Abstract

Study Objectives:

The homeostatic-circadian regulation of neurobehavioral functioning is not well understood in that the role of sleep dose in relation to prior wake and circadian phase remains largely unexplored. The aim of the present study was to examine the neurobehavioral impact of sleep dose at different combinations of prior wake and circadian phase.

Design:

A between-participant design involving 2 forced desynchrony protocols varying in sleep dose. Both protocols comprised 7 repetitions of a 28-h sleep/wake cycle. The sleep dose in a standard protocol was 9.33 h per 28-h day and 4.67 h in a sleep-restricted protocol.

Setting:

A time-isolation laboratory at the Centre for Sleep Research, the University of South Australia.

Participants:

A total of 27 young healthy males participated in the study with 13 in the standard protocol (age 22.5 ± 2.2 y) and 14 in the sleep-restricted protocol (age 21.8 ± 3.8 y).

Interventions:

Wake periods during both protocols were approximately 4 h delayed each 28-h day relative to the circadian system, allowing performance testing at different combinations of prior wake and circadian phase. The manipulation in sleep dose between the 2 protocols, therefore, allowed the impact of sleep dose on neurobehavioral performance to be examined at various combinations of prior wake and circadian phase.

Measurements and Results:

Neurobehavioral function was assessed using the psychomotor vigilance task (PVT). There was a sleep dose × circadian phase interaction effect on PVT performance such that sleep restriction resulted in slower and more variable response times, predominantly during the biological night. This interaction was not altered by prior wakefulness, as indicated by a nonsignificant sleep dose × circadian phase × prior wake interaction.

Conclusions:

The performance consequence of sleep restriction in our study was prominent during the biological night, even when the prior wake duration was short, and this performance consequence was in forms of waking state instability. This result is likely due to acute homeostatic sleep pressure remaining high despite the sleep episode.

Citation:

Zhou X; Ferguson SA; Matthews RW; Sargent C; Darwent D; Kennaway DJ; Roach GD. Sleep, wake and phase dependent changes in neurobehavioral function under forced desynchrony. SLEEP 2011;34(7):931-941.

Keywords: Neurobehavioral function, sleep restriction, circadian phase, prior wake, forced desynchrony, state instability

INTRODUCTION

Sound neurobehavioral functioning is essential for daily activities. The regulation of neurobehavioral function is closely related to sleep-wake regulation, which is widely believed to be underpinned by the interactions of two systems.1,2 A homeostatic system operates to balance the duration of wakefulness with the duration of sleep through an exponential saturating increase in pressure for sleep over time awake and an exponential dissipation in this pressure over time asleep. A circadian system operates to keep track of internal biological time or circadian phase such that wakefulness is promoted during the biological day and sleep is promoted during the biological night. While the influences of the two systems on neurobehavioral function have been well established, their interaction remains less clear.

Traditionally, the neurobehavioral influences of the homeostatic and circadian systems are examined through sleep, wake, and phase-dependent changes in neurobehavioral performance while the two systems are in a state of synchrony. Total sleep deprivation studies demonstrate that neurobehavioral performance declines over time awake, and that performance also fluctuates over circadian phase with a peak during the biological day and a trough during the biological night.3–5 In addition, sleep restriction studies demonstrate that an average of 7–8 h sleep per night is required for daily optimal neurobehavioral functioning.6–8 Restricting sleep dose below this optimal amount induces short-term or acute performance impairment, and persistent sleep restriction induces long-term or chronic impact such that performance impairment accumulates over days.6–8 In both types of sleep studies, however, the homeostatic and circadian systems are synchronized, such that there is a fixed phase relationship between the sleep-wake cycle and the circadian cycle. Consequently, neurobehavioral function is assessed at limited combinations of sleep dose, prior wake and circadian phase, and the homeostatic-circadian interaction is not quantified.

More recently, the interaction of the homeostatic and circadian systems in the regulation of neurobehavioral function has been examined through a forced desynchrony between the two systems. A state of desynchrony is forced through either extending or shortening the period of sleep-wake cycle (e.g., 28 h and 20 h) outside the period of entrainment for the circadian system.9 As such, sleep and wake periods coincide with different circadian phases each day, and neurobehavioral function is assessed at various combinations of circadian phase and prior wake. Forced desynchrony studies demonstrate that the homeostatic and circadian systems interact, such that neurobehavioral impairments during the biological night only become prominent when the biological night coincides with prior wakefulness > 6 h.10–13 These forced desynchrony studies, however, have kept their sleep doses constant (e.g., 9.33 h in bed/28-h day). Consequently, the role of sleep dose in the homeostatic-circadian interaction remains largely unexplored: what is the contribution of sleep dose to neurobehavioral functioning at different combinations of prior wake and circadian phase? This is a question of great theoretical and practical importance. Answers to this question would not only improve our understanding of the homeostatic-circadian regulation of neurobehavioral function, but also facilitate better predictions of neurobehavioral impairments experienced by shiftworkers who often work at various combinations of prior wake and circadian phase14 and who often do not obtain sufficient sleep.15–17

To date, only one published forced desynchrony study has examined the neurobehavioral impact of sleep dose in relation to prior wake and circadian phase.18 In that study, the sleep to wake ratio was reduced to an equivalent of 5.6 h per 24 h (i.e., 10 h per 42.85-h day) over a 3-week period. This induced a chronic impact of sleep restriction on performance. However, the finite length of sleep dose (i.e., 10 h) was longer than the habitual level, which is considered sufficient to dissipate acute sleep pressure. Consequently, the chronic impact of sleep restriction was present in the absence of an acute impact. We designed a novel protocol, in which the acute impact of sleep dose was induced by restricting the finite length of sleep dose below the habitual level (4.7 h), yet the level of chronic sleep pressure was constrained by limiting the period of sleep restriction to only one week. We compared neurobehavioral performance from this protocol to that from a standard forced desynchrony protocol in which sleep dose was not intentionally restricted. This comparison allowed us to investigate the impact of sleep restriction—to a larger extent, the acute impact of sleep restriction—at different combinations of prior wake and circadian phase. We further elaborate on the nature of neurobehavioral consequence induced by sleep restriction. We argue, based on previous observations, that sleep restriction brings about “waking state instability” or waxing and waning of attention.3,19 This waking state instability would be characterized by increased within-task response variability—at times when attention is waning responses are delayed, whereas at times when attention is waxing responses remain timely.3,19

METHODS

Participants

A total of 27 males aged between 18 to 33 years (M = 22.1 ± 3.1 y) participated in the current study. Individuals were recruited through flyers around the university community in Adelaide, Australia. The participants had a body mass index between 19 and 26 kg/m2, with an average of 22.31 (± 2.22) kg/m2. Participants' health status was assessed using a general health questionnaire. Based on the responses to the questionnaire, the participants did not have any medical conditions, psychiatric disorders, or sleep disorders; none of the participants were taking any prescribed medication or had a high consumption of alcohol or caffeine at the time of the study. The participants were not shift workers and had not undertaken transmeridian travel in the last 3 months. The participants had similar self-report habitual sleep-wake patterns, with a mean bedtime at 23.2h (± 0.8 h), a mean get-up time at 8.3 h (± 0.9 h), and a mean sleep duration of 8.1 h (± 0.9 h). This was verified through activity data collected during a week period using activity monitors and sleep diaries.

One week prior to the experiment, the participants were instructed to maintain their habitual sleep-wake pattern with a sleep opportunity of 8 h each night. Compliance was verified using activity monitors for all participants involved in the sleep-restricted protocol (see Protocols for detail) and, due to various reasons, not for all participants involved in the standard protocol. However, compared to neurobehavioral performance data from other forced desynchrony studies where participants' sleep-wake patterns prior to the experiment were strictly verified,12,13 performance of our participants in the standard protocol was better. This suggests that it is unlikely that our participants in the standard protocol have been chronically sleep restricted prior to the experiment.

Ethics

The current study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of South Australia using guidelines established by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Prior to taking part, participants were informed about the general nature of the study and gave written consent. Upon completion, each participant received financial compensation.

Apparatus

Neurobehavioral function was measured using the psychomotor vigilance task (PVT).20 Specifically, PVT is a simple reaction time task measuring sustained attention. The task requires participants to respond to a visual LED-digital counter on a portable device at its onset as quickly as possible, by pressing the response button with the thumb of the dominant hand. Interstimulus intervals varies randomly from 2,000 to 10,000 milliseconds (msec) during 10-min task duration. The dependent measures derived from PVT were mean reciprocal response time (RRT in msec−1 × 10−3), standard deviation of RRT, slowest 10% RRT, fastest 10% RRT, the number of lapses (RT > 500 msec), and the number of false starts (RT < 100 msec).

Core body temperature was sampled using rectal thermistors (Cincinnati Sub-Zero Products, Cincinnati, OH) at 1-min intervals throughout the study. Thermistors were inserted by participants 10 cm beyond the anal sphincter, and were re-adjusted when necessary. Activity level was recorded with wrist worn Acti-watches (Actiwatch-64, Philips) throughout the study. During each scheduled sleep period, sleep was recorded with standard polysomnograph (PSG) (Compumedics E-Series EEG/PSG system, Melbourne, Australia), including C3/A2 and C4/A1 electroencephalogram (EEG), right and left electrooculogram (EOG), and electromyogram (EMG). PSG recordings were then manually scored in 30-sec epochs using established criteria.21 The sleep variable estimated from the PSG recordings was total sleep time (i.e., sum of minutes spent in all sleep stages).

Protocols

The present study employed a between-participant design in which participants were assigned to one of two 28-h forced desynchrony (FD) protocols varying in sleep dose. A standard FD protocol (n = 13; age 22.5 ± 2.2 y) comprised 7 × 28-h sleep/wake cycle with a sleep dose of 9.33 h/cycle (equivalent to 8 h in bed/24-h day). A sleep-restricted FD protocol (n = 14; age 21.8 ± 3.8 y) comprised 7 × 28-h sleep/wake cycle with a sleep dose of 4.67 h/cycle (equivalent to 4 h in bed/24-h day). The imposed sleep/wake schedules during the 2 protocols are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Double raster plots of the standard (A) and sleep-restricted (B) 28-h day forced desynchrony protocols. White blocks represent scheduled wake periods, black blocks represent scheduled bed periods, and black dots represent scheduled PVT testing sessions. In both protocols, after 2 training days (TR) and a baseline day (BL), participants were scheduled to 7 repetitions of 28-h day (FD). The bed period of each 28-h day was 9.3 h in the standard protocol and 4.7 h in the sleep-restricted protocol. There was an additional recovery day (REC) in the sleep-restricted protocol.

Both protocols began with 2 training days and a baseline day, separated by two 8-h sleep periods from 00:00 to 08:00. During the training periods, 3 PVT “training” sessions were completed as research indicates that PVT has a 1-3 trial learning curve.22 During the baseline period, 5 PVT testing sessions were scheduled at 2-h intervals to establish each individual's baseline performance level.

During the FD phase of the protocols, a 1-h test battery including a PVT was completed every 2.5 h during wakefulness, with the first test battery being scheduled at 2 h after waking in order to minimize the adverse impacts of sleep inertia.23 Results on tasks other than PVT are reported elsewhere.24–26 Due to the wake extension in the sleep-restricted protocol (23.33 h scheduled wakefulness), there were 2 extra testing sessions in this protocol compared to the standard protocol (18.67 h scheduled wakefulness). All testing sessions were conducted individually in each participant's lounge room with participants seated in front of a blank wall in order to avoid distractions. Between testing sessions, only nonstrenuous activities such as watching pre-recorded TV programs and reading books were permitted. Participants spent most of their “free” time in their own lounge rooms and had minimal interaction with each other. No naps were allowed during wake periods. To ensure compliance, participants were closely monitored by researchers either in person or via a closed circuit television system. Prior to each sleep period, PSG montage was applied to the participants.

Laboratory Conditions

The study was conducted in a sound attenuated sleep laboratory at the Centre for Sleep Research, the University of South Australia, Adelaide. The laboratory was configured in such a way that (i) 3 participants were studied at a time; (ii) each participant had his own bedroom, lounge room and bathroom facilities. During the course of the study, the laboratory was maintained as a temporally isolated environment where natural lights and other time cues were not accessible. Ambient light intensity was 10–15 lux 182 cm above the floor at angle of gaze during wake periods and less than 0.03 lux during sleep periods. Throughout the study, the target ambient temperature was 22 (± 1)°C.

Circadian Estimates

Core body temperature (CBT) data from six 28-h days (i.e., FD day 2–7) were used to generate circadian phase estimates for each participant. The generation of phase estimates from CBT data was a 5-step process, which has been described in detail elsewhere.26 In brief, the steps were (i) cleaning of the raw CBT data to account for erroneous or missing values due to downloading of the data, slippage of the thermistor, or malfunction of the equipment, (ii) de-masking for physical activity using a purification by intercepts approach,27 (iii) de-masking for sleep/wake differences using a sleep-state correction factor, (iv) fitting of a cosine equation with a fundamental period and a single harmonic to the de-masked CBT data using the method of least squares, and (v) assigning a circadian phase estimate (i.e., 0°–360°, with 0° representing the minimum of the fitted core body temperature curve) to each 1 min of the FD portion of the protocol using the resultant cosine equation. The tau value of each participant was estimated based on the composite (i.e., a fundamental plus one harmonic) fitted core body temperature curve. The estimated tau values of the 27 participants ranged between 23.81 h and 24.56 h, with an average of 24.17 h (± 0.21). This average is consistent with previous reports.28

Data Analyses

Circadian phases were divided into 6 × 60° bins (i.e., equivalent to ∼ 4 h) with midpoints at 0°, 60°, 120°, 180°, 240°, and 300°. The 2 additional PVT testing sessions in the sleep-restricted protocol were excluded from data analyses. For each performance metric, each individual's performance scores during the FD phase were expressed relative to his own average performance calculated from the 5 baseline sessions, with a higher score indicating better performance. This standardization procedure served to eliminate the possibility that the performance impact of sleep dose, if any, is due to baseline performance differences between the two sleep dose groups. The standardized scores were then assigned 1 of 2 sleep dose conditions (i.e., 9.33 h and 4.76 h), 1 of 7 levels of prior wake (i.e., 2 h, 4.5 h, 7 h, 9.5 h, 12 h, 14.5 h, and 17 h), 1 of 6 circadian phase bins (i.e., 0°–300°), and 1 of 7 FD days (i.e., FD day 1–7).

For each performance metric, data were analysed using a mixed-effects regression model, with sleep dose (2 levels), prior wake (7 levels), circadian phase (6 levels), and FD day (as a continuous variable) as fixed terms and “participant” (N = 27) as a random term. We tested (i) all main effects; (ii) 4 × 2-way interactions including prior wake × circadian phase, sleep dose × FD day, sleep dose × prior wake and sleep dose × circadian phase; (iii) 1 × 3-way interaction, sleep dose × prior wake × circadian phase. The “FD day” term served to account for performance impairment due to chronic circadian misalignment during the FD phase.12,13 The “sleep dose × FD day” interaction served to account for the cumulative effects of sleep restriction on performance and/or the differential effect of circadian misalignment on performance between the 2 sleep dose conditions.7,8

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 17.0. The statistical significance of all fixed effects was determined using F tests. The denominator degree freedoms for F statistics were computed using the Satterthwaite approximation method.

RESULTS

On average, participants in the standard protocol obtained a total sleep time of 7.71 (± 0.65) hours per 28-h day, whereas participants in the sleep-restricted protocol obtained 4.49 (± 0.09) hours per 28-h day. The total sleep time during the forced desynchrony phase of both sleep dose conditions are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mean (± SEM) of total sleep time over forced desynchrony days for both sleep dose conditions. Note the error bars of the 4.7 h in bed/28-h day condition were obscured by the data points.

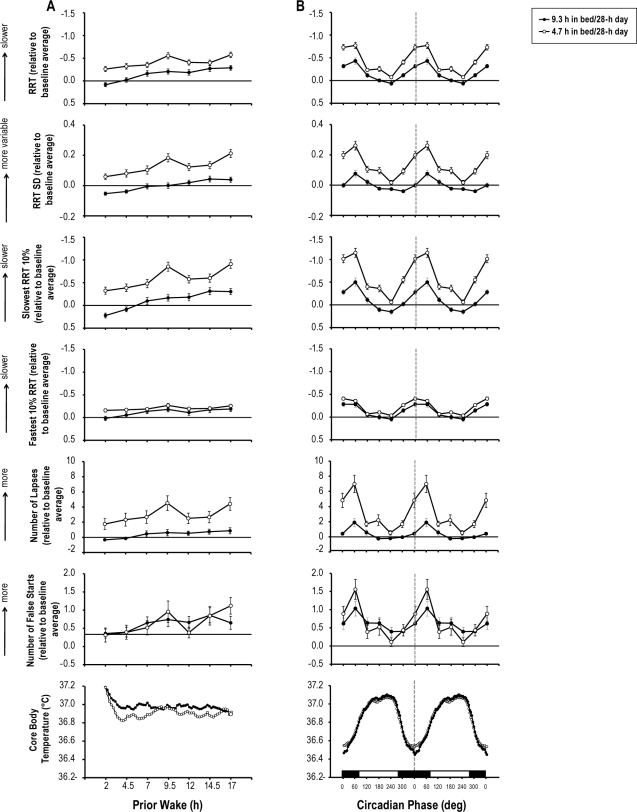

There was a main effect of prior wake on all PVT metrics (Table 1), i.e., reciprocal response time (RRT), standard deviation of RRT (RRT SD), slowest and fastest 10% RRT, the number of lapses and the number of false starts. Figure 3A presents performance on these metrics as a function of prior wake when sleep dose was low (i.e., 4.7 h in bed/28 h) and when sleep dose was high (i.e., 9.3 h in bed/28 h). It is clear that performance on these metrics worsened over time awake. Specifically, as prior wakefulness increased, participants responded more slowly and more variably, experienced more lapses, and made more errors.

Table 1.

Results of mixed-effects regression analyses (F-values) on different performance metrics of the psychomotor vigilance task

| RRT | RRT SD | slowest 10% RRT | fastest 10% RRT | no. of lapses | no. of false starts | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect | ||||||

| wake† | 17.1*** | 16.38*** | 22.13*** | 6.65*** | 4.91*** | 4.38*** |

| phase† | 63.86*** | 32.41*** | 58.87*** | 46.94*** | 22.81*** | 8.73*** |

| day† | 61.21*** | 25.09*** | 38.72*** | 28.45*** | 16.46*** | 41.69*** |

| sleep† | 0.9 | 0.01 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.2 | 0.08 |

| Two-way | ||||||

| wake · phase | 1.51* | 1.12 | 1.47* | 1.23 | 0.8 | 0.85 |

| sleep · day | 6.91** | 40.62*** | 21.49*** | 0.07 | 10.92*** | 0.21 |

| sleep · wake | 1.98 | 2.59* | 2.87** | 1.12 | 1.54 | 1.11 |

| sleep · phase | 4.49*** | 7.64*** | 6.06*** | 1.08 | 7.69*** | 3.21** |

| Three-way | ||||||

| sleep · wake · phase | 1.22 | 1.01 | 1.2 | 1.19 | 0.72 | 1.23 |

wake, prior wake; phase, circadian phase; day, forced desynchrony day; sleep, sleep dose.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Means (± SEM) of reciprocal response time (RRT), standard deviation of RRT (RRT SD), slowest 10% RRT, fastest 10% RRT, the number of lapses and the number of false starts on the psychomotor vigilance task (PVT) and mean core body temperature as a function of scheduled prior wakefulness (A) and circadian phase of core body temperature (double plotted; (B)) and when the sleep dose is 9.3 h per 28-h day and when sleep dose is 4.7 h per 28-h day. Dotted lines indicate the core body temperature minimum. The black block represents circadian phases that correspond to the biological night, and the white block represents circadian phases that correspond to the biological day. Performance scores on each metric are expressed relative to the baseline average such that after this transformation ‘0’ on each y-axis corresponds to the baseline average (i.e., horizontal lines). The y-axes for RRT, slowest and fastest 10% RRT are reversed such that a higher point indicates worse performance.

There was a main effect of circadian phase on all PVT metrics (Table 1). Figure 3B presents performance on these metrics as a function of circadian phase for the 2 sleep dose conditions. Clearly, performance on these metrics exhibited a rhythm with the worst performance occurring at the circadian phase bin 60°, i.e., shortly after the core body temperature minimum. Specifically, near the circadian nadir, participants responded more slowly and more variably, experienced more lapses, and made more errors.

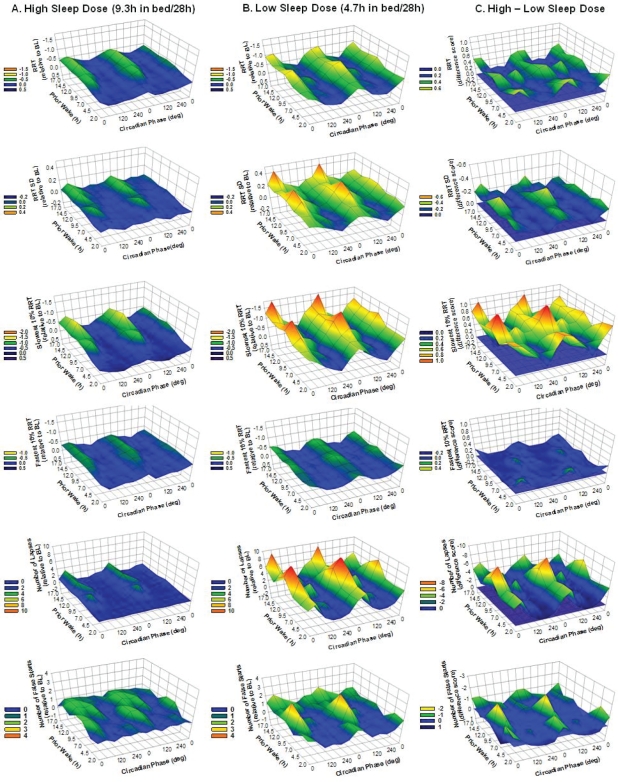

There was a significant prior wake × circadian phase interaction effect on RRT and slowest 10% RRT (Table 1). Figures 4A and 4B present performance on these metrics at different combinations of prior wake and circadian phase for both sleep dose conditions. Color changes in these contour plots reflect performance changes—the warmer the color, the worse the performance. For both sleep dose conditions, the circadian rhythm of performance on the two metrics became more pronounced over time awake, which is primarily associated with worsening of the performance nadir.

Figure 4.

Mean performance (z-axis) on selected metrics of the psychomotor vigilance task (PVT) at different combinations of scheduled prior wakefulness (y-axis) and circadian phase of core body temperature (x-axis, double plotted with 0 degree representing the core body temperature minimum). Each row shows data from the same metric, from top to bottom, reciprocal response time (RRT), standard deviation of RRT (RRT SD), slowest 10% RRT, fastest 10% RRT, the number of lapses and the number of false starts. Columns from left to right indicate the 9.3 h in bed per 28-h day condition (A), the 4.7 h in bed per 28-h day condition (B) and the difference between the 2 sleep dose conditions (C). Performance scores on each metric are expressed relative to the baseline average such that after this transformation ‘0’ on each z-axis corresponds to the baseline average. For column A and B, a higher value on the z-axis indicates worse performance relative to the baseline average (BL). For column C, a higher value on the z-axis indicates greater performance impairment such that the warmer the colour is the stronger the negative impact of sleep restriction is. To further facilitate data interpretation, each panel of column C includes a zero plain (in color blue) indicates no difference in performance between the 2 sleep dose conditions, i.e., no impact of sleep restriction.

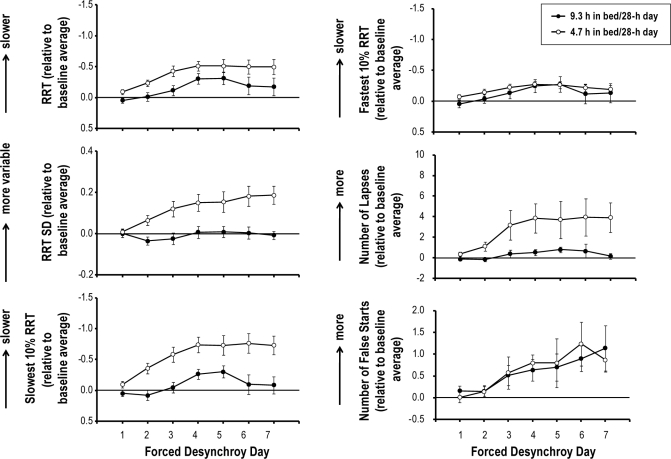

There was a main effect of FD day on all PVT metrics (Table 1). Figure 5 presents performance on these metrics over FD days when sleep dose was high and when sleep dose was low. Performance worsened over FD days for both sleep dose conditions. Specifically, as FD proceeded, participants responded more slowly and more variably, experienced more lapses, and made more errors.

Figure 5.

Means (± SEM) of reciprocal response time (RRT), standard deviation of RRT (RRT SD), slowest 10% RRT, fastest 10% RRT, the number of lapses, the number of false starts on the psychomotor vigilance task (PVT) as a function of forced desynchrony day when the sleep dose is 9.3 h per 28-h day and when sleep dose is 4.7 h per 28-h day. Performance scores on each metric are expressed relative to the baseline average such that after this transformation ‘0’ on each y-axis corresponds to the baseline average (i.e., horizontal lines). The y-axes for RRT, slowest and fastest 10% RRT are reversed such that a higher point indicates worse performance.

Sleep dose affected PVT performance through its interaction with other factors (Table 1). There was a significant sleep dose × FD day interaction effect on PVT metrics other than fastest 10% RRT and the number of false starts. Performance on these metrics declined more quickly over FD days when sleep was restricted than when sleep was not restricted, such that as FD proceeded, the impact of sleep restriction became greater. There was a significant sleep dose × prior wake interaction effect on RRT SD and slowest 10% RRT. The impact of sleep restriction on these 2 PVT metrics was more pronounced at 9.5 h and 17 h awake (Figure 3A). There was a sleep dose × circadian phase interaction for all PVT metrics other than fastest 10% RRT. The adverse impact of sleep restriction on these PVT metrics was prominent at circadian phases that correspond to the biological night, compared to circadian phases that correspond to the biological day (Figure 3B).

There was no significant sleep dose × prior wake × circadian phase interaction on any PVT metrics (Table 1). The sleep dose × circadian phase interaction was not altered by prior wake, such that the impact of sleep restriction was prominent near the circadian nadir even when the circadian nadir coincided with short wakefulness. To facilitate interpretation, the magnitudes of the impact of sleep restriction, as visualized by the differences in the mean performance scores between the 2 sleep dose conditions, are plotted at different combinations of prior wake and circadian phase (Figure 4C). Color changes in these contour plots reflect changes in the extent of the impact of sleep dose—the warmer the color, the greater the adverse impact of sleep restriction. The adverse impact of sleep restriction was prominent at circadian phases corresponding to the biological night, and over time awake the magnitude of the impact of sleep restriction did not change significantly.

DISCUSSION

By altering the sleep dose between two forced desynchrony protocols, the current study systematically assessed the neurobehavioral impact of sleep restriction at various combinations of prior wake and circadian phase. To date, this is the first forced desynchrony study to reduce both the sleep-to-wake ratio and the finite duration of sleep episodes below the habitual amount. Our results not only reinforce but also add to our knowledge of the homeostatic and circadian regulation of neurobehavioral function.

In agreement with previous forced desynchrony (FD) studies,10–12,29,30 we found independent influences of the homeostatic and circadian systems on neurobehavioral function, as indicated by the main effects of prior wake and circadian phase on all PVT metrics under investigation. In general, neurobehavioral performance declined over time awake, and independent from the homeostatic influence, neurobehavioral performance exhibited a circadian rhythm with a peak during the biological day and a trough during the biological night.

In addition, consistent with previous FD studies,10,13,30 we found interactions between the homeostatic and circadian systems, as indicated by the significant prior wake × circadian phase interaction on RRT and slowest 10% RRT. The circadian oscillation of performance on these metrics became greater over time awake. This interaction, however, is not robust in that it only reached statistical significance for two out of six PVT metrics under investigation, and the P-values associated with these two significant interactions were at the borderline (0.04 and 0.05). This is in contrast to the robust prior wake × circadian phase interaction established in previous FD studies.10,13,30 Given that this interaction was found to be increasingly prominent over consecutive FD cycles,13 the difference between our and previous studies is likely due to the inclusion of a single FD cycle (i.e., 7 × 28-h day) in our study but multiple in previous studies (e.g., 36 × 28-h day13).

Compared to previous FD studies with a normal sleep-to-wake ratio, our study is different in that we imposed sleep restriction through reducing the sleep-to-wake ratio. We found that sleep restriction adversely impacted neurobehavioral function through its interactions with other factors. There was a sleep dose × FD day interaction for PVT metrics other than fastest 10% RRT and the number of false starts. Performance on these metrics declined over consecutive FD days of sleep restriction, although this decline to a certain extent reflected performance impairment due to chronic circadian misalignment during forced desynchrony regardless of imposed sleep dose.12,13 This sleep dose × FD day interaction is consistent with the cumulative effect of sleep restriction on neurobehavioral performance over consecutive days observed in previous chronic sleep restriction studies.6–8 Our study is different though, compared to these sleep restriction studies, in that it examined the impact of sleep restriction on neurobehavioral function at different combinations of prior wake and circadian phase.

We found a significant sleep dose × prior wake interaction effect on RRT SD and slowest 10% RRT. The impact of sleep restriction on these metrics was particularly pronounced at 9.5 h and 17 h awake (Figure 3A). This interaction, however, was not systematic in that the pronounced impact of sleep restriction was present at only two time points, both of which happened to be an hour after main meals (“lunch” and “dinner”). The sleep dose × prior wake interaction effects then more likely suggest that sleep restriction amplified postprandial sleepiness,31 rather than that sleep restriction accelerated performance decline over time awake. In fact, when performance data on the two metrics were fitted with a linear model, there was no significant difference in the rate of change in performance over time awake between the two sleep dose conditions.

We found a robust sleep dose × circadian phase interaction on all PVT metrics other than fastest 10% RRT. The adverse impact of sleep restriction was stronger during the biological night than it was during the biological day. This interaction indicates that the elevated homeostatic sleep pressure due to sleep restriction was amplified by the circadian sleep-promoting signals during the biological night, especially at phases shortly after the circadian nadir; this sleep pressure was, however, masked by the circadian wake-promoting signals during the biological day, especially at phases that coincide with the wake maintenance zone (Figure 3B).32 This homeostatic-circadian interaction described in terms of sleep dose × circadian phase interaction is in line with that described in terms of prior wake × circadian phase interaction, where the level of homeostatic sleep pressure is represented by prior wakefulness.10,13,30 This sleep dose × circadian phase interaction implies that previous sleep restriction studies6–8 where the impact of sleep restriction is only assessed during the biological day, likely have underestimated the extent of neurobehavioral impairment experienced by individuals who work during the biological night. Also, the masking effect of the circadian wake-promoting signals may create both safety and productivity concerns—it potentially misleads sleep restricted individuals to the belief of minimal impact of sleep restriction, and it is not until when he or she actually works during the biological night, the profound impact of sleep restriction comes to his or her full realization.

Further, we found that sleep dose × circadian phase interaction was not altered by prior wakefulness, as indicated by the absence of significant sleep dose × prior wake × circadian phase interaction for all PVT metrics. The nonsignificant 3-way interaction primarily indicates that the magnitude of the impact of sleep restriction during the biological night remained unchanged regardless of prior wakefulness (Figure 3). This once again reinforces the conclusion we drew from the sleep dose × prior wake interaction above—sleep restriction in the present study did not accelerate performance decline over time awake.

Our results regarding the performance impact of sleep dose in relation to prior wake and circadian phase partially agree with those demonstrated by Cohen and colleagues.18 The two studies are consistent in that the impact of sleep dose was prominent during the biological night. The two studies, however, differ in the impact of sleep dose in relation to prior wake. While the impact of sleep restriction in Cohen et al. was characterized by an acceleration of performance decline over time awake, in our study it was characterized by performance impairment shortly after waking (Figure 3A). This difference is not surprising, though, given that the sleep dose conditions created by the design of the two studies are qualitatively different.

Although both our study and that of Cohen et al. reduced the sleep-to-wake ratio, they are different in restricted sleep dose, day length, and study duration. While the sleep dose in the study by Cohen et al. was restricted to 10 h per 42.85-h day for three consecutive FD cycles (i.e., 12 × 42.85-h day), the sleep dose in our study was restricted to 4.7 h per 28-h day for a single FD cycle (i.e., 7 × 28-h day). Remarkably, the 10-h sleep opportunities in the study by Cohen et al. are sufficient to dissipate acute homeostatic sleep pressure, such that performance shortly after waking was not impaired despite the preceding 32.46-h wake episode. Yet the reduced sleep-to-wake ratio implicated an accumulation of chronic sleep pressure over days, such that the acceleration of performance decline over wakefulness emerged gradually over FD cycles. In contrast, the 4.76-h sleep opportunities in our study were not sufficient to dissipate acute sleep pressure, and therefore performance shortly after waking was impaired. Although the reduced sleep-to-wake ratio resulted in an accumulation of chronic sleep pressure over days (Figure 5), such pressure within the single FD cycle was constrained to implicate an apparent accelerated performance decline across wakefulness. Taken together, the performance impairment shortly after waking in our sleep-restricted protocol is underpinned by the acute homeostatic sleep process, while the acceleration of performance decline over time awake in the sleep-restricted protocol of Cohen et al. is underpinned by the chronic sleep process.

Further, these two types of performance impacts of sleep dose are dissociable. The study by Cohen et al. was the first to demonstrate a single dissociation whereby the impact of chronic sleep process was present in the absence of the impact of acute process. This dissociation provides compelling evidence for two separable mechanisms underpinning the acute and chronic sleep processes.18 Our results strengthen this theoretical position by demonstrating a single dissociation in reverse to that of Cohen—the impact of acute sleep process was present in the absence of the impact of chronic process.

Regardless of the process underlying sleep restriction, both Cohen's study18 and our study showed that neurobehavioral impairment induced by sleep restriction was in forms of escalating state instability.3,22 State instability, in its essence, is underpinned by moment-to-moment interactions whereby participants utilize increasingly greater compensatory effort to recover reduced attention caused by an elevating homeostatic drive for sleep.3,22 When sleep drive prevails, participants experience a reduced level of attention, and their responses become delayed. These delayed responses often appear as lapses (i.e., responses twice as long as response at the baseline).33 When compensatory effort prevails, participants experience a normal level of attention, and their responses remain timely. However, compensatory effort is not always effective. In particular, it may result in false starts (i.e., response in the absence of stimulus), in the sense that participants attempt to compensate for missed responses due to lapses.3,19 Consequently, the escalating state instability results in increased within-task response variability that is characterized by an intermixing of delayed and timely responses, lapses and false starts.

The escalating state instability induced by sleep restriction in our study was reflected by the increased within-task response variability, as measured by RRT SD, predominantly during the biological night. Further, the interaction between sleep drive and compensatory effort underpinning the escalating state instability is evident by (1) a differential decline in response time under sleep restriction. In the face of severe sleep restriction, slowest 10% responses increased dramatically, yet fastest 10% responses remained intact; and (2) increased incidents of lapses and false starts under sleep restriction. The escalating state instability then implies that in spite of severe sleep restriction, participants remained highly motivated to perform well such that they were constantly utilizing compensatory effort attempting to overcome the adverse impact of sleep restriction. This in turn counters the view that performance impairment, especially during vigilance tasks, under the stress of elevated sleep pressure is due to a loss of motivation.34

In summary, our novel contribution to the understanding of homeostatic-circadian regulation of neurobehavioral function is the role of sleep dose in relation to prior wake and circadian phase. We showed that the impact of sleep restriction—to a larger extent, the acute impact of sleep restriction—in forms of waking state instability, is prominent during the biological night even when the prior wake duration is short. This interaction should be reflected in mathematical models of performance and fatigue35 to provide better performance predictions and develop safer work schedules.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the reviewers for their valuable comments. The authors also thank the participants, and gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Australian Research Council.

Footnotes

A commentary on this article appears in this issue on page 829.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borbely AA. A two process model of sleep regulation. Hum Neurobiol. 1982;1:195–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daan S, Beersma DG, Borbely AA. Timing of human sleep: recovery process gated by a circadian pacemaker. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:R161–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.246.2.R161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doran SM, Van Dongen HP, Dinges DF. Sustained attention performance during sleep deprivation: evidence of state instability. Arch Ital Biol. 2001;139:253–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawson D, Reid K. Fatigue, alcohol and performance impairment. Nature. 1997;388:235. doi: 10.1038/40775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roach GD, Dawson D, Lamond N. Can a shorter psychomotor vigilance task be used as a reasonable substitute for the ten-minute psychomotor vigilance task? Chronobiol Int. 2006;23:1379–87. doi: 10.1080/07420520601067931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dinges DF, Pack F, Williams K, et al. Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4-5 hours per night. Sleep. 1997;20:267–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belenky G, Wesensten NJ, Thorne DR, et al. Patterns of performance degradation and restoration during sleep restriction and subsequent recovery: a sleep dose-response study. J Sleep Res. 2003;12:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2003.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Dongen HP, Maislin G, Mullington JM, Dinges DF. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2003;26:117–26. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czeisler CA, Buxton OM, Khalsa SBS, et al. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005. The human circadian timing system and sleep-wake regulation; pp. 375–94. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dijk D, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA. Circadian and sleep/wake dependent aspects of subjective alertness and cognitive performance. J Sleep Res. 1992;1:112–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1992.tb00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyatt JK, Ritz-De Cecco A, Czeisler CA, Dijk DJ. Circadian temperature and melatonin rhythms, sleep, and neurobehavioral function in humans living on a 20-h day. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R1152–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.4.r1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva EJ, Wang W, Ronda JM, Wyatt JK, Duffy JF. Circadian and wake-dependent influences on subjective sleepiness, cognitive throughput, and reaction time performance in older and young adults. Sleep. 2010;33:481–90. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.4.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JH, Wang W, Silva EJ, et al. Neurobehavioral performance in young adults living on a 28-h day for 6 weeks. Sleep. 2009;32:905–13. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.7.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith L, Macdonald I, Folkard S, Tucker P. Industrial shift systems. Appl Ergon. 1998;29:273–80. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(97)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roach GD, Reid KJ, Dawson D. The amount of sleep obtained by locomotive engineers: effects of break duration and time of break onset. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:e17. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.12.e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akerstedt T. Shift work and disturbed sleep/wakefulness. Sleep Med Rev. 1998;2:117–28. doi: 10.1016/s1087-0792(98)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paech GM, Jay SM, Lamond N, Roach GD, Ferguson SA. The effects of different roster schedules on sleep in miners. Appl Ergon. 2010;41:600–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen DA, Wang W, Wyatt JK, et al. Uncovering residual effects of chronic sleep loss on human performance. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:14ra3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou X, Ferguson SA, Matthews RW, et al. Dynamics of neurobehavioural performance variability under forced desynchrony: evidence of state instability. Sleep. 2011;34:57–63. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dinges DF, Powell JW. Microcomputer analyses of performance on a portable, simple visual RT task during sustained operations. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 1985;17:652–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. UCLA Brain Information Services; 1968. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques, and scoring systems for sleep stages of human subjects. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dorrian J, Rogers NL, Dinges DF. Psychomotor vigilance performance: a neurocognitive assay sensitive to sleep loss. In: Kushida CA, editor. Sleep deprivation. New York: Marcel Dekker,; 2005. pp. 39–70. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jewett ME, Wyatt JK, Ritz-De Cecco A, Khalsa SB, Dijk DJ, Czeisler CA. Time course of sleep inertia dissipation in human performance and alertness. J Sleep Res. 1999;8:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1999.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sargent C, Ferguson SA, Darwent D, Kennaway DJ, Roach GD. The influence of circadian phase and prior wake on neuromuscular function. Chronobiol Int. 2010;27:911–21. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.488901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou X, Ferguson SA, Matthews RW, et al. Interindividual differences in neurobehavioral performance in response to increasing homeostatic sleep pressure. Chronobiol Int. 2010;27:922–33. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.488958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darwent D, Ferguson SA, Sargent C, et al. Contribution of core body temperature, prior wake time, and sleep stages to cognitive throughput performance during forced desynchrony. Chronobiol Int. 2010;27:898–910. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.488621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waterhouse J, Weinert D, Minors D, et al. A comparison of some different methods for purifying core temperature data from humans. Chronobiol Int. 2000;17:539–66. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100101063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Czeisler CA, Duffy JF, Shanahan TL, et al. Stability, precision, and near-24-hour period of the human circadian pacemaker. Science. 1999;284:2177–81. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee MAM, Kleitman N. Am J Physiol. 1923. Studies on the physiology of sleep: II Attempts to demonstrate functional changes in the nervous system during experimental insomnia; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyatt JK, Cajochen C, Ritz-De Cecco A, Czeisler CA, Dijk DJ. Low-dose repeated caffeine administration for circadian-phase-dependent performance degradation during extended wakefulness. Sleep. 2004;27:374–81. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wells AS, Read NW, Idzikowski C, Jones J. Effects of meals on objective and subjective measures of daytime sleepiness. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:507–15. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strogatz SH, Kronauer RE, Czeisler CA. Circadian regulation dominates homeostatic control of sleep length and prior wake length in humans. Sleep. 1986;9:353–64. doi: 10.1093/sleep/9.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams HL, Lubin A, Goodnow JJ. Impaired performance with actue sleep loss. Psychol Monogr. 1959;73:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrison Y, Horne JA. The impact of sleep deprivation on decision making: a review. J Exp Psychol Appl. 2000;6:236–49. doi: 10.1037//1076-898x.6.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mallis MM, Mejdal S, Nguyen TT, Dinges DF. Summary of the key features of seven biomathematical models of human fatigue and performance. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2004;75:A4–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]