile or enantioselective addition reactions of trifluoromethyl anion equivalents to carbonyl groups76,78 or imines81. In contrast to aromatic fluorination, most of the recent advances for aliphatic fluorination did not require the development of new reactivity, but rather the development of enantioselective reactions, which employed established reactivity76–78. Like aromatic fluorination, aliphatic fluorination benefited from developments in catalysis when compared to conventional fluorination reactions.

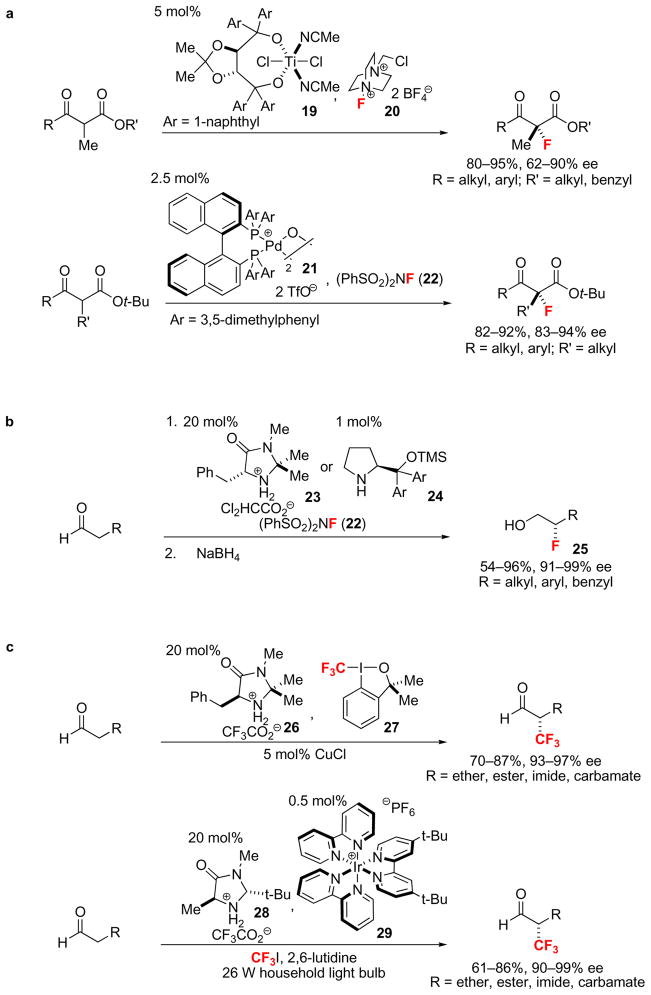

The electrophilic fluorination of metal enolates is a well-known process10, but discrimination of the two enantiotopic faces of the electron-rich π-system for reaction with the electrophilic fluorinating reagent has only been achieved recently. In 2000, a titanium complex (19) was demonstrated to control facial selectivity in the reaction of branched α-ketoesters with Selectfluor® (20) (Fig. 5a, top)82. This method was the first example of enantioselective metal-catalyzed Csp3–F bond formation. Two years later, an improved catalysis system was reported using a palladium catalyst (21) (Fig. 5a, bottom)83. Following these two successful examples, fluorination of the α-position of carbonyls using organometallic complexes has been investigated intensively, leading to the development of α-fluorination of malonates, α-carbamoyl esters, α-ketophosphates, and α-cyanophosphates76,77.

Figure 5. Catalytic enantioselective Csp3–F and Csp3–CF3 bond-forming reactions.

a, Metal-catalyzed enantioselective Csp3–F bond-forming reactions. Branched β-ketoesters were fluorinated using 5 mol% of a Ti-TADDOL catalyst (19) and Selectfluor® (20) or 2.5 mol% of μ-hydroxo-palladium-BINAP complex (21) and N-fluorobenzenesulfonimide (22). b, Examples of organocatalytic enantioselective Csp3–F bond-forming reactions. Amino acid-derived organocatalysts (23 and 24) and N-fluorobenzenesulfonimide (22) were utilized to fluorinate α-unbranched aldehydes. Due to the potentially facile racemization of α-fluoroaldehydes, the corresponding fluorohydrins (25) were isolated after reduction with NaBH4 in 54–96% yield and 91–99% ee. c, Enantioselective Csp3–CF3 bond-forming reactions. The mechanism of the two presented reactions differ conceptually, but both afford α-trifluoromethylated aldehydes in good yield and high enantioselectivity either using hypervalent iodine 27 as the CF3 source and amine catalyst 26 or using trifluoroiodomethane as the CF3 source, 20 mol% amine catalyst 28, 0.5 mol% Ir catalyst 29 and light. (TMS: trimethylsilyl).

Similar to the electron-rich π-systems of metal enolates, enamines can undergo electrophilic fluorination. Starting in 2005, advances in the field of organocatalytic enantioselective fluorination were reported. Fluorination reactions of cyclohexanone with Selectfluor® (20) and proline derivatives as catalysts were investigated84. Immediately thereafter, three other research reports85–87 independently disclosed enantioselective α-fluorination of aldehydes using electrophilic fluorination reagents and chiral secondary amine catalysts derived from amino acids such as 23 and 24 (Fig 5b). The organocatalyst forms transient chiral, nucleophilic enamine intermediates, which in turn react with the electrophilic fluorinating reagent diastereoselectively. Subsequent hydrolysis of the iminium intermediate forms the chiral fluoroaldehyde and regenerates the organocatalyst. More recently, electrophilic, enantioselective fluorination of enol ethers, allyl silanes, oxindoles, and cyclic ketones were reported using cinchona alkaloids as a catalysts88,89. Nucleophilic, aliphatic fluorination by chiral organocatalysis has not yet been established, but transition-metal catalysis based on chiral palladium allyl complexes can be used to make allyl fluorides90 enantioselectively91.

Enantioselective α-trifluoromethylation of carbonyls can proceed analogously to organocatalyzed fluorination, with appropriate electrophilic trifluoromethylation reagents. Two enantioselective α-trifluoromethylation reactions of aldehydes have been reported. Aldehydes were trifluoromethylated enantioselectively with the hypervalent iodine reagent 2792 as the electrophilic reagent, and the chiral imidazolidinone catalyst 26 (Fig. 5c, top)93.

In contrast to the other organocatalyzed reactions discussed here, organocatalyzed trifluoromethylation of aldehydes via photoredox catalysis proceeds by a mechanism distinct from conventional fluorination and trifluoromethylation reactivity. Photoredox catalysis operates via one-electron pathways94 while the other presented organocatalyzed reaction likely proceeds via two-electron pathways. Using the trifluoromethylation reagent iodotrifluoromethane, the chiral organocatalyst 28, the iridium catalyst 29, and light from a fluorescent light bulb, aldehydes were transformed into the corresponding α-trifluoromethyl aldehydes with high enantioselectivity (Fig. 5c, bottom)95. Under the reaction conditions, trifluoromethyl radicals are generated by single electron transfer from the photolytically activated Ir catalyst, which in turn oxidize in situ generated enamines to form C–CF3 bonds.

Conclusions

Fluorinated organic molecules are often valuable but generally challenging to synthesize efficiently. Fluorination reactions developed in the past five years now give access to complex fluorinated molecules that were not readily available before. The recent success in fluorine incorporation can be attributed to the design of previously unavailable transition metal complexes, and the merger of modern synthesis techniques such as organocatalysis with fluorination chemistry. Catalysis has played a major role in the recent development of organofluorine chemistry. For example, new catalysts can selectively lower the activation barrier of C–F and C–CF3 bond formation in aromatic fluorination and trifluoromethylation, respectively, and new chiral catalysts can distinguish between the enantiotopic faces of nucleophiles for aliphatic C–F and C–CF3 bond formation.

Better prediction of the reactivity of well-defined transition metal complexes has supported the advances in nucleophilic aromatic fluorination. For example, rational ligand development was crucial for the palladium-catalyzed C–F cross-coupling reaction described in Figure 2. Readily available starting materials such as aryl triflates and fluoride, arguably the simplest and most desirable source of fluorine, can be employed in this reaction. Yet, whenever fluoride is used, its basicity and the basicity of the transition metal complexes derived from it are often problematic because water and protic functional groups lower the desired reactivity. Future nucleophilic fluorination reactions will benefit from the availability of transition metal complexes of lower basicity, which, most likely, will be achieved through further transition metal complex and ligand design. Moreover, reaction methods based on other transition metals may be suitable for more widely applicable nucleophilic fluorination. In particular, the coinage metals copper, silver, and gold have shown intriguing reactivity and merit further study.

Current electrophilic fluorination reactions have different challenges. Silver-catalyzed electrophilic fluorination of aryl stannanes has the largest demonstrated substrate scope and is amenable to the fluorination of complex molecules. However, aryl stannanes are toxic and more difficult to synthesize than aryl triflates or halides, which reduces the method’s practicality. Practical cross-coupling reactions should employ readily accessible starting materials like aryl chlorides and phenols. Ideally, regioselective electrophilic fluorination reactions would transform C–H bonds into C–F bonds directly. C–H bond functionalization reactions would be the most efficient means of incorporating fluorine into complex molecules, but are currently limited to very simple arenes like benzene and arenes with directing groups. Future advances in the field of selective C–H functionalization combined with modern fluorination chemistry will likely result in practical fluorination reactions. For example, a general, regioselective fluorination of C–H bonds using fluoride and an economically viable oxidant would significantly advance the field.

The reactions presented in this Review have begun to address some of the unmet needs in organofluorine chemistry. In medicinal chemistry, milligram to gram quantities of functionalized fluorinated molecules are more readily accessible now than before. On the other hand, current methods still lack practicality and cost efficiency for general use in large-scale manufacturing. And while fluorination to prepare tracer molecules for positron emission tomography (PET) with the isotope fluorine-18 (18F) only requires small amounts of material, the recent advances in fluorination technology have not given access to general 18F-tracer synthesis, because the stringent reaction requirements for practical and general 18F-fluorination are not met. Future research in fluorination chemistry will need to focus on the development of more general and practical fluorination reactions.

References

- 1.Müller K, Faeh C, Diederich F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: Looking beyond intuition. Science. 2007;317:1881–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Purser S, Moore PR, Swallow S, Gouverneur V. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:320–330. doi: 10.1039/b610213c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeschke P. The unique role of fluorine in the design of active ingredients for modern crop production. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:570–589. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hung MH, Farnham WB, Feiring AE, Rozen S. Functional Fluoromonomers and Fluoropolymers. In: Hougham G, Cassidy PE, Johns K, Davidson T, editors. Fluoropolymers: Synthesis. Vol. 1. Plenum Publishing Co; 1999. pp. 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ametamey SM, Honer M, Schubiger PA. Molecular imaging with PET. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1501–1516. doi: 10.1021/cr0782426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Hagan D. Understanding organofluorine chemistry. An introduction to the C–F bond. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:308–319. doi: 10.1039/b711844a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curran DP. Strategy-level separations in organic synthesis: From planning to practice. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:1174–1196. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980518)37:9<1174::AID-ANIE1174>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patterson JC, II, Mosley ML. How available is positron emission tomography in the United States? Mol Imaging Biol. 2005;7:197–200. doi: 10.1007/s11307-005-4116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirk KL. Fluorination in medicinal chemistry: Methods, strategies, and recent developments. Org Process Res Dev. 2008;12:305–321. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furuya T, Kuttruff CA, Ritter T. Carbon–fluorine bond formation. Curr Opin Drug Disc Dev. 2008;11:803–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grushin VV. The organometallic fluorine chemistry of palladium and rhodium: Studies toward aromatic fluorination. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:160–171. doi: 10.1021/ar9001763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furuya T, Klein JEMN, Ritter T. C–F bond formation for the synthesis of aryl fluorides. Synthesis. 2010:1804–1821. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1218742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirsch P. Modern Fluoroorganic Chemistry: Synthesis, Reactivity, Applications. Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gribble GW. In: Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products. Herz W, Kirby GW, Moore RE, Steglich W, Tamm C, editors. Vol. 68. Springer-Verlag/Wien; 1996. pp. 1–498. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gribble GW. In: Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products. Kinghord AD, Falk H, Kobayashi J, editors. Vol. 91. Springer-Verlag/Wien; 2009. pp. 1–613. [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Hagan D, Schaffrath C, Cobb SL, Hamilton JTG, Murphy CD. Enzyme catalysed organofluorine synthesis. Nature. 2002;416:279. doi: 10.1038/416279a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong C, et al. Crystal structure and mechanism of a bacterial fluorinating enzyme. Nature. 2004;427:561–565. doi: 10.1038/nature02280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shannon RD. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Cryst. 1976;A32:751–767. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emsley J. Very strong hydrogen bonds. Chem Soc Rev. 1980;9:91–124. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams DJ, Clark JH. Nucleophilic routes to selectively fluorinated aromatics. Chem Soc Rev. 1999;28:225–231. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo Y-R. Handbook of Bond Dissociation Energies in Organic Compounds. CRC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subramanian MA, Manzer LE. A “greener” synthetic route for fluoroaromatics via copper(II) fluoride. Science. 2002;297:1665. doi: 10.1126/science.1076397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cope AC, Siekman RW. Formation of covalent bonds from platinum or palladium to carbon by direct substitution. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:3272–3273. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hull KL, Anani WQ, Sanford MS. Palladium-catalyzed fluorination of carbon–hydrogen bonds. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7134–7135. doi: 10.1021/ja061943k. This paper describes the first Pd-catalyzed C–F bond formation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Mei TS, Yu JQ. Versatile Pd(OTf)2·2H2O-catalyzed ortho-fluorination using NMP as a promoter. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7520–7251. doi: 10.1021/ja901352k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada S, Gavryushin A, Knochel P. Convenient electrophilic fluorination of functionalized aryl and heteroaryl magnesium reagents. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:2215–2218. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anbarasan P, Neumann H, Beller M. Efficient synthesis of aryl fluorides. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:2219–2222. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powers DC, Ritter T. Bimetallic Pd(III) complexes in palladium-catalysed carbon–heteroatom bond formation. Nat Chem. 2009;1:302–309. doi: 10.1038/nchem.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaspi AW, Yahav-Levi A, Goldberg I, Vigalok A. Xenon difluoride induced aryl iodide reductive elimination: A simple access to difluoropalladium(II) complexes. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:5–7. doi: 10.1021/ic701722f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ball ND, Sanford MS. Synthesis and reactivity of a mono-s-aryl palladium(IV) fluoride complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3796–3797. doi: 10.1021/ja8054595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furuya T, Ritter T. Carbon–fluorine reductive elimination from a high-valent palladium fluoride. J Am ChemSoc. 2008;130:10060–10061. doi: 10.1021/ja803187x. This paper describes the first confirmed Ar–F reductive elimination from a transition metal complex. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furuya T, et al. Mechanism of C–F reductive elimination from palladium(IV) fluorides. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3793–3807. doi: 10.1021/ja909371t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fraser SL, Antipin Yu M, Khroustalyov VN, Grushin VV. Molecular fluoro palladium complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:4769–4770. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pilon MC, Grushin VV. Synthesis and characterization of organopalladium complexes containing a fluoro ligand. Organometallics. 1998;17:1774–1781. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grushin VV. Palladium fluoride complexes: One more step toward metal-mediated C–F bond formation. Chem —Eur J. 2002;8:1006–1014. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020301)8:5<1006::aid-chem1006>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yandulov DV, Tran NT. Aryl–fluoride reductive elimination from Pd(II): Feasibility assessment from theory and experiment. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1342–1358. doi: 10.1021/ja066930l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grushin VV, Marshall WJ. Ar–F Reductive elimination from palladium(II) revisited. Organometallics. 2007;26:4997–5002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watson DA, et al. Formation of ArF from LPdAr(F): Catalytic conversion of aryl triflates to aryl fluorides. Science. 2009;325:1661–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.1178239. This paper reports the first functional-group-tolerant Pd-catalyzed Ar–F bond formation using aryl triflates and fluoride. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fors BP, Watson DA, Biscoe MR, Buchwald SL. A Highly active catalyst for Pd-catalyzed amination reactions: Cross-coupling reactions using aryl mesylates and the highly selective monoarylation of primary amines using aryl chlorides. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13552–13554. doi: 10.1021/ja8055358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furuya T, Kaiser HM, Ritter T. Palladium-mediated fluorination of arylboronic acids. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:5993–5996. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furuya T, Ritter T. Fluorination of boronic acids mediated by silver(I) triflate. Org Lett. 2009;11:2860–2863. doi: 10.1021/ol901113t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furuya T, Strom AE, Ritter T. Silver-mediated fluorination of functionalized aryl stannanes. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1662–1663. doi: 10.1021/ja8086664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang P, Furuya T, Ritter T. Silver-catalyzed late-stage fluorination. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12150–12154. doi: 10.1021/ja105834t. This paper reports the first functional-group-tolerant Ag-catalyzed Ar–F bond formation using aryl stannanes and an electrophilic fluorinating reagent. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Azizian H, Eaborn C, Pidcock A. Synthesis of organotrialkylstannanes. The reaction between organic halides and hexaalkyldistannanes in the presence of palladium complexes. J Organomet Chem. 1981;215:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Powers DC, Benitez D, Tkatchouk E, Goddard WA, III, Ritter T. Bimetallic reductive elimination from dinuclear Pd(III) complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14092–14103. doi: 10.1021/ja1036644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma JA, Cahard D. Strategies for nucleophilic, electrophilic, and radical trifluoromethylations. J Fluorine Chem. 2007;128:975–996. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shimizu M, Hiyama T. Modern synthetic methods for fluorine-substituted target molecules. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:214–231. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bott G, Field LD, Sternhell S. Steric effects. A study of a rationally designed system. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:5618–5626. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jenson MB, et al. Reactivity and structure of CF3I on Ru(001) J Phys Chem. 1995;99:8736–8744. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Z-M, Zhou X-L, Kiss J, White JM. Interaction of CF3I with. Surf Sci. 1993;286(Pt 111):233–245. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yagupolskii LM. Houben-Weyl: Methods of Organic Chemistry. E10a. Thieme; Stuttgart: 2000. Organo-Fluorine Compounds; pp. 509–534. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark HC, Tsai JH. Bonding in fluorinated organometallic compounds. J Organomet Chem. 1967;7:515–517. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grushin VV, Marshall WJ. Facile Ar–CF3 bond formation at Pd. Strikingly different outcomes of reductive elimination from [(Ph3P)2Pd(CF3)Ph] and [(Xantphos)Pd(CF3)Ph] J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12644–12645. doi: 10.1021/ja064935c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Culkin DA, Hartwig JF. Carbon–carbon bond-forming reductive elimination from arylpalladium complexes containing functionalized alkyl groups. Influence of ligand steric and electronic properties on structure, stability, and reactivity. Organometallics. 2004;23:3398–3416. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grushin VV, Marshall WJ. Unexpected H2O-induced Ar–X activation with trifluoromethylpalladium(II) aryls. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4632–4641. doi: 10.1021/ja0602389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ball ND, Kampf JW, Sanford MS. Aryl–CF3 bond-forming reductive elimination from palladium(IV) J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2878–2879. doi: 10.1021/ja100955x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ye Y, Ball ND, Kampf JW, Sanford MS. Oxidation of a cyclometalated Pd(II) dimer with “CF3+”: Formation and reactivity of a catalytically competent monomeric Pd(IV) aquo complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14682–14687. doi: 10.1021/ja107780w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mcloughlin VCR, Thrower J. A route to fluoroalkyl-substituted aromatic compounds involving fluoroalkylcopper intermediates. Tetrahedron. 1969;25:5921–5940. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kobayashi Y, Kumadaki I. Trifluoromethylation of aromatic compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969;10:4095–4096. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carr GE, Chambers RD, Holmes TF, Parker DG. Sodium perfluoroalkane carboxylates as sources of perfluoroalkyl groups. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1988;1:921–926. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oishi M, Kondo H, Amii H. Aromatic trifluoromethylation catalytic in copper. Chem Commun. 2009:1909–1911. doi: 10.1039/b823249k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wiemers DA, Burton DJ. Pregeneration, spectroscopic detection, and chemical reactivity of (trifluoromethyl)copper, an elusive and complex species. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:832–834. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dubinina GG, Furutachi H, Vicic DA. Active trifluoromethylating agents from well-defined copper(I)-CF3 complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8600–8601. doi: 10.1021/ja802946s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dubinina GG, Ogikubo J, Vicic DA. Structure of bis(trifluoromethyl)cuprate and its role in trifluoromethylation reactions. Organometallics. 2008;27:6233–6235. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Monnier F, Taillefer M. Catalytic C–C, C–N, and C–O Ullmann-type coupling reactions. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:6954–6971. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Altman RA, Hyde AM, Huang X, Buchwald SL. Orthogonal Pd- and Cu-based catalyst systems for C- and N-arylation of oxindoles. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9613–9620. doi: 10.1021/ja803179s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tye JW, Weng Z, Johns AM, Incarvito CD, Hartwig JF. Copper complexes of anionic nitrogen ligands in the amidation and imidation of aryl halides. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9971–9983. doi: 10.1021/ja076668w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huffman LM, Stahl SS. Carbon–nitrogen bond formation involving well-defined aryl–copper(III) complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9196–9197. doi: 10.1021/ja802123p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Knauber T, Arikan F, Röschenthaler GV, Gooβen LJ. Copper-catalyzed trifluoromethylation of aryl iodides with potassium (trifluoromethyl)trimethoxyborate. Chem—Eur J. 2011;17:2689–2697. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chu L, Qing FL. Copper-mediated oxidative trifluoromethylation of boronic acids. Org Lett. 2010;12:5060–5063. doi: 10.1021/ol1023135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang CP, et al. Copper-mediated trifluoromethylation of heteroaromatic compounds by trifluoromethyl sulfonium salts. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:1896–1900. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Senecal TD, Parsons AT, Buchwald SL. Room temperature aryl trifluoromethylation via copper-mediated oxidative cross-coupling. J Org Chem. 2011;76:1174–1176. doi: 10.1021/jo1023377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morimoto H, Tsubogo T, Litvinas ND, Hartwig JF. A broadly applicable copper reagent for trifluoromethylations and perfluoroalkylations of aryl iodides and bromides. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50 doi: 10.1002/anie.201100633. Early View. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cho EJ, et al. The palladium-catalyzed trifluoromethylation of aryl chlorides. Science. 2010;328:1679–1681. doi: 10.1126/science.1190524. This paper describes the first functional-group-tolerant Pd-catalyzed Ar–CF3 bond formation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang X, Truesdale L, Yu JQ. Pd(II)-catalyzed ortho-trifluoromethylation of arenes using TFA as a promoter. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3648–3649. doi: 10.1021/ja909522s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ma J-A, Cahard D. Asymmetric fluorination, trifluoromethylation, and perfluoroalkylation reactions. Chem Rev. 2008;108:PR1–PR43. doi: 10.1021/cr800221v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lectard S, Hamashima Y, Sodeoka M. Recent advances in catalytic enantioselective fluorination reactions. Adv Synth Catal. 2010;352:2708–2732. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shibata N, Mizuta S, Kawai H. Recent advances in enantioselective trifluoromethylation reactions. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2008;19:2633–2644. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Young S. Note on the formation of an alcoholic fluoride. J Chem Soc. 1881;39:489–497. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Umemoto T, Adachi K. New method for trifluoromethylation of enolate anions and applications to regio-, diastereo- and enantioselective trifluoromethylation. J Org Chem. 1994;59:5692–5699. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kawai H, Kusuda A, Nakamura S, Shiro M, Shibata N. Catalytic enantioselective trifluoromethylation of azomethine imines with trimethyl(trifluoromethyl)silane. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:6324–6327. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hintermann L, Togni A. Catalytic enantioselective fluorination of β-ketoesters. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:4359–4362. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001201)39:23<4359::AID-ANIE4359>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hamashima Y, Yagi K, Takano H, Tamás L, Sodeoka M. An efficient enantioselective fluorination of various α-ketoesters catalyzed by chiral palladium complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14530–14531. doi: 10.1021/ja028464f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Enders D, Hüttl MRM. Direct organocatalytic α-fluorination of aldehydes and ketones. Synlett. 2005:991–993. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marigo M, Fielenbach D, Braunton A, Kjærsgaard A, Jørgensen KA. Enantioselective formation of stereogenic carbon–fluorine centers by a simple catalytic method. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:3703–3706. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Steiner DD, Mase N, Barbas CF., III Direct asymmetric α-fluorination of aldehydes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:3706–3710. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beeson TD, MacMillan DWC. Enantioselective organocatalytic α-fluorination of aldehydes. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8826–8828. doi: 10.1021/ja051805f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ishimaru T, et al. Cinchona alkaloid catalyzed enantioselective fluorination of allyl silanes, silyl enol ethers, and oxindoles. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:4157–4161. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kwiatkowski P, Beeson TD, Conrad JC, MacMillan DWC. Enantioselective organocatalytic α-fluorination of cyclic ketones. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1738–1741. doi: 10.1021/ja111163u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hollingworth C, et al. Palladium-catalyzed allylic fluorination. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:2613–2617. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Katcher MH, Doyle AG. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of allylic fluorides. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:17402–17404. doi: 10.1021/ja109120n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Eisenberger P, Gischig S, Togni A. Novel 10-I-3 hypervalent iodine-based compounds for electrophilic trifluoromethylation. Chem—Eur J. 2006;12:2579–2586. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Allen AE, MacMillan DWC. The productive merger of iodonium salts and organocatalysis: A non-photolytic approach to the enantioselective α-trifluoromethylation of aldehydes. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4986–4987. doi: 10.1021/ja100748y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Beeson TD, Mastracchio A, Hong J, Ashton K, MacMillan DWC. Enantioselective organocatalysis using SOMO activation. Science. 2007;316:582–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nagib DA, Scott ME, MacMillan DWC. Enantioselective α-trifluoromethylation of aldehydes via photoredox organocatalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:10875–10875. doi: 10.1021/ja9053338. This paper reports the first example of enantioselective, photoredox/organocatalytic α-trifluoromethylation of aldehydes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wu XF, Anbarasan P, Neumann H, Beller M. From noble metal to Nobel Prize: Palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions as key methods in organic synthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:9047–9050. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.de Meijere A, Diederich F, editors. Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hartwig JF. Carbon–heteroatom bond-forming reductive elimination of amines, ethers, and sulfides. Acc Chem Res. 1998;31:852–860. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hartwig JF. Carbon–heteroatom bond formation catalysed by organometallic complexes. Nature. 2008;455:314–322. doi: 10.1038/nature07369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Muci AR, Buchwald SL. Practical palladium catalysts for C–N and C–O bond formation. In: Miyaura N, editor. Topics in Current Chemistry. Vol. 219. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2001. pp. 131–209. [Google Scholar]