Abstract

Secretory phospholipase A2’s (sPLA2) hydrolyze glycerophospholipids to liberate lysophospholipids and free fatty acids. Although Group X (GX) sPLA2 is recognized as the most potent mammalian sPLA2 in vitro, its precise physiological function(s) remain unclear. We recently reported that GX sPLA2 suppresses activation of the Liver X receptor (LXR) in macrophages, resulting in reduced expression of LXR-responsive genes including ABCA1 and ABCG1, and a consequent decrease in cellular cholesterol efflux and increase in cellular cholesterol content (1). In this study, we provide evidence that GX sPLA2 modulates macrophage inflammatory responses by altering cellular cholesterol homeostasis. Transgenic expression or exogenous addition of GX sPLA2 resulted in a significantly higher induction of TNFα, IL-6 and COX-2 in J774 macrophage-like cells in response to LPS. This effect required GX sPLA2’s catalytic activity, and was abolished in macrophages lacking either TLR4 or MyD88. The hypersensitivity to LPS in cells over-expressing GX sPLA2 was reversed when cellular free cholesterol was normalized using cyclodextrin. Consistent with results from gain-of-function studies, peritoneal macrophages from GX sPLA2-deficient mice exhibited a significantly dampened response to LPS. Plasma concentrations of inflammatory cytokines were significantly lower in GX sPLA2-deficient mice compared to wild-type mice after LPS administration. Thus, GX sPLA2 amplifies signaling through TLR4 by a mechanism that is dependent on its catalytic activity. Our data indicate this effect is mediated through alterations in plasma membrane free cholesterol and lipid raft content.

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a disorder of lipid metabolism as well as a chronic inflammatory disease. Macrophages play a central role in the development of atherosclerosis through the cellular accumulation of lipid and the production of inflammatory mediators (2, 3). By multiple mechanisms, cellular cholesterol content plays an important role in modulating macrophage inflammatory responses. Free cholesterol loading leads to excess cholesterol in the normally cholesterol-poor endoplasmic reticulum membrane, which stimulates a stress pathway known as the unfolded protein response and subsequent activation of NF-κB and MAPK inflammatory signaling pathways (4). This pathway has been suggested to underlie the observed relationship between free cholesterol accumulation and inflammation in advanced atherosclerotic lesions (4). On the other hand, increases in plasma membrane free cholesterol have also been shown to enhance macrophage inflammatory responses through a MyD88-dependent signaling pathway that is independent of an ER stress response (5, 6). This pathway has been identified in macrophages that are deficient in ABCA1 and/or ABCG1 and hence have increased plasma membrane free cholesterol and lipid raft content due to defects in cellular cholesterol efflux. Such alterations in plasma membrane free cholesterol result in increased signaling through TLR and enhanced inflammatory responses to LPS (5, 6), a known ligand for TLR4.

The possibility that sPLA2 enzymes modulate macrophage inflammatory responses has also been the focus of investigation. Of the 10 sPLA2’s described in mammals, GX sPLA2 has the highest capacity to hydrolyze phosphatidylcholine and is therefore the most potent in hydrolyzing intact mammalian membranes in vitro (7). The generation of arachidonic acid by GX sPLA2 has the potential to give rise to a number of bioactive lipid mediators, including prostaglandins, leukotrienes, thromboxanes, and lipoxins, which are known to exert both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects. The ability of GX sPLA2 to modulate inflammatory responses in vitro and in vivo has been investigated in a number of studies, with disparate results. Treatment of primary human lung macrophages with GX sPLA2 produces a concentration-dependent increase in TNFα and IL-6 release. Interestingly, this activity was attributed to GX sPLA2’s ability to serve as a high affinity ligand for the M-type receptor rather than through the hydrolysis of membrane phospholipids (8). In contrast, overexpression of GX sPLA2 in murine macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells was reported to inhibit macrophage activation upon stimulation with LPS as evidenced by reduced cell adhesion, nitric oxide production and TNFα secretion (9). These effects were attributed to an increased production of prostaglandins E2 and J2, and enhanced release of IL-6. However, in the same study, the authors also reported that transgenic expression of GX sPLA2 in macrophages leads to fatal pulmonary defects, suggesting this enzyme plays a critical role in inflammatory lung disease (9). A recent report suggested a role for GX sPLA2 in human asthma, possibly through dysregulation of eicosanoid production (10). In a murine model of asthma, GX sPLA2 deficiency leads to significantly reduced ovalbumin-induced eicosanoid production, inflammatory cell infiltration, smooth muscle cell layer thickening, and subepithelial fibrosis (11). Mice lacking GX sPLA2 also exhibit reduced myocardial infarct size in response to ischemia/reperfusion injury, which has been attributed to attenuated neutrophil cyotoxic activities (12). More recently, GX sPLA2 was shown to induce the production of vascular endothelial growth factors by human lung macrophages through a mechanism that is independent of its catalytic activity, suggesting a role in inflammatory angiogenesis (13). Thus, available data concerning the impact of GX sPLA2 on macrophage inflammatory responses and the role of enzymatic activity and eicosanoid production on such effects have been contradictory.

Recent studies in our laboratory provide an alternative mechanism whereby GX sPLA2 may regulate macrophage inflammatory responses. We have shown that GX sPLA2 suppresses macrophage expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1, leading to reduced cellular cholesterol efflux and increased cellular cholesterol content (1). In this study we carried out comprehensive gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies to more clearly define the role of GX sPLA2 in macrophage inflammatory responses. As TLR4 signaling pathways have been shown to be modulated by plasma membrane free cholesterol and are implicated in atherosclerosis (14), we investigated whether GX sPLA2 modulates macrophage responses to LPS.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Experimental treatments

Targeted deletion of the GX sPLA2 gene was performed by InGenious Targeting Laboratory, Inc. (Stony Brook, NY) using embryonic stem cells derived from C57BL/6 mice (15). Heterozygous GX sPLA2 +/− mice were bred to produce GX sPLA2 +/+ (WT) and GX sPLA2 −/− mice (GX KO) mice that were used for the experiments. Mice deficient in TLR4 and MyD88 (16) were generously provided by Dr. L. Curtiss (Scripps Research Institute) and K. Moore (Harvard Medical School), respectively. Male and female mice (3-5 months old) were maintained on a 10-h light/14-h dark cycle and received standard mouse chow and water ad lib. For LPS treatments, mice were injected with 3μg/g body weight LPS (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, Cat # L2654). After 3 h, mice were euthanized and plasma was collected for analysis. All procedures were in accordance with the guidelines of the Veterans Affairs Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation of peritoneal macrophages (MPM)

Prior to collection of peritoneal macrophages, animals were injected intraperitoneally with a sterile solution (1 ml) of 1% Biogel 100 (Bio-Rad) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After 96 h, peritoneal macrophages were harvested by lavage with 5 ml ice-cold PBS. MPM were seeded in complete medium (DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine), and 25 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Calbiochem), allowed to attach overnight, and then washed with complete media before treating with LPS.

Stable overexpression of FLAG-tagged GX sPLA2 and the catalytically inactive mutant H46Q

Murine J774 macrophage-like cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained in complete medium. The construction of FLAG-tagged GX sPLA2 and the catalytically inactive mutant H46Q and the selection of stably transfected J774 cell lines were previously described (15). For experiments with LPS, J774 cells were incubated with 100 ng/ml LPS in the presence or absence of 0.1 μg/ml mGX sPLA2 in complete medium (DMEM medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin) prior to analysis. For other experiments, J774 cells were incubated with 100 ng/ml LPS in the presence or absence of 0.1 μg/ml mGX sPLA2 in lipoprotein-deficient medium (DMEM medium supplemented with 10% lipoprotein-deficient serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin) for 8 h prior to analysis. J774 cells were treated with 10 μM lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 10 μM arachidonic acid (AA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or vehicle (ethanol) in DMEM medium containing 1% fatty acid-free BSA for 16 h prior to treatment with 100 ng/ml LPS for 8 h.

Confocal microscopy and flow cytometry (FACS) to visualize lipid rafts

J774 cells were seeded on glass coverslips and grown until confluent in complete medium. All subsequent procedures were performed using pre-chilled solutions according to the manufacturer’s directions (Vybrant Lipid Raft Labeling Kit, Invitrogen). Cells were washed once with complete medium prior to the addition of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled Cholera Toxin-B (CTB) conjugate (1 μg/ml). Cells were incubated for 15 min at 4°C, washed with PBS, and then incubated for 15 min at 4°C with anti-CT-B antibody to cross-link CT-B and lipid rafts. After washing with PBS, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at 4°C. Fixed cells were mounted with a Prolong Antifade Kit (Molecular Probes). Confocal microscopy was performed at the University of Kentucky Imaging Facility using a Leica laser scanning confocal microscope with argon (488 nm) and krypton (568 nm) lasers. For FACS analysis, J774-C and J774-GX cells (50-70% confluent) were detached from plates, washed with chilled complete medium, and then incubated for 10 min at 4°C with 10 ng/ml Alexa Fluor 488-labeled cholera toxin B. After several washes in chilled PBS, cells were resuspended in chilled anti-CT-B antibody for 15 min at 4°C, washed, and then analyzed by flow cytometry to assess lipid rafts.

RNA extraction and qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from J774 cells or MPMs using RNeasy Mini kit (Promega). RNA (0.2-1 μg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a Reverse-transcription System (Promega). After 4-fold dilution, 5 μl was used as a template for real-time PCR. Amplification was done for 40 cycles using Power SYBR Green PCR master Mix Kit (Applied Biosystem) and IQ 5 real-time PCR machine (I Cycler, BioRad). Quantification was performed in duplicate using the standard curve method and normalized to 18S. Sequences of primers are as follows: 18s, 5′-CGG CTA CCA CAT CCA AGG AA-3′ (F) and 5′-GCT GGA ATT ACC GCG GCT-3′(R); TNFα, 5′-GGC AGG TCT ACT TTG GAG TCA TTG-3′(F) and 5′-GTT AGA AGG ACA CAG ACT GG-3′(R); IL-6, 5′-CAA CGA TGA TGC ACT TGC AG-3′(F) and 5′-GTA GCT ATG GTA CTC CAG AAG-3′ (R); COX-2, 5′-CCA GCA CTT CAC CCA TCA GTT -3′ and 5′-ACC CAG GTC CTC GCT TAT GA -3′ (R).

Cholesterol Depletion and Repletion

Cholesterol depletion and repletion of J774 cells was carried out as described by Zhu et al. (5). Briefly, cells were incubated with or without pre-warmed 10 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD, Sigma) at 37°C for 30 min to deplete cholesterol. Macrophages were then washed with PBS and incubated in the presence or absence of cholesterol coupled with MβCD (80 μg/ml, Sigma) at 37°C for 1 h to replete cholesterol. The cells were then incubated for 8 h with 100 ng/ml LPS prior to collection of culture media and cells.

Biochemical reagents and assays

FLAG-tagged fusion protein (GX sPLA2) was detected by Western blot analysis using anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Total JNK antibody was from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN); pErk, total Erk, and pJNK antibodies were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). TNFα and IL-6 protein concentrations in culture media were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The cholesterol content of J774 cells was quantified as described by Boyanovski et al (17).

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Results were analyzed by Student t-test or one way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-test. Values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data was tested for normalcy and equal variance before analysis.

Results

GX sPLA2 promotes macrophage inflammatory responses

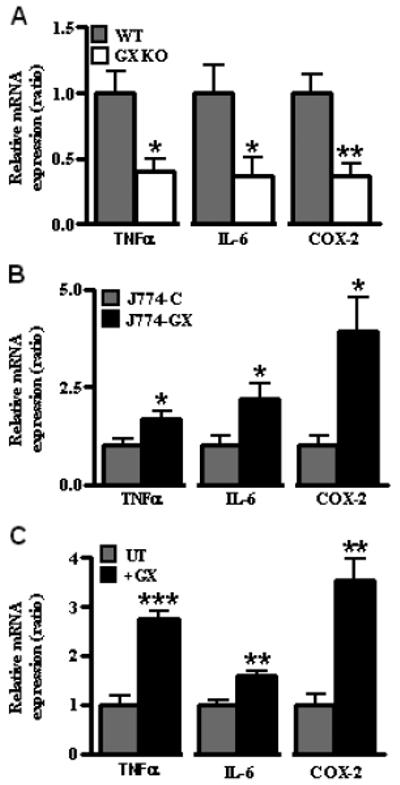

To determine whether GX sPLA2 modulates macrophage inflammatory responses, MPMs isolated from wild-type (WT) and GX sPLA2 deficient (GX KO) mice were treated with 100 ng/ml LPS for 6 h. Notably, GX KO MPMs exhibited a significantly blunted upregulation (~60% reduction) of TNF-α, IL-6, and COX-2 mRNAs in response to LPS compared to WT cells (Fig. 1A). There was no significant difference in the expression of these genes when WT and GX KO cells were incubated in the absence of LPS (not shown).

FIGURE 1. GX sPLA2 enhances macrophage inflammatory responses.

(A) Relative expression of TNFα, IL-6, and COX-2 mRNAs in peritoneal macrophages isolated from wild-type (WT) and GX sPLA2 deficient (GX KO) mice following treatment with 100 ng/ml LPS for 6 h. Values are relative to WT cells treated with LPS after normalization internally to 18S RNA. (B) Relative expression of TNFα, IL-6, and COX-2 mRNAs in cells treated with 100 ng/ml LPS for 6 h; all values are relative to J774-C cells treated with LPS after normalization internally to 18S RNA. (C) Relative expression of TNFα, IL-6, and COX-2 mRNAs in J774 cells treated for 8 h with 100 ng/ml LPS in the absence (UT) or presence (+GX) of 0.1 μg/ml recombinant GX sPLA2. Values are presented relative to control cells treated only with LPS after normalization internally to 18S RNA. (A-C) Data are means ± SEM (n = 4) and are representative of 3 independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 compared to control cells treated with LPS.

As another approach to define the role of GX sPLA2 in macrophage inflammatory responses, we performed gain-of-function studies in J774 macrophage-like cells. J774 cells were stably transfected with C-terminally FLAG-tagged GX sPLA2 (J774-GX cells). J774-GX cells secreted significantly more phospholipase activity compared to J774-C cells (4-5 fold increase; data not shown). Overexpression of GX sPLA2 did not alter the basal expression of the inflammatory mediators TNFα, IL-6 or COX-2 in J774 cells (data not shown). However, incubations with 100 ng/ml LPS resulted in a significantly increased induction of TNFα (1.7-fold), IL-6 (2.2-fold) and COX-2 (4-fold) in J774-GX cells compared to J774-C cells (Fig. 1B). Similarly, J774 cells treated with LPS in the presence of recombinant mGX sPLA2 (0.1 μg/ml; ~7 nM) exhibited a significant increase in TNFα (2.7-fold), IL-6 (1.6-fold) and COX-2 (3.6-fold) mRNA expression compared to cells treated with LPS in the absence of GX sPLA2 (Fig. 1C). Thus, our studies in MPMs and J774 cells consistently show that GX sPLA2 augments macrophage inflammatory responses.

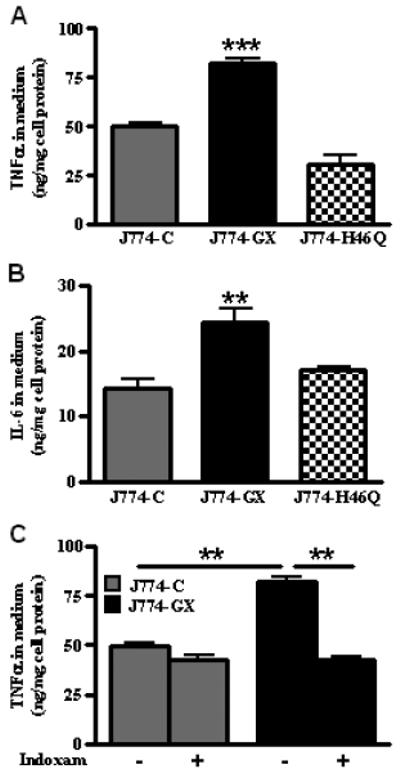

GX sPLA2 promotes macrophage inflammatory responses through a mechanism that is dependent on its catalytic activity

GX sPLA2 is known to elicit biological effects that are independent of its catalytic function (8, 13). To determine whether GX sPLA2 catalytic activity is required for its effect on macrophage responses to LPS, we developed J774 cells stably overexpressing a catalytically inactive GX sPLA2 mutant (J774-H46Q cells). As we previously reported, the amount of FLAG-tagged recombinant GX sPLA2 secreted into the media was similar for J774-H46Q and J774-GX cells, whereas the phospholipase activity in conditioned media from J774-H46Q cells was not increased compared to J774-C cells (1). Consistent with data from the analysis of mRNA (Fig. 1C), J774-GX cells treated with 100 ng/ml LPS secreted significantly more TNFα (1.7-fold) and IL-6 (1.7-fold) protein compared to J774-C cells (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, there was no significant difference in cytokine secretion between LPS-treated J774-H46Q and J774-C cells. To verify that the hyper-responsiveness of J774-GX cells was a specific effect of the transgene, cells were treated with LPS in the presence of indoxam, a specific inhibitor of sPLA2 activity (18). Indoxam significantly reduced LPS-induced TNFα secretion by J774-GX cells to a level that was similar to LPS-induced secretion by J774-C cells (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that GX sPLA2 catalytic activity is required for its ability to produce hypersensitivity to inflammatory stimuli. Although there was a trend for a blunted inflammatory response when J774-C cells were treated with indoxam, this did not reach statistical significance. Previously published studies indicate that lipoprotein particles are substrates for GX sPLA2 hydrolysis (19). Therefore, to rule out the possibility that GX sPLA2 modulates inflammation by modifying lipoproteins in the media, we carried out additional experiments with media supplemented with lipoprotein-deficient serum. Under these conditions, TNFα and IL-6 expression by J774 cells treated with LPS was blunted compared to the same cells incubated with media supplemented with FBS. Nevertheless, the addition of GX sPLA2 significantly increased the induction of cytokine expression, suggesting that lipoprotein hydrolysis was not required for this effect (Supplemental Fig. 1). Although our data is consistent with the conclusion that GX sPLA2 amplifies the effect of LPS by generating a lipid mediator, we were unable to recapitulate the enzyme’s effect by exogenous addition of 10 μM arachidonic acid or lysophosphatidylcholine, the two major products of GX sPLA2 hydrolysis (Supplemental Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. GX sPLA2 enhancement of macrophage inflammatory responses is dependent on its catalytic activity.

(A) TNFα concentrations in conditioned media from cells treated with 100 ng/ml LPS for 20 h. TNFα was not detected in media from untreated cells. (B) IL-6 concentrations in conditioned media from cells treated with 100 ng/ml LPS for 20 h. IL-6 was not detected in media from untreated cells. (C) TNFα concentrations in conditioned media from cells treated for 20 h with 100 ng/ml LPS in the presence of either vehicle or 20 μM Indoxam, a sPLA2 inhibitor. (A-C) Data are means ± SEM (n = 4) and are representative of 3 independent experiments; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

GX sPLA2 augments TLR4-dependent signaling in macrophages

TLR4/CD14/MD2 act as co-receptors that mediate LPS-induced signaling in macrophages, which is initiated by the recruitment of cytosolic adapter proteins such as MyD88 to the co-receptor complex (20, 21). Thus, it was of interest to define the role of TLR4 and MyD88 and downstream signaling pathways in GX sPLA2-mediated hyper-responsiveness. MPMs from TLR4+/+ and TLR4−/− and MyD88+/+ and MyD88−/− mice were treated with LPS in the presence or absence of 0.1 μg/ml mGX sPLA2. Consistent with the data in Fig. 1C, the addition of GX sPLA2 resulted in significantly increased cytokine expression in wild-type MPMs treated with LPS (Fig. 3A and B). As expected, the expression of the inflammatory mediators was markedly blunted in TLR4−/− and MyD88−/− MPMs treated with LPS in the absence of GX sPLA2. Notably, LPS also failed to induce inflammatory mediators in TLR4−/− and MyD88−/− MPMs in the presence of GX sPLA2, indicating that GX sPLA2 enhances inflammatory responses through a TLR4- and MyD88-dependent mechanism.

FIGURE 3. GX sPLA2 augments TLR4-dependent signaling in macrophages.

(A) Relative expression of TNFα, IL-6 and COX-2 mRNAs in MPMs isolated from TLR4+/+ and TLR4−/− mice treated for 8 h with 100 ng/ml LPS in the absence (UT) or presence (+GX) of 0.1 μg/ml GX sPLA2. Values are presented relative to TLR4+/+ cells treated with LPS alone after normalization internally to 18S RNA. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, not statistically significant compared to cells treated with LPS alone. (B) Relative expression of TNFα, IL-6 and COX-2 mRNAs in MPMs isolated from MyD88+/+ and MyD88−/− mice treated for 8 h with 100 ng/ml LPS in the absence (UT) or presence (+GX) of 0.1 μg/ml GX sPLA2. Values are presented relative to MyD88+/+ cells treated with LPS alone after normalization internally to 18S RNA. Data are means ± SEM (n=4).*p <0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, not statistically significant compared to cells treated with LPS alone. (C) Phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and JNK in WT and GX KO MPMs treated for 0 or 30 min with 100 ng/ml LPS after 18 h pretreatment with 0 or 100 ng/ml mGX sPLA2, as indicated. Cell extracts (10 μg protein) were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies.

NF-κB and MAPK signaling are major signaling pathways involved in TLR4 mediated inflammatory cytokine induction (22). Using a NF-κB promoter luciferase reporter assay, we previously reported that LPS-induced NF-κB activation is enhanced in cells overexpressing GX sPLA2 (1). Interestingly, deficiency of GX sPLA2 in MPMs was associated with a considerable reduction in LPS-induced phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and JNK that was restored by the addition of recombinant GX sPLA2 (Fig. 3C), indicating that GX sPLA2 enhances the activation of the MAPK pathway downstream of TLR4. Taken together, our data indicate that GX sPLA2 increases macrophage inflammatory responses by augmenting TLR4-dependent signaling.

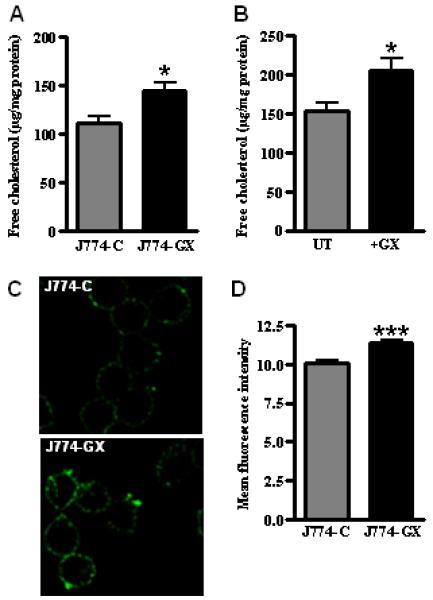

GX sPLA2 modulates cellular free cholesterol and lipid raft content

We previously demonstrated that hydrolytic products generated by GX sPLA2 negatively regulate LXR activation in macrophages and thus significantly reduce the expression of LXR target genes ABCA1 and ABCG1. As a consequence, cholesterol efflux to extracellular acceptors is blunted in macrophages by GX sPLA2 (1). Membrane free cholesterol and lipid raft content are known to modulate TLR signaling in macrophages (23-26), and the absence of ABCA1 and ABCG1 leads to the accumulation of cell membrane free cholesterol and enhanced macrophage inflammatory responses. These observations prompted us to consider whether GX sPLA2 regulates TLR4 signaling by modulating macrophage free cholesterol and lipid raft content. Overexpression of GX sPLA2 in J774 cells was associated with a significant (30%) increase in cellular free cholesterol (Fig. 4A), which compares to the 12-14% increase reported for ABCA1 deficient macrophages (5). Other published studies reported that similar changes in cellular free cholesterol content cause physiologically relevant differences in inflammatory responses (6, 24). Similarly, treatment with recombinant GX sPLA2 significantly increased the free cholesterol content of non-transfected J774 cells (Fig. 4B). Alterations in GX sPLA2 did not affect cellular cholesterol ester content in either model system (data not shown). These findings are consistent with our previous report that MPMs deficient in GX sPLA2 have significantly reduced free cholesterol compared to WT MPMs (1). Cell-surface lipid rafts were assessed by staining cells with Alexa Fluor-488 labeled cholera toxin B (CT-B), which binds to a ganglioside GM1 in lipid rafts (27). When viewed by confocal laser microscopy, J774-GX cells stained with CT-B showed increased fluorescence and more punctuate staining compared to control cells (Fig. 4C). Analysis by flow cytometry confirmed significantly increased CT-B labeling of J774-GX cells, consistent with increased lipid rafts and plasma membrane free cholesterol (Fig. 4 D) (28). Thus, our data points to a previously unrecognized role for GX sPLA2 in regulating plasma membrane lipid raft content.

FIGURE 4. GX sPLA2 enhances macrophage free cholesterol and lipid raft content.

(A) free cholesterol content of J774-C and J774-GX cells normalized to cell protein. (B) free cholesterol content of untreated J774 cells and cells treated with 0.1 μg/ml GX sPLA2 for 20 h normalized to cell protein. (C) J774-C and J774-GX cells were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488-CT-B to visualize lipid rafts. (D) J774-C and J774-GX cells were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488-CT-B and analyzed by flow cytometry to determine mean fluorescence intensity of cells. (A,B, D) Data (means ± SEM; n = 4) are representative of 3 independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001.

The hyper-responsiveness to LPS mediated by GX sPLA2 is related to altered cellular free cholesterol and lipid raft content

To determine whether increased inflammatory responses by J774-GX cells was related to increased membrane free cholesterol and lipid rafts, we manipulated plasma membrane free cholesterol content by treating cells with MβCD prior to LPS exposure. Treatment with 10 mM MβCD for 30 min reduced free cholesterol content in J774-C and J774-GX cells by 54% and 73%, respectively (Fig. 5A). Subsequent incubation of cholesterol-depleted cells for 60 min with cholesterol-loaded MβCD increased free cholesterol content in both cell types (Fig. 5A). Notably, cholesterol depletion and repletion resulted in free cholesterol levels that were no longer significantly different in the two cell types (Fig. 5A). Following each of these cholesterol manipulations, cells were treated for 8 hr with LPS and the amount of TNFα in the media was quantified. As previously shown, in the absence of cholesterol depletion/repletion LPS induced significantly more TNFα secretion in J774-GX cells compared to J774-C cells (Fig. 5B). After cholesterol depletion, the response to LPS in both cell types was significantly reduced and the hyper-responsiveness of J774-GX cells was no longer evident. In the case of cholesterol-repleted cells, the responsiveness to LPS was restored to a level that was similar for the two cell types (Fig. 5B). These data demonstrate a direct relationship between plasma membrane free cholesterol and the response to LPS, and also indicate that the hyper-responsiveness of J774-GX cells is secondary to increased plasma membrane free cholesterol content.

FIGURE 5. GX sPLA2 mediated hyperresponsiveness to LPS is reversed by plasma membrane cholesterol depletion and repletion.

(A) free cholesterol content of J774-C and J774-GX cells normalized to cell protein. Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of 10 mM MβCD at 37°C for 30 min to deplete cholesterol. Subsets of cholesterol-depleted cells were then incubated for 60 min with 1 mM MβCD -loaded cholesterol to replete cholesterol prior to LPS treatments. (B) TNFα in conditioned media from cells depicted in (A) after treatment with 100 ng/ml LPS for 8 h. (A, B) Data are means ± SEM (n > 3); **, p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. The analysis of IL-6 secretion produced similar results.

GX KO mice exhibit reduced response to LPS

To determine whether GX sPLA2 impacts inflammatory responses in vivo, WT and GX KO mice were injected with LPS (3 μg/kg body weight) or saline, and plasma cytokine levels were determined 3 h after treatment. Plasma levels of IL-6, IL-1β and TNFα were below the level of detection in both strains of mice after saline injection (data not shown). Although LPS injection evoked a marked increase in plasma cytokine levels in both WT and GX KO mice, the increase in GX KO mice was significantly blunted compared to similarly treated WT mice (25-30% decrease; Fig. 6). We interpret this data to suggest that GX sPLA2 expression augments inflammatory responses to LPS stimulation in vivo.

FIGURE 6. LPS-induced cytokine production is significantly decreased in GX KO mice compared to WT mice.

Plasma IL-6 (A), TNFα (B) and IL-1β (C) concentrations 3 h after administration of LPS (3μg/g body weight; n=6). Data are means ± SEM *, p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. Cytokines were undetectable in both genotypes after treatment with saline (not shown). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Discussion

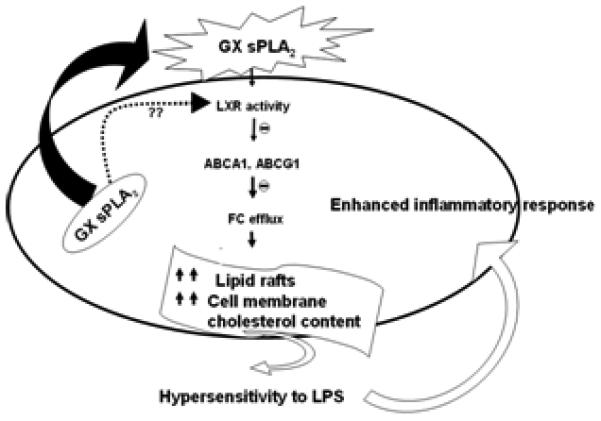

Macrophages play a key role in atherosclerosis by influencing the extent of lipid deposition and inflammation in the vessel wall (29). GX sPLA2 is expressed by macrophages and is present in atherosclerotic lesions where it has been implicated in pro-atherogenic and pro-inflammatory processes (19, 30, 31). We recently reported that GX sPLA2 negatively regulates ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression and hence reduces cellular cholesterol efflux in macrophages. These effects were dependent on GX sPLA2 hydrolytic activity and the expression of LXRα/β (1). In this study we extend these findings to show that GX sPLA2 modulation of cholesterol homeostasis in macrophages is associated with an altered response to inflammatory stimuli. Using gain-of-function and loss-of-function approaches, we demonstrate that GX sPLA2 enhances macrophage responses to LPS, a known ligand for TLR4. This hyper-responsiveness is associated with reduced ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression, reduced cellular cholesterol efflux, and increased plasma membrane free cholesterol and lipid rafts. Taken together, our results suggest that GX sPLA2 modulates inflammatory processes in macrophages by generating lipolytic products that suppress LXR target gene expression and thus promote plasma membrane cholesterol accumulation (Fig. 7). The finding that GX KO mice exhibit a blunted response to LPS provides compelling evidence that GX sPLA2 plays an important role in modulating inflammation in vivo.

FIGURE 7. Model for GX sPLA2 regulation of macrophage inflammatory responses.

GX sPLA2 enhances macrophage free cholesterol and lipid raft content, most likely by suppressing the expression of LXR targets ABCA1 and ABCG1. Increased plasma membrane free cholesterol and lipid raft content enhances TLR4 signaling. Whether GX sPLA2 hydrolyzes extracellular or intracellular phospholipid membranes, or both, is unclear.

Our conclusion that the enhancement of TLR4 signaling by GX sPLA2 is secondary to alterations in plasma membrane cholesterol and lipid raft content is consistent with previous reports that cholesterol accumulation in macrophages is associated with a pro-inflammatory phenotype (5, 6, 24, 32). Li et al. concluded that free cholesterol accumulation in macrophages leads to the induction and secretion of TNFα and IL-6 by inducing an ER stress response, which activates several inflammatory pathways including IκB kinase/NF-κB and MAPK (4). More recent studies (5, 6) suggest that changes in plasma membrane free cholesterol / lipid raft content modulate macrophage inflammatory responses through a MyD88-dependent signaling pathway that is independent of an ER stress response. Lipid rafts also play an important role in trafficking and secretion of TNFα (23). In this study we show that increased expression of GX sPLA2 leads to significantly increased cellular free cholesterol and lipid raft content, consistent with our previous finding that GX sPLA2 deficiency is associated with reduced cholesterol content in MPMs (1). We further demonstrate that the hyper-responsiveness to LPS mediated by GX sPLA2 is completely abrogated when cellular free cholesterol is normalized using cyclodextrin, a water soluble compound capable of transferring cholesterol directly to and from the plasma membrane (28, 33). Thus, our findings are analogous to previous studies in ABCG1 and/or ABCA1-deficient macrophages, where augmented TLR4 signaling was related to increases in plasma membrane lipid rafts (5, 6). Although we did not directly test whether GX sPLA2 leads to enhanced signaling through other TLRs, increased inflammatory gene responses to TLR2, TLR3, and TLR4 ligands have been demonstrated for bone marrow-derived macrophages deficient in both ABCA1 and ABCG1 (6).

According to our model (Fig. 7), GX sPLA2 modulates macrophage free cholesterol content by suppressing the activation of LXRα/β and hence the expression of LXR target genes ABCA1 and ABCG1. Interestingly, in addition to being cholesterol sensors, LXRs are known to act as negative regulators of inflammatory signaling in macrophages through a mechanism that is independent of its ability to trans-activate target genes (34). Upon activation by some ligands, LXRs are capable of blunting macrophage responses to inflammatory stimuli through trans-repression of NF-κB (35, 36). Importantly, in our previous study using a NF-κB promoter luciferase construct we ruled out the possibility that GX sPLA2 alters the trans-repressive effect of the LXR ligand T0901317 (1). Likewise, the ability of T0901317 to suppress LPS-mediated induction of IL-6 and TNFα is similar in J774-C and J774-GX cells, indicating that GX sPLA2 does not modulate the trans-repressive effect of LXR activation on inflammatory cytokine expression (data not shown).

GX sPLA2 is speculated to exhibit properties independent of its catalytic function by binding to sPLA2 receptors including the M-type receptor (13, 37) although direct evidence is lacking. Granata et al. reported that catalytically inactive GX sPLA2 was equally effective as wild-type GX sPLA2 in enhancing cytokine production in human lung macrophages (8). Our data that GX sPLA2 but not the catalytically inactive mutant H46Q enhances LPS-induced cytokine production and that indoxam blocks the effect provides strong evidence that phospholipid hydrolysis is required. However, exogenous treatment of J774 cells with hydrolytic products of GX sPLA2, arachidonic acid or lysophosphatidylcholine, did not significantly increase cytokine production in response to LPS treatment. This does not rule out the possibility that arachidonic acid or lysophosphatidylcholine mediates GX sPLA2’s effect however, since it is possible that supplementing arachidonic acid or lysophosphatidylcholine in the media complexed to BSA does not recapitulate what occurs when GX sPLA2 is continuously hydrolyzing cellular membranes. RT-PCR analysis of J774 cells and MPMs indicated absence of M-type receptor expression (data not shown), further excluding a role for this sPLA2 receptor.

Studies in gene targeted mice support the conclusion that GX sPLA2 promotes inflammatory processes in the setting of acute and chronic asthma (11) and in inflammatory lung disease (9). Most recently, Sato et al. (38) reported that pharmacological inhibition of sPLA2 significantly attenuates the acute lung inflammation and injury induced by LPS in C57BL/6J mice. The authors concluded that the protective effect was most likely due to inhibition of GV sPLA2 and GX sPLA2 activities. In a recently published study, we determined that GX sPLA2 deficiency significantly reduces abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in apoE−/− mice infused with Ang II (39). This protective effect was associated with a significantly blunted induction of inflammatory mediators in the aortas of GX sPLA2-deficient apoE−/− mice after Ang II infusion. Although GX sPLA2 is generally considered to induce proinflammatory responses in macrophages in vitro (8), one study concluded that overexpression of GX sPLA2 in RAW264.7 cells has an anti-inflammatory effect (9). Although GX sPLA2 enhanced LPS-stimulated IL-6 production in RAW264.7 cells in line with our study, TNF production was significantly suppressed (9). The basis for the discrepant effect of GX sPLA2 on TNF induction in the published study and the current study is not clear, but may be related to the different macrophage-like cell lines utilized.

Our data indicate that GX sPLA2 is not transcriptionally regulated by LPS in macrophages (data not shown). Current evidence suggests that GX sPLA2 is regulated post-translationally through proteolytic cleavage of an inactive pro-enzyme. Although the proteases(s) responsible for its proteolytic activation have yet to be identified, it is known that GX sPLA2 is expressed in an inactive form that requires removal of 11 amino acid residues at the N-terminus for catalytic activity (40). Studies utilizing transgenic mice indicate that GX sPLA2 enzymatic activity is under tight regulation, and suggest that during inflammation the inactive zymogen is proteolytically activated (41). These data and our current study provide the interesting possibility that GX sPLA2 acts in a feed-forward loop to augment macrophage responses to inflammatory stimuli.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Linda Curtiss and Dr. Kathryn Moore for providing gene-targeted mice. We also acknowledge the excellent technical assistance provided by Kathy Forrest.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the following NIH grants R01 DK082419 and P01 HL086670 (to NRW). This paper is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Lexington VAMC.

- sPLA2

- secretory phospholipase

- A2

- LXR, Liver X receptor

- COX-2

- cyclooxigenase-2

- ABCA1

- ATP-binding cassette transporter A1

- ABCG1

- ATP-binding cassette transporter G1

- MPM

- mouse peritoneal macrophage

- CTB

- cholera Toxin-B

References

- 1.Shridas P, Bailey WM, Gizard F, Oslund RC, Gelb MH, Bruemmer D, Webb NR. Group X secretory phospholipase A2 negatively regulates ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression and cholesterol efflux in macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:2014–2021. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.210237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glass CK, Witztum JL. Atherosclerosis: The road ahead. Cell. 2001;104:503–516. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis. Nature. 2000;407:233–241. doi: 10.1038/35025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Schwabe RF, DeVries-Seimon T, Yao PM, Gerbod-Giannone MC, Tall AR, Davis RJ, Flavell R, Brenner DA, Tabas I. Free cholesterol-loaded macrophages are an abundant source of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6: model of NF-kappaB- and map kinase-dependent inflammation in advanced atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21763–21772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu X, Lee JY, Timmins JM, Brown JM, Boudyguina E, Mulya A, Gebre AK, Willingham MC, Hiltbold EM, Mishra N, Maeda N, Parks JS. Increased cellular free cholesterol in macrophage-specific Abca1 knock-out mice enhances pro-inflammatory response of macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22930–22941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801408200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yvan-Charvet L, Welch C, Pagler TA, Ranalletta M, Lamkanfi M, Han S, Ishibashi M, Li R, Wang N, Tall AR. Increased inflammatory gene expression in ABC transporter-deficient macrophages: free cholesterol accumulation, increased signaling via Toll-like receptors, and neutrophil infiltration of atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation. 2008;118:1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.793869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bezzine S, Koduri RS, Valentin E, Murakami M, Kudo I, Ghomashchi F, Sadilek M, Lambeau G, Gelb MH. Exogenously added human group X secreted phospholipase A2 but not the group IB, IIA, and V enzymes efficiently release arachidonic acid from adherent mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:3179–3191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granata F, Petraroli A, Boilard E, Bezzine S, Bollinger J, Del Vecchio L, Gelb MH, Lambeau G, Marone G, Triggiani M. Activation of cytokine production by secreted phospholipase A2 in human lung macrophages expressing the M-type receptor. J Immunol. 2005;174:464–474. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curfs DM, Ghesquiere SA, Vergouwe MN, van der Made I, Gijbels MJ, Greaves DR, Verbeek JS, Hofker MH, de Winther MP. Macrophage secretory phospholipase A2 group X enhances anti-inflammatory responses, promotes lipid accumulation, and contributes to aberrant lung pathology. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21640–21648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710584200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hallstrand TS, Chi EY, Singer AG, Gelb MH, Henderson WR., Jr. Secreted phospholipase A2 group X overexpression in asthma and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007;176:1072–1078. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1088OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson WR, Jr., Chi EY, Bollinger JG, Tien Y.-t., Ye X, Castelli L, Rubtsov YP, Singer AG, Chiang GKS, Nevalainen T, Rudensky AY, Gelb MH. Importance of group X-secreted phospholipase A2 in allergen-induced airway inflammation and remodeling in a mouse asthma model. J Exp Med. 2007;204:865–877. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujioka D, Saito Y, Kobayashi T, Yano T, Tezuka H, Ishimoto Y, Suzuki N, Yokota Y, Nakamura T, Obata JE, Kanazawa M, Kawabata K, Hanasaki K, Kugiyama K. Reduction in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in group X secretory phospholipase A2-deficient mice. Circulation. 2008;117:2977–2985. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granata F, Frattini A, Loffredo S, Staiano RI, Petraroli A, Ribatti D, Oslund R, Gelb MH, Lambeau G, Marone G, Triggiani M. Production of vascular endothelial growth factors from human lung macrophages induced by group IIA and group X secreted phospholipases A2. J Immunol. 2010;184:5232–5241. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michelsen KS, Doherty TM, Shah PK, Arditi M. TLR signaling: an emerging bridge from innate immunity to atherogenesis. J Immunol. 2004;173:5901–5907. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.5901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shridas P, Bailey WM, Boyanovsky BB, Oslund RC, Gelb MH, Webb NR. Group X secretory phospholipase A2 regulates the expression of Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory Protein (StAR) in mouse adrenal glands. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20031–20039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.090423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bjorkbacka H, Kunjathoor VV, Moore KJ, Koehn S, Ordija CM, Lee MA, Means T, Halmen K, Luster AD, Golenbock DT, Freeman MW. Reduced atherosclerosis in MyD88-null mice links elevated serum cholesterol levels to activation of innate immunity signaling pathways. Nat Med. 2004;10:416–421. doi: 10.1038/nm1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyanovsky BB, Shridas P, Simons M, van der Westhuyzen DR, Webb NR. Syndecan-4 mediates macrophage uptake of group V secretory phospholipase A2-modified LDL. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:641–650. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800450-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boilard E, Rouault M, Surrel F, Le Calvez C, Bezzine S, Singer A, Gelb MH, Lambeau G. Secreted phospholipase A2 inhibitors are also potent blockers of binding to the M-type receptor. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13203–13218. doi: 10.1021/bi061376d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanasaki K, Yamada K, Yamamoto S, Ishimoto Y, Saiga A, Ono T, Ikeda M, Notoya M, Kamitani S, Arita H. Potent modification of low density lipoprotein by group X secretory phospholipase A2 is linked to macrophage foam cell formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:29116–29124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202867200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeda K, Akira S. TLR signaling pathways. Seminars in Immunology. 2004;16:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carpenter S, O’Neill LA. Recent insights into the structure of Toll-like receptors and post-translational modifications of their associated signalling proteins. Biochem J. 2009;422:1–10. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michelsen KS, Wong MH, Shah PK, Zhang W, Yano J, Doherty TM, Akira S, Rajavashisth TB, Arditi M. Lack of Toll-like receptor 4 or myeloid differentiation factor 88 reduces atherosclerosis and alters plaque phenotype in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10679–10684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403249101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kay JG, Murray RZ, Pagan JK, Stow JL. Cytokine secretion via cholesterol-rich lipid raft-associated SNAREs at the phagocytic cup. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:11949–11954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600857200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koseki M, Hirano K.-i., Masuda D, Ikegami C, Tanaka M, Ota A, Sandoval JC, Nakagawa-Toyama Y, Sato SB, Kobayashi T, Shimada Y, Ohno-Iwashita Y, Matsuura F, Shimomura I, Yamashita S. Increased lipid rafts and accelerated lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} secretion in Abca1-deficient macrophages. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48:299–306. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600428-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olsson S, Sundler R. The role of lipid rafts in LPS-induced signaling in a macrophage cell line. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Triantafilou M, Miyake K, Golenbock DT, Triantafilou K. Mediators of innate immune recognition of bacteria concentrate in lipid rafts and facilitate lipopolysaccharide-induced cell activation. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2603–2611. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.12.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guadalupe Morales-García M, Jean-Jacques Fournié M, Moreno-Altamirano MB, Rodríguez-Luna G, Ricardo-Mondragón Flores F, Sánchez-García J. A flow-cytometry method for analyzing the composition of membrane rafts. Cytometry Part A. 2008;73A:918–925. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christian AE, Haynes MP, Phillips MC, Rothblat GH. Use of cyclodextrins for manipulating cellular cholesterol content. J. Lipid Res. 1997;38:2264–2272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinberg D. Atherogenesis in perspective: hypercholesterolemia and inflammation as partners in crime. Nat Med. 2002;8:1211–1217. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishimoto Y, Yamada K, Yamamoto S, Ono T, Notoya M, Hanasaki K. Group V and X secretory phospholipase A(2)s-induced modification of high-density lipoprotein linked to the reduction of its antiatherogenic functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1642:129–138. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(03)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gora S, Lambeau G, Bollinger JG, Gelb M, Ninio E, Karabina S-A. The proinflammatory mediator Platelet Activating Factor is an effective substrate for human group X secreted phospholipase A2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:1093–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bates SR, Tao J-Q, Collins HL, Francone OL, Rothblat GH. Pulmonary abnormalities due to ABCA1 deficiency in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L980–989. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00234.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yancey PG, Rodrigueza WV, Kilsdonk EP, Stoudt GW, Johnson WJ, Phillips MC, Rothblat GH. Cellular cholesterol efflux mediated by cyclodextrins. Demonstration Of kinetic pools and mechanism of efflux. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16026–16034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zelcer N. Liver X receptors as integrators of metabolic and inflammatory signaling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:607–614. doi: 10.1172/JCI27883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castrillo A, Tontonoz P. Nuclear receptors in macrophage biology: At the Crossroads of Lipid Metabolism and Inflammation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:455–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.012103.134432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joseph SB, Castrillo A, Laffitte BA, Mangelsdorf DJ, Tontonoz P. Reciprocal regulation of inflammation and lipid metabolism by liver X receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nm820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yokota Y, Higashino K.-i., Nakano K, Arita H, Hanasaki K. Identification of group X secretory phospholipase A2 as a natural ligand for mouse phospholipase A2 receptor. FEBS Lett. 2000;478:187–191. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01848-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sato R, Yamaga S, Watanabe K, Hishiyama S, Kawabata K.-i., Kobayashi T, Fujioka D, Saito Y, Yano T, Watanabe K, Watanabe Y, Ishihara H, Kugiyama K. Inhibition of secretory phospholipase A2 activity attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in a mouse model. Exp Lung Res. 2010;36:191–200.39.. doi: 10.3109/01902140903288026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zack M, Boyanovsky BB, Shridas P, Bailey W, Forrest K, Howatt DA, Gelb MH, de Beer FC, Daugherty A, Webb NR. Group X secretory phospholipase A2 augments angiotensin II-induced inflammatory responses and abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in apoE-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 214:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morioka Y, Saiga A, Yokota Y, Suzuki N, Ikeda M, Ono T, Nakano K, Fujii N, Ishizaki J, Arita H, Hanasaki K. Mouse Group X secretory phospholipase A2 induces a potent release of arachidonic acid from spleen cells and acts as a ligand for the phospholipase A2 receptor. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;381:31–42. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohtsuki M, Taketomi Y, Arata S, Masuda S, Ishikawa Y, Ishii T, Takanezawa Y, Aoki J, Arai H, Yamamoto K, Kudo I, Murakami M. Transgenic expression of group V, but not group X, secreted phospholipase A2 in mice leads to neonatal lethality because of lung dysfunction. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36420–36433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607975200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.