Abstract

Genetic variation in MYH9, encoding non-muscle heavy chain IIA, has been recognized for over a decade as the cause of an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by macrothrombocytopenia, neutrophil inclusions, and glomerular pathology. More recently, genetic variation in the MYH9 region on chromosome 22 has been associated with chronic kidney disease in African-descent individuals. A better understanding of the disease mechanisms responsible for glomerular injury in autosomal dominant MYH9 syndromes will lead to fuller appreciation of the role of this gene in glomerular biology.

In this issue of Kidney International, Sekine and colleagues1 describe the renal manifestations in nine patients with the R702 mutations in MYH9, encoding nonmuscle myosin IIA heavy chain. Describing patients from different families, but with the same mutated amino acid residue (R702C and R702H), this paper provides genotype–phenotype correlations and makes several useful contributions. First, it underscores the rapidity with which chronic kidney disease can progress to end-stage kidney disease in these patients, often in less than 2–3 years. Second, it confirms earlier reports that angiotensin antagonist therapy may reduce proteinuria but does not do so in all patients. Third, it confirms prior observations of glomerular basement membrane (GBM) pathology. Fourth, it demonstrates that the pathologic picture can include segmental glomerulosclerosis, at an early stage of chronic kidney disease, which could indicate primary podocyte injury rather than post-adaptive focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) consequent to a reduced number of functioning nephrons. Fifth, it suggests that MYH9 protein is expressed by podocytes and mesangial cells, as previously reported, and also by tubular cells (including proximal, loop of Henle, and distal tubules) and endothelial cells (interlobular arteries and arterioles and peritubular capillaries).

A set of overlapping syndromes, characterized by macrothrombocytopenia, azurophilic Döhle-like inclusions in neutrophils, sensorineural deafness, cataracts, and glomerular injury, was linked to MYH9 coding region mutations (missense, nonsense, and deletions) in 2000.2,3 The most characteristic finding is the macrothrombocytopenia; some patients have mild to moderate mucocutaneous bleeding diathesis, but others are unaffected. Various names have been used, including giant platelet syndrome (which leads to confusion with other genetic causes of giant platelets, including Bernard–Soulier syndrome), and non-muscle myosin IIA disorders (MYHIIA syndrome) and MYH9 disorders. Recently, MYH9 kidney risk variants have been associated with HIV-associated collapsing glomerulopathy, FSGS, and hypertension-attributed end-stage kidney disease among African-descent populations.4 The term ‘MYH9 disorders’ lumps together the autosomal dominant disorders and the kidney risk variant. Therefore a more distinctive and precise term is preferred for the former category, perhaps autosomal dominant MYH9 (ADM9) spectrum disorders. The ADM9 spectrum comprises at least five syndromes: May–Hegglin anomaly (OMIM 155100), Sebastian syndrome (OMIM 606249), Epstein syndrome (OMIM 153650), Fechtner syndrome (OMIM 153640), and isolated sensorineural deafness (OMIM 603622). Glomerular pathology has been noted in Epstein and Fechtner syndromes, beginning with the original reports describing these syndromes.

Kidney abnormalities, the subject of a recent comprehensive review,5 are seen in about 30%–70% of ADM9 patients. Patients may present with microscopic hematuria, with or without proteinuria. Proteinuria may remain subnephrotic or may become nephrotic. The combination of glomerulopathy, sensorineural deafness, and, in some cases, cataracts may mimic Alport syndrome, but the other features (particularly abnormal platelets and autosomal dominant mode of inheritance) should aid in the clinical distinction.

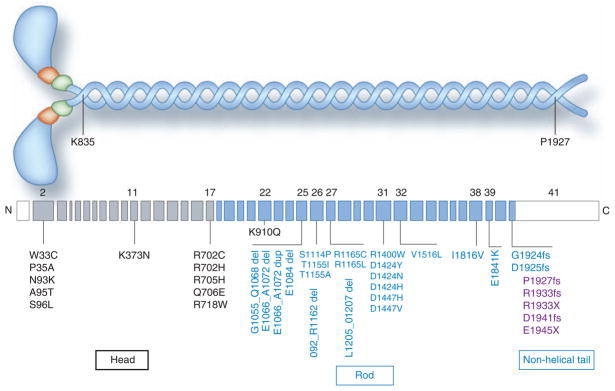

To date, 39 MYH9 mutations, distributed across 12 of the 40 coding exons, have been associated with ADM9 spectrum disorders (Figure 1), tabulated in a comprehensive review.6 These include 26 missense mutations (codon changing), five in-frame deletions, and one duplication. Also, located in the last exon, where a truncated protein is apparently tolerated and therefore is non-lethal, are two nonsense mutations (resulting in a premature stop codon) and five frameshift mutations. Several individuals had multiple mutations, and so the pathogenic mutation is not certain. 6 As shown, 11 mutations occur in the head domain, and the remaining mutations occur in the rod domain of the nonmuscle myosin IIA heavy chain protein. Four residues have been affected by multiple missense mutations: R702, R1165, D1424, and R1933. This observation, together with the frequent occurrence of the same mutation in apparently unrelated families and in individuals with spontaneous mutations, suggests either that there are mutational hot spots, or alternatively that certain residues are particularly important for myosin function and substitutions are not well tolerated. Evidence for or against the latter may come in the near future, when widespread use of whole-genome sequencing makes it possible to study the sequences of all genes, from thousands of individuals (for example, the ongoing 1000 Genomes Project), providing insight into the frequency of rare, phenotypically silent mutations across this and other genes.

Figure 1. Nonmuscle myosin IIA structure and MYH9 exon structure, with autosomal dominant MYH9 mutations.

Above: A schematic of nonmuscle myosin IIA, showing the two heavy chains (encoded by MYH9) in blue (comprising 1960 amino acid residues), the two regulatory light chains in green, and the two essential light chains in orange. The head domain contains the actin-binding domain and the ATPase domain. Transition to the coiled-coil rod domain is shown at amino acid residue K835 (lysine, position 835). Transition to the non-helical extension of the rod domain occurs at P1927 (proline, position 1927). Below: MYH9 exon structure for the most typical mRNA variant, which is 7.5 kb in size and contains 41 exons. The first exon is non-coding (shown in white), and most of the 41st exon is non-coding (shown in white). Exons 2–17 encode the head domain and are shown in gray. Exons 18–41 encode the rod domain, shown in blue. Mutations in the non-helical tail are shown in purple. Shown are 39 MYH9 variants associated with disease. Most are mutations, but not all variants have been proven to cause disease, as some individuals have two variants and the pathogenic roles for both variants have not been established. Data from ref. 6; in that reference the coding exons are numbered from 1 to 40. Abbreviations: del, deletion; dup, duplication; fs, frameshift; X, stop codon. (Adapted from a figure graciously provided by Dr. M. Vicente-Manzanares.)

Pecci and colleagues have presented comprehensive data addressing genotype–phenotype correlation.7 Of 93 ADM9 patients, 28% manifested glomerulopathy and 21 of 44 (48%) evaluable pedigrees had glomerulopathy. The mean onset age was 23 years, with 77% having onset before age 30. Of the commonly targeted residues, R702 mutations were associated with the highest incidence of glomerulopathy, with half affected by age 20 and 90% affected by age 40. Strikingly, all individuals with motor domain mutations develop nephritis before age 40, while mutations at 1933 in the non-helical tail were associated with less kidney disease than other mutations in the helical portion of the rod domain.

The molecular mechanisms responsible for the renal findings in ADM9 spectrum disorders are uncertain. Nonmuscle myosin II is expressed in nearly all cells. Nonmuscle myosin IIA is normally expressed in podocytes (at a high level, by immunostaining and in situ hybridization) and mesangial cells (apparently at a somewhat lower level) and, as Sekine and colleagues suggest,1 in certain endothelial cells and most tubular cells. The missense mutations might be associated with haploinsufficiency, which has been shown in platelets with the D1424N mutation,8 or with a dominant-negative phenotype, as has been shown in neutrophils. 9

Relatively few renal biopsies from ADM9 patients have been reported, perhaps in part because of the bleeding diathesis. The reports of renal histology obtained from 14 ADM9 patients have shown a range of findings, summarized in Table 1.1,10–18 To be sure, this compilation may not include all published cases and has major shortcomings: multiple pathologists reading the biopsies, brief descriptions, and varied terminologies. Nevertheless, there may be important lessons that can be learned. Recurring features under light microscopy include mesangial proliferation (6/14), segmental glomerulosclerosis (5/14) and variable tubulointerstitial disease. Recurring features under electron microscopy, which was reported from 11 patients, including glomerular GBM thickening (6/11), splitting (6/11), and attenuation (2/11), so that 9 out of 11 manifested some abnormality of the GBM.

Table 1.

Glomerular findings from renal biopsies obtained from patients with autosomal dominant MYH9 disorders

| Reference | Age | Sex | Continental descent | MYH9 mutation | Serum creatinine | Proteinuria | Light microscopy | Electron microscopy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epstein et al., 197211 | 13 | F | European | R702C | 0.6 mg/dl | 0.2 g/d | Segmental and global glomerulosclerosis, mesangial proliferation | Not performed |

| Clare et al., 197819 | 15 | M | European (Mexican) | ND | 1.2 mg/dl | 14 g/d | Endocapillary proliferation, mesangial expansion, adhesions to Bowman’s capsule, and moderate interstitial fibrosis | GBM thickening, lamellation |

| Peterson et al., 198516 | 23 | M | European | Not determined | End-stage kidney disease | Present | Preserved glomeruli with increased mesangial-cell number and matrix | GBM thickening, focal areas of attenuation; focal podocyte foot process effacement |

| Turi et al., 1992 17 | 14 | M | European | Not determined | 0.8 mg/dl | 1.6–4 g/d | Segmental glomerulosclerosis and diffuse mesangial proliferation | Focal GBM thickening and splitting, foot process effacement |

| Iyori et al., 1995 13 | 14 | F | Asian (Japan) | Not determined | Present | Mild tubular atrophy | Mesangial interposition, GBM splitting | |

| Moxey-Mims, 1999 14 | 7 | M | African | Not determined | 0.6 mg/dl | 1.6 g/m2 | Mild mesangial expansion | Mesangial-cell proliferation and matrix expansion, GBM with variable thickening and basket-weave splitting |

| Naito et al., 1997 15 | 3 | F | Asian (Japan) | Not determined | Not stated | Present | Normal | GBM thickening and reticulation of the lamina densa |

| Naito et al., 1997 15 | 12 | F | Asian (Japan) | Not determined | Normal | Not stated | Mesangial proliferation | Partial splitting of GBM lamina densa |

| Naito et al., 1997 15 | 15 | M | Asian (Japan) | Not determined | Not stated | Nephrotic | Segmental glomerulosclerosis | GBM thinning |

| Ghiggeri et al., 200312 | 49 | M | European | D1424H | 5 mg/dl | Present | Glomerulosclerosis | Nonspecific |

| Ghiggeri et al., 200312 | 24 | F | European | D1424H | Not stated | Present | Normal | Focal segmental foot process effacement |

| Alhindawi et al., 200910 | 10 | M | Asian (Jordan) | Not determined | eGFR 65 ml/min/1.73 m2 | Present | Segmental and global glomerulosclerosis | Not performed |

| Yap et al., 2009 18 | 17 | M | Asian (China) | R702H | 2.3 mg/dl | 4.5 g/d | Global glomerulosclerosis | Not performed |

| Sekine et al., 2010 1 | 9 | F | Asian (Japan) | R702C | 0.4 mg/dl | Present | Mild mesangial-cell proliferation and expansion | Mesangial-cell proliferation and matrix expansion, focal foot process effacement, focal GBM thickening |

| Sekine et al., 2010 1 | 11 | Same case as above | 0.6 mg/dl | Present | Segmental and global glomerulosclerosis | Not stated | ||

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GBM, glomerular basement membrane. Summarized here are the glomerular findings from 15 kidney biopsies obtained from 14 patients, representing all identified reports of kidney biopsies obtained from patients with autosomal dominant MYH9 spectrum disorders (the diagnosis was made clinically or genetically).

Three points are worth making about these pathologic findings and suggest directions for future investigation to define molecular mechanisms.

First, the frequent finding of mesangial hypercellularity is interesting; whether it is due to a direct effect of the abnormal MYH9 protein on mesangial cells is unknown. MYH9 RNA and protein are expressed by mesangial cells, but we have no insight into what pathways, direct or indirect, might lead to proliferation. Indeed, it is not clear that inflammatory-cell infiltration has been excluded as an explanation for the observed hypercellularity.

Second, five biopsies showed segmental glomerulosclerosis, which may be a nonspecific response to mesangial proliferation (two of these patients also showed mesangial proliferation) or to reduced nephron mass (one case with extensive global glomerulosclerosis may represent post-adaptive FSGS). Alternatively, FSGS may represent a manifestation of podocyte injury; indeed, segmental podocyte foot process effacement was present in at least three cases. Whether we label this as FSGS depends on how narrowly or broadly we define this diagnosis. Segmental glomerulosclerosis can be seen in other glomerular diseases, including IgA nephropathy, with primarily mesangial pathology20 and in membranous nephropathy, although this may reflect post-adaptive FSGS.21 Barisoni et al. have proposed a broad definition that makes room under the FSGS tent for segmental glomerulosclerosis with GLA mutations (Fabry disease) and COL4 mutations (Alport syndrome).22 ADM9 spectrum mutations would then fit within the subcategory of genetic FSGS, the common feature of these diseases being podocyte injury that stems from the mutation. It is tempting to link these manifestations of podocyte injury in ADM9 spectrum disorders with the recently discovered association between MYH9 kidney risk alleles, common among African-descent individuals, and FSGS, but in both syndromes our knowledge of disease mechanism is minimal.

Third, the GBM abnormalities, including focal thickening, focal attenuation, and focal splitting, are striking and closely resemble collagen IV mutations in Alport syndrome (and they are not seen in MYH9 kidney risk variant-associated FSGS). These GBM abnormalities raise the possibility that the ADM9 spectrum mutations disrupt the ability of the podocyte to produce extracellular matrix proteins with the appropriate amounts and stoichiometry or the ability to regulate the incorporation of these proteins into the GBM in the process of physiologic remodeling. This is somewhat surprising, as other mutations in podocyte-expressed genes such as NPHS1 (nephrin), NPHS2 (podocin), ACTN4 (α-actinin-4), and TRPC6 are not associated with GBM abnormalities, and may suggest that nonmuscle myosin IIA is particularly engaged in the cellular processes by which podocytes orchestrate GBM assembly and remodeling.

In conclusion, we are just beginning to understand how MYH9 mutations and MYH9 kidney risk variants lead to such diverse glomerular pathology. In vitro studies of podocytes cultured from ADM9 spectrum patients and MYH9 kidney risk variants, either obtained by kidney biopsy or cultured from urine,23 and studies of mice that are heterozygous for a MYH9 -null mutation and mice transgenic for the R702C, D1424N, and E1841K mutations, currently under way (R. Adelstein, personal communication, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health), may shed light on these processes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program. The author thanks Robert Adelstein, Mary Ann Conti, Laura Barisoni, and Cheryl Winkler for critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The author declared no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sekine T, Konno M, Sasaki S, et al. Patients with Epstein –Fechtner syndromes owing to MYH9 R702 mutations develop progressive proteinuric renal disease. Kidney Int. 2010;78:207–214. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley MJ, Jawien W, Ortel TL, et al. Mutation of MYH9, encoding non-muscle myosin heavy chain A, in May-Hegglin anomaly. Nat Genet. 2000;26:106–108. doi: 10.1038/79069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seri M, Cusano R, Gangarossa S, et al. Mutations in MYH9 result in the May-Hegglin anomaly, and Fechtner and Sebastian syndromes. The May-Hegglin/Fechtner Syndrome Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;26:103–105. doi: 10.1038/79063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopp JB, Smith MW, Nelson GW, et al. MYH9 is a major-effect risk gene for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1175–1184. doi: 10.1038/ng.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh N, Nainani N, Arora P, et al. CKD in MYH9-related disorders. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:732–740. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vicente-Manzanares M, Ma X, Adelstein RS, et al. Non-muscle myosin II takes centre stage in cell adhesion and migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:778–790. doi: 10.1038/nrm2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pecci A, Panza E, Pujol-Moix N, et al. Position of nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA (NMMHC-IIA) mutations predicts the natural history of MYH9-related disease. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:409–417. doi: 10.1002/humu.20661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deutsch S, Rideau A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, et al. Asp1424Asn MYH9 mutation results in an unstable protein responsible for the phenotypes in May-Hegglin anomaly/Fechtner syndrome. Blood. 2003;102:529–534. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pecci A, Canobbio I, Balduini A, et al. Pathogenetic mechanisms of hematological abnormalities of patients with MYH9 mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3169–3178. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alhindawi E, Al-Jbour S. Epstein syndrome with rapid progression to end stage renal disease. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2009;20:1076–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein CJ, Sahud MA, Piel CF, et al. Hereditary macrothrombocytopathia, nephritis and deafness. Am J Med. 1972;52:299–310. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(72)90017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghiggeri GM, Caridi G, Magrini U, et al. Genetics, clinical and pathological features of glomerulonephritis associated with mutations of nonmuscle myosin IIA (Fechtner syndrome) Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:95–104. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iyori H, Tokushige A, Ishitoya N, et al. [A case report of Epstein syndrome] (article in Japanese) Nippon Jinzo Gakkai Shi. 1995;37:62–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moxey-Mims MM, Young G, Silverman A, et al. End-stage renal disease in two pediatric patients with Fechtner syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 1999;13:782–786. doi: 10.1007/s004670050700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naito I, Nomura S, Inoue S, et al. Normal distribution of collagen IV in renal basement membranes in Epstein’s syndrome. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:919–922. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.11.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterson LC, Rao KV, Crosson JT, et al. Fechtner syndrome: a variant of Alport’s syndrome with leukocyte inclusions and macrothrombocytopenia. Blood. 1985;65:397–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turi S, Kobor J, Erdos A, et al. Hereditary nephritis, platelet disorders and deafness—Epstein’s syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 1992;6:38–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00856828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yap DY, Tse KC, Chan TM, et al. Epstein syndrome presenting as renal failure in young patients. Ren Fail. 2009;31:582–585. doi: 10.1080/08860220903033708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clare NM, Montiel MM, Lifschitz MD, Bannayan GA. Alport’s syndrome associated with macrothrombopathic thrombocytopenia. Am J Clin Pathol. 1979;72:111–117. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/72.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts NM, Cook HT, Troyanov S, et al. The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: pathology definitions, correlations, and reproducibility. Kidney Int. 2009;76:546–556. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta R, Sharma A, Mahanta PJ, et al. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in idiopathic membranous glomerulonephritis: a clinicopathological and stereological study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:444–449. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barisoni L, Schnaper HW, Kopp JB. Advances in the biology and genetics of the podocytopathies: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:201–216. doi: 10.1043/1543-2165-133.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakairi T, Abe Y, Kajiyama H, et al. Conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell lines established from urine. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F557–F567. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00509.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]