Abstract

Background

We previously reported an increased risk of all-cause and AIDS mortality among HIV-infected women with albuminuria (proteinuria or microalbuminuria) enrolled in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) prior to the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).

Methods

The current analysis includes 1,073 WIHS participants who subsequently initiated HAART. Urinalysis for proteinuria and semi-quantitative testing for microalbuminuria from two consecutive study visits prior to HAART initiation were categorized as follows: confirmed proteinuria (both specimens positive for protein), confirmed microalbuminuria (both specimens positive with at least one microalbuminuria), unconfirmed albuminuria (one specimen positive for proteinuria or microalbuminuria), or negative (both specimens negative). Time from HAART initiation to death was modeled using proportional hazards analysis.

Results

Compared to the reference group of women with two negative specimens, the hazard ratio (HR) for all-cause mortality was significantly elevated for women with confirmed microalbuminuria (HR 1.9; 95% CI 1.2–2.9). Confirmed microalbuminuria was also independently associated with AIDS death (HR 2.3; 95% CI 1.3–4.3), while women with confirmed proteinuria were at increased risk for non-AIDS death (HR 2.4; 95% CI 1.2–4.6).

Conclusions

In women initiating HAART, pre-existing microalbuminuria independently predicted increased AIDS mortality, while pre-existing proteinuria predicted increased risk of non-AIDS death. Urine testing may identify HIV-infected individuals at increased risk for mortality even after the initiation of HAART. Future studies should consider whether these widely available tests can identify individuals who would benefit from more aggressive management of HIV infection and comorbid conditions associated with mortality in this population.

Keywords: HIV, microalbuminuria, proteinuria, mortality, non-AIDS death

Microalbuminuria is prevalent among HIV-infected individuals [1] [2] [3] and predicts mortality in other high-risk populations.[4] We have previously reported that prior to the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART),[5] HIV-infected women with proteinuria or microalbuminuria had an increased risk of all-cause and AIDS-related mortality. The current analysis investigates whether pre-existing microalbuminuria also predicts mortality among HIV-infected women who initiate HAART.

Methods

The Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) has been described. [6] HIV-infected and high-risk seronegative women were enrolled from six United States sites. Social and medical history, HIV-RNA, CD4, hemoglobin, serum albumin, and urinalysis were ascertained at enrollment and every six months. Hepatitis serologies and serum creatinine were performed at enrollment, and creatinine was repeated annually. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated using the 4-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation.[7] The institutional review board of each site approved the WIHS protocol, and participants provided written informed consent.

Urine specimens were collected every 6 months for the first 3 years and stored at −70°C in a central repository. Specimens were excluded if there was evidence of cystitis, as previously described. [5] Semi-quantitative microalbuminuria testing (Clinitek Microalbumin Reagent Strips and Clinitek 50 Analyzer, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL) was performed in banked specimens from the first two eligible visits for each participant. Quality assurance testing was performed using standardized controls (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Microalbuminuria was defined as an albumin: creatinine ratio > 30 mg/g (3.4 mg/mmol). Women with urinalysis protein ≥1+ at both visits were considered to have “confirmed proteinuria.” Women with microalbuminuria at both visits or with microalbuminuria at one visit and proteinuria at the other were considered to have “confirmed microalbuminuria.” Women with proteinuria or microalbuminuria at only one visit were considered to have “unconfirmed albuminuria.” This analysis excluded women who initiated HAART prior to the second urine visit. Among included participants, the median time from the second urine visit to HAART initiation was 728 days.

Data on vital status and date of death were collected from medical records, providers, personal contacts, and the National Death Index. Cause of death was ascertained from the death certificate, medical records, providers, or personal contacts, in that order, and categorized as AIDS or non-AIDS using previously described methods. [8]

HIV-infected women enrolled in 1994–1995 who subsequently initiated HAART were included in this analysis. Sustained HAART use was defined as self-reported use for ≥ 3 consecutive visits prior to March 2009. The date of HAART initiation was defined as the mid-point between the last pre-HAART visit and the first visit at which HAART use was reported. Women with > 2 missed visits between the last pre-HAART visit and the first HAART visit were excluded. Continuous and categorical variables were compared by level of albuminuria using Kruskal-Wallis and chi-square tests, respectively. A 2-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Kaplan-Meier and proportional hazards models evaluated the association of albuminuria with time from HAART initiation to death. Multivariate models adjusted for demographics and laboratory results at the last pre-HAART visit (age, race-ethnicity, log transformed HIV-RNA, CD4, hemoglobin, serum albumin, and GFR), as well as for relevant clinical conditions (hepatitis C co-infection, diabetes, and blood pressure). Prior AIDS-defining illness (ADI) was ascertained at the first HAART visit, in order to include events that prompted initiation. When data were missing, the value was obtained from the most recent prior visit. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.1.3; SAS).

Results

A total of 2,059 HIV-infected women were enrolled in WIHS during 1994–1995. Among the 1,390 participants who subsequently initiated HAART during the study period, 1,073 (77%) were included in this analysis. Women were excluded if they initiated HAART prior to the second urine visit (n=54), had < 2 eligible urine specimens (n=206), or had > 2 missed visits between the last pre-HAART visit and the first HAART visit (n=57). Excluded women were similar with respect to age and race-ethnicity (data not shown).

Among included participants, 107 (10%) had unconfirmed albuminuria, 42 (4%) had confirmed microalbuminuria, and 33 (3%) had confirmed proteinuria. Albuminuria was associated with black race, as well as with GFR<60ml/min/1.73m2, higher HIV-RNA, higher blood pressure, and lower hemoglobin and serum albumin at the last pre-HAART visit (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included WIHS participants prior to the initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).

| No Albuminuria n=891 (83.0%) |

Unconfirmed Albuminuria n=107 (10.0%) |

Confirmed Microalbuminuria n=42 (3.9%) |

Confirmed Proteinuria n=33 (3.1%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years* | 39.6 (34.5, 44.7) | 42.6 (35.5, 46.5) | 43.8 (35.7,49.1) | 39.2 (34.0, 42.5) |

| Race*** | ||||

| Black (including Hispanic) | 465 (52.2%) | 78 (72.9%) | 34 (81.0%) | 27 (81.8%) |

| White (including Hispanic) | 191 (21.4%) | 17 (15.9%) | 3 (7.1%) | 5 (15.2%) |

| Other | 235 (26.4%) | 12 (11.2%) | 5 (11.9%) | 1 (3.0%) |

| CD4 cell count, cells/mm3 | 280 (149, 430) [n=890] |

231 (122, 406) | 209.5 (125, 325) | 202 (97, 413) |

| Log10 HIV-RNA* | 4.2 (3.3, 4.8) | 4.3 (3.6, 5.0) | 4.3 (3.4, 5.1) | 4.5 (4.0, 5.2) |

| Prior AIDS-defining illness | 449 (50.4%) | 59 (55.1%) | 28 (66.7%) | 18 (54.6%) |

| Hepatitis C co-infection* | 292 (32.8%) | 49 (45.8%) | 17 (40.5%) | 11 (33.3%) |

| Hepatitis B co-infection | 19 (2.1%) | 5 (4.7%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6.1%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 47 (5.3%) | 5 (4.7%) | 4 (9.5%) | 1 (3.0%) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg** | 114 (106, 124) | 120 (110, 130) | 120 (110, 140) | 120 (106, 140) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg*** | 74 (68, 80) | 80 (70, 88) | 80 (73, 90) | 78 (70, 93) |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Current | 454 (51.0%) | 66 (61.7%) | 22 (52.4%) | 19 (57.6%) |

| Former | 215 (24.1%) | 20 (18.7%) | 5 (11.9%) | 8 (24.2%) |

| GFR < 60mL/min/1.73m2 *** | 45 (5.1%) [n=890] |

11 (10.3%) | 13 (31.0%) | 14 (42.4%) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL*** | 12.5 (11.6, 13.4) [n=890] |

12.1 (11.9, 13.2) [n=106] |

11.6 (11.0, 12.2) | 11.4 (10.4, 12.7) |

| Serum albumin, g/dL*** | 4.1 (3.9, 4.4) [n=890] |

4.0 (3.8, 4.2) | 3.9 (3.4, 4.1) | 3.7 (3.3, 4.0) |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Time to HAART initiation, days | 735 (512, 1305) | 721 (518, 1428) | 712 (531, 1088) | 560 (498, 792) |

| Follow-up on HAART, days | 4058 (3207, 4390) | 4045 (3408, 4456) | 4176 (4011, 4333) | 4227 (3280, 4428) |

| Loss to follow-up | 119 (13.4%) | 8 (7.5%) | 1 (2.4%) | 4 (12.1%) |

| Early virologic suppression | 630 (72.5%) [n=869] |

69 (65.1%) [n=106] |

29 (78.4%) [n=37] |

26 (81.3%) [n=32] |

| All-cause death*** | 223 (25.0%) | 39 (36.5%) | 24 (57.1%) | 15 (45.5%) |

| AIDS death** | 98 (11.0%) | 17 (15.9%) | 12 (28.6%) | 3 (9.1%) |

| Non-AIDS death*** | 125 (14.0%) | 22 (20.6%) | 12 (28.6%) | 12 (36.4%) |

Categorical variables are reported as number (%), and continuous variables as median (interquartile range).

p-value: <0.05,

<0.01 and

< 0.001.

Chi-square test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis for continuous variables. Where data are missing, the number of participants with available data is listed. HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; Prior AIDS-defining illness, based on the 1993 Centers for Disease Control surveillance case definition excluding the CD4 criteria, reported at or before the first visit where HAART use was reported; Hepatitis C co-infection, hepatitis C antibody positive and RNA positive or unknown at enrollment; Hepatitis B co-infection, hepatitis B surface antigen positive at enrollment; GFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Time to HAART initiation, time from the second urine visit to HAART initiation; Early virologic suppression, undetectable HIV-RNA at the study visit following the first report of HAART use.

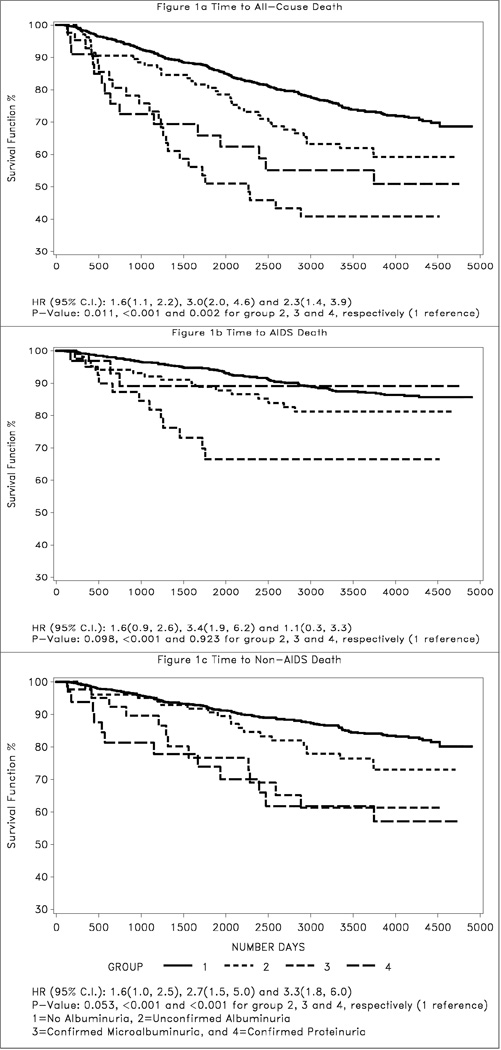

There were 301 deaths during the study period, including 130 AIDS deaths and 171 non-AIDS deaths (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the time to all-cause, AIDS, and non-AIDS death following HAART initiation. Compared to the reference group of women with no albuminuria, women with confirmed microalbuminuria had the highest risk for all-cause mortality (HR 3.0; 95% CI 2.0–4.6), followed by those with confirmed proteinuria (HR 2.3; 95% CI 1.4–3.9). Only confirmed microalbuminuria was significantly associated with AIDS death when considered separately (Figure 1b), while women with either confirmed microalbuminuria or confirmed proteinuria were at increased risk for non-AIDS death (Figure 1c). Women with a single episode of albuminuria were at modestly increased risk for all-cause mortality (HR 1.6; 95% CI 1.1–2.2), but unconfirmed albuminuria was not statistically associated with AIDS or non-AIDS death.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to all-cause (a), AIDS (b), and non-AIDS death (c).

In multivariate analysis (Table 2), confirmed microalbuminuria remained significantly associated with all-cause (HR 1.9; 95% CI 1.2–2.9) and AIDS mortality (HR 2.3; 95% CI 1.3–4.3), but the association with non-AIDS death was no longer significant. Only the association of confirmed proteinuria with non-AIDS death remained significant (HR 2.4; 95% CI 1.2–4.6). In addition to albuminuria, the only other factor that was independently associated with time to both AIDS and non-AIDS death was GFR<60ml/min/1.73m2. Results were similar when the CKD-EPI equation [9] was used to estimate GFR (data not shown). Other factors independently associated with AIDS death included CD4, HIV-RNA, and hemoglobin prior to HAART initiation (Table 2). Factors associated with non-AIDS death included older age, hepatitis C co-infection, current smoking, and lower serum albumin. Although CD4, HIV-RNA, and time to HAART initiation did not predict non-AIDS death, history of ADI remained marginally associated with non-AIDS mortality.

Table 2.

Multivariate proportional hazards models for time to death.

| All-Cause Death Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

AIDS Death Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

Non-AIDS Death Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Albuminuria | |||

| No albuminuria (Reference) | |||

| Unconfirmed albuminuria | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) | 1.3 (0.8, 2.2) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.6) |

| Confirmed microalbuminuria | 1.9 (1.2, 2.9)** | 2.3 (1.3, 4.3)** | 1.7 (0.9, 3.3) |

| Confirmed proteinuria | 1.6 (0.9, 2.8)* | 0.7 (0.2, 2.1) | 2.4 (1.2, 4.6)** |

| GFR < 60mL/min/1.73m2 | 1.9 (1.3, 2.7)*** | 2.1 (1.3, 3.6)** | 1.8 (1.2, 2.9)** |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1)*** | --- | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1)*** |

| CD4 (per 100 cells/mm3) | 0.9 (0.8, 0.9)*** | 0.7 (0.6, 0.8)*** | --- |

| Log10 HIV RNA | 1.2 (1.1, 1.4)*** | 1.4 (1.2, 1.7)*** | --- |

| Prior AIDS-defining illness | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7)* | --- | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) * |

| Hepatitis C co-infection | 1.4 (1.1, 1.8)* | --- | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3)** |

| Smoking history | |||

| Current | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3)** | 1.3 (0.9, 1.9) | 2.8 (1.7, 4.9)*** |

| Former | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.1) | 1.7 (0.9, 3.0) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL (per unit increase) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0)** | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9)*** | --- |

| Serum albumin, g/dL (per unit increase) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9)** | --- | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8)*** |

p-value: 0.05,

<0.01 and

<0.001 by Wald Test.

Hepatitis C co-infection, hepatitis C antibody positive and RNA positive or unknown; GFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate. Race, hepatitis B status, diabetes, blood pressure, and time to HAART initiation were not retained in the final multivariate models, which were based on stepwise selection with a p-value < 0.05 for retention.

Discussion

We have previously demonstrated an increased risk of all-cause and AIDS-related mortality among HIV-infected women with microalbuminuria prior to the introduction of HAART. [5] In the current analysis of 1,073 HIV-infected women who subsequently initiated HAART, pre-existing microalbuminuria was associated with a similar 2-fold increase in the risk of all-cause and AIDS death. These observations suggest that screening for albuminuria may identify HIV-infected individuals at increased risk for mortality even after HAART initiation.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), as indicated by overt proteinuria or decreased GFR, has been associated with increased mortality in the general population and in HIV-infected women. [10][11] [12] [13] In an earlier analysis of WIHS censored in 2002, proteinuria detected by routine urinalysis was associated with a more than 2-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality among women who initiated HAART, although deaths were not classified by relationship to AIDS. [11] More recently, studies in predominantly male populations have demonstrated associations between overt proteinuria and cardiovascular events in HIV-infected individuals. [14] [15] While detailed data on cause of death were not available for the current analysis, cardiovascular disease was a common cause of non-AIDS mortality in an earlier analysis of WIHS. [16] Future studies should consider whether HIV-infected individuals with overt proteinuria would benefit from more intensive management of cardiovascular risk factors and other comorbidities that may contribute to non-AIDS mortality.

Microalbuminuria has also been associated with mortality and cardiovascular disease in HIV-negative patient populations. [4] Although microalbuminuria may indicate early CKD, it has also been hypothesized to reflect systemic inflammation [3] and generalized endothelial dysfunction. [4] In a prior analysis of 162 WIHS participants with serial albuminuria measurements, albuminuria stabilized in women who initiated HAART, but continued to increase in untreated controls. [17] Microalbuminuria was hypothesized to reflect inflammation and endothelial dysfunction resulting from active viral replication. The results of the current analysis suggest that pre-existing microalbuminuria may continue to predict AIDS-related outcomes even after the initiation of HAART.

Future studies are needed to determine whether microalbuminuria predicts mortality in HIV-infected men or from specific causes. Other important limitations are the possible underestimation of albuminuria in women taking angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and the misclassification of women who developed new albuminuria in the interval between the confirmatory urine test and HAART initiation. Misclassification may also have occurred due to the limited sensitivity of dipstick assays to detect lower levels of proteinuria [18] and microalbuminuria, or due to decreased sensitivity of microalbuminuria testing in banked urine.[19] These types of misclassification, however, would be expected to bias our results towards the null. Finally, we had limited power to exclude an association between overt proteinuria and AIDS mortality or to evaluate the effect of individual ART regimens.

The current study suggests that albuminuria testing before initiation of HAART may identify individuals at increased risk for mortality despite HAART. Screening for CKD, including assessment for overt proteinuria, is currently standard of care in HIV-infected individuals.[20] Future studies should investigate whether additional microalbuminuria testing is a cost-effective approach to identify high-risk patients, who may benefit from more aggressive management of comorbidities and behavioral factors known to contribute to mortality.

Acknowledgements

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group with centers (Principal Investigators) at New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff); Washington DC Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); The Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); Data Coordinating Center (Stephen Gange). The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (UO1-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590) and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (UO1-HD-32632). The study is co- funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Funding is also provided by the National Center for Research Resources (UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131). CMW is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (K23-DK-077568). PCT is supported by NIAID (K23-AI-66943). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- 1.Kimmel PL, Umana WO, Bosch JP. Abnormal urinary protein excretion in HIV-infected patients. Clin Nephrol. 1993;39:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szczech LA, Grunfeld C, Scherzer R, et al. Microalbuminuria in HIV infection. AIDS. 2007;21:1003–1009. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280d3587f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baekken M, Os I, Sandvik L, Oektedalen O. Microalbuminuria associated with indicators of inflammatory activity in an HIV-positive population. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3130–3137. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerstein HC, Mann JF, Yi Q, et al. Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. JAMA. 2001;286:421–426. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyatt CM, Hoover DR, Shi Q, et al. Microalbuminuria Is Associated With All-Cause and AIDS Mortality in Women With HIV Infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181cc1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, et al. The Women's Interagency HIV Study. WIHS Collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology. 1998;9:117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen MH, French AL, Benning L, et al. Causes of death among women with human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. Am. J. Med. 2002;113:91–98. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01169-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60674-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szczech LA, Hoover DR, Feldman JG, et al. Association between renal disease and outcomes among HIV-infected women receiving or not receiving antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1199–1206. doi: 10.1086/424013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardner LI, Holmberg SD, Williamson JM, et al. Development of proteinuria or elevated serum creatinine and mortality in HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:203–209. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200302010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estrella MM, Parekh RS, Abraham A, et al. The impact of kidney function at HAART initiation on mortality in HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e674f4. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George E, Lucas GM, Nadkarni GN, Fine DM, Moore R, Atta MG. Kidney function and the risk of cardiovascular events in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS. 2010;24:387–394. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283359253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi AI, Li Y, Deeks SG, Grunfeld C, Volberding PA, Shlipak MG. Association between kidney function and albuminuria with cardiovascular events in HIV-infected persons. Circulation. 2010;121:651–658. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.898585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.French AL, Gawel SH, Hershow R, et al. Trends in mortality and causes of death among women with HIV in the United States: a 10-year study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:399–406. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181acb4e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szczech LA, Golub ET, Springer G, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy reduces urinary albumin excretion in women with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48(3):360–361. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31817beba1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siedner MJ, Atta MG, Lucas GM, Perazella MA, Fine DM. Poor Validity of Urine Dipstick as a Screening Tool for Proteinuria in HIV-Positive Patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:261–263. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815ac4ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brinkman JW, de Zeeuw D, Lambers Heerspink HJ, et al. Apparent loss of urinary albumin during long-term frozen storage: HPLC vs immunonephelometry. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1520–1526. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.088823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta SK, Eustace JA, Winston JA, et al. Guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected patients: recommendations of the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1559–1585. doi: 10.1086/430257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]