Abstract

Objective To explore the perceived unmet needs among women treated for breast cancer and in whom symptoms and signs indicate the presence of lymphoedema.

Design Population based cross sectional survey with a purpose designed questionnaire (60 items).

Setting Cancer registries of New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia.

Participants 237 women with symptoms and signs indicative of lymphoedema from an initial 1930 eligible women.

Main outcome measure Unmet needs in the previous month across psychological, health system and information, physical and daily living, patient care and support, sexuality needs, body image, and financial domains.

Results The 10 items most commonly identified as a “moderate to high current need” included having their doctor and allied health workers being fully informed about lymphoedema, acknowledge the seriousness of the condition, and be willing to treat it. Women also wanted access to up to date treatments, both mainstream and alternative, and financial assistance for their garments. The three factors that explained most of the variance were: information and support (11 items), which accounted for 49% of the variance; body image and self esteem (seven items; 7% variance); and health system (seven items; 5% variance). Examination of these three factors showed that while the levels of need were generally low, they were common.

Conclusion To address the needs of women with lymphoedema and perhaps to prevent progression of lymphoedema, it is important that practitioners do not dismiss mild symptoms and that women are referred to an appropriate specialist.

Introduction

Lymphoedema is a chronic debilitating condition, which diminishes quality of life and currently cannot be cured. It is characterised by an abnormal accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the at risk arm because of impaired lymphatic transport.1 In Western society, lymphoedema is most commonly seen after treatment for breast cancer. Although the use of sentinel node biopsies has reduced the incidence of lymphoedema,2 recent reports still indicate that about a fifth of treated women develop lymphoedema.1 3 4 5 6 7

Lymphoedema does not necessarily present in a uniform distribution and, particularly in the early stage, might be localised.8 9 For some women lymphoedema becomes intractable, and in the long term the limb can change in size and composition, such that it develops cutaneous thickening and hypercellularity, progressive fibrosis, and pathological deposition of subcutaneous and subfascial adipose tissue.10 Women with lymphoedema have an increased likelihood of psychological distress,11 12 depression, and anxiety.13 14 In addition, the impact of lymphoedema can intrude on many aspects of the women’s lives, including social activities and getting dressed.13 15

Lymphoedema is a chronic condition, which once established requires ongoing management. This chronic condition can affect woman physically and psychosocially, leading potentially to unmet needs. In a study of needs specific to Australian women with breast cancer diagnosed three months to six years previously, almost a quarter of the sample reported coping with lymphoedema was a moderate to high level need.16 The study did not, however, look at what needs were specific to the management of lymphoedema. We explored the perceived unmet needs among women treated for breast cancer and in whom symptoms and signs indicated the presence of lymphoedema.

Method

Participants

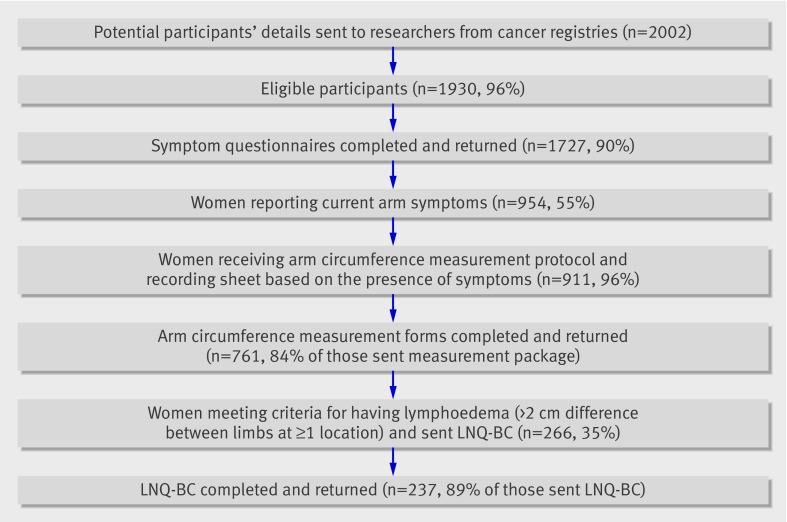

In Australia, all women with a primary diagnosis of breast cancer have their name and diagnosis reported to their respective state cancer registries. Women registered with a primary diagnosis of breast cancer on the New South Wales, Victoria, or South Australia cancer registries three to five years previously and aged 18-70 at time of their diagnosis were eligible to be contacted. Two thousand and two women were approached and gave consent for their details to be forwarded to the investigators. Of these, 72 were ineligible: 59 (2.9%) had bilateral breast cancer, three (<1%) were not currently living in Australia, seven (<1%) could not understand English, and three (<1%) did not return a consent form. From this sample, based on a symptom questionnaire and physical measurement of arm circumference, we identified 267 women as having arm swelling indicative of lymphoedema and sent them a questionnaire (the Lymphoedema Needs Questionnaire-Breast Cancer (LNQ-BC)). Of these women, 237 returned a completed questionnaire. The figure shows the flow of women through the study, and table 1 shows the participants’ characteristics and treatments received. Most women were aged 50 or older at diagnosis. Almost 60% were recruited from New South Wales, and a similar proportion of women were classified (by postcode) as living in a metropolitan area. The most commonly reported treatments were surgical removal of tumour by wide local excision (76%, n=1197) and axillary lymph node dissection (94%, n=1148)).

Number of women participating at each stage of study into unmet needs regarding lymphoedema after treatment for breast cancer (LNQ-BC=Lymphoedema Needs Questionnaire-Breast Cancer)

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics in original cohort and in subgroup of women with lymphoedema after treatment for breast cancer who completed Lymphoedema Needs Questionnaire-Breast Cancer (LNQ-BC). Figures are percentages (number) of women

| Total sample (n=1714) | Completed LNQ – BC (n=237) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years): | ||

| <40 | 9 (146) | 5 (12) |

| 40-49 | 26 (437) | 29 (71) |

| 50-59 | 37 (631) | 39 (94) |

| ≥60 | 29 (500) | 27 (66) |

| Marital status: | ||

| Living with partner | 79 (180) | |

| Living alone | 21 (48) | |

| Metropolitan classification: | ||

| Metropolitan area | 59 (1001) | 49 (119) |

| Non-metropolitan area | 41 (711) | 51 (124) |

| Time since diagnosis of breast cancer (years): | ||

| 3 | 29 (503) | 32 (77) |

| 4 | 34 (580) | 32 (78) |

| 5 | 37 (631) | 36 (88) |

| Medical management of breast cancer*: | ||

| Mastectomy | 44 (706)* | 39 (94) |

| Wide local excision | 76 (1197) | 73 (165) |

| Axillary lymph node dissection | 94 (1585)* | 98 (231) |

| Radiotherapy | 71 (1171)* | 75 (178) |

| Chemotherapy | 67 (1148)* | 53 (126) |

*Up to 8% did not answer question.

Procedure

Letters from the state cancer registries were sent to the medical doctor listed on the cancer registry form for each woman meeting the eligibility criteria. Doctors were asked to exclude their patient if she was physically or emotionally incapable of completing the survey, had insufficient English to complete the questionnaire, or had died, had moved, or was never or was no longer a patient of the doctor.

All women not excluded by the doctor were sent a participant information sheet and consent form, as well as a symptom questionnaire and reply paid envelope. Any woman who did not return the questionnaire within two weeks received one telephone reminder call.

Women who indicated that they were currently experiencing arm swelling, shoulder stiffness, and pain and/or ache or numbness in the arm were asked to have their arm circumference measured by their doctor at their next appointment. If women required a specific appointment for this measurement, they were financially reimbursed. Each arm was measured at five standard points, commencing at the ulnar styloid and moving proximally by 10 cm intervals. Participants were provided with standardised instructions and a recording sheet, a letter for their doctor explaining the study, and a reply paid envelope for them to return their completed measurements to researchers. Women who did not return their arm measurements within three months received one telephone reminder.

To assess unmet needs related to lymphoedema we sent the LNQ-BC to women in whom the arm circumference, on the side of surgery, was 2 cm or more larger than the circumference on the other arm at any of the five standardised points. Women who did not return the questionnaire within two weeks received one reminder telephone call. The time from completion of the initial symptoms questionnaire to completion of the questionnaire was about three months.

Lymphoedema Needs Questionnaire-Breast Cancer (LNQ-BC)

The self administered LNQ-BC questionnaire is based on the reliable and validated Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS), which was designed to measure the perceived needs of adults with a diagnosis of cancer.17 The survey quantifies unmet needs within the previous month across five factor analytically derived domains: psychological, health system and information, physical and daily living, patient care and support, and sexuality.

The lymphoedema needs questionnaire retained each of the questions of the needs survey17 18 and added questions in two additional areas: financial needs and body image needs, to reflect the impact of lymphoedema. The final questions reflected needs identified from within the literature and reports regarding issues faced by women with breast cancer who develop lymphoedema from other needs assessment instruments and from focus groups held with health professionals who provide lymphoedema treatment and women with lymphoedema. The final instrument was piloted in women with lymphoedema to assess ease of understanding, acceptability, and perceived relevance. Response options ranged from “no need-not applicable” to “high need,” as per the needs survey.17 Additionally, women were provided with an option of “some need—but more than 3 months ago.” Sixty questions are related to identification of the women’s needs as well as eight additional questions on disease and treatment and on the women’s background.

Data analysis

We recorded the frequency with which women rated a moderate or high need for each question and ranked the responses to identify the top 10 needs. To identify the domains in which the women had current needs, we recoded the data so that scores indicative of past need, not applicable, or no need were scored 0, low need scored 1, moderate need scored 2, and high need scored 3.

We then performed factor analysis on the 60 applicable items from the lymphoedema needs questionnaire. Principal components model was used to summarise the data with eigenvalues greater than 1. This takes a large number of variables that are possibly correlated and reduces them to a smaller number of uncorrelated variables referred to as “principal components.” We used a varimax rotation and suppressed factor loadings smaller than 0.5. We derived summary scores from the factors by adding the component questionnaire items together (unweighted) and then dividing by the number of items. This summary score was assessed for internal reliability with Cronbach’s α, whereby ≥0.8 was considered reliable.

The summary scores for the three domains that explained most of the variance in the model were then dichotomised to indicate whether or not a woman had some need in that domain. If the averaged score was 0 to 0.49, the summary score for that domain was recoded 0 (that is, no need) and a score of 0.5 to 3 was scored 1 (that is, current need).

We used binary logistic regression to explore to what extent current signs and symptoms of lymphoedema and characteristics of patients predicted the needs of women.

Results

Of the 1713 women who returned the initial symptoms questionnaire, 237 women completed the lymphoedema needs questionnaire, of whom 195 had complete data. These women presented with at least one symptom: 79% (n=182) indicated they currently had swelling; 61% (n=144) had upper limb pain or ache; 37% (n=87) reported shoulder stiffness; and 65% (n=147) reported the presence of numbness. Only 60% (n=130) of this subgroup of women self reported a previous diagnosis of lymphoedema at the time of the first symptom survey. Surprisingly, of the remaining 40% (n=89) who said that they had not received a diagnosis of lymphoedema, 49 reported that they currently had upper limb swelling and 29 women had two or more measurements of arm circumference in the “at risk” limb more than 2 cm larger than in the not at risk limb. At the time of the final assessment in which women completed the lymphoedema needs questionnaire, 90% of women were identified as having lymphoedema, with most having had it for more than two years (table 2).

Table 2.

Symptoms and signs of lymphoedema in women after treatment for breast cancer. Figures are percentages (number) of women

| All women who completed part* | Completed LNQ-BC (n=237) | |

|---|---|---|

| Part A: initial survey | ||

| Current symptoms: | ||

| Swelling | 30 (485)† | 79 (182) |

| Pain/ache | 40 (661)† | 61 (144) |

| Shoulder stiffness | 22 (360)† | 37 (87) |

| Numbness | 45 (746)† | 65 (147) |

| No of current symptoms: | ||

| 0 | 31 (526) | 0 |

| 1 | 21 (260) | 27 (65) |

| 2 | 20 (341) | 28 (67) |

| 3 | 15 (262) | 25 (59) |

| 4 | 13 (226) | 19 (46) |

| Self reported presence of lymphoedema | 22 (330)‡ | 60 (130) † |

| Part B: physical assessment | ||

| No of points in which at risk arm was >2 cm larger than other arm: | ||

| 0 | — | 0 |

| 1 | — | 50 (120) |

| 2 | — | 24 (58) |

| 3 | — | 13 (32) |

| 4 | — | 9 (21) |

| 5 | — | 2 (4) |

LNQ-BC=Lymphoedema Needs Questionnaire-Breast Cancer.

*n=1714 for part A and 752 for part B.

†Up to 5% did not answer question.

‡9-11% did not answer question.

Top 10 individual items: moderate to high current needs

All items within the lymphoedema needs questionnaire were identified by at least one woman as being of some need. Table 3 shows the 10 items most commonly identified as being of “moderate to high need.” Women expressed an unmet need to have their doctor and allied health workers be fully informed about lymphoedema, acknowledge the seriousness of the condition, and be willing to treat it. They also cited an unmet need for accessing up to date treatments, both mainstream and alternative, and financial assistance for their garments.

Table 3.

Current moderate or high unmet needs (individual items) related to lymphoedema in women after treatment for breast cancer

| Rank | Item | Moderate or high need (%) | Domain of need |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Having doctor(s) acknowledge that lymphoedema is a serious condition | 34 | Health system |

| 2 | Having doctor(s) who are fully informed about lymphoedema and its associated problems | 34 | Health system |

| 3 | Having doctor(s) willing to treat lymphoedema | 32 | Health system |

| 4 | Non-recognition or coverage of lymphoedema by Medicare or private health insurance | 30 | Financial |

| 5 | To be informed about alternative treatments for lymphoedema | 30 | Information and support |

| 6 | Having doctor(s)/healthcare professionals willing to follow-up with lymphoedema treatment | 30 | Health system |

| 7 | To have competent, up to date treatment | 29 | Health system |

| 8 | To be given access to assessment programme for early detection of lymphoedema | 29 | Information and support |

| 9 | Having healthcare professionals (such as nurses) fully informed about lymphoedema | 28 | Health system |

| 10 | To be informed of availability of lymphoedema treatment centres | 27 | Information and support |

Domains of current needs

Factor analysis confirmed that the original items from the needs survey used for the lymphoedema needs questionnaire were able to be summarised into similar domains used previously in the needs survey; and the additional items on the lymphoedema needs questionnaire were appropriately categorised into financial needs and body image domains. Factor analysis also showed that one domain accounted for 49% of the variance: this domain comprised 11 questions related to the need for information and support. The second domain accounted for 7% of the variance and identified eight items related to body image and self esteem. The third domain accounted for 5% of the variance and was made up of seven questions related to the health system. Seven other domains were identified but each contributed only 2-4% of the variance. The internal reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s α) of the three top domains ranged from 0.95 to 0.96.

We used the average score, as well as the dichotomised score of need, for each of three domains that contributed most to the variance to obtain an understanding of greatest need (box). Binary logistic regression was undertaken to explain the variance of the dichotomised summary score in each of the three domains. Current symptoms, number of arm circumference measurements (out of a possible five) in which the at risk arm exceeded the other arm, length of time the woman had lymphoedema, and age and whether the cancer was on their dominant side were entered into forward Wald models. Table 4 shows the significant factors identified for each model. The odds of having current needs in each of the three domains that explained most of the variance was increased two to threefold if shoulder stiffness was present. The odds of having a current need for information and support were decreased if the lymphoedema was on their dominant side. The odds of having a current body image need was increased fourfold in women aged <50; and the odds of having a current health system need were increased if ache/pain was also present.

Table 4.

Predictors and odds ratios for each domain of need perceived by women with lymphoedema after treatment for breast cancer

| Domain and variable | No of women | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Wald statistic | df | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information and support | |||||

| Shoulder stiffness: | |||||

| Yes | 70 | 2.83 (1.44 to 5.54) | 8.04 | 1 | 0.002 |

| No | 97 | 1 | |||

| Dominant side affected: | |||||

| Yes | 95 | 0.50 (0.26 to 0.98) | 4.03 | 1 | 0.045 |

| No | 66 | 1 | |||

| Body image and self esteem | |||||

| Shoulder stiffness: | |||||

| Yes | 70 | 2.44 (1.16 to 5.16) | 2.44 | 1 | 0.019 |

| No | 97 | 1 | |||

| Age (years): | |||||

| <50 | 33 | 3.85 (1.49 to 9.90) | 7.79 | 1 | 0.005 |

| 50-59 | 61 | 1.52 (63 to 3.68) | 0.87 | 1 | 0.350 |

| ≥60 | 68 | 1 | — | 2 | 0.018 |

| Health system | |||||

| Shoulder stiffness: | |||||

| Yes | 68 | 2.27 (1.14 to 4.53) | 5.42 | 1 | 0.020 |

| No | 97 | 1 | |||

| Ache: | |||||

| Yes | 99 | 2.30 (1.12 to 4.70) | 5.19 | 1 | 0.023 |

| No | 61 | 1 | |||

Current needs (domains)

Information and support (11 items) (variance 49.1%, Cronbach’s α 0.95, mean (SD) score 0.61 (0.86), frequency 35.5%)

To provide family members with information about lymphoedema

To be fully informed about lymphoedema support groups in the area

To be given information (written, diagrams, drawings) about aspects of managing lymphoedema

To be adequately informed about the treatment options (benefits and side effects) for lymphoedema before you choose to have them

To be informed about alternative treatment for lymphoedema

To be informed of the availability of lymphoedema treatment centres

To be given a full explanation of those tests and treatments for which you would like explanations

To receive consistent lymphoedema treatment information that does not vary between sources

To be fully informed about the causes of lymphoedema

To have access to vocational assistance/counselling for help in adjusting to having lymphoedema

Coping with frustration with the lack of assistance in dealing with the lymphoedema

Body image (8 items) (variance 7.3%, Cronbach’s α 0.96, mean (SD) score 0.39 (0.73), frequency 25%)

Coping with embarrassment caused by the appearance of the affected arm

Coping with high levels of self consciousness because of lymphoedema

Availability of clothes to hide arm

Accepting changes in your appearance

Coping with anxiety when going out because of the appearance of your arm

Coping with the loss of confidence because of lymphoedema

Avoiding social situations because of lymphoedema

Coping with reduced self esteem because of lymphoedema

Health system (7 items) (variance 4.7%, Cronbach’s α 0.96, mean (SD) score 0.90 (1.14), frequency 41.2%)

Avoiding social situations because of lymphoedema

Having doctor(s) willing to treat lymphoedema

Having doctor(s)/healthcare professionals willing to follow-up your lymphoedema treatment

Having doctor(s) who are fully informed about lymphoedema and its associated problems

Having healthcare professionals (such as nurses) fully informed about lymphoedema

To have competent, up to date treatment

Non-recognition or coverage of lymphoedema by Medicare or private health insurance

Discussion

Principal findings

A high percentage of women expressed current needs related to lymphoedema three to five years after their initial diagnosis of breast cancer. These needs were for their doctor and allied health worker to have knowledge about lymphoedema, treat it as a serious condition, and be willing to follow them with respect to treatment. This need was reflected both in the top 10 ranked individual needs as well as in the domains that explained most of the variance.

Strengths and weaknesses

This large population based study investigated the needs of women with lymphoedema secondary to treatment for breast cancer. Studies involving women with lymphoedema are usually small and often reflect the views of those who are attending clinics,13 14 15 19 20 21 thereby introducing a bias. In addition, the recruitment strategies for many of the previous studies result in them being weighted toward women with moderate to severe lymphoedema, even though most women present with mild lymphoedema.5 We had no presupposition regarding the needs of women with lymphoedema, even though the literature suggests strong psychosocial need and other studies of patients with cancer indicated that their needs were in the psychological and physical domains.

There were weaknesses associated with the current project. Firstly, we assumed that women who responded to the needs questionnaire had lymphoedema. This study was designed to filter out women treated for breast cancer who did not have lymphoedema. We expected that the women who indicated the presence of arm/shoulder symptoms and in whom there was a difference between limbs would have lymphoedema. Examination of the data suggests that this filter might not have worked perfectly. About 40% of women in whom the “at risk” limb was measured as larger than the limb on the unaffected side reported not having a previous diagnosis of lymphoedema (n=86); however, 49/86 women indicated that their arm was swollen. An alternative explanation could be that the filter worked well but women did not know what lymphoedema is.

The second weakness of the study was that women were not asked to rate the severity of their swelling or their symptoms, and we therefore were unable to categorise them according to the severity of their lymphoedema. This limitation prevented us from examining the needs of women with mild lymphoedema compared with those with severe lymphoedema. The third weakness of this study is its focus only on arm lymphoedema. We did not examine the presence of swelling in the hand and trunk region (that is, breast and anterior and posterior chest) on the side of surgery.

Possible explanations and implications for clinicians

Within the first few years after treatment for breast cancer, women can develop lymphoedema. For most women, the swelling is likely to be noticeable only to themselves.5 The physiological changes, however, can be detected by bioimpedance spectroscopy, which quantifies the extracellular fluid rather than the limb volume.22 23 These early changes are associated with symptoms and increased distress compared with those without lymphoedema.5 8 24 25 Routine use of bioimpedance spectroscopy preoperatively and at routine follow-up visits can identify early lymphoedema changes that might not be detected by measuring arm circumference and arm volume, thus alleviating some distress associated with developing lymphoedema. In our study, it was the presence of shoulder stiffness and not arm swelling that was associated with current needs. For these women, shoulder stiffness might have been directly related to the presence of lymphoedema, arisen secondarily through protectiveness of the affected limb,26 or was, in fact, unrelated to the swelling.

About 35% of women reported some need for information and support. Several issues could contribute to this need. Firstly is the timing of when information is provided. Women might be overloaded around the time of diagnosis and treatment of the cancer; they are unaware that they have been provided with information on topics such as lymphoedema.26 27 As it is assumed that women have been provided with information, no further follow-up occurs. It seems that women might need to be informed of issues such as lymphoedema at several points after treatment for breast cancer and not simply on one occasion. Secondly, the information might be available but has not been accessed by woman with lymphoedema. Factual information such as location of lymphoedema specialists and support groups can be provided in a range of formats, electronically and in print. Health practitioners to whom women turn for advice need to be aware of what resources are available and, when possible, refer women to specialist lymphoedema practitioners, who are skilled in the assessment and management of this condition, and who are most likely to be up to date with the evidence that supports clinical practice.

Until quite recently, the information provided to women was almost entirely based on expert opinion. It is only recently that empirical studies have been undertaken to evaluate the clinical course of lymphoedema in the first few years after its presentation,28 29 30 beliefs about causes of lymphoedema,31 32 and management.33 Some of the findings from these recent studies conflict with what women have been told, based on expert opinion. For example, the message women have received is that they are not to use their at risk or affected arm for vigorous activity,26 yet Schmitz and her colleagues clearly showed that physical activity—such as progressive resistance training—neither causes or exacerbates lymphoedema but does decrease symptoms.32 There is still a paucity of well designed studies on management strategies, including alternative treatments. In addition, there are no studies that document the long term clinical course of this condition and its long term impact on women who survive breast cancer. Thus, some issues within this domain can be addressed, but studies are required to inform other aspects.

Women perceive that lymphoedema is not considered as a serious illness by their doctor and other health workers, a finding previously noted in smaller studies.13 19 27 34 While women might have continual review for cancer recurrence by their breast surgeon three to five years after diagnosis, they might not return to them for issues related to lymphoedema. Women will also be under the care of their family doctor, and it is from this doctor they might seek advice regarding their lymphoedema. Because most women will have minimal overt signs of swelling at this stage, the symptoms they experience, including shoulder stiffness and ache, might be dismissed. Yet it is currently believed, although not proved, that intervention at the earliest opportunity is the most effective. To address the needs of women with lymphoedema and perhaps prevent progression, it is important that mild symptoms are not dismissed and that women are referred to the appropriate specialist.

The other interesting finding was related to the perceived need for information at the time of their breast surgery about lymphoedema and its cause. As part of routine care, at least in the major cancer treatment centres, information about lymphoedema is routinely provided to women at the time of surgery. As noted previously, women might not recognise that they have received the relevant information,26 35 or the information might have been given to them at a time when they feel overloaded with information related to their cancer.36 Our study suggests, in conjunction with previous work, that women who are at high risk for lymphoedema might need to hear about risks and treatment on more than one occasion. Women might benefit from formal allied health and/or medical follow-up some time after surgery to clearly explain the facts about this condition.

Unanswered questions and future research

Our study has shown that the levels of needs of these women are low but common with respect to the need for information, acknowledgement by those in the health system of the seriousness of their condition, and body image and self esteem. Only shoulder stiffness was identified as a predictor of need. It would be useful to determine whether the needs of women with lymphoedema depend on the severity of lymphoedema and the factors that might moderate the level of their needs. While it might be convenient to categorise women in future studies on the basis of the magnitude of swelling, there is some evidence that this might not be a helpful classification.12 37 Other factors such as symptoms arising from lymphoedema—for example, shoulder stiffness—or time since presentation of lymphoedema might be of greater importance.

In conclusion, women with lymphoedema three to five years after surgery for breast cancer do have unmet needs. In contrast with psychological and physical needs related to their cancer, their needs related to lymphoedema are for information and support, particularly from their doctor and allied health workers.

What is already known on this topic

Women treated for breast cancer have moderate to high needs with respect to coping with lymphoedema

What this study adds

Three to five years after treatment for breast cancer, women with lymphoedema are in need of information about their lymphoedema and support in its management, particularly from their doctor and allied health workers

We thank all the participants who made this study possible.

Contributors: AG was responsible for study concept and design and for obtaining funding for the project. FS acquired the data. SK, DB, and TL were responsible for analysis and interpretation of data. All authors were responsible for drafting and revising the manuscript. AG and SK gave administrative, technical, and material support. SK is guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by a grant in aid from the National Breast Cancer Foundation; SK is funded by the National Breast Cancer Foundation.

Role of the sponsor: NBCF had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, analysis, interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the University of Newcastle and NSW Cancer Institute, and all women provided written informed consent.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;342:d3442

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Lymphoedema Needs Questionnaire-Breast Cancer (LNQ-BC)

References

- 1.Lawenda BD, Mondry TE, Johnstone PA. Lymphedema: a primer on the identification and management of a chronic condition in oncologic treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:8-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg JI, Wiechmann LI, Riedel ER, Morrow M, Van Zee KJ. Morbidity of sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer: the relationship between the number of excised lymph nodes and lymphedema. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:3278-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armer JM, Stewart BR, Shook RP. 30-month post-breast cancer treatment lymphoedema. J Lymphoedema 2009;4:14-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres Lacomba M, Yuste Sanchez MJ, Zapico Goni A, Prieto Merino D, Mayoral del Moral O, Cerezo Tellez E, et al. Effectiveness of early physiotherapy to prevent lymphoedema after surgery for breast cancer: randomised, single blinded, clinical trial. BMJ 2010;340:b5396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norman SA, Localio AR, Potashnik SL, Simoes Torpey HA, Kallan MJ, Weber AL, et al. Lymphedema in breast cancer survivors: incidence, degree, time course, treatment, and symptoms. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:390-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meeske KA, Sullivan-Halley J, Smith AW, McTiernan A, Baumgartner KB, Harlan LC, et al. Risk factors for arm lymphedema following breast cancer diagnosis in black women and white women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;113:383-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stout Gergich NL, Pfalzer LA, McGarvey C, Springer B, Gerber LH, Soballe P. Preoperative assessment enables the early diagnosis and successful treatment of lymphedema. Cancer 2008;112:2809-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliveri JM, Day JM, Alfano CM, Herndon JE 2nd, Katz ML, Bittoni MA, et al. Arm/hand swelling and perceived functioning among breast cancer survivors 12 years post-diagnosis: CALGB 79804. J Cancer Surviv 2008;2:233-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanton AW, Mellor RH, Cook GJ, Svensson WE, Peters AM, Levick JR, et al. Impairment of lymph drainage in subfascial compartment of forearm in breast cancer-related lymphedema. Lymphat Res Biol 2003;1:121-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brorson H, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Karlsson MK. Breast cancer-related chronic arm lymphedema is associated with excess adipose and muscle tissue. Lymphat Res Biol 2009;7:3-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maunsell E, Brisson J, Deschenes L. Arm problems and psychological distress after surgery for breast cancer. Can J Surg 1993;36:315-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Passik SD, McDonald MV. Psychosocial aspects of upper extremity lymphedema in women treated for breast carcinoma. Cancer 1998;83:2817-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter BJ. Women’s experiences of lymphedema. Oncol Nurs Forum 1997;24:875-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tobin MB, Lacey HJ, Meyer L, Mortimer PS. The psychological morbidity of breast cancer-related arm swelling. Psychological morbidity of lymphoedema. Cancer 1993;72:3248-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woods M, Tobin M, Mortimer P. The psychosocial morbidity of breast cancer patients with lymphoedema. Cancer Nurs 1995;18:467-71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girgis A, Boyes A, Sanson-Fisher RW, Burrows S. Perceived needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: rural versus urban location. Aust N Z J Public Health 2000;24:166-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonevski B, Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Burton L, Cook P, Boyes A. Evaluation of an instrument to assess the needs of patients with cancer. Supportive Care Review Group. Cancer 2000;88:217-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Boyes A, Bonevski, B, Burton L, Cook P. The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Supportive Care Review Group. Cancer 2000;88:226-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenslade MV, House CJ. Living with lymphedema: a qualitative study of women’s perspectives on prevention and management following breast cancer-related treatment. Can Oncol Nurs J 2006;16:165-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansson K, Holmstrom H, Nilsson I, Ingvar C, Albertsson M, Ekdahl C. Breast cancer patients’ experiences of lymphoedema. Scand J Caring Sci 2003;17:35-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Towers A, Carnevale FA, Baker ME. The psychosocial effects of cancer-related lymphedema. J Palliat Care 2008;24:134-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornish BH, Bunce IH, Ward LC, Jones LC, Thomas BJ. Bioelectrical impedance for monitoring the efficacy of lymphoedema treatment programmes. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1996;38:169-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornish BH, Chapman M, Thomas BJ, Ward LC, Bunce IH, Hirst C. Early diagnosis of lymphedema in postsurgery breast cancer patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;904:571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes S, Janda M, Cornish B, Battistuta D, Newman B. Lymphedema secondary to breast cancer: how choice of measure influences diagnosis, prevalence, and identifiable risk factors. Lymphology 2008;41:18-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cormier JN, Xing Y, Zaniletti I, Askew RL, Stewart BR, Armer JM. Minimal limb volume change has a significant impact on breast cancer survivors. Lymphology 2009;42:161-75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee TS, Kilbreath SL, Sullivan G, Refshauge KM, Beith JM, Harris LM. Factors that affect intention to avoid strenuous arm activity after breast cancer surgery. Oncol Nurs Forum 2009;36:454-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee TS, Kilbreath SL, Sullivan G, Regshauge KM, Beith JM. Patient perceptions of arm care and exercise advice after breast cancer surgery. Oncol Nurs Forum 2010;37:85-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shih YCT, Xu Y, Cormier JN, Giordano S, Ridner SH, Buchholz TA, et al. Incidence, treatment costs, and complications of lymphedema after breast cancer among women of working age: a 2-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2007-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norman SA, Localio AR, Potashnik SL, Simoe Torpey HA, Kallan MJ, Weber AL, et al. Lymphedema in breast cancer survivors: incidence, degree, time course, treatment, and symptoms. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:390-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayes SC, Janda M, Cornish B, Battistuta D, Newman B. Lymphedema after breast cancer: incidence, risk factors, and effect on upper body function. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3536-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kilbreath S, Ward C, Lane K, McNeely M, Dylke ES, Refshauge KM. Effect of air travel on lymphedema risk in women with history of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010;120:649-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, Cheville A, Smith R, Lewis-Grant L, et al. Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer-related lymphedema. N Engl J Med 2009;361:664-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNeely ML, Peddle CJ, Yurick JL, Dayes IS, Mackey JR. Conservative and dietary interventions for cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer 2011;117:1136-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins LG, Nash R, Round T, Newman B. Perceptions of upper-body problems during recovery from breast cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 2004;12:106-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee TS, Kilbreath SL, Sullivan G, Refshauge KM, Beith JM. The development of an arm activity survey for breast cancer survivors using the Protection Motivation Theory. BMC Cancer 2007;7:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunn SM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, Jones QJ, Sheldon JS, Taylor JJ, et al. General information tapes inhibit recall of the cancer consultation. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:2279-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman ML, Brennan M, Passik S. Lymphedema complicated by pain and psychological distress: a case with complex treatment needs. J Pain Symptom Manage 1996;12:376-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Lymphoedema Needs Questionnaire-Breast Cancer (LNQ-BC)