Abstract

Background:

Metastases to the pancreas are an uncommon cause of pancreatic masses seen on endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA). The purpose of this study is to retrospectively review the cytomorphology, clinical findings, and results of ancillary studies in a large series of these unusual cases.

Materials and Methods:

We searched our institution's pathology database for EUS-guided FNAs of the pancreas that were diagnostic of metastatic tumor over a 5-year period. The final cytologic diagnosis, results of ancillary studies, corresponding histological material, and clinical follow-up data were reviewed in these cases.

Results:

A total of 1172 pancreatic EUS-guided FNAs were identified, of which 25 cases (2.1%) had a confirmed diagnosis of a pancreatic metastasis. This included 12 (48%) cases of renal cell carcinoma, 3 (12%) melanomas, 3 (12%) small cell carcinomas, and 7 (28%) other malignancies. In these metastatic tumors involving the pancreas, 20 (80%) of the lesions were solitary. Four (16%) cases had no prior history of malignancy. The average time to diagnosis of pancreatic metastasis was 5.3 years. Immunohistochemistry and special stains were performed in 22 (88%) and 9 (36%) cases, respectively.

Conclusions:

Our data shows that although metastases to the pancreas are rare, they can present as a solitary mass many years after the primary malignancy is diagnosed and can even be the first manifestation of an extrapancreatic primary in a small number of cases. It is important to consider the possibility of a metastatic lesion in the pancreas because this may require a different management than a primary pancreatic tumor.

Keywords: Cytology, endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration, pancreatic metastases

INTRODUCTION

Since it was first reported by Chang et al, in 1994,[1] endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the pancreas has become a popular technique for the diagnosis and staging of cystic and solid lesions of the pancreas because it is relatively safe,[2] accurate,[3] and cost-effective.[4] Thus, this diagnostic modality has become essential in the management of patients with symptomatic or incidentally discovered pancreatic masses. EUS-guided FNA usually serves to confirm the diagnosis of a primary pancreatic malignancy. Therefore, it is not surprising that most reports focus on the more common primary pancreatic cystic and solid neoplasms, with little attention given to metastatic lesions. In the literature, metastases comprise at least 2% of pancreatic tumors.[5] These metastases arise from a diverse spectrum of malignancies, including sarcomas,[6] Merkel cell carcinoma,[7] squamous cell carcinoma,[8] cardiac rhabdomyosarcoma,[9] ovarian mixed müllerian tumor,[10] melanoma,[11] and phyllodes tumor.[12] In such cases, accurate diagnosis is extremely important because treatment frequently differs.[13,14] We review the cases of pancreatic metastases diagnosed by EUS-guided FNA at our institution in order to characterize the clinico-radiologic features, cytomorphology, results of ancillary studies, and clinical follow-up data of these unusual tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

During a period of 60 months, between March 2005 and April 2010, 1172 pancreatic EUS-guided FNAs were performed at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. These cases were identified by searching our institution's CoPath computer database for the word ′pancreas′ in the final diagnosis of FNA biopsies. A case was included if the cytology report contained a diagnosis of metastatic tumor that was confirmed by immunohistochemical (IHC) studies or subsequent histologic correlation. Cases of lymphoma were excluded. The cytomorphology, IHC studies, available clinical information, and histological follow-up were then retrospectively reviewed.

Cytomorphological assessment

FNA biopsies were performed by a gastrointestinal physician with specialized training in the endoscopic ultrasound-guided technique. The Olympus GF-UE160-AL5 radial-array video gastroscope (Olympus Imaging America Inc., Center Valley, PA) was used in all cases. For each case, immediate on-site adequacy assessment and interpretation by a cytopathologist allowed for appropriate triage of the specimen. This involved examination of a Diff-Quik™ (Protocol Hema 3, Fisher Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) stained smear from each FNA pass. Material was used to make air-dried and 95% alcohol-fixed smears. Additional material was formalin fixed for a cell block preparation. The number of FNA passes varied depending upon the adequacy of the sampled material and patient toleration of the procedure. At the time of final interpretation, Papanicolaou and Diff-Quik stained smears and hematoxylin and eosin (HandE) stained sections from the formalin-fixed cell block were examined and evaluated in conjunction with the results from ancillary studies.

Ancillary studies

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on deparaffinized, formalin-fixed cell block sections using a variety of different antibodies on the Ventana Benchmark® XT system (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ). For a large majority of cases, the following immunostains were performed to characterize the cells and rule out a primary neoplasm: CK7 (clone OV-TL 12/30, monoclonal antibody; 1:200 dilution; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), CK20 (clone Ks20.8, monoclonal antibody; 1:50 dilution; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), CA19-9 (clone 121SLE, monoclonal antibody; pre-dilute; Ventana, Tucson, AZ), and CEA (clone TF 3H8-1, monoclonal antibody; pre-dilute; Ventana, Tucson, AZ). Renal cell carcinomas, when suspected, were most often stained with a combination of CD10 (clone 56C6, monoclonal antibody; pre-dilute; Ventana, Tucson, AZ); vimentin (clone V9, monoclonal antibody; pre-dilute; Ventana, Tucson, AZ); pan-keratin (clone 80, monoclonal antibody; 1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA); carbonic anhydrase 9 (clone n/a, polyclonal antibody; 1:1000; Leica, Bannockburn, IL); and RCC (clone PN-15, monoclonal antibody; pre-dilute; Ventana, Tucson, AZ). Small cell and neuroendocrine neoplasms were examined with CD56 (clone 123C3.D5, monoclonal antibody; pre-dilute; Cell Marque, Rocklin, California); synaptophysin (clone n/a, polyclonal antibody; pre-dilute; Cell Marque, Rocklin, California); and chromogranin (clone LK2H10, monoclonal antibody; pre-dilute; Ventana, Tucson, AZ). Other IHC stains were performed as indicated, depending upon the case. All stains were performed according to the standard avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method. Briefly, sections were submitted to heat-induced antigen retrieval in the presence of CC1 (Cell Conditioner 1, Ventana Medical Systems, AZ, USA) using an automated tissue immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, AZ, USA), with the appropriate positive and negative controls on the same or an accompanying slide.

RESULTS

Of the total 1172 EUS-guided FNAs of the pancreas, 25 cases (2.1%) of metastases were identified. The average age of the patients was 61 years (range: 40-80 years). There were 14 females and 11 males. Twenty-one cases (84%) had a previous diagnosis of malignancy of the same type. The mean time between the initial diagnosis of cancer and the development of a pancreatic metastasis was 5.3 years (range: 0-19 years). However, in four (16%) cases the EUS-guided FNAs occurred in patients with no prior diagnosis of malignancy. Twenty (80%) of the lesions were solitary, while in five (20%) cases there were multiple lesions. Nine (36%) FNAs were from the head of the pancreas, six (24%) from the tail, two (8%) from the body, and eight (32%) from an unknown or uncertain location. Seven (28%) patients underwent surgical removal of the tumor by pancreatectomy. All cases were confirmed on histological follow-up, IHC stains, and/or clinical follow-up review.

The final cytological diagnosis was positive for malignancy in all but two (92%) technically limited cases of conventional renal cell carcinoma. A specific malignancy was diagnosed in 18 cases (72%). Overall, the most common histological type was renal cell carcinoma (RCC), seen in twelve (48%) cases. The other histologic subtypes included malignant melanoma (3 cases, 12%); small cell carcinoma (3 cases, 12%); and renal leiomyosarcoma, prostatic adenocarcinoma, breast adenocarcinoma, gastric adenocarcinoma, esophageal adenocarcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma, and a non-primary neuroendocrine tumor (1 case each). The four cases that presented as a mass in the pancreas with no prior history of malignancy included a case of prostatic carcinoma, a small cell carcinoma of the lung, a renal cell carcinoma, and an extrapancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. IHC on the cell block material was utilized in 22 cases (88%). Special stains such as PAS, PASD, and mucicarmine were performed in nine (36%) cases. See Table 1 for a list of this information for each case.

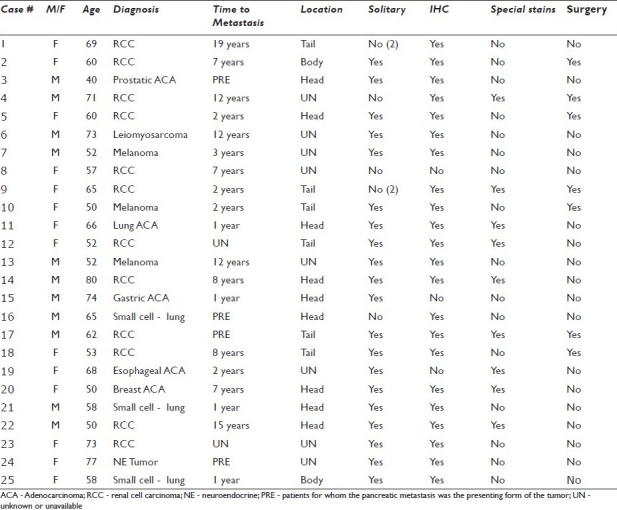

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic findings in 25 cases of metastases in EUS-guided FNA of the pancreas

DISCUSSION

It is well known that primary neoplasms of the pancreas are more common than metastatic tumors. Although metastases to the pancreas are rare, our data characterizes the cytomorphological and clinical findings in a large series of patients. Our findings demonstrate that metastases to the pancreas frequently present in older patients as a solitary mass, many years after the diagnosis of a primary malignancy. Although the majority of lesions were found in the head of the pancreas in our series, they may also be seen in the body and tail as has been described by Sellner et al. in a review of 236 RCC resection specimens.[15] In a significant subset (16%) of our cases a pancreatic mass was the first clinically recognized manifestation of an extrapancreatic primary [Figure 1]. In two suspicious cases of conventional renal cell carcinoma, material for ancillary studies was inadequate and a diagnosis of ‘atypical’ was rendered. These observations illustrate the importance of acquiring material for cell block in cases suspicious for a metastasis to the pancreas.

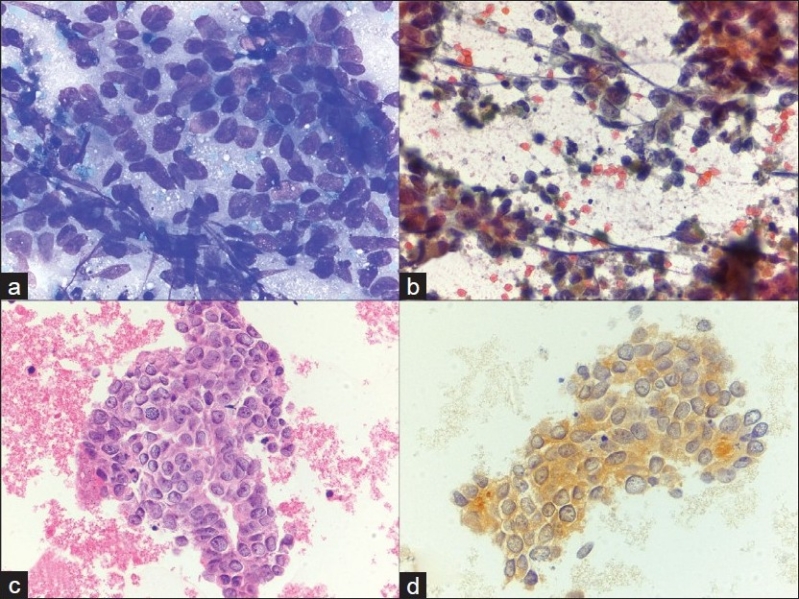

Figure 1.

Metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. a) Many pleomorphic epithelioid cells with increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios are occasionally arranged in an acinar-like formation (40×, Diff-Quik stain); b) Eccentric nuclei with highly prominent macronucleoli, coarsely clumped chromatin, and irregular outlines are highlighted (40×, Papanicolaou stain); c) Cell block material demonstrates a gland like configuration with prominent nucleoli (H and E, 20×), d) A PSA immunostain is expressed, supporting the diagnosis of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma (40×, immuno)

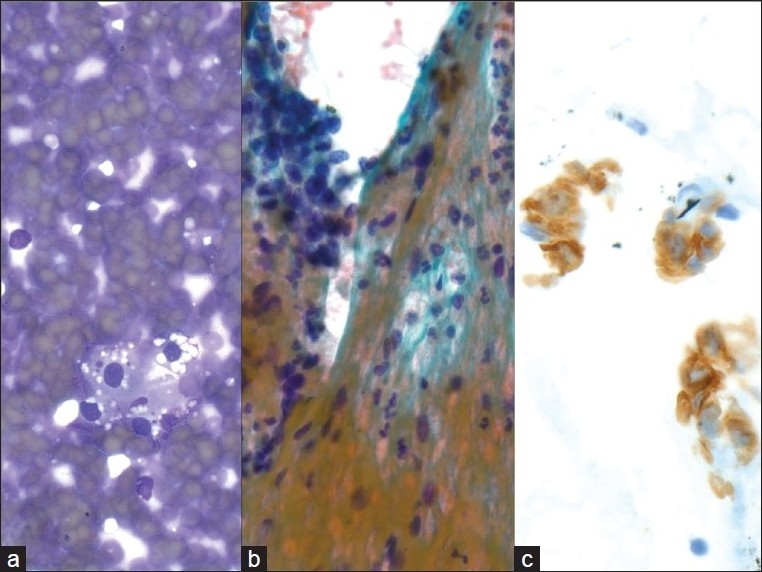

In a survey of 4955 adult autopsies, Adsay et al. described a rate of metastasis to the pancreas of 3.83% and a significantly different distribution of metastatic neoplasms, with lung and gastrointestinal tumors comprising by far the largest proportion.[16] The study also showed, as might be expected, a higher rate of new diagnoses (43%). Our data demonstrates a similar rate of metastasis (2.1%), but RCC was the most common metastatic tumor type in our series. This finding is similar to that reported in other FNA and resection studies examining metastases to the pancreas.[5,17,18] These studies, like ours, may select for tumors with limited spread through the body and/or solitary lesions amenable to resection, as is characteristic of RCC.[16,19] Our data also shows that metastatic RCC may occur many years (as much as 19 years, according to our data) after a primary diagnosis.[16–18] These characteristics of RCC may mimic a primary pancreatic tumor and may explain why metastatic RCCs were so common in our series of pancreatic metastases diagnosed by EUS-FNA. The biologic basis of this distinct and well-documented behavior of RCC is controversial and poorly understood. Sellner et al. hypothesize that hematogenous spread and a hospitable pancreatic environment, in combination with the particular biology of RCC, may explain the relatively more common occurrence of this tumor.[15] Although RCCs may have a broad range of cytologic appearances, the features of clear cell (conventional type) RCC are distinctive and include abundant vacuolated cytoplasm with ‘punched out’ holes and round uniform nuclei with prominent nucleoli [Figure 2]. The tumor cells are also frequently seen in association with small blood vessels or basement membrane material. It is important to distinguish this type of RCC from other entities, including primary pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with clear cell (or foamy) change, well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors with clear cell changes, and other rare clear cell neoplasms, such as PEComas or clear cell ‘sugar’ tumors. In contrast, primary ductal adenocarcinomas of the pancreas are generally characterized by increased cellular pleomorphism, nuclear membrane irregularities, and coarse chromatin.

Figure 2.

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. a) Cluster of round cells, with uniform nuclei and vacuolated cytoplasm with ‘punched out’ holes (40×, Diff-Quik stain), b) Large, cohesive clusters of uniform epithelial cells are seen traveling with endothelial cells and stromal components (40×, Papanicolaou stain), c) An RCC immunostain is focally expressed, supporting the diagnosis of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (40×, immuno)

IHC stains are helpful in that nearly all pancreatic adenocarcinomas express CK7 as well as PASD, CK19, CEA, and CA19-9.[20] In comparison, RCC is typically negative for CK7, except for many papillary and chromophobe subtypes.[21] RCCs do not usually stain with PASD and are mostly negative for CEA.[22] Vimentin is typically expressed by RCC, but negative in most pancreatic adenocarcinomas.[23] Immunostains can also distinguish RCC from ambiguous neuroendocrine tumors (positive for synaptophysin, CD56, and chromogranin) and PEComas (positive for HMB45). The papillary subtype of RCC, frequently seen accompanied by foamy macrophages and fibrovascular cores, is also a potential pitfall. Careful interpretation of IHC stains is essential since vimentin and CD10, for instance, can stain positively in solid pseudopapillary tumor, which may be in the differential. In these cases, beta-catenin, with nuclear expression in nearly all solid pseudopapillary tumors and cytoplasmic or membranous expression in RCC, is of particularly high utility.[24] Lastly, sarcomatoid dedifferentiation of a RCC should be considered whenever a spindle cell neoplasm or poorly differentiated tumor is present in the pancreas.

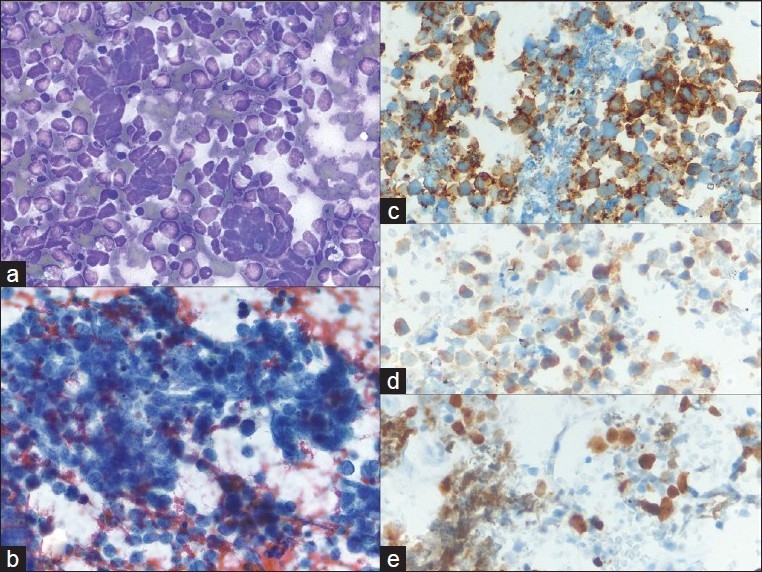

Small cell carcinoma metastatic to the pancreas was another metastatic tumor that was relatively common in our series. The cytomorphological findings in these cases overlap with that of other small round blue cell tumors, including lymphomas, sarcomas (i.e., Ewing/PNET, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, and desmoplastic small round cell tumor), and primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the pancreas. The features seen in small cell carcinoma include stippled, ‘salt-and-pepper’ chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, nuclear molding, crush artifact, and loosely cohesive cells in an apoptotic or necrotic background [Figure 3]. Although TTF-1 is useful for determining a pulmonary origin for adenocarcinoma, it has been reported in up to 80% of extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas[25] and thus does not differentiate between primary and metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma. Small cell carcinoma of the pancreas is an entity with very few reported cases in the literature and therefore the presence of a tumor with the above described cytomorphology should raise suspicion for an extrapancreatic primary.

Figure 3.

Metastatic small cell carcinoma of the lung; a) Many loose, small, mildly pleomorphic cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios are seen. Some cells are densely crowded into small clusters with nuclear molding (40×, Diff-Quik stain); b) Round nuclear outlines, absent or minimal nucleoli, and smooth, dark chromatin (40×, Papanicolaou stain); c-e) CD56, synaptophysin and Ki67 are expressed, supporting the diagnosis of metastatic small cell carcinoma (40×, immuno)

In summary, careful scrutiny of the clinical record and radiographic studies is essential when determining the origin of a small cell carcinoma since the morphologic and IHC appearances of primary and metastatic tumors are typically equivalent. If a history of a primary malignancy is available, review of the histology is necessary and molecular studies such as loss of heterozygosity analysis can occasionally be informative. Recent examination of PAX8 immunohistochemistry suggests a differential staining pattern in pulmonary vs gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. However, further study is required to more definitively characterize the utility of PAX8 in these instances.[26] Melanoma was also a common cause of metastasis to the pancreas in our study. It usually shows a pleomorphic single cell pattern and scattered dark pigment deposition by cytomorphology. When presented with a poorly differentiated neoplasm and a specimen composed of pleomorphic single cells (e.g. poorly differentiated carcinoma, sarcoma, lymphoma),[27] IHC stains for melanocytic markers (melanin A, HMB45, tyrosinase, and S100) and keratins are essential [Figure 4]. These stains are reasonably specific and can help avoid an error and confirm the cytomorphologic impression of melanoma.

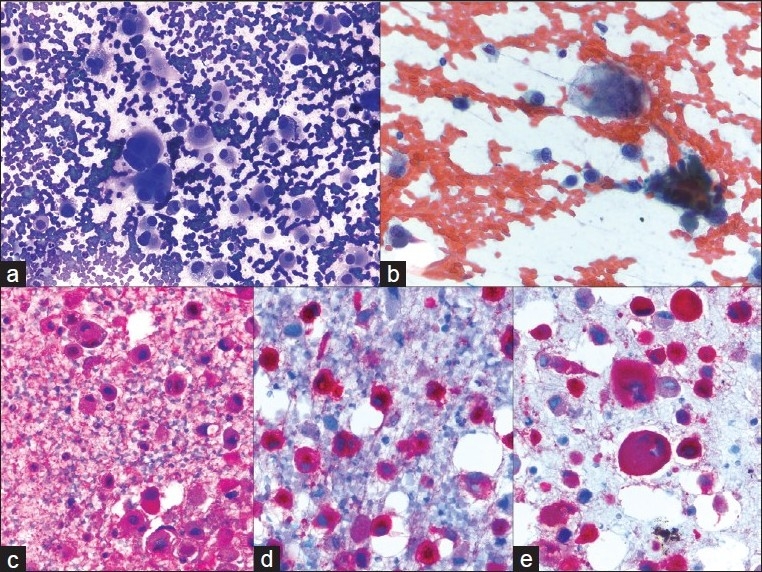

Figure 4.

Metastatic melanoma; a) A very loose collection of giant cells, multinucleated cells and large pleomorphic cells with a plasmacytoid appearance (40×, Diff-Quik stain); b) Hyperchromatic, coarsely clumped nuclear chromatin with very irregular nuclear outlines. The cytoplasm contains dusty pigmentation (40×, Papanicolaou stain); c-e) S-100, HMB45, and melanin A are strongly expressed (40×, immuno)

The results of this study are important due to the increasing use of EUS-guided FNA in the preoperative evaluation of pancreatic masses for pathologic diagnosis and because of the paucity of data in the literature characterizing metastases seen in these types of specimens. Thus, awareness of the spectrum of metastases seen in the pancreas, in addition to knowledge of the clinicopathologic findings and potential pitfalls, is important for cytopathologists analyzing and triaging these difficult specimens.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data shows that metastatic tumors may rarely occur in the pancreas. They can occur as solitary masses, often in the head of the pancreas, and may occur in patients without a known history of malignancy, thus clinically resembling a pancreatic primary. Cytopathologists need to be aware of this unusual possibility of a metastasis in the pancreas because a different management approach may be necessary and, typically, the staging and prognosis are different.[28,29] The combination of detailed clinical history, imaging findings, and cytomorphological features, in addition to the use of immunohistochemistry, can help confirm a diagnosis and thus allow prompt initiation of appropriate treatment.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE. All authors are responsible for the conception of this study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) (or its equivalent) of all the institutions associated with this study. Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL / PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model(authors are blinded for reviewers and reviewers are blinded for authors)through automatic online system.

Footnotes

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2011/8/1/7/79779

Contributor Information

Christopher M. Gilbert, Email: gilbertcm@upmc.edu.

Sara E. Monaco, Email: monacose@upmc.edu.

Scott T. Cooper, Email: cooperst@upmc.edu.

Walid E. Khalbuss, Email: khalbussw2@upmc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chang KJ, Albers CG, Erickson RA, Butler JA, Wuerker RB, Lin F. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of pancreatic carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:263–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrara S, Arcidiacono PG, Mezzi G, Petrone MC, Boemo C, Testoni PA. Pancreatic Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Fine Needle Aspiration: Complication rate and clinical course in a single centre. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:520–3. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.none Varadarajulu S, Wallace MB. Applications of endoscopic ultrasonography in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Control. 2004;11:15–22. doi: 10.1177/107327480401100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das A, Ngamruengphong S, Nagendra S, Chak A. Asymptomatic pancreatic cystic neoplasm: A cost-effectiveness analysis of different strategies of management. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:690–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mesa H, Stelow EB, Stanley MW, Mallery S, Lai R, Bardales RH. Diagnosis of non primary pancreatic neoplasms by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:313–8. doi: 10.1002/dc.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varghese L, Ngae MY, Wilson AP, Crowder CD, Gulbahce HE, Pambuccian SE. Diagnosis of metastatic pancreatic mesenchymal tumors by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:792–802. doi: 10.1002/dc.21104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dim DC, Nugent SL, Darwin P, Peng HQ. Metastatic merkel cell carcinoma of the pancreas mimicking primary pancreatic endocrine tumor diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology: A case report. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:223–8. doi: 10.1159/000325130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kyriazi MA, Sofoudis C, Katsouri M, Kappos T, Zafeiris C, Trihia E, et al. Acute cholangitis due to pancreatic metastasis from squamous cell lung carcinoma: A case report and review of literature. Cases J. 2009;2:9113. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-9113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khalbuss WE, Gherson J, Zaman M. Pancreatic metastasis of cardiac rhabdomyosarcoma diagnosed by fine needle aspiration.A case report. Acta Cytol. 1999;43:447–51. doi: 10.1159/000331098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva RG, Dahmoush L, Gerke H. Pancreatic metastasis of an ovarian malignant mixed Mullerian tumor identified by EUS-guided fine needle aspiration and Trucut needle biopsy. JOP. 2006;7:66–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minoguchi M, Yanagawa N, Ishikawa C, Sasajima J, Goto M, Okamoto M, et al. Pancreatic metastasis of malignant melanoma diagnosed by EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2007;104:1082–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ang TL, Ng VW, Fock KM, Teo EK, Chong CK. Diagnosis of a metastatic phyllodes tumor of the pancreas using EUS-FNA. JOP. 2007;8:35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sweeney AD, Fisher WE, Wu MF, Hilsenbeck SG, Brunicardi FC. Value of pancreatic resection for cancer metastatic to the pancreas. J Surg Res. 2010;160:268–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kassabian A, Stein J, Jabbour N, Parsa K, Skinner D, Parekh D, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the pancreas: A single institution series and review of the literature. Urology. 2000;56:211–5. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00639-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sellner F, Tykalsky N, DeSantes M, Pont J, Klimpfinger M. Solitary and multiple isolated metastasis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas: An indication for pancreatic surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:75–85. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adsay NV, Andea A, Basturk O, Kilnc N, Nassar H, Cheng JD. Secondary tumours of the pancreas: An analysis of a surgical and autopsy database and review of the literature. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:527–35. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-0987-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Machado NO, Chopra P. Pancreatic metastasis from renal carcinoma managed by Whipple resection.A case report and literature review of metastatic pattern, surgical management and outcome. JOP. 2009;10:413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moussa A, Mitry E, Hammel P, Sauvanet A, Nassif T, Palazzo L, et al. Pancreatic metastasis: A multicentric study of 22 patients. Gastroenetrol Clin Biol. 2004;28:872–6. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(04)95151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faure JP, Tuech JJ, Richer JP, Pessaux P, Arnaud JP, Carretier M. Pancreatic metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: presentation, treatment and survival. J Urol. 2001;165:20–2. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200101000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wayne M, Wang W, Bratcher J, Cumani B, Kasmin F, Cooperman A. Renal cell cancer without a renal primary. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langner C, Wegscheider BJ, Ratschek M, Schips L, Zigeuner R. Keratin immunohistochemistry in renal cell carcinoma subtypes and renal oncocytomas: A systematic analysis of 233 tumors. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:127–34. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0948-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson LD, Heffess CS. Renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas in surgical pathology material. Cancer. 2000;89:1076–88. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000901)89:5<1076::aid-cncr17>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufmann O, Dietel M, Scherberich JE, Gaedicke G, Fischer P. Immunohistochemical differentiation of metastases of renal carcinomas Versus other carcinomas with anti-gamma GT monoclonal antibody 138H11. Histopathology. 1997;31:31–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.5800813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YS, Kang YK, Kim JB, Han SA, Kim KI, Paik SR. Beta-Catenin expression and mutational analysis in renal cell carcinomas. Pathol Int. 2000;50:725–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2000.01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufmann O, Dietel M. Expression of thyroid transcription factor-1 in pulmonary and extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas and other neuroendocrine carcinomas of various primary sites. Histopathology. 2000;36:415–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long KB, Srivastava A, Hirsch MS, Hornick JL. PAX8 Expression in well-differentiated pancreatic endocrine tumors: Correlation with clinicopathologic features and comparison with gastrointestinal and pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:723–9. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181da0a20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao L, Li ZS, Jin ZD, Man XH, Zhang MH, Zhu MH. Undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells of the pancreas diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:1598–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sperti C, Pasquali C, Liessi G, Pinciroli L, Decet G, Pedrazzoli S. Pancreatic resection for metastatic tumors to the pancreas. J Surg Oncol. 2003;83:161. doi: 10.1002/jso.10262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crippa S, Angelini C, Mussi C, Bonardi C, Romano F, Sartori P, et al. Surgical treatment of metastatic tumors to the pancreas: A single center experience and review of the literature. World J Surg. 2006;30:1536–42. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0464-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]