Abstract

Emotions are complex processes that are essential for survival and adaptation. Recent studies of children and animals are shedding light on how the developing brain learns to rapidly respond to signals in the environment, assess the emotional significance of this information, and in so doing adaptively regulate subsequent behavior. Here, I describe studies of children and nonhuman primates who are developing within emotionally aberrant environments. Examining these populations provides new insights on the ways in which social or interpersonal contexts influence development of the neural systems underlying emotional behavior.

Keywords: emotion, development, learning, brain plasticity, child abuse and neglect

Emotions are complex processes that organisms use to evaluate their environments, rapidly assess the significance of environmental changes, and adjust their behaviors. Over the course of (normative) development, these processes interact seamlessly and rapidly, affording successful adaptation to a variety of demands. Yet problems in emotional functioning can lead to pervasive problems in mental and physical health. Current research is examining the ways in which environmental experiences influence the complex sets of neural circuitry underlying emotional behaviors. One way to address these questions is to focus on the development of children, rodents, and nonhuman primates who receive poor or inadequate parental care; each species allows exploration of a different level of analysis. Maltreatment of human children is notoriously difficult to define, measure, and investigate empirically. Nevertheless, this phenomenon has provided an important forum for investigating the role of environmental stress, individual differences, and developmental factors in the ontogenesis of social behavior. This article begins by reviewing the kinds of emotion-regulatory problems experienced by maltreated children that appear to reflect alterations in underlying biological processes. The second half of this article focuses on the neurodevelopmental mechanisms that may account for how early experience influences affective processes.

NEUROBIOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES OF CHILD MALTREATMENT

Maltreated children experience high rates of physical and mental health problems including conduct disorders/aggression, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse; they also lag behind their peers in social skills (Mulvihill, 2005). Not surprisingly, child abuse co-occurs with a host of genetic and environmental risk factors that affect child, parent, and family functioning. It is thus difficult to evaluate where to place the occurrence of child maltreatment in the causal chain leading to behavioral problems. Experiments with nonhuman animals have provided the opportunity for careful modeling of the effects of inadequate nurturance, leading to studies of the neuroanatomical and neurophysiological substrates of emotion processing that are not feasible with humans.

Generalizations about the biological processes underlying emotional behaviors across species require caution for a number of reasons. Animal models do not always mimic human emotional disorders; brain development, structure, and function are not identical across species; there are chromosomal differences between species; and the actual behaviors exhibited by parents and the way these behaviors are received and experienced by offspring are not identical across species. But there are phenomena that do occur across species—such as poor or inadequate parental nurturance—that provide critical clues about the biological effects of child abuse. Indeed, the developmental outcomes of infant maltreatment among nonhuman primates are strikingly similar to those reported in maltreated children (Sanchez et al., 2007).

It is possible that heritable factors that co-occur with maltreatment, rather than maltreatment per se, are responsible for the behavioral difficulties observed in children. As in humans, physical abuse in rhesus monkeys has a high prevalence in some family lineages, suggesting intergenerational transmission. However, evidence from rhesus cross-fostering studies (in which infants are raised by unrelated surrogates) suggests that behavioral problems observed in monkeys are due to the post-natal experience of maltreatment rather than to genetic heritability (Maestripieri, 2005). Consistent with this view, behavioral and molecular genetic analyses support the view that the experience of abuse has a causal role in the emergence of behavioral problems in maltreated children. Current data are consistent with the position that genetic risk, in combination with early traumatic experiences, dramatically increases the likelihood of children developing mental health problems (Kim-Cohen et al., 2006).

The early experience of maltreatment appears to establish developmental trajectories of risk. One recent report revealed that individuals who were abused earlier in life demonstrated higher levels of anxiety and depression in adulthood, whereas individuals who were older at the time of the maltreatment were more likely to evince symptoms associated with aggression and substance abuse (Kaplow & Widom, 2007). To excavate the developmental processes associated with early life stress, it is also necessary to examine patterns of emotional behavior that may appear before the onset of psychological disorders. Thus, the phenomenon of early stress in the form of child maltreatment now figures prominently in considerations of the relative contributions of nature and nurture in development, and has focused attention on the neural mechanisms through which social experiences influence emotional functioning.

MECHANISMS UNDERLYING ALTERED EMOTION REGULATION IN MALTREATED CHILDREN

Cognitive Processing Mechanisms

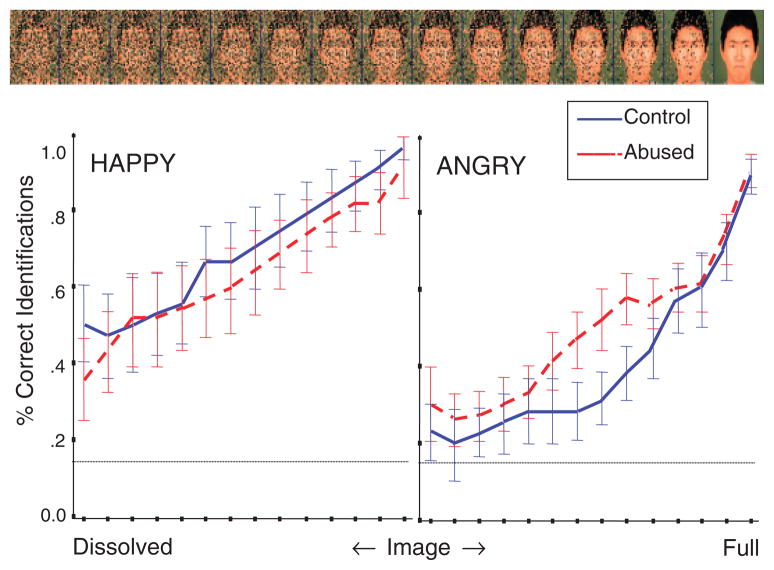

A critical question concerns how early experiences relate to the wide range of health and behavioral outcomes associated with child maltreatment. One current hypothesis is that children’s early experience alters sensory thresholds in ways that undermine effective regulation of emotion. Consistent with this view, when abused children performed a task that required them to distinguish faces that had been morphed to produce a continuum on which each face differed in signal intensity, abused children displayed enhanced perceptual sensitivity to angry facial cues. Unlike nonabused children, abused children judged ambiguous facial expressions (blends of two emotions) as “angry.” Yet abused children’s processing of other facial expressions was generally similar to that of nonmaltreated children (Pollak & Kistler, 2002). These findings are consistent with the view that infants and children adjust or tune their pre-existing perceptual mechanisms to process aspects of their environments that have become salient through learning from their social experiences (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Abused children’s accuracy at identifying happy (left graph) or angry (right graph) faces at progressive levels of image clarity, as compared to that of controls. Abused children’s accuracy is shown in red; controls are shown in blue. The figure depicts children’s accuracy as the image came into focus (the angry-face example is shown at top) with 95% confidence intervals around each group’s mean.

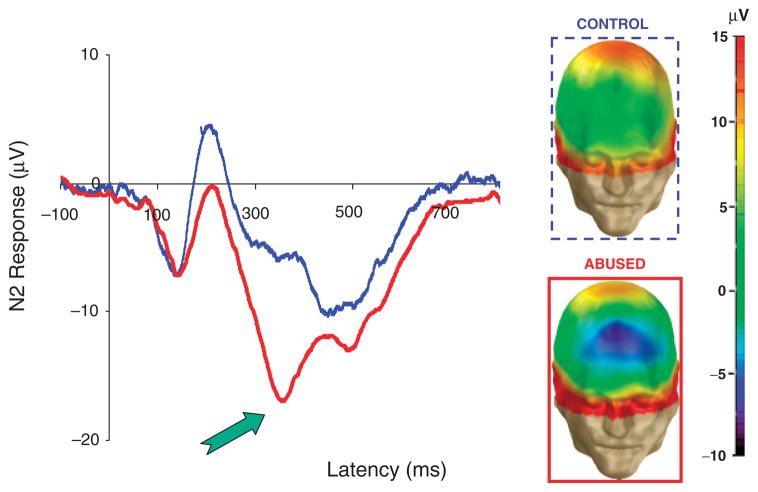

This acquired salience of certain emotional signals undermines abused children’s attentional control. Nonmaltreated children and adults attend to happy, fearful, and angry faces similarly. However, physically abused children display relative increases in brain electrical activity when actively searching for angry faces, and show rapid orienting to, as well as delayed disengagement from, anger cues. The degree of children’s attentional differences correlates with both the magnitude of abuse the child endured and the child’s degree of anxiety symptoms (Shackman, Shackman, & Pollak, 2007). This point is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows how physically abused children automatically attend to threatening cues at the expense of more contextually relevant information.

Fig. 2.

N2 response (in microvolts, μV) of the event-related potential (recorded from electrodes at the frontal region of the scalp) for children who were instructed to attend to emotional faces while ignoring angry voices. N2 is associated with inhibitory control and conflict resolution. As indicated by the arrow, abused children (red line) showed a larger N2 when trying to suppress their responses to angry voices that were irrelevant to the task than did controls (blue line). Topographic maps for control (top) and abused (bottom) children are presented alongside the waveforms and illustrate the general location of the inhibitory effect. The magnitude of this effect was related to the severity of the abuse children received.

The critical point about these studies is that while it is adaptive for salient environmental stimuli to elicit attention, successful self-regulation requires flexibility and control over these processes. We suspect that failure of regulatory capacities is a proximal link between early experience and abused children’s troubles, and makes what is adaptive within an abusive environment maladaptive in more normative social settings. Physically abused children’s processing abnormalities appear to be specific to anger, rather than being general information-processing deficits. It is thus unlikely that these effects are secondary to more global aspects of deprivation such as poverty, poor nutrition, or inadequate health care.

Neglected children also have difficulties differentiating between and responding to expressions of emotion and formulating selective attachments to caregivers (Wismer Fries, Zigler, Kurian, Jacoris, & Pollak, 2005). These social and emotional difficulties may reflect neuropsychological difficulties due to alterations in brain maturation (Prasad, Kramer, & Ewing-Cobbs, 2005). Indeed, impaired cognitive functioning in monkeys reared in isolation is associated with decreased white matter in parietal and prefrontal cortices as well as alterations in the development of hormone receptors that underlie fearful and anxious behaviors (Sanchez et al., 2007). A recent brain-imaging study revealed that the prefrontal cortex and right temporal lobe were smaller in children with maltreatment-related PTSD than in sociodemographically matched controls; these effects suggest that early stress may delay brain development (Tupler & DeBellis, 2006). Future studies using prospective high-risk designs may be able to rule out the possibility that these brain differences reflect a vulnerability to the effects of, rather than the result of, maltreatment.

One recent study (Pollak, Vardi, Bechner, & Curtin, 2005) examined attention regulation in physically abused preschoolers presented with interpersonal hostility, a situation that predicts abuse in these children’s home environments. Autonomic measures such as heart rate and skin conductance were measured in abused and nonabused children while they overheard two unfamiliar adults engage in an argument. The abused children maintained a state of anticipatory monitoring of the environment, from the time the actors began expressing anger throughout the entire experiment—even after the actors had reconciled. This response was quite distinct from that of the nonmaltreated children in the study; the nonmaltreated children showed initial arousal to the expression of anger but were better able to regulate their responses once they determined that it was not personally relevant to them. This lack of regulatory control over emotion processing is likely to guide children’s social behavior in ways that are maladaptive.

Stress Regulatory Mechanisms

Studies of nonhuman animals have long provided evidence that adverse parental care shapes the development of the neural systems believed to underlie emotional problems. Perhaps the most frequently examined system is the limbic hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis (L-HPA). The L-HPA axis is one of the threat-response systems that is particularly open to modification by experience during early life. The L-HPA system mediates neuroendocrine responses to stress, resulting in the release of steroid hormones from the adrenal gland. These hormones, glucocorticoids, affect a broad array of problems experienced by abused children, including energy mobilization, immune responses, arousal, and cognition. In a recent study, we found that a high degree or severity of neglect experienced by children was associated with long-term regulatory problems of the stress-responsive system (Wismer Fries, Shirtcliff, & Pollak, 2008). Not surprisingly, alterations in pituitary and adrenal function have been associated with illnesses common among previously abused individuals, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), fibromyalgia, hypertension, and immune system suppression.

In addition to stress hormones, other neuroactive peptides such as arginine vasopressin and oxytocin are emerging as important regulators of stress responses and critical mediators of affiliative behaviors and social recognition and memory. Oxytocin, for example, plays a critical role mediating affiliative behaviors such as maternal attachment and social bonding; oxytocin also reduces anxiety and HPA-axis responses to stress. The effects of maltreatment experiences on oxytocin neural circuits have been recently confirmed in humans as well, as demonstrated by evidence that children who experienced severe early neglect showed lower levels of salivary oxytocin reactivity as compared with controls (Wismer Fries et al., 2005). Similarly, women with histories of childhood maltreatment had lower cerebrospinal fluid levels of oxytocin than did controls (Heim et al., 2006). The study with children and the one with adults both suggested that the functioning of the oxytocin system was correlated with severity of maltreatment experienced by the individual. Reduced oxytocin activity could have a detrimental effect on affiliative behaviors and stress regulation in individuals who experienced early adversity.

Another way to evaluate brain plasticity is through the immune system, which must learn to respond to environmental pathogens encountered after an individual is born. Indeed, early life stress appears to have continued effects over development, with individuals continuing to show poor immune competence—a long-term reflection of heightened stress—years after stress has ended. For example, monkeys with high levels of maternal rejection show high inflammatory markers and low concentrations of serotonin (Sanchez et al., 2007). Similarly, adults who retrospectively recall maltreatment show sustained effects on immunity in a pattern (altered B- and cytotoxic C-cell numbers and inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein) consistent with psychological states of physiological arousal (Danese, Pariante, Caspi, Taylor, & Poulton, 2007).

Neuroanatomical Mechanisms

A related neural system of relevance to abused children’s emotion regulation is the circuitry of the amygdala, implicated in threat responses. Hariri et al. (2002) used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to directly explore the relationship between a common regulatory variant in the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) and emotional behavior in adults. Subjects performed a simple perceptual processing task involving the matching of fearful and angry human facial expressions. People carrying the less efficient 5-HTTLPR short allele exhibited increased amygdala activity in comparison to subjects homozygous for the long allele. Thus, increased anxiety and fearfulness may reflect the hyper-responsiveness of the amygdala to relevant environmental stimuli. In rhesus monkeys, high rates of maternal rejection, which co-occur with infant maltreatment, affect the development of brain serotonergic systems, resulting in increased anxiety (Maestripieri, McCormack, Lindell, Higley, & Sanchez, 2006).

Consistent findings are emerging in studies of abused children. Maltreated children with the 5-HTTLPR short allele and little social support had high levels of depression. However, maltreated children with the same genotype and similar levels of maltreatment but who had access to social support from adults showed minimal depressive symptoms (Kaufman et al., 2004). These findings are consistent with research in adults showing that 5-HTTLPR variation moderates the development of depression after stress, and suggest that negative outcomes may be modified by environmental factors that confer risk for or protection from psychological disorders.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The phenomenon of child abuse has been of interest to clinicians, educators, and public policy leaders for decades because of the clear associations between child abuse and poor mental and physical health outcomes. Contemporary research has cast important light on specific mechanisms that are responsible for the social and health risks seen in maltreated children. Drawing from neurophysiologically precise nonhuman primate studies, it appears that the modulatory role of hormonal and neurotransmitter systems may help explain risk to maltreated children. Because of their regulatory role in reactivity to threat, the prefrontal cortex and infralimbic regions appear to be central candidates for explaining the ways in which experience-dependent fine-tuning of attention, learning, emotion, and memory systems affect emotion regulation.

Important directions for future research include prospective longitudinal studies in humans that can determine whether the neurobiological correlates of early adversity are enduring long-term changes, whether short-term responses to early stress serve as risk factors for the onset of other stressors or developmental problems, and how early effects on brain and behavior may be reversed or remediated. In addition, a better understanding of how treatments work will also inform understanding of basic emotion processes in children. Developmentally informed models of the links between early experience and subsequent behavior will also require more detailed specification about how behavioral outcomes relate to variations in children’s experiences, including variations in the nature, severity, and duration of stressors, as well as more fine-grained examination of the ages at which children experienced them.

Understanding the processes through which early social experience affects child development increases the likelihood of developing effective prevention and intervention programs. But studying children who have experienced early-life stress also yields valuable knowledge about fundamental issues in psychological science. These include a focus on the neural circuitry and neurobiological regulation of emotion and their subsequent implications for behavior, as well as understanding adaptations to and consequences of chronic social-stress exposure on affective neural circuits—especially during periods of rapid neurobiological change during which the brain may be particularly sensitive to contextual or environmental influences. Ongoing research in this area is focusing on defining and specifying ways in which the environment creates long-term effects on brain and behavior, including potential corrective experiences that might foster recovery of competencies and promote health.

Recommended Reading

- Gunnar MR, Fisher PA The Early Experience, Stress, and Prevention Network. Bringing basic research on early experience and stress neurobiology to bear on preventive interventions for neglected and maltreated children. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:651–677. Provides a brief synopsis of animal models of early experience and stress neurobiology with particular focus on the impact of childhood neglect and abuse; these models are then applied to considerations of treatment and prevention strategies for vulnerable children. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Chang JJ, Kotch JB. Child maltreatment in the United States: Prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics. 2006;118:933–942. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2452. A study estimating the prevalence of child maltreatment in the United States and examining its relationship to sociodemographic factors and major adolescent health risks. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD. Early adversity and the mechanisms of plasticity: Integrating affective neuroscience with developmental approaches to psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:735–752. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050352. Theoretical paper addressing the ways in which neuroscience-based methods may be applied to understanding the neural circuitry of emotion systems and the development of psychopathology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez MM, Pollak SD. Socio-emotional development following early abuse and neglect: Challenges and insights from translational research. In: de Haan M, Gunnar MR, editors. Handbook of developmental social neuroscience. New York: Guilford Press; in press. Chapter synthesizing what is currently known about how complex sets of neural circuitry are shaped and refined over development by children’s social experience; addresses issues about the ways in which research with rodents and nonhuman primates that can be translated or applied to humans. [Google Scholar]

REFERENCES

- Danese A, Pariante CM, Caspi A, Taylor A, Poulton R. Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2007;104:1319–1324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610362104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, Kolachana B, Fera F, Goldman D, et al. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala. Science. 2002;297:400. doi: 10.1126/science.1071829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Mletzko T, Miller AH, Young LJ, Nemeroff CB. Decreased cerebrospinal fluid oxytocin concentrations associated with childhood maltreatment in adult women. Developmental Psychobiology Abstract. 2006;48:603–630. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow JB, Widom CS. Age of onset of child maltreatment predicts long-term mental health outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:176–187. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Yang BZ, Douglas-Palumberi H, Houshyar S, Lipschitz D, Krystal JH, Gelernter J. Social supports and serotonin transporter gene moderate depression in maltreated children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2004;101:17316–17321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404376101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Taylor A, Williams B, Newcombe R, Craig IW, Moffitt TE. MAOA, early adversity, and gene-environment interaction predicting children’s mental health: New evidence and a meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry. 2007;11:903–913. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D. Early experience affects the intergenerational transmission of infant abuse in rhesus monkeys. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2005;102:9726–9729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504122102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D, McCormack K, Lindell SG, Higley JD, Sanchez MM. Influence of parenting style on the offspring’s behavior and CSF monoamine metabolite levels in crossfostered and noncrossfostered female rhesus macaques. Behavioural Brain Research. 2006;175:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvihill D. The health impact of childhood trauma: An interdisciplinary review, 1997–2003. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2005;28:115–136. doi: 10.1080/01460860590950890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Kistler DJ. Early experience is associated with the development of categorical representations for facial expressions of emotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2002;99:9072–9076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142165999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Vardi S, Bechner AMP, Curtin JJ. Physically abused children’s regulation of attention in response to hostility. Child Development. 2005;76:968–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad MR, Kramer LA, Ewing-Cobbs L. Cognitive and neuroimaging findings in physically abused preschoolers. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2005;90:82–85. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.045583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez MM, Alagbe O, Felger JC, Zhang J, Graff AE, Grand AP, et al. Activated p38 MAPK is associated with decreased CSF 5-HIAA and increased maternal rejection during infancy in rhesus monkeys. Molecular Psychiatry. 2007;12:895–897. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackman JE, Shackman AJ, Pollak SD. Physical abuse amplifies attention to threat and increases anxiety in children. Emotion. 2007;7:838–852. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.4.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupler LA, De Bellis MD. Segmented hippocampal volume in children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wismer Fries AB, Shirtcliff EA, Pollak SD. Neuroendocrine dysregulation following early social deprivation in children. Developmental Psychobiology. 2008;50:588–599. doi: 10.1002/dev.20319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wismer Fries AB, Zigler T, Kurian J, Jacoris S, Pollak SD. Early experience in humans is associated with changes in neuro-peptides critical for regulating social behaviour. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2005;102:17237–17240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504767102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]