Abstract

Objective

To estimate whether tampon users are more likely to select the contraceptive vaginal ring than combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs).

Methods

The Contraceptive Choice Project is a longitudinal study of 10,000 St. Louis-area women promoting the use of long-acting, reversible methods of contraception and evaluating user continuation and satisfaction for all reversible methods. We performed univariable and multivariable analyses of the 311 women who were asked about tampon use at the time of enrollment and who chose the contraceptive vaginal ring or OCPs to assess the association of tampon use and choice of combined hormonal method.

Results

Among contraceptive vaginal ring and OCP users, 247 (79%) reported using tampons. Contraceptive vaginal ring users were not significantly different than OCP users in terms of age, race or ethnicity, marital status, insurance, BMI, and parity. Adjusted analysis indicates tampon users were more likely to choose the contraceptive vaginal ring instead of OCPs (adjusted RR=1.34; 95%CI: 1.01–1.78). Women with previous contraceptive vaginal ring experience were also more likely to choose the contraceptive vaginal ring (adjusted RR=1.96; 95%CI: 1.6–2.4). Recent OCP use did not influence method choice.

Conclusion

In our baseline analysis of the Contraceptive Choice Project, tampon users were more likely to choose the contraceptive vaginal ring than OCPs. Use of tampons could be considered an indicator for the initial acceptability of the contraceptive vaginal ring, but all women should be offered the contraceptive vaginal ring regardless of experience with tampon use.

Introduction

Since unintended pregnancies account for almost half of all pregnancies in the United States (1), investigation into new methods of contraception intended to improve compliance is essential. While combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) have been a mainstay in fertility management for several decades, their efficacy relies on daily pill intake which may be difficult for some patients to adhere (2). The contraceptive vaginal ring (CVR), however, is inserted into the vagina by the woman herself and only needs to be changed once a month.

Many clinicians feel reluctant to offer the CVR to patients they believe would be uncomfortable touching their own genitalia, particularly those who don’t use tampons. In a randomized trial, Schafer and colleagues found neither tampon use nor discomfort touching their own genitalia predicted dissatisfaction or discontinuation of the CVR (3). Given the paucity of published data addressing patient comfort with vaginal contraceptive methods and tampon use, we proposed an analysis to estimate the association between tampon use and choice of the CVR or COCs in participants of the Contraceptive Choice Project. We hypothesize that women who use tampons will be more likely to select the ring compared to COCs, even after we control for other demographic and reproductive characteristics.

Materials and Methods

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of baseline demographic data obtained during participant enrollment in The Contraceptive Choice Project. The Contraceptive Choice Project is a prospective, observational study designed to promote the use of long-acting reversible methods of contraception (LARC) and evaluate use, satisfaction and continuation across both LARC and non-LARC methods in a cohort of 10,000 women. Women are offered counseling, reversible contraception of their choice, sexually transmitted infection screening and treatment, and followed for 3 years with telephone interviews. The enrollment phase began on August 1, 2007 and is projected to occur over four years. The Choice protocol was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Research Protection Office prior to initiation of participant recruitment.

Women learn of Choice through information posted in selected St. Louis area clinics and by word of mouth. Eligibility screening occurs in person at recruitment sites or on the telephone by calling the main Choice telephone number. Screening encounters are conducted by a trained staff person who asks a series of questions to determine eligibility. Inclusion criteria are: age 14–45 years, residence in the St. Louis City or County or seeking services at designated recruitment sites, willing to switch or initiate a new contraceptive method, sexually active with a male partner within 6 months, and able to consent in English or Spanish. Women who are surgically sterile or desire pregnancy within 1 year are excluded. If the woman is an eligible candidate, the screener offers the opportunity to enroll. This encounter is documented on a standardized data collection form.

Enrollment in Choice occurs during an in-person session. Informed consent for participation in Choice is only obtained after the woman has completed contraceptive counseling. The decision to obtain informed consent for the study was made based on the recommendation of our human research projection office colleagues. Contraceptive counseling is provided to women prior to study enrollment in the Choice Project by either (1) staff employed by the community-based recruitment clinic as part of the woman’s routine family planning or gynecology visit or (2) trained contraceptive counselors at the University-based recruitment site. Each woman receives counseling according to protocols established by each clinic and includes identifying a method that is appropriate for her and available through the Choice Project. Questions, misinformation, and other concerns the potential participant may have are addressed at this time to facilitate her informed decision making process. Following counseling she undergoes the informed consent process for the research study which focuses on the follow-up surveys to assess method continuation and satisfaction.

The study counselor collects clinical information on each woman using a standardized form to identify contraindications or conditions that may influence use of a particular contraceptive method. Approval for the method is obtained from a clinician at the end of contraceptive counseling.

For minors under 18 years, their assent and the consent of one parent or legal guardian are obtained. In situations where the minor does not know the whereabouts of their parent or legal guardian or where it would not be in the minor’s best interest to contact them, IRB approval to waive parental consent has been obtained.

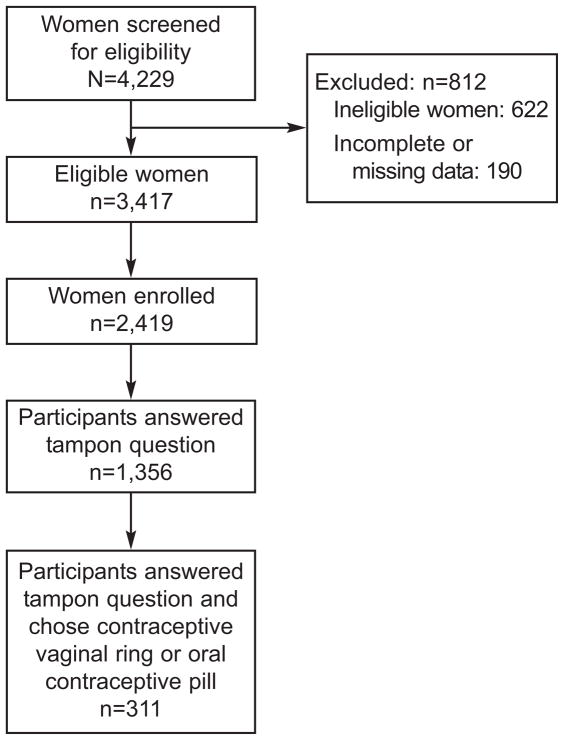

The data for this analysis was collected in the baseline questionnaires of the first 2419 participants. The enrollment of this cohort was completed in December, 2008. Our original questionnaire did not contain a question about tampon use; this question was later added. It asked participants if, during their periods they used tampons: all the time, more than half the time, less than half the time, don’t use tampons. For the purpose of this analysis, these categories were collapsed into two categories: tampon use yes if participants answered “all the time”, “more than half the time”, or “less than half the time”, and tampon use no if they responded “don’t use tampons.” All participants in this analysis were from the women enrolled who had a response to the tampon use questionnaire and chose either the CVR or COCs (See Figure 1). Demographic information obtained included: age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, marital status, income, insurance status, age at menarche, gravidity, parity, and body mass index (BMI; underweight < 18.5; normal 18.5–24.9; overweight 25.0–29.9; obese 30.0 kg/m2 or greater). Sexual history information obtained included: number of sexual partners in the previous 30 days, condom use and perceived partner willingness to use condoms, ever contraception use and previous contraception choices, and douching activity. Information about factors contributing to method choice was also obtained, including: cost, effectiveness, recommendation by other physicians and friends, ease of use, approval by sexual partner, safety, and side effects.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Study Participants

Demographic characteristics were described using frequencies, percents, and means. Possible differences between the two groups were analyzed using chi-square tests, t-tests, and Fisher exact tests. Multivariable Poisson regression models with robust error variance were used to estimate relative risk and 95% confidence intervals for the relationship between method choice and tampon use. This analytic approach provides an unbiased estimate of the relative risk when the outcome is common (greater than 10%) (4, 5). Covariates considered in the adjusted multivariable analysis include: current condom use, ever vaginal ring use, cost of contraceptive method, knowledge of effectiveness of COCs, age, education, and recent pill use. A p-value of less than 0.05 was used to define statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Preliminary analysis of Choice data showed an 11% overall acceptance rate of the CVR. Based on this information, we assumed a CVR acceptance rate of 10% in women not using tampons, and considered a relative risk of 2.5 for CVR in tampon users to be clinically relevant. We calculated a sample size of 112 per group with 80% power (alpha = 0.05) based on these assumptions.

Results

Of the first 2419 participants, 284 (12%) chose the CVR and 302 (12%) chose COCs as their baseline method of contraception. The tampon question was asked of 1356 women, with 1035 (76%) participants reporting tampon use. Of the 1035 participants who reported tampon use, 133 (13%) chose the CVR and 114 (11%) chose COCs. Of the 321 participants who do not use tampons, 23 (7%) chose the CVR and 41 (13%) chose COCs (P=0.01).

In our subset for this analysis (Table 1), 311 participants chose either the CVR (n=156) or COCs (n=155), and 247(79%) reported tampon use. Of the 247 tampon users who selected COCs or CVR, 133 (54%) chose the CVR. Of the 64 participants not using tampons, 23 (36%) chose the CVR. Most participants were less than 25 years of age (69%), single (75%) and nulliparous (72%). White and African American participants were similarly represented. Over half the participants had insurance (57%), while 37% didn’t have any insurance and 7% had Medicaid. Almost half the participants had a BMI of 18.5–24.9, indicating a normal weight. Most of the other half was overweight or obese (23% and 22% respectively).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics

| Variables | COC N=155 |

CVR N=156 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean | 23.3 (5.3) | 24.0 (4.0) | 0.17** |

| Percentages | |||

| Age | |||

| <25 | 71.0 | 66.0 | 0.35 |

| 25+ | 29.0 | 34.0 | |

| Race | |||

| Black/African American | 45.8 | 39.7 | 0.48 |

| White | 43.2 | 50.0 | |

| Other | 11.0 | 10.3 | |

| Education | |||

| ≤ High School | 33.6 | 19.9 | <.01 |

| Some college/College/Graduate degree | 66.5 | 80.1 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single/Never married | 78.1 | 71.8 | 0.32* |

| With partner/Married | 21.3 | 26.3 | |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 0.6 | 1.9 | |

| Income | |||

| None | 19.0 | 11.5 | 0.12 |

| $1–$800 per month | 36.6 | 32.1 | |

| $801–$1,600 per month | 29.4 | 34.6 | |

| $1,601+ per month | 15.0 | 21.8 | |

| Missing, n | 2 | 0 | |

| Insurance | |||

| None | 40.8 | 32.9 | 0.26* |

| Medicare/Disability/Medicaid | 7.2 | 5.8 | |

| Private/Student/Parent’s | 52.0 | 61.3 | |

| Missing, n | 3 | 1 | |

| BMI, mean | 25.3 (7.2) | 25.7 (6.8) | 0.68** |

| Below 18.5 (Underweight) | 10 (6.5) | 11 (7.1) | 0.37* |

| 18.5 – 24.9 (Normal) | 82 (52.9) | 68 (43.9) | |

| 25.0 – 29.9 (Overweight) | 30 (19.4) | 41 (26.5) | |

| 30.0 and Above (Obese) | 33 (21.3) | 35 (22.6) | |

| Missing, n | 0 | 1 | |

| Gravidity | |||

| 0 | 54.2 | 47.4 | 0.54 |

| 1 | 18.7 | 17.9 | |

| 2 | 13.6 | 16.7 | |

| 3+ | 13.6 | 17.9 | |

| Parity | |||

| 0 | 74.8 | 69.2 | 0.51 |

| 1 | 14.2 | 18.6 | |

| 2+ | 11.0 | 12.2 | |

| Tampon use as chosen method at baseline | |||

| No | 26.5 | 14.7 | <.01* |

| Yes | 73.6 | 85.3 | |

| Total sexual partners in the last 30 days | |||

| 0 | 21.2 | 16.1 | 0.47* |

| 1 | 71.5 | 77.4 | |

| 2+ | 7.3 | 6.5 | |

| Missing, n | 4 | 1 | |

| Ever contraception use | |||

| No | 4.5 | 0.6 | 0.04* |

| Yes | 95.5 | 99.4 | |

| Previous contraceptive choices, ever use | |||

| Vaginal ring | |||

| No | 87.8 | 55.8 | <.01* |

| Yes | 12.2 | 44.2 | |

| Missing, n | 8 | 2 | |

| Birth control pills | |||

| No | 2.3 | 18.7 | 0.44 |

| Yes | 77.7 | 81.3 | |

| Missing, n | 7 | 1 | |

| Recent pill use, prior to study entry | |||

| No | 78.4 | 87.0 | 0.04 |

| Yes | 21.6 | 13.0 | |

| Missing, n | 7 | 2 | |

| Recent vaginal ring use, prior to study entry | |||

| No | 99.3 | 83.8 | <.01 |

| Yes | 0.7 | 16.2 | |

| Missing, n | 8 | 2 | |

| Current condom use | |||

| No | 39.4 | 53.8 | 0.01 |

| Yes | 60.6 | 46.2 | |

| Douching during past 30 days | |||

| No | 94.2 | 93.6 | 1.0* |

| Yes | 5.8 | 6.4 | |

| Missing, n | 1 | 0 |

Fishers exact test for computing p-values

Student t-test to compare means

In the univariable analysis comparing choice of the CVR or COCs, tampon users were more likely to choose the CVR over COCs (54% vs. 46%). Non-tampon users were more likely to choose COCs instead of CVR (64% vs. 36%). When we controlled for current condom use, ever use of CVR, method cost, age, education, and knowledge of birth control pill effectiveness (Table 2), tampon users were 34% more likely to choose the CVR (RR=1.34; 95% CI 1.01–1.78). Condom use was associated with a reduced likelihood of CVR use compared to COCs in the univariable analysis and adjusted analysis (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.61–0.93). Participant concern about cost was negatively associated with CVR choice (RR 0.55, CI 0.35–0.86), and participants who correctly estimated the effectiveness of COCs were more likely to choose the CVR (RR 1.26, CI 1.01–1.57). While women with greater education appeared more likely to choose the CVR over COCs, education did not remain a statistically significant factor in the multivariable analysis (RR 1.31; 95% CI 0.97–1.76). Additionally, age was not associated with CVR use in our multivariable analysis.

Most participants (79.5%) reported ever using birth control pills while only some (17.2%) reported recent use. In contrast, far fewer women (28.6%) reported ever using the CVR and even fewer (8.6%) reported recent use. Ever CVR users were more likely to choose the CVR (RR 1.96, CI 1.60–2.40).

Discussion

In this analysis, we found tampon users were more likely to choose the CVR as their baseline contraceptive method; whereas women who do not use tampons were more likely to choose COCs. Although we found an association between tampon use and method selection, Schafer and colleagues found that tampon use was not predictive of continuation and satisfaction with the CVR. It is important to note that their study was a randomized-controlled trial where method was randomly assigned; therefore correlates of method selection could not be ascertained.(2)

In addition to tampon use, familiarity with contraceptive methods may influence a woman’s method selection within the Choice Project. Most participants answering the tampon question had previously used some form of contraception and most had prior experience with COCs. Almost a third of participants in this dataset had used the CVR in the past. Our finding that prior users of the CVR were twice as likely to choose the CVR may indicate a high acceptability and satisfaction with this method and is consistent with prior acceptability studies. Dieben and colleagues found an overall satisfaction rate of 85% and 90% of their participants planning to recommend the CVR to friends. (6)

We also found condom use was negatively associated with choosing CVR among our participants. Roumen and colleagues found that almost 20% of their study participants noted feeling the ring during intercourse (7). It is possible that having two objects in the vagina at the same time may be physically or psychologically uncomfortable to the woman or her partner.

Because women in this study could choose any method without having to worry about cost, we observed approximately the same percentage of women choosing to use the CVR (11%) or COCs (12%). However, in the real world these two methods vary significantly in cost including the out-of-pocket expense paid by women. The CVR is significantly more costly than generic COCs and we did observe a 50% reduction in the choice of the CVR among participants who perceived cost as a factor.

Our study is not without limitations. Our analysis only investigated predictors of baseline uptake of contraceptive method and does not answer the question of whether tampon use is predictive of CVR continuation and satisfaction. Satisfaction with a contraceptive method is important as up to 31% of women will discontinue their reversible contraceptive method within 6 months of initiation.(8) Although prior research found that tampon use is not predictive of continuation or satisfaction (2), future analyses of the Choice Project may find that tampon use and ability to select the contraceptive method may both influence satisfaction and continuation with the CVR.

The CVR is an effective contraceptive method with reported high satisfaction and continuation. Our study suggests that information about tampon use is one of the factors in a woman’s decision to use the CVR and could be considered during discussions with her medical provider. Tampon use should not be the only criterion on which recommendation or prescription of the CVR is based.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by: an anonymous foundation, the Midcareer Investigator Award in Women’s Health Research (K24 HD01298), Clinical and Translational Science Awards (UL1RR024992), and grant numbers KL2RR024994 and K3054628 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Gina Secura: Money paid to her for employment by Washington University School of Medicine. Jenifer E. Allsworth: grant paid to her institution through NIH training grant NCRR KL2 024994. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in Rates of Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 1994–2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38(2):90–96. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halpern V, Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Gallo MF. Strategies to improve adherence and acceptability of hormonal methods of contraception. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(2):Art. No.: CD004317. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004317.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schafer JE, Osborne LM, Davis AR, Westhoff C. Acceptability and satisfaction using Quick Start with the contraceptive vaginal ring versus an oral contraceptive. Contraception. 2005;73:488–492. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mcnutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157:940–943. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998 Nov 18;280(19):1690–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dieben TOM, Roumen FJME, Aptar D. Efficacy, cycle control, and user acceptability of a novel combined contraceptive vaginal ring. Obstetrics and Gynecology Sept. 2002;100(3):585–593. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roumen FJME, Apter D, Mulders TMT, et al. Efficacy, tolerability and acceptability of a novel contraceptive vaginal ring releasing etonogestrel and ethinyl oestradiol. Human Reproduction. 2001;16:469–76. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trussell J, Vaughan B. Contraceptive failure, method-related discontinuation and resumption of use: results from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;31(2):64–72. 93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]