Abstract

Paget disease of the bone is a chronic disease characterized by accelerated bone turnover with abnormal repair leading to expansion, pain and deformities. The disease is common in the West, but little if any information is available on its existence in the Arab world, including Saudi Arabia. We present four cases of Saudi patients with Paget disease with variable presentations. The first case, a 63-year-old woman with a history of papillary thyroid cancer, presented with bone, shoulder and chest wall pain and foci of uptake in the ribs and skull that were thought to be metastases, indicating the possibility of diagnostic difficulty in a patient with history of malignancy. Bone biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of Paget disease. The second case was a 47-year-old asymptomatic woman with an elevated alkaline phosphatase of 427 U/L, a common presentation but at an unusual age. Plain x-rays and bone scan confirmed the diagnosis. The third case was a 43-year-old man who presented with hearing impairment and right knee osteoarthritis, unusual presentations at a young age leading to a delay in diagnosis. The fourth case was a 45-year-old man who presented with sacroiliac pain and normal biochemical values, including a normal alkaline phosphatase. Bone biopsy unexpectedly revealed features of Paget disease, which evolved over time into a classical form. A common feature in all except the first case was the relatively young age. Paget disease does exist in Saudi Arabia, and it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of similar cases.

Paget disease of the bone is a chronic skeletal disorder characterized by areas of osteoclast-mediated increased bone resorption followed by a disorderly osteoblast-mediated bone repair.1 This process of abnormal bone remodeling leads to areas of bone expansion and distortion accompanied by pain, increased risk of fracture, deformities, compression of adjacent structures and rarely, neoplastic transformation.2 The disease affects mostly middle-aged-to-elderly individuals, with a slight male predominance.1,2 Paget disease affects mostly whites and is most prevalent in western Europe and North America.3,4 It is also common in Australia and New Zealand, but its prevalence in other races is much lower.4 In Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of the disease is believed to be very low, but there are no epidemiological studies to document the exact prevalence of the disease. An extensive Medline search yielded only a single case report from Saudi Arabia published in 1985 and a few cases in Arab Bedouins from occupied Palestine.6,7 While it is likely that the disease has low prevalence in this part of the world, it is also possible that it is overlooked and that many cases of Paget disease are missed. This is likely since the disease is frequently asymptomatic2,8 and its consideration in the differential diagnosis of bone pain or asymptomatic elevation of alkaline phosphatase is infrequent. In this report, we present a case series of four Saudi patients with Paget disease who had different presentations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest case series from an Arab country. Our aim is to remind physicians in this region of this “rare” disease and to highlight its variable presentations and the potential misdiagnosis, which may result in unnecessary tests and potentially serious interventions.

CASE 1

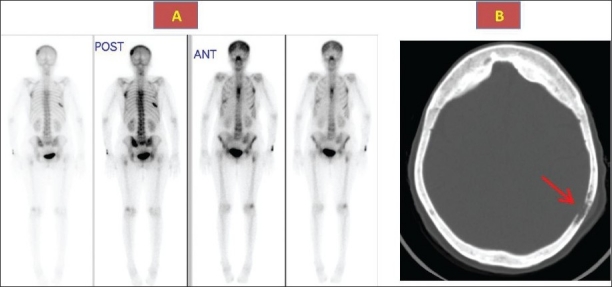

A 63-year-old woman was diagnosed with papillary thyroid carcinoma with tracheal invasion in 1998. At that time, she underwent total thyroidectomy with tracheal resection and primary anastomosis followed by local external radiation therapy at a total dose of 6000 cGy. Since she could not be isolated in a single room, she was not given radioactive iodine therapy. In April 2000, she presented at a local hospital with severe localized bone pain, mainly in the shoulders and chest wall, and she was admitted. Investigations included a bone scan that showed multiple areas of increased uptake in the skull and ribs. Based on that, she was thought to have bone metastases from the previously diagnosed papillary thyroid cancer. She was referred to our hospital for further management. She gave no history of bone deformities, fractures, hearing impairment or chronic headache. Physical examination was remarkable for bony tenderness over the lower ribs bilaterally. Laboratory investigations provided normal results except for a mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase, of 165 U/L (normal range, 50-120 U/L). Serum calcium was 2.31 mmol/L (normal range, 2.1-2.60 mmol/L), albumin was 31 g/L (normal range, 28-46 g/L) and phosphate was 1.11 mmol/L (normal range, 0.8-1.45 mmol/L). Parathyroid hormone was normal at 52 ng/dL (normal range, 15-65 ng/dL), and 25-OH vitamin D was 45 nmol/L (normal range, 22-116 nmol/L). Serum thyroglobulin was less than 0.1 ng/dL; anti-thyroglobulin antibodies, 13 U/L (normal, <115 U/L); TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone), 2.92 mU/L (normal range, 0.4-4.27 mU/L); and FT4 (free thyroxine), 14.6 pmol/L (normal range, 12-22 pmol/L). A radioiodine whole-body scan 1 year earlier was negative with an undetectable thyroglobulin while off thyroid hormone therapy, with a TSH of 30 U/L and FT4 of 0.4 pmol/L, indicating complete remission of papillary thyroid cancer. Plain x-ray of the thoracic spine revealed compression fractures of thoracic vertebrae. A bone scan showed areas of increased uptake in parietal bone, ribs and thoracic vertebra, which were reported to be highly suggestive of bony metastases (Figure 1). CT of the skull showed multiple lytic and sclerotic lesions (Figure 1b). Since the clinical picture was atypical for bone metastases with an undetectable thyroglobulin level, a negative whole-body scan and absence of lung metastases, it was decided to proceed with a bone biopsy from one of the rib lesions. This was done under CT guidance and showed a distorted bone structure with multinucleated osteoclasts in a picture consistent with the diagnosis of Paget disease. She was started on alendronate 20 mg orally daily, with significant symptomatic improvement and normalization of alkaline phosphatase over the next 3 months. She was lost for follow-up without explanation.

Figure 1.

Bone scan (1a) showing foci of increased activity in the ribs, skull, spine and CT skull (1b) showing thickened sclerotic and lytic lesions (arrow) consistent with Paget disease.

CASE 2

A 49-year-old woman was referred to an endocrine clinic for management of diabetes mellitus that was diagnosed 12 years earlier and hypothyroidism diagnosed 4 years earlier. She was completely asymptomatic without bone pain or swelling, loss of height, fractures or hearing impairment. She had no hyperglycemic or hypoglycemic symptoms, hyperthyroid or hypothyroid symptoms or goiter. She was taking L-thyoxine 100 mcg daily, metformin 500 mg three times daily and gliclazide long-acting 90 mg daily. The physical examination was unremarkable, without evidence of bone deformity, kyphoscoliosis or enlarged skull. Laboratory evaluation revealed a normal complete blood count, creatinine and electrolytes. Fasting blood sugar was 6.7 mmol/L; and glycated hemoglobin, 7.4%. TSH was 1.4 U/L (normal range, 0.4-4.27 U/L). The only laboratory abnormality was an unexpectedly high serum alkaline phosphatase of 427 U/L (50-120). When repeated, it showed a similar elevation of 432 U/L. The workup to rule out hepatobiliary disease included ALT, AST, gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), bilirubin, a hepatitis C and B screen and ultrasound of the liver and biliary system; all had normal results. Consideration was given to the possibility of metabolic bone disease, and investigations included serum calcium of 2.38 mmol/L; phosphate, 1.29 mmol/L (normal range, 0.8-1.40 mmol/L); 25-OH vitamin D, 32 nmol/L (normal range, 25-150 nmol/L); and parathyroid hormone, 22.2 ng/dL (normal range, 15-65 ng/dL). The possibility of metastases of unknown origin was another consideration. A bone scan revealed an increased uptake with an image and distribution consistent with Paget disease of the bone (Figure 2a). Plain x-rays and CT of the skull showed typical bony changes of Paget disease (Figure 2b). The patient was treated with alendronate 40 mg daily for 6 months, leading to normalization of alkaline phosphatase. On follow up for about 4 years, she had a repeatedly normal alkaline phosphatase and other biochemical and clinical parameters and faint activity of her disease on bone scans.

Figure 2.

Bone scan (2a) showing extensive activity in the skull, spine and iliac crests. CT skull (2b) shows significant thickening and distortion with lytic areas.

CASE 3

A 43-year-old man noticed a significant decrease in hearing over 1 year with no ear pain or discharge. He also complained of intermittent pain and occasional swelling in the right knee. An ear examination was unremarkable, with intact drums and an absence of discharge. A knee examination revealed right knee effusion with mild tenderness. Laboratory evaluation was normal except for elevated alkaline phosphate, which was 319 U/L (normal range, 40-115 U/L), with normal ALT, AST, and bilirubin. Serum calcium was 2.51 mmol/L; phosphate, 1.10 mmol/L; 25-OH vitamin D, 81 nmol/L (normal range, 25-150 nmol/L); and parathyroid hormone, 20 ng/L (normal range, 15-65 ng/L). An audiogram was positive for sensorineural deafness. none CT of the skull showed a sclerotic lesion in the temporal bone. X-rays of the knees showed osteoarthritic changes. Paget disease was suspected, and the bone scan showed typical changes of Paget disease (Figure 3). He was started on pamidronate 60 mg intravenously given twice over a 6-month period. He had significant improvement in alkaline phosphatase. A follow-up scan 1 year after treatment showed improvement.

Figure 3.

Bone scan showing increased activity in the dorsal spine, knees, shoulder and ankles.

CASE 4

A 45-year-old man was referred to our institution in 1989 with severe pain in the left sacroiliac region for the previous 3 months. He reported no other joint pains, skeletal deformities, fractures or hearing impairment. Physical findings were positive for tenderness over the sacroiliac joints but there were no other abnormalities. Systemic examination was unremarkable. Laboratory investigations showed normal alkaline phosphatase (106 U/L) with normal calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone and 25-OH vitamin D. Tumor markers were all negative, including prostate-specific antigen. Plain x-ray showed sclerotic lesions in the left ileum, pubis, ischium and the fifth lumbar vertebra. A bone scan showed an increased uptake in the same areas, suggestive of bony metastases. Bone biopsy showed pagetoid bone changes (Figure 4). At the time of presentation, the patient was treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In 1992, he started having a gradual increase in alkaline phosphatase with worsening of sacroiliac pains. He was started on etidronate 400 mg twice daily, but continued to have active disease. In 1993, he was treated with calcitonin 100 mg subcutaneously daily. He continued to have elevated alkaline phosphatase with pain in the lower back and right maxillary area. In 1998, alendronate was approved by the FDA for management of Paget disease, so he was started on alendronate 40 mg orally daily. His symptoms improved significantly, and alkaline phosphatase normalized over the next 2 years with remarkable improvement in the bone scans. Alendronate was stopped, but he needed another 6-month course in 2008, which again led to control of his symptoms and normalization of alkaline phosphatase with significant improvement in the uptake on bone scan.

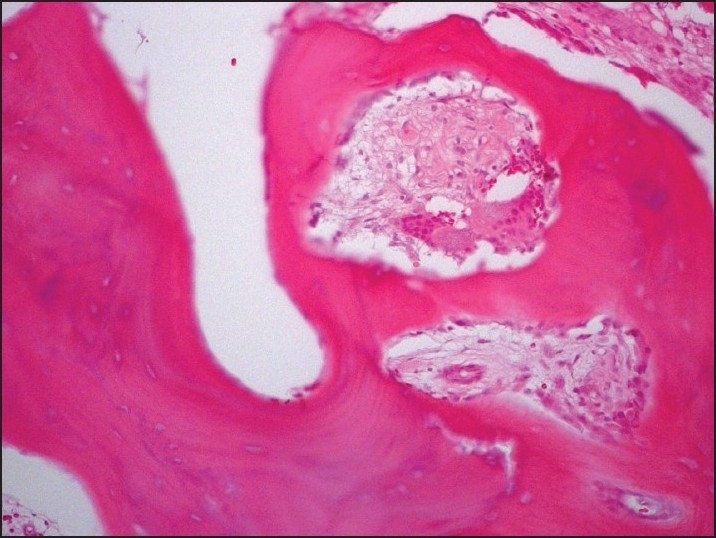

Figure 4.

Bone biopsy showing extensive deposition of osteoid with distortion of the bone structure and multinucleated osteoclasts.

DISCUSSION

Paget disease of the bone, also known as osteitis deformans, was first described in a small group of patients in 1877 by Sir James Paget.9 It is a focal skeletal disorder characterized by an accelerated bone turnover.2,10 The incidence of Paget disease is difficult to estimate because most patients are asymptomatic.1–3,10 The incidence appears to increase with age, and there seems to be a slight male preponderance.11 The disease is most common in nations with a large Anglo-Saxon population but is considered rare in other parts of the world.3,4 In Saudi Arabia, little information has been published about this disease. In this paper, we describe a series of four cases that illustrate some interesting aspects of this disease and its variable presentations.

In the first case, the diagnosis was initially thought to be metastatic papillary thyroid cancer as the patient was known to have this disease before and the skeleton is a well-known site for thyroid cancer metastases. Although there were some unusual features for metastases of papillary thyroid cancer, the initial aggressive features of the tumor could have justified acceptance of the presence of such metastases as the reason for the pain and the bone lesions on bone scan. Although biopsy is rarely needed in the diagnosis of Paget disease, when uncertainty remains, a bone biopsy can be diagnostic.1

The second case was a completely asymptomatic patient with diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism. She was unexpectedly found to have a significantly elevated alkaline phosphatase. Due to the rarity of this disease in this part of the world and the relatively young age of the patient, Paget disease was not considered initially, and more common diagnoses such as hepatobiliary disease and osteomalacia were initial considerations. It is only when the bone scan was done in a search for possible metastases from an unknown primary tumor that the diagnosis of Paget disease was clear.

The third patient presented with hearing impairment and intermittent knee pain. The two complaints were not initially correlated, again because of the rarity of Paget disease and the relatively young age of the patient. It was only when a CT scan of the skull was done in the course of the diagnostic work up for deafness showed a sclerotic lesion in the skull that the diagnosis of Paget disease was considered. Although Paget disease is a disease of bone, involvement of adjacent joints with damage and deformity is not uncommon, especially of the hip and knee joints, and patients may present with osteoarthritis.12,13

The fourth case was also that of a young man who presented with localized sacroiliac pain, and the initial impression was that of rheumatic or neoplastic disease. Interestingly, his initial alkaline phosphatase was normal. The diagnosis came as a surprise on biopsy. Over the next several years, the patient displayed the typical features of Paget disease, including elevated alkaline phosphatase, pain and bone enlargement. Alkaline phosphatase is an excellent marker and the most common biochemical abnormality in patients with Paget disease.14,15 It can be occasionally normal when the involved area is small or in patients who have been successfully treated.1

The cases described in this report highlight the importance of considering this diagnosis in similar cases and also suggest that Paget disease might not be that rare in Saudi Arabia, but is probably overlooked in many instances. The relatively young age of our patients is another interesting aspect that is not well explained; it may have been an accidental finding. Alternatively, it may reflect the severity of the disease in these cases, leading to their presentation at a young age. Although the exact etiology of Paget disease is unknown, previous studies suggested that genetic and environmental factors may play a role in the pathogenesis.16,17 Viral infection has been suggested to play a pathogenetic role.16–18 Particles resembling those of paramyxovirus and nucleic acid sequences of measles virus, respiratory syncytial virus and canine distemper virus have all been reported from pagetic bones. However, this issue remains controversial as results have not been consistent and complete viruses could not be isolated from pagetic bone lesions. Studies in the West and Japan showed that between 5% and 40% of patients with Paget disease report first-degree relatives with the disease. In Saudi Arabia, the rate of consanguinity is common,19 but Paget disease is considered a rare disease. In none of the four patients described in this report was there evidence of an infectious or genetic background. Although we did a bone biopsy in two of our four cases, it is generally not needed as the plain x-rays and bone scans usually suffice for the diagnosis.1,20 The two cases that had bone biopsy were unusual in their presentations, and biopsy was necessary to rule out the possibility of metastases in the first case and to characterize lesions on plain x-rays in the second case (patient 4) as the patient was young with a normal alkaline phosphate and the diagnosis of Paget disease was not a consideration at that time. Bone scintigraphy is very useful, not only in suggesting the diagnosis, but also to assess its extent and to monitor response to therapy.21 If malignancy is suspected in a pagetic lesion, MRI can be quite useful;22 and if doubt remains, biopsy should be performed.1

The majority of patients with Paget disease of bone remain asymptomatic and do not need treatment.1,20,23 Some asymptomatic patients may benefit from treatment, especially when the disease is quite active as indicated by the levels of alkaline phosphatase or other markers of bone turnover or when the bones involved are close to vital organs or bones in which the progression of the disease may lead to complications.1,20,23 Patients with significant symptoms should also be treated.14,20,24–26 Second-generation bisphosphonates have revolutionized the management of this disease.27 This is exemplified by patient 4, whose disease remained inadequately controlled for years until he received a course of high-dose alendronate, which resulted in effective long-term control of the activity of the disease.

In conclusion, we have presented four interesting cases of Saudi Arabian patients with Paget disease in whom the diagnosis was not suspected initially due to their unusual presentations and the widely held impression of the rarity of the disease in this region of the world. Although this study does not systematically assess the prevalence of the disease in the society, it suggests that this disease might not be that rare. Paget disease should taken into consideration in similar clinical situations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whyte MP. Clinical practice clinical practice.Paget disease of bone. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:593–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp060278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman R. Paget disease of the bone.2nd ed. In: Coe FL, editor. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Staa TP, Selby P, Leufkens HG, Lyles K, Sprafka JM, Cooper C. Incidence and natural history of Paget disease of bone in England and Wales. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:465–71. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle T, Gunn J, Anderson G, Gill M, Cundy T. Paget disease in New Zealand: Evidence for declining prevalence. Bone. 2002;31:616–9. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00876-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fouda M. Paget disease of the bone.A decade since the first reported case. Saudi Med J. 1998;19:447–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magen H, Liel Y, Bearman JE, Lowenthal MN. Demographic aspects of Paget disease of bone in the Negev of southern Israel. Calcif Tissue Int. 1994;55:353–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00299314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloom RA, Libson E, Blank P, Nubani N. Prevalence of Paget disease of bone in hospital patients in Jerusalem: An epidemiologic study. Isr J Med Sci. 1985;21:954–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whyte MP. Paget disease of bone and genetic disorders of RANKL/OPG/RANK/NF-kappaB signaling. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1068:143–64. doi: 10.1196/annals.1346.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paget J. On a form of chronic inflammation of bones (osteitis deformans) Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1966;49:3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins DH. Paget disease of bone; incidence and subclinical forms. Lancet. 1956;271:51–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(56)90422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siris ES. Epidemiological aspects of Paget disease: Family history and relationship to other medical conditions. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1994;23:222–5. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(94)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altman RD. Musculoskeletal manifestations of Paget disease of bone. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:1121–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780231008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helliwell PS, Porter G. Controlled study of the prevalence of radiological osteoarthritis in clinically unrecognised juxta-articular Paget disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58:762–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.12.762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siris ES. Extensive personal experience: Paget disease of bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:335–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.2.7852484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eastell R. Biochemical markers of bone turnover in Paget disease of bone. Bone. 1999;24:49S–50S. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siris ES, Ottman R, Flaster E, Kelsey JL. Familial aggregation of Paget disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 1991;6:495–500. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650060511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takata S, Yasui N, Nakatsuka K, Ralston SH. Evolution of understanding of genetics of Paget disease of bone and related diseases. J Bone Miner Metab. 2004;22:519–23. doi: 10.1007/s00774-004-0518-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basle MF, Fournier JG, Rozenblatt S, Rebel A, Bouteille M. Measles virus RNA detected in Paget disease bone tissue by in situ hybridization. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:907–13. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-5-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.el-Hazmi MA, al-Swailem AR, Warsy AS, al-Swailem AM, Sulaimani R, al-Meshari AA. Consanguinity among the Saudi Arabian population. J Med Genet. 1995;32:623–6. doi: 10.1136/jmg.32.8.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selby PL. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Paget disease: A UK perspective. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:P92–3. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.06s217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fogelman I, Carr D, Boyle IT. The role of bone scanning in Paget disease. Metab Bone Dis Relat Res. 1981;3:243–54. doi: 10.1016/0221-8747(81)90040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundaram M, Khanna G, El-Khoury GY. T1-weighted MR imaging for distinguishing large osteolysis of Paget disease from sarcomatous degeneration. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30:378–83. doi: 10.1007/s002560100360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takata S, Hashimoto J, Nakatsuka K, Yoshimura N, Yoh K, Ohno I, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of Paget disease of bone in Japan. J Bone Miner Metab. 2006;24:359–67. doi: 10.1007/s00774-006-0696-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devogelaer JP, Bergmann P, Body JJ, Boutsen Y, Goemaere S, Kaufman JM, et al. Management of patients with Paget disease: A consensus document of the Belgian Bone Club. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1109–17. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0629-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowenthal MN, Alkalay D, Abu Rabbia Y, Liel Y. Paget disease of bone in Negev Bedouin: Report of two cases. Isr J Med Sci. 1995;31:628–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyles KW, Siris ES, Singer FR, Meunier PJ. A clinical approach to diagnosis and management of Paget disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1379–87. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.8.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langston AL, Campbell MK, Fraser WD, Maclennan GS, Selby PL, Ralston SH. Randomised trial of intensive bisphosphonate treatment versus symptomatic management in Paget disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:20–31. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]