Abstract

Insects play a major role as vectors of human disease as well as causing significant agricultural losses. Harnessing the activity of customized homing endonuclease genes (HEGs) has been proposed as a method for spreading deleterious mutations through populations with a view to controlling disease vectors. Here, we demonstrate the feasibility of this method in Drosophila melanogaster, utilizing the well-characterized HEG, I-SceI. In particular, we show that high rates of homing can be achieved within spermatogonia and in the female germline. We show that homed constructs continue to exhibit HEG activity in the subsequent generation and that the ectopic homing events required for initiating the strategy occur at an acceptable rate. We conclude that the requirements for successful deployment of a HEG-based gene drive strategy can be satisfied in a model dipteran and that there is a reasonable prospect of the method working in other dipterans. In characterizing the system we measured repair outcomes at the spermatogonial, spermatocyte, and spermatid stages of spermatogenesis. We show that homologous recombination is restricted to spermatogonia and that it immediately ceases when they become primary spermatocytes, indicating that the choice of DNA repair pathway in the Drosophila testis can switch abruptly during differentiation.

WHILE the majority of insect species are benign insofar as human society is concerned, a few species contribute disproportionately to human morbidity and agricultural losses. Such deleterious insect populations have been the targets of control efforts for a considerable time. Control measures can have either a transient or a sustained mode of action. Transient control measures include the use of pesticides, removal of insect habitat, and inundative release strategies such as the irradiated sterile insect technique (SIT). These measures are expected to have an immediate effect on population size but require repeated, large-scale application if population suppression is to be maintained at acceptable levels. For example, SIT requires the breeding and release of insects totaling several times the resident population size, posing serious logistical problems in terms of breeding and distribution. Similarly, the widespread distribution and use of pesticides pose logistical, safety, and environmental problems even if the ever-present problem of pesticide resistance is ignored.

More recently, interest has turned to gene drive strategies that have the potential for a sustained reduction in the targeted population (reviewed in Sinkins and Gould 2006). Gene drive systems utilize selfish genetic elements to drive a trait through the target insect population, where the trait in question may be deleterious, e.g., sterility, or relatively benign, like resistance to carriage of a parasite or virus. The advantages are immediately apparent: such strategies allow for a smaller release population since the frequency of the selfish element is expected to grow in the population. In addition, a selfish element could potentially have persistent negative impacts on the target population. Finally, the ability of selfish elements to spread allows effects that are distant from the site of release, a characteristic that is very useful when the target area is inaccessible owing to infrastructure or human conflict. However, gene drive strategies are not without problems. One major issue is the difficulty in maintaining the association between the trait of interest and the selfish genetic element, especially if a transcription unit within the selfish genetic element confers the trait. For example, if a gene conferring resistance to a parasite is introduced into a selfish genetic element and is subsequently mutated and inactivated, copies of that resistance gene will continue to be driven into the population, possibly in competition with functional copies. Further, even if the gene drive is successfully implemented, its ability to spread also poses a risk should the engineered selfish element be discovered to have unexpected and undesirable side effects. We present our investigations into the feasibility of deploying a drive strategy that uniquely possesses the facility for recall; i.e., the introduced element can be driven from the population by a specially crafted element (Burt 2003). It also has the advantage that since the trait of interest is most frequently generated by insertion of the driver, the trait and the driving mechanism are not easily dissociated.

Homing endonuclease genes (HEGs) act as selfish genetic elements in prokaryotes and lower eukaryotes (reviewed in Burt and Trivers 2005). In a diploid organism carrying a HEG insertion on one of the homologous chromosomes, the activity of the HEG will generate a double-strand break (DSB) on the wild-type homolog. Subsequent repair of the break by homologous recombination (HR), using the HEG-containing chromosome as template, causes the HEG to be copied over such that the HEG “homes” into the homologous position on the wild-type chromosome (Figure 1A). It has been suggested that the homing activity of HEGs provides a mechanism for genetically manipulating natural populations and could therefore offer a means of insect disease vector control (Burt 2003). In this scheme, a HEG is engineered to recognize and cleave a sequence within a target gene: a donor chromosome is constructed in which the target site is interrupted by the insertion of a transcription unit expressing the engineered HEG in the germline. Homing of the HEG in an individual heterozygous for the donor and a wild-type chromosome will cause loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in the germline and all gametes arising from that cell will thereafter bear the HEG (Figure 1B). The resulting non-Mendelian inheritance drives the HEG through the population even when the insert may have deleterious effects on the host (Figure 1C).

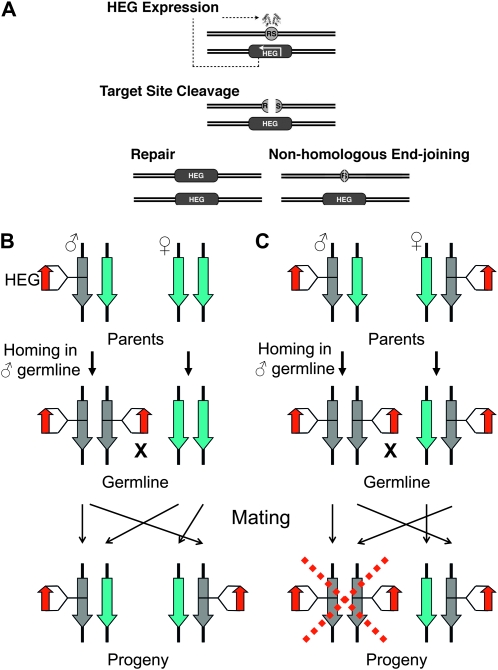

Figure 1.—

The HEG strategy. (A) In an animal trans-heterozygous for a HEG-containing chromosome, transcription and translation of the HEG in the germline produce an active nuclease. The enzyme makes a DSB at its recognition sequence (RS) on the target. Repair of the DSB can be by the desired homologous recombination route, converting the target chromosome to a HEG-containing donor, or by an undesirable nonhomologous end-joining event. (B) The population control strategy is illustrated by considering a HEG transgene inserted into and disrupting a target gene that it homes with 100% efficiency in the male germline. It is further assumed that the target gene is recessive lethal because it plays an essential somatic role but is not required for fertility. When a male trans-heterozygous for the transgene is mated to a wild-type female, the HEG homes onto its homologous chromosome in the germline. The animal remains viable as somatic tissues remain heterozygous for the HEG insertion; however, all gametes from the male now bear the HEG insertion. As a consequence, all progeny from this mating will be heterozygous for the HEG insertion, thereby increasing the frequency of this insertion within the population. (C) In the event of two heterozygotes mating, all sperm from the male carry the HEG insertion while only half of the oocytes do. Half of the progeny will be homozygous for the HEG insertion-disrupted gene and therefore inviable while the remaining progeny are heterozygous for the HEG insertion and available to further propagate the HEG insertion.

There are two main requirements for the success of the engineered HEG strategy. First, homing must occur in a metazoan. To date, all examples of homing have been observed in unicellular organisms and no genes resembling HEGs have been found in any metazoan genome (e.g., see Burt and Trivers 2005). One possible reason could be that efficient HR is excluded from the germline. In Drosophila, two previous studies investigated HR in the male germline with very different results. Rong and Golic reported that HR constitutes up to 65% of repair events while Preston and co-workers, using a superficially similar assay, found HR to be used in <19% of repaired lesions (Rong and Golic 2003; Preston et al. 2006b). Establishing an accurate estimate of the rate of HR that can be achieved in the germline is therefore important since this repair pathway is critical to the success of the HEG strategy. In addition, to effectively initiate the HEG strategy, a HEG must be precisely inserted at the cleavage site within its host target gene, for example through repair of the cleavage from an ectopic template containing the HEG insert at a nonhomologous site.

Since transgenesis is a nontrivial technique in most insect systems, we modeled the feasibility of the HEG strategy in the tractable dipteran, Drosophila melanogaster, for which highly developed genetic tools are available. We show that homing can be achieved from both the homologous site and an ectopic site in the Drosophila genome, suggesting that the HEG-based strategy may be adaptable to insects such as anopheline mosquitoes, which pose a considerable health threat to human populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production of transgenics:

The target construct, pDarkLime, is a derivative of pBac[3xP3-eGFPafm] from which superfluous sequences were removed, an I-SceI target site was inserted into the GFP ORF, and an attB site for φC31 recombination was added (Horn and Wimmer 2000). The I-SceI target site in pDarkLime was converted into a NotI site with an adaptor to yield pDarkLime-NotI. wDarkLime has the mini-white gene inactivated by a frameshift introduced into an internal NcoI site. pLemon is similar to pDarkLime except that an imperfect repeat of the I-SceI target site rendered the GFP ORF out-of-frame.

Promoter fragments were obtained by PCR from the sequenced y;cn bw sp strain and inserted into the pYSC10 (HEG-1 design) or the pXSceI (HEG-2 design) I-SceI cassettes. pYSC10 comprises the I-SceI ORF (Rouet et al. 1994) and Hsp70Ab 3′-UTR fragment from 70I-ISceI cloned downstream of the pBluescript polylinker. pXSceI contains the I-SceI ORF downstream of the pBluescript polylinker. In both cases, NotI digestion releases the promoter/I-SceI fusion for cloning into the NotI site of the appropriate mini-white–marked transformation plasmid. HEG-1-based constructs are inserted directly into the pDarkLime-NotI construct (described as “donor template” in Figure 2). HEG-2–based constructs are inserted into a variant of pDarkLime-NotI in which RFP (Campbell et al. 2002) and the appropriate 3′-UTR were already assembled. See Figure 2 for schematics of both constructs.

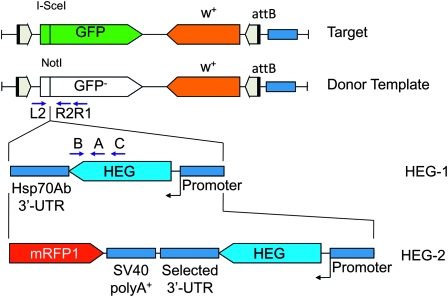

Figure 2.—

Schematics (not to scale) of the constructs used in this study. An in-frame I-SceI recognition site was inserted into the GFP reporter ORF to create the target construct. The donor template was created by inserting a NotI site at the I-SceI cleavage site to permit the insertion of HEG transcription units. The positions of the eGFP-L2, eGFP-R2, eGFP-R1, ISceI-A, ISceI-B, and ISceI-C primers are marked L2, R2, R1, A, B, and C, respectively on the schematics. Flanking P- and piggyBac transposon ends are shown as gray arrowheads. The attB site used for φC31 recombination is shown as a light blue block. Further details are in materials and methods.

Transgenic lines were produced by φC31-integrase–mediated insertion (Groth et al. 2004) using integrase mRNA produced with the mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion). Donor lines were inserted in an attP1 stock marked with black or an attP2 stock marked with curled; targets were inserted into unmarked versions of the same stocks.

Fluorescence microscopy:

GFP status of the flies was scored with a Leica MZ16F fluorescence microscope with the GFP2 and TXR filter sets.

RNA in situ hybridization:

The protocol used was essentially as published (Morris et al. 2009) except that we used digoxigenin-labeled single-stranded DNA probes generated by asymmetric PCR of an I-SceI coding sequence with primers ISceI-B and ISceI-C. Both sense and antisense probes were generated from this template by asymmetric PCR with the same primers thereafter.

Crosses:

Experiments used constructs inserted into the chromosome III attP2 site (Groth et al. 2004). Trans-heterozygotes were produced with the I-SceI–expressing donor males to eliminate recombinative loss of markers and the contribution of maternal RNA to HEG activity. Crosses used to generate the trans-heterozygotes were of type <donor> cu/TM6C Sb cu × <target> from which the Sb+ cu+ progeny, <donor> cu/<target>, were selected.

The experimental crosses were performed as mass matings of ♂ y w;;attP2{aly-HEG-1} cu/attP2{pDarkLime} × ♀ y w;;attP2 cu, ♂ y w;;attP2{β-Tub85D-HEG-1} cu/attP2{pDarkLime} × ♀ y w;;attP2 cu, ♂ y w;;attP2{Mst87F-HEG-1} cu/attP2{pDarkLime} × ♀ y w;;attP2 cu, ♂ y w;;attP2{Hsp26-HEG-1} cu/attP2{pDarkLime} × ♀ y w;;attP2 cu, ♂ y w;;attP2{Hsp70-HEG-1} cu/attP2{pDarkLime} × ♀ y w;;attP2 cu, ♂ y w;;attP2{vasa-HEG-1} cu/attP2{pDarkLime} × ♀ y w;;attP2 cu, ♂ y w;;P{Act5C-P-HEG-1} cu/attP2{pDarkLime} × ♀ y w;;attP2 cu, ♂ y w;;P{bam-HEG-2} cu/attP2{wDarkLime} × ♀ y w;;attP2 cu, ♂ y w;;P{Act5C-P-HEG-2} cu/attP2{wDarkLime} × ♀ y w;;attP2 cu, and ♀y w;;P{Act5C-P-HEG-2} cu/attP2{wDarkLime} × ♂ y w;;attP2 cu, from which the cu+ progeny bearing the target chromosome, attP2{pDarkLime or wDarkLime}/attP2 cu, were selected and scored. The choice of a HEG-1 or HEG-2 backbone is indicated above in the stock name. Some of the crosses were initially scored using pDarkLime and subsequently reassessed with wDarkLime to improve the counts. HEG-1 progeny were scored by PCR while HEG-2 progeny were scored by GFP and RFP fluorescence.

Ectopic homing was assessed by crosses of ♂ y w; attP1{pDarkLime}/+;attP2{vasa-HEG-2} cu/+ × ♀ y w;;attP2 cu and ♂ y w; attP1{pDarkLime}/+;attP2{act5C-P-HEG-2} cu/+ × ♀ y w;;attP2 cu. Progeny bearing the target chromosome were identified as w+ cu+ and ectopically homed candidates identified as RFP positive.

PCR analysis of repair outcomes:

DNA was prepared from single flies by maceration in a microfuge tube with a micropipette tip. The positions of primers used for PCR are shown in Figure 2. In HEG-1–based crosses, flies were sorted by GFP status. GFP-negative pDarkLime-bearing progeny were then screened by PCR across the I-SceI target sequence with primers eGFP-L2 and eGFP-R2 (Figure 3, A and B, marked X). When product X was present, that target was scored as repaired by nonhomologous end joining out-of frame (NHEJ-o) (Figure 3B, top, lane 4). The absence of product could be attributed to either the disruption of the site by a homed insert (Figure 3B, top, lanes 1 and 2) or a larger NHEJ deletion (see below). Homing was detected by PCR across the junction between the homed insert and the pDarkLime target, using eGFP-L2 and primer (ISceI-A) within the I-SceI coding sequence (Figure 3A, span marked Y). Only homed targets are expected to have product Y (Figure 3B, bottom, lanes 1 and 2). Large NHEJ-o deletions are negative for both products X and Y while retaining b or cu from the target chromosome (Figure 3B, lane 3). GFP-positive progeny were occasionally screened with a PCR assay across the target site (Figure 3C) and the products examined for the integrity of the I-SceI target site by digestion with I-SceI to distinguish uncut targets from NHEJ in-frame (NHEJ-i) events. Intact targets are cleaved and show reduced fragment size (Figure 3C, lanes 1 and 5) compared with NHEJ-i events (Figure 3C, lanes 2–4). We amplified and sequenced DNA from a number of flies scored as NHEJ-i and NHEJ-o events. The results confirmed that our assay was usually accurate with several representative sequences shown in Figure 3D.

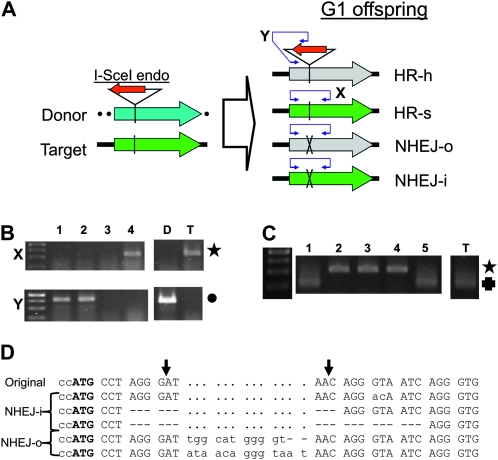

Figure 3.—

Assays used in classifying repair products. (A) The experimental cross juxtaposes the I-SceI donor construct with the pDarkLime target at homologous sites. Expression of the I-SceI endonuclease (red) inserted into the donor construct (marked cyan) causes cutting of the pDarkLime target (marked green) at the I-SceI site (vertical bar) within the GFP ORF. This DSB is then repaired to yield a variety of products depending on the repair pathway. Products also depend on whether the repair template was the homologous chromosome or the sister chromatid. NHEJ can yield in-frame (NHEJ-i) or out-of-frame (NHEJ-o) products (destruction of the I-SceI target site is indicated by a cross). The status of the GFP reporter gene is indicated by its color, with active GFP product indicated by green. Repair products are identified with two PCR assays, one across the I-SceI cleavage site using eGFP-L2 and eGFP-R2 (marked X; 567 bp) and another across the junction between the I-SceI gene and the eGFP target using eGFP-L2 and I-SceI-CDS-R3 (marked Y; 780 bp). (B) Products of PCR screening assays: lanes 1 and 2 are derived from progeny in which homing has occurred. Lanes 3 and 4 are derived from large and small NHEJ-o deletions, respectively. Lanes D and T represent the results obtained from donor and target stock DNA controls, respectively. Top: results of PCR assay X (see above). Product X is absent when either a HEG insertion is present as in HR-h or an NHEJ-o deletion has removed one or both primer binding sites (lanes 1–3). The size expected of product X is marked with a star to the right. Bottom: results of PCR assay Y (see above). Only the donor stock and homed products yield PCR product Y (lanes 1 and 2). The expected size of product Y is marked with a solid circle to the right. Samples in which both products X and Y are absent are scored as large NHEJ deletions (lane 3). The DNA ladder has 250-, 500-, 750-, and 1-kb bands. (C) Identification of NHEJ-i products: lanes 1–5 are associated with GFP-positive progeny bearing the target construct. Lane T is a positive control from a stock containing an intact target site. DNA from these stocks were subjected to PCR assay X and the products subsequently digested with I-SceI. Products from uncut targets should remain susceptible to I-SceI digestion (lanes 1 and 5) while NHEJ-i products are refractory to this treatment (lanes 2–4). The star and cross mark the expected sizes of the uncut fragment and I-SceI–digested fragments. The DNA ladder has 250-, 500-, 750-, and 1-kb bands. (D) Sequences of NHEJ-i and NHEJ-o junctions: the top line shows the sequence of the I-SceI target site in eGFP organized as codons with the initiation codon marked in boldface type. Vertical arrows mark the extent of the overhang generated by I-SceI cleavage. Rows 2–4 show sequences recovered from progeny scored as having undergone NHEJ-i. Row 2 shows two changed bases abolishing the I-SceI recognition site while rows 3 and 4 show 9- and 18-base in-frame deletions, respectively. Rows 5 and 6 were obtained from progeny scored as NHEJ-o events. They show frameshift-inducing insertions of 11 and 13 bases, respectively. Flies used in this experiment were obtained from crosses using Act5C-P-HEG–bearing trans-heterozygote males.

Calculation of effective cutting and homing rates:

In our statistical model, the fraction of target chromosomes in progeny repaired by HR-h and NHEJ are pHR-h and pNHEJ, respectively, and the effective cutting rate is then pcut = pHR-h + pHR-h. As the product of HR-s is indistinguishable from the uncut chromosome, this analysis excludes the contribution of HR-s altogether. NHEJ-i–repaired chromosomes can be distinguished from uncut/HR-s chromosomes only by recovering the target site by PCR and subsequently testing its integrity by I-SceI digestion. The scale of our experiments precluded PCR/I-SceI digestion of every target chromosome; therefore we determined the ratio of NHEJ-o:NHEJ-i by molecular analysis of ~200 chromosomes to be 2.6:1 and used this to account for NHEJ-i cases with the fraction of NHEJ chromosomes repaired out-of-frame, pNHEJ-o, set at 0.722. Then, GFP loss, or the fraction of target chromosomes that are GFP negative, is pGFP− = pHR-h + pNHEJ-opNHEJ. Similarly, the fraction of cleaved chromosomes resolved by HR-h (homing fraction in Table 1), phome, is pHR-h/pcut. The fraction of GFP-negative chromosomes that are also homed, pHEG, is pHR-h/pGFP−. Then, the probability of a particular combination of pHR-h and pNHEJ yielding the observed numbers of GFP-negative and homed targets can be calculated using the binomial distribution with the derived values of pGFP− and pHEG. The posterior distribution of pHR-h and pNHEJ was then estimated by a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) procedure with the mcmc package (version 0.8, by Charles J. Geyer) in the R environment (R Development Core Team 2010). One thousand samples from the posterior distribution, spaced 1000 iterations apart, were used to derive the means and standard deviations of pcut and phome. A uniform prior was assumed.

TABLE 1.

Summary of results of study

| Construct | Promoter (extent)a | 3′-UTR | Design | GFP loss (counts)/effective cutting rated | Homing fractione (counts) | Expressionf | References |

| aly | aly (−875:+97) | Hsp70Ab | HEG-1 | 38% (417/1094) 49 ± 2% | 2 ± 1% (2/94) | SC | Wang and Mann (2003) |

| β-Tub85D | β-Tub85D (−188:+230) | Hsp70Ab | HEG-1 | 70% (688/985) 90 ± 2% | 2 ± 1% (1/94) | SC, SP | Michiels et al. (1989) |

| Mst87F | Mst87F (−551:+240) | Hsp70Ab | HEG-1 | 61% (638/1041) 79 ± 2% | 1 ± 1% (0/94) | SP | Kuhn et al. (1988) |

| Hsp26 | Hsp26 (−499:+237) | Hsp70Ab | HEG-1 | 50% (162/322) 63 ± 4% | 11 ± 3% (12/94) | SC | Glaser et al. (1986); Glaser and Lis (1990) |

| Hsp70 | Hsp70b | Hsp70Ab | HEG-1 | 26% (78/296) 28 ± 3% | 74 ± 3% (225/287) | HS induction | Rong and Golic (2003) |

| Act5C-P (males) | Act5C/P-intron | Hsp70Ab | HEG-1 | 6% (44/793) 7 ± 1% | 29 ± 6% (15/44) | Germline | Laski et al. (1986); Bond-Matthews and Davidson (1988); Laski and Rubin (1989) |

| vasa | vasa (−234:)c | β-Tub56D | HEG-2 | 33% (1234/3764) 38 ± 2% | 36 ± 1% (523/1234) | Germline | Hay et al. (1988); Sano et al. (2002) |

| bam | bam (−169:+186) | β-Tub56D | HEG-2 | 9% (357/3910) 10 ± 1% | 63 ± 3% (245/357) | SG | Gonczy et al. (1997); Chen and Mckearin (2003) |

| Act5C-P (males) | Act5C/P-intron | β-Tub56D | HEG-2 | 53% (671/1272) 62 ± 2% | 32 ± 2% (252/671) | Germline | Laski et al. (1986); Bond-Matthews and Davidson (1988); Laski and Rubin (1989) |

| Act5C-P (females) | Act5C/P-intron | β-Tub56D | HEG-2 | 35% (937/2685) 39 ± 1% | 50 ± 2% (526/937) | Germline | Laski et al. (1986); Bond-Matthews and Davidson (1988); Laski and Rubin (1989) |

The combined data from our experiments are summarized here. Estimates of the effective cutting rate and homing fraction after accounting for NHEJ events were obtained by MCMC using the mcmc package (C. J. Geyer) written in R (R Development Core Team 2010).

All extents are measured with the transcriptional initiation site in FlyBase as +1.

As used in 70I-ISceI in Rong and Golic (2006). Heat-shock induction was applied.

Complete spliced 5′-UTR included.

Fraction of target chromosomes cut (excluding sister chromatid repair events), corrected for NHEJ-o events. Standard deviation of the estimate is also provided.

Fraction of repaired chromosomes exhibiting a homed insert. Standard deviation of the estimate is also provided.

SC, spermatocyte; SG, spermatogonia; SP, spermatid.

Act5Cinit and mRFPstop were originally used during the assembly of constructs and were repurposed later as diagnostic primers. Primer sequences are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primer sequences

| eGFP-L2 | GCA CGG TTC CCA CAA TGG T |

| eGFP-R1 | GCC GGA CAC GCT GAA CTT GT |

| eGFP-R2 | GTC GTG CTG CTT CAT GTG GT |

| ISceI-A | TCG ATC GTA CTG AAC ACC CAG T |

| ISceI-B | GGG ATC AGG TAC GGT TTG ATC AG |

| ISceI-C | CCA CCT GGG TAA CCT GGT |

| mRFPstop | GGG GCG GCC GCT TAG GCG CCG GTG GAG TG |

| Act5Cinit | GGG CAT TTT GTA AGG GAA TGA CTG GAA TAA ACC GAC TGA |

| EcoRI-A | TCC CAG CGG CTG TAC TG |

| EcoRI-B | GCA GCT GGC ACG |

RESULTS

Development of a homing assay in Drosophila:

Homing requires that HEG donor and target sequences are located at homologous sites in the genome. We achieved this in Drosophila by using the φC31 system to integrate donor and target constructs carrying attB sites into chromosome 2R (attP1) and chromosome 3R (attP2) landing sites (Groth et al. 2004). We designed a primary target construct, pDarkLime, comprising an in-frame I-SceI target site within a GFP open reading frame that is expressed via the eye-specific 3xP3 promoter (“target” in Figure 2). The integrity of the target, which is also marked with the mini-white gene, is determined by GFP fluorescence in the eye with homing events from the donor indicated by loss of GFP expression. We also prepared a variant, wDarkLime, in which the mini-white marker was inactivated by a frameshift so that the GFP phenotype was not obscured by eye pigmentation.

The scaffold for our donor constructs is the pDarkLime backbone in which the I-SceI target site is replaced by a NotI site, into which I-SceI–expressing constructs can be cloned (donor template in Figure 2). We used two expression cassette designs: first a donor vector, HEG-1, derived from the 70 I-SceI construct of Rong in which the I-SceI ORF is terminated by an Hsp70Ab 3′-UTR (Rong and Golic 2003). The majority of our vectors used this construct; however, due to issues relating to HEG expression levels and identifying homed targets, we developed an improved vector, HEG-2, which replaces the Hsp70 3′-UTR with a variety of other 3′-UTRs and incorporates an RFP marker (Figure 2).

In common with previous Drosophila assays used to study DSB repair, we generated male trans-heterozygotes in which a donor construct-containing chromosome (referred to as donor hereafter) is juxtaposed with its homolog carrying a target site (Rong and Golic 2003; Preston et al. 2006a,b). The target-bearing chromosome is distinguished from the donor chromosome by a recessive marker carried on the latter and assayed in crosses with suitably marked females (the absence of recombination in male Drosophila allows tracking chromosomes in this way). Activity of the HEG can lead to a number of different outcomes (Figure 3A). When homologous recombination with the homolog occurs (HR-h), the HEG-expressing cassette in the donor is copied over to the target construct, resulting in a homing event. Homologous recombination with the sister chromatid (HR-s) results in reversion to the original uncut state, rendering the target susceptible to recutting. NHEJ can result in either NHEJ-i or NHEJ-o outcomes that can be distinguished by GFP fluorescence. The relative frequencies of each of these four outcomes can be determined by scoring the phenotype and genotype of progeny derived from trans-heterozygous males.

In our assays, both NHEJ-o and HR-h result in the loss of GFP fluorescence in the target-bearing progeny and with the HEG-1 donor these outcomes were distinguished by PCR assays for the presence of the I-SceI ORF. This was expensive and laborious, limiting the number of progeny that could be screened. The need for PCR screening was eliminated in our second series of HEG-2 vectors that mark the I-SceI expression cassette with RFP, thus allowing direct scoring of HR-h events by fluorescence microscopy. We verified that HR-h could be scored reliably with RFP alone by showing via PCR and subsequent sequencing of several RFP-positive progeny that the targets have the expected junctions created by HEG insertion (Figure 4A). NHEJ-i events cannot be directly scored by fluorescence and can be assessed only by PCR amplification of the target site from genomic DNA followed by digestion with I-SceI. Rather than assay every chromosome we indirectly accounted for the NHEJ-i rate during the calculation of effective cutting and homing efficiencies presented in Table 1 as described in materials and methods.

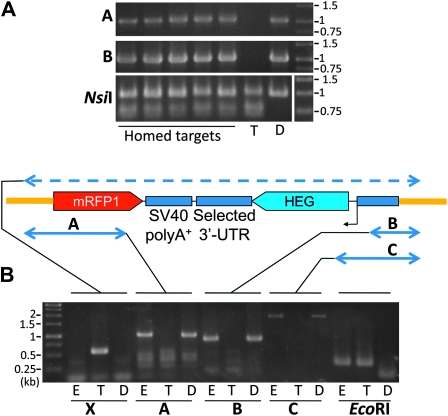

Figure 4.—

Verifying the integrity of homed inserts. The schematic shows an insert at its target position (not to scale), flanked by the target transgene backbone (thick orange line). Double-headed arrows show the spans targeted for amplification for each PCR assay. (A) PCR analysis of several presumptive HR-h events identified by RFP fluorescence. Top and middle: five candidate HR-h events arising from Act5C-P-HEG/wDarkLime trans-heterozygotes were analyzed for the presence of insert-target junctions with PCR assays A (top, primers mRFPstop to eGFP-L2) and B (middle, Act5Cinit to eGFP-R2). PCR product A spans the left junction between the mRFP1 ORF within insert and the sequence flanking the target site and should yield an ∼1-kb product with an intact left junction at the I-SceI target site—this should occur only with the donor and the homed targets. Product B spans the right junction between the Act5C promoter and the target and should produce an 883-bp product only when the insert is present and has an intact right junction—a product is therefore expected with homed targets and the donor only. The spans of these products are marked A and B, respectively, in the schematic. Bottom: the presence of the target construct was independently verified by amplifying the neighborhood of a NsiI polymorphism within the mini-white marker. wDarkLime targets possess an NsiI site created in the course of ablating w activity. PCR amplification of the wDarkLime mini-white marker yields a product that is cleavable on subsequent NsiI digest (lower band is cleavage product) whereas amplification of w either on the host chromosome or within the donor construct yields an uncleavable product (top band). As expected, only the target negative control and homed targets show evidence of NsiI cleavage. Negative and positive controls used DNA from the target and donor construct-carrying stocks (marked T and D, respectively). (B) PCR analysis of an ectopically homed Act5C-P-HEG insert. E, T, and D denote the ectopically homed, target, and donor stocks, respectively. Each group of lanes is marked below with X, A, B, C in boldface type to indicate the PCR reaction used to regenerate the product. The previously described PCR product X spans the I-SceI target site and, as expected, yields only the expected 567-bp band with the target stock (T). Products A and B are, as expected, present only in the donor and homed stocks. Product C (ISceI-B to eGFP-R1) is another test for right junction integrity, from the I-SceI ORF, spanning the Act5C promoter into the right flanking sequence within eGFP. Both the donor and the ectopically homed stock, but not the target, should yield ∼2-kb fragments. Finally, we amplified (with EcoRI-A and -B), and subsequently subjected to EcoRI digest, the region flanking a polymorphic EcoRI site that is cleavable only in the donor construct. The results demonstrate that the ectopically homed stock has a target construct backbone only and the above results do not originate from contamination by donor sequences. The EcoRI site, which is immediately to the right of the attB site in Figure 2, lies 3.4 kb left of the I-SceI target site when integrated in the genome through φC31 recombination at attB.

A further qualification is that our cutting and homing efficiencies are calculated on the basis of the fraction of progeny bearing the characteristics of particular repair events. As previously observed, this fraction is correlated with, but not synonymous with the fraction of repair events arising from a particular repair mechanism (Preston et al. 2006b). A repair event in a cell at an early stage of spermatogenesis will be replicated and be represented in multiple offspring. As a consequence, the fraction of progeny that arise through repair by a mechanism favored during early spermatogenesis will be exaggerated in comparison to the fraction of repair events in which it was actually involved. However, for the purposes of a HEG-based population control strategy, it is the proportion of progeny in which HEG transmission occurs that is important and we therefore consider the use of statistics based on progeny counts as justified in this case.

Homing can occur in Drosophila:

Previous studies in Drosophila indicate that up to 11 kb of DNA can be efficiently copied by HR-h repair of P-element–induced DSBs, suggesting it is feasible that an entire transcription cassette containing a HEG could be copied during repair (Johnson-Schlitz and Engels 2006). To test for homing we utilized the Hsp26-HEG containing a 1.8-kb transcription cassette. When Hsp26-HEG/pDarkLime trans-heterozygotes are tested for HEG activity in the absence of heat-shock induction, ∼50% of the target chromosomes lose GFP fluorescence as a consequence of Hsp26-driven I-SceI expression (Table 1). When the GFP-null progeny were assayed for the presence of the I-SceI gene by PCR, ∼13% were positive (equivalent to 11% of repaired chromosomes when NHEJ-i progeny are accounted for), demonstrating that homing can occur in a metazoan system.

We wished to confirm that HEGs inserted into a chromosome by homing continue to express I-SceI activity. To this end we isolated 5 homed Hsp26-HEG/TM6C males and individually crossed these to another target stock, pLemon, which is almost identical to pDarkLime except that the GFP ORF is frameshifted in the vicinity of the I-SceI site and the flies are phenotypically GFP−. In the presence of HEG activity, NHEJ-o will occasionally revert the GFP frame: this was observed with the Hsp26-HEG homed males. We repeated this test with a further 12 individuals that received homed HEG insertions from act5C-P-HEG. With both these HEG donors all of the homed progeny continued to home when presented with fresh targets. Finally, we selected a homed individual derived from the vasa-HEG donor and conducted a full-scale homing assay on it. We obtained a GFP loss of 35% (269/775) compared to 33% for the original donor (1234/3764) and identified 94 RFP positives from the 775 target chromosomes derived from the homed stock compared with 523 RFP positives from 3764 target chromosomes from the original stock. Neither of these differences is statistically significant. We believe this to be the first unequivocal demonstration of homing in a metazoan system.

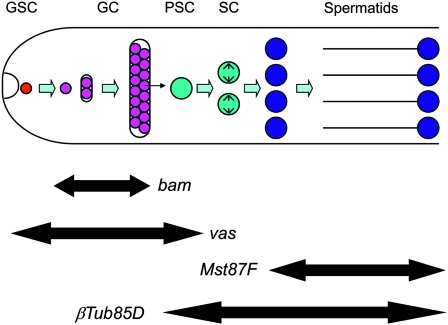

Design and production of transgenics targeting different spermatogenetic stages:

Spermatogenesis begins with the asymmetric division of the germline stem cell (GSC), regenerating itself and a primary spermatogonium. The primary spermatogonia undergo four rounds of incomplete division to yield 16 spermatogonia linked by ring canals. These spermatogonia then enlarge and differentiate into primary spermatocytes, which undergo a long maturation before completing meiosis, forming the 64 spermatid precursors of mature spermatozoa (Figure 5). Efficient homing requires a high HR-h rate and a relatively low NHEJ rate, with the balance between these repair processes believed to dependent on the tissue and stage of development (Preston et al. 2006a,b). Consequently, the effect of generating chromosomal breaks at different stages during spermatogenesis was of considerable interest. To assay this, we produced a set of transgenic fly lines carrying different donor constructs in which I-SceI expression is controlled by a set of promoter/enhancer regions known to be active at different stages of male germline development, ranging from sequences active from early embryonic stages to those that are restricted to relatively late stages of spermatogenesis (see Table 1). vasa expression begins in the primordial germ cells of the embryo and continues to be expressed during development in GSCs through to spermatocytes (Hay et al. 1988; Sano et al. 2002). bag of marbles (bam) is repressed in the GSCs and restricted to the spermatogonial population (Gonczy et al. 1997; Kiger et al. 2000; Tulina and Matunis 2001;Chen and Mckearin 2003). Native expression from the Hsp26 promoter in the absence of heat shock is detectable in spermatocytes immediately after their differentiation from their spermatogonial precursors (Glaser et al. 1986; Glaser and Lis 1990). The Hsp26-HEG also provides a way of inducing high levels of HEG expression via heat shock. Promoters from the always early (aly) and β-Tubulin85D genes are expressed from the spermatocyte stages onward (Kuhn et al. 1988; Michiels et al. 1989; White-Cooper et al. 2000; Wang and Mann 2003). Although transcription in the Drosophila testis occurs almost exclusively prior to meiosis, with postmeiotic expression observed for a few genes (Barreau et al. 2008; Vibranovski et al. 2010), gene products required postmeiotically are typically translationally restricted to the haploid stages. To assay postmeiotic effects we used the promoter from Mst87F and also included the well-characterized Mst87F translational control element, which restricts protein expression to postmeiotic spermatids (Kuhn et al. 1988).

Figure 5.—

Drosophila male spermatogenesis. Schematic of male spermatogenesis (not to scale): male germline stem cells (GSCs, red) divide asymmetrically to yield primary spermatogonia (SG, magenta). Each of these, in turn, undergoes incomplete mitosis to yield 16 spermatogonia that are encapsulated within a cyst. Each spermatogonium differentiates into a primary spermatocyte (PSC) that expands in volume and the spermatocytes (SC, cyan) subsequently undergo meiosis to form four primary spermatids (blue) that, in turn, mature and elongate into spermatozoa. The extent of expression expected for several of the germline-specific promoters used by us is indicated with double-pointed arrows.

Earlier work by Rong and Golic, utilizing I-SceI activity for targeted homologous recombination, reported that Hsp70-driven I-SceI results in high rates of HR-h when I-SceI is induced by heat shock (Rong and Golic 2003). We therefore generated an Hsp70-HEG construct by inserting their 70I-SceI transcription unit into our donor vector to determine if it could drive HR in a homing context. All but the vasa-HEG and bam-HEG donors were based on HEG-1 constructs. The vasa-HEG and bam-HEG constructs were based on a HEG-2 design with β-Tub56D and bam 3′-UTR and termination signals, respectively. Finally, we designed a strongly expressed germline-specific construct by combining the Act5C promoter with the P-transposase germline-specific intron (Laski et al. 1986; Bond-Matthews and Davidson 1988; Laski and Rubin 1989). In this act5C-P fusion construct, the P-transposase intron was inserted in frame between the Act5C initiation codon and the I-SceI ORF such that the HEG would be successfully translated only when that intron was spliced out. The HEG expressed from this construct contains a small N-terminal extension derived from the flanking exonic sequences around this intron that are essential for its proper function (Laski and Rubin 1989).

The native pattern of testis expression of promoters is broadly maintained in I-SceI–expressing transgenic lines:

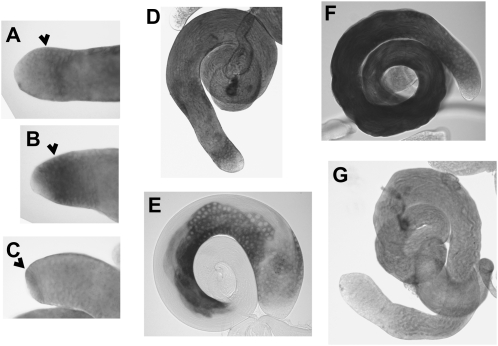

Lines derived from the Hsp26-HEG, vasa-HEG, and bam-HEG constructs are expected to be expressed at the distal end of the testis only and this was observed through RNA in situ hybridization assays (Figure 6, A–C). HEG transcripts were not detected at the extreme distal tip of the testis with these constructs. With the Hsp26-HEG construct, HEG transcription was concentrated within a band spanning the earliest primary spermatocytes, while the vasa-HEG was detected earlier, increasing expression and persisting into the spermatocytes (Figure 6, A and B). The aly-HEG construct was also expected to be expressed in primary spermatocytes but expression appears to start later than that of the Hsp26-HEG, vasa-HEG, and bam-HEG constructs (Figure 6D). The bam-HEG construct was observed to express the HEG transcript in spermatogonia (Figure 6C). The later-expressing constructs, β-Tub85D-HEG and Mst87F-HEG, showed staining in maturing spermatocytes and spermatids (Figure 6, D–F). Mst87F-HEG–derived transcripts appeared to be particularly abundant at later stages of spermatogenesis (Figure 6F).

Figure 6.—

In situ hybridization of testis from transgenic stocks. RNA in situ hybridization (Morris et al. 2009) was used to visualize I-SceI transcripts in testes from (A) Hsp26-HEG, (B) vasa-HEG, (C) bam-HEG, (D) aly-HEG, (E) β-Tub85D-HEG, and (F) Mst87F-HEG transgenics. G is a negative control lacking an I-SceI transgene. Arrowheads indicate where the probe signal is located. E and F were taken at lower magnification as the signal spanned the entire testis. The spermatogonial population could be distinguished from the spermatocytes by size. Act5C-P-HEG in situ hybridizations were not performed as HEG expression is regulated by splicing and transcript localization is not therefore informative.

Homing rates are critically dependent on timing of I-SceI expression:

We hypothesized that the high HR-h fraction observed with Hsp70-HEG is a consequence of expressing I-SceI in an HR-h–competent cellular population and set out to identify this population using the panel of donors that express I-SceI in different cell types during spermatogenesis. The results of homing assays clearly demonstrate that homing rates vary widely depending on promoter choice (Table 1). First, HR-h was extremely rare (≤2% of repaired target chromosomes) using the aly-HEG, β-Tub85D-HEG or Mst87F-HEG donors that express I-SceI during or after meiosis. Next, the earlier-expressing vasa-HEG and bam-HEG donors show different homing propensities, with 63% of repaired target chromosomes containing I-SceI when the bam-HEG donor is used as opposed to 36% with vasa-HEG. We also observe differing levels of GFP loss, a measure of cutting activity, between lines. The β-Tub85D-HEG and Mst87F-HEG donors show very high levels of I-SceI–induced double-strand breaks (90 and 79% respectively); aly-HEG was lower (49%) and the early-acting vasa-HEG and bam-HEG even lower (38 and 10% respectively). We also examined whether the influence of 3′-UTR choice extended beyond merely raising the level of expression. Comparison of a HEG-1–based Act5C-P–driven construct with its HEG-2–based equivalent showed both to have very similar homing fractions (29% vs. 32%) even though they exhibited very different cutting rates (5.5% vs. 34%; Table 1), suggesting that it is valid to make comparisons between homing rates obtained from HEG-1– and HEG-2–based constructs.

High rates of homing are achievable in both sexes:

According to modeling simulations, the fraction of HR-h we observe with Hsp26-HEG (11%) is not sufficient to allow a HEG to reach high frequency and induce a significant genetic load in a population when the HEG induces a fully penetrant recessive sterility/lethality phenotype (Deredec et al. 2008). However, as we indicate above, Rong and Golic (2003) reported that repair was predominantly HR-h in their assay system when I-SceI is induced by heat shock at 0–2 days after egg laying. We were interested to determine whether similar high rates could be achieved in the context of our homing assay and utilized our Hsp70-HEG donor to test this. Employing a similar heat-shock regime, inducing Hsp70-HEG expression, homing was observed in 74% of repaired target chromosomes (Table 1). While we have demonstrated that HR-h can be the predominant mode of DNA repair when the HEG is expressed in appropriate cells, we have, as yet, not achieved high levels of cutting with the weak promoters that drive expression in these cells. The act5C-P stock, which is expected to express at high levels throughout the germline, was designed with the expectation that the lower proportion of homing events from less specifically targeted expression could be traded off against a much higher rate of overall HEG activity. This was indeed the case, with 53% of the targets cut in males (as opposed to 7% with bam-HEG) and homing occurring in 32% of those cases (Table 1). Homed targets constituted 20% of total targets with act5C-P-HEG, as opposed to 4% with bam-HEG. More importantly, we observe homing for the first time in female trans-heterozygotes with 35% of targets cut and homing observed with a very creditable 50% of repair events. Our other lines do not show significant HEG activity in female trans-heterozygotes.

Homing can occur from an ectopic site:

In a field situation, to target an endogenous gene with an engineered HEG, the donor line needs to have the HEG cassette inserted into that target. While in principle such a donor might be generated by a targeted homologous recombination system, we wished to ascertain whether we could generate such a chromosome by homing ectopically. We therefore tested whether a HEG-induced DSB could be homed by a HEG donor located on another chromosome and assayed for such ectopic repair events by measuring the rate at which a pDarkLime target on chromosome 2 could be repaired from vasa-HEG donor on chromosome 3. We examined 1057 target chromosomes and identified 302 cases (29%) in which I-SceI activity had abolished GFP fluorescence: 5 of these showed ectopic homing as evidenced by RFP fluorescence. When repeated with the more actively homing Act5C-P-HEG, we found 181 GFP negatives from screening 327 target chromosomes (55%), 5 of which were presumptive homing events judged by RFP fluorescence. We verified that the HEG insert had homed into the target site by PCR across the insert/target junction (product Y in Figure 4B). We were concerned that errors in scoring could have led to the presence of the donor transgene in the ectopic samples, yielding a false positive in the PCR test. We used an EcoRI site that is present only in the target construct to assay this: PCR amplification and EcoRI digestion of DNA from the ectopically homed chromosomes excluded contamination. We also characterized some of the ectopic events more thoroughly by PCR across both insert/target junctions and these yielded the expected results, further confirming that the ectopic events are genuine.

While the ectopic homing rate is lower than the frequency of homing we observe when donors and targets are at homologous positions (Table 1), it nevertheless demonstrates that ectopic homing can occur. Of course, once an ectopic homing event is recovered in a particular target, it provides a homologous donor for subsequent homing. This may be particularly important in cases where gene targeting of the vector species is difficult.

DISCUSSION

The HEG gene drive strategy requires high rates of HR-h in the germline. However, with previously reported rates ranging from <19% to >65% for HR-h in the male germline, an assessment of the feasibility of this strategy required a more extensive examination of DNA repair in the Drosophila germline. To this end, we developed a panel of transgenic Drosophila lines that express I-SceI at specific stages of spermatogenesis. We also developed a DNA repair assay tailored to measuring HR-h rates that, when applied to our lines, allowed us to refine and reevaluate previous findings on the spectrum of DNA repair in the testis. Understanding the available repair pathways directly impacts our ability to engineer HEG expression to harness homologous repair rather than repair pathways that do not facilitate HEG copying.

We found HR-h rates vary widely depending on where I-SceI is expressed. This is consistent with an earlier study where I-SceI was driven by ubiquitin and β-Tub85D promoters (Preston et al. 2006b). They found that single-strand annealing (SSA), with a small contribution from HR-h, comprised most repair events observed with a widely expressed ubiquitin promoter (Ubi-p63E), whereas NHEJ dominated at later stages of spermatogenesis as evidenced by the results with the β-Tub85D promoter. Our results, generated with a broader panel of I-SceI–expressing lines, show that repair pathway preference is more extreme than previously envisaged. While very high levels of HR-h are observed in spermatogonia (bam-HEG), they are almost completely replaced by NHEJ in early primary spermatocytes (aly-HEG) and at subsequent stages (β-Tub85D-HEG and Mst87F-HEG). The inaccessibility of the homolog postmeiosis could explain the predominance of NHEJ seen with Mst87F-HEG but not with the aly or β-Tub85D lines, which express I-SceI in tetraploid spermatocytes where the homolog is available. Meiosis in male Drosophila is achiasmate, so perhaps the homologous recombination repair pathway is repressed as a result (Preston et al. 2006b).

We also observed high levels of HR-h in female trans-heterozygotes, a finding consistent with previous observations made during targeted mutagenesis by homologous recombination. Rong and coworkers observed that the ratio of HR events to illegitimate events was sixfold better in females than in males (Rong and Golic 2000). Indeed, since Act5C-P-HEG transmits maternal HEG transcripts to progeny that do not have a donor template available, HEG activity in these progeny can resolve only as extraneous NHEJ events in our assay (Simmons et al. 2002). Since we cannot distinguish between NHEJ events arising in the oocyte and those arising through maternally derived HEG activity in the progeny, the rate of cutting in the oocyte is almost certainly overstated and the true rate of homing within the oocyte is higher than the 50% we report in Table 1.

The high levels of HR-h observed in both sexes suggest that the homing efficiency necessary for the HEG gene drive strategy is achievable when the HEG is expressed at an appropriate stage of germline differentiation. Given that homing efficiency varies so widely during spermatogenesis, the identification of both the homing-competent cell type in the germline of the target species and promoters that can accurately target that tissue at high efficiency will be vital to the successful deployment of the HEG gene drive strategy. We recognize that the levels of HEG activity we observe in spermatogonia are lower than desired and that the design of customized HEGs remains a nontrivial task (Chevalier et al. 2002; Ashworth et al. 2006). We are, however, confident that these issues can be addressed with further technical development. Although our work is centered on a tractable model dipteran, we believe that there will be sufficient shared evolutionary similarities to the malarial disease vector, Anopheles gambiae, to be optimistic that this strategy can also be made to work in a dipteran that has a considerable impact on global health. In addition, while our work was primarily directed at the HEG gene drive strategy, our findings are also relevant for optimizing HR-based techniques for in vivo site-directed mutagenesis in Drosophila, which also relies on achieving efficient HR-h (Rong and Golic 2000).

During our study, we made findings that, although not directly pertinent to the HEG gene drive strategy, extend and clarify our current understanding of Drosophila germline DNA repair. We resolved an apparent discrepancy with regard to the rates of HR-h achievable in the male germline (Rong and Golic 2003; Preston et al. 2006b). The high levels of HR-h observed by Rong and Golic result from induction of I-SceI expression in larval testis, a stage that almost entirely comprises spermatogonia, the cell type that supports the highest rate of HR-h in our experiments. The model that emerges from our work, where HR-h is restricted to one cell type only, may require revisiting some previous findings. Preston and co-workers reported HR-h rates rising with age using Ubi-p63E–regulated I-SceI and interpreted this as evidence of an age-dependent change in preferred repair pathway (Preston et al. 2006a). However, it could also arise from an increase in the proportion of events repaired in the spematogonia (SG) rather than the later NHEJ-favoring cell types, for example, as a consequence of lengthened cell cycle times (Wallenfang et al. 2006; Boyle et al. 2007). We are currently attempting to distinguish between these possibilities.

In addition, while some of the promoters we and others have used are expected to direct expression of I-SceI in the male GSCs, none of the experiments to date appear to be informative with regard to DNA repair in the GSCs. Expression of I-SceI in the male GSCs should lead to the eventual removal of I-SceI target sites as these are cut and processed irreversibly to fixation by HR-h, NHEJ, and SSA. While the use of a ubiquitin promoter is expected to drive expression in the GSCs, the rise in HR-h frequency with age suggests that the observed repair events could have arisen only after the GSC stage rather than in the GSCs themselves (Preston et al. 2006a). Our vasa-HEG stock, which should also express I-SceI in the GSCs, did not show the expected rise in fraction of targets cut with age that should accompany GSC expression (data not shown). The choice of repair pathway used in the GSCs therefore remains an open question.

Finally, we became aware of a further difficulty in interpreting DSB repair experiments in the Drosophila testis. When I-SceI is expressed during late stages of spermatogenesis (aly-HEG, β-Tub85D-HEG, Mst87F-HEG), we occasionally observed progeny where the GFP phenotype is mosaic, apparent when one eye is GFP positive and the other is GFP negative. We excluded I-SceI carryover in sperm as a contributory factor (data not shown) and suggest that mosaics arise from unrepaired DSBs being packaged into spermatozoa and subsequently repaired in the zygote. Previous reports from irradiation experiments suggest the loss of DNA repair in the testis after ∼2–4 days of pupal life, corresponding to the spermatid stages (Kaufmann 1940; Sobels 1974). Our results suggest that repair may also be incomplete during the spermatocyte stage. The low level of mosaicism we observe suggests that most DSBs are repaired either within the testis or prior to the first S phase in the zygote. Preston and co-workers report an intriguing set of experiments where I-SceI expression late in spermatogenesis yields mainly NHEJ events while SSA dominated when I-SceI was maternally supplied to the zygote. This was interpreted as evidence for the differential use of repair pathways through development (Preston et al. 2006b). If we assume that the bulk of DSBs arising from late-expressed I-SceI are inherited unrepaired by the zygote and that maternally inherited I-SceI transcripts or protein result in cleavage of the paternally derived target postreplicatively, the contrast between the results of Preston et al.’s experiments could be interpreted as NHEJ being used to salvage damaged sperm chromosomes, while DSBs arising slightly later in the early zygote may be handled by SSA instead, again suggesting a rapid shift in the preferred repair pathway. When taken together with our findings with respect to HR-h in spermatogonia, the suggestion that drastic changes in repair pathway choice are a common feature in D. melanogaster seems plausible.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Rong for plasmids, Michael Ashburner and Austin Burt for comments, and the editor and reviewers for constructive suggestions for the improvement of the manuscript. This work was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation via a Grand Challenges in Global Health grant to Austin Burt (Imperial College).

Acknowledgments

Note added in proof: A demonstration that HEG-based gene drive can occur in Anopheles gambiae is reported in Windbichler N., M. Menichelli, P. A. Papathanos, S. B. Thyme, H. Li, et al., 2011. A synthetic homing endonuclease-based gene drive system in the human malaria mosquito. Nature (in press).

LITERATURE CITED

- Ashworth J., Havranek J., Duarte C., Sussman D., Monnat R., et al. , 2006. Computational redesign of endonuclease DNA binding and cleavage specificity. Nature 441: 656–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreau C., Benson E., Gudmannsdottir E., Newton F., White-Cooper H., 2008. Post-meiotic transcription in Drosophila testes. Development 135: 1897–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond-Matthews B., Davidson N., 1988. Transcription from each of the Drosophila Act5C leader exons is driven by a separate functional promoter. Gene 62: 289–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle M., Wong C., Rocha M., Jones D., 2007. Decline in self-renewal factors contributes to aging of the stem cell niche in the Drosophila testis. Cell Stem Cell 1: 470–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt A., 2003. Site-specific selfish genes as tools for the control and genetic engineering of natural populations. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270: 921–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt A., Trivers R., 2005. Genes in Conflict: The Biology of Selfish Genetic Elements. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R., Tour O., Palmer A., Steinbach P., Baird G., et al. , 2002. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 7877–7882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D., Mckearin D., 2003. A discrete transcriptional silencer in the bam gene determines asymmetric division of the Drosophila germline stem cell. Development 130: 1159–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier B., Kortemme T., Chadsey M., Baker D., Monnat R., et al. , 2002. Design, activity, and structure of a highly specific artificial endonuclease. Mol. Cell 10: 895–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deredec A., Burt A., Godfray H., 2008. The population genetics of using homing endonuclease genes (HEGs) in vector and pest management. Genetics 179: 2013–2026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R., Lis J., 1990. Multiple, compensatory regulatory elements specify spermatocyte-specific expression of the Drosophila melanogaster hsp26 gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10: 131–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R., Wolfner M., Lis J., 1986. Spacial and temporal pattern of hsp26 expression during development. EMBO J. 5: 747–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonczy P., Matunis E., Dinardo S., 1997. bag-of-marbles and benign-gonial-cell-neoplasm act in the germline to restrict proliferation during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Development 124: 4361–4371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth A., Fish M., Nusse R., Calos M., 2004. Construction of transgenic Drosophila by using the site-specific integrase from phage φC31. Genetics 166: 1775–1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay B., Jan L., Jan Y., 1988. A protein component of Drosophila polar granules is encoded by vasa and has extensive sequence similarity to ATP-dependent helicases. Cell 55: 577–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn C., Wimmer E., 2000. A versatile vector set for animal transgenesis. Dev. Genes Evol. 210: 630–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Schlitz D., Engels W., 2006. The effect of gap length on double-strand break repair in Drosophila. Genetics 173: 2033–2038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann B. P., 1940. The time interval between X-radiation of sperm and chromosome recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 27: 18–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiger A., White-Cooper H., Fuller M., 2000. Somatic support cells restrict germline stem cell self-renewal and promote differentiation. Nature 407: 750–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R., Schafer U., Schafer M., 1988. Cis-acting regions sufficient for spermatocyte-specific transcriptional and spermatid-specific translational control of the Drosophila melanogaster gene mst(3)gl-9. EMBO J. 7: 447–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laski F. A., Rubin G. M., 1989. Analysis of the cis-acting requirements for germ-line-specific splicing of the P-element ORF2–ORF3 intron. Genes Dev. 3: 720–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laski F., Rio D., Rubin G., 1986. Tissue specificity of Drosophila P element transposition is regulated at the level of mRNA splicing. Cell 44: 7–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michiels F., Gasch A., Kaltschmidt B., Renkawitz-Pohl R., 1989. A 14 bp promoter element directs the testis specificity of the Drosophila beta-2 tubulin gene. EMBO J. 8: 1559–1565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris C., Benson E., White-Cooper H., 2009. Determination of gene expression patterns using in situ hybridization to Drosophila testes. Nat. Protoc. 4: 1807–1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston C., Flores C., Engels W., 2006a. Age-dependent usage of double-strand break repair pathways. Curr. Biol. 16: 2009–2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston C., Flores C., Engels W., 2006b. Differential usage of alternative pathways of double-strand break repair in Drosophila. Genetics 172: 1055–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team, 2010. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. http://www.R-project.org

- Rong Y. S., Golic K. G., 2000. Gene targeting by homologous recombination in Drosophila. Science 288: 2013–2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong Y., Golic K., 2003. The homologous chromosome is an effective template for repair of mitotic DNA double-strand breaks in Drosophila. Genetics 165: 1831–1842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouet P., Shih F., Jasin M., 1994. Expression of a site-specific endonuclease stimulates homologous recombination in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 6064–6068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano H., Nakamura A., Kobayashi S., 2002. Identification of a transcriptional regulatory region for germline-specific expression of vasa gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Mech. Dev. 112: 129–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons M. J., Haley K. J., Thompson S. J., 2002. Maternal transmission of P element transposase activity in Drosophila melanogaster depends on the last intron. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 9306–9309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkins F. P., Gould F., 2006. Gene drive systems for insect disease vectors. Nat. Genet. 7: 427–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobels F. H., 1974. The persistence of chromosome breaks in different stages of spermatogenesis of Drosophila. Mutat. Res. 23: 361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulina N., Matunis E., 2001. Control of stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila spermatogenesis by JAK-STAT signaling. Science 294: 2546–2549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vibranovski M. D., Chalopin D. S., Lopes H. F., Long M., Karr T. L., 2010. Direct evidence for postmeiotic transcription during Drosophila melanogaster spermatogenesis. Genetics 186: 431–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallenfang M., Nayak R., Dinardo S., 2006. Dynamics of the male germline stem cell population during aging of Drosophila. Aging Cell 5: 297–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Mann R., 2003. Requirement for two nearly identical TGIF-related homeobox genes in Drosophila spermatogenesis. Development 130: 2853–2865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White-Cooper H., Leroy D., Mcqueen A., Fuller M., 2000. Transcription of meiotic cell cycle and terminal differentiation genes depends on a conserved chromatin associated protein, whose nuclear localisation is regulated. Development 127: 5463–5473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]