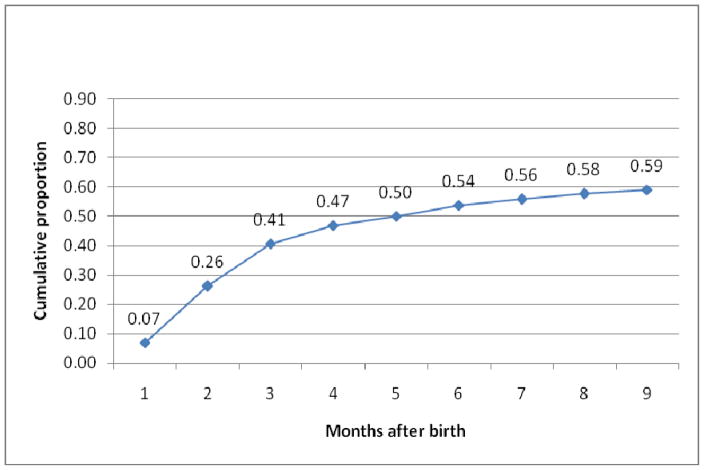

One of the most striking changes in American society in recent decades has been the dramatic rise in the labor force participation of women with children and, in particular, mothers of infants. In 1968, for instance, just 21 percent of women with a child under the age of one were in the labor force.4 By 1986, this figure exceeded 50 percent and, although the increase has slowed since that time and appears to have stabilized since 2000, over half of mothers of infants have participated in the labor force in every year since.5 There are important distinctions, however, between labor force participation, employment, and actually being at work. Current data indicate that a majority of mothers of infants are both in the labor force and at work by the end of the first year post-birth (see Figure 1 below).6 Thus, a mother working in the first year of life has become normative in the U.S., in sharp contrast to the situation in the 1960s.

Fig. 1.

Post-birth employment rates of US women giving birth in 2001

Yet, the statistic that over half of mothers are at work within the first year after their child’s birth masks considerable variation in the timing of post-birth employment. This article focuses on that variation. In particular, we examine how mothers’ employment post-birth varies by their race/ethnicity, family structure, education level, age, and prior birth history. We also consider how mothers’ employment varies by their previous attachment to the labor force, specifically, whether they were employed immediately prior to the birth.

We address these questions using data from a new national birth cohort – the Early Child Longitudinal Study – Birth Cohort (ECLS-B). The ECLS-B used Vital Statistics records to select a sample of over 10 000 children born in 2001. The sample is designed to be representative of all US births in that calendar year, and also includes oversamples of Asian and Pacific Islander children, American Indian and Alaska Native children, Chinese children, twins, and low and very low birth weight children.

Baseline parent interviews and child assessments were done when the child was approximately nine months old (there are also interviews at 24 months, pre-school entry, and kindergarten, which we do not use here). The nine-month (baseline) ECLS-B interview consists of a computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) administered to the parent respondent (the biological mother in 99% of the cases), as well as direct assessments of the child’s development, caregiver-child interaction patterns, a self-administered questionnaire for the resident father or male guardian, as well as the non-resident father if permission was granted by the mother and he was located.1

The nine-month personal interview provides rich information on current maternal and paternal employment characteristics, including hours of work, earnings, occupation, and employer benefits (for those in work only). However, information on employment in the immediate pre- and post-birth periods is more limited. Mothers were asked if they had worked at all in the 12 months prior to the birth and, if so, for how many months they had worked and their usual weekly hours of work in that job. With regard to the post-birth period, mothers were asked about the number of weeks of paid and unpaid leave they had taken, and about the age of the child in months when they first began to work.

We focus on the latter of these two sources of post-birth employment information in this article for several reasons. Firstly, the maternity leave data is only relevant for women who were employed at the time of the birth. Yet of those mothers who had begun work by 9 months (59% of all mothers), 11% had not worked at all in the year prior to the birth, and a further 14% had separated from their employer prior to the birth. Even amongst mothers who were employed at the time of the birth, length of maternity leave may not coincide with length of time away from work because some mothers may quit their jobs after taking official leave (information on the identity of the employer is not available). Data on theactual dates at which mothers start work are therefore defined for the entire sample, and not just those who returned to work with their pre-birth employer. Our aim here is to compare the time spent at home with a newborn for a nationally representative group of mothers, and hence we make no distinction between mothers who are employed but on leave, and those who are not currently employed.

The aim of this article is to describethe variation in the timing of mothers’ employment post-birth as a function of several key characteristics identified as important by theory and prior research2. We also estimate multivariate models to shed light on which of these are most influential. Table 1 shows the composition of the sample in terms of these selected demographic characteristics3.

Table 1.

Probit models of the timing of return to work following a birth

| Marginal effect on probability of return by: | ||

|---|---|---|

| End of Month 2 | End of Month 9 | |

| Black non-Hispanic | −0.06 (0.02)*** | 0.04 (0.02)* |

| Hispanic | −0.02 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.02) |

| Asian | 0.00 (0.02) | −0.08 (0.02)*** |

| Cohabiting | 0.06 (0.02)*** | 0.14 (0.02)*** |

| Single mother | 0.08 (0.02)*** | 0.11 (0.02)*** |

| Less than high school | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.08 (0.02)*** |

| High school | 0.03 (0.02)** | −0.03 (0.02) |

| Bachelor’s degree | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.02 (0.02) |

| More than bachelor’s degree | −0.06 (0.02)*** | 0.01 (0.03) |

| Age less than 20 | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.03)** |

| Age 20–24 | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.04 (0.02)* |

| Age 30–34 | −0.05 (0.01)*** | −0.01 (0.02) |

| Age 35+ | −0.06 (0.02)*** | −0.05 (0.02)** |

| Second-born | 0.04 (0.01)*** | 0.00 (0.02) |

| Third-born or more | 0.05 (0.02)*** | −0.07 (0.02)*** |

| Employed at birth | 0.39 (0.01)*** | 0.58 (0.01)*** |

| Mean of outcome | 0.26 | 0.59 |

Omitted categories are: white non-Hispanic, married, some college, age 25–29, first-born. Estimated marginal effects in each column are derived from a separate probit model (N=10,465). Standard errors are in parentheses.

indicate significance at the 1, 5 and 10% levels respectively.

All estimates weighted to adjust for complex survey design.

A number of potentially interesting characteristics are excluded from the analysis. Firstly, we are unable to address the role of factors such as employer characteristics and household income. The nature of these factors prior to the pregnancy may be an important influence on family decisions, but they are not observed in our data. Although information of this kind is available at nine months, these data suffer from the problem that employment information is missing for those who have not started work, and also that they reflect the outcomes of the decisions in which we are interested, rather than the influences upon those decisions. For example, since maternal occupation is only defined for those in work at nine months, we cannot compare the employed and non-employed proportions for a given occupation. Further, mothers may change or downgrade occupations following a birth, a decision made jointly with when and how much to work.

We have also restricted our focus to maternal characteristics, despite the fact that rich information is available on the current employment and personal characteristics of resident fathers at nine months. This is because maternal and paternal characteristics are often strongly positively related within families, and so the inclusion of both in analysis can be confusing to interpretation. Paternal employment decisions are likely to be made jointly with those of the mother, and so are subject to the problem described above of being outcomes rather than influences in the data recorded at nine months. And since one-fifth of the children born in this cohort have no resident father, a focus on maternal characteristics alone allows us to make comparative statements that apply to the entire population, rather than to a subset.

We address these questions using data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey –Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), a new nationally representative sample of over 10,000 U.S. children born in 2001.4 The ECLS-B gathered information on child and family characteristics from parents approximately nine months after the child’s birth (see descriptive statistics in Appendix Table A.1), as well as information on whether the mother had worked since the birth and, if so, when she first went to work. This article describes the variation in the timing of mothers’ employment post-birth as a function of several key characteristics identified as important by theory and prior research.5 We also estimate multivariate models to shed light on which of these are most influential.

The timing of mothers’ employment

Figure 1 shows the proportion of mothers at work over the first nine months post-birth. Although relatively few mothers (only 7 percent) are working one month after the birth, 26 percent do so after two months and 41 percent by three months. A decreasing proportion of women return in subsequent months but by nine months post-birth, just under 60 percent of all mothers are working.

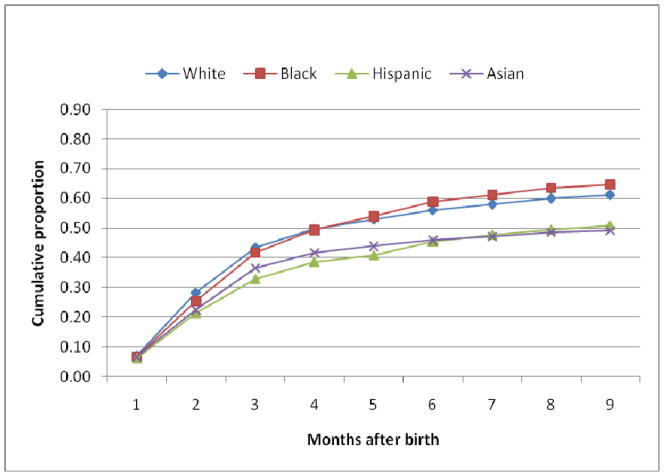

We next examine how the timing of the return to work varies across different groups of mothers. Figure 2 displays the results for subsamples stratified by race/ethnicity. Although employment timing is similar across groups in the first two months, gaps open by the third month and widen thereafter. Black and white mothers have the highest employment rates at nine months, 65 and 61 percent, compared to around 50 percent of Hispanic and Asian women. (Detailed data are provided in Appendix Table A2). The high (low) employment rates of black and white (Hispanic and Asian) mothers are consistent with racial/ethnic differences in employment for women as a whole.6 Such disparities may reflect cultural norms and attitudes, or differences in other characteristics that are correlated with race/ethnicity. We will explore the role of the latter in our multivariate analysis below.

Fig. 2.

Post-birth employment rates, by race/ethnicity

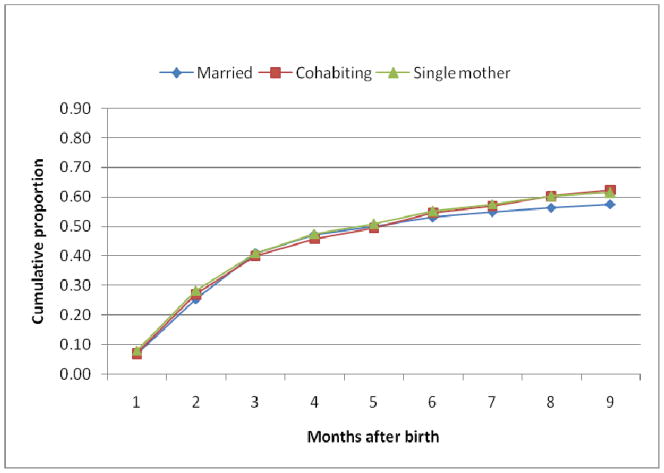

A second key characteristic is family structure. Single mothers may feel more financial pressure to work than their married counterparts, since they cannot rely on a husband’s earnings. Women cohabiting with a partner may also have more incentive to work, if they are less certain of support from their non-marital partners. Nevertheless, the descriptive analysis, summarized in Figure 3, reveals few differences until the later months, when a slight gap opens up, with cohabiting and single mothers somewhat more likely to be employed than married mothers by nine months post-birth (see Appendix Table A3 for details).

Fig. 3.

Post-birth employment rates, by family type

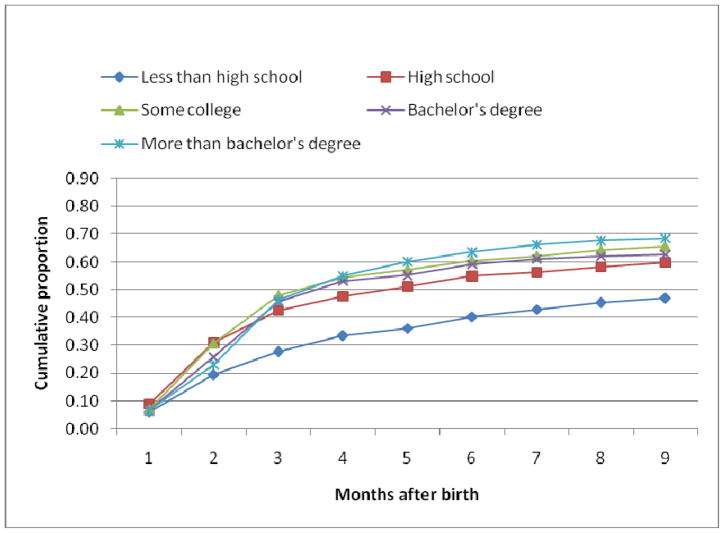

Education matters too. On the one hand, highly educated women are likely to have invested more in preparation for careers and earn a higher reward in the labor market, so we expect them to have higher rates of post-birth employment. On the other hand, these mothers are also most likely to be eligible for maternity leave, which may delay their return to work.7 Figure 4 indicates that post-birth employment rates do generally increase with education, with sharply lower rates observed for the least educated (mothers who have not completed high school). By nine months post-birth, 68 percent of those with more than a bachelor’s degree are working, versus 60 percent of those with a high school degree and only 47 percent of those with less than a high school diploma (see detailed data in Appendix Table A.4). However, in the first two months post-birth, mothers with more than a bachelor’s degree are less likely than high school graduates to be at work, probably reflecting differences in the access to or take-up of maternity leave.

Fig. 4.

Post-birth employment rates, by maternal education

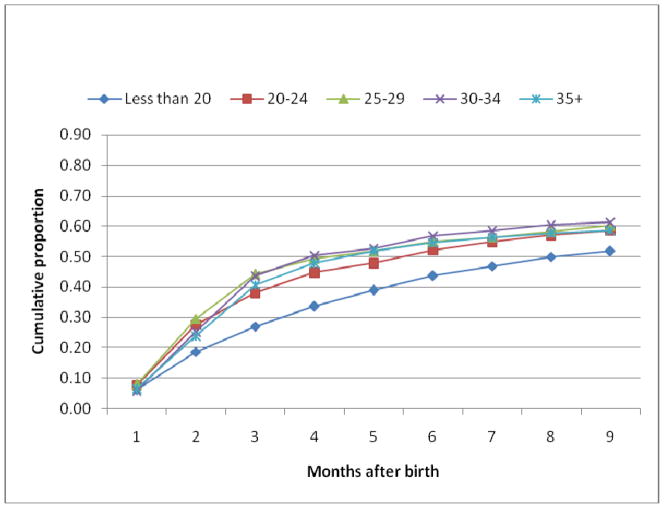

The expected association between mothers’ age, the fourth characteristic we examine, and employment timing is not clear. Older mothers may have more financial resources and so be able to stay out of the labor force for a longer period of time, and they are also more likely to have access to maternity leave.8 However, older mothers also tend to be highly educated, and so have an incentive to return more quickly, as just discussed. Figure 5 suggests few differences in employment rates by maternal age, except that mothers under the age of 20 go to work more slowly (Appendix Table A.5 provides details).

Fig. 5.

Post-birth employment rates, by maternal age at birth

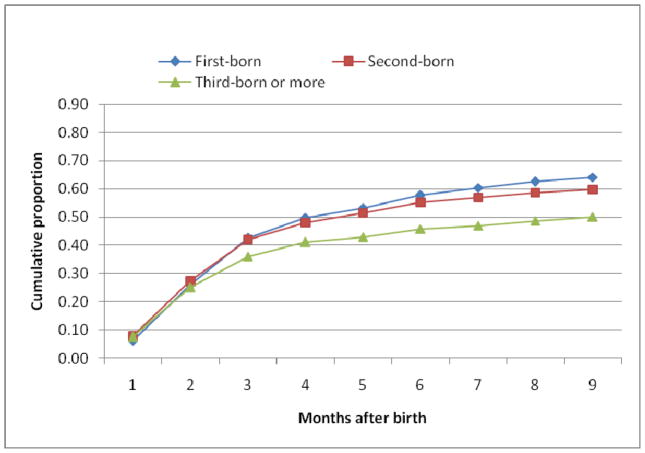

Birth order may also make a difference. In particular, women with a large number of children may be particularly likely to stay at home. The data in Figure 6 confirm this. Rates of employment following first and second births are notably higher than after third and later births. By nine months post-birth, 64 and 60 percent of the first and second groups are working versus 50 percent of the third (details are in Appendix Table A.6).

Fig. 6.

Post-birth employment rates, by child birth order

Many of the aforementioned factors are likely to affect women’s employment before as well as after the birth. Prior research has consistently found that pre-birth employment is the single strongest predictor of post-birth employment.9 This is true in the ECLS-B data as well. As shown in Figure 7, fully two-thirds of women who were employed pre-birth are back at work by three months, and nearly all (87 percent) by nine months. In contrast, only 19 percent of women who were not employed at the time of the birth are working by three months and 41 percent by nine months.

Fig. 7.

Post-birth employment rates, by employment status at birth

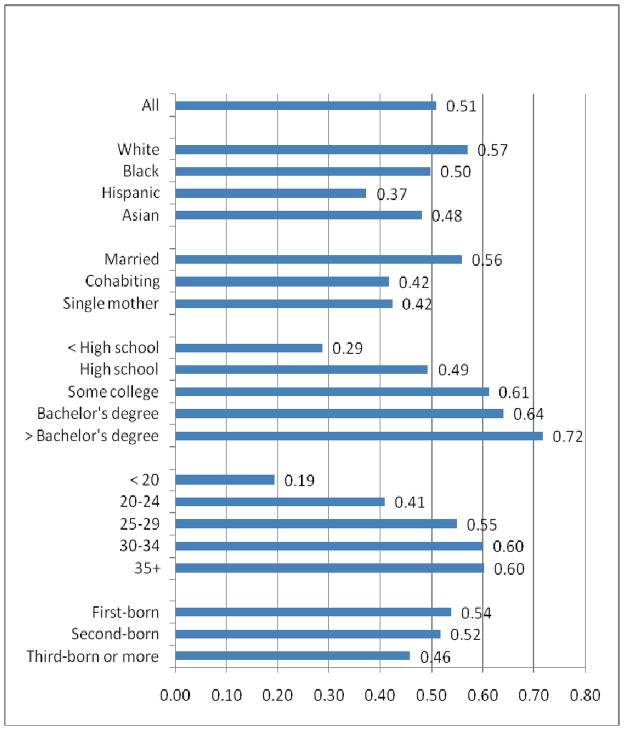

The strong link between employment before and after giving birth raises the question of the extent to which the differences summarized in Figures 1–6 may be due to differences in employment rates pre-birth. Specifically, do the groups less likely to be employed post-birth also have low pre-birth employment probabilities? As shown in Figure 8, for the most part, the answer is yes. For instance, Hispanic, Asian, cohabiting, and single mothers all have relatively low rates of pre-birth employment, and there are also sharp differences by maternal education and age. Differences in pre-birth employment by number of children are also evident but these are fairly small.

Fig. 8.

Proportion of women in employment at time of giving birth, by demographic characteristics

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with the timing of mothers’ employment

To shed light on how various factors are related with the timing of mothers’ employment post-birth, we estimated two multivariate regression models for our ECLS-B sample, controlling for all of the factors considered above -- race/ethnicity, family structure, education, age, birth history, and pre-birth employment status. The dependent variable in the first specification indicated whether the mother was employed by two months post-birth, while that of the second was employment at nine months after the birth. We estimated both models using probit regressions, because the outcome variable – whether a woman was employed by a given time point – is dichotomous (taking the value of one for women who were working and zero for those who were not). From the probit estimates we calculated marginal effects of changes in particular variables. Specifically, we indicate the percentage point change in employment associated with being in the specific category rather than another. The probit standard errors were used to determine whether the estimates were significantly significant.

Table 1 summarizes results of the multivariate estimates, with the outcome in column 1 (2) being whether the mother worked at two (nine) months. The probit estimates indicate that black mothers are 4 percentage points more likely than white women to be employed by nine months, confirming the pattern shown in Figure 2. However, black women are 6 percentage points less likely to be employed at two months, indicating a slower initial return to work. This may occur because black women are more likely (than white women) to have maternity leave rights covering the first months after giving birth.10

Figure 2 also revealed a lower likelihood of employment for Hispanic and Asian women. With the additional controls, however, Hispanic women are no less likely than their white counterparts to be working at either two or nine months. Conversely, Asian mothers continue to have an 8 percentage point lower employment rate at nine months (but with no difference at two months).

Figure 3 suggested that cohabiting and single mothers were slightly more likely to be working at nine months than married mothers. After controlling for other factors, these differences become more pronounced, with cohabiting women 6 (14) percentage points more likely to be working at two (nine) months than their married peers. The corresponding figures for single mothers are 8 and 11 percentage points, respectively.11 These sizable increases may occur because cohabiting and single mothers face more financial pressure to work than married women.

Although the raw correlations in Figure 4 indicated a positive relationship between education and employment, the probit results in Table 1 tell a more nuanced story. The least-educated women are substantially (8 percentage points) less likely than mothers with some college-education (but no degree) to be working by nine months.12 In contrast, college graduates are predicted to work less often than their counterparts with only some college at two months, but the disparity disappears by nine months after birth. This result suggests that highly educated women initially return to work relatively slowly, which makes sense given their high likelihood of receiving maternity leave and also of having savings to draw upon to fund a period of unpaid leave.13 Similar reasoning may explain why women who have been to college but not received a degree are slightly less likely to work at two months than are high school graduates who did not attend college.

The probit estimates also reveal interesting differences in the relationship between maternal age and post-birth employment. By nine months, women under 20 or 20–24 years of age are significantly more likely to be working than are 25–29 year old mothers, while those aged 35 or older are significantly less likely to do so. Mothers aged 30–34 and 35 or more are also significantly less likely to work at two months post-birth, again possibly reflecting greater access to maternity leave and savings.

Consistent with other studies, the regression findings indicate that women are significantly more likely to be working at two months for second or later births than after the birth of their first child.14 These estimates control for other characteristics, including pre-birth employment, raising the possibility that mothers who work after a first birth are especially committed to the labor force and that this also translates into higher participation after later births.15 However, this is unlikely to provide an entire explanation, since mothers with second or later births are no more likely to work at nine months than women following first births (and those with third or later births are significantly less likely to do so). The more rapid initial return to work may occur because women who already have children may adjust more easily to the newborn and may have child care arrangements in place.

The final row of Table 1 confirms the strong positive relationship between pre-birth and post-birth employment. Holding other characteristics constant, women who were employed at birth are 39 percentage points more likely to be working by two months and 58 percentage points more probable at nine months than women who were not employed.

Conclusions

Our investigation of a new large and nationally representative study, the ECLS-B, confirms that over half (59 percent) of U.S. mothers worked nine months after births occurring in 2001. However, the analysis also reveals considerable variation in mothers’ employment timing across groups stratified by race/ethnicity, family structure, education, age, birth history, and prior employment. Among these, the single strongest factor predicting the return to work is whether the mother was working at the time of the birth.

One striking result is that women with greater resources – those who are married, have more than a Bachelor’s degree, and are aged 30 or older – are generally less likely to be working two months after a birth. These same groups are particularly likely to have access to maternity leave and savings to draw upon, suggesting that both factors play a role in permitting these women to remain home in the first few months after a birth. Black women also have relatively high probabilities of remaining at home for the first two months post-birth. This may similarly reflect greater availability of maternity leave as they are more likely (than whites) to work in large firms and unionized workplaces.

By nine months post-birth, other factors may come into play. Consistent with patterns seen for women with older children, black women with infants have relatively high probabilities of being employed at nine months, while the corresponding rates of Asian women are relatively low. Young, cohabiting and single mothers are more likely than their counterparts to work following births, possibly because these groups have limited resources available to finance periods away from jobs. Women with three or more children are less likely to work than those with one or two. So too are women with less than a high school education, who presumably would gain the least from working because of their low skill levels. Of course, our possible explanations for these patterns should be viewed as speculative at this point, pending a further and more detailed analysis of the sources of the observed differences.

The possibility of adverse health or developmental effects for children whose mothers work in the first month or two after a birth raises concern that women with the lowest levels of resources are least likely to avoid working in those months. For instance, only 23 percent of mothers with more than a bachelor’s degree are working by two months, compared with 31 percent of mothers with a high school degree or some college. It is plausible that if maternity leave rights were extended and the absences were paid, more women would stay home for the first two months, and the discrepancies found here in the timing of employment by family structure, age, and education might diminish.

It is less clear what factors explain the differences in work nine months after birth. Some groups with relatively low rates of employment (e.g. Asians, older, married, and those with three or more children) may have relatively strong preferences for being at home and so may be choosing not to work. However, other groups, such as women with less than a high school education, may be interested in working but unable to obtain jobs, or may find the payoff to employment to be too low, relatively to the associated costs.16 Given recent cutbacks in the availability of public assistance for non-working mothers, it is important to pursue policies to help such mothers improve their skills, alongside policies to help them access benefits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit that increase the rewards to low-wage work, and child care subsidies and tax credits that offset the costs of child care.

Finally, it is worth noting that the share of mothers working by nine months is notably higher in the United States than in peer industrialized countries. Our neighbor to the north, Canada, recently extended its paid maternity leave benefits to cover a full year post-birth. Under the previous regime, which offered six months paid leave, 60 percent of mothers were at work by nine months, a comparable figure to the U.S. However, when leave rights were extended to one year, the share of mothers working at nine months fell to only 20 percent, as mothers delayed returning to jobs.17 It is noteworthy that even after the extension, Canada’s maternity leave provisions are not unusually generous by international standards. Across the advanced industrialized nations that constitute the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the average length of job-protected (and mostly paid) maternity leave is 14 months. Most women take the full amount of leave to which they are entitled and then return to their pre-birth jobs. There is much that individual states and the Congress might learn from the experiences of other nations when considering changes in policies designed to assist mothers (and fathers) in balancing the needs of work and families.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for funding support from NICHD.

Appendix

A1.

Sample sizes and population proportions of demographic groups

| N | Weighted proportion | |

|---|---|---|

| All | 10,465 | 1.00 |

| White non-Hispanic | 4,805 | 0.57 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 1,705 | 0.14 |

| Hispanic | 1,865 | 0.23 |

| Asian | 1,365 | 0.03 |

| Other | 725 | 0.03 |

| Married | 6,739 | 0.65 |

| Cohabiting | 1,443 | 0.14 |

| Single mother | 2,179 | 0.20 |

| Other family type | 104 | 0.01 |

| Less than high school | 2,764 | 0.27 |

| High school | 2,252 | 0.22 |

| Some college | 2,688 | 0.26 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1,657 | 0.15 |

| More than bachelor’s degree | 1,104 | 0.09 |

| Age less than 20 | 784 | 0.07 |

| Age 20–24 | 2,578 | 0.24 |

| Age 25–29 | 2,516 | 0.26 |

| Age 30–34 | 2,655 | 0.25 |

| Age 35+ | 1,932 | 0.17 |

| First-born | 3,837 | 0.41 |

| Second-born | 3,583 | 0.34 |

| Third-born or more | 3,045 | 0.26 |

| Not employed at birth | 5,228 | 0.49 |

| Employed at birth | 5,237 | 0.51 |

A2.

Proportion of mothers working in first 9 months after birth: By race/ethnicity

| Months after birth | All | White | Black | Hispanic | Asian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| 2 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.22 |

| 3 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.37 |

| 4 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 0.42 |

| 5 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.44 |

| 6 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| 7 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.47 |

| 8 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.49 |

| 9 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.51 | 0.49 |

A3.

Proportion of mothers working in first 9 months after birth: By family type

| Months after birth | All | Married | Cohabiting | Single mother |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| 2 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.28 |

| 3 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.41 |

| 4 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.48 |

| 5 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.51 |

| 6 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| 7 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.58 |

| 8 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| 9 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.62 | 0.61 |

A4.

Proportion of mothers working in first 9 months after birth: By maternal education

| Months after birth | All | Less than high school | High school | Some college | Bachelor’s degree | More than bachelor’s degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| 2 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.23 |

| 3 | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| 4 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.55 |

| 5 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.60 |

| 6 | 0.54 | 0.40 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.59 | 0.64 |

| 7 | 0.56 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.66 |

| 8 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.68 |

| 9 | 0.59 | 0.47 | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.68 |

A5.

Proportion of mothers working in first 9 months after birth: By maternal age at birth

| Months after birth | All | Less than 20 | 20–24 | 25–29 | 30–34 | 35+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| 2 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.24 |

| 3 | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.41 |

| 4 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.48 |

| 5 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.52 |

| 6 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.55 |

| 7 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.56 |

| 8 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.58 |

| 9 | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.59 |

A6.

Proportion of mothers working in first 9 months after birth: By child birth order

| Months after birth | All | First-born | Second-born | Third-born or more |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| 2 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.25 |

| 3 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.36 |

| 4 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.41 |

| 5 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.43 |

| 6 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.46 |

| 7 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.47 |

| 8 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.49 |

| 9 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.50 |

References

- 1.See Bethel, Green, Kalton, & Nord, 2005for a detailed description of the ECLS-B study design.

- 2.Prior empirical studies of post-birth employment include: Desai Sonalde, Waite Linda. Women’s employment during pregnancy and after the first birth: Occupational characteristics and work commitment. American Sociological Review. 1991;56(4):551–566.Leibowitz Arleen, Klerman Jacob Alex, Waite Linda. Employment of new mothers and child care choice. Journal of Human Resources. 1992;27(1):112–133.; Klerman and Leibowitz, 1994; Smith, Downs, and O’Connell, 2001; and Berger Lawrence, Waldfogel Jane. Maternity leave and the employment of new mothers in the United States. Journal of Population Economics. 2004;17:331–349.See also the literature review by Kristin Smith and Amara Bachu, 1999, “Women’s labor force attachment patterns and maternity leave: A review of the literature,” U.S. Bureau of the Census Population Division Working Paper No. 32; U.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC.

- 3.All proportions and estimates in this article are adjusted to account for over-sampling of minority groups and complex survey design.

- 4.The labor force participation rate for 1968 is from U.S. Bureau of the Census (2001), “Fertility Tables 2000,” retrieved on September 12, 2007 from www.census.gov. For an excellent overview of trends in maternity leave and employment from 1961 to 1995, see Kristin Smith, Barbara Downs, and Martin O’Connell, 2001, “Maternity leave and employment patterns: 1961–1995,” Current Population Reports P70–79. Available from the U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC.

- 5.See Jane Lawler Dye, 2005, “Fertility of American Women: June 2004,” Current Population Reports P20–555, retrieved on December 12, 2007 from http://www.census.gov/prod/2005pubs/p20-555.pdf; U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2007, “Charting the U.S. Labor Market in 2006,” retrieved on November 15, 2007 from http://www.bls.gov/cps/labor2006.home.htm; and Sharon Cohany and Emy Sok, 2007, “Trends in labor force participation of married mothers of infants,” Monthly Labor Review, February 2007, pp. 9–16.

- 6.See Alex Klerman Jacob, Leibowitz Arleen. The work-employment distinction among new mothers. Journal of Human Resources. 1994;24(2):277–303., for a useful discussion of the distinction between labor force participation, employment, and being at work among new mothers.

- 4.The ECLS-B sampled births from Vital Statistics records and is comprised of children born in 2001 who were alive at the baseline interview. Baseline parent interviews and child assessments were done when the child was approximately nine months old (there are interviews at 24 months, pre-school entry, and kindergarten, which we do not use here). The nine-month (baseline) ECLS-B interview consists of a computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) administered to the parent respondent (the biological mother in 99% of the cases), as well as direct assessments of the child’s development, caregiver-child interaction patterns, a self-administered questionnaires for the resident father or male guardian, as well as the nonresident father if permission was granted by the mother and he was located. See Bethel, Green, Kalton, & Nord, 2005 for a detailed description of the ECLS-B study design.

- 5.Prior empirical studies of post-birth employment include: Desai Sonalde, Waite Linda. Women’s employment during pregnancy and after the first birth: Occupational characteristics and work commitment. American Sociological Review. 1991;56(4):551–566.Leibowitz Arleen, Klerman Jacob Alex, Waite Linda. Employment of new mothers and child care choice. Journal of Human Resources. 1992;27(1):112–133.Klerman and Leibowitz, 1994; Smith, Downs, and O’Connell, 2001; and Lawrence Berger and Jane Waldfogel, 2004, “Maternity leave and the employment of new mothers in the United States,” Journal of Population Economics, 17, pp. 331–349. See also the literature review by Kristin Smith and Amara Bachu, 1999, “Women’s labor force attachment patterns and maternity leave: A review of the literature,” U.S. Bureau of the Census Population Division Working Paper No. 32; U.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC.

- 6.See, for example, Mosisa Abraham, Hipple Steven. Trends in labor force participation in the United States. Monthly Labor Review. 2006 October;:35–57.

- 7.Previous research has consistently found that eligibility for maternity leave increases with the level of maternal education. See for example Cantor David, Waldfogel Jane, Kerwin Jeffrey, Wright Mareena McKinley, Levin Kerry, Rauch John, Hagerty Tracey, Kudela Martha Stapleton. Balancing the Need of Families and Employers: Family and Medical Leave Surveys, 2000 Update. Rockville, MD: Westat; 2000. . See also Klerman and Leibowitz, 1994; and Smith, Downs, and O’Connell, 2001.

- 8.See, for example, Klerman and Leibowitz, 1994; and Smith, Downs, and O’Connell, 2001.

- 9.See, for example, Berger and Waldfogel, 2004; using data for 1988 to 1996 from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, they find that 80 percent of women who were employed pre-birth were working by nine months, compared to just have of those who were not employed before giving birth. See also Smith, Downs, and O’Connell, 2001.

- 10.Cantor et al., 2000, find that black women have higher rates of leave coverage than white women. Berger and Waldfogel, 2004, using data from the NLSY, show that women with maternity leave rights are more likely to work in the first year, but return more slowly in the initial months.

- 11.The regression models also control for “other family type”, a small category that includes households where the mothers is not married, cohabiting, or single. We do not report the results for this category because the cell size is very small (N=104).

- 12.A similar finding was reported by Klerman Jacob Alex, Leibowitz Arleen. Job continuity among new mothers. Demography. 1999;36(2):145–155., in their analyses of women in 1990 from the NLSY and the June Current Population Survey. See also Smith, Downs, and O’Connell, 2001; and Berger and Waldfogel, 2004.

- 13.See Cantor et al., 2000.

- 14.See, for example, Berger and Waldfogel, 2004, who find that women having a second or higher birth return more quickly than those having a first birth.

- 15.Klerman and Leibowitz, 1999, suggest that women divide themselves after a first birth into those who will continue working and those will not, with the former group being more likely to work after subsequent births as well.

- 16.On the importance of child care in women’s employment decisions post-birth, see Klerman Jacob Alex, Leibowitz Arleen. Child care and women’s return to work after childbirth. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings. 1999;80(2):284–292.and Leibowitz, Klerman, and Waite, 1992.

- 17.See Michael Baker and Kevin Milligan, 2007, “Maternal employment, breastfeeding, and health: Evidence from maternity leave mandates,” NBER Working Paper No. 13188, retrieved on December 15, 2007, from www.nber.org.