Abstract

Propolis, also known as bee glue, is a substance collected by worker bees and it is used as a material for constructing and maintaining their beehives. It has been used topically and orally by humans for its anti-inflammatory properties. However, the growing use of propolis has been paralleled by reports of allergic contact dermatitis as a reaction to the substance. Contact dermatitis with generalized cutaneous manifestations elicited by propolis ingestion has not been previously reported. Here we report on the first case of systemic contact dermatitis from propolis ingestion in a 36-year-old woman.

Keywords: Allergic contact dermatitis, Bee glue, Propolis, Systemic contact dermatitis

INTRODUCTION

Propolis is a resinous material collected from trees, and it is increasingly being used in cosmetic and medicinal preparations as an herbal remedy. Products containing propolis are marketed in various oral forms such as tablets, toothpastes, gargles, syrups and lozenges. However, adverse reactions due to propolis ingestion have been reported and these include allergic contact cheilitis, stomatitis, perioral eczema, labial edema, oral pain and dyspnea1. As these products are increasingly being used for many purposes, the potential adverse consequences should be closely examined.

CASE REPORT

A 36-year-old woman presented with severely pruritic, multiple, erythematous papules, patches and edema of the face, neck, arms, abdomen and thighs. Before the cutaneous eruption, the patient had been ingesting propolis solution as a natural tonic for a few weeks (Fig. 1). She had obtained the propolis solution from a beekeeper. The cutaneous examination revealed swollen erythematous papules and patches on the face, neck, abdomen and thighs, and marked erythematous swelling with oozing and crusting on the bilateral forearms (Fig. 2). The patient denied she had made any changes of using medicinal or cosmetic products such as hair dye and fragrances. The past history and family history revealed no specific findings except for the use of a propolis ointment on the patient's hands seven years ago. The patient did not recall any adverse effects at that time.

Fig. 1.

The propolis solution ingested by the patient.

Fig. 2.

(A) Erythematous patches and swelling on the face and (B) erythematous swelling with oozing and crusting on the forearms.

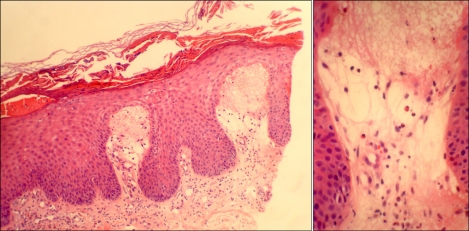

A skin biopsy was performed from the patient's left forearm lesion. The histopathological findings revealed spongiosis with marked crust, edema of the papillary dermis with vascular dilation and perivascular infiltration of eosinophils and lymphocytes (Fig. 3). The findings were consistent with contact dermatitis. The cutaneous lesions improved after four weeks of applying topical steroids and the oral administration of steroids and antihistamines. After a washout period of four weeks following the complete healing of the skin eruptions, a patch test with propolis (as is and also as 10% propolis in petrolatum) and using the standard Korean series was performed. The patient had an extreme positive patch-test reaction to propolis as is and the 10% propolis in petrolatum (both+++) at the 48-hour and 96-hour readings (Fig. 4). The patient showed a strong positive reaction to the 4-phenylenediamine base (++) and doubtful reactions (faint erythema only) to nickel sulfate (?+), colophony (?+), balsam of Peru (?+) and fragrance mix (?+). The visual scoring of the patch test readings was performed according to the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group (ICDRG) criteria.

Fig. 3.

Spongiosis, edema of the papillary dermis with vascular dilation and a perivascular infiltration of eosinophils and lymphocytes (H&E, ×100, ×400).

Fig. 4.

A patch test to propolis showed an extreme positive reaction (+++) on the 96-hour-reading.

DISCUSSION

The term "propolis" is derived from two Greek words "pro" and "polis", which mean "before" and "city", respectively. This term connotes the fact that honeybees use propolis to seal the openings of their beehives or "cities"1. Propolis is a substance brought together by worker bees from the resin of trees and flowers, and this is mixed with wax to construct and maintain their hives2. Beeswax is different from propolis in that beeswax is a secretion produced by the bees.

Propolis has been used in traditional medicine for its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiseptic and local anesthetic properties. Greeks and Romans reported on the natural products of bees other than honey and wax1,2. Records from the twelfth century describe using medicinal preparations with propolis for treating mouth and throat infections3. Today many consumers prefer 'natural products' such as propolis, and they consider them to have fewer side effects4. This trend has resulted in propolis being produced in diverse forms, including pharmaceutical and cosmetic products. Propolis is sold in many health food stores in pill forms, lozenges, cough syrups, toothpastes, gargles, shampoos, ointments, lotions and cosmetics2.

Propolis is a lipophilic, resinous substance. The composition of propolis depends on which trees the worker bees collect the resins from. Resins account for about 55% of propolis and these resins consist of free aromatic acids, for example, benzoic, caffeic, cinnamic, coumaric and ferulic acids. The main sensitizers of propolis are 3-methyl-2-butenyl caffeate and phenylethyl caffeate. Benzyl salicylate and benzyl cinnamate are less frequent sensitizers. Other compounds found in propolis such as flavonoids, beeswax, essential oils, fatty acids and pollen have shown limited sensitization capabilities5,6.

Propolis is included in the European Standard patch test series; 1.2% to 6.6% of the patients undergoing patch testing are sensitive to propolis. The recommended patch test concentration is 10% propolis in petrolatum2. Although 3-methyl-2-butenyl caffeate is the most potent sensitizer, it is not reproduced synthetically and so it is not used in the patch tests. Thirteen compounds of propolis are also found in balsam of Peru, a commonly reported allergen7. Thus, some propolis-sensitive patients show a positive reaction to balsam of Peru.

The increase in the use and popularity of propolis-containing products has been paralleled by the linear increase in the frequency of propolis-related allergic contact dermatitis. Originally, contact allergy to propolis was mostly reported in people with occupational exposure, yet most of the current cases are the result of the use of propolis-containing products that are either applied topically or ingested orally8. Ingested propolis has resulted in allergic contact cheilitis, stomatitis, perioral eczema, labial edema, oral pain and dyspnea2. However, contact dermatitis with a generalized cutaneous manifestation after the oral ingestion of propolis has not been previously reported. Propolis-induced systemic contact dermatitis was likely as the cutaneous eruption in our patient developed in response to the systemic exposure to propolis. Systemic contact dermatitis can be elicited by transepidermal, subcutaneous, intravenous, intramuscular or oral exposures9. Systemic contact dermatitis caused by food has been described, including several cases of systematically-induced contact dermatitis from aromatic substances and balsam of Peru10.

As propolis is commonly used in cosmetic and medicinal preparations, dermatologists should be aware of this important sensitizer. Obtaining a careful history and specifically the use of propolis-containing products should be done when allergic contact dermatitis is suggested without any suspected contact history.

References

- 1.Münstedt K, Hellner M, Hackethal A, Winter D, von Georgi R. Contact allergy to propolis in beekeepers. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2007;35:95–100. doi: 10.1157/13106776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walgrave SE, Warshaw EM, Glesne LA. Allergic contact dermatitis from propolis. Dermatitis. 2005;16:209–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golder W. Propolis. The bee glue as presented by the Graeco-Roman literature. Wurzbg Medizinhist Mitt. 2004;23:133–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SY, Lee DR, You CE, Park MY, Son SJ. Autosensitization dermatitis associated with propolis-induced allergic contact dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:458–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JE, Shin H, Ro YS. A case of allergic contact dermatitis to propolis on the lips and oral mucosa. Korean J Dermatol. 2009;47:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valsecchi R, Cainelli T. Dermatitis from propolis. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;11:317. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1984.tb01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hausen BM, Evers P, Stuwe HT, Konig WA, Wollenweber E. Propolis allergy (IV). Studies with further sensitizers from propolis and constituents common to propolis, poplar buds and balsam of Peru. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;26:34–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1992.tb00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giusti F, Miglietta R, Pepe P, Seidenari S. Sensitization to propolis in 1255 children undergoing patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:255–258. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nijhawan RI, Molenda M, Zirwas MJ, Jacob SE. Systemic contact dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veien NK. Ingested food in systemic allergic contact dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:547–555. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(97)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]