Abstract

Studies of human tissue show that many chronic pain syndromes are accompanied by abnormal increases in numbers of peripheral sensory nerve fibers. It is not known if sensory nerve sprouting occurs as a result of inflammation present in these conditions, or other factors such as infection or extensive tissue damage. In the present study, we used a well established model of inflammation to examine cutaneous innervation density in relation to mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity. Adult female rats were ovariectomized to eliminate fluctuations in female reproductive hormones and one week later, a hind paw was injected with carrageenan or saline vehicle. Behavioral testing showed that saline vehicle injection did not alter thermal or mechanical thresholds compared to pre-injection baselines. Carrageenan injections resulted in markedly reduced paw withdrawal thresholds at 24 and 72 h after injection; this was accompanied by increased mechanical sensitivity of the contralateral paw at 72h. Analysis of innervation density using PGP9.5 as a pan-neuronal marker at 72h showed that inflammation resulted in a 2-fold increase in cutaneous innervation density. We conclude that inflammation alone is sufficient to induce sprouting of sensory cutaneous axon endings leading local tissue hyperinnervation, which may contribute to hypersensitivity that occurs in painful inflammatory conditions.

Keywords: Pain, sensory nerves, axon sprouting, skin

Introduction

Mechanisms of chronic pain are poorly understood, and several factors have been identified that may contribute to enhanced peripheral nociceptor sensitivity. Persistent pain is postulated to involve alterations of neuronal ion channels [4, 11] and membrane receptors [41], and may involve recruitment of otherwise dormant nociceptors [23]. There also is evidence that sensitization of both peripheral [39] and central neurons [38, 40] may contribute to hyperalgesia [33] and allodynia [24]. Therefore, multiple factors are thus far implicated in the establishment of chronic pain.

Accumulating evidence in humans suggests that structural remodeling of peripheral sensory fibers may be an additional factor in some types of pain. For example, peripheral neuropathic pain is often accompanied by decreased cutaneous axon density, leading to centrally mediated pain [39]. Conversely, an abnormal increase in numbers of nerve fibers (hyperinnervation) is reported to occur in several types of musculo-skeletal pain including Achilles tendinitis [2, 30], chronic knee pain [28, 29] and degenerative disk pain [8, 12]. Other pain syndromes associated with hyperinnervation include chronic appendicitis [10], deep infiltrating endometriosis [35], mastodynia [14], and vulvodynia [5, 6, 34]. Therefore, sensory hyperinnervation appears to be a common feature associated with a number of chronically painful conditions.

While the mechanisms leading to hyperinnervation are unclear, inflammation is a common thread in all disease syndromes in which hyperinnervation is reported to occur. Thus, inflammation may be an initiating factor leading to sensory axon proliferation. The inflammatory milieu contains cytokines, chemokines, and growth factor proteins [22] which, alone or in combination, may promote sensory axon sprouting. However, it is as yet unclear whether hyperinnervation occurs as a result of inflammation or is secondary to extensive tissue injury and repair, infection, or degenerative processes that also occur in these human disease conditions. In the present study we assessed whether hyperinnervation occurs in a well-established model of inflammation and accompanies behavioral hypersensitivity.

Materials and methods

All animal protocols and procedures were in accordance with the NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Kansas University Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee. Twelve female Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) at approximately 60 d and weighing 190 – 200 g were anesthetized (i.p. injection of 70 mg/kg ketamine HCl [Ketaject] and 6 mg/kg xylazine [Xyla-Ject]) and bilaterally ovariectomized under aseptic conditions; ovariectomy eliminates cyclic fluctuations in serum reproductive hormone levels that are known to influence behavioral sensitivity [9, 27]. After 7 days, rats were randomly distributed to two groups of 6 each; one received a subcutaneous plantar injection into the left paw of 0.1 ml of 2% (w/v) λ-carrageenan (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 0.9% sterile saline, while rats in the second group received identical injections of sterile isotonic saline vehicle. All injections were made by inserting a 29 gauge needle into the posterior region of the plantar surface and delivering the injectate into the approximate center of the plantar surface.

Behavioral sensitivity was assessed by first measuring mechanical withdrawal threshold (MWT) using an electronic von Frey anesthesiometer (Model 2390; IITC Inc., Woodland Hills, CA) and then thermal withdrawal latency (TWL) using a Paw Thermal Stimulator Instrument (University of California, San Diego). All behavioral tests were performed between 8:30 – 11:30 AM. For MWT, rats were acclimated for 30 min inside a Plexiglas box on a steel mesh floor and analyses performed using an electronic von Frey apparatus. Stimulation was applied to the center of the hind paw in an upward motion with the von Frey filament until foot withdrawal occurred, and withdrawal threshold was automatically recorded. The procedure was repeated three times at 3–5 min intervals for each hind paw and the average calculated. Rats were then acclimated for 30 min in individual Plexiglas boxes on a glass plate maintained at 30°C. The time to withdraw the hind paw from a high-intensity light beam was recorded automatically. The test was performed three times at 3–5 min intervals on each paw, and the average value calculated for each session. Behavioral tests were performed at 24h prior to (n=6) and 24 and 72h post-carrageenan or vehicle injection (n=3 each). Following behavioral testing at 72h, rats were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (150mg/kg i.p.), and plantar surface skin from both hind paws removed and fixed in Zamboni’s fixative at 4°C overnight, rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (0.01M, pH 7.4) for several days, and cryoprotected overnight in 20% sucrose. Tissues were mounted in Tissue Tek OCT compound, snap-frozen and cryosectioned at 20 μm perpendicular to the long axis of the paw. Sections collected from the center of the region where the injectate was deposited (4 mm proximal to the junction with the toes) were blocked with 10% normal goat serum (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratory, West Grove, PA), incubated overnight with rabbit IgG directed against the pan-neuronal marker PGP9.5 (1:400; Serotec, Raleigh, NC), rinsed with PBS containing 0.3% triton X-100, and incubated with Cy2 conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Jackson) at room temperature for 1 h. Negative controls included primary antisera preabsorbtion to blocking peptides, heat inactivation and antibody omission.

Average innervation density was measured in 3 sample fields per section; one sample field (149,188 μm2) was from the section’s center, directly over the site of injectate deposition, and one each from the lateral parts of the section corresponding to the margins of the inflamed tissue. For each subject, analyses were obtained from 3 sections taken at 1 mm intervals, with 6 subjects each analyzed in the saline- and carageenan- injected groups. Images were captured with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope using a Nikon Fluor 20X/0.50 DIC M/N2 objective, and a Nikon DSFi1 camera. A stereological grid (AnalySis v.3.2) with intersects at 10 μm intervals was superimposed over each image. The number of intersects overlying the epidermis was counted, and the number of points overlying PGP-immunoreactive (-ir) axons was also determined in each field. Apparent percentage of epidermal area occupied by PGP-ir axon was calculated by dividing intersects overlying axons by intersects overlying the tissue within the sample field. To obtain the apparent area occupied by axons, the fraction of epidermal tissue occupied by PGP-ir nerves was multiplied by the total area of the epidermal tissue compartment within each sample area. Values were normalized to the length of epidermis sampled within each field and expressed as PGP9.5-ir axon area (μm2) per mm. Values from the 9 sample regions for each paw were averaged. Data obtained from behavioral and stereological analyses are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made using Student’s t-test or one way ANOVA (all data were normally distributed). Post-hoc comparisons were made using the Student-Newman-Keuls test and differences considered significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Intraplantar saline injections resulted in transient mild vasodilation shortly after injection, with no obvious inflammation at 24h or 72h. Carrageenan injection resulted in marked vasodilation followed by significant edema and paw licking though 24h, resolving slightly by 72h post-injection. The contralateral paws appeared normal and unaffected.

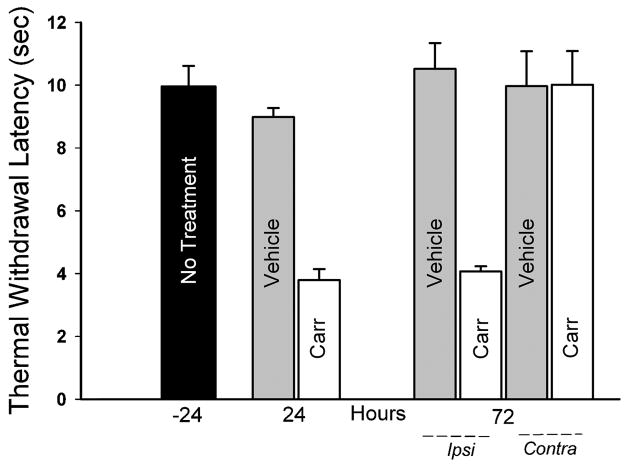

At 24 h prior to treatment, TWL was 10.0±0.7 sec for the left paw (Fig. 1) and 10.5±0.4 sec for the right paw (not shown). TWL of the saline-injected left paws were comparable to the uninjected control paws, and were unchanged through 72h post-saline injection (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Thermal sensitivity was assessed by measuring time required for rats to withdraw their paws in response to warming (Thermal Withdrawal Latency). Baseline measurements were made from the left paw of 6 rats 24 h prior to injections (No Treatment, −24). Measurements from the left hind paw 24 hours after saline (Vehicle, n=3) or carrageenan (Carr, n=3) injection showed increased sensitivity. At 72 h after injection, the paw ipsilateral (Ipsi) to carrageenan injection showed sustained hypersensitivity relative to ipsilateral vehicle injection and baseline measurements. Responses from paws contralateral to injection (Contra) were comparable. Carrageenan vs. Vehicle at 24–72 h, p<0.001 by ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls test.

Carrageenan injection markedly decreased TWL relative to uninjected and saline injected paws. TWL following carrageenan injection was reduced by 58% relative to saline injection after 24h, and remained decreased for 72h (Fig. 1, p<0.001 at 24h and 72h). No differences were observed in TWL measured at 72 h from hind paws contralateral to carrageenan injection.

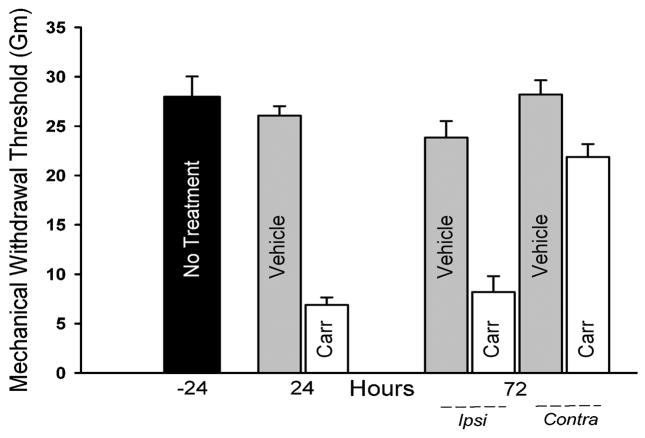

Mechanical withdrawal thresholds measured from the left hind paw prior to injection were 28.0±2.1gm (Fig. 2), which was comparable to the contralateral paw (not shown). In vehicle-injected rats, no significant differences were observed for MWT at 24h and 72h post-injection. Carrageenan injection resulted in a significant decrease in MWT relative to saline injection at 24h (6.8±0.8 vs.26.1±0.9 gm; p<0.001) and 72h (8.2 ±1.6 vs 23.8±1.7 gm; p<0.001; Fig. 2). MWTs from hind paws contralateral to carrageenan injection were lower than those contralateral to vehicle injection at 72h (p = 0.009, Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanical sensitivity was assessed by electronic von Frey anesthesiometry to determine force required to elicit a withdrawal response. Baseline measurements were obtained from the paw 24 h prior to injections (No Treatment, −24, n=6). Measurements from the left hind paw 24 hours after injection showed heightened sensitivity following carrageenan (Carr, n=3) relative to saline (Vehicle, n=3) injection (p<0.001). At 72 h after injection, the paw ipsilateral (Ipsi) to carrageenan injection showed continued hypersensitivity relative to ipsilateral vehicle injection and baseline measurements (n=3/group, p<0.001). The paw contralateral (Contra) to the carrageenan injection showed increased sensitivity relative to the paw contralateral to saline injection at 72 h (p = 0.009).

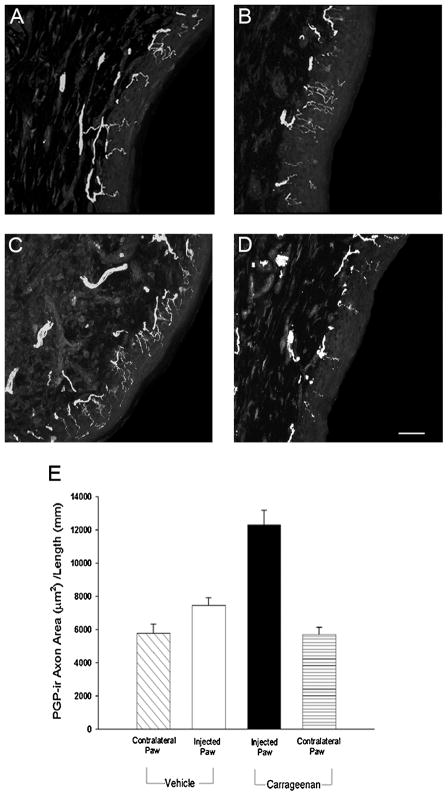

Sections of the plantar skin from uninjected right paws immunostained for PGP9.5 showed nerve fiber bundles oriented longitudinally along the epidermal-dermal interface, with fine axonal branches extending perpendicularly for variable distances into the epidermis; smaller numbers of fiber bundles were present within the dermal region near the epidermis (Fig. 3A). The density of innervation, as determined by sectional axon area per unit length of skin, did not differ between contralateral paws of rats injected with either saline or carrageenan (Fig. 3A, D, E). Saline injection (Fig. 3B) did not significantly affect total innervation density of the epidermis compared to the uninjected paw skin (Fig. 3E). In contrast, carrageenan injection (Fig. 3C) resulted in a 2-fold increase in innervation relative to the contralateral uninjected paw (Fig. 3D, E; p<0.001) and approximately a 70% increase (p = 0.022) over that of saline injection (Fig. 3B, E).

Figure 3.

Confocal micrographs of PGP9.5-immunoreactive axons in footpad epidermis 72 h following saline or carrageenan injection. A) Uninjected footpad epidermis contralateral saline injection. B) Saline injected footpad epidermis. C) Carrageenan injected footpad epidermis. D) Uninjected footpad epidermis contralateral to carrageenan injection. Scale bar in D = 40 μm. E) Quantitative analysis of footpad epidermis revealed that axon density was increased following carrageenan injection relative to the contralateral foot or saline injection (p <0.001, n=6 per group).

Discussion

Carrageenan injection into the rat plantar hind paw is a well established model of inflammation. Carrageenans are linear sulfated polysaccharides derived from red seaweeds, which possess strong inflammatory properties. Carrageenan injections into the plantar aspect of the rodent paw were first used by Winter et al. as an edema-based assay for evaluating anti-inflammatory drugs [37]. Subsequently, this model has been used widely to evoke thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia in rodents [17, 25, 31]. Following carrageenan injection, edema and behavioral hypersenstitivity are established by 4 h after injection and last through at least 96 h [1, 20, 25].

To confirm that carageenan injections were accompanied by increased sensitivity in this study, behavioral testing was performed 24 h before and 24 h and 72 h after injections. A difference between this study and others is the use of ovariectomized rats. Female reproductive hormones can modulate and alter carrageenan-induced sensitivity [32], which can present a confounding variable in intact cycling animals. In the present study we circumvented this issue by using female rats who received short-term ovariectomies, a procedure that essentially eliminates variations in ovarian hormone levels. We found that carageenan injection produces substantial increases in both thermal and mechanical sensitivity at 24 and 72h, a finding consistent with earlier reports in intact rats [17, 31]. This confirms that relatively stable and persistent thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity is elicited in this model.

A central question we wished to address was whether inflammation alone is sufficient to induce hyperinnervation. Hyperinnervation accompanies many painful inflammatory conditions, as revealed in tissue biopsies and in cadaveric specimens. However inflammation in these conditions generally does not occur in isolation but rather as a secondary feature induced by extensive tissue damage, rejection, or primary bacterial or viral infections. In the present study, we show that within 72h of inflammatory challenge, the epithelial tissue compartment shows marked increases in numbers of nerve fibers. It is noteworthy that our neuronal marker, PGP9.5, labels all intact axons and its expression levels typically do not change in conditions short of degeneration [36]. Immunostained axons are likely to reflect both the abundant non-peptidergic and less abundant peptidergic sensory fibers that populate the rodent epidermis [26]. The finding that numbers of cutaneous sensory axons are increased by injection of carrageenan but not saline argues that axon proliferation occurs as a result of the inflammatory process rather than simply physical trauma. Thus, inflammation in the absence of typically related factors (e.g., injury, infection) appears to be sufficient to induce cutaneous hyperinnervation.

It is unclear whether this increased sensory axon density contributes to the increased mechanical and thermal sensitivity we observed, but several lines of evidence suggest that it may. There is evidence that actively growing axons show greater excitability than do quiescent axons [15, 18]. Similarly, neurons with more complex geometries, as occurs following axon sprouting, also show greater excitability [19]. In the case of neurons projecting to the site of inflammation, axons are exposed to a variety of excitatory molecules including prostaglandin E2 [16], adenosine [21] and NGF [3], and greater axonal branching is likely to result in greater summation of depolarizing potentials evoked by these local factors. Branching is also likely to give rise to greater numbers of locally activated neuropeptide-releasing sites, further contributing to the inflammatory process. Accordingly, it is quite possible that hyperinnervation acts in concert with other factors, such as changes in sodium channel expression and excitability [4], to increase pain sensitivity under conditions of inflammation. Indeed, the increased mechanical sensitivity seen in the paw contralateral to the carrageenan injection is consistent with sensitization occurring centrally or as a result of systemic peripheral factors.

Findings of the present study support the idea that sensory axons respond to inflammation by sprouting new branches to increase tissue innervation density. As noted, this is now believed to be a feature common to many pain syndromes in humans. It remains unclear as to the extent to which hyperinnervation may contribute to sustaining chronic pain after acute inflammation subsides. However, in cases of provoked vulvodynia (vulvar vestibulitis) characterized by proliferation of vestibular sensory axons [5, 6, 34], excision of the tissue containing the abundant fibers provides pain relief in up to 80% of the cases [7, 13]. While this procedure does more than simply eliminate numbers of peripheral axons, it is consistent with the idea that hyperinnervation is a contributing factor in some chronically painful conditions. Additional studies are required to determine whether hyperinnervation persists following resolution of inflammation and how well this correlates with changes in sensitivity.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Michelle Winter for assistance with the rat behavioral assays. Funding for this work was provided by NIH RO1HD049615 with core support from NICHD P30HD002528.

References

- 1.Aley KO, Messing RO, Mochly-Rosen D, Levine JD. Chronic hypersensitivity for inflammatory nociceptor sensitization mediated by the epsilon isozyme of protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4680–4685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04680.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfredson H, Ohberg L, Forsgren S. Is vasculo-neural ingrowth the cause of pain in chronic Achilles tendinosis? An investigation using ultrasonography and colour Doppler, immunohistochemistry, and diagnostic injections. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003;11:334–338. doi: 10.1007/s00167-003-0391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann R, Schuligoi R. Inhibition of carrageenan-induced edema by indomethacin or sodium salicylate does not prevent the increase of nerve growth factorin the rat hind paw. Neurosci Lett. 2000;278:173–176. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00931-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black JA, Liu S, Tanaka M, Cummins TR, Waxman SG. Changes in the expression of tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels within dorsal root ganglia neurons in inflammatory pain. Pain. 2004;108:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohm-Starke N, Hilliges M, Falconer C, Rylander E. Increased intraepithelial innervation in women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;46:256–260. doi: 10.1159/000010045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohm-Starke N, Hilliges M, Falconer C, Rylander E. Neurochemical characterization of the vestibular nerves in women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1999;48:270–275. doi: 10.1159/000010198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohm-Starke N, Rylander E. Surgery for localized, provoked vestibulodynia: a long-term follow-up study. J ReprodMed. 2008;53:83–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown MF, Hukkanen MV, McCarthy ID, Redfern DR, Batten JJ, Crock HV, Hughes SP, Polak JM. Sensory and sympathetic innervation of the vertebral endplate in patients with degenerative disc disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:147–153. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b1.6814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craft RM. Modulation of pain by estrogens. Pain. 2007;132(Suppl 1):S3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Sebastiano P, Fink T, Weihe E, Friess H, Beger HG, Buchler M. Changes of protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5) immunoreactive nerves in inflamed appendix. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:366–372. doi: 10.1007/BF02065423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dib-Hajj SD, Fjell J, Cummins TR, Zheng Z, Fried K, LaMotte R, Black JA, Waxman SG. Plasticity of sodium channel expression in DRG neurons in the chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 1999;83:591–600. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Cosamalon J, Del Valle ME, Calavia MG, Garcia-Suarez O, Lopez-Muniz A, Otero J, Vega JA. Intervertebral disc, sensory nerves and neurotrophins: who is who in discogenic pain? J Anat. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaunt G, Good A, Stanhope CR. Vestibulectomy for vulvar vestibulitis. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:591–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gopinath P, Wan E, Holdcroft A, Facer P, Davis JB, Smith GD, Bountra C, Anand P. Increased capsaicin receptor TRPV1 in skin nerve fibres and related vanilloid receptors TRPV3 and TRPV4 in keratinocytes in human breast pain. BMC Womens Health. 2005;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossmann L, Gorodetskaya N, Teliban A, Baron R, Janig W. Cutaneous afferent C-fibers regenerating along the distal nerve stump after crush lesion show two types of cold sensitivity. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:682–690. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guay J, Bateman K, Gordon R, Mancini J, Riendeau D. Carrageenan-induced paw edema in rat elicits a predominant prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) response in the central nervous system associated with the induction of microsomal PGE2 synthase-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24866–24872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janig W, Grossmann L, Gorodetskaya N. Mechano-and thermosensitivity of regenerating cutaneous afferent nerve fibers. Exp Brain Res. 2009;196:101–114. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1673-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janse C, Peretz B, van der Roest M, Dubelaar EJ. Excitability and branching of neuroendocrine cells during reproductive senescence. Neurobiol Aging. 1999;20:675–683. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kayser V, Guilbaud G. Local and remote modifications of nociceptive sensitivity during carrageenin-induced inflammation in the rat. Pain. 1987;28:99–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li L, Hao JX, Fredholm BB, Schulte G, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Xu XJ. Peripheral adenosine A(2A) receptors are involved in carrageenan-induced mechanical hyperalgesia in mice. Neuroscience. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchand F, Perretti M, McMahon SB. Role of the immune system in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:521–532. doi: 10.1038/nrn1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McMahon S, Koltzenburg M. The changing role of primary afferent neurones in pain. Pain. 1990;43:269–272. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller RJ, Jung H, Bhangoo SK, White FA. Cytokine and chemokine regulation of sensory neuron function. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009:417–449. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-79090-7_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris CJ. Carrageenan-induced paw edema in the rat and mouse. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;225:115–121. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-374-7:115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rice FL, Albers KM, Davis BM, Silos-Santiago I, Wilkinson GA, LeMaster AM, Ernfors P, Smeyne RJ, Aldskogius H, Phillips HS, Barbacid M, DeChiara TM, Yancopoulos GD, Dunne CE, Fundin BT. Differential dependency of unmyelinated and A delta epidermal and upper dermal innervation on neurotrophins, trk receptors, and p75LNGFR. Dev Biol. 1998;198:57–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riley JL, 3rd, Robinson ME, Wise EA, Price DD. A meta-analytic review of pain perception across the menstrual cycle. Pain. 1999;81:225–235. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchis-Alfonso V, Rosello-Sastre E. Immunohistochemical analysis for neural markers of the lateral retinaculum in patients with isolated symptomatic patellofemoral malalignment. A neuroanatomic basis for anterior knee pain in the active young patient. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:725–731. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280051801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchis-Alfonso V, Rosello-Sastre E, Monteagudo-Castro C, Esquerdo J. Quantitative analysis of nerve changes in the lateral retinaculum in patients with isolated symptomatic patellofemoral malalignment. A preliminary study. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:703–709. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260051701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schubert TE, Weidler C, Lerch K, Hofstadter F, Straub RH. Achilles tendinosis is associated with sprouting of substance P positive nerve fibres. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1083–1086. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.029876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tabo E, Eisele JH, Jr, Carstens E. Force of limb withdrawals elicited by graded noxious heat compared with other behavioral measures of carrageenan-induced hyperalgesia and allodynia. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;81:139–149. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tall JM, Crisp T. Effects of gender and gonadal hormones on nociceptive responses to intraplantar carrageenan in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2004;354:239–241. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.09.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Treede RD, Meyer RA, Raja SN, Campbell JN. Peripheral and central mechanisms of cutaneous hyperalgesia. Prog Neurobiol. 1992;38:397–421. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90027-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tympanidis P, Terenghi G, Dowd P. Increased innervation of the vulval vestibule in patients with vulvodynia. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1021–1027. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang G, Tokushige N, Russell P, Dubinovsky S, Markham R, Fraser IS. Hyperinnervation in intestinal deep infiltrating endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:713–719. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkinson KD, Lee KM, Deshpande S, Duerksen-Hughes P, Boss JM, Pohl J. The neuron-specific protein PGP 9.5 is a ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase. Science. 1989;246:670–673. doi: 10.1126/science.2530630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winter CA, Risley EA, Nuss GW. Carrageenin-induced edema in hind paw of the rat as an assay for antiiflammatory drugs. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1962;111:544–547. doi: 10.3181/00379727-111-27849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woolf CJ. Generation of acute pain: central mechanisms. Br Med Bull. 1991;47:523–533. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woolf CJ, Ma Q. Nociceptors--noxious stimulus detectors. Neuron. 2007;55:353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woolf CJ, Thompson SW. The induction and maintenance of central sensitization is dependent on N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor activation; implications for the treatment of post-injury pain hypersensitivity states. Pain. 1991;44:293–299. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90100-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zimmermann M, Herdegen T. Plasticity of the nervous system at the systematic, cellular and molecular levels: a mechanism of chronic pain and hyperalgesia. Prog Brain Res. 1996;110:233–259. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62578-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]