Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to determine whether the surgical outcomes achieved with computer-aided surgical simulation (CASS) are better than those achieved with traditional methods.

Material and Methods

Twelve consecutive patients with craniomaxillofacial deformities (CMF) deformities were enrolled. Following our CASS clinical protocol, a 3D computer composite skull model for each patient was generated and reoriented to the neutral head posture. These models underwent 2 virtual surgeries: one was based on CASS (experimental group) and the other was based on traditional methods a year later (control group). Once both virtual surgeries were completed, 2 experienced oral-maxillofacial surgeons at 2 different settings evaluated both surgical outcomes. They were blinded to the planning method used on the virtual models, and each other’s evaluation results. The primary outcome was overall CMF skeletal harmony. The secondary outcomes were individual maxillary, mandibular and chin harmonies. Finally, statistical analyses were performed.

Results

Overall CMF skeletal harmony achieved with CASS was statistically significantly better than that achieved with traditional methods. In addition, the maxillary and mandibular surgical outcomes achieved with CASS method were also significantly better. Furthermore, although not included in the statistical model, the chin symmetry achieved by CASS tended to be better. Finally, a regression model was established between the mandibular symmetry and the overall CMF skeletal harmony.

Conclusion

The surgical outcomes achieved with CASS are significantly better than those achieved with traditional planning methods. In addition, CASS enables the surgeon to better correct maxillary yaw deformity, better place proximal/distal segment, and better restore mandibular symmetry. Finally, the critical step in achieving better overall CMF skeletal harmony is to restore mandibular symmetry.

Introduction

Craniomaxillofacial (CMF) surgery involves the correction of congenital and acquired conditions of the head and face. Each year throughout the world, many patients require surgical correction for these deformities.1–7 The success of CMF surgery depends not only on the technical aspects of the operation, but to a larger extent on the formulation of a precise surgical plan.8–15 Unfortunately, the traditional planning methods, i.e. prediction tracings and surgical simulation on stone dental models, have remained mostly unchanged over the last 50 years.9, 10, 12, 16 They present significant limitations and are often inadequate for the treatment of patients with complex CMF deformities12–14, 16, 17. Each one of these limitations can result in a poor surgical outcome.17 In isolation, these problems may be minor, but when added together they can be significant.

In order to rectify these problems, surgeons have begun to use 3D computeraided surgical simulation (CASS) to plan complex CMF surgery.17 With CASS, the surgeon is able to perform “virtual surgeries” and create a 3D prediction of the surgical outcomes. To date, many CMF procedures have been planned utilizing the CASS system, including maxillofacial surgery12, 13, craniofacial surgery18, 19, trauma19, 20, distraction osteogenesis16, reconstruction after tumor ablation19, 21, and TMJ reconstruction22. The authors have documented the clinical feasibility10, accuracy23 and cost-effectiveness24 of the CASS system developed in our surgical planning laboratory. However, the “better surgical outcomes” achieved with the CASS method are based only on our clinical observation. It has not been quantitatively documented whether CASS has produced a better surgical outcome. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to determine whether the surgical outcomes achieved with CASS are better than those achieved with traditional methods.

Patients and Methods

A total of 12 consecutive patients with CMF deformities seen between July 2006 and June 2008 were enrolled in the study. Inclusion criteria were: 1) patients who were scheduled to undergo double-jaw orthognathic surgery to treat dentofacial deformities or hemifacial microsomia; 2) patients who were scheduled to undergo a CT scan as a part of their treatment; and 3) patients who agreed to use the CASS protocol for their treatment planning. The study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) and informed consent was obtained prior to the patient’s enrollment.

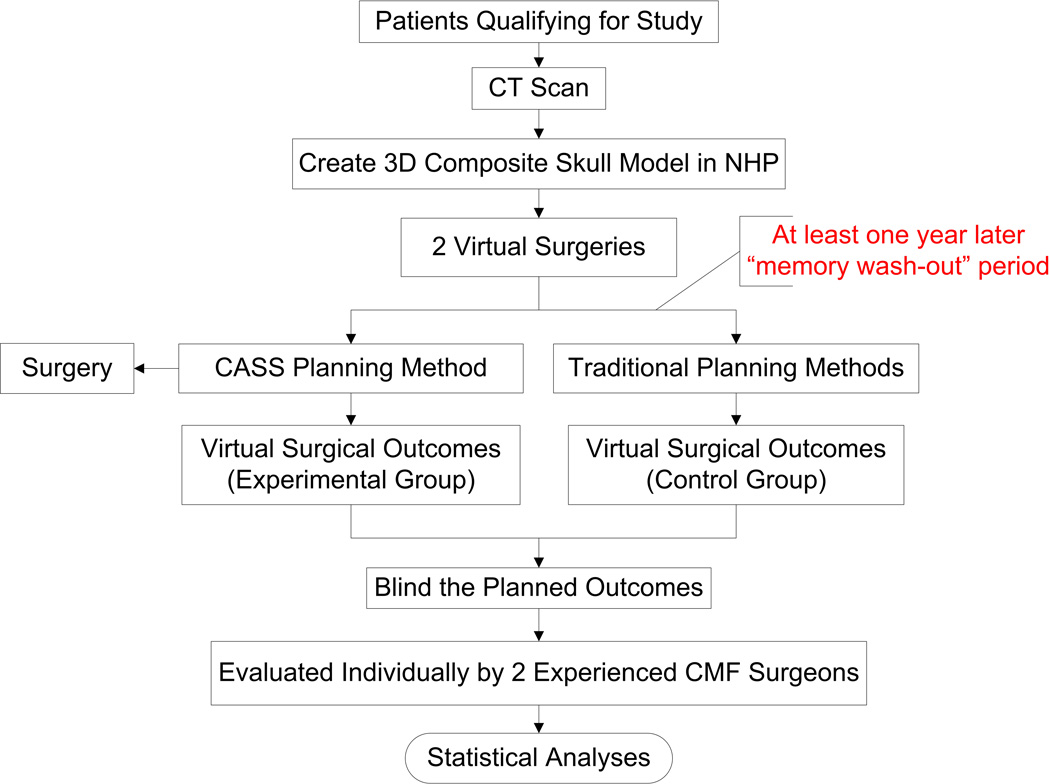

Following our CASS clinical protocol17, a 3D computer composite skull model for each patient was generated and reoriented to the neutral head posture.17 These models underwent 2 virtual surgeries (Fig. 1): one was planned based on CASS10, 17 (experimental group) and the other was planned based on traditional methods8, 25, 26 (control group). An experienced surgeon (J.G.) planned the first surgery using CASS (Figs. 2–6), which was also used in the patient’s actual treatment. At least one year later, the same surgeon planned the second virtual surgery using traditional planning methods. We felt that 1-year “wash-out-memory” interval would prevent undue influence from the previous CASS plan. Two-dimensional cephalometric analysis and prediction tracing were completed using a prediction tracing software (CASSOS, SoftEnable Corp, Hong Kong, China). Stone dental model surgery was followed. These models were mounted onto an articulator using facebow transfer and bite registration during the patient’s presurgical clinical examination visit.

Figure 1.

Study design

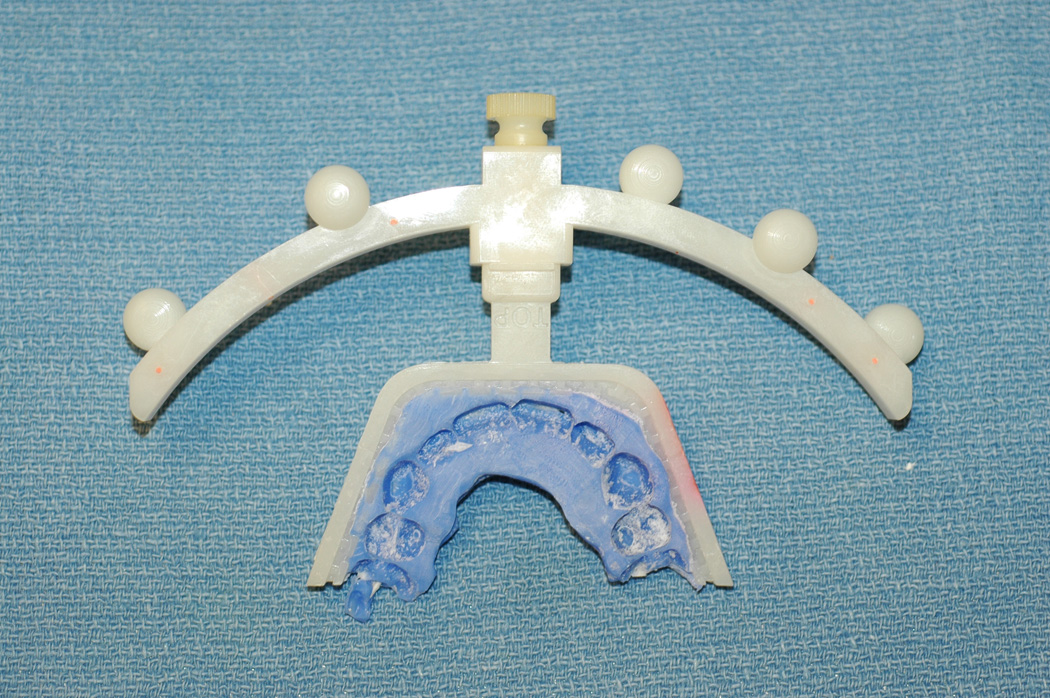

Figure 2.

- An individualized bite-jig was first created and attached with a facebow assembly (Medical Modeling Inc, Golden, CO). The individualized bite-jig was a bite fork (Medical Modeling Inc, Golden, CO) holding a patient’s bite registration taken by a dimensionally-stable, rigid, bite registration material, e.g. LuxaBite (Chemisch-Pharmazeutische Fabrik GmbH, Hamburg, Germany).

- The patient was undergone a computed tomography scan with the bite-jig and facebow in place.

- Three separate but correlated computer models are reconstructed: a midface model, a mandibular model and a fiducial-marker model.

- The same bite-jig and facebow was placed between the upper and lower plaster dental models for a high-resolution surface laser scan (Medical Modeling Inc, Golden, CO).

- Three separate but correlated computer models were reconstructed: an upper digital dental model, a lower digital dental model, and a fiducial-marker model.

- By aligning the fiducial markers, the digital dental models were incorporated into the 3D CT skull model. The computerized composite skull model was thus created. It simultaneously displayed an accurate rendition of both the bony structures and the teeth.

Figure 6.

- After the surgical simulation was finalized, the computerized plan was transferred to the patient at the time of the surgery using surgical dental splints and templates. The digital surgical splints and templates were fabricated in the computer using CAD technique (a and b). The physical surgical splints and templates were fabricated using a rapid prototyping machine (c and d) and used at the time of the surgery (e and f).

Once both virtual surgeries were completed, two experienced oral-maxillofacial surgeons at two different settings evaluated the outcomes of both virtual surgeries. Neither examiner was involved in the presurgical planning process or the virtual surgeries for these patients. They were also blinded to the planning method used on the virtual models, and each other’s evaluation results.

The outcomes were evaluated as follows. The primary outcome measure was overall CMF skeletal harmony. The secondary outcome measures were individual maxillary, mandibular and chin harmonies. The maxillary measurements included maxillary midline correction, cant correction, yaw correction, and occlusal plane inclination to Frankfurt horizontal (FH). The mandibular measurements included mandibular symmetry and proximal/distal segment placement. The chin measurements included the chin position and projection in all 3 dimensions.

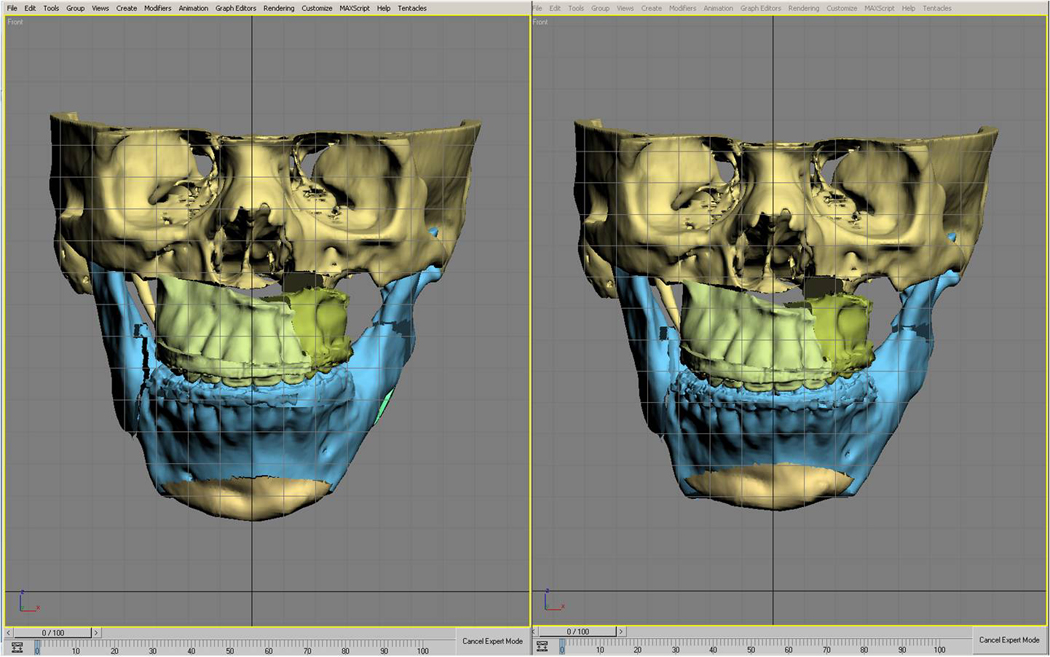

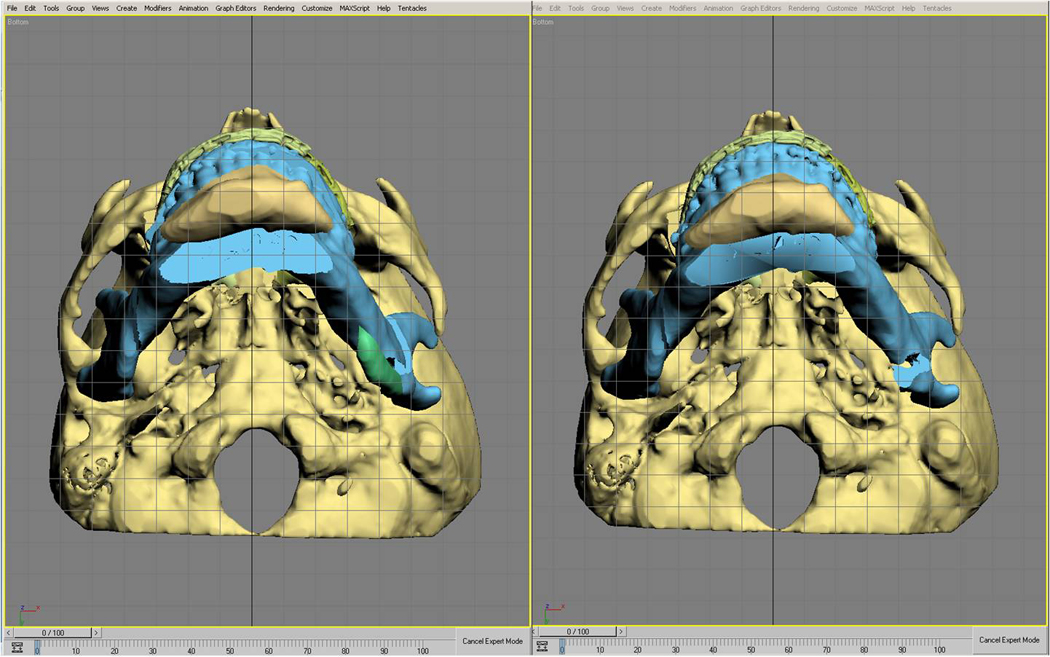

During the evaluation, two 3D models of the same patient were placed side by side on a 24” high-resolution widescreen (Fig. 7). The examiners evaluated both of these 3D models using a visual analog scale (VAS, ranged 0–10, a score of “10” entailed the best outcome, while a score of “0” entailed the worst). Prior to the formal evaluation, a training session was held for each examiner on the use of the VAS scoring system in evaluating the surgical outcomes.

Figure 7.

- Frontal View

- Lateral View

- Bottom View

After the evaluation was completed, the surgical planning methods were unblinded. The VAS scores determined by the 2 examiners were paired. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) using a two-way mixed model for absolute agreement was performed to detect the consistency of the measurements between the two examiners. The result showed that ICC was 0.83 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.77, 0.88, p<0.01], indicating that the measurements between the 2 examiners were highly consistent. The VAS scores determined by the 2 examiners were then averaged and paired for the two planning methods.

The data was screened and its distribution was normally shaped. Paired t-test (for the primary outcome measure) and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures (for the secondary outcome measures) were used to detect whether there was a statistically significant difference between the 2 planning methods. In ANOVA for repeated measures, the response variable was the VAS score, and the within factors were the 2 methods and 6 measurements. We did not include the outcome measures of the genioplasty because only 3 patients underwent this procedure. If there was a statistically significant difference, the within factor contrast would be computed. Finally, a regression model was computed to detect which measurement would most likely contribute to the overall CMF skeletal harmony. SPSS (version 13.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) statistical software package was used for the computation.

Results

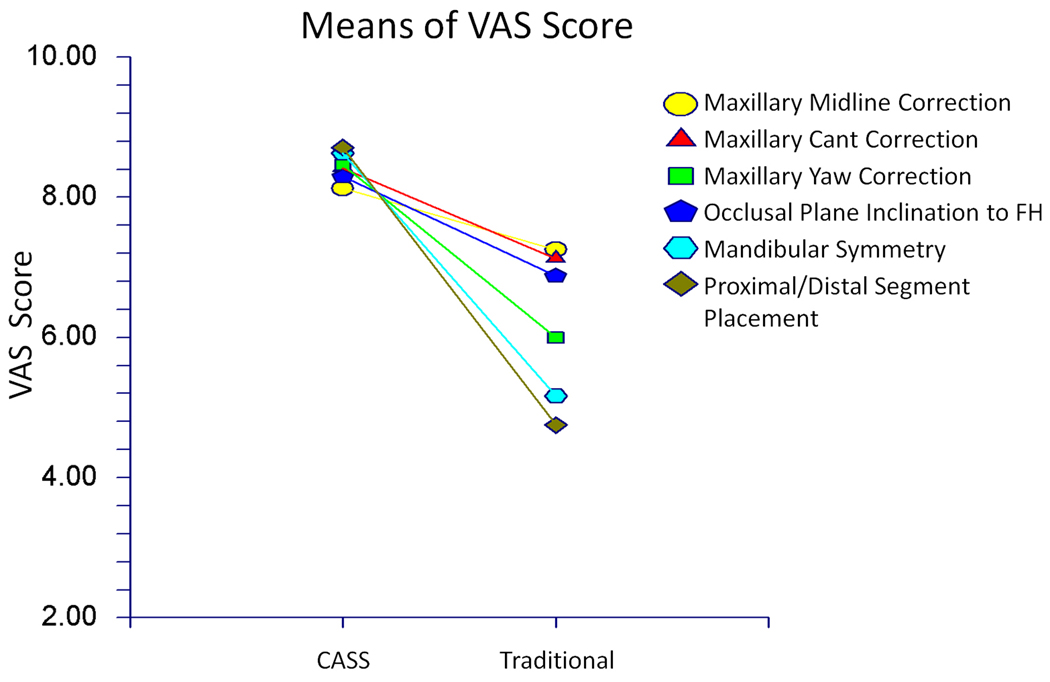

The mean differences of the VAS scores (CASS - traditional) and their 95% CI are shown in Table 1. Overall CMF skeletal harmony achieved with CASS was significantly better than that achieved with traditional methods (p<0.01, Fig. 8). In addition, the maxillary and mandibular surgical outcomes achieved with CASS method were significantly better (p<0.01). The results of the within factor contrast computation showed that each secondary outcome achieved with CASS was also significantly better (Table 1, Fig. 9). Finally, although we could not include the outcome measures of genioplasty in our statistical model, the chin symmetry achieved by CASS tended to be better than that achieved by the traditional planning methods (median difference of VAS score: 3.0 in VAS score from lateral view, 3.0 from bottom view, and 3.5 from frontal view, respectively).

Table 1.

The mean differences of the VAS scores (CASS - traditional) and their 95% confidence interval.

| Measurements | Mean Difference | SD | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall CMF Skeletal Harmony | 3.7 | 1.9 | (2.5, 4.9) |

| Maxilla | |||

| Midline Correction | 0.9 | 0.9 | (0.2, 1.5) |

| Cant Correction | 1.3 | 0.8 | (0.6, 2.0) |

| Yaw Correction | 2.5 | 1.1 | (1.8, 3.1) |

| Occlusal Plane Inclination to FH | 1.4 | 0.7 | (0.7, 2.1) |

| Mandible | |||

| Symmetry | 3.5 | 1.5 | (2.8, 4.1) |

| Proximal/Distal Segment Placement | 4.0 | 1.2 | (3.3, 4.6) |

| Chin | |||

| Lateral View | 3.0 | N/A | (1.5, 3.0)* |

| Bottom View | 3.0 | N/A | (1.0, 4.0)* |

| Frontal View | 3.5 | N/A | (1.5, 3.5)* |

Using range instead of 95% CI

Figure 8.

Comparison of Overall CMF Skeletal Harmony achieved with CASS and traditional methods

Figure 9.

Comparisons of the secondary outcome measures achieved with CASS and traditional methods

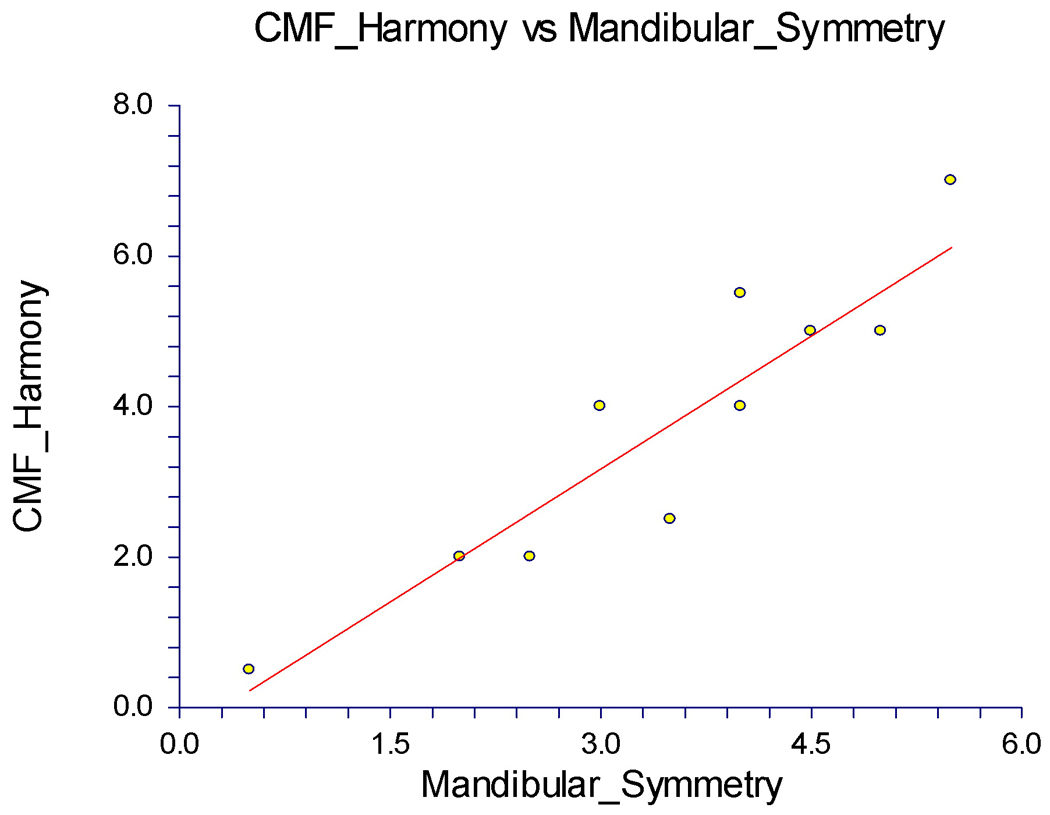

The regressions between overall CMF skeletal harmony and the individual secondary outcome measures are shown in Table 2. Three measures were statistically correlated to overall CMF skeletal harmony. They included maxillary yaw correction, proximal/distal segment placement, and mandibular symmetry. Because maxillary yaw correction and proximal/distal segment placement directly contributed to mandibular symmetry, the first two were the confounding factors for mandibular symmetry and thus were eliminated from the regression equation. Finally, the regression model was computed as follows (Fig. 10):

Table 2.

Regressions between overall CMF skeleton harmony and the individual secondary outcome measures for maxilla and mandible

| Overall CMF Skeletal Harmony |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | Probability | ||

| Maxilla | R2 | Coefficient | Level |

| Midline Correction | 0.15 | 0.85 | 0.22 |

| Cant Correction | 0.14 | 0.89 | 0.24 |

| Yaw Correction | 0.54 | 1.30 | < 0.01 |

| Occlusal Plane Inclination to FH | 0.42 | 1.75 | 0.06 |

| Mandible | |||

| Symmetry | 0.86 | 1.18 | < 0.01 |

| Proximal/Distal Segment Placement |

0.65 | 1.25 | < 0.01 |

Figure 10.

Linear regression between Overall CMF Skeletal Harmony and Mandibular Symmetry

The y-intercept, the estimated value of overall CMF skeletal symmetry when mandibular symmetry was zero, was -0.36 with a standard error of 0.56. The slope, the estimated change in overall CMF skeletal symmetry per unit change in the mandibular symmetry, was 1.19 with a standard error of 0.15. The value of R2, the proportion of the variation in overall CMF skeletal symmetry that could be accounted for by variation in mandibular symmetry, was 0.86. The correlation between overall CMF skeletal symmetry and mandibular symmetry was 0.93 (P<0.01).

Discussion

Our study has confirmed that the surgical outcomes achieved with CASS are significantly better than those achieved with traditional planning methods. In addition, our study has also confirmed that CASS enables the surgeon to better correct maxillary yaw deformity, better place proximal/distal segment, and better restore mandibular symmetry. Finally, our study has discovered that the critical step in achieving better overall CMF skeletal harmony is to restore mandibular symmetry.

During the evaluation, both examiners noted qualitatively that the outcome differences between the 2 planning methods were greater in those patients with more severe or asymmetrical deformities. The outcome differences were less pronounced in those patients with mild and symmetrical deformities. This observation was confirmed after we ranked each patient’s outcome difference from the least to the highest. The 4 patients with the smallest outcome differences had symmetrical dentofacial deformities. In contrast, in the 4 patients with the largest outcome differences, 3 had hemifacial microsomia and 1 had severe maxillary hypoplasia and mandibular hyperplasia. In addition, both examiners noted that the outcome difference in the mandibular surgery was more significant than in the maxillary surgery. This observation was also confirmed after we ranked the mean difference of the secondary outcome measures (Table 1) from the least to the highest as follows: maxillary midline correction, maxillary cant correction, occlusal plane inclination to FH, maxillary yaw correction, mandibular symmetry correction, and proximal/distal segment placement. This can be explained by the concept of a radius and an arc in which a longer radius produces a larger arc even with the same rotational angle. Assume that the cranial base is the center of rotation. The maxilla has a shorter distance (radius) to the cranial base while the mandible has a longer one. A small improvement in the maxilla will result in a larger improvement in mandibular symmetry, thus greatly improving overall CMF skeletal harmony.

The placement of the proximal and the distal segments plays an important role in mandibular symmetry. In this study, the largest mean difference in VAS score (4.0) between the 2 planning methods was in the proximal/distal segment placement. There is no way of planning the proximal/distal segment placement using the traditional planning methods. However, using CASS, the surgeon is able to clearly see the computer models of both the proximal and the distal segments and their simulated placement. If the proximal segment is kicked out too much by the distal segment, it will distort the mandibular symmetry. In this case, the surgeon need to revisit the surgical plan by changing the mandibular surgery from sagittal split osteotomy to vertical sigmoid osteotomy, or correct less maxillary yaw deformity in order to decrease the rotation of the distal segment in yaw.

The correction of maxillary midline deviation plays an important role in CMF skeletal harmony. The midline correction is always based on clinical judgment and CASS only serves as a verification tool to determine if the clinical and the computer measurements are in agreement.17 This explains why the mean difference in midline deviation between the 2 methods was minimal (0.9 in VAS score). However, CASS provides a surgeon the ability to fine-tune the correction of the midline correction in sub-millimeters, which cannot be achieved with traditional methods. Therefore, the maxillary midline correction achieved with CASS is still significantly better than that achieved with the traditional planning methods (15% better chance, R2 in Table 2).

We initially included the maxillary vertical dimension as a part of the secondary outcome measures. However, during the evaluation, both examiners found it was impossible to evaluate the vertical dimension of the maxilla without knowing the clinical measurements (i.e. incisor show) and the soft tissue changes postoperatively. Therefore, this item was excluded from our evaluation chart.

We recognize that the ideal study design to evaluate surgical outcomes with different planning methods is a randomized controlled trial (RCT). However, since we believe that the CASS planning method is superior to the traditional planning methods, we felt that it was not in the patients’ best interest to randomize them to a control group using the traditional planning methods. In addition, the deformity of each patient is different due to the complex nature of CMF deformities. We found that it was technically difficult to randomize patients with different deformities in order to compare their surgical outcomes. Therefore, we have designed this study so that a single patient can undergo 2 different virtual procedures based on 2 different surgical plans. This results in 2 different surgical outcomes: one with CASS, the other with the traditional planning methods.

Finally, potential bias may still exist in the design of this study. Although we set one-year “wash-out memory” interval to prevent undue influence of the surgical plan from CASS, the surgeon’s bias may still exist during the traditional planning process. This bias tends to positively influence the surgical outcomes achieved by the traditional planning methods. However, the surgical outcome achieved with CASS was still significantly better.

Figure 3.

- A digital orientation sensor was attached to the same facebow. With the patient in the NHP, the pitch, roll and yaw of the face were recorded.

- The recorded pitch, roll and yaw. They were then used to reorient the composite skull model.

- In the computer, a digital replica (computer-aided design [CAD] model) of the digital orientation sensor was registered to the composite skull model via the fiducial markers and the 2 objects are attached to each other.

- The recorded pitch, roll and yaw were applied to the center of the digital orientation sensor replica reorienting the composite skull model to the NHP.

- After the composite skull model was oriented to the NHP, the digital orientation sensor is marked hidden.

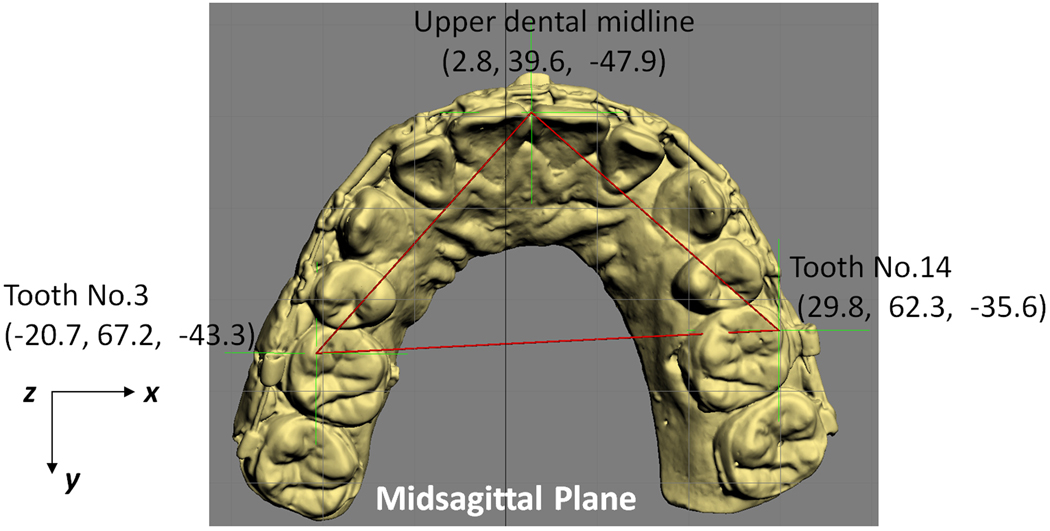

Figure 4.

- Two- and 3-dimensional cephalometric analyses and anthropometric measurements were performed to quantify the deformity. Illustrated is a symmetry analysis of a maxilla.

Figure 5.

- Any type of osteotomy, i.e., Le Fort I, sagittal split, inverted-L, genioplasty, etc, could be simulated in the computer. After the bones were osteotomized, they were moved and rotated to the desired position.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by NIH/NIDCR grants 1R41DE016171-01 and 2R42DE016171-02A1, Methodist Hospital Research Institute Scholar Award, and UCRC (UT-Houston Medical School) grant M01 RR002558 (NIH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This manuscript was submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Master of Science at The University of Texas Houston Health Science Center Dental Branch (L.S.).

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. National Hospital Discharge Survey: Annual Summary with Detailed Diagnosis and Procedure Data. Vital and Health Statistics series 13 number 151. DHHS publication No.(PHS)2001-1722. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institutes of Health. Management of temporomandibular disorders. National Institutes of Health Technology Assessment Conference Statement. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:1595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Center for Health Statistics. Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, (NHANES III, 1988–1994) Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Proffit WR, Fields HW, Jr, Moray LJ. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in the United States: estimates from the NHANES III survey. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998;13:97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorlin RJ, Cohen MM, Hennekam RCM, editors. Syndromes of the head and neck. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.WISQARS. Overall all injury causes nonfatal injuries and rates per 100,000 (2001–2002, United States) Altanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lew TA, Walker JA, Wenke JC, et al. Characterization of craniomaxillofacial battle injuries sustained by United States service members in the current conflicts of Iraq and Afghanistan. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:3. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell WH, editor. Modern practice in orthognathic and reconstructive surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell WH, Guerrero CA. Distraction Osteogenesis of the Facial Skeleton. 1st ed. BC Decker, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gateno J, Xia JJ, Teichgraeber JF, et al. Clinical feasibility of computer-aided surgical simulation (CASS) in the treatment of complex cranio-maxillofacial deformities. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:728. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santler G. 3-D COSMOS: a new 3-D model based computerised operation simulation and navigation system. J Maxillofac Surg. 2000;28:287. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2000.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swennen GR, Barth EL, Eulzer C, et al. The use of a new 3D splint and double CT scan procedure to obtain an accurate anatomic virtual augmented model of the skull. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:146. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swennen GR, Mommaerts MY, Abeloos J, et al. The use of a wax bite wafer and a double computed tomography scan procedure to obtain a three-dimensional augmented virtual skull model. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:533. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e31805343df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Troulis MJ, Everett P, Seldin EB, et al. Development of a three-dimensional treatment planning system based on computed tomographic data. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;31:349. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia J, Ip HH, Samman N, et al. Computer-assisted three-dimensional surgical planning and simulation: 3D virtual osteotomy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;29:11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia JJ, Gateno J, Teichgraeber JF. Three-dimensional computer-aided surgical simulation for maxillofacial surgery. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005;13:25. doi: 10.1016/j.cxom.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia JJ, Gateno J, Teichgraeber JF. New clinical protocol to evaluate craniomaxillofacial deformity and plan surgical correction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2093. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gateno J, Teichgraeber JF, Xia JJ. Three-dimensional surgical planning for maxillary and midface distraction osteogenesis. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:833. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell RB, Markiewicz MR. Computer-assisted planning, stereolithographic modeling, and intraoperative navigation for complex orbital reconstruction: a descriptive study in a preliminary cohort. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2559. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia JJ, Gateno J, Teichgraeber JF. A new paradigm for complex midface reconstruction: a reversed approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:693. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirsch DL, Garfein ES, Christensen AM, et al. Use of computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing to produce orthognathically ideal surgical outcomes: a paradigm shift in head and neck reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2115. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malis DD, Xia JJ, Gateno J, et al. New protocol for 1-stage treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis using surgical navigation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1843. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia JJ, Gateno J, Teichgraeber JF, et al. Accuracy of the computer-aided surgical simulation (CASS) system in the treatment of patients with complex craniomaxillofacial deformity: A pilot study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:248. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia JJ, Phillips CV, Gateno J, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis for computer-aided surgical simulation in complex cranio-maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1780. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bell WH, editor. Surgical correction of dentofacial deformities. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epker BN, Stella JP, Fish LC. Dentofacial deformities. Mosby St. Louis; 1995. [Google Scholar]