Abstract

This paper provides an overview of theory in religion, aging, and health. It offers both a primer on theory and a roadmap for researchers. Four “tenses” of theory are described—distinct ways that theory comes into play in this field: grand theory, mid-range theory, use of theoretical models, and positing of constructs which mediate or moderate putative religious effects. Examples are given of both explicit and implicit uses of theory. Sources of theory for this field are then identified, emphasizing perspectives of sociologists and psychologists, and discussion is given to limitations of theory. Finally, reflections are offered as to why theory matters.

Keywords: religion, spirituality, aging, health, theory

All empirical research is theoretically based, whether explicitly or implicitly. Even in situations characterized by relatively simple and straightforward analyses, a theoretical perspective is nonetheless always present and underlies the statistical manipulation, acknowledged or not. In Wallace’s (1969, pp. vii–viii) famous introduction to the uses of theory in the social sciences, he explained:

[I]t does not seem to be the case that some sociological studies thoroughly implicate theory, while others are “atheoretical” and do not implicate theory at all; rather, all studies implicate theory, only some pay more deliberate, explicit, and formal attention to it while others pay more casual, implicit, informal attention. Theory, indeed, seems inescapable in sociology, as in every science.

As a whole, the field of empirical research on religion, aging, and health has suffered from several problems, including a lack of conceptual focus and limited familiarity with the real-world context of the phenomena of religion, of aging, and of health. Each investigator nonetheless operates from a particular theoretical position which is informed by a mid-range theoretical perspective. These theoretical perspectives in turn are derived from respective grand-theoretical orientations and, further, dictate implicit operational or analytical models. The oft-stated criticism of this, or any other, literature as largely atheoretical, as Wallace notes, does not mean that existing work is uninformed by theory. Rather, it indicates that the theoretical perspectives underlying this work are rarely acknowledged and that explicit theoretical models are not tested.

The emerging field of research at the intersection of religion and aging, especially work involving health and well-being outcomes, is at a crossroads. Estimates of the number of published articles and chapters on this topic range as high as over a thousand (see Koenig 2008). This body of evidence verifies that dimensions of religious participation are associated with positive psychosocial and health-related outcomes in older adults and throughout the life course. What is now needed is a greater effort to address the simple question, “But what does this mean?” It is time to begin paying as much attention to the how and why of this subject as to the what. Accordingly, this paper offers a primer on theory for the larger religious gerontology research field, and also something of a roadmap. The end result, it is hoped, is a convincing statement as to why theory matters for this field, as well as a summary of both the contributions of theory up to this point and the promise of theory for the future of the field.

First, an overview is provided of the scope of research findings on this subject. Several good literature reviews already exist, so this overview is concise rather than comprehensive and focuses on the breadth of research rather than the details of findings. Second, discussion is provided of what are termed the four “tenses” of theory—the four distinct ways that theory comes into play in social research, in general, and in this field, in particular. Examples are also given of both explicit and implicit uses of theory in religion, aging, and health research. Third, sources of theory for this field are described. These include perspectives of sociologists and psychologists of religion, especially those who have studied the health of aging and aged populations. In addition, some thought is given to the potential limitations of theory. One may become so wrapped up with theorizing or testing arcane theories that one loses focus on what really matters—crafting studies that produce results that add significantly to knowledge. Fourth, reflections are offered as to why this issue is so critical for this field. This includes discussion of the consequences of ignoring theory and the benefits of renewing efforts to base analyses and research programs on formal and creative theoretical frameworks.

Research and Methods in Religion, Aging, and Health

Over the past 20 years or so, numerous published reviews have summarized trends in empirical findings linking religious variables to psychosocial and health-related outcomes in gerontological and geriatric research. This body of work includes research on the effects of religious participation involving studies of older adults, longitudinal or comparative studies of older-age cohorts, studies of the dynamics of life course trajectories and age related change, and studies in which age is controlled for in analyses. All of these types of studies, taken together, can be said to constitute aging research, and the effects of religious participation have been explored through each of these approaches. Specialized and systematic reviews of religion have focused on clinical and geriatric research (Koenig 1995), studies within mainline gerontology (Levin 1997), and research exploring population-based health (Koenig et al. 2001) and mental health outcomes (Levin and Chatters 1998b). A useful distinction for categorizing these studies is between social and behavioral research, on the one hand, and clinical and epidemiologic research, on the other.

Gerontologists have utilized social and behavioral research methods to study the influence of numerous religious indicators on even more numerous measures of psychosocial constructs, physical and mental health, and general well-being. This research dates back to the early 1950s (see Levin and Chatters 2008), when Moberg first began investigating the impact of dimensions of religious participation on measures of personal adjustment (e.g., Moberg 1953). Gerontologists and geriatricians also have utilized clinical and epidemiologic methods to investigate religious indicators as putative protective (or risk) factors—that is, as exhibiting primary- or secondary-preventive effects on rates of morbidity, mortality, and disability. This research within the aging field is of more recent vintage, dating for the most part to the 1980s (see Levin and Chatters 2008). These studies are highlighted by the geropsychiatric and clinical epidemiologic studies of Koenig and associates at Duke University (see Koenig 1999) and by prospective studies pointing to significant protective effects of religious participation on longevity (e.g., Strawbridge et al. 1997) and physical functioning (e.g., Idler and Kasl 1997). The overall trend for all of these types of studies, of both categories, was recently summarized:

Higher levels of religious involvement (e.g., attendance at religious services) exhibit salutary associations with numerous medical and psychiatric outcomes: self-ratings of health, functional disability, survival rates, hypertension and cancer prevalence, smoking and drinking behavior, and most dimensions of psychological distress and well-being. Moreover, findings have emerged regardless of the race, gender, social class, age, or religious affiliation of study subjects (Levin et al. 2006, p. 1168).

Methodologically, this literature is as sophisticated as for any area of study in social gerontology, especially with respect to (a) epidemiologic investigations of religious effects on mortality/longevity/survival (e.g., Hill et al. 2005; Hummer et al. 1999; Koenig et al. 1999; Krause 2006a; Musick et al. 2004), (b) minority-aging and race-comparative studies of patterns and outcomes of religious participation throughout the life course (e.g., Ellison et al. 2008; Musick et al. 1998; Taylor et al. 2007), (c) structural models of religious correlates and predictors of psychosocial and health-related outcomes (e.g., Krause 2002b, 2004b; Levin and Chatters 1998a; Levin et al. 1995), and (d) geropsychiatric research on the salutary impact of religion and religious coping (e.g., Koenig 2007; Pargament et al. 2004).

Collectively, researchers have done a solid job at the “what” of religion and aging research. However, other questions about the religion-health connection remain only partially addressed. Over a decade ago, Krause (1997, p. S291) lamented that, despite the prodigious number of studies on this topic, still “we do not have a well-developed and intuitively pleasing sense of why these relationships exist.” This is the central issue addressed by theory, and Krause’s comment remains valid today. This is not to say that existing research has never touched on theoretical concerns. All of the research just described is informed by theory. Some of this work is informed by theory in an explicit sense, in that it references theoretical perspectives for purposes of formulating study questions and hypotheses. Other efforts are informed by theory in an implicit sense, in that studies are driven by theory-based expectations but analyses are not necessarily framed to test specific theories. The former is more typical of basic research, the latter more typical of applied research. This distinction between what we are terming explicit and implicit uses of theory has important implications for the religion, aging, and health field and will be explored more later. But, first, let us take a look at what is meant by “theory.”

Four Tenses of Theory

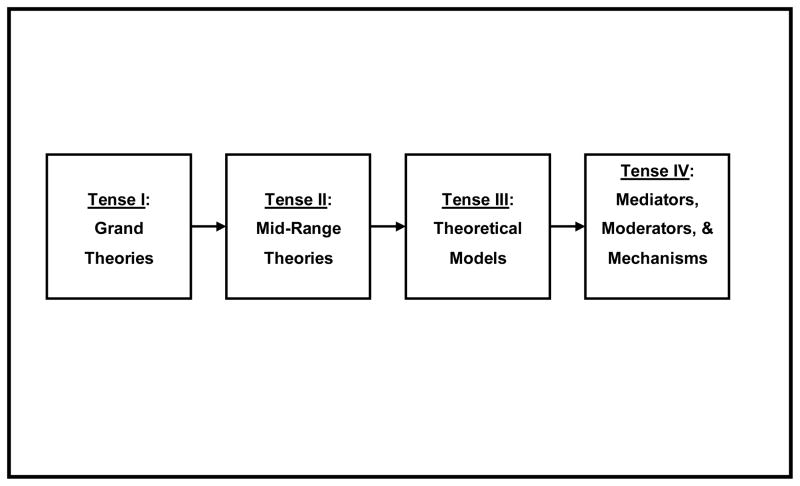

When social scientists speak of theory, there are really four different theoretical constructions that they may be referencing. These might be thought of as distinct “tenses,” if you will—uniquely inflected forms of theory arrayed along a kind of quasi-temporal line, roughly analogous to the grammatical tenses. The concept of tenses has been invoked before in gerontology, in Glass’s (1998) essay on conjugating the tenses of functional health. While too much should not be read into this metaphor, still, it is a useful way to understand the differences and relations among these four types of theory. This hierarchy of the tenses of theory is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The four tenses of theory

The first tense of theory is what sociologists refer to as grand theories. These are just what the name implies: theories with a capital “T,” “large metatheories of everything,” or “paradigmatic statement[s] reflecting a larger worldview” (Levin 2007, p. 202). Within sociology, historically, three such meta-theoretical orientations have been recognized. These are the functional, structural or conflict, and symbolic interactionist schools, taking their cues from Durkheim, Marx, and Weber, respectively. Within psychology, the phrase grand theory is not used, but the concept of schools or “forces” has great currency. Two such schools have been dominant over the past century: the psychodynamic or psychoanalytic and the behaviorist schools, taking their cues, more or less, from Freud and his followers and Watson and Skinner and their associates, respectively. In the past few decades, third and fourth forces have been acknowledged, namely the humanistic and transpersonal schools of Maslow and Rogers and of Tart and others, respectively.

The second tense of theory is that of the myriad theoretical perspectives seeking to explain particular social, psychological, and behavioral phenomena. Unlike grand theories, these are “less-reaching theories specific to particular fields or issues” (Levin 2007, p. 202). While such perspectives grow out of grand-theoretical orientations, this is not always explicitly acknowledged. Within sociology, these are referred to as “theories of the middle range,” the name preferred by Merton (1967). Famous mid-range theories in sociology include relative deprivation, the self-fulfilling prophecy, cognitive dissonance, social mobility, and the anomic antecedents of suicide. Mid-range theories referenced in social gerontology are legion and include disengagement theory, activity theory, and attachment theory, among others. An early review of the religion, aging, and health literature identified half a dozen such perspectives as implicit in existing research studies (Levin 1988).

The third tense of theory includes posited theoretical models, from which emerge the hypotheses and expectations that underlie research endeavors. Theoretical models derive from respective mid-range theories, which is quite a bit more likely to be acknowledged than the origin of respective mid-range theories in grand theory. These models, in turn, inform the construction of operational models that guide and define empirical analyses. Examples of the latter include the myriad structural-equation, or path, models that posit associations among concepts, found in all substantive areas of social science research. In the religion and aging field, several such theoretical models have been identified. These competing configurations of the interrelationships among religion, physical and mental health, and associated mediating factors have been termed the suppressor model, the distress-deterrent model, the prevention model, the moderator model, and the health effects model (see Koenig and Futterman 1995; Krause and Tran 1989; Levin and Chatters 1998b). This taxonomy owes much to Wheaton’s (1985) earlier classification of theoretical models of coping in the stress literature.

The fourth tense of theory includes those mediators, moderators, and mechanisms that ostensibly explain empirically observed relations among respective independent and dependent constructs. The postulation of such variables is a key component of theoretical and thus operational models. It is especially important, in this context, to differentiate among a few distinct concepts that are often wrongly used interchangeably. A mediator is a variable that occurs intermediate to respective independent and dependent variables in a presumed causal pathway. By contrast, a moderator is a variable that interacts with a presumed causal association between two other variables, often by anteceding it. In the language of epidemiology, the latter is also known as an effect-modifier, and its operation is typically observed by stratifying the presumed causal association separately by categories of the moderator (Last 1995). The term mechanism is also occasionally used, referring to a construct or set of variables that explains a presumed causal association between two other variables. To be clear, “explain” here does not imply “explain away” (see Pargament 2002)—more like “account for” —and can include mediating, moderating, or effect-modifying functions.

For the religion and aging field, several researchers have efforted to identify and classify the various mechanisms or categories of mechanisms that may be posited to explain putative associations between religious indicators and health-related and psychosocial outcomes. The pertinent issue here is to identify those characteristics, functions, expressions, or manifestations of religious participation that are or should be salutary. Investigators, collectively, have identified numerous such features of religious identity and practice that have been shown to, or are believed to, impact on human well-being, among older adults especially. These exert their effects, in part, through a variety of proposed behavioral, psychosocial, interpersonal, cognitive, affective, conative, psychodynamic, psychophysiological, and biological pathways (see Ellison 1994; Ellison and Levin 1998; Idler 1987; Levin 1996; George et al. 2002).

The important lesson regarding theory, in the context of research on religion, aging, and health and elsewhere, is this: each of these tenses of theory comes into play in how questions are posed, how hypotheses are framed, how studies are designed, how analyses are run, and how results are interpreted. Moreover, this is so whether a respective investigator is consciously aware of these theoretical underpinnings or not.

Explicit and Implicit Uses of Theory

A related issue to consider here is whether theory is invoked explicitly or implicitly (see Bengtson et al. 2005). This is in reference to the use of theory in constructing study aims and questions, framing hypotheses, specifying models, conducting analyses, and interpreting results. Explicit uses of theory are those in which theoretical perspectives are overtly acknowledged and are formally drawn upon in the conduct of the research process—i.e., those steps listed in the previous sentence. Implicit uses of theory are those in which theory is more covert, one might say, and not as openly or explicitly referenced in interpretations of the results of research. This may be because theory was not drawn upon in any formal sense, or, alternatively, because, though referenced, theoretical issues necessarily have taken a back seat to discussion of more pressing clinical or other applied considerations.

What is being referred to as an implicit use of theory does not in any way imply that the investigator is unaware of the importance of theory or is guilty of ignoring theory. Rather, by implicit is meant simply that the analysis in question is not formally set up as a test of a theory or set of theory-based hypotheses. The research is thus not explicitly theory-driven. But it nonetheless may examine a set of propositions or expectations based on theory or prior observations. In some academic disciplines and fields, notably the clinical fields, formal theory-testing is simply not the norm. Referring to a particular application of theory as implicit should not be taken as criticism, but rather as a descriptor of a stylistic preference in writing a scholarly paper. But, this does not mean that the research is atheoretical. Stating that a use of theory is implicit is not at all to be taken as a criticism—just as a descriptor of a stylistic approach in scholarly writing. For clinical manuscripts, especially, proving or disproving a theory is not as often the main concern as in academic social science studies. Applied research, by definition, and this includes clinical research, is more focused on evaluating responses to immediately presenting problems and issues, and less on investigating purely theoretical concerns.

The religious gerontology research literature has many good examples of explicit uses of theory. Work by Neal Krause is characterized by explicit, overt references to theory. His studies on religion and health in older age explicitly craft theoretical analyses. Further, his findings provide meaningful information that leads to modifications of theoretical expectations for explicit use in constructing subsequent investigations. Notable examples include investigations of competing model specifications for the religion-stress relationship in older African Americans (Krause and Tran 1989), common and unique facets of religion as predictive of well-being in older African Americans (Krause 2004b), racial differences in church support and connectedness to God as determinants of health in older adults (Krause 2002b), stress-buffering effects of church support on health in older adults (Krause 2006b), the nonlinear relationship between religiosity and self-esteem in older adults (Krause 1995), and racial differences in how religious meaning impacts well-being in older adults (Krause 2003). Throughout, Krause provides detailed reference to the mid-range theoretical foundations of his analyses, proposes alternative theoretical models to be tested, specifies a variety of mediating or effect-modifying variables, and conducts sophisticated multivariable or multivariate analyses, often using covariance structure modeling techniques. All of these studies were published in the prestigious Journal of Gerontology and, as a body of work, they reflect a masterful use of theory. Other especially creative examples of explicitly theory-driven research on religion and aging can be found throughout the work of Ellison (e.g., Ellison et al. 2001), Pargament (e.g., Pargament et al. 2001), Ferraro (e.g., Ferraro et al. 2000), and Idler (e.g., Idler et al. 2001).

In the religion, aging, and health field, one may also find many nice implicit uses of theory. When speaking of clinical studies, the word theory should not be taken to mean what it does in the social science sense, but more akin to the sum of clinical expectations, which is functionally equivalent for these studies. The most notable example is Koenig’s model of religion’s influence on the known risk factors for cases of affective disorders—essentially an etiologic “map” of these diagnoses (Koenig et al. 1997). More or less a gigantic path model, Koenig and his associates connect almost 20 different classes of risk factors with the outcome and with each other. Included in this model are health behaviors, alcohol and drugs, medications, genetic factors, personality, physical illness, brain disease, comorbid psychiatric illness, stressful events, aging changes, chronic pain, disability, cognitive appraisal, social support, economic resources, coping behavior, altruistic activities, and a history of prior depression. The model also indicates each construct and relationship for which religious correlates have been validated or hypothesized. This model has served as a template for the comprehensive program of empirical research on religion and mental health undertaken by Koenig and his associates at Duke University (see Koenig 1999).

As these are mostly clinical studies, this etiologic map is not organized as a narrative theory nor utilized as a source of explicitly tested hypotheses. This formulation of the putative role of religion in mental health is nonetheless remarkably theory-based in its content and purpose. The ultimate foundation of such “theory” is not grand theory, as in Durkheim and Weber, but instead the pathophysiological principles of biomedicine, as currently understood, coupled with current psychiatric-epidemiologic observation. This is a perfectly reasonable and acceptable theoretical basis for this research. Other exemplary and creative uses of theory in such an implicit fashion can be found throughout the research of several psychologists of aging, notably Ai et al. (2002). This work exemplifies research which is constructed around the examination of relationships among theory-informed conceptual models, but which does not necessarily seek to validate an explicitly postulated theoretical model or mid-range theory (although, in actuality, its results may serve to do just that). To reiterate, while not explicitly theory-based in the same way that social scientists might conceive of it, nonetheless such work is carefully framed and guided by a theoretical understanding and by theoretical expectations.

An important caveat: we do not wish to imply that only sociological research in this field is explicitly theoretical while all psychological and psychiatric research is implicitly theoretical. Explicitly theoretical work on religion and aging has come from psychologists, such as Pargament (see Pargament 1997); McCullough, who conducted a test of rational choice theory as an explanation for trajectories of religious development throughout the life course (McCullough et al. 2005); and McFadden, whose body of research and writing over many years has served as a theory-rich exploration of religion and personality throughout the life course (e.g., McFadden 1999). Indeed, McFadden is blunt in her assessment of the importance of explicit theory for the psychology of aging when she states, “Research on religion, personality, and aging should be theoretically based, testing mid-range theories” (McFadden 1999, p. 1099). Theories of religious coping and attachment, according to McFadden, are good places to begin.

Needless to say, not all gerontological research on religion in which theory is implicit, rather than explicit, is as fully realized as in these examples. That attests to the care with which these investigators have approached their craft. However, the same cannot be said across the board. There is a large body of published research where theory simply has been ignored. Navigating these issues is “both intellectually and methodologically challenging” (George et al. 2002, p. 199), to be sure, which serves to deter deep engagement of the topic in favor of superficial ventures in number-crunching. But this is no excuse. Sources of theory do exist, though underutilized, and constitute a rich vein for gerontologists to tap in exploring religious phenomena.

Sources of Theory for Religion, Aging, and Health

Anyone searching for sources of theory for this field does not have far to look. Besides the various articles already cited, there are existing literature reviews, handbook and encyclopedia entries, and book chapters, some of recent vintage, that make very good places to begin (see Ellison 1994; Idler 2006; Krause 2006c; Levin 2006; McFadden 1996a, b; McFadden and Levin 1996; Moberg 1990). Several recent books on topics related to religion and aging also contain lengthy and detailed material addressing theory (e.g., Krause 2008; Pargament 1997; Taylor et al. 2004). Finally, anyone venturing into this field would do well do examine the dozens of chapters contained in the two volumes of Aging, Spirituality, and Religion: A Handbook, published several years ago (Kimble and McFadden 2003; Kimble et al. 1995).

Any serious consideration of theory, however, must extend deeper than perusal of reviews of applications of theory to the religion, aging, and health field. The roots of this work lie in the scholarly research and writing of experts in religious studies, mostly social and behavioral scientists, who have been conducting sophisticated and empirically based conceptual and theoretical analyses of religion for about half a century. Unfamiliarity by novice researchers with these long-standing fields of study in the social sciences no doubt has contributed to the neglect of theory in religion and aging research.

The conceptualization and measurement of religious constructs have been important issues in sociology and social psychology since the late 1950s. Researchers have come to recognize that religion is a complex and multidimensional domain of human life comprising behaviors, attitudes, beliefs, emotions, thoughts, experiences, and values. Accordingly, well over a hundred lengthy measures have been developed and validated (Hill and Hood 1999). Most work in the sociology of religion derives from Glock and Stark (1965) and others who have sought to outline these multiple dimensions of religious participation and commitment. Measurement instruments in this tradition consist of subscales of four, five, and even 11 distinct dimensions (e.g., religious devotion, affiliation, ideology, experience). Within the psychology of religion, a parallel conceptual tradition has developed. Based on Allport’s (1979) distinction between “institutionalized” and “interiorized” religion, existing instruments in this tradition seek to differentiate between respective “extrinsic” and “intrinsic” motivations for religious expression.

Despite this work by both sociologists and psychologists of religion, the development of numerous scales and indices has not led to their widespread adoption by researchers in other disciplines whose studies often require collection of data on religion, such as gerontology. To be fair, among researchers in health-related disciplines, gerontologists have done better than others (e.g., epidemiologists, physicians) in one respect. A systematic review found that over half of published empirical studies on religion and aging used multiple measures of religiousness (Levin 1997). This is in contrast to other fields that embrace the flawed practice of analyzing a single religious variable (typically religious service attendance or affiliation) and then generalizing the results to all of “religion.” Still, such usages do not mean that these measures are utilized for the testing of domain-specific theories about religion’s putative effect on health or aging-related outcomes. In spite of the existence of scores of acceptable validated measures of dimensions of religion and their use throughout the religion and aging literature, sophisticated theoretical engagement continues to languish.

This state of affairs likely results from the general unfamiliarity of most gerontologists and geriatricians with the history and substance of scholarship in the sociology and psychology of religion. However, another important explanation is the recognized inconsistencies between existing measures of religion and the specific needs of aging and health researchers. To the point, according to one review, “of the recent advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religious involvement, few have addressed those religious dimensions that bear the closest theoretical relationship to health (e.g., religious support, coping, and meaning)” (Ellison and Levin 1998, p. 710). Efforts have been made to remedy this, notably through the work of the NIH Workgroup on Measures of Religiousness and Spirituality, convened in the late 1990s to begin addressing these deficiencies (see Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group 1999; Idler et al. 2003), and others (e.g., Chatters et al. 2001; Krause 2002a). While there is some evidence of subsequent improvement (see Levin and Chatters 2008), whether we are truly on the cusp of a new era of more theory-driven research remains to be seen.

A related issue concerns the all too common confounding of the terms “theoretical” and “conceptual,” a source of considerable confusion not only in this field but in the social sciences as a whole. Although these two words are often used interchangeably, they do not mean the same thing. Conceptual refers to issues regarding the definition and assessment of the ideas, abstractions, or principles involved in the constructs whose relations are investigated in a study. By contrast, theoretical refers to the postulating of theories that ostensibly govern the relations among respective constructs. Deciding upon which dimensions of religiousness, or health status, one will measure, then selecting or devising such measures and, where necessary, validating them is a conceptual task. Positing these constructs in a structural model, along with any requisite mediating or moderating variables, and concomitantly reasoning through the underlying basis for such a specification is a theoretical task. Clearly, these are different tasks.

More than just a semantic issue, these differences have implications for how research questions and hypotheses are constructed, how research is conducted, and how results are interpreted. Some investigators attend to conceptual issues (i.e., definition and assessment), but then fail to relate this process to the larger theoretical context of their research. Different dimensions of religious participation can be expected to exhibit different effects on different outcomes and for different reasons (see, e.g., Levin 1996). These ideas and connections need to be drawn out and reasoned through, with reference to existing theories, past research, and, where applicable, clinical observations. Decision-making regarding the use of respective constructs is important, but can only meaningfully occur in a theoretical context. Otherwise, how do we decide what constructs to select, how do we know what to expect to find in our analyses, and how do we begin to understand our results?

An interesting question to think about in reasoning through the research process, then, is which must come first—the conceptual or the theoretical? A case could be made that engaging the conceptual must precede engaging the theoretical, in that the construction of theoretical models must be anteceded by the reasoned selection of inclusive constructs. On the other hand, this suggests that conceptual thinking must itself be informed by theoretical thinking. So, theory is important from the beginning, even before conceptual issues are engaged. Perhaps this is a chicken-versus-egg issue that is unresolvable. Regardless, it underscores the ubiquity of theory’s role in the research process. The savvy investigator must be theoretically astute—or at least inquisitive—from the beginning, even if the positing of formal hypotheses is not an immediate concern.

A Primer on Using Theory

How, then, should one proceed? In making use of theory in research on religion, aging, and health, several steps can be envisioned. These are not original; they are the familiar stages of the research process for social and population-health researchers. At each stage, theory comes into play, or should come into play. At some point in this process, all of the tenses of theory have their say. The end result, ideally, is a research study that systematically builds on prior knowledge and provides new results that serve to advance our understanding of the role of religion in aging and health.

-

Theory is necessary in order to formulate research questions. In order to determine what issue(s) to investigate, one must have a sense of what has been done already and also what is possible or likely in light of current theoretical understandings. Although the religion, aging, and health field has a wealth of empirical findings, some issues have been left unexamined. There are respective disease outcomes, especially in epidemiologic context, that have not been examined yet. There is also very little in the way of explorations of dimensions of religious expression outside of a few familiar measures of public religious participation (see Levin 2003). Further, despite the volumes of published findings, there have been relatively few appropriately specified structural models. The careful work of researchers like Krause is more the exception than the rule. We still do not really have a good understanding of the complexity of the intervening variables that link religious indicators to measures of psychological functioning and physical and psychological wellbeing.

The most pressing need therefore is for well thought out theoretical models that specify which religious dimensions impact on which outcomes and through which intervening or explanatory mechanisms. This requires a fluency in the various mid-range perspectives that have been proposed for respective subject areas. It also requires at least a grasp of the meta-theoretical issues implicit in the sociological grand theories or the principles of the psychological schools that underlie such mid-range perspectives. Of course, no one designs a study to test a grand theory, at least not in the past half century, but a decent sense of the implicit theoretical foundations and implications of how one specifies a set of construct relationships would provide for more thoughtful studies that can truly contribute to knowledge.

A corollary to this point is that theory is necessary in order to select constructs and measures to be used in a particular study or analysis. Presumably, one has a sense of certain construct relationships that merit investigation—for example, between a particular religious dimension and a particular psychosocial and health outcome in a particular population. Also presumably, this sense derives from a combination of prior observations and the reasoned expectations of theoretical writing of some sort. Consequently, in ideal circumstances, a respective investigator either looks for secondary data sources in which such constructs are available or undertakes an original data collection in which measures of such constructs are first developed and validated. The reality, however, may be quite different. An investigator new to the field of religion, aging, and health may undertake a study with neither an appreciation of any underlying theoretical issues—or even an awareness that they exist—nor familiarity with any past research. Unfortunately, this approach can result in a publication due to the misperceived “novelty” of religious research in certain scholarly disciplines and content areas.

Theory is necessary in order to frame hypotheses. This point is obvious. In order to gauge what one might expect to observe in a subsequent analysis, one must construct hypotheses that reflect what the investigator perceives to be reality. This may be a reality constructed from a synthesis of prior theoretical writing on constituent construct relationships in one’s theoretical model. It may be a reality constructed from a summary overview of prior empirical findings. It may be a reality constructed from clinical observations or from observations of social and psychological phenomena within an applied setting. Or it may be some combination of the above. This may sound like a lot of work, but, in actuality, the very best researchers in any social or behavioral science field engage in this intellectual process as a matter of course. The background sections of their papers routinely provide a transparent look at the underlying reasoning and mental iteration that led to the formulation of their hypotheses.

-

Theory is necessary in order to design studies. The wrong design may negate the possibility of properly testing even the “right” hypotheses. At the same time, the right design can at least result in useful findings that may enable us to evaluate and pass judgment on even weakly constructed hypotheses. In addition, certain designs may be more or less useful in addressing certain issues that arise within the religion, aging, and health field and some questions may only be answerable through use of particular types of study designs.

For example, one of the earliest methodological issues to arise in religion and health research was the possibility of confounding between measures of religious service attendance and functional health among older cohorts. That is, because those older adults with substantial activity limitation or disability may less frequently attend religious services for reasons unrelated to the intrinsic strength of their religiousness, but due instead to health reasons, any positive association observed between the two measures in survey data may be suspect: it could be that poor functional health was driving infrequent religious behavior, not that frequent religious behavior was responsible for good functional health (see Levin 1988). In such an instance, prevalence (i.e., cross-sectional) study designs would be the least effective choice if one wants to tease out the relation between these constructs. These observations were first made over two decades ago, and it has since been confirmed through longitudinal research that disability does produce a barrier to religious attendance, but only contemporaneously to the functional limitation, not in the long term (see Kelley-Moore and Ferraro 2001). Older adults with modest levels of functional impairment can be quite resilient in maintaining lifelong levels of participation in congregational religious services.

To study this particular subject, the decision-making regarding study design would thus require some understanding of what is entailed in public worship, the normative frequency of such gatherings in respective faith traditions, the congregational accommodations to people with disability or other limitations, the measurement and social demography of functional health, and the limits of inferences drawn from respective study designs. Negotiating these issues requires some theoretical awareness—in this instance, related to the sociology of religion, to health status assessment, to the demography of aging, and to the calculus of what epidemiologists refer to as occurrence relations.

-

Theory is necessary in order to analyze data. Because the analysis of data always requires the specification of a model of relationships among constituent variables, no analysis can truly be said to be atheoretical. Even a simple bivariate regression, with no intervening variables, makes undeniable assumptions of a presumably causal nature (i.e., the distribution of variable Y is a direct function of the distribution of variable X). The investigator, if a novice or unsophisticated, may not be consciously aware of these presumptions, but they are nonetheless there. The remedy is to make sure that every data analysis is the result of reasoned specification of relationships, ideally based upon a consciously posited theoretical model that underlies a given research project. The methodological limitations of observational research, relative to true experiments, may also offer a theoretical advantage: the opportunity to analyze our data in the rich context provided by a postulated theoretical framework.

In specifying a set of relations among constructs, as in a structural model, we are not looking for perfection—just a reasoned effort to lay out the expected paths among major constructs. As Blalock (1982, p. 147) once noted, “It goes without saying that any explanatory model of a complex reality must inevitably be oversimplified.” Each discipline and field has its respective set of constructs deemed fair game. In seeking to understand how religion and health are related among older adults, a sociologist, for example, is unlikely to specify hormonal or immunologic mediating effects, but omitting particular psychosocial variables might in some instances lead to a misspecified or inadequate model.

Theory is necessary in order to interpret results. The results of a given set of data analyses, even where the findings are consistent and straightforward, may not be uniformly interpreted. Statistical associations that are plain to one investigator with a deep theoretical grasp of a subject may mean something entirely different to someone else. In many instances, findings from population research showing significant structural associations between a religious indicator such as frequency of formal religious participation and a measure of health status are described as having provided evidence for a “healing power” of faith or spirituality. This is despite the facts that such studies do not address therapeutic effects (but rather protective effects in well populations) and that formal religious participation, spirituality, and faith are entirely different constructs (see Levin 2009). Moreover, what is meant by “power,” a considerably confusing word in light of the many studies that show religious effects mediated or moderated by as many as half a dozen very distinctive psychosocial constructs? In some fields, such as complementary and alternative medicine, many religion and health research findings are frequently misinterpreted in this way.

More troubling are situations in which the meaning and implications of results are not effectively grasped. This is not very different from what goes on in any other substantive field. Different from other fields, the meta-construct of religion is fraught with emotional baggage for many academicians—both positive and negative. Given this, even where significant findings are reasonably interpreted, their implications may be overblown. This field has suffered from a tendency of investigators to conduct a study which will “prove,” once and for all, that religion (typically unspecified) is a salutary resource—or is not. Results of even the most meager analysis are then enlarged upon to accommodate one of these respective polarities. Presumably a research project is undertaken because there is a delimited problem to solve—or issue to resolve not as a quest to redeem or disprove an entire field.

The Limits of Theory

It is important to recognize that a sole or inordinate focus on theory can also be detrimental to the development of research. That is particularly the case when the focus on publishing new research is so much on theory that one loses an emphasis on significance. That is, the findings of the paper may be very significant even though there may not be a major theoretical contribution. This overemphasis on theoretical contribution has been a limiting factor, for example, in research on minority groups. In some instances, research on respective ethnic-minority populations is rejected for publication because the findings are similar to those from prior research conducted among Whites. In other situations, research using a minority-only sample is the first work to appear on a particular topic yet receives criticism because the respective study population was limited to a minority group. For understudied populations, fundamental descriptive information is vital to subsequent research efforts. Obtaining and presenting such information may take precedence over explicit theory-testing.

Theory is modifiable based on a body of scientific evidence. Theory represents a provisional blueprint or map for the investigation of social and behavioral phenomena. Theory-building, itself, is an ongoing and interactive process in which specific relationships are posited, tested, and evaluated by different, independent research investigators. Modifications in theory occur when they are put to the test within the community of scholars whose accumulated evidence either confirms or disconfirms specific theoretical assumptions and relationships. As a human activity, theory-building is inherently contextual and involves a community of scholars who are engaged in the construction of knowledge. As actors in this process, researchers and scholars bring with them their own values and perspectives which influence the topics that they choose to study and that shape the questions that they ask and the methods that they employ. The theory-building process embodies important “checks and balances” to research and is particularly important for understanding how “new” elements of a social reality are incorporated into theory and how limited theory is subsequently either modified or abandoned.

Although this paper has argued for the need for theory in order to advance research in the religion, aging, and health field, there are situations in which a blind allegiance to theory impedes understanding of social phenomena. Owing to the entrenchment of prevailing perspectives or paradigms within a field, theory oftentimes fails to adapt and change in the face of contradictory evidence and different social realities. This has the effect of reifying theory in ways that divergent experiences and phenomena are ignored, particularly for population groups whose experiences and life realities are marginalized. Too great an emphasis on the use of “theory for theory’s sake” brings about a situation in which “bad” or inappropriate theory is employed indiscriminately and without reference to important differences in the inherent meaning and contextual and social environment in which phenomena are manifested. Further, given the power of prevailing theoretical paradigms to shape the conversation, research agenda, and methods in a field, divergent perspectives and viewpoints, often from minority scholars, are penalized.

A case in point from the field of family studies underscores this problem. Family theory continues (often slowly) to evolve in relation to the changing demographic realities and diversities of today’s families (Bengtson et al. 2005). It is not, however, a given that this process of change will occur in a timely, systematic, or planned manner. In this field, the topic of racial and ethnic-minority families has been the site of significant ideological differences and disputes. In engaging the topic of minority families, scholars encountered broader questions related to the implicit and explicit values and assumptions that underpin theory and research and our beliefs about normative family structure and its relation to family process and functioning. In fact, significant debate surrounding these topics prompted a major reevaluation of the nature and purpose of race-comparative research, specifically in relation to African-American families (Allen 1978). In the mid to late 1970s, a number of scholars of African-American families argued that, owing to the use of a simple comparative framework, theory and research on Black families embodied a deficit perspective in which they were characterized as being deviations from White, middle-class norms.

Over the years, the field of religion, aging, and health has similarly addressed issues of racial and ethnic differences in religiosity and the role of racial and ethnic diversity in understanding the relation of religion to the aging process as well as religion’s impact on substantive outcomes such as physical and mental health. This process, while at times slow, imprecise, and cumbersome, has enriched subsequent research efforts and theory development. For example, early theory on African-American religious involvement was typically grounded in frameworks that were largely acontextual and that stressed the compensatory features of religion for this group. That is, given deprivations and blocked opportunities in other areas of life, African Americans turned to religion for solace. This perspective, in turn, led to a wholesale characterization of all African Americans as being religious and to a regrettable lack of attention to issues of within-group variability and social context or to the theoretical underpinnings that might explain these possible differences (see Taylor et al. 2004).

Theories in other fields have legitimately been criticized for hampering the development of research. The work of Gilligan (1982) in psychology is noted for her critique of the universal theories of Erickson and Kohlberg as being dominated by a male, Eurocentric, and individualist perspective. In the caregiving field, there have been critiques indicating that theories in this literature are solely based on the perspective of female caregivers and, as such, the role and contribution of male caregivers is overlooked (Kramer and Thompson 2002). The similarity to research in religious gerontology, with a half century of accumulated knowledge based primarily on samples of White North American Christians, is obvious.

More contemporary research on religion, aging, and health has given greater attention to important differences in the meaning ascribed to religion across and within distinct population groups, including African Americans. The collective efforts of several researchers have helped to build frameworks that are sensitive to the life experiences of African Americans, Hispanics, and other minority groups and which contextualize religious phenomena with respect to broader sociohistorical events, cultural factors, and community norms, characteristics, and dynamics, as well as to pertinent institutional (e.g., religious affiliation) and individual (e.g., stress, coping, personality) factors. But this process has not necessarily been a given, and there are many instances in which religious phenomena pertaining to racial, ethnic, or cultural minorities have been tortured and distorted in order to fit a particular theory.

In summary, the ongoing process of theory development for this field must involve theory-building and modification, as well as abandoning theory that is acontextual or flawed in its scope and/or capacity for understanding and explaining social reality. Similarly, rather than blind allegiance to theories that are inadequate in their scope and form—what might be termed “theory for theory’s sake”—it is critical that the limitations of weak theory be acknowledged. Further, studies indicating important new findings should not be overlooked or rejected solely due to a perceived lack of theoretical advancement.

Why This Matters

Among clinical and biomedical scientists, social and behavioral science and population based research is sometimes negatively characterized as being “descriptive” and of the same class as case studies, anecdotal evidence, and other ostensibly qualitative methods. Epidemiologic research is also typically lumped into this “descriptive” category, as well. This label, of course, reflects a basic ignorance of the diverse methodologies and epistemological traditions of these disciplines and fails to do justice to public health research and to the sophisticated labors of social and behavioral scientists and epidemiologists. Social and behavioral scientists involved in the study of religion, aging, and health are well aware of these misperceptions and biases. This field runs the risk of becoming medicalized and dominated by research agendas set by those without any background in social or population-health research methods, not to mention religious research.

More fundamentally, however, there is a lack of appreciation for the role and functions of theory in relation to scientific inquiry. For some, theory seems to be perceived as something of a luxury—a purely intellectual exercise among social scientists without any substantive importance. As has been argued here, theory at its most basic represents a description of reality. A particular theory or theoretical perspective, then, is a lens or psychic grid through which the world is viewed and understood. It is theory, more than anything else, that enables us both to make sense of our existing observations and to craft expectations as to what we will find in subsequent investigations. Theory and theorizing are imperative for respective scientific fields to advance and are essential for scientists, whether biomedical or behavioral or social. Entering into an empirical research study without first having engaged the pertinent theoretical work is like starting a journey without a map. The map is not the “reality” of the terrain, but reflects our best assumptions and is capable of modification and revision as new information is systematically tested and evaluated and shared within the community of investigators. In short, we all need to engage theory.

Several years ago, a significant effort was made to advance the thoughtful engagement of theory in the field of religion, aging, and health. The 16th Annual Penn State University Conference on Social Structure and Aging, in 2002, was convened in order to bring into focus the “why” of religion’s impact on health and well-being in older adults (Schaie 2004, p. x). In his introduction to the published proceedings, Krause (2004a, p. 4) asked, “What is the best way to approach the study of religion, aging, and health?” The answer, he concluded, is multifaceted, with greater attention to theory being front and center.

First, in addition to greater attention to the body of extant theory on religion, aging, and health, researchers should access prior research on religion, developing research questions that build on the lessons of past research and writing. Second, greater attention needs to be paid to the specific context domain of religion whose effects one intends to examine. Religion can no longer be treated as some sort of singular entity. Published research verifies that the specific measure of religion that one chooses to investigate matters and that religious dimensions cannot be viewed as essentially interchangeable. Third, detailed, multivariate models need to be posited for the proposed interrelationships among religious concepts and the outcome measures under investigation. This implies greater attention to the varied mediators, moderators, and other mechanisms that potentially link religion and, for example, health or psychological well-being in older populations. Clearly, for all three of these recommendations, “theoretical issues inevitably come to the foreground” (Krause 2004a, p. 8).

We are hopeful that investigators in the religion, aging, and health field will continue to take seriously the charge to redouble their efforts in attending to the role of theory at all stages of the research process. Programs of research in this field that are grounded in theory-based frameworks, whether explicitly or implicitly, can contribute to the continuing development of interesting new avenues of investigation. Research and writing from these programmatic efforts, in turn, can more systematically advance knowledge about the patterns, determinants, and outcomes of religious participation among older adults and throughout the life course and increase the scholarly understanding of religion’s impact on aging and health.

References

- Ai AL, Peterson C, Bolling SF, Koenig H. Private prayer and optimism in middle-aged and older patients awaiting cardiac surgery. The Gerontologist. 2002;42:70–81. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen WR. The search for applicable theories of Black family life. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1978;40:117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW. The nature of prejudice [1954] New York: Basic Books; 1979. pp. 444–457. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Acock AC, Allen KR, Dillworth-Anderson P, Klein DM. Theory and theorizing in family research: Puzzle building and puzzle solving. In: Bengtson VL, Acock AC, Allen KR, Dillworth-Anderson P, Klein DM, editors. Sourcebook of family theory and research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Blalock HM., Jr . Conceptualization and measurement in the social sciences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD. Advances in the measurement of religiosity among older African Americans: Implications for health and mental health researchers. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. 2001;7:181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG. Religion, the life stress paradigm, and the study of depression. In: Levin JS, editor. Religion in aging and health: Theoretical foundations and methodological frontiers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. pp. 78–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Boardman JD, Williams DR, Jackson JS. Religious involvement, stress, and mental health: Findings from the 1995 Detroit Area Study. Social Forces. 2001;80:215–249. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25:700–720. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Musick MA, Henderson AK. Balm in Gilead: Racism, religious involvement, and psychological distress among African-American adults. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2008;47:291–309. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro KF, Kelley-Moore JA. Religious consolation among men and women: Do health problems spur seeking. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2000;39:220–234. [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research. Kalamazoo, MI: John E. Fetzer Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Ellison CG, Larson DB. Explaining the relationships between religious involvement and health. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13:190–200. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C. In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA. Conjugating the “tenses” of function: Discordance among hypothetical, experimental, and enacted function in older adults. The Gerontologist. 1998;38:101–112. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glock CY, Stark R. Religion and society in tension. Chicago: Rand McNally; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Angel JL, Ellison CG, Angel RJ. Religious attendance and mortality: An 8-year follow-up of older Mexican Americans. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2005;60B:S102–S109. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.2.s102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Hood RW, editors. Measures of religiosity. Birmingham, AL: Religious Education Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hummer RA, Rogers RG, Nam CB, Ellison CG. Religious involvement and US adult mortality. Demography. 1999;36:273–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL. Religious involvement and the health of the elderly: Some hypotheses and an initial test. Social Forces. 1987;66:226–228. [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL. Religion and aging. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 6. San Diego: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 227–300. [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Kasl SV. Religion among disabled and nondisabled persons II: Attendance at religious services as a predictor of the course of disability. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1997;52B:S306–S316. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.6.s306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Kasl SV, Hays JC. Patterns of religious practice and belief in the last year of life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2001;56B:S326–S334. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.s326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Musick MA, Ellison CG, George LK, Krause N, Ory MG, et al. Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research: Conceptual background and findings from the 1998 General Social Survey. Research on Aging. 2003;25:327–365. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Moore JA, Ferraro KF. Functional limitations and religious service attendance in later life: Barrier and/or benefit mechanism? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2001;56B:S365–S373. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.s365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble MA, McFadden SH. Aging, spirituality, and religion: A handbook. Vol. 2. Minneapolis: Fortress Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kimble MA, McFadden SH, Ellor JW, Seeber JJ. Aging, spirituality, and religion: A handbook. Minneapolis: Fortress Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Research on religion and aging: An annotated bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. (Comp.); 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. The healing power of faith: Science explores medicine’s last great frontier. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Religion and depression in older medical inpatients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15:282–291. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000246875.93674.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Medicine, religion, and health: Where science and spirituality meet. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Blazer DG, Hocking L. Depression, anxiety and other affective disorders. In: Cassel CK, Cohen HJ, Larson EB, Meier DE, Resnick NM, Rubenstein LZ, Sorensen LB, editors. Geriatric medicine. 3. New York: Springer; 1997. pp. 949–968. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Futterman A. Religion and health outcomes: A review and synthesis of the literature. Paper presented at Methodological Approaches to the Study of Religion, Aging, and Health, National Institute on Aging; Bethesda, MD. March 16–17.1995. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Hays JC, Larson DB, George LK, Cohen HJ, McCullough ME, et al. Does religious attendance prolong survival?: A six-year follow-up study of 3,968 older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 1999;54A:M370–M376. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.7.m370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DL. Handbook of religion and health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer BJ, Thompson EH, editors. Men as caregivers: Theory, research, and service implications. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Religiosity and self-esteem among older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1995;50B:P236–P246. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.5.p236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Religion, aging, and health: Current status and future prospects. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1997;52B:S291–S293. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.6.s291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. A comprehensive strategy for developing closed-ended survey items for use in studies of older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2002a;57B:S263–S274. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.5.s263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-based social support and health in old age: Exploring variations by race. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2002b;57B:S332–S347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.s332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Religious meaning and subjective well-being in late life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2003;58B:S160–S170. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.3.s160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. An introduction to research on religion, aging, and health: Exploring new prospects and key challenges. In: Schaie KW, Krause N, Booth A, editors. Religious influences on health and well-being in the elderly. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2004a. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Common facets of religion, unique facets of religion, and life satisfaction among older African Americans. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004b;59B:S109–S117. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-based social support and mortality. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2006a;61B:S140–S146. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.3.s140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Exploring the stress-buffering effects of church-based and secular support on self-rated health in late life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2006b;61B:S35–S43. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Religion and health in late life. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. 6. San Diego: Academic Press; 2006c. pp. 499–518. [Google Scholar]

- Krause NM. Aging in the church: How social relationships affect health. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Tran TV. Stress and religious involvement among older Blacks. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1989;44:S4–S13. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.1.s4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Last JM. A dictionary of epidemiology. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS. Religious factors in aging, adjustment, and health: A theoretical overview. Journal of Religion and Aging. 1988;4(3/4):133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS. How religion influences morbidity and health: Reflections on natural history, salutogenesis and host resistance. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;43:849–864. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS. Religious research in gerontology, 1980–1994: A systematic review. Journal of Religious Gerontology. 1997;10(3):3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Levin J. “Bumping the top”: Is mysticism the future of religious gerontology? In: Kimble MA, McFadden SH, editors. Religion, spirituality and aging: A handbook. Vol. 2. Minneapolis: Fortress Press; 2003. pp. 402–411. [Google Scholar]

- Levin J. Religion. In: Schulz R, editor. The encyclopedia of aging. 4. II. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2006. pp. 1016–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Levin J. Integrating positive psychology into epidemiologic theory: Reflections on love, salutogenesis, and determinants of population health. In: Post SG, editor. Altruism and health: Perspectives from empirical research. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 189–218. [Google Scholar]

- Levin J. How faith heals: A theoretical model. EXPLORE: The Journal of Science and Healing. 2009;5(2):77–96. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Chatters LM. Religion, health, and psychological well-being in older adults: Findings from three national surveys. Journal of Aging and Health. 1998a;10:504–531. doi: 10.1177/089826439801000406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Chatters LM. Research on religion and mental health: An overview of empirical findings and theoretical issues. In: Koenig HG, editor. Handbook of religion and mental health. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998b. pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Levin J, Chatters LM. Religion, aging, and health: Historical perspectives, current trends, and future directions. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging. 2008;20(1–2):153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Religious effects on health status and life satisfaction among Black Americans. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1995;50B:S154–S163. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.3.s154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin J, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Religious factors in health and medical care among older adults. Southern Medical Journal. 2006;99:1168–1169. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000242810.44954.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Enders CK, Brion SL, Jain AR. The varieties of religious development in adulthood: A longitudinal investigation of religion and rational choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:78–89. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden SH. Religion and spirituality. In: Birren JE, editor. Encyclopedia of gerontology: Age, aging, and the aged. Vol. 2. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996a. pp. 387–397. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden SH. Religion, spirituality, and aging. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook on the psychology of aging. 4. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996b. pp. 162–177. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden SH. Religion, personality, and aging: A life span perspective. Journal of Personality. 1999;67:1081–1104. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden SH, Levin JS. Religion, emotions, and health. In: Magai C, McFadden SH, editors. Handbook of emotion, adult development, and aging. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 349–365. [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. On theoretical sociology: Five essays, old and new [1949] New York: The Free Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Moberg DO. Church membership and personal adjustment in old age. Journal of Gerontology. 1953;8:207–211. doi: 10.1093/geronj/8.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg DO. Religion and aging. In: Ferraro KF, editor. Gerontology: Perspectives and issues. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1990. pp. 179–205. [Google Scholar]

- Musick MA, House JS, Williams DR. Attendance at religious services and mortality in a national sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2004;45:198–213. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick MA, Koenig HG, Hays JC, Cohen HJ. Religious activity and depression among community-dwelling elderly persons with cancer: The moderating effect of race. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1998;53B:S218–S227. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.4.s218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping: Theory research, and practice. New York: The Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. Is religion nothing but… ?: Explaining religion versus explaining religion away. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Tarakeshwar N, Hahn J. Religious coping methods as predictors of psychological, physical and spiritual outcomes among medically ill elderly patients: A two year longitudinal study. Journal of Health Psychology. 2004;9:713–730. doi: 10.1177/1359105304045366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Tarakeshwar N, Ellison CG, Wulff KM. Religious coping among the religious: The relationships between religious coping and well-being in a national sample of Presbyterian clergy, elders, and members. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2001;40:497–513. [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW. Preface. In: Schaie KW, Krause N, Booth A, editors. Religious influences on health and well-being in the elderly. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2004. pp. ix–xi. [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:957–961. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Jackson JS. Religious and spiritual involvement among older African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2007;62B:S238–S250. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.s238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Levin J. Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace WL. Preface. In: Wallace WL, editor. Sociological theory: An introduction. New York: Aldine Publishing Company; 1969. pp. vii–xi. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B. Models of the stress-buffering functions of coping resources. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1985;26:352–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]