Abstract

Communities are being encouraged to develop locally-based interventions to address environmental risk factors for obesity. Online public directories represent an affordable and easily accessible mechanism for mapping community food environments, but may have limited utility in rural areas. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of public directories versus rigorous onsite field verification to characterize the community food environment in 32 geographically-dispersed towns from two rural states, covering 1237.6 square miles. Eight types of food outlets were assessed in 2007, including food markets and eating establishments, first using two publically available online directories followed by onsite field verification by trained coders. Chi-square and univariate binomial regression were used to determine whether the proportion of outlets accurately listed varied by food outlet type or town population. Among 1340 identified outlets, only 36.9% were accurately listed through public directories; 29.6% were not listed but were located during field observation. Accuracy varied by outlet type, being most accurate for big box stores and least accurate for farm/produce stands. Overall, public directories accurately identified less than half of the food outlets. Accuracy was significantly lower for rural and small towns compared to mid-size and urban towns. In this geographic sample, public directories seriously misrepresented the actual distribution of food outlets, particularly for rural and small towns. To inform local obesity-prevention efforts, communities should strongly consider utilizing field verification to characterize the food environment in low population areas.

Keywords: Food outlets, rural, fast food, convenience store, field validation, obesity

Background

Rural residence is an important correlate of obesity (1,2). Characteristics of rural environments, including limited access to healthy foods, may influence obesity-related behaviors (3). In response to increasing calls for environmentally-based modifications to address obesity (4-6), communities are developing local interventions targeting geographic risk factors (7-9). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends appropriate measurement of community food environments to inform these obesity prevention strategies (4). Although onsite field validation is recognized as the gold standard for identifying community food sources, this method is both costly and time-intensive, particularly for rural areas characterized by large expanses of undeveloped land (10,11). Use of secondary data sources, such as those available through commercial databases and public directories, offer local communities an easily accessible and typically no-cost mechanism for mapping their food environment. More research is needed, however, on the validity of secondary data sources for describing food environments in rural areas (12-14).

Several researchers have compared the accuracy of secondary data sources versus field validation in urban communities outside of the U.S. These studies report accuracy between 65-85% for commercial databases and local government listings, and between 50-65% for Internet-based listings (14-16). All three types of secondary data sources are not without limitations. Specifically, commercial databases may exclude information on low-revenue, locally-owned food establishments; listings within governmental databases may have insufficient information to classify food outlet types in detailed categories; and Internet listings may be updated infrequently (13,14).

Few studies have compared the validity of secondary data sources versus field validation in rural areas of the U.S. Sharkey found that public lists omitted between 20-36% of field validated food markets in six impoverished, remote counties in Central Texas (17). Additionally, only one study, conducted in an urban city in the United Kingdom, examined the accuracy of secondary sources by differing food outlet types, such as food markets and restaurants (14). Lake et al. demonstrated that restaurants and pubs were most likely to be listed on public data sources but not found in the field. Others have recognized specific challenges in using commercial databases to characterize unique food environments, such as those associated with ethnic minority communities (18). Similarly, commercial data sources may have limited utility in rural compared to urban areas because of lower precision geocoding (19,20) and a greater presence of smaller, locally-owned establishments for procuring foods (e.g., seasonal farm stands, general stores). The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the efficacy of using secondary data sources versus rigorous field validation to characterize the food environment in two predominantly rural states. Specific aims investigated whether accuracy varied by food outlet type or by degree of rurality. Information obtained from two public directory Internet sites was selected for comparison with field validation because it was expected that these data would be most easily and quickly accessible by local communities.

Methods

Data for the current study were collected as part of a larger study of individual, family, and environmental influences on adolescent obesity in primarily rural and small town geographic areas of Northern New England. The study, titled Environmental and Family Influences on Adolescent Overweight, was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College.

Data Collection

In 2007 two public directory Internet sites were used to create an inventory of town-wide food outlets for 32 geographically dispersed towns throughout New Hampshire (NH) and Vermont (VT). Food outlet data were first collected via the “Places of Interest” function on Google Earth, which provides business and geographic location data gathered from a variety of commercial sources (21). Secondly, the inventory was augmented using Yahoo! Yellow Pages. Yahoo! Yellow Pages (which was functioning in 2007, but closed as of March 2010 and replaced by Yahoo! Local) collects business listings through its data provider, InfoUSA, one of the largest commercial business databases worldwide (22,23). It was expected that these two sites would maximize the advantages of both commercial and Internet listings.

Towns were selected based on town-of-residence for an ongoing study (24). ArcGIS 9.1 (ESRI, 2004, Redlands, CA) was employed to create an aerial photo map of each town that identified town boundaries, street networks, and inventoried food outlet locations derived from the public directories. Field verification was conducted within one month of public directory data collection by two-person coding teams who systematically drove all town street networks, confirmed the presence and location of inventoried food outlets, and identified onsite outlets not included on the inventory. The accuracy of public directories versus field observations was evaluated as follows: outlet identified on Internet and found at expected location (accurately listed); outlet identified on Internet and found at a different location (mislocated); outlet identified on Internet but not found through field observation (not found); outlet not identified on Internet but found through field observation (not listed). Outlets were considered mislocated if coders could not visually locate the outlet while positioned at the Internet-identified location. Categorization into the accuracy groups was based on the two-person coding decisions during onsite town visits and utilized geocoded food outlet location data and detailed town maps.

Field coders used a structured Community Food Observation Form (CFOF) and a detailed manual, developed for the current study, to categorize and describe food outlets. The CFOF was developed by a team of experienced researchers and geographic experts after a thorough review of the literature and extensive observations in towns of similar size and rurality to the study towns. Prior to data collection, we pretested the public data download process and the CFOF in four non-study towns, which allowed us to establish face validity and comprehensiveness of the food outlet categories. During pretesting, we evaluated inter-rater reliability of the coders' field observations, including identification of all food outlets, and categorization of food outlet type. We found 100% agreement between the two coding teams for each of these measures.

Coders classified outlets as either food markets, consisting of six specific outlet categories (general store; convenience store; supermarket/grocery store; specialty food store; “big box” store; seasonal and year-round fixed location farm/produce stand) or eating establishments, consisting of two outlet categories (fast food restaurants, defined as any food outlet where the patron orders food at a counter or window; and full-service restaurants). General stores are defined as local retailers with a broad selection of merchandise, including grocery items, hardware, and gardening supplies. Big box stores included warehouse membership clubs (e.g. B.J.'s, Sam's Club) and large retail supercenters, provided they contained packaged food/grocery sections. Specialty food stores included food outlets that exclusively sold a specific type of food, such as meat or fish markets. In-store observations were conducted to verify outlet classification. The resulting eight categories represent a modified version of the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) (25). Food markets housing a fast food business (n=43) were counted as two distinct outlets if, based on in-store observations, the fast food section had a separate name or logo, entryway, cash register, or employee. Town population was used as an indicator of rurality and categorized as: <2,499 (rural); 2,500-4,999 (small town); 5,000-9,999 (mid-sized town); >=10,000 (urban) (26).

Statistical Analysis

For analyses, outlet classification was dichotomized as accurately listed versus not (mislocated + not found + not listed). Chi-square analysis was used to determine if the proportion of outlets accurately listed varied by food outlet type. Univariate binomial regression, which accounts for the number of outlets/town, was employed to determine if the proportion of outlets accurately listed varied by town population. Data were analyzed in 2010 using Stata 9.1 (27).

Results and Discussion

The sampling area covered 1237.6 square miles, encompassing 7% of the total combined land area in NH and VT. Towns were well-distributed by population size: rural, n=11; small town, n=7; mid-sized town, n=8; and urban, n=6. Nine hundred forty-three food outlets were identified through public directory listings, and 960 through field observations. After accounting for overlap, this provided a sample of 1340 unique food outlets. Twenty-seven percent were food markets and 73% were eating establishments. The number of food outlets per town ranged from 1 to 275. The majority of outlets were located in either urban (62.5%, n=837) or mid-size towns (25.7%, n=345); 5.5% (n=74) were located in small towns, and 6.3% (n=84) were in rural towns. Overall, only 36.9% of identified outlets (n=495) were accurately listed through public directories, and 5.1% (n=68) were mislocated. More than one-quarter (28.4%, n=380) of outlets were identified on public directories but not found during field observation. Thirty percent (29.6%, n=397) were not listed through public directories but were located in the field.

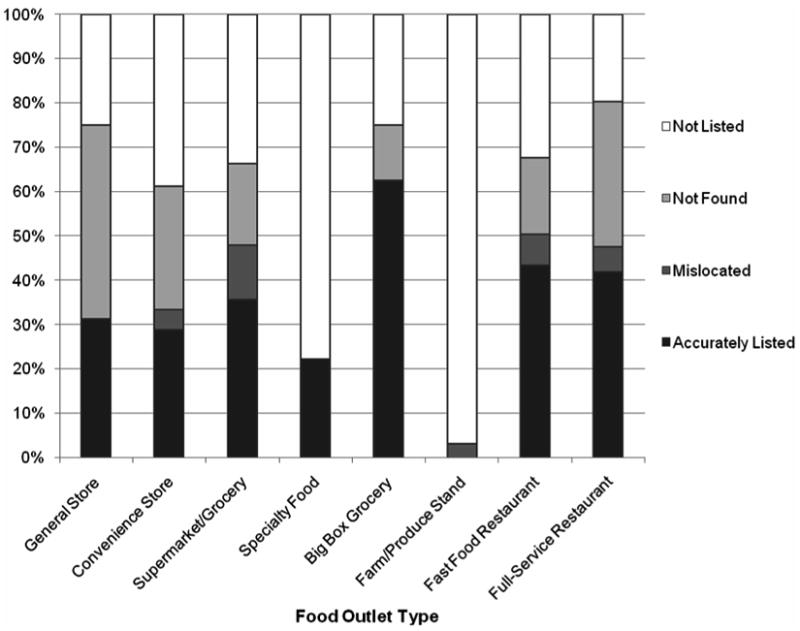

With the exception of big box stores, less than half of all outlet types were accurately listed on the public directories. Public directory accuracy differed significantly by outlet type (Figure 1, P<0.001). Accuracy was highest for big box stores (62.5%), and eating establishments (43.5% fast food restaurants; 42% full-service restaurants). None of the farm/produce stands and only 35.7% of supermarket/grocery stores were accurately identified through public directories, thus omitting important community sources of fresh produce.

FIGURE 1. Accuracy of Public Directory Data to Identify Community Food Outlets by Outlet Type.

Note. Public directory (i.e., Google Earth and Yahoo! Yellow Pages) accuracy was evaluated as follows: “accurately listed” (outlet identified on Internet and found at expected location; “mislocated” (outlet identified on Internet and found at a different location); “not found” (outlet identified on Internet but not found through field observation); “not listed” (outlet not identified on Internet but found through field observation).

Sample sizes for food outlet types: general store (n=16), convenience store (n=245), supermarket/grocery (n=65), specialty food (n=9), big box grocery (n=8), farm/produce stand (n=17), fast food restaurant (n=451), full-service restaurant (n=527). Two outlets identified on the Internet but not found through field observation could not be categorized into an outlet type.

Chi-square analyses demonstrates that the proportion of outlets accurately listed versus not (e.g., mislocated + not found + not listed) differs significantly by food outlet type (P<0.001).

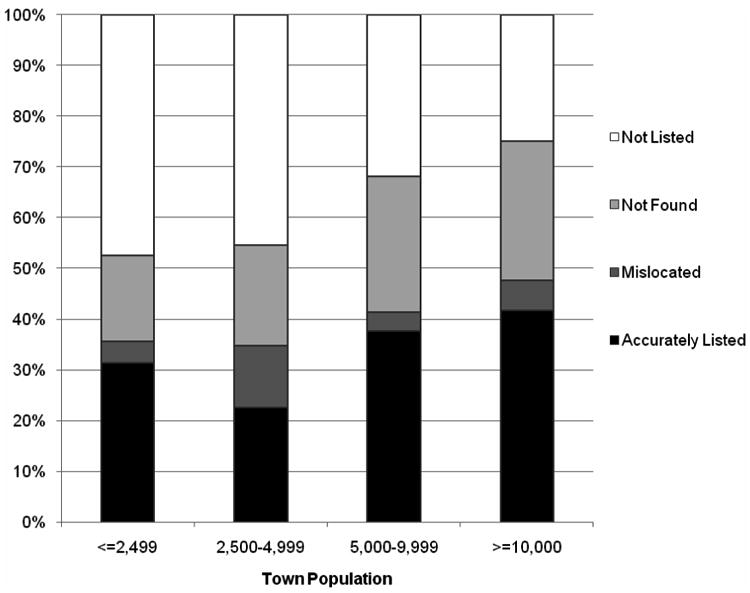

Less than 50% of food outlets in all four town population groups were accurately identified through public directory data. Public data were significantly less accurate for low population towns (Figure 2, P<0.001). Approximately three-quarters of the outlets in rural and small towns (68.6% and 77.3%, respectively) were inaccurately identified through public directories, compared to about 60% in mid-sized (62.4%) and urban (58.2%) towns.

FIGURE 2. Accuracy of Public Directory Data to Identify Community Food Outlets by Town Population.

Note. Public directory (i.e., Google Earth and Yahoo! Yellow Pages) accuracy was evaluated as follows: “accurately listed” (outlet identified on Internet and found at expected location; “mislocated” (outlet identified on Internet and found at a different location); “not found” (outlet identified on Internet but not found through field observation); “not listed” (outlet not identified on Internet but found through field observation).

Sample sizes for town population categories: <=2,499 (n=11); 2,500-4,999 (n=7); 5,000-9,999 (n=8); >=10,000 (n=6).

Univariate binomial regression demonstrates that the proportion of outlets accurately listed versus not (e.g., mislocated + not found + not listed) differs significantly by town population group (P<0.001).

Limitations

The accuracy of public directories versus field observations was only coded once during onsite town visits and so we did not measure whether these categories were miscoded. To minimize the chance of categorization errors, we extensively trained the coders during pre-testing, provided detailed town driving maps, located the public directory food outlets prior to the town visits, and used two-person teams for all townwide assessments. Google Earth and Yahoo! Yellow Pages utilized data from multiple commercial sources (e.g., InfoUSA) and thus it was expected that these data would be similar to that obtained through commercial databases. For current purposes, Google Earth had the added advantage of providing an efficient mechanism for downloading geographic coordinates data to create the townwide maps used during onsite field validation. It is possible that our results would have been different if we had utilized data from a primary commercial database. The secondary data gathered may also have differed if NH and VT government databases, such as those available within state Departments of Agriculture, had been utilized. However, this information is not geographically referenced and involves aggregating data from multiple reports, both of which would make data collection and verification more burdensome for local communities. Finally, this study was regionally based and so the findings may not be generalizable to other geographic areas.

Conclusions

This study represents one of the largest samples of food outlets to date validated through field verification methods, identifying nearly 1,000 outlets in the primarily low population sampling area. The sample included four distinct population patterns within a relatively small geographic area, and assessed eight types of food outlets, providing a comprehensive description of the regional food environment. The efficacy of using public directories to identify community food outlets in predominantly rural states was low, with nearly two-thirds of all outlets in the sampling area inaccurately identified through public data sources. Accuracy varied significantly by food outlet type, and by town population size.

Among this geographic sample of towns located in two predominantly rural states, public directories seriously misrepresent the actual distribution of food outlets, particularly for food markets and rural and small towns. Additional research conducted in differing geographic regions of the U.S. is needed to establish whether the accuracy of public data sources similarly varies by food outlet type and within other rural locales. To inform local obesity-prevention efforts, communities should strongly consider utilizing field verification to characterize the food environment in low population areas. However, in the absence of sufficient resources for field verification, community residents might consider using multiple sources of data to compensate for inaccurate or missing information from single sources. For example, to address inaccurate public directory information on farm and produce stands, the United States Department of Agriculture (UDSA) provides a national Farmers' Market Directory which can be searched by state, city, county or zip code (28). Many town municipality websites provide links to area year-round and seasonal farmers' markets as well. Community residents could encourage their local or state governments to augment this information with accurate data on other townwide food outlets providing fresh produce (e.g., supermarkets, grocery stores, and year-round produce stands). Ideally, State Department of Agriculture websites should provide accurate, geolocated data on healthy food sources for communities. Finally, the new Food Environment Atlas, available from the USDA (29), provides a wealth of descriptive information on the food environment at the county level. This data source may be useful for researchers wishing to characterize counties and states on a number of healthful food environment indicators. However, because the food environment is constantly changing, the accuracy of these data will also need to be evaluated.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jackson JE, Doescher MP, Jerant AF, Hart LG. A national study of obesity prevalence and trends by type of rural county. J Rural Health. 2005;21:140–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lutfiyya MN, Lipsky MS, Wisdon-Behounek J, Inpanbutr-Martinkus M. Is rural residency a risk factor for overweight and obesity for U.S. children? Obesity. 2007;15:2348–2356. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O'Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: Policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan LK, Sobush K, Keener D, Goodman K, Lowry A, Kakietek J, Zaro S. Recommended Community Strategies and Measurements to Prevent Obesity in the United States. MMWR Recommendations & Reports. 2009;58(RR07):1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O'Brian R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: Policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity Report to the President. Solving the Problem of Childhood Obesity within a Generation. [Accessed May 12, 2010];2010 May; doi: 10.1089/bfm.2010.9980. http://www.letsmove.gov. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Public Health Law and Policy. Healthy Corner Stores: The State of the Movement. [Accessed May 12, 2010]; http://healthycornerstores.org/resources/reports.

- 8.Strategic Alliance for Healthy Food and Activity Environments. ENACT Neighborhood Environment: Fast Food. [Accessed May 12, 2010]; http://www.eatbettermovemore.org/sa/enact/neighborhood/ENACTNeighborhoodEnvironmenFastFood.php.

- 9.Healthy Eating Active Living Convergence Partnership. Healthy people, healthy places. [Accessed May 12, 2010]; www.convergencepartnership.org.

- 10.Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: Disparities in access to healthy foods in the U S. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharkey JR. Measuring potential access to food stores and food-service places in rural areas in the U S. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4S):S151–S155. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinnon RA, Reedy J, Morrissette MA, Lytle LA, Yaroch AL. Measures of the food environment: A compilation of the literature, 1990-2007. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4S):S124–S133. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang MC, Gonzalez AA, Ritchie LD, Winkleby MA. The neighborhood food environment: Sources of historical data on retail food stores. Int J Beh Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:15. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lake AA, Burgoine T, Greenhalgh F, Stamp E, Tyrrell R. The foodscape: Classification and field validation of secondary data sources. Health Place. 2010;16:666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paquet C, Daniel M, Kestens Y, Leger K, Gauvin L. Field validation of listings of food stores and commercial physical activity establishments from secondary data. Int J Beh Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:58. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cummins S, Macintyre S. Are secondary data sources on the neighbourhood food environment accurate? Case-study in Glasgow, UK. Prev Med. 2009;49:527–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharkey JR, Horel S. Neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation and minority composition are associated with better potential spatial access to the ground-truthed food environment in a large rural area. J Nutr. 2008;138:620–627. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.3.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Odoms-Young AM, Zenk S, Mason M. Measuring food availability and access in African-American communities: Implications for intervention and policy. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4S):S145–S150. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creel JS, Sharkey JR, McIntosh A, Anding J, Huber JC., Jr Availability of healthier options in traditional and nontraditional rural fast-food outlets. Public Health. 2008;8:395. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kravets N, Hadden WC. The accuracy of address coding and the effects of coding errors. Health Place. 2007;13:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Google Earth. Using Layers: Places of Interest (POIs) [Accessed July 15, 2010];2010 http://earth.google.com/support/bin/static.py?page=guide.cs&guide=22370&topic=22652&answer=180709. Published.

- 22.Yahoo!® Help. How can I add my business listing to Yahoo! Yellow Pages? [Accessed July 15, 2010];2010 http://help.yahoo.com/l/us/yahoo/yp/about/yp-09.html. Published.

- 23.Infogroup / InfoUSA.com. [Accessed July 15, 2010];2010 About us. http://www.infousa.com/Static/AboutUs/83552/S71567047313615. Published.

- 24.Owens P, Titus-Ernstoff L, Gibson L, Beach M, Beauregard S, Dalton M. Smart density: A more accurate method of measuring rural residential density for health-related research. Int J Health Geogr. 2010;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Census Bureau. North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) [Accessed May 12, 2010]; Available at: http://www.census.gov/eos/www/naics/index.html.

- 26.U.S. Census Bureau. Population Estimates: Cities and Towns-Minor Civil Divisions, 2000-2007. [Accessed May 12, 2010]; Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest/cities/SUB-EST2007-5.html.

- 27.STATA Statistical Software (for Windows). [computer program]. Version 9.1. College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Department of Agriculture. Farmers' Markets and Local Food Marketing. [Accessed September 1, 2010]; Available at: http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/FarmersMarkets.

- 29.U.S. Department of Agriculture. Your Food Environment Atlas. [Accessed July 26, 2010]; Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/FoodAtlas.