Abstract

Study Objectives:

To determine the incidence and risk factors for insomnia among an under-studied population of elderly persons in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Setting:

Eight contiguous predominantly Yoruba-speaking states in south-west and north-central Nigeria representing about 22% of the national population.

Participants:

1307 elderly community-dwelling persons, aged 65 years and older.

Measurements:

Face-to-face assessment with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 3 (CIDI.3) in 2007 and 12 months later in 2008 to determine the occurrence and risk factors of incident and persistent insomnia, defined as syndrome or symptom.

Results:

The incidence of insomnia syndrome in 2008 at 12 months was 7.97% (95% CI, 6.60–9.60), while that of insomnia symptom was 25.68% (22.68–28.66). Females were at elevated risk for both syndrome and symptom. Among persons with insomnia symptom or syndrome at the baseline, 47.36% (95% CI 43.07–51.68) continued to have it one year later. Decreasing economic status was associated with increasing incidence of insomnia. Persons with chronic medical conditions at baseline were at increased risk for new onset of insomnia. Compared to persons with the lowest body mass index (BMI) (< 18.5), those with higher BMI were at elevated risk for persistence of their insomnia, with those in the obese range (≥ 30) having a 4-fold risk.

Conclusions:

There is a high incidence and chronicity of insomnia in this elderly population. Persons with chronic health conditions are particularly at risk of new onset as well as persistence of insomnia.

Citation:

Gureje O; Oladeji BD; Abiona T; Makanjuola V; Esan O. The natural history of insomnia in the Ibadan Study of Ageing. SLEEP 2011;34(7):965-973.

Keywords: Epidemiology, ageing, insomnia, community dwelling, developing country

INTRODUCTION

Insomnia is a common problem among the elderly.1–3 In a previous report, we showed that at least one insomnia problem was reported by about 31% of community-dwelling elderly persons in Nigeria.4 The most common form of insomnia (24.4%) was difficultly maintaining sleep, while difficulty initiating sleep and early morning awakening had a prevalence of about 23%. Insomnia was more common among females, the unmarried, and persons aged 70 years and older.4 The public health importance of insomnia in elderly people is emphasized by several studies showing that it is associated with a range of negative health problems.5 For example, in earlier reports, we showed that insomnia was comorbid with major depressive disorder, a range of physical health problems (including heart disease and asthma), and was associated with elevated risk of falls and injury from falls.4,6

In spite of the public health significance of insomnia in the elderly, studies of its natural history are rare, with most previous longitudinal studies focusing on general adult populations.7–9 These reports suggest that incidence of insomnia could vary from 5% to 31% per year, and that between 52% and 73% of persons with insomnia would experience persistence over one year. The variations in rate seem to reflect different definitions of insomnia and whether incidence was determined in persons with no prior history of insomnia or among those who might have previous experience of the problem. For example in a study in Canada, while the incidence of insomnia symptom was 30.7% among those with a prior history of insomnia and 28.8% among those without prior history, the respective estimates of incident insomnia syndrome were 7.4% and 3.9%.10 Studies among the elderly have yielded a similar, albeit variable, pattern of high incidence and chronicity.11–13 In a study among elderly Koreans, an incidence rate of 23% was observed over 2 years among persons with no insomnia at baseline, while as many as 40% of those with insomnia continued to report the problem at follow-up.12 In an earlier study of an American cohort, a 3-year incident rate of 15% was found, and about half of the sample had persistent insomnia.13 In both studies, insomnia was defined in terms of symptoms, using the presence of any nighttime sleep problems such as difficulty falling asleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, or early morning arousal.12,13 Even though some workers have addressed the issues in the general adult populations,7,10 until now, no studies have examined the natural history of insomnia in the elderly defined in terms of both symptoms and syndrome.

Studies of insomnia in the general adult population have identified life events, health-related factors, and lifestyle features, such as smoking, as risk factors for insomnia.10,14–16 Among the elderly, widowhood, a variety of chronic health problems such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes, as well as depressive mood and poor self-perceived health have been identified as risk factors for both incidence and persistence of insomnia.13 A bi-directional relationship between insomnia and physical health problems have also been suggested, such that the presence of insomnia could lead to the emergence of physical disorders and vice-versa.12

Studies of the natural history of insomnia are important to help quantify the health burden of insomnia more accurately. Such studies will improve our understanding of the risk factors for insomnia in the elderly and throw light on factors that may be associated with its chronicity. In the report presented in this paper, we have examined the natural history of insomnia, defined in terms of symptoms and syndrome, over a 12-month period in a cohort of elderly persons taking part in a project on ageing. We present estimates of the occurrence of insomnia among persons who were good sleepers at baseline and the persistence of the problem among those who were sleeping poorly at baseline. We examine demographic and health correlates that are associated with new onset of insomnia and with its persistence.

METHODS

The methods of the baseline assessment in the Ibadan Study of Ageing (ISA) have been described in earlier reports.4,17,18 Here we provide a brief account as well as the methods of the follow-up phases.

Sample

The Ibadan Study of Ageing is a longitudinal community study of the profile and determinants of healthy ageing. Baseline assessments were conducted between August 2003 and November 2004. The study was conducted in 8 contiguous states in the southwest and north-central states of the country, states that are predominantly Yoruba-speaking. Collectively, the population of the states in 2003 was about 25 million, representing 22% of the national population. A clustered multi-stage random sampling of households was made to select a representative sample of non-institutionalized elderly persons (aged ≥ 65 years). In households with more than one eligible person, the Kish table19 was used to select one respondent. At baseline, all eligible persons who consented were recruited into the study. There were no exclusion criteria other than in cases where physical illness made interview impossible. The resulting sample size of 2152 represented a response rate of 79%. Non-response was predominantly due to change of address or not being found at home after repeated visits, rather than refusal. Three subjects who had incomplete assessment were excluded from further analysis, leaving a total of 2149.

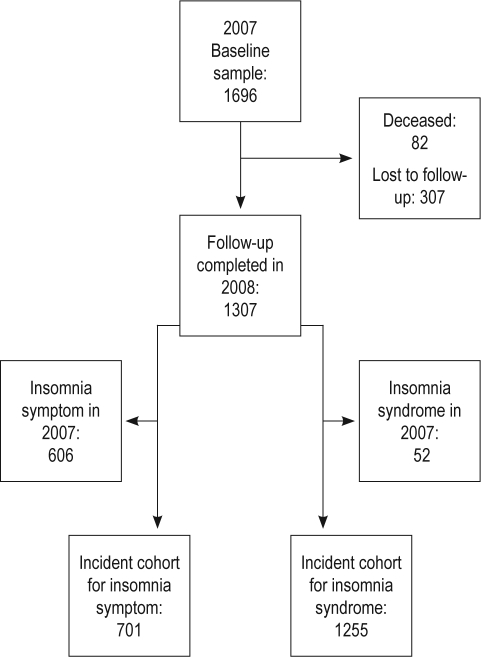

The first wave of follow-up was conducted in 2007. Of the 2149 persons successfully interviewed at baseline, 328 had died. The remaining cohort of 1821 was enlarged by the addition of 500 new sample selected from the original listing of households. The new total of 2321 constituted the study sample in 2007. Of these, 1865 (80.4%) were successfully interviewed and constitute the baseline cohort for the present report. Complete information about experience of insomnia was obtained from 1696 at baseline (Figure 1). Of these, 1307 were successfully re-evaluated at 12 months, 82 had died, and 307 were lost to follow-up or, in a few instances, refused interview.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart

Subject Assessment

Assessment of insomnia

Insomnia was assessed using the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 3 (CIDI.3), a fully structured diagnostic interview.20 The CIDI.3 asks questions about difficulty in initiating sleep (DIS), difficulty in maintaining (DMS) sleep, early morning awakening (EMA), non-restorative sleep (NRS), daytime sleepiness, and dissatisfaction with sleep. The CIDI questions, adapted as appropriate for this study, are as follows:

Difficulty initiating sleep: Did you have a period lasting two weeks or longer in the past 12 months when you had problems getting to sleep, when nearly every night it took you two hours or longer before you could fall asleep?

Difficulty maintaining sleep: Did you have a period lasting two weeks or longer in the past 12 months when you had problems staying asleep, when you woke up nearly every night and took an hour or more to get back to sleep?

Early morning awakening: Did you have a period lasting two weeks or longer in the past 12 months when you had problems waking too early, when you woke up nearly every morning at least two hours earlier than you wanted to?

Non-restorative sleep: Did you have a period lasting two weeks or longer in the past 12 months when you had difficulty getting up in the morning or when you felt not refreshed after sleeping?

Daytime sleepiness: Did you have a period lasting two weeks or longer in the past 12 months when you were feeling sleepy during the day?

Dissatisfaction with sleep: Did you have a period lasting two weeks or longer in the past 12 months when you felt you had not slept long enough even after having enough time in bed?

For every positive response, the subject was asked to indicate the duration of its occurrence.

Definition of Insomnia

We used 2 definitions of insomnia. Insomnia syndrome was assigned to persons who had at least one of DIS, DMS, EMA, or NRS, and were dissatisfied with their sleep or had daytime sleepiness lasting for ≥ 4 weeks. This definition was used to approximate the diagnosis of insomnia based on the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).21 Insomnia symptom was said to be present when a respondent endorsed any one of the 4 nighttime sleep problems (DIS, DMS, EMA, or NRS) almost every night for ≥ 2 weeks.

Risk Factor Assessment: Tools and Ascertainment Procedures

Variables assessed at baseline (2007) were used to explore risk factors for incidence and persistence. Depression was assessed using the CIDI.3.22 Diagnosis of lifetime major depressive disorder (MDD) was based on the criteria of the DSM-IV. The DSM-IV organic exclusion rules were imposed in making the diagnosis of depression. Judgments about which organic conditions could explain a co-occurring MDD was made during clinical reviews (by a psychiatrist) of all questionnaires in which endorsements of depressive features were made.

Dementia was assessed with the use of 2 previously validated cognitive assessment tools, one for screening and the other for the evaluation of cognitive and functional capacities. Screening was done with the 10-Word Delayed Recall Test. The 10-WDRT, adapted from the Consortium to Establish a Registry of Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD) 10-word learning list, is a test of memory.23 The 10-WDRT has been shown to be a valid tool for the assessment of dementia in Nigerian subjects.24 The evaluation of functional capacity was done with the Clinician Home-based Interview to assess Function (CHIF).25 The CHIF was developed by our group to provide a reliable assessment of cognitive function in elderly subjects. The CHIF is a 10-item semi-structured home interview schedule that evaluates respondent's higher cognitive function by assessing their knowledge of how to perform instrumental activities of daily living (irrespective of whether they are physically capable of actually performing the activities). A diagnosis of dementia was made following a review of all available information by a psychiatrist. The information included scores on the 10-WDRT (< 2) and CHIF (< 18), interviewer's observations (of respondent's memory and language), reported functional status (commonly supplemented by key informant's report), as well as the temporal relationship of the onset of any co-occurring depressive disorder

A checklist of chronic physical and pain conditions was completed.26 Respondents were asked if they had arthrits, stroke, diabetes, chronic lung disease, hypertension, or cancer. Respondents were asked whether they had experienced each of the symptom-based conditions in the previous 12 months. Even though we do not have data on the validity of reports based on the checklist in this sample, such checklists have been shown to provide more complete and accurate reports than estimates derived from responses to open-ended questions27 and to have moderate to good concordance with medical records.28

We determined the presence of functional limitations in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.29–31 Each of the activities in the 2 domains was rated as follows: (1) can do without difficulty, (2) can do with some difficulty, (3) can do only with assistance, or (4) unable to do. In this report, any respondent with a rating of 3 or 4 on any item was classified as disabled.

A history of the occurrence of life events in the 12 months prior to the baseline assessment was obtained with the use of the List of Threatening Experiences (LTE).32 The LTE is a brief inventory of live events with particular relevance to studies in which intervening factors such as social support and network are of interest. (Even though we also assessed the experience of LTE during the 12 months preceding the follow-up, the results are not presented here, as we do not have sufficient information to determine the temporal relations between the events in that period to the occurrence of insomnia also during the period). Social network was assessed with items from the CIDI.22 The relevant items enquire about the frequency of respondent's contact with family members who do not live with the respondent and frequency of contact with friends. In this report, we have dichotomized the responses to no contacts at all versus contacts varying from < 1/month to daily.

Every respondent had measure of their height and weight taken. We determined the body mass index (BMI) using the formula weight in kilograms over height squared (m2). We categorized the resulting values as obese (BMI ≥ 30.0), overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9), normal (BMI 18.5-24.9), or underweight (BMI ≤ 18.5).

Economic status was assessed by taking an inventory of household and personal items such as chairs, clock, bucket, radio, television set, fans, stove or cooker, car, telephone, etc. The list was composed of 21 such items. This is a standard and validated method of estimating economic wealth of elderly persons in low-income settings.33 Respondents' economic status was categorized by relating each respondent's total possessions to the median number of possessions of the entire sample. Economic status was rated low if its ratio to the median was ≤ 0.5, low-average if the ratio was 0.5-1.0, high-average if it was 1.0-2.0, and high if it was > 2.0. Residence was classified as rural (< 12,000 households), semi-urban (12,000–20,000 households), or urban (> 20,000 households).

Assessment, Training, and Quality Control

All interviews were conducted in respondents' homes. The interviews at the baseline were conducted by 24 trained interviewers, all of whom had at least a high school education. Training lasted one week and consisted of role plays, trial interviews, and debriefing sessions. During field work, a supervisor, who had undergone the same level of training, monitored the day-to-day implementation of the survey. The research supervisor was responsible for the work of 4 interviewers and checked every questionnaire returned by those interviewers for completeness and consistency. He or she made random field checks on ≥ 10% of each interviewer's respondents (more at the beginning of the survey) to ensure the correct implementation of the protocol and full adherence to interview format. Special emphasis was placed on the detection of systematic errors or bias in the administration of the interview. Following these interviews, a second assessment was conducted within 2 days by the supervisors, during which several other ratings, including measures of weight and height were made. During the fieldwork, regular debriefing sessions were held when all interviewers and supervisors returned to the central office for review of field work procedure and experience.

The ISA was approved by the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital, Ibadan Joint Ethical Review Board.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to compare persons who were successfully followed up in 2008 with those who had died and those who could not be interviewed for other reasons.

Incident insomnia symptom was determined in persons who, in 2007, reported no experience of any nighttime sleep problem but who, in 2008, reported the presence of at least one nighttime problem. Incident insomnia syndrome was determined in persons who, in 2007, did not have insomnia syndrome but who had, in 2008, met the criteria for insomnia syndrome. Persistent insomnia was determined among persons with insomnia (symptom or syndrome) in 2007 and who continued to have either insomnia symptom or syndrome in 2008. Thus, persons who reported either an insomnia symptom or who met the criteria for insomnia syndrome at anytime in the 12 months leading to their assessment in 2007 constituted the sample for the analysis of persistent insomnia in 2008. A person who had insomnia symptoms (but not syndrome) at baseline and who developed insomnia syndrome at follow-up was regarded as an incident case of insomnia syndrome as well as a case of persistent insomnia.

Logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the factors associated with incidence and with persistence.34 These analyses took account of the complex selection procedure of the respondents. The estimates of the confidence intervals of odds ratios are adjusted for design effects. Thus, we used the jackknife replication method implemented with the STATA statistical package to estimate standard errors for proportions. All the statistical tests were done with the STATA statistical package.35

RESULTS

The total sample in 2007 was 1696, consisting of 977 (50.5%) females and 719 (49.6%) males. Persons aged between 70 and 74 years constituted the largest group (31.0%). There were more urban (37.8%) than semi-urban (33.6%) and rural (28.6%) residents. Table 1 shows the results of the comparisons of the group that was successfully followed up with those that were either dead or could not otherwise be interviewed at the 2008 follow-up. Demographic factors were related to status at follow-up. More females than males were either dead or lost at follow-up. As expected, more persons in the oldest age group were dead at follow-up. Economic group was also related to status at follow-up. Thus, while persons in the high average or high economic groups constituted 29% of survivors who were successfully interviewed, they constituted 41.5% of those who were dead and 35.5% of those who were lost to follow-up.

Table 1.

Profile of the sample at follow-up

| Total (1696) | Successfully interviewed (1307) | Deceased (82) | Lost to follow-up (307) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted N (%) | Weighted N (%) | Weighted N (%) | Weighted N (%) | P value | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 977 (50.5) | 742 (47.5) | 46 (56.1) | 189 (61.6) | 0.001 |

| Male | 719 (49.6) | 565 (52.5) | 36 (43.9) | 118 (38.4) | |

| Age group | |||||

| 65-69 | 297 (18.9) | 222 (18.8) | 9 (11.0) | 66 (21.5) | 0.001 |

| 70-74 | 477 (31.0) | 367 (31.8) | 22 (26.8) | 88 (28.7) | |

| 75-79 | 328 (21.3) | 265 (22.8) | 11 (13.4) | 52 (16.9) | |

| 80+ | 594 (28.9) | 453 (26.7) | 40 (48.8) | 101 (32.9) | |

| Site | |||||

| Urban | 642 (37.8) | 468 (35.7) | 38 (46.3) | 136 (44.3) | 0.046 |

| Semi-Urban | 576 (33.6) | 452 (34.2) | 23 (28.1) | 101 (32.9) | |

| Rural | 478 (28.6) | 387 (30.1) | 21 (25.6) | 70 (22.8) | |

| Economic group | |||||

| Low | 649 (36.1) | 512 (36.4) | 25 (30.5) | 112 (36.5) | 0.001 |

| Low average | 521 (33.2) | 412 (34.7) | 23 (28.1) | 86 (28.0) | |

| High average | 384 (20.4) | 271 (17.9) | 29 (35.4) | 84 (27.4) | |

| High | 142 (10.3) | 112 (11.1) | 5 (6.1) | 25 (8.1) |

Incident Insomnia (Table 2)

Table 2.

Profile of incident insomnia

| Total, N | Insomnia, n | Incidence insomnia % (95% CI) | Relative Risk (95% CI) | Relative Risk P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | |||||

| Total | 701 | 180 | 25.68 (22.91-28.66) | ||

| Male | 312 | 66 | 21.15 (18.05-24.63) | 1 | - |

| Female | 389 | 114 | 29.31 (25.16-33.83) | 1.44 (1.10-1.88) | 0.008 |

| Age Group | |||||

| 65-69 | 136 | 30 | 22.06 (16.95-28.19) | 1 | - |

| 70-74 | 199 | 49 | 24.62 (18.77-31.6) | 1.14 (0.77-1.70) | 0.505 |

| 75-79 | 152 | 46 | 30.26 (34.37-36.89) | 1.47 (0.99-2.19) | 0.058 |

| 80+ | 214 | 55 | 25.70 (20.52-31.67) | 1.17 (0.80-1.73) | 0.419 |

| Syndrome | |||||

| Total | 1255 | 100 | 7.97 (6.60-9.60) | ||

| Male | 712 | 31 | 5.71 (4.02-8.05) | 1 | - |

| Female | 543 | 69 | 9.69 (7.31-11.96 | 1.69 (1.12-2.57) | 0.013 |

| Age Group | |||||

| 65-69 | 217 | 17 | 7.83 (4.61-13.01) | - | - |

| 70-74 | 347 | 25 | 7.21 (4.84-10.59) | 0.97 (0.54-1.76) | 0.925 |

| 75-79 | 258 | 20 | 7.75 (5.03-11.77) | 1.09 (0.58-2.03) | 0.792 |

| 80+ | 433 | 38 | 8.78 (6.49-11.77) | 1.13 (0.66-1.96) | 0.654 |

Insomnia symptoms

Among the total incident cohort of 701 persons with no insomnia symptoms at baseline (2007), 180 had experienced a new onset of insomnia symptoms 12 months later. Females had a higher incidence of insomnia symptoms than males, with a relative risk of 1.44 (95% CI 1.10–1.88; P = 0.008). Rates of incident insomnia symptoms did not differ between the age groups.

Insomnia syndrome

A total of 1255 persons with no insomnia syndrome in 2007 formed the incident cohort for incident syndrome in 2008. Of these, 100 persons had developed a new onset of insomnia syndrome in 2008, representing an incidence rate of 7.97% (95% CI, 6.60–9.60) in the 12-month period. Females had higher rate than males (9.69%, 95% CI 7.31–11.96 versus 5.71%, 95% CI 4.02–8.05). Compared to males, the relative risk for females was 1.69 (95% CI 1.12–2.57; P < 0.013). There were no differences in rates between the age groups.

Persistent Insomnia (Table 3)

Table 3.

Profile of persistent insomnia

| Total, N | Insomnia, n | Persistence Insomnia % (95% CI) | Relative Risk (95% CI) | Relative Risk P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 606 | 287 | 47.36 (43.07-51.68) | ||

| Male | 253 | 114 | 45.06 (38.57-51.72) | 1 | - |

| Female | 353 | 173 | 49.01 (43.77-54.27) | 1.09 (0.92-1.30) | 0.328 |

| Age Group | |||||

| 65-69 | 86 | 45 | 52.33 (40.67-63.74) | 1 | - |

| 70-74 | 168 | 82 | 48.81 (43.04-54.61) | 0.95 (0.73-1.22) | 0.680 |

| 75-79 | 113 | 53 | 46.90 (38.96-55.01) | 0.91 (0.69-1.21) | 0.524 |

| 80+ | 239 | 107 | 44.77 (36.98-52.82) | 0.86 (0.67-1.10) | 0.226 |

Only 52 persons met criteria for insomnia syndrome at baseline. Of these, 6 (11.5%) continued to meet the criteria in 2008, while 46 had insomnia symptom. Neither sex nor age differentiated the 6 from the 46. Insomnia syndrome was persistent in 18% (4 of 22) of men and 6.7% (2 of 30) of women. The 6 persons in whom the syndrome was persistent were aged 79.3 years (SD 3.3), compared to the 46 in whom it was not who were aged 77.4 years (SD 1.2). In order to increase the power of the analysis, persistent insomnia was estimated among persons who had either syndrome or symptoms at baseline and continued to have either syndrome or symptoms at follow-up.

Of the 606 persons with insomnia symptom or syndrome at baseline, 287 (47.36%, 95% CI 43.07–51.68) continued to report insomnia symptoms or syndrome in 2008. Persistence was unrelated either to gender or to age.

Baseline Risk Factors for Incident Insomnia

In analysis that adjusted for age and sex, essentially similar baseline factors were associated with the emergence of new onset of insomnia symptom or syndrome (Table 4). However, while there was significant trend for decreasing economic status to be a risk factor for incident insomnia syndrome (in which, compared to persons in the high economic group, elevated risks were observed for persons in the high average (odds ratio 2.9), low average (OR 4.5), and low (OR 4.9) groups), no such trend was observed for insomnia symptom. The presence of self-reported chronic physical condition at baseline was a risk factor for new onset of both insomnia syndrome and insomnia symptom, associated with almost 3-fold increase in both. None of the following was a significant predictor of incident insomnia or insomnia syndrome: residence, lifetime history of major depressive disorder, presence of disability, self-rated overall health, or the experience of threatening life event 12 months prior to the baseline assessment (result not shown in table).

Table 4.

Baseline risk factors for incident insomnia

| Insomnia Symptom |

Insomnia Syndrome |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR* | 95% CI | P-value | n (%) | OR* | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 407 (67.0) | 1 | - | - | 704 (65.3) | 1 | - | - |

| Widowed or divorced | 294 (33.0) | 1.2 | 0.8-1.7 | 0.464 | 551 (34.7) | 1.2 | 0.7-2.2 | 0.471 |

| Residence | ||||||||

| Urban | 241 (34.8) | 1 | - | - | 448 (35.7) | 1 | - | - |

| Semi Urban | 241 (33.79) | 1.4 | 0.5-4.3 | 0.501 | 432 (34.0) | 1.4 | 0.9-2.3 | 0.119 |

| Rural | 219 (31.43) | 1.2 | 0.4-3.8 | 0.642 | 375 (30.3) | 1.5 | 0.9-2.4 | 0.099 |

| Economic status | ||||||||

| High | 72 (12.4) | 1 | - | - | 109 (10.9) | 1 | - | - |

| High average | 226 (35.8) | 1.4 | 0.6-3.0 | 0.432 | 398 (35.2) | 2.9 | 0.8-10.2 | 0.087 |

| Low average | 279 (36.5) | 1.4 | 0.6-3.5 | 0.406 | 495 (36.7) | 4.5 | 1.2-16.6 | 0.026* |

| Low | 124 (15.3) | 1.4 | 0.5-3.8 | 0.464 | 253 (17.3) | 4.9 | 1.0-24.1 | 0.049* |

| Self-reported health | ||||||||

| Poor or fair | 5 (0.6) | 1 | - | - | 25 (2.2) | 1 | - | - |

| Excellent or Good | 690 (99.4) | 0.8 | 0.1-6.7 | 0.869 | 1214 (97.8) | 0.2 | 0.1-1.1 | 0.058 |

| Body mass index | ||||||||

| < 18.5 | 110 (16.7) | 1 | - | - | 185 (16.5) | 1 | - | - |

| 18.5-24.9 | 361 (59.1) | 1.5 | 0.8-2.6 | 0.179 | 648 (59.8) | 1.6 | 0.7-3.8 | 0.288 |

| 25.0-29.9 | 104 (17.8) | 0.9 | 0.3-2.7 | 0.807 | 192 (17.6) | 1.4 | 0.5-4.1 | 0.525 |

| ≥ 30 | 37 (6.4) | 1.7 | 0.5-6.0 | 0.432 | 67 (6.1) | 1.8 | 0.5-6.8 | 0.348 |

| Chronic medical condition | ||||||||

| Absent | 228 (34.4) | 1 | - | - | 319 (26.4) | 1 | - | - |

| Present | 473 (65.6) | 2.6 | 1.6-4.2 | 0.001* | 936 (73.6) | 2.9 | 1.4-6.2 | 0.007* |

| Functional disability | ||||||||

| Absent | 596 (87.9) | 1 | - | 989 (82.1) | 1 | - | - | |

| Present | 105 (12.1) | 1.2 | 0.8-1.8 | 0.427 | 266 (17.9) | 1.5 | 0.7-3.2 | 0.284 |

| Lifetime major depression | ||||||||

| Absent | 477 (70.2) | 1 | - | 826 (67.6) | 1 | - | - | |

| Present | 224 (29.8) | 1.5 | 0.9-2.5 | 0.096 | 429 (32.4) | 1.5 | 0.9-2.4 | 0.101 |

| Probable dementia | ||||||||

| Absent | 636 (94.0) | 1 | - | 1131 (93.2) | 1 | - | - | |

| Present | 48 (6.0) | 0.9 | 0.4-2.1 | 0.793 | 101 (6.8) | 1.0 | 0.3-2.8 | 0.952 |

Baseline Risk Factor for Persistent Insomnia

Of all the baseline factors examined, only BMI was related to persistence of insomnia (Table 5). Compared to persons with BMI < 18.5, there was a trend for persons with higher BMI status to be more likely to have persistent insomnia, with those with BMI ≥ 30 having an almost 4-fold increased risk. No other factors were found to predict the persistence of insomnia at follow-up.

Table 5.

Risk factors for persistent insomnia

| Persistence Symptom/Syndrome |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR* | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 319 (62.2) | 1 | - | - |

| Widowed or divorced | 287 (37.8) | 1.3 | 0.8-2.0 | 0.258 |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 227 (36.8) | 1 | - | - |

| Semi Urban | 211 (34.6) | 1.0 | 0.5-1.9 | 0.975 |

| Rural | 168 (28.5) | 0.7 | 0.5-1.1 | 0.161 |

| Economic status | ||||

| High | 40 (9.3) | 1 | - | - |

| High average | 185 (33.2) | 0.6 | 0.3-1.5 | 0.276 |

| Low average | 234 (36.4) | 0.9 | 0.4-1.9 | 0.824 |

| Low | 147 (21.1) | 0.9 | 0.4-2.2 | 0.786 |

| Self-reported health | ||||

| Poor or fair | 33 (6.1) | 1 | - | - |

| Excellent or good | 562 (93.9) | 0.5 | 0.2-1.4 | 0.186 |

| Body mass index | ||||

| < 18.5 | 82 (15.4) | 1 | - | - |

| 18.5-24.9 | 315 (62.4) | 2.0 | 0.9-4.3 | 0.076 |

| 25.0-29.9 | 93 (16.5) | 1.4 | 0.6-3.0 | 0.832 |

| ≥ 30 | 35 (5.7) | 2.2 | 0.7-6.6 | 0.161 |

| Chronic medical condition | ||||

| Absent | 92 (14.2) | 1 | - | - |

| Present | 514 (85.8) | 1.2 | 0.6-2.1 | 0.635 |

| Functional disability | ||||

| Absent | 427 (73.8) | 1 | - | - |

| Present | 179 (26.2) | 1.2 | 0.8-1.7 | 0.448 |

| Lifetime major depression | ||||

| Absent | 373 (61.9) | 1 | - | - |

| Present | 233 (38.1) | 1.2 | 0.8-1.7 | 0.362 |

| Probable dementia | ||||

| Absent | 543 (92.8) | 1 | - | - |

| Present | 56 (7.2) | 0.6 | 0.3-1.2 | 0.160 |

DISCUSSION

In this study of community-dwelling elderly persons, we have found a 12-month incidence of about 8% for insomnia syndrome and 26% for insomnia symptoms. Females had significantly higher incidence rates of both definitions of insomnia than males. We did not find an association with increasing age. Among persons with insomnia at baseline, about 50% continued to have the condition 12 months later. Neither gender nor age was a significant factor for persistence of insomnia. In general, while it was possible to identify some predictive factors for incidence of insomnia, persistence was more difficult to predict from baseline factors. There was a clear trend for the risk of incident insomnia to increase with decreasing economic status, but this trend was only significant for insomnia syndrome. Among health conditions, persons with chronic physical conditions at baseline had elevated risk for incident insomnia. No other social or health-related variables constituted significant risk factors for incident insomnia. On the other hand, increasing BMI was associated with a higher risk for insomnia to be persistent at follow-up.

In considering the results of our study, its strengths as well as weaknesses need to be borne in mind. One of the strengths is that we have studied a well-defined and large cohort of elderly persons. We believe that the size of the sample would have produced a set of stable estimates of incidence and persistence of insomnia. Another strength is that the assessments were conducted during face-to-face direct interviews by well-trained interviewers, rather than by the use of telephone interviews or postal questionnaire survey. A weakness of the study is its reliance on self-report for most of the measures, especially for the assessment of insomnia. This is however the usual method of ascertaining insomnia, especially when items that are entirely subjectively experienced, such as sleep dissatisfaction and non-restorative sleep, are included in its definition. Nevertheless, the use of self-report for the presence of chronic medical conditions may have been affected by false negatives in instances when persons with conditions such as diabetes and hypertension were not aware of being so afflicted. To the extent that such false negatives existed, however, our results would have been conservative rather than otherwise. Attrition in this cohort sample was not random. Thus, we found that demographic factors, in particular age and sex, were associated with attrition. This observation may have affected the generalizability of the findings to the entire baseline sample and by, extension, the population from which that sample was drawn. We did however control for these factors in our exploration of risk factors.

In comparing the results of our study with those of earlier reports, due cognizance must be taken of differences in the definitions of insomnia that have been used. Thus, for example, while we used a duration of 2 weeks to define the presence of insomnia, some others have used a 4-week cut-off.12 On the other hand, we chose to use the criterion of 2 hours to fall asleep, rather than 30 minutes as often used in younger adults, in order to reduce false positives and improve the validity of our definition of insomnia in this age group. Also, we have not included an assessment of daytime functioning in the definition of insomnia syndrome as has been used in other reports.36 Rather, we have used the criterion of daytime sleepiness. In this elderly population with little routine daytime role functioning, we were convinced that daytime sleepiness was a better index of the impact of insomnia.

Previous studies of incident insomnia in the elderly have generally used the presence of one of the nighttime sleep problems, DIS, DMS, or EMA.12,13 These studies can be seen as approximating our definition of insomnia symptom, even though we have also included non-restorative sleep in our definition of insomnia symptom. Using these previous studies as the basis for comparison, the rate we have reported in this paper is considerably higher. For example, Foley et al. reported an annual incidence rate of approximately 5% among their sample of elderly persons aged 65 years and older.13 In a study conducted among elderly Koreans, Kim et al. reported an incidence rate of 23% over a period of two years, or an annualized rate of approximately 11.5%.12 Our higher rate of 26% for incident insomnia may reflect the broader definition of insomnia symptoms that we have used. While we used a duration of 2 weeks, Kim and colleagues used 4 weeks. However, it may also reflect a particularly higher rate of insomnia in this group of elderly Africans. In a report of biracial differences in incident insomnia, Foley et al. found African American women to have a significantly higher rate than African American men and white men and women.37 Irrespective of the basis for this higher vulnerability, our findings suggest, to the extent that insomnia is commonly a manifestation of psychological distress, a high burden of such distress in this population of elderly persons. It is in consonance with the high level of depression that we have previously reported in the sample.38

The incidence rate of about 26% reported here for insomnia symptoms is very close to the prevalence rate of 31% reported earlier by us in this cohort.4 This observation suggests a pattern of waxing and waning of the symptoms such that, at any given time, about the same proportion of the population has the problem. This observation is reinforced by the observation that, of the 52 persons with insomnia syndrome in 2007, only 6 met the same criteria at follow-up in 2008, while 42 had insomnia symptoms. In general, we found that insomnia syndrome is a much less common condition, the rate of incident syndrome being about a quarter of that of symptoms. Studies among general adult populations have found the incidence of syndrome to be much less than that of symptoms.7,10 We suspect that, while there may be difference in degree or severity, both conditions probably carry similar consequences in regard to their impact on sufferers. Whatever may be their consequences, we found that similar factors constitute risks for the development of symptoms as do for syndrome. In this regard the much higher rates in women than in men is similar to findings by others.10 Also, the salience of chronic physical conditions for the emergence of new onset of insomnia is in consonance with common findings among elderly persons.5,39 Indeed, it has been speculated that the higher rate among black women probably reflects their vulnerability to higher rates of the predisposing health conditions.37 However, our exploration of risk factors did control for sex for precisely these reasons. Our finding of an elevated likelihood of insomnia among persons with chronic physical conditions, even after the effect of sex was controlled for, suggests that these health conditions constitute risks for both men and women.

Among those with insomnia (symptoms or syndrome) at baseline, 47% continued to have insomnia at follow-up one year later, while remission had occurred in the remaining 53%. Over a three-year period, Foley et al. found a remission rate of about 50% in their sample of elderly persons.13 Comparatively therefore, it would appear that remission was more likely in our sample. However, given that we have documented the occurrence of insomnia over a 12-month period prior to each assessment, it is quite likely that a substantial proportion of persons classified as having persistent insomnia actually had recurring problems, with symptoms coming and going over the period. Our findings are in conformity with those of studies among general adult populations in showing a high rate of persistence of insomnia.7

We found only one correlate of persistence. Compared with persons with the lowest BMI, those with higher BMI were at elevated risk for persistence of their insomnia with those in the obese range being at the highest risk. Even though there was a suggestive trend increasing BMI to be associated with higher incidence rates, the trend did not achieve significance. Nevertheless, the associations that we found are in consonance with expectation as overweight and obesity are risk factors for sleep problems. One important factor that would have been interesting to know how it was related to persistence was use of medication, especially sleeping pills. Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain reliable data on this, as the common trend was for all sorts of medication to be obtained across the counter, often in unlabelled packages and therefore difficult to indentify. The most commonly used sleeping pill in Nigeria, diazepam, has only recently become controlled in its prescription and sale. A similar measure is yet to be applied to other hypnosedatives or psychoactive medications.

We have earlier shown that the considerable decrement in quality of life associated with insomnia is only partly but not entirely explained by the comorbid physical and mental conditions often present among sufferers.4 We now show in this paper that these conditions may also be precursors for onset of insomnia. The high incidence of insomnia that we have reported may reflect a high burden of these physical and mental conditions in our sample and further draws attention to the public health importance of insomnia in this population. In exploring the natural history of insomnia further, it would be interesting for future research to also explore the relationship of changes in the evolution of the risk factors (e.g. BMI, life events) to the incidence and the persistence of insomnia.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Ibadan Study of Ageing is funded by the Wellcome Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1.Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Brown SL, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB, Blazer DG. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep. 1995;18:425–32. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.6.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Dalton DS, Klein BE, Klein R. Prevalence of sleep problems and quality of life in an older population. Sleep. 2002;25:889–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sukying C, Bhokakul V, Udomsubpayakul U. An epidemiological study on insomnia in an elderly Thai population. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003;86:316–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gureje O, Kola L, Ademola A, Olley BO. Profile, comorbidity and impact of insomnia in the Ibadan Study of Ageing. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:686–93. doi: 10.1002/gps.2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, Walsh J. Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. Psychosom Res. 2004;56:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekibele CO, Gureje O. Fall incidence in a population of elderly persons in Nigeria. Gerontology. 2010;56:278–83. doi: 10.1159/000236327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morin CM, Belanger L, LeBlanc M, et al. The natural history of insomnia: a population-based 3-year longitudinal study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:447–53. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morphy H, Dunn KM, Lewis M, Boardman HF, Croft PR. Epidemiology of insomnia: a longitudinal study in a UK population. Sleep. 2007;30:274–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansson-Frojmark M, Linton SJ. The course of insomnia over one year: a longitudinal study in the General Population in Sweden. Sleep. 2008;31:881–86. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.6.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LeBlanc M, Merette C, Savard J, Ivers H, Baillargeon L, Morin CM. Incidence and risk factors of insomnia in a population-based sample. Sleep. 2009;32:1027–37. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.8.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganguli M, Reynolds CF, Gilby JE. Prevalence and persistence of sleep complaints in a rural older community sample: the MOVIES Project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:778–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb03733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim JM, Stewart R, Kim SW, Yang SJ, Shin IS, Yoon JS. Insomnia, depression, and physical disorders in late life: a 2-year longitudinal community study in Koreans. Sleep. 2009;32:1221–28. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.9.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foley DJ, Monjan A, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB, Blazer DG. Incidence and remission of insomnia among elderly adults: an epidemiologic study of 6,800 persons over three years. Sleep. 1999;22:S366–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Healy ES, Kales A, Monroe LJ, et al. Onset of insomnia: role of life-stress events. Psychosom Med. 1981;43:439–51. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Precipitating factors of insomnia. Behav Sleep Med. 2004;2:50–62. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0201_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips BA, Danner FK. Cigarette smoking and sleep disturbance. Arch Intern Med. 1995;10:734–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gureje O, Kola L, Afolabi E. Epidemiology of major depressive illness in the Ibadan Study of Aging. Lancet. 2007;370:957–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61446-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gureje O, Ogunniyi A, Kola L, Afolabi E. Functional disability among elderly Nigerians: results from the Ibadan Study of Aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1784–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00944.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kish L. Survey sampling. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welsh KA, Butters N, Mohs RC, et al. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease (CERAD): V-a normative study of the neuropsychological battery. Neurology. 1994;44:609–14. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.4.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prince M, Acosta D, Chiu H, Scazufca M, Varghese M. Dementia diagnosis in developing countries: a cross-cultural validation study. Lancet. 2003;361:909–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12772-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendrie HC, Lane KA, Ogunniyi A, et al. The development of a semi-structured home interview (CHIF) to directly assess function in cognitively impaired elderly people in two cultures. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18:653–66. doi: 10.1017/S104161020500308X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health. United States: Center for Disease Control; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knight M, Stewart-Brown S, Fletcher L. Estimating health needs: the impact of a checklist of conditions and quality of life measurement on health information derived from community surveys. J Public Health Med. 2001;23:179–86. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/23.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker M, Stabile M, Deri C. What do self-reported, objective, measures of health measure? J Human Resources. 2001;39:1067–93. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagi SZ. An epidemiology of disability among adults in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1976;54:439–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz S, Akpom CA. A measure of primary sociobiological functions. Int J Health Services. 1976;6:493–508. doi: 10.2190/UURL-2RYU-WRYD-EY3K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brugha T, Bebbington P, Tennant C, Hurry J. The list of threatening experiences: a subset of 12 life event categories with considerable long-term threat. Psychol Med. 1985;15:189–94. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002105x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferguson BD, Tandon A, Gakidou E, Murray CJL. Estimating permanent income using indicator variables. In: Murray CJ, Evans D, editors. Health Systems Performance Assessment: Debates, Methods and Empiricism. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. pp. 747–760. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software 7.0 for windows. College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morin CM, Colecchi C, Stone J, Sood R, Brink D. Behavioural and pharmacological therapies for late-life insomnia. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;281:991–99. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.11.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Izmirlian G, Hays JC, Blazer DG. Incidence and remission of insomnia among elderly adults in a biracial cohort. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl. 2):S373–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gureje O, Kola L, Afolabi E. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder in elderly Nigerians in the Ibadan Study of Ageing: a community-based survey. Lancet. 2007;370:957–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61446-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paudel ML, Taylor BC, Diem SJ, et al. Association between depressive symptoms and sleep disturbances in community-dwelling older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1228–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]