Abstract

This symptom provocation study on spider phobia investigated sources of late event-related potentials (ERPs) using sLORETA (standardized low resolution brain electromagnetic tomography). Twenty-five phobic female patients and 20 non-phobic controls were confronted with phobia-relevant, generally fear-inducing, disgust-inducing and affectively neutral pictures while an electroencephalogram was recorded. Mean amplitudes of ERPs were extracted in the time windows 340–500 ms (P300) and 550–770 ms (late positive potential, LPP). Phobics showed enhanced P300 and LPP amplitudes in response to spider pictures relative to controls. Sources were mainly located in areas engaged in visuo-attentional processing (occipital and parietal regions, ventral visual pathway). Moreover, there were sources in areas which are crucial for emotional processing and the representations of aversive bodily states (cingulate cortex, insula). Further sources were located in premotor areas reflecting the priming of flight behaviour. Our findings are in good accordance with existing brain imaging studies and underline that source localization is a useful alternative for identifying phobia-relevant cortical regions.

Keywords: sLORETA, Spider phobia, Symptom provocation, Source localization, EEG, Parietal cortex, Attention, ERP, Cingulate cortex, Insula, P300, LPP

Research highlights

► Phobics showed enhanced P300 and LPP amplitudes relative to controls. Sources were mainly located in visuo-attentional processing areas. ► Our findings are in good accordance with existing brain imaging studies. ► This study partly overcomes temporal resolution problems of fMRI studies.

1. Introduction

Spider phobia is one of the most common anxiety disorders. Fredrikson et al. (1996) reported a point prevalence of 5.6% in females. According to DSM-IV-TR criteria (APA, 2000) the disorder is characterized by persistent fear during the anticipated or actual presence of spiders. Consequently, patients avoid the phobic situation or else endure it with feelings of intense distress. Moreover they realize that their fear is excessive or unreasonable.

Numerous brain imaging studies have been conducted on the neural correlates of spider phobia (e.g. Alpers et al., 2009; Dilger et al., 2003; Hermann et al., 2009; Paquette et al., 2003; Schienle et al., 2005, 2007; Straube et al., 2007). These studies found enhanced phobia-related activity in the visual association cortex, in emotion-relevant areas (e.g. anterior cingulate cortex, insula), in memory- related regions (e.g. (para) hippocampus) and in supplementary motor areas (SMA). The functional magnetic resonance imaging technique used in the aforementioned studies provides excellent spatial resolution, but suffers from relatively low temporal resolution. Consequently, EEG (electroencephalogram) with a high temporal resolution might be helpful to complement existing findings on spider-phobic response patterns. There are several event-related potential (ERP) studies which identified enlarged P300 and LPP (late positive potential) amplitudes for phobia-relevant relative to affectively neutral stimuli (Kolassa and Miltner, 2006; Leutgeb et al., 2009, 2010; Miltner et al., 2005; Schienle et al., 2008). Enhanced amplitudes of late ERPs are however not phobia-specific, but can be regarded as general indicators of emotional significance and attention allocation (for a review see Olofsson et al., 2008).

Traditional ERP analyses do not provide information about underlying sources of electrocortical activity. To solve this problem, source localization methods can be applied to EEG data. In the past, a number of studies identified temporal lobe structures as generator of the P300 component using dipole source analysis (Hegerl and Frodl-Bauch, 1997; Rogers et al., 1991; Tarkka et al., 1995). Most of these results are based on the auditory P300 using magnetoencephalography. However, other studies applying combined intracerebral and scalp recordings provided evidence that P300 activity originates from multiple cerebral sources located in the frontal lobe, the pallidum, the thalamus, temporo–parietal and medio-temporal regions (Benar et al., 2007; Johnson, 1989; Knight et al., 1989; McCarthy et al., 1989; Picton, 1992; Yingling and Hosobuchi, 1984). Lorenzo-López et al. (2008) used sLORETA to localize age-related visual search declines: sources within the P300 time frame were detected in frontal and occipito-temporal areas, which are engaged in visual search processes. In another study, McDonald and Green (2008) investigated the ERP sources of voluntary control during visuo-spatial attention. They predominantly localized P300 sources (450–500 ms) in frontal and parietal regions involved in attentional control and pre-target biasing.

Similarly, for the LPP a widespread network of generators has been identified in the occipital and parietal cortex (Keil et al., 2002; Sabatinelli et al., 2007).

To our knowledge there is no published source localization study on symptom provocation in spider phobics. Therefore, the specific aim of the present analysis was to examine sources of disorder-related enhancements of late ERP amplitudes in spider phobics relative to nonphobic controls. We expected increased localized current density in the clinical group during the viewing of pictures depicting spiders. According to previously conducted brain imaging studies (Alpers et al., 2009; Dilger et al., 2003; Hermann et al., 2009; Paquette et al., 2003; Schienle et al., 2005, 2007; Straube et al., 2007), such regions of interest were chosen that are associated with visual processing (occipito-parietal cortex), attention (parietal cortex), motor preparation (SMA) and emotional processing (insula and cingulate cortex).

2. Results

2.1. Self-report data

Questionnaire data were compared separately between the phobic and the control group. Analyses revealed a significant group effect (phobic patients (PH), non-phobic control group (CG)) for the SPQ (Spider Phobia Questionnaire, Klorman et al., 1974) (F (1, 43) = 2290.9, p < .001; see Table 1) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, Laux et al., 1981) (F (1, 43) = 6,4 p = .015). Spider-phobic participants displayed higher symptom severity (SPQ) and were more anxious (STAI mean score: PH = 37.2 ± 9.8; CG = 31.2 ± 4.9). Depression symptoms (BDI, Beck Depression Inventory , Hautzinger et al., 1993) as well as overall disgust sensitivity (QADS; Questionnaire for the Assessment of Disgust Sensitivity, Schienle, 2002) did not differ between the groups.

Table 1.

Behavioral and affective responses (means, M and standard deviations, SD) of phobic (PH) and control group (CG) participants.

| Group | Phobics M (SD) |

Controls M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| SPQ | 23.4 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.7) |

| BDI | 5.0 (4.3) | 3.0 (2.5) |

| STAI | 37.2 (9.8) | 31.2 (4.9) |

| QADS | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.2 (0.4) |

| Spider pictures | ||

| Valence | 1.4 (0.7) | 7.0 (1.6) |

| Arousal | 7.4 (2.2) | 2.2 (1.4) |

| Fear | 7.4 (2.1) | 1.4 (0.8) |

| Disgust | 6.6 (2.9) | 1.8 (1.3) |

| Disgust pictures | ||

| Valence | 3.1 (1.5) | 2.8 (1.5) |

| Arousal | 4.5 (1.8) | 5.2 (2.1) |

| Fear | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.8 (2.2) |

| Disgust | 6.9 (1.9) | 6.8 (1.7) |

| Fear pictures | ||

| Valence | 5.1 (2.1) | 4.2 (1.8) |

| Arousal | 3.8 (1.8) | 4.7 (2.0) |

| Fear | 3.2 (2.0) | 3.5 (2.0) |

| Disgust | 2.0 (1.6) | 1.7 (0.9) |

| Neutral pictures | ||

| Valence | 8.1 (0.3) | 7.7 (0.3) |

| Arousal | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.5) |

| Fear | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) |

| Disgust | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) |

Affective ratings (experienced valence, arousal, fear and disgust; see Table 1) were submitted separately to two-way ANOVAs with the factors group (PH, CG) and category (Spider, Disgust, Fear, Neutral). To clarify significant interactions, further analyses were conducted by means of between group one-way ANOVAs.

2.1.1. Valence

The ANOVA revealed significant main effects for group (F (1, 43) = 11.3, p = .002) and category (F (3, 129) = 103.6, p<.001) as well as a significant group × category interaction (F (3, 129) = 55.3, p < .001). Between-group analyses of individual categories revealed an effect for Spider pictures only (F (1, 43) = 238.1, p < .001). The patients gave lower valence ratings for Spider pictures than the controls.

2.1.2. Arousal

We observed a significant main effect for group (F (1, 43) = 8.8, p = .005) and category (F (3, 129) = 58.8, p < .001) as well as a significant group × category interaction (F (3, 129) = 40.3, p < .001). Between-group analyses of individual categories showed that the patients exclusively gave higher arousal ratings for Spider pictures (F (1, 43) = 87.8 p < .001).

2.1.3. Fear

We found a significant main effect for group (F (1, 43) = 356.7, p < .001) and for category (F (3,129) = 45.6, p < .001) as well as a significant group × category interaction (F (3,129) = 54.5, p < .001). Between-group analyses of individual categories were significant for Spider pictures only (F (1, 43) = 138.5, p < .001). The PH group gave higher fear ratings.

2.1.4. Disgust

The two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects for group (F (1, 43) = 667.5, p < .001) and for category (F (3,129) = 126.4, p < .001) as well as a significant group × category interaction (F (3,129) = 25.6, p < .001). Phobics gave higher disgust ratings for Spider pictures than controls (F (1, 43) = 48.5, p < .001).

Taken together, spider phobics showed high symptom severity (as indicated by the SPQ) and rated Spider pictures as more negative, arousing, fear- and disgust-inducing than controls. Additionally, the affective ratings for Disgust, Fear and Neutral pictures did not differ between phobic and control participants.

2.2. ERP data

The activation difference between phobics and controls in response to Spider–Neutral pictures was maximal at electrode Pz for the P300 (340–500 ms) and the LPP (550–770 ms). In order to test effects of symptom provocation, mean amplitudes of the P300 and LPP at Pz were submitted separately to two-way ANOVAs with factor group (PH, CG) and category (Spider, Disgust, Fear, Neutral). Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied if appropriate.

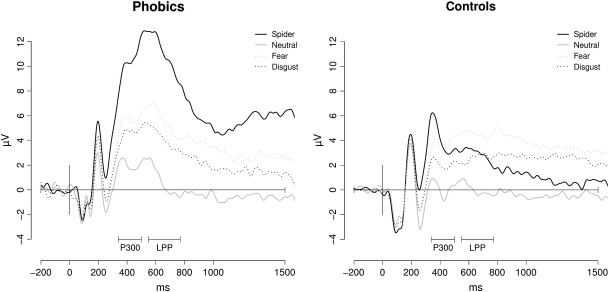

2.2.1. P300 (340–500 ms)

The two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for group (F (1, 43) = 30.1, p = .043) and for category (F (3, 129) = 53.0, p < .001) as well as a significant group × category interaction (F (3, 129) = 8.7, p < .001). Between-group analyses for separate categories showed a significant main effect for Spider pictures only (F (1, 43) = 10.9, p = .002) indicating that phobic participants showed significantly bigger amplitudes in response to Spider pictures than controls (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Grand average waveforms of phobic and control participants for Spider, Neutral, Fear and Disgust pictures at Pz.

2.2.2. LPP (550–770 ms)

The two-way ANOVA showed significant main effects for group (F (1, 43) = 54.4, p = .011) and category (F (2.2, 94.8) = 55.9, p < .001) as well as a significant group × category interaction (F (2.2, 94.8) = 21.6, p < .001). Between-group analyses for separate categories showed a significant main effect for Spider pictures only (F (1, 43) = 29.4, p < .001) with enhanced amplitudes in the patients (see Fig. 1).

Taken together, phobic patients were characterized by larger parietal P300 and LPP amplitudes in response to Spider pictures compared to controls.

2.3. sLORETA results

Significant differences in estimated current density between phobics and controls were found for the contrast Spider–Neutral only. The group effects for the contrasts Disgust–Neutral and Fear–Neutral were nonsignificant.

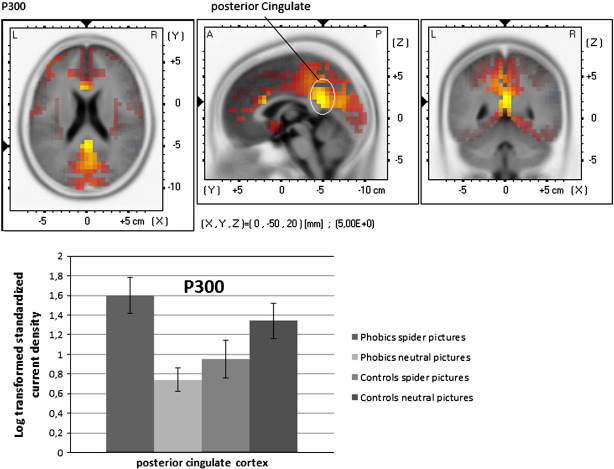

2.3.1. P300 (340–500 ms) phobics ≥ controls (contrast Spider–Neutral)

Significant higher estimated current density was observed in the phobic group compared to controls in the cingulate cortex, the cuneus, in the precuneus and in the paracentral area (Fig. 2, for a summary of the results see Table 2).

Fig. 2.

sLORETA statistical nonparametric maps comparing the current density of patients and controls for the difference Spider pictures–Neutral pictures for each ERP component (P300 and LPP). A summary of all significant regions can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Significant differences between phobic patients and healthy controls for the contrast Spider vs. Neutral pictures.

| Anatomical regions | MNI coordinates (x,y,z) | t-value |

|---|---|---|

|

(a) P300 time window Phobic's > Controls (Spider–Neutral) | ||

| Posterior cingulate | (0, −50, 20) | 5.00 |

| Cingulate gyrus | (0, −45, 25) | 4.94 |

| Precuneus | (0, −50, 30) | 4.83 |

| Anterior Cingulate | (− 5, 20, 20) | 4.76 |

| Cuneus | (0, −75, 20) | 4.38 |

| Paracentral lobule | (− 5, −45, 50) | 4.16 |

|

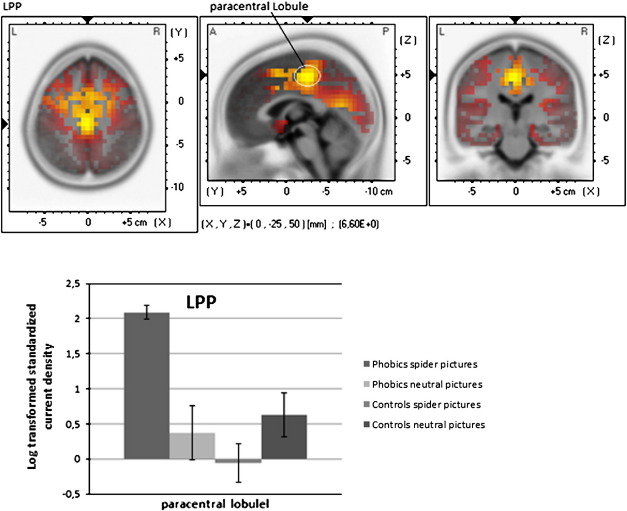

(b) LPP time window Phobic's > Controls (Spider–Neutral) | ||

| Paracentral lobule | (0, −25, 50) | 6.60 |

| Cingulate gyrus | (− 5, −20, 45) | 6.59 |

| Posterior cingulate | (− 5, −65, 10) | 6.32 |

| Medial frontal gyrus | (0, −25, 55) | 6.30 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | (5, 10, 55) | 6.22 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | (− 25, −5, 45) | 6.20 |

| Cuneus | (− 5, −65, 5) | 6.14 |

| Precuneus | (− 5, −65, 20) | 5.86 |

| Precentral gyrus | (− 35, 5, 40) | 5.78 |

| Anterior cingulate | (− 5, 10, 25) | 5.25 |

| Postcentral gyrus | (− 60, 15, 30) | 4.94 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | (− 45, 5, 35) | 4.88 |

| Insula | (35, −20, 20) | 4.87 |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | (10, −50, 0) | 4.73 |

t-values correspond to corrected p < .05 (MNI = Montreal Neurological Institute; L = left; R = right; ).

2.3.2. LPP (550–770 ms) phobics≥controls (contrast Spider–Neutral)

Estimated current density was significantly higher in phobics compared to controls in the paracentral region, in the cingulate cortex and in superior and medial frontal regions. Further significant differences were found in the cuneus and precuneus, in the pre- and postcentral gyrus as well as in the insula and in the parahippocampal gyrus (Fig. 3, for a summary of the results see Table 2).

Fig. 3.

sLORETA statistical nonparametric maps comparing the current density of patients and controls for the difference Spider pictures–Neutral pictures for each ERP component (P300 and LPP). A summary of all significant regions can be found in Table 2.

3. Discussion

This study focused on source localization of late event-related positivity during symptom provocation in spider phobia. We replicated findings by Leutgeb et al. (2009) with regard to ERPs and subjective ratings. Phobics perceived spider pictures as highly arousing, negative, fear- and disgust-inducing. This was accompanied by enhanced parietal P300 and LPP amplitudes. These findings are in line with EEG studies on spider phobia of other research groups (Kolassa et al., 2005; Miltner et al., 2005; Mühlberger et al., 2006; Schienle et al., 2008). Taken together, the results reflect enhanced allocation of attentional resources to disorder-relevant stimuli in spider phobics.

The P300/LPP generators were found in a widespread network of brain regions, which were more activated in spider phobics than in healthy controls during symptom provocation. Consistent with the findings of other research groups (e.g. Anderer et al., 2003) who located the P300 in parieto-occipital areas, we also identified P300 sources in this region (cuneus, precuneus). The cuneus is known to be a key structure for attention and for the detection of salient stimuli (Cavanna and Trimble, 2006). Obviously, the patients displayed stronger allocation of attention to phobia-relevant stimuli relative to healthy controls. This increased attention is also mirrored in an extended cingulate cortex involvement including anterior as well as posterior areas (Bush et al., 2000).

LPP sources were predominantly found in paracentral regions but also in the cingulate cortex, in frontal regions, in the insula and in the parahippocampal gyrus. This source pattern is partly in line with findings of Sabatinelli et al. (2007) who detected LPP generators in lateral occipital, inferior temporal and medial parietal regions. The superior frontal cortex plays a role in metacognitive/ executive top-down processes, which refer to the ability to monitor and control information processing necessary to produce voluntary action (Hoshi, 2006). An enhanced activation of the superior frontal cortex which also contains the supplementary motor area (SMA) has also been shown in fMRI experiments on spider phobia (e.g. Schienle et al., 2007). The SMA plays a role in preparing and organizing voluntary movement (Cunnington et al., 2005). Increased activation might reflect patients’ urge to flee during the confrontation with the feared object. This link between sensorimotor system and affective/cognitive function is in line with the theory about embodied cognition (Garbarini and Adenzato, 2004). According to the embodied cognition theory, the neural system is activated during observing an object as-if the observer were interacting with it. Gallese (2000, p.31) stated: “To observe objects is therefore equivalent to automatically evoking the most suitable motor program required to interact with them. Looking at objects means unconsciously ‘simulate’ a potential action”. Taking this theory and our findings, it seems reasonable to assume that an activation of premotor areas is linked with ‘simulated’ motor action to flee during confrontation with the feared object.

The finding of enhanced current density in the insular cortex was not surprising as this region belongs to an integrative neural system which is involved in the representation of aversive bodily states and somatic arousal (Damasio et al., 2000).

Greater activation of the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex in phobic patients within the LPP time range can be interpreted as deeper processing of arousing stimuli. The anterior cingulate cortex is part of a circuit involved in a form of attention that serves to regulate emotional processing (Bush et al., 2000). A similar function has been ascribed to the posterior cingulate cortex (Vogt et al., 2006). Although this region is not part of an emotion system per se it uses information from visual systems in order to evaluate emotional content. Our findings are also in accordance with Qin and Han (2009) who reported that the identification of risky environmental events provoked enlarged centro-parietal LPPs in the posterior cingulate cortex as estimated by the LORETA algorithm.

A further interesting observation concerned the parahippocampal source. Brain imaging studies have shown that the parahippocampal region is involved in panic attacks in individuals suffering from panic disorder (Reiman et al., 1984; Reiman et al., 1986). Behaviourally, both phobic and panic disorders are characterized by strong avoidance behaviour, which arises from intense fear. Phobic avoidance represents a type of contextual learning comparable to that seen in fear conditioning in animals (Phillips and LeDoux, 1992). In humans, the contextual fear memory involves the hippocampal formation (Bechara et al., 1995). Considering the activation of the posterior cingulate cortex which is engaged in episodic memory retrieval (Cavanna and Trimble, 2006) and the hippocampus activation, one can argue that involuntary activation of memory contents play a crucial role in the processing of phobia-relevant visual stimuli.

Leutgeb et al. (2009) discussed the enhanced phobia-related P300 and LPP components as indicators of automatic attention focusing. Consistent with this interpretation we believe that the ERP generators found in the present investigation form a network that accentuates early perceptual processing of disorder-relevant stimuli, ascribes emotional meaning to them and prepares voluntary movements to withdraw from the feared objects.

As a limitation of the present study it can be noted that the selection of time windows for the source localization was informed by previous event-related potential studies (e.g. Leutgeb et al., 2009; Olofsson et al., 2008). However, the predefinition of time windows will become unnecessary, when the temporal dynamics and interconnections between brains areas are modeled explicitly (e.g. Dynamic Causal Model, Kiebel et al., 2008). Moreover, we only included women in this study due to the higher prevalence of spider phobia in the female population. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to men.

Taken together our results give new insights into the processing of phobic stimuli with regard to the localization of involved brain regions as well as to their temporal functioning. Hence, this study partly overcomes temporal resolution problems of fMRI studies (Schienle and Schäfer, 2009).

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Participants

Twenty-five female phobic patients (PH; mean age 28.4 ± 10.7 years) and 20 non-phobic female controls (CG; mean age 24.2 ± 3.8 years) which did not differ in their mean age, participated in this study. The sample had been restricted to females since the prevalence of spider phobia is markedly higher in the female population (sex ratio: 4:1; Fredrikson et al., 1996). All subjects underwent a diagnostic session which was conducted by a board-certified clinical psychologist to diagnose spider phobia (DSM-IV-TR: 300.29) and to ensure that controls did not suffer from any mental disorder. Phobic patients who suffered from a mental disorder besides spider phobia were excluded from the sample. All participants were recruited via an article in the local newspaper and announcements at the campus. They gave written informed consent after the study had been explained to them. This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by a local ethic committee.

4.2. Stimuli and experimental paradigm

At the beginning of the study, participants underwent a diagnostic interview (Margraf, 1994). Subsequently, they filled out the SPQ, the QADS, the trait scale of the STAI, and the BDI.

In a subsequent EEG experiment participants were exposed to 160 pictures depicting four different emotional categories: ‘Spider’, ‘Fear’, ‘Disgust’ and ‘Neutral’ (40 pictures for each category). Stimuli were collected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS, Lang et al., 1999; used IAPS pictures: 1300, 1302, 1302, 1321, 1560, 1930, 1931, 2690, 3500, 3530, 5940_1, 5972, 6211, 6212, 6230, 6250_2, 6312, 6350, 6370, 6510, 6530, 6540, 6940, 9600, 9910, 9921) and a second picture set for disgust-relevant pictures (Schienle et al., 2005). The phobia-related stimuli depicted spiders in different environments. Disgust-relevant pictures represented different domains like ‘repulsive animals’ or ‘poor hygiene’. Fear-related pictures showed predators (e.g., shark, lion) or attacks by humans (e.g., with knives, pistols), whereas neutral pictures consisted of household articles, or geometric figures. The pictures were identical with those used in previous studies (Schienle et al., 2005; Schienle et al., 2008). Comparable complexity, color and brightness, between the categories, were the main criteria for the selection of the pictures. The pictures were presented in random order for 1500 ms each with an inter-stimulus interval that varied between 1500 and 5500 ms. After picture presentation, participants were asked to rate the affective quality of the picture categories by means of the Self-Assessment-Manikin (SAM; Bradley and Lang, 1994) for valence and arousal and they were asked to rate the induced disgust and fear on 9 point Likert scales (range 1–9, 9 = very positive, aroused, disgusted, anxious).

4.3. EEG recordings

EEG was recorded with a Brain Amp 32 system (Brain Vision, Gilching, Germany) using an Easy-Cap electrode system (EASYCAP GmbH, Herrsching-Breitbrunn, Germany) with 29 electrodes placed at Fp1, Fp2, F3, F4, F7, F8, Fc1, Fc2, Fc5, Fc6, C3, C4, T7, T8, Cp1, Cp2, Cp5, Cp6, P3, P4, P7, P8, O1, O2, Fz, Cz, Pz, including the mastoids Tp9 and Tp10. All electrodes were referenced to FCz. Supplementary, a horizontal electrooculogram (EOG) was recorded from the epicanthus of each eye, and a vertical EOG from the infra-orbital position of the right eye. All impedances of EEG electrodes were kept below 5kOhm. The EEG data was recorded with a sample rate of 200 Hz and filtered on-line with a band-pass of 0.016–70 Hz.

4.4. Data analysis

EEG data were analysed using Brain Vision Analyzer software (Version 2.0, Brain Vision, Gilching Germany).The EEG was digitally filtered off-line with a 20 Hz/ 24 dB/ octave low-pass filter. To correct for EOG artefacts, independent component analysis (ICA) was computed. ICs contributing to typical EOG artefacts (blinks, saccades) were identified by visual inspection of topography as well as comparison to EOG channels and afterwards deleted. Furthermore, data were re-referenced to linked mastoids (Tp9, TP10) and segmented into epochs of 1500 ms starting 200 ms before stimulus onset. Remaining artefacts (EMG, movements) were identified and removed. Baseline-correction (using the 200 ms before stimulus-onset as reference) was performed for all segments. Average ERPs time locked to Spider, Fear, Disgust and Neutral pictures were computed for each participant separately. The magnitude of the P300 component was then measured as the averaged amplitude between 340 and 500 ms post-stimulus. The same procedure was conducted for the LPP (550–770 ms). To examine the electrode side with maximal difference in amplitude for the contrast “Spider pictures – Neutral pictures”, we computed difference maps using the Brain Vision Analyzer software and MATLAB (R2010a, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, Massachusetts). Subsequently the maximal difference in the EEG map was visually verified.

4.5. Source localization analysis

On the basis of the scalp-recorded electric potential distribution, sLORETA was used to compute the cortical three-dimensional distribution of current density for the P300 and LPP time windows between affective Pictures (Spider, Disgust and Fear) and Neutral pictures as well as between both groups (phobics and controls). The sLORETA method finds a particular solution to the non-unique EEG inverse problem by assuming similar activation of neighbouring neuronal sources, followed by an appropriate standardization of the current density, producing images of electric neuronal activity (Pascual-Marqui, 2002).

Computations were made in a realistic head model (Fuchs et al., 2002), using the MNI152 template (Mazziotta et al., 2001) with the three-dimensional solution space restricted to cortical grey matter. The intracerebral volume is partitioned in 6239 voxels at 5 mm spatial resolution. Anatomical labels are reported using an appropriate correction from MNI to Talairach space (Brett et al., 2002). Hence, sLORETA images represent the electric activity at each voxel in neuroanatomic Talairach space (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988) as the squared standardized magnitude of the estimated current density.

The sLORETA software (http://www.uzh.ch/keyinst/loreta.htm) was used to perform voxel-by-voxel between-group comparison of the ERPs current density distribution. Specifically, in order to identify possible differences in the brain, the built-in voxelwise randomisation tests (5000 permutations) based on statistical non-parametric mapping (SnPM; for details see Holmes et al., 1996) corrected for multiple comparisons was performed for each picture contrast between the two groups. The results for the contrast Phobic subjects (Spider vs. Neutral pictures) vs. Control subjects (Spider vs. Neutral pictures) correspond to t-statistics maps of log-transformed data for each voxel, with corrected p < .05. Additionally, for significant peaks in each time window, we extracted the voxel intensity at the source peak as the log-transformed squared standardized magnitude of the estimated current density.

References

- Alpers G.W., Gerdes A.B.M., Lagarie B., Tabbert K., Vaitl D., Stark R. Attention and amygdala activity: an fMRI study with spider pictures in spider phobia. J. Neural Transm. 2009;116:747–757. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. DSM-IV-TR. [Google Scholar]

- Anderer P., Saletu B., Semlitsch H.V., Pascual-Marqui R.D. Non-invasive localization of P300 sources in normal aging and age-associated memory impairment. Neurobiol. Aging. 2003;3:463–479. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A., Tranel D., Damasio H., Adolphs R., Rockland C., Damasio A.R. Double dissociation of conditioning and declarative knowledge relative to the amygdala and hippocampus in humans. Science. 1995;5227:1115–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.7652558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benar C.G., Schon D., Grimault S., Nazarian B., Burle B., Roth M., Badier J.M., Marquis P., Liegeois-Chauvel C., Anton J.L. Single-trial analysis of oddball event-related potentials in simultaneous EEG-fMRI. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2007;7:602–613. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley M.M., Lang P.J. Measuring emotion: the Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 1994;1:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett M., Johnsrude I.S., Owen A.M. The problem of functional localization in the human brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:243–249. doi: 10.1038/nrn756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G., Luu P., Posner M.I. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000;4:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanna A.E., Trimble M.R. The precuneus: a review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain. 2006;3:564–583. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnington R., Windischberger C., Moser E. Premovement activity of the pre-supplementary motor area and the readiness for action: studies of time-resolved event-related functional MRI. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2005;5–6:644–656. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio A.R., Grabowski T.J., Bechara A., Damasio H., Ponto L.L., Parvizi J., Hichwa R.D. Subcortical and cortical brain activity during the feeling of self-generated emotions. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;10:1049–1056. doi: 10.1038/79871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilger S., Straube T., Mentzel H., Fitzek C., Reichenbach J.R., Hecht H., Krieschel S., Gutberlet I., Miltner W.H. Brain activation to phobia-related pictures in spider phobic humans: an event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neurosci. Lett. 2003;1:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrikson M., Annas P., Fischer H., Wik G. Gender and age differences in the prevalence of specific fears and phobias. Behav. Res. Ther. 1996;1:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs M., Kastner J., Wagner M., Hawes S., Ebersole J.S. A standardized boundary element method volume conductor model. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2002;5:702–712. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallese V. The inner sence of action: agency and motor representations. J. Consciousness Stud. 2000;7:23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarini F., Adenzato M. At the root of embodied cognition: cognitive science meets neurophysiology. Brain Cogn. 2004;56:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hautzinger M., Bailer M., Worall H., Keller F. Huber; Bern: 1993. Beck-Depressions-Inventar. [Google Scholar]

- Hegerl U., Frodl-Bauch T. Dipole source analysis of P300 component of the auditory evoked potential: a methodological advance? Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging. 1997;2:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(97)03129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann A., Schafer A., Walter B., Stark R., Vaitl D., Schienle A. Emotion regulation in spider phobia: role of the medial prefrontal cortex. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2009;3:257–267. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A.P., Blair R.C., Watson J.D.G., Ford I. Nonparametric analysis of statistic images from functional mapping experiments. In: Myers R., Cunningham V., Bailey D., Jones T., editors. Nonparametric Analysis of Statistic Images from Functional Mapping Experiments. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. pp. 334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi E. Functional specialization within the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex: a review of anatomical and physiological studies of non-human primates. Neurosci. Res. 2006;2:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J.R. Auditory and visual P300s in temporal lobectomy patients: evidence for modality-dependent generators. Psychophysiology. 1989;6:633–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1989.tb03165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil A., Bradley M.M., Hauk O., Rockstroh B., Elbert T., Lang P.J. Large-scale neural correlates of affective picture processing. Psychophysiology. 2002;5:641–649. doi: 10.1017.S0048577202394162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiebel S.J., Garrido M.I., Moran R.J., Friston K.J. Dynamic causal modelling for EEG and MEG. Cogn. Neurodyn. 2008;2:121–136. doi: 10.1007/s11571-008-9038-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klorman R., Weerts T.C., Hastings J.E., Melamed B.G., Lang P.J. Psychometric description of some specific-fear questionnaires. Behav. Ther. 1974;3:401–409. [Google Scholar]

- Knight R.T., Scabini D., Woods D.L., Clayworth C.C. Contributions of temporal-parietal junction to the human auditory P3. Brain Res. 1989;1:109–116. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90466-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolassa I., Miltner W.H.R. Psychophysiological correlates of face processing in social phobia. Brain Res. 2006;1:130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolassa I., Musial F., Mohr A., Trippe R.H., Miltner W.H.R. Electrophysiological correlates of threat processing in spider phobics. Psychophysiology. 2005;42(5):520–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang P.J., Bradely M.M., Cuthbert B.N. Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida; Gainsville, FL: 1999. International Affective Picture System. [Google Scholar]

- Laux L., Glanzmann P., Schaffner P., Spielberger L. Weinheim; Beltz Testgesellschaft: 1981. Das State-Trait-Angstinventar. [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb V., Schäfer A., Schienle A. An event-related potential study on exposure therapy for patients suffering from spider phobia. Biol. Psychol. 2009;3:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb V., Schäfer A., Köchel A., Scharmüller W., Schienle A. Psychophysiology of spider phobia in 8- to 12-year-old girls. Biol. Psychol. 2010;85(3):424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-López L., Amenedo E., Pascual-Marqui R.D., Cadaveira F. Neural correlates of age-related visual search decline: a combined ERP and sLORETA study. Neuroimage. 2008;2:511–524. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margraf J. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg: 1994. Diagnostisches Kurz-Interview bei psychischen Störungen. MINI-DIPS. [Google Scholar]

- Mazziotta J., Toga A., Evans A., Fox P., Lancaster J., Zilles K., Woods R., Paus T., Simpson G., Pike B., Holmes C., Collins L., Thompson P., MacDonald D., Iacoboni M., Schormann T., Amunts K., Palomero-Gallagher N., Geyer S., Parsons L., Narr K., Kabani N., Le Goualher G., Boomsma D., Cannon T., Kawashima R., Mazoyer B. A probabilistic atlas and reference system for the human brain: International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2001;1412:1293–1322. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy G., Wood C.C., Williamson P.D., Spencer D.D. Task-dependent field potentials in human hippocampal formation. J. Neurosci. 1989;12:4253–4268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-12-04253.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J.J., Green J.J. Isolating event-related potential components associated with voluntary control of visuo-spatial attention. Brain Res. 2008;1227:96–109. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltner W.H.R., Trippe R.H., Krieschel S., Gutberlet I., Hecht H., Weiss T. Event-related brain potentials and affective responses to threat in spider/snake-phobic and non-phobic subjects. Neurobiology of fear and disgust. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2005;1:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühlberger A., Wiedemann G., Hermann M.J., Pauli P. Phylo- and ontogenetic fears and the expectation of danger: Differences between spider- and flight-phobic subjects in cognitive and physiological response to disorder-specific stimuli. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2006;115(3):580–589. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson J.K., Nordin S., Sequeira H., Polich J. Affective picture processing: an integrative review of ERP findings. Biol. Psychol. 2008;77:247–265. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette V., Lévesque J., Mensour B., Leroux J., Beaudoin G., Bourgouin P., Beauregard M. “Change the mind and you change the brain”: effects of cognitive–behavioral therapy on the neural correlates of spider phobia. Neuroimage. 2003;2:401–409. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Marqui R.D. Standardized low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA): technical details. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002;24:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips R.G., LeDoux J.E. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav. Neurosci. 1992;2:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picton T.W. The P300 wave of the human event-related potential. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1992;4:456–479. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J., Han S. Neurocognitive mechanisms underlying identification of environmental risks. Neuropsychologia. 2009;2:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman E.M., Raichle M.E., Butler F.K., Herscovitch P., Robins E. A focal brain abnormality in panic disorder, a severe form of anxiety. Nature. 1984;5979:683–685. doi: 10.1038/310683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman E.M., Raichle M.E., Robins E., Butler F.K., Herscovitch P., Fox P., Perlmutter J. The application of positron emission tomography to the study of panic disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1986;4:469–477. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers R.L., Baumann S.B., Papanicolaou A.C., Bourbon T.W., Alagarsamy S., Eisenberg H.M. Localization of the P3 sources using magnetoencephalography and magnetic resonance imaging. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1991;4:308–321. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(91)90126-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatinelli D., Lang P.J., Keil A., Bradley M.M. Emotional perception: correlation of functional MRI and event-related potentials. Cereb. Cortex. 2007;5:1085–1091. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A. Ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung der Ekelempfindlichkeit, FEE. (A questionnaire for the assessment of disgust sensitivity, QADS) Z. Klin. Psychol. Psychother. 2002;31:110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Schäfer A. In search of specificity: functional MRI in the study of emotional experience. FMRI: advances, problems, and the future. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2009;1:22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Schäfer A., Walter B., Stark R., Vaitl D. Brain activation of spider phobics towards disorder-relevant, generally disgust- and fear-inducing pictures. Neurosci. Lett. 2005;1:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Schafer A., Hermann A., Rohrmann S., Vaitl D. Symptom provocation and reduction in patients suffering from spider phobia: an fMRI study on exposure therapy. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2007;8:486–493. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0754-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Schäfer A., Naumann E. Event-related brain potentials of spider phobics to disorder-relevant, generally disgust- and fear-inducing pictures. J. Psychophysiology. 2008;1:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Straube T., Mentzel H., Miltner W.H.R. Waiting for spiders: brain activation during anticipatory anxiety in spider phobics. Neuroimage. 2007;4:1427–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J., Tournoux P. Thieme; New York: 1988. Co-Planar Stereotaxic Atlas Of The Human Brain. [Google Scholar]

- Tarkka I.M., Stokic D.S., Basile L.F.H., Papanicolaou A.C. Electric source localization of the auditory P300 agrees with magnetic source localization. Electroencephalography Clin. Neurophys. Evoked Potentials Sect. 1995;6:538–545. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(95)00087-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt B.A., Vogt L., Laureys S. Cytology and functionally correlated circuits of human posterior cingulate areas. Neuroimage. 2006;2:452–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yingling C.D., Hosobuchi Y. A subcortical correlate of P300 in man. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1984;1:72–76. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(84)90022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]